Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Examine racial/ethnic differences in smoking susceptibility among US youth nonsmokers over time and age.

METHODS:

We used nationally representative samples of youths who never tried cigarettes (N = 143 917; age, 9–21, mean, 14.01 years) from National Youth Tobacco Survey, 1999 to 2014. We used time-varying effect modeling to examine nonlinear trends in smoking susceptibility adjusted for demographics, living with smokers, and exposure to tobacco advertising.

RESULTS:

Compared with non-Hispanic whites (NHWs), Hispanics were more susceptible to smoking from 1999 to 2014 (highest adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.67 in 2012). Non-Hispanic blacks were less susceptible to smoking than NHWs from 2000 to 2009 (lowest aOR, 0.80 in 2003–2005). Non-Hispanic Asian Americans were less susceptible to smoking from 2000 to 2009 (aOR, 0.83), after which they did not differ from NHWs. Other non-Hispanics were more susceptible to smoking than NHWs from 2012 to 2014 (highest aOR, 1.40 in 2014). Compared with NHWs, non-Hispanic blacks and other non-Hispanics were more susceptible to smoking at ages 11 to 13 (highest aOR, 1.22 at age 11.5 ) and 12 to 14 (highest aOR, 1.27 at age 12 ), respectively. Hispanics were more susceptible to smoking throughout adolescence peaking at age 12 (aOR, 1.60) and age 16.5 (aOR, 1.46). Non-Hispanic Asian Americans were less susceptible to smoking at ages 11 to 15 (lowest aOR, 0.76 at ages 11–13 ).

CONCLUSIONS:

Racial/ethnic disparities in smoking susceptibility persisted over time among US youth nonsmokers, especially at ages 11 to 13 . Interventions to combat smoking susceptibility are needed.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Smoking susceptibility is a predictor of smoking behavior. Smoking prevalence and age of onset among youth vary by race and ethnicity. Less is known about racial and ethnic disparities in youth smoking susceptibility and if these disparities change over age.

What This Study Adds:

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics and other non-Hispanics were more/equally susceptible to smoking. Non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic Asian Americans were less/equally susceptible from 1999 to 2014. All except non-Hispanic Asian Americans exhibited heightened susceptibility at ages 11 to 13 years.

Youth is a critical developmental stage for cigarette smoking prevention efforts. Roughly 5.6 million or 1 in every 13 individuals who are ≤17 years will prematurely die of smoking.1 A majority of daily smokers (88%) initiates smoking by age 18.2 Youth are sensitive to low levels of nicotine exposure and, thus, are more at risk for nicotine dependence and addiction compared with adults3,4 and heavy and long-duration use of cigarettes into adulthood.2,3,5 Finally, early smoking initiation is associated with use of other illicit drugs and detrimental and persistent health and social outcomes throughout the lifetime.2,3

Smoking prevalence, age of onset, intensity of use, and rate and speed of smoking progression among youth varies by race and ethnicity. In 2014, among middle-school students, Hispanics had the highest prevalence at 3.7% followed by non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) at 2.2% and non-Hispanic blacks (NHBs) at 1.7%.6 Among high-school students, NHWs had the highest smoking prevalence at 10.8% followed by Hispanics at 8.8%, other non-Hispanics (ONHs) at 5.3%, and NHBs at 4.5%.6 Compared with their white counterparts, African Americans initiate smoking later, consume fewer cigarettes per day, and progress more slowly toward regular smoking.7 Rate of smoking initiation and progression from nondaily to daily smoking is higher among white (18.2% and 18.8%) and Hispanic (20.3% and 15.9%) youth than black youth (16.2% and 9.6%).8 African Americans have lower smoking prevalence in adolescence but higher smoking prevalence in adulthood when compared with whites.9 Among those who initiate smoking by age 14 years, continued smoking into adulthood is higher among African Americans compared with their white counterparts.9

