Abstract

BACKGROUND

Systematic symptom assessment is not routinely performed in pediatric oncology. The objectives of the current study were to characterize the symptoms of pediatric oncology outpatients and evaluate agreement between patient and proxy reports and the association between children’s ratings and oncologists’ treatment recommendations.

METHODS

Two versions of the pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (pMSAS) were translated into Spanish. An age-appropriate and language-appropriate pMSAS was administered independently before visits to the oncologist to patients and family caregivers (caregivers) and after visits to consenting oncologists. Statistical analysis included Spearman correlation coefficients and weighted kappa values.

RESULTS

English and Spanish results were similar and were combined. A total of 60 children and their caregivers completed the pMSAS. The children had a median age of 10 years (range, 7–18 years); approximately 62% were male and 33% were Spanish-speaking. Fourteen oncologists completed the pMSAS for 25 patients. Nine patients (15%) had no symptoms and 38 patients (63%) reported ≥2 symptoms. The most common symptoms were fatigue (12 patients; 40%) and itch (9 patients; 30%) for the younger children and pain (15 patients; 50%) and lack of energy (13 patients; 45%) among the older children. Total and subscale score agreement varied by proxy type and subscale, ranging from fair to good for most comparisons. Agreement for individual symptoms between the patient and proxy ranged from a kappa of −0.30 (95% confidence interval, −0.43 to −0.01) to 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.75 to 1.00). Three of 51 symptomatic patients (6%) had treatment recommendations documented in the electronic health record.

CONCLUSIONS

Symptoms are common and cross several functional domains. Proxy and child reports are often not congruent, possibly explaining apparent undertreatment among this group of patients.

Keywords: caregiver, child, neoplasm, patient experience, symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Adults receiving treatment for advanced cancer experience a high symptom burden,1–6 but to our knowledge only limited data are available for pediatric patients with cancer that suggest the same.1,7–15 It is important to note that parental perceptions of suffering and poor symptom control are associated with distress16 that can persist for years after bereavement.8,17

Descriptive data and systematic symptom surveys have indicated that clinicians are often unaware of the symptom burden their patients experience.7,18–20 Described largely for pain,21–23 numerous patient-associated, clinician-associated, and institutional barriers exist that impact pain and non-pain symptom assessment for adults and children. Barriers include knowledge and training deficits, time constraints, care setting, language and cultural disparities, and the paucity of validated pediatric tools dedicated to the assessment of multiple symptoms.24–28

Reliance on proxy raters for symptom reports is higher for children than adults. The accuracy of proxy raters has not been well established in either population, but appears to vary with symptom and rater type.29,30 In adult populations, caregivers typically overestimate, and clinicians typically underestimate, the intensity of pain and other symptoms compared with patients.31–33 Agreement is closer for more visible symptoms such as immobility than for less visible symptoms such as pain, feelings, or thoughts.10,11,34,35 Collins et al reported variable agreement of child-parent symptom reports, depending on the symptom evaluated. A symptom checklist, rather than a parent-completed version of the pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (pMSAS), was used to determine agreement.10,11

Scant data exist regarding symptom prevalence or agreement of child-proxy symptom reports for children with advanced cancer. Data using Spanish language symptom assessment scales are even more limited; at the time of the inception of the current study, we could not identify validated assessment tools for multiple symptoms. Prior adult experience supports the value of systematic symptom assessment for identifying symptoms and management strategies at the patient and system levels.36 Better clinician understanding of symptom burden and of factors associated with differences in symptom reports between patient and proxy raters has the potential to improve symptom management in this underserved population.

The main objectives of the current study were to characterize symptom profiles of children with advanced cancer and to evaluate the agreement of symptom assessment between different types of proxy raters. Secondarily, we evaluated the association between child-oncologist symptom agreement and symptom management recommendations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The current Institutional Review Board-approved study was a cross-sectional pilot of pediatric oncology outpatients at a single comprehensive cancer center. Eligible children were aged 7 to 18 years, had a diagnosis of advanced cancer (recurrent, metastatic, or progressive), were established patients in the division of pediatrics, spoke and understood English or Spanish, and had an available caregiver who spoke the same language. Eligible caregivers were parents or legal guardians of eligible children. Eligible physicians were the child’s attending oncologist or fellow physician.