Little is known about smoking susceptibility, which precedes smoking behavior. Defined as lack of a firm commitment to not smoke, smoking susceptibility is a predictor of smoking experimentation among youth.10 Unger and colleagues11 found that susceptible seventh grade adolescents were 3 times more likely to try cigarettes in eighth grade and 2 times more likely to try cigarettes in ninth grade compared with their nonsusceptible counterparts. Another study found that smoking susceptibility predicted smoking status independent of stages of smoking (eg, precontemplation).12 However, less is known about racial and ethnic disparities in youth smoking susceptibility. To date, 1 study has assessed disparities in smoking susceptibility among youth nonsmokers and found that Hispanics were almost 2 times more likely to be susceptible to smoking compared with NHWs.13 In addition, although age is associated with a gradual increase in smoking prevalence and intensity of use,14 no study to date has examined whether racial and ethnic disparities in smoking susceptibility change over age. Thus, smoking susceptibility can be an early indicator of shifts in racial and ethnic composition of smokers over time. Additionally, smoking susceptibility can be an indicator of ages at which youths are most at risk for smoking and, thus, illuminates the pivotal age for smoking prevention interventions.

The current study aimed to answer 2 research questions: (1) how did youth smoking susceptibility differ by race and ethnicity from 1999 to 2014; and (2) how did smoking susceptibility vary by age? We extend previous research on youth smoking in several ways. First, by examining smoking susceptibility, we extend literature on smoking prevalence to smoking antecedents. Second, by examining susceptibility by age, we extend research that has been limited to age of onset and stages of smoking among youth.9,15 Third, by examining disparities in smoking susceptibility over time and age for 5 racial and ethnic groups, we extend existing literature that has been limited to comparing 2 racial/ethnic groups, primarily NHBs to NHWs.7

Methods

We analyzed data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) from 1999 to 2014. NYTS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional, self-administered survey of US middle- and high-school students. NYTS was initiated in 1999 to gauge youths’ beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors around tobacco use. We used all 10 NYTS datasets available from 1999 to 2014. NYTS uses a multistage sampling design. Overall response rate ranged from 68.4% in 2013 to 84.8% in 2009. A description of NYTS sampling procedures is available online.16

We limited our analyses to never smokers (ie, never tried cigarettes, even 1 or 2 puffs) who answered at least 1 of 3 susceptibility questions (N =143 917; 51.7% female; 42.9% high-school students; 50.8% NHW, 17.2% NHB, 24.3% Hispanic, 5.5% non-Hispanic Asian Americans [NHA], and 2.0% ONH). ONH included American Indians, Alaska natives, native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.17 Sample sizes ranged from 7782 in 1999 to 17 847 in 2012.

Measures

Susceptibility to smoking was assessed using 3 questions: (1) “Do you think you will try a cigarette soon?” (2) “Do you think you will smoke a cigarette in the next year?” (3) “If one of your friends were to offer you a cigarette, would you smoke it?” From 1999 to 2011, responses for the first question were yes and no. From 2012 to 2014, responses for the first question were definitely yes, probably yes, probably not, and definitely not. To harmonize differences in response choices across years, we recoded definitely yes and probably yes into 1 = yes, and probably not and definitely not into 0 = no for years 2012 to 2014. Responses for the second and third questions were consistent across years and were recoded as 1 = yes for definitely yes, probably yes, and probably not and 0 = no for definitely not.10 We classified participants who responded “no” to all 3 susceptibility questions as 0 = nonsusceptible to smoking and those who responded “yes” to at least 1 of the 3 questions as 1 = susceptible.

Data on gender (0 = female, 1 = male), grade (0 = middle school, 1 = high school), and living with a smoker (0 = no, 1 = yes) were collected. Exposure to tobacco advertising on the internet (“When you are using the internet, how often do you see ads for tobacco products?”) and in-store (“When you go to a convenience store, supermarket, or gas station, how often do you see ads for cigarettes and other tobacco products or items that have tobacco company names or pictures on them?”) were recoded into 0 = no for response choices “I don’t use the internet/I never go to a convenience store, supermarket, or gas station” and “never,” and 1 = yes for responses “hardly ever,” “most of the time,” and “some of the time”.

Data Analysis

We used time-varying effect modeling (TVEM) to examine variation in smoking susceptibility by race and ethnicity over time (1999–2014) and age (11–18 years old). In examining smoking susceptibility over age, we limited our analyses to 11 to 18 year-olds because of low frequencies for ages 9 to 10 and 19 to 21 years. We used %TVEM SAS Marco Suite, version 3.1.0. (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

TVEM is a new statistical tool that estimates regression coefficients as a nonparametric function of a time metric. TVEM produces infinite coefficients and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) plotted in irregular curves. In the Results, we describe the shape of TVEM curves and report highs or lows in the model-estimated prevalence of smoking susceptibility. We supplemented TVEM figures with tables of crude weighted estimates of smoking susceptibility. We used SAS (version 9.3) to conduct weighted descriptive statistics.

We ran intercept models averaged across all 5 racial/ethnic groups and then separately for each group to allow race and ethnicity to moderate the effect of time/age on smoking susceptibility.

|

where sus is smoking susceptibility and is the log-odds of smoking susceptibility at a given time (t). Then, we included race/ethnicity to examine the log odds of smoking susceptibility (slope function) for each racial/ethnic group compared with NHWs as a reference group (coded 0). In these models, we included 5 time-varying covariates: gender, school, living with a cigarette user, and exposure to tobacco advertising on the internet and in stores. We added the survey year as a time-varying covariate when examining smoking susceptibility over age. This allowed the associations between covariates and smoking susceptibility to vary over time.

|

Results

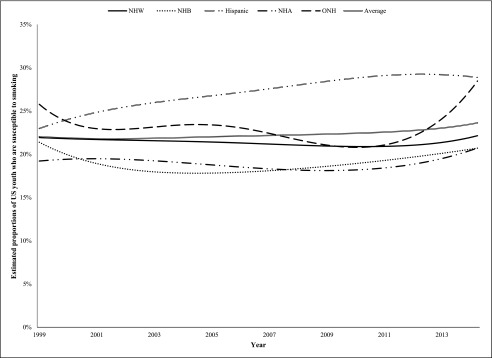

Sample characteristics appear in Table 1 and Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Overall estimated proportions of smoking susceptibility for all racial/ethnic groups remained at 21% from 1999 to 2007, after which proportions of susceptible nonsmokers increased to 23% in 2014 (Fig 1). Estimated proportions of NHW never smokers who were susceptible to smoking remained steady at 21% from 1999 to 2014. Susceptible NHB never smokers dropped from 21% in 1999 to 17% in 2003 to 2006, after which susceptibility increased to 20% in 2014. Susceptibility among Hispanic never smokers has been steadily increasing from 22% in 1999 to 28% in 2014. Estimated proportions of susceptible NHA never smokers were at 18% from 1999 to 2010, after which susceptibility increased to 20% in 2014. The lowest proportion of ONHs who were susceptible to smoking was in 2010 at 20%, whereas the highest was in 2014 at 28%.

TABLE 1.

Weighted Sample Characteristics, 1999–2014

| Year | 1999 (n = 7782) | 2000 (n = 16 772) | 2002 (n = 13 505) | 2004 (n = 15 641) | 2006 (n = 15 795) | 2009 (n = 14 066) | 2011 (n = 12 699) | 2012 (n = 17 847) | 2013 (n = 13 160) | 2014 (n = 16 650) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Girl | 51.3 (49.6–52.9) | 52.0 (50.8–53.2) | 51.9 (50.2–53.5) | 51.8 (50.4–53.2) | 52.2 (50.9–53.5) | 50.4 (48.9–51.9) | 50.6 (49.3–51.9) | 50.5 (49.6–51.5) | 50.0 (48.4–51.5) | 50.7 (48.6–52.7) |

| Boy | 48.6 (47.0–50.3) | 47.9 (46.7–49.1) | 48.0 (46.4–49.7) | 48.1 (46.7–49.5) | 47.7 (46.4–49.0) | 49.5 (48.0–51.0) | 49.3 (48.0–50.6) | 49.4 (48.4–50.3) | 49.9 (48.4–51.5) | 49.2 (47.2–51.3) |

| Agea | 13.18 (13.14–13.22) | 13.91 (13.88–13.94) | 14.00 (13.97–14.03) | 13.86 (13.83–13.89) | 14.03 (14.00–14.06) | 14.09 (14.06–14.13) | 14.13 (14.09–14.16) | 14.14 (14.11–14.17) | 14.25 (14.22–14.29) | 14.18 (14.15–14.22) |

| Race | ||||||||||

| NHW | 61.6 (55.1–68.1) | 68.2 (62.9–73.5) | 67.0 (62.3–71.8) | 68.7 (63.3–74.1) | 67.1 (61.9–72.4) | 62.1 (54.3–69.9) | 62.1 (55.8–68.5) | 60.1 (55.2–64.9) | 58.3 (51.5–65.1) | 58.5 (52.5–64.4) |