Instruments

Pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

Pediatric versions of the MSAS,4 which evaluates physical and psychological symptoms, have been validated in English for children aged 7 to 12 years (pMSAS 7–12)11 and those aged 10 to 18 years (pMSAS 10–18)10 (see online Supporting Information Figs. 1 and 2). The pMSAS 10–18 evaluates 30 items and the pMSAS 7–12 evaluates 8 items. In addition to individual symptom scores, the average of frequency, intensity, and distress, both versions of the pMSAS provide a total score (TOTAL), calculated as the average of the summed symptom scores. The pMSAS 10–18 also provides 3 subscale scores: the Global Distress Index, the physical symptom subscale (PHYS), and the psychological symptom subscale (PSYCH). Their α coefficients are .85, .87, and .83, respectively.10,11

For the current study, we independently developed neutral Spanish language versions of the pMSAS 7–12 and pMSAS 10–18 using established methods of forward and back translation. English-language versions were translated into Spanish by a professional medical translator whose native language was Spanish and back-translated into English by a second professional medical translator whose native language was English. For back-translations that did not agree with the original, the first translator provided a second translation. The process was repeated until both versions matched the original English version.37–39

Procedures

After obtaining the permission of the oncologist, patients and caregivers were approached by the research staff. Once informed written consent/assent was obtained and before the oncologist visit, the age and language-appropriate version of the pMSAS was administered to the child and separately to the caregiver for the rater’s perception of the child’s symptoms over the past 48 hours. If children were uncomfortable with having the caregiver leave the room, caregivers completed their survey first, before the child. Children aged 7 to 10 years were administered the pMSAS 7–12 and those aged 11 to 18 years completed the pMSAS 10–18. Consenting oncologists completed the corresponding English-language pMSAS version after the patient’s visit. Patient and caregiver assessments were then provided to the oncologist to facilitate symptom management. Children and parents were told that the questionnaires would not be provided to the oncologist until after the physician visit.

Patient demographics, clinical information, and symptom management recommendations were extracted from the electronic health record. Caregivers provided their own demographic information. Symptom management recommendations were identified from the electronic health record.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed descriptively using graphics, percentages, means, medians, and appropriate measures of dispersion. Pairwise agreement of symptom assessment between child and caregiver, child and the treating oncologist, and caregiver and the treating oncologist was evaluated using weighted kappa coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). For the TOTAL, PHYS, and PSYCH subscales and the Global Distress Index of the pMSAS 10–18, we calculated Spearman correlation coefficients. Using logistic regression analysis, we further tested the 3 rater types simultaneously for each outcome; patients were omitted from the analysis if any outcome measure was missing.

A sample size of 60 patient-caregiver dyads was selected because with a total of 30 dyads per age group, correlations of ±0.5 or greater could be declared as statistically significant within subgroups, assuming a 2-sided significance level of .05 and 80% power.

RESULTS

Of the 202 age-appropriate patients with advanced disease diagnosed during the study period (September 2009–April 2011), 64 patients were missed by the research team. Physicians declined permission for 12 patients (6%), most often due to the intended delivery of bad news (6 of 12 patients; 50%). Twenty-nine patients were ineligible due to language or other criteria. For an additional 27 patients, their age-specific and language-specific cohort was complete at the time of presentation to the study institution. Of 70 eligible patient-caregiver dyads, 8 declined, yielding an 89% recruitment rate. Two dyads were subsequently found to be ineligible due to incorrect assessments, leaving 60 dyads for analysis. Fourteen physicians participated, ranging in experience from fellow to professor. All were fully fluent in English; professional medical translators were incorporated into care for non-Spanish-speaking physicians of Spanish-speaking families.

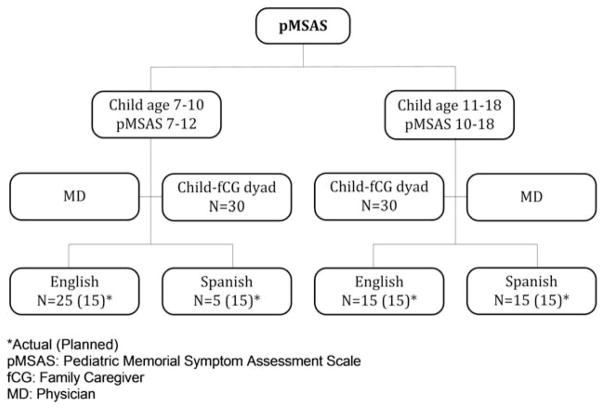

The English and Spanish results were similar, and therefore were combined. The only differences found were for the older patient group; patients assessed in English reported pain more frequently and those assessed in Spanish reported irritability more often (P =.03 and .01, respectively). Due to lower than expected numbers of Spanish-speaking children in the younger age group, the protocol was amended to allow 30 English-speaking or Spanish-speaking children in this group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Symptom profiles study plan. Asterisk indicates actual (planned); fCG, family caregiver; MD, physician; pMSAS, pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale.

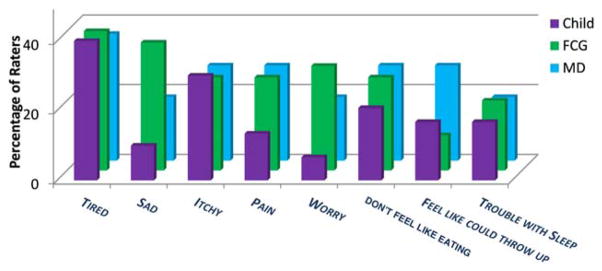

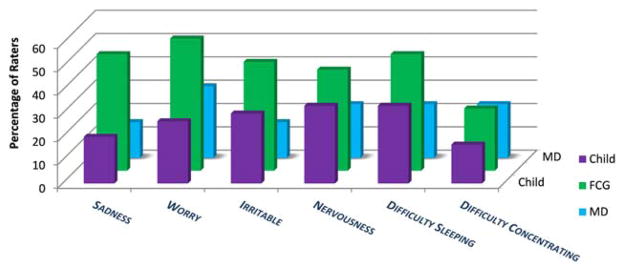

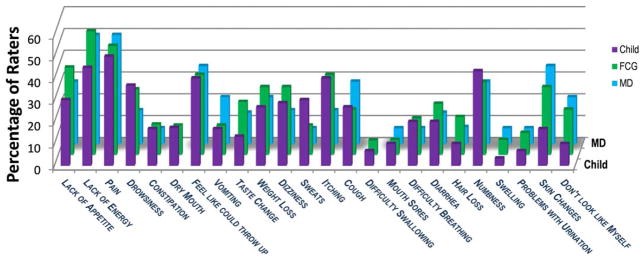

The median patient age was 10 years (range, 7–18 years) and the median age for caregivers was 39 years (range, 25–67 years). Most caregivers were married or partnered and had some college education. All caregivers were parents except for 1 legal guardian (the child’s grandmother). The majority of children received active treatment. None received palliative care. Demographics and disease and treatment characteristics are shown in Supporting Information Tables 1 and 2. Overall, 15% of the children (9 of 60 children) had no symptoms and 63% of the children (38 of 60 children) reported ≥2 symptoms. The median number of symptoms per child as reported by the rater and pMSAS version is shown in Supporting Information Table 3. For child-reported symptoms, the median number was 1 (range, 0–4 symptoms) and 6 (range, 0–18 symptoms), respectively, for the younger and older patient groups. Younger children most commonly reported “tired” (12 of 30 patients; 40%) and “itch” (9 of 30 patients; 30%) and older children most often reported “pain” (15 of 30 patients; 50%) and “lack of energy” (13 of 29 patients; 45%) (Figs. 2–4). Symptom frequency as reported among different rater types was not found to be significantly different except for sadness in the older group, with caregivers more frequently reporting sadness than patients (odds ratio, 3.77; 95% CI, 1.21–11.71 [P =.02]). Interrater agreement for TOTAL and subscale scores ranged from fair to good for children and caregivers, with correlation of child-caregiver ratings found to be least strong for the PSYCH subscale at 0.46. Interrater agreement for individual symptom scores was highly variable (Table 1), with pairwise correlation ranging from a kappa of −0.30 (95% CI, −0.43 to −0.01) to 0.91 (95% CI, 0.75 to 1.00). There was no significant association noted between caregiver income or educational level and child-caregiver symptom agreement. Caregiver-oncologist ratings did not correlate (Table 2). Of 51 symptomatic patients, 3 (6%) had documented symptom management recommendations.

Figure 2.

Symptom prevalence by rater (pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for children aged 7 to 12 years [pMSAS 7–12]). No statistically significant difference was noted between raters. fCG indicates family caregiver; MD, physician.

Figure 4.