| NHB | 18.6 (12.8–24.3) | 14.3 (11.1–17.4) | 13.5 (10.6–16.4) | 14.6 (10.7–18.5) | 14.7 (10.9–18.6) | 15.0 (10.4–19.7) | 14.4 (10.3–18.5) | 14.3 (10.6–18.0) | 15.9 (10.5–21.3) | 15.5 (11.6–19.4) |

| Hispanics | 14.6 (11.7–17.4) | 12.0 (8.5–15.4) | 13.6 (10.6–16.6) | 11.7 (9.1–14.4) | 13.2 (10.4–16.1) | 17.3 (12.6–22.0) | 18.3 (13.9–22.6) | 20.2 (16.7–23.7) | 20.0 (15.6–24.3) | 20.9 (17.4–24.5) |

| NHA | 3.6 (2.4–4.8) | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) | 3.6 (2.8–4.4) | 3.8 (2.7–5.0) | 3.7 (2.6–4.8) | 4.4 (3.1–5.7) | 3.9 (2.7–5.0) | 4.4 (2.8–6.0) | 4.5 (2.8–6.2) | 4.0 (2.6–5.3) |

| ONH | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 2.0 (1.6–2.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.1) | 1.1 (0.5–1.6) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.1) |

| School | ||||||||||

| Middle school | 62.4 (55.4–69.4) | 60.0 (55.8–64.1) | 57.5 (51.8–63.1) | 56.1 (50.8–61.5) | 55.4 (50.1–60.7) | 52.4 (44.6–60.2) | 51.3 (45.1–57.4) | 51.2 (46.5–55.9) | 50.9 (46.4–55.3) | 49.9 (43.5–56.2) |

| High school | 37.5 (30.5–44.5) | 39.9 (35.8–44.1) | 42.4 (36.8–48.1) | 43.8 (38.4–49.1) | 44.5 (39.2–49.8) | 47.5 (39.7–55.3) | 48.6 (42.5–54.8) | 48.7 (44.0–53.4) | 49.0 (44.6–53.5) | 50.0 (43.7–56.4) |

| Living with a smoker | ||||||||||

| No | 68.9 (67.0–70.9) | 69.6 (68.0–71.2) | 67.9 (66.1–69.7) | 68.9 (66.9–70.9) | 69.6 (67.6–71.7) | 72.7 (70.5–74.9) | 74.3 (71.7–76.9) | 72.4 (70.6–74.2) | 76.0 (74.1–77.9) | 75.9 (74.5–77.4) |

| Yes | 31.0 (29.0–32.9) | 30.3 (28.7–31.9) | 32.0 (30.2–33.8) | 31.0 (29.0–33.0) | 30.3 (28.2–32.3) | 27.2 (25.0–29.4) | 25.6 (23.0–28.2) | 27.5 (25.7–29.3) | 23.9 (22.0–25.8) | 24.0 (22.5–25.4) |

| Exposure to internet ads | ||||||||||

| No | 57.8 (55.1–60.6) | 43.7 (41.9–45.5) | 32.4 (30.9–34.0) | 34.2 (32.5–35.9) | 32.1 (30.6–33.6) | 28.7 (26.8–30.5) | 25.2 (23.7–26.6) | 22.3 (21.3–23.3) | 21.0 (19.8–22.2) | 17.6 (16.7–18.6) |

| Yes | 42.1 (39.3–44.8) | 56.2 (54.4–58.0) | 67.5 (65.9–69.0) | 65.7 (64.0–67.4) | 67.8 (66.3–69.3) | 71.2 (69.4–73.1) | 74.7 (73.3–76.2) | 77.6 (76.6–78.6) | 78.9 (77.7–80.1) | 82.3 (81.3–83.2) |

| Exposure to in-store ads | ||||||||||

| No | 9.0 (7.5–10.6) | 5.5 (4.8–6.3) | 5.3 (4.6–6.0) | 9.1 (8.0–10.2) | 9.2 (8.1–10.2) | 10.3 (8.7–11.9) | 8.9 (8.0–9.9) | 12.6 (11.6–13.6) | 12.4 (11.1–13.6) | 8.3 (7.5–9.1) |