Individual psychological symptom prevalence by rater (pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for children aged 10 to 18 years [pMSAS 10–18]). No statistically significant difference was noted between raters except for more frequent reports of sadness by family caregivers (fCGs) compared with children (odds ratio, 3.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.21–11.71 [P =.02]). MD indicates physician.

TABLE 1.

Pairwise Correlation of Proxy Rater Scores for Individual Symptoms (pMSAS 10–18)

| Scores | Raters | Prevalence | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| (No. of Dyads) | Weighted Kappa (95% CI) | Weighted Kappa (95% CI) | |

| Pain | Pt-CG (30) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) |

| Pt-MD (14) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.0) | 0.7 (0.4 to 0.9) | |

| Lack of energy | Pt-CG (29) | 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.6) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.5) |

| Pt-MD (14) | 0.1 (−0.4 to 0.6) | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.5) |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; pMSAS 10–18, pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for patients aged 10–18 years; Pt-CG, patient-caregiver; Pt-MD, patient-physician.

TABLE 2.

Pairwise Correlation of Proxy Rater Scores for Older Children (pMSAS 10–18)

| Score | Child-fCG | Child-MD | fCG-MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| R (P) | R (P) | R (P) | |

| N=30 | N=14 | (N=14) | |

| Total | 0.67 (<.0001) | 0.60 (.02) | 0.47 (NS) |

| PHYS | 0.64 (.0001) | 0.60 (.02) | 0.39 (NS) |

| PSYCH | 0.46 (.01) | 0.61 (.03) | 0.12 (NS) |

| GDIa | 0.51 (.01) | 0.54 (NS) | 0.35 (NS) |

Abbreviations: fCG, family caregiver; GDI, Global Distress Index; MD, physician; NS, not statistically significant; PHYS, physical symptom subscale; pMSAS 10–18, pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for patients aged 10–18 years; PSYCH, psychological symptom subscale; R, Spearman correlation coefficient.

Child-fCG: 25 cases; child-MD: 12 cases; fCG-MD: 11 cases.

DISCUSSION

The current study data add to the growing literature suggesting that children with advanced cancer are polysymptomatic. Multiple symptoms have been noted in patients with cancers of various stages,7,12–14,40,41 with differences in prevalence likely related to methodological issues, treatment status, and the population studied.1 For example, we used a validated patient self-report of outpatients with advanced disease, the majority of whom were receiving active treatment, rather than retrospective symptom recall by bereaved parents.7 It is important to note that Williams et al15 reported higher symptom prevalence than the current study. Unlike the pMSAS, the assessment tool used in their study was developed specifically to evaluate treatment-associated symptoms; children with all stages of disease were included, the time frame for evaluation was longer, and nearly 60% of symptom reports for patients aged 5 to 11 years were nurse proxy ratings and not reported by the child.15 Similar to the current study, Williams et al found lower symptom prevalence in younger children.15 We were unable to evaluate the association between symptoms and treatment type due to small subset numbers.

Agreement of the child-proxy symptom report did not appear to vary by language, caregiver income, or caregiver educational level in this exploratory analysis. For TOTAL and the subscales, agreement ranged from fair to good, and was found to be least strong for child-caregiver PSYCH ratings. However, interrater agreement was highly variable for individual symptoms, with a trend for caregivers to estimate more psychological symptoms than did children, a finding that is to be confirmed in future studies. It is particularly interesting that sadness or worry was scored relatively low by children compared with parents. Overall, caregivers suspected higher emotional distress than was reported by children. Addressing the incongruence through open communication may be a beneficial and necessary step to determine who in the family needs what type of intervention. Baggott et al noted similar findings with regard to parental overestimation of psychological symptoms in dyadic ratings of children evaluated during the week of chemotherapy.40 In non-cancer settings, Varni et al42 reported higher parent-child item-level discrepancies for items measuring internal states or less observable items such as fatigue, as evaluated using pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure Information System (PROMIS) scales pertaining to quality of life. Contrary to the results of the current study, Varni et al found poor agreement for psychological items, with parents underestimating these items compared with children.42

We found no agreement of caregiver-oncologist sub-scale scores, and no association between child-oncologist agreement of symptom report and treatment recommendations. Lack of agreement between caregivers and oncologists may reflect a difference in symptoms evaluated by the standard system reviews versus systematic symptom screening with the pMSAS, failure of caregiver-physician communication related to contextual factors such as visit prioritization for treatment purposes, limited physician experience in symptom assessment, or cultural and linguistic barriers, although all oncologists were proficient in English and translators were readily available. Similarly, the paucity of documented symptom management recommendations for child-elicited symptoms may reflect incomplete documentation or oncologist failure to identify symptoms and/or appreciate the availability of effective treatment approaches.

Lack of systematic assessment presents a barrier to care, because symptoms must be identified to be addressed. The systematic use of symptom assessment scales improves symptom identification in adult populations,18,19 but data in pediatric populations are lacking. Few pediatric assessment tools evaluate multiple symptoms for cancer1,28,40,43–46 or non-cancer chronic conditions. The current study is among the first to systematically document symptom prevalence in a routine pediatric outpatient oncology care setting using a validated tool specifically designed to assess multiple symptoms across several functional domains. It is also among the first to concurrently obtain child and parent reports. Symptom prevalence for pediatric outpatients with advanced disease was noteworthy and easily detected using a relatively brief, self-administered measure. One limitation of the pMSAS is that a count of symptom scores does not reflect the relevance and interdependence of individual symptoms. More research is needed to characterize the interaction of different symptoms and their relevance. The smaller number of symptoms reported by younger children may be related in part to the child’s age and the scales used because the pMSAS 7–12 evaluated fewer symptoms than the pMSAS 10–18. Symptom profiles in younger children may be better clarified with developmentally appropriate scales derived with input from the children themselves, rather than by a modification of adult scales.

There were several limitations to the current study. Participants were from a single National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center and caregivers were predominantly mothers with relatively high educational and income levels, thereby limiting the generalizability of study findings. However, pediatric cancer is often treated in specialized settings,47 caregivers for children and adults are more likely to be women,48–50 and caregivers without any formal education and with low incomes were represented, thus supporting the generalizability of the current study results.

Despite lower than planned recruitment, Spanish-speaking and Hispanic patients were well represented in the current study compared with their percentages within the patient population. Other potential limitations include the implicit assumption that pMSAS proxy versions were equivalent to child-reported versions; a lack of validation of the Spanish tool; and potential issues related to the timing of the administration of the pMSAS, with children and caregivers completing the pMSAS before and oncologists completing it after the clinical encounter. Established techniques were used to translate the pMSAS, but rigorous testing of the Spanish version was not conducted. Notably, no consensus currently exists regarding how to achieve quality instrument translation in cross-cultural research.37–39 The administration of the pMSAS to patients and caregivers before the oncologist visit may have influenced symptom communication to the oncologist, but children and caregivers were aware that the oncologists would not receive their pMSAS results until after their visit. Last, oncologists frequently did not participate, most typically due to time constraints. The small sample size for oncologist-proxy comparisons resulted in larger variance and thus wider 95% CIs around the kappa estimates, with a reduced ability to detect statistically significant differences for physician comparisons. Small physician numbers, compounded by ascertainment of symptom recommendations by chart review, may have precluded the detection of an association between symptom reports and treatment recommendations, because physician visits often encompass more than what is documented. The pMSAS has the potential to improve documentation and/or facilitate the communication of symptoms, with implications for improving patient care and appropriate reimbursement. However, more research is needed to determine how best to encourage its clinical adoption and use.

The strengths of the current study were numerous and included the simultaneous evaluation of multiple symptoms using a validated assessment tool specifically designed for that purpose, the large number of children evaluated in a routine clinical setting, and the inclusion of proxy raters commonly involved in care. The relatively high participation rate of Spanish-speaking and Hispanic individuals was also informative, because little is known regarding this underserved population.

As a priority to improve symptom management, the results of the current study underscore the importance of systematic symptom screening and of eliciting both child and caregiver reports to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the symptom experience. Symptom burden has been associated with impaired well-being, quality of life, and psychological distress in pediatric patients with cancer. In adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer, symptom burden is also associated with higher social information needs with regard to talking about their cancer experience and meeting peer survivors.51 Poor symptom control is a source of parental distress, including bereaved parents.6,8,52 Parents of children with advanced cancer who perceived their child was suffering due to symptoms or treatment were more likely to have higher levels of psychological distress than those that did not.16 In turn, parental distress often has a negative psychological impact on pediatric patients and their siblings.53,54

The recognition of symptoms is a prerequisite for treatment, but is insufficient to improve symptom management. A recent longitudinal study evaluating the impact of patient feedback and parent-reported outcomes to pediatric oncologists did not demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in pMSAS symptom scores.41 Other studies have also noted that clinician feedback of symptom scores does not routinely lead to improved symptom management. The reasons for this are complex and require further elucidation, but may reflect a failure to appreciate the impact on the patient and/or family, inadequate training in symptom management, lack of effective treatment modalities, or the limited availability/ use of consulting services such as palliative care or pain management.