| Yes | 90.9 (89.3–92.4) | 94.4 (93.6–95.1) | 94.6 (93.9–95.3) | 90.8 (89.7–91.9) | 90.7 (89.7–91.8) | 89.6 (88.0–91.2) | 91.0 (90.0–91.9) | 87.3 (86.3–88.3) | 87.5 (86.3–88.8) | 91.6 (90.8–92.4) |

| Susceptibility to smoking | ||||||||||

| No | 78.3 (76.8–79.8) | 77.7 (76.7–78.8) | 79.3 (78.0–80.6) | 77.7 (76.8–78.7) | 79.1 (77.9–80.3) | 79.5 (78.0–81.0) | 77.0 (75.6–78.5) | 74.9 (74.0–75.9) | 82.2 (81.0–83.3) | 75.2 (74.1–76.4) |

| Yes | 21.6 (20.1–23.1) | 22.2 (21.1–23.2) | 20.6 (19.3–21.9) | 22.2 (21.2–23.1) | 20.8 (19.6–22.0) | 20.4 (19.0–21.9) | 22.9 (21.4–24.3) | 25.0 (24.0–25.9) | 17.7 (16.6–18.9) | 24.7 (23.5–25.8) |

Data presented are from all available NYTS datasets between 1999 and 2014. n, unweighted N.

Cells represent mean and 95% CIs.

FIGURE 1.

Proportions of US youth nonsmokers who are susceptible to smoking by race and ethnicity, 1999 to 2014. “Average” refers to estimated proportions of never smokers who were susceptible to smoking in all 5 racial/ethnic groups. Data presented are from all available NYTS datasets between 1999 and 2014.

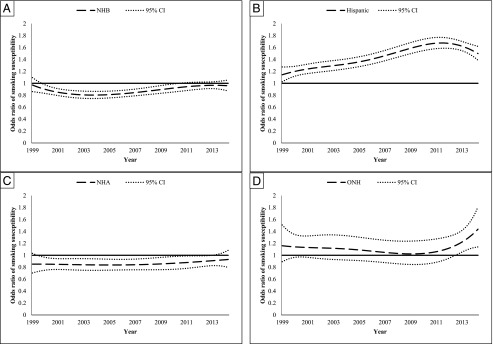

Figure 2A shows that from 2000 to 2009, NHBs were less susceptible to smoking compared with NHWs (lowest adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.80 in 2003–2005). Starting in 2010, NHWs and NHBs did not differ in their susceptibility to smoking. Similarly, NHAs were less susceptible to smoking from 2000 to 2009 (lowest aOR, 0.83), after which they did not differ from NHWs (Fig 2C). Conversely, Hispanics were more susceptible to smoking compared with NHWs from 1999 (aOR, 1.16) to 2014 (aOR, 1.49), peaking in 2012 (aOR, 1.67) (Fig 2B). Finally, ONHs did not differ from NHWs in smoking susceptibility from 1999 to 2012, after which they became more susceptible to smoking (aOR, 1.40 in 2014) (Fig 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Odds ratio of susceptibility among racial/ethnic youth compared with NHWs, 1999 to 2014. A, Odds ratio of susceptibility among NHBS compared with NHWs. B, Odds ration of susceptibility among Hispanics compared with NHWs. C, Odds ratio of susceptibility among NHAs compared with NHWs. D, Odds ratio of susceptibility among OHNs compared with NHWs. Time-varying covariates: gender (0 = female, 1 = male), grade (0 = middle school, 1 = high school), living with a cigarette user (0 = no, 1 = yes), exposure to internet tobacco advertising (0 = no, 1 = yes), and exposure to in-store tobacco advertising (0 = no, 1 = yes). Data presented are from all available NYTS datasets between 1999 and 2014

Youths were most susceptible to smoking around 13 to 15 years of age with 27% of nonsmokers being susceptible to smoking at age 14 years (Fig 3). Figure 4A shows that, compared with NHWs, NHBs were more susceptible to smoking from age 11 to 13 years, peaking around age 11.5 years (aOR, 1.22). Starting at age 13.5 years, NHBs were consistently less susceptible to smoking, with the lowest susceptibility at age 18 years (aOR, 0.66). Similarly, ONHs were more susceptible to smoking from age 12 to 14 years, peaking around age 12 years (aOR, 1.27). At ages 17 and 18 years, ONHs were equally susceptible to smoking as their NHW counterparts (Fig 4D). Hispanics were consistently more susceptible to smoking throughout the adolescent years, peaking at ages 12 (aOR, 1.60) and 16.5 years (aOR 1.40) (Fig 4B). Conversely, NHAs were less susceptible to smoking in early adolescence (ie, ages 11 to 15 years [lowest aOR, 0.76 at ages 11–13 years]), after which they no longer differed from NHWs in smoking susceptibility (Fig 4C).