A critical next step is the incorporation of evidence-based practices into clinical care by the primary clinician or by referral to specialist groups to evaluate how treatments alter symptom outcomes. We need to use effective strategies when they exist and develop new ones otherwise. Given the imperfect association between proxy rater symptom reports and those of the child and adolescent and the different perspective each has to offer, the regular assessment of patient-reported outcomes, complemented by proxy reports, is crucial to care. Understanding differences underlying symptom reports, without trying to make them agree, is key to avoiding undertreatment or overtreatment. Further research is needed to characterize each perspective when rater assessments differ to enhance understanding of the symptom experience and potentially improve management strategies. More research into language and cultural contributions to symptom assessment is also needed.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Individual physical symptom prevalence by rater (pediatric Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for children aged 10 to 18 years [pMSAS 10–18]). No statistically significant difference was noted between raters. fCG indicates family caregiver; MD, physician.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children, parents, clinicians, and research team. We also thank the American Cancer Society, whose participation made this work possible, and Brittany Cullen for her expert administrative support.

FUNDING SUPPORT

Supported by an American Cancer Society pilot and exploratory research grant (PEP:08-272-01-PC1).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Dr. Bruera was partly supported by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center support grant CA016672.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Baggott C, Dodd M, Kennedy C, Marina N, Miaskowski C. Multiple symptoms in pediatric oncology patients: a systematic review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2009;26:325–339. doi: 10.1177/1043454209340324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh D, Donnelly S, Rybicki L. The symptoms of advanced cancer: relationship to age, gender, and performance status in 1,000 patients. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:175–190. doi: 10.1007/s005200050281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strasser F, Sweeney C, Willey J, Benisch-Tolley S, Palmer JL, Bruera E. Impact of a half-day multidisciplinary symptom control and palliative care outpatient clinic in a comprehensive cancer center on recommendations, symptom intensity, and patient satisfaction: a retrospective descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:481–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh D, Zhukovsky DS. Communication in palliative medicine: a pilot study of a problem list to capture complex medical information. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21:365–371. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seow H, Barbera L, Sutradhar R, et al. Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1151–1158. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, Bjork O, Steineck G, Henter JI. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9162–9171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9155–9161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins JJ, Byrnes ME, Dunkel IJ, et al. The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:363–377. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins JJ, Devine TD, Dick GS, et al. The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: the validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7–12. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:10–16. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2136–2145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen-Gogo S, Marioni G, Laurent S, et al. End of life care in adolescents and young adults with cancer: experience of the adolescent unit of the Institut Gustave Roussy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2735–2741. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalmsell L, Kreicbergs U, Onelov E, Steineck G, Henter JI. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1314–1320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams PD, Williams AR, Kelly KP, et al. A symptom checklist for children with cancer: the Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist-Children. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:89–98. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821a51f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg AR, Dussel V, Kang T, et al. Psychological distress in parents of children with advanced cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:537–543. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala K, Wolfe J. Systematic review of psychosocial morbidities among bereaved parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:503–512. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homsi J, Walsh D, Rivera N, et al. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:444–453. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White C, McMullan D, Doyle J. “Now that you mention it, doctor…”: symptom reporting and the need for systematic questioning in a specialist palliative care unit. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:447–450. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhukovsky DS, Herzog C, Kaur G, Palmer JL, Bruera E. The impact of palliative care consultation on symptom assessment, communication needs, and palliative interventions in pediatric patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:343–349. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilden JM, Himelstein BP, Freyer DR, Friebert S, Kane JR. End-of life care: special issues in pediatric oncology. In: Foley KM, Gelbrand H, editors. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. pp. 161–198. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen M, Mendoza T, Gning I, Neumann J, Giralt S, Cleeland C. Ethnic differences in pain and other symptoms associated with blood or marrow transplantations. J Pain. 2004;5:104. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MZ, Easley MK, Ellis C, et al. Cancer pain management and the JCAHO’s pain standards: an institutional challenge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:519–527. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilden JM, Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, et al. Attitudes and practices among pediatric oncologists regarding end-of-life care: results of the 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:205–212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Levels of symptom burden during chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer: differences between public hospitals and a tertiary cancer center. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2859–2865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu OS, Crew KD, Jacobson JS, et al. Ethnicity and persistent symptom burden in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:241–250. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macartney G, Stacey D, Carley M, Harrison MB. Priorities, barriers and facilitators for remote support of cancer symptoms: a survey of Canadian oncology nurses [in English, French] Can Oncol Nurs J. 2012;22:235–247. doi: 10.5737/1181912x224235240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dupuis LL, Ethier M, Tomlinson D, Hesser T, Sung L. A systematic review of symptom assessment scales in children with cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:430–435. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobchuk M. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: modified for use in understanding family caregivers’ perceptions of cancer patients’ symptom experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:644–654. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94:2090–2106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobchuk MM, Vorauer JD. Family caregiver perspective-taking and accuracy in estimating cancer patient symptom experiences. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2379–2384. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigurdardottir V, Brandberg Y, Sullivan M. Criterion-based validation of the EORTC QLQ-C36 in advanced melanoma: the CIPS questionnaire and proxy raters. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:375–386. doi: 10.1007/BF00433922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruera E, Willey JS, Ewert-Flannagan PA, et al. Pain intensity assessment by bedside nurses and palliative care consultants: a retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:228–231. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall JM. Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:95–109. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varni JW, Katz ER, Seid M, Quiggins DJ, Friedman-Bender A, Castro CM. The Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory (PCQL). I. Instrument development, descriptive statistics, and cross-informant variance. J Behav Med. 1998;21:179–204. doi: 10.1023/a:1018779908502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Patterns of childhood death in America. In: Field JM, Behrman RE, editors. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 41–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cull A, Sprangers M, Bjordal K, Aronson N, West K, Bottomley A on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC Monograph. 2. Brussels, Belgium: EORTC; 2002. Translation Procedure. Available at: http://ipenproject-org.heracen-ter.org/documents/methods_docs/Surveys/EORTC_translation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: a methods review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acquadro C, Conway K, Hareendran A, Aaronson N European Regulatory Issues and Quality of Life Assessment (ERIQA) Group. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health. 2008;11:509–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baggott C, Cooper BA, Marina N, Matthay KK, Miaskowski C. Symptom assessment in pediatric oncology: how should concordance between children’s and parents’ reports be evaluated? Cancer Nurs. 2014;37:252–262. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1119–1126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varni JW, Thissen D, Stucky BD, et al. Item-level informant discrepancies between children and their parents on the PROMIS® pediatric scales [published online ahead of print January 6, 2015] Qual Life Res. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0914-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Docherty SL. Symptom experiences of children and adolescents with cancer. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2003;21:123–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kestler SA, Lobiondo-Wood G. Review of symptom experiences in children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:E31–E49. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182207a2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raper JT, Perkin RM. Symptoms in dying children. In: Perkin RM, Swift JD, Newton DA, Anas NG, editors. Pediatric Hospital Medicine: Textbook of Inpatient Management. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klassen AF, Anthony SJ, Khan A, et al. Identifying determinants of quality of life of children with cancer and childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1275–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Family Caregiver Alliance National Center on Caregiving. [Accessed May 15, 2015];Selected caregiver statistics. Available at: http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=439.

- 49.AARP Research. [Accessed May 15, 2015];Caregiving in the US. 2009 Available at: http://www.aarp.org/relationships/caregiving/info-12-2009/caregiving_09.html.

- 50.National Alliance for Caregiving in collaboration with AARP. [Accessed May 15, 2015];Caregivers of children: a focused look at those caring for a child with special needs under the age of 18. Available at: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/caregiving_09_children.pdf.

- 51.Kent EE, Smith AW, Keegan TH, et al. Talking about cancer and meeting peer survivors: social information needs of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2:44–52. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poder U, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Parents’ perceptions of their children’s cancer-related symptoms during treatment: a prospective, longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;40:661–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prchal A, Landolt MA. How siblings of pediatric cancer patients experience the first time after diagnosis: a qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:133–140. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821e0c59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilkins KL, Woodgate RL. A review of qualitative research on the childhood cancer experience from the perspective of siblings: a need to give them a voice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22:305–319. doi: 10.1177/1043454205278035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.