FIGURE 3.

Proportions of US youth nonsmokers who are susceptible to smoking by age. “Average” refers to estimated proportions of never smokers who were susceptible to smoking in all 5 racial/ethnic groups.

FIGURE 4.

Odds ratio of susceptibility among racial/ethnic youth compared with NHWs by age. A, Odds ratio of susceptibility among NHBs compared with NHWs. B, Odds ratio of susceptibility among Hispanics compared with NHWs. C, Odds ratio of susceptibility among NHAs compared with NHWs. D, Odds ratio of susceptibility among OHNs compared with NHWs. Time-varying covariates: gender (0 = female, 1 = male), year (continuous), living with a cigarette user (0 = no, 1 = yes), exposure to internet tobacco advertising (0 = no, 1 = yes), and exposure to in-store tobacco advertising (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Discussion

This study is the first to document trends in racial and ethnic disparities in cigarette smoking susceptibility from 1999 to 2014, and the extent to which these disparities develop over age. Interestingly, although smoking prevalence has been declining among youth,2 smoking susceptibility has either remained nearly steady (eg, NHWs) or increased (eg, Hispanics) among never smokers. One explanation could be that tobacco control policies (eg, youth tobacco sale and marketing restrictions, federal and state cigarette tax increases, clean indoor air policies) have hindered smoking initiation.18 However, these policies do not seem to be effective in reducing smoking susceptibility. Susceptible never smokers represent a reservoir of youth who can experiment and/or use noncigarette tobacco products (eg, e-cigarettes), which have been on the rise among youth.19

Our results on trends in smoking susceptibility show disparities by race and ethnicity over time that somewhat coincide with smoking disparities. We found that, compared with NHWs, NHBs and NHAs were less susceptible to smoking, but have become equally susceptible to smoking starting in 2010. Lanza and colleagues20 found that any reported cigarette use among high school students was higher among NHWs (41% in 1990s to 20% in 2013) than NHBs (10% from 1992 to 2013). The NYTS shows that current cigarette use, measured as number of days of cigarette use during the past 30 days, was consistently higher among NHW (16.0% to 5.4%) compared with NHB (8.0% to 2.7%) high school students from 2000 to 2012.21 Data from 2006–2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health show current smoking among 12 to 17 year olds at 4.1% for NHAs (vs 11.8% for NHWs and 5.9% for NHBs).22

Compared with NHWs, Hispanics have been consistently more susceptible to smoking, whereas ONHs have become more susceptible to smoking starting in 2013. Conversely, prevalence data show opposite patterns where prevalence is lower among Hispanics but higher among ONHs compared with NHWs. For example, NYTS data show that current cigarette use among Hispanic high school students was at 9.8% in 2000 and 4.1% in 2012, lower than NHWs at 16.0% and 5.4%, respectively.21 The 2014 NYTS data show that past 30 day cigarette use was at 8.8% for Hispanic high school students (vs 10.8% for NHWs) but at 3.7% for middle school students (vs 2.2% for NHWs).6 In addition, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health shows that prevalence of cigarette use among ONHs was at 17.2% (vs 11.8% for NHWs).22

Smoking susceptibility is an established predictor of smoking behavior at the individual level.10,11 However, its role at the population level has not been examined. Inconsistencies between smoking susceptibility and prevalence data for Hispanics, NHAs, and ONHs could be explained by existing literature. Risk factors associated with smoking behavior (eg, peer smoking) are well documented and behave similarly across racial and ethnic groups.8 However, the distribution of youth exposure to risk factors is unfavorable to racial and ethnic minorities. For example, tobacco retail outlets are concentrated in Hispanic and foreign-born neighborhoods.23 Conversely, protective factors against smoking initiation have been understudied. For example, although our results show that equal proportions of NHAs and NHWs were susceptible to smoking after age 15 years, NHAs experience a host of social influences that are protective against cigarette smoking (eg, living in intact families, having fewer peers who smoke).24 To explain this paradox, research is needed to examine race- and ethnicity-specific factors that delay/inhibit smoking initiation or affect the rate of transition from susceptibility to smoking behavior.

Our results show differential changes in smoking susceptibility over time for racial and ethnic groups. NHB and NHA youth have become equally susceptible to smoking as their NHW counterparts. These results suggest a potential shift in the racial and ethnic composition of future smokers. This shift is concerning given the disparities racial and minority smokers endure with regard to cessation interventions (eg, screening, cessation aids)25 and subsequent health consequences of smoking.26 These results highlight the importance of tracking smoking susceptibility and use prevalence for all racial/ethnic groups. Studies exclude14 or collapse6 different racial and ethnic groups (eg, NHAs and ONHs) that differ on smoking onset, use patterns, and trajectories. In addition, researchers should strive to have adequate samples for minority populations.

Youths are more susceptible to smoking from 13 to 15 years old. This is supported by Chen and Unger’s study27 on the hazards of smoking initiation, whereby risk peaked at ages 11 to 14 years for all racial and ethnic groups, after which risk slowed except for Hispanics and Asian Americans. Our results on increased smoking susceptibility around ages 13 to 15 years coincide with data that show the average age of first cigarette use is 15.4 years,28 which supports the notion that susceptibility is a cognitive contemplation stage that precedes experimentation.10 We show different ages at which youths are most susceptible to smoking. However, these results do not perfectly align with the age of initiation for respective racial and ethnic groups. For example, compared with NHWs, we found that NHBs were most susceptible between ages 11 to 13 years. However, 1 study found that NHWs initiate smoking at age 15 years, whereas NHBs initiate smoking at age 16.1 years.9 Similarly, we found that Hispanics were more susceptible to smoking throughout adolescence, with peaks around ages 12 and 16.5 years. However, 1 study found that 42.3% of Hispanics initiate smoking between ages 14 to 17 years (vs 46.5% for NHWs).29 Consistent with our results on smoking susceptibility among NHAs, 1 study found that 47.8% of Asian and Pacific Islander regular smokers had initiated smoking between ages 18 to 21 years.29 Data are limited on initiation age for ONHs. These results confirm the need to examine transition from susceptibility to smoking behavior by race/ethnicity and how the duration of being susceptible to smoking affects the odds of smoking behavior.

Used as a screening tool, smoking susceptibility could help reduce smoking prevalence among youth. Interventions that strategically target never smokers who are most at risk for smoking initiation (rather than all nonsmokers) before smoking onset could be an effective smoking prevention measure. From an economic standpoint, targeting high-risk groups is cost effective compared with population-level interventions.30 From a public health standpoint, research shows interventions are effective in reducing initiation rates rather than improving quit rates.31 One potential venue to screen for and intervene with youth who are susceptible to smoking is at their annual medical exam where 62% to 83% of youth visit a primary care clinic within 1 to 2 years.32,33

Data are not generalizable beyond in-school students. In addition, smoking susceptibility was self-reported. However, studies have shown self-reported smoking behaviors, which are more stigmatized than smoking susceptibility, to be valid when compared with biomarkers (eg, Carbon Monoxide) among youths.34 We could not control for covariates that were absent (eg, socioeconomic status) or that inconsistently appeared (eg, exposure to tobacco magazine advertising) in the NYTS. The NYTS did not include subgroups of NHAs (eg, Chinese) who differ in smoking onset and prevalence. Due to the small sample size, we collapsed American Indians, Alaska natives, native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders into 1 group although these subpopulations differ in smoking onset and prevalence.26 We were less stringent in coding 1 susceptibility question, which could have resulted in underestimating susceptible youths from 2012 to 2014. However, to avoid introducing measurement artifact, we kept coding consistent from 1999 to 2014.

Conclusions

Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in smoking is a goal of the US Department of Health and Human Services in promoting health equity.35 A focus on youth susceptibility is fitting to reduce these disparities. Targeting youth when they are most susceptible to smoking with tailored prevention interventions could reduce smoking initiation, especially among racial/ethnic minorities.

Glossary

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- ONH

other non-Hispanic

- NHA

non-Hispanic Asian American

- NHB

non-Hispanic black

- NHW

non-Hispanic white

- NYTS

National Youth Tobacco Survey

- TVEM

time-varying effect modeling

Footnotes

Dr El-Toukhy conceptualized the study, carried out the main analyses, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Sabado prepared the dataset, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed the final manuscript; Dr Choi coordinated and supervised data analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The effort of Drs El-Toukhy, Sabado, and Choi was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fast facts. Available at: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/. Accessed March 16, 2016

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012:3 [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2010:2. [PubMed]

- 4.Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA. New methods shed light on age of onset as a risk factor for nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2015;50:161–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychol. 2000;19(3):223–231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White HR, Nagin D, Replogle E, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Racial differences in trajectories of cigarette use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(3):219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandel DB, Kiros G-E, Schaffran C, Hu MC. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):128–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandel D, Schaffran C, Hu M-C, Thomas Y. Age-related differences in cigarette smoking among whites and African-Americans: evidence for the crossover hypothesis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118(2-3):280–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15(5):355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unger JB, Johnson CA, Stoddard JL, Nezami E, Chou CP. Identification of adolescents at risk for smoking initiation: validation of a measure of susceptibility. Addict Behav. 1997;22(1):81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang M, Hollis J, Polen M, Lapidus J, Austin D. Stages of smoking acquisition versus susceptibility as predictors of smoking initiation in adolescents in primary care. Addict Behav. 2005;30(6):1183–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Toukhy S, Choi K. Smoking-related beliefs and susceptibility among United States youth nonsmokers. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(4):448–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2015: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016

- 15.Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59(suppl 1):S61–S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS). Available at: www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm. Accessed February 1, 2016

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services Minority population profiles. Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=26. Accessed June 17, 2016

- 18.Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, et al. Investing in youth tobacco control: a review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tob Control. 2000;9(1):47–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang B, King BA, Corey CG, Arrazola RA, Johnson SE. Awareness and use of non-conventional tobacco products among U.S. students, 2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2 suppl 1):S36–S52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Dziak JJ, Butera NM. Trends among U.S. high school seniors in recent marijuana use and associations with other substances: 1976–2013. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):198–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arrazola RA, Kuiper NM, Dube SR. Patterns of current use of tobacco products among U.S. high school students for 2000-2012–findings from the National Youth Tobacco Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(1):54–60.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrett BE, Dube SR, Trosclair A, Caraballo RS, Pechacek TF; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Cigarette smoking - United States, 1965-2008. MMWR Suppl. 2011;60(1):109–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novak SP, Reardon SF, Raudenbush SW, Buka SL. Retail tobacco outlet density and youth cigarette smoking: a propensity-modeling approach. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):670–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson RA, Hoffmann JP. Adolescent cigarette smoking in U.S. racial/ethnic subgroups: findings from the National Education Longitudinal Study. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(4):392–407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cokkinides VE, Halpern MT, Barbeau EM, Ward E, Thun MJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in smoking-cessation interventions: analysis of the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(5):404–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Health and Human Services Tobacco Use Among US Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups - African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, Unger JB. Hazards of smoking initiation among Asian American and non-Asian adolescents in California: a survival model analysis. Prev Med. 1999;28(6):589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The Health Consequences of Smoking - 50 years of progress. A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014

- 29.Trinidad DR, Gilpin EA, Lee L, Pierce JP. Do the majority of Asian-American and African-American smokers start as adults? Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(2):156–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens W, Thorogood M, Kayikki S. Cost-effectiveness of a community anti-smoking campaign targeted at a high risk group in London. Health Promot Int. 2002;17(1):43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prokhorov AV, Kelder SH, Shegog R, et al. Impact of A Smoking Prevention Interactive Experience (ASPIRE), an interactive, multimedia smoking prevention and cessation curriculum for culturally diverse high-school students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(9):1477–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Connor EA, Hollis JF, Polen MR, Lichtenstein E. Adolescent health care visits: opportunities for brief prevention messages. Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2(6):272–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farber HJ, Groner J, Walley S, Nelson K; SECTION ON TOBACCO CONTROL . Protecting Children From Tobacco, Nicotine, and Tobacco Smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5). Available at : www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/136/5/e1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wills TA, Cleary SD. The validity of self-reports of smoking: analyses by race/ethnicity in a school sample of urban adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(1):56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed March 11, 2016