Abstract

Aims and objectives

Although clopidogrel combined with aspirin is the most commonly used dual drug combination to avert thrombotic events in patients with coronary artery disease, the poor responsiveness to clopidogrel remains a concern. The objective of the current study is to assess the extent of resistance to clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor in a real life set of patients with coronary artery disease who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Materials and methods

A total of 539 patients, who underwent PCI and were on aspirin and on any of the three drugs, namely, clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor, were followed up regularly in the outpatient department. After 24 h of initiation of antiplatelet medication, response to the treatment in all the patients was assessed using thrombelastography. The average percentage platelet inhibition was assessed along with the resistance and sensitivity to the drug in each patient. Sensitivity and resistance to the specific drug was defined as >50% and <50% of mean platelet inhibition, respectively.

Results

About 99.15% of the patients treated with ticagrelor were sensitive to the drug and the difference between ticagrelor, clopidogrel, and prasugrel groups for sensitivity was significant with a p value of 0.00001, in favor of ticagrelor. It was also found that ticagrelor was significantly (p value of 0.001) associated with least resistance as compared with the other drugs assessed in the study.

Conclusions

Use of ticagrelor as dual therapy along with aspirin in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and undergoing PCI was associated with a significantly higher mean percentage platelet inhibition, higher sensitivity, and lower resistance as compared with the usage of clopidogrel or prasugrel.

Keywords: Ticagrelor, Clopidogrel, Prasugrel, Drug resistance, Percutaneous coronary intervention

1. Introduction

The Million Death Study reported that cardiovascular disease (CVD) was responsible for 30% mortality in males and 25% mortality in females in India.1 In 2008, of the >2.5 million deaths due to CVD in India, two-thirds were due to coronary heart disease (CHD) indicating the rapidly escalating burden.2

2. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and role of platelets

As the primary critical step in hemostasis, platelets are activated in the presence of an agonist in response to vessel injury. The further platelet cascade involving adhesion, activation, and aggregation is depicted in Fig. 1.3

Fig. 1.

Platelet activation in response to agonist.

2.1. Methods for platelet function tests4

The various types of platelet function tests are compared in Table 1.

Table 1.

Platelet function tests.4

| Test | Method |

|---|---|

| Light transmission aggregometry | Used to measure low-shear, platelet-to-platelet aggregation |

| VerifyNow™ | Fully automated |

| Measures levels of antiplatelet therapy | |

| Flow cytometry | Uses whole-blood samples |

| Measures platelet glycoproteins and activation markers | |

| Uses light-emitting fluorescence to detect platelet activation | |

| Flow cytometry using VASP assay | Monitors P2Y12 platelet receptor inhibition |

| PFA-100® | Assesses high-shear platelet adhesion and aggregation |

2.2. Thromboelastography (TEG)5

The TEG Platelet Mapping assay relies on evaluation of clot strength to enable a quantitative analysis of platelet function. TEG analysis provides the measure of maximum platelet function, and hence the degree of hypercoagulability and extent of inhibition needed to make the platelet therapy personalized and helps deduce the:

-

•

Resistance to and effect of antiplatelet therapy.

-

•

Therapeutic level of the therapy.

-

•

Risk for ischemic or bleeding event.

2.3. Currently available antiplatelet agents

2.3.1. Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel is a pro-drug, which binds to P2Y12 receptors irreversibly, rendering the receptor unable to respond to adenosine diphosphate (ADP), thus reducing platelet function.6 Its effect on platelet function lasts for the lifetime of the affected platelet. It has a slow onset of action and is associated with high interindividual variability with high platelet reactivity despite treatment and resistance during long-term therapy.

These factors make it difficult to predict the degree of antiplatelet response to clopidogrel. The Gauging Responsiveness with A VerifyNow assay—Impact on Thrombosis and Safety (GRAVITAS) trial evaluated the effects of increasing the dose of clopidogrel in patients with inadequate inhibition of platelet function on standard dose treatment and noted that some patients continued to have very high platelet reactivity on higher doses of clopidogrel.7

2.3.2. Prasugrel

Prasugrel is a thienopyridine and a pro-drug that needs to be converted to an active metabolite. Prasugrel attains inhibition of platelet aggregation (IPA) within 15–30 min after a loading dose of 60 mg and attains a maximum IPA of 60–70% within 2–4 h. The IPA during maintenance treatment is at an average of 50%.7

Prasugrel binds to the P2Y12 receptors irreversibly and produces inhibition of platelet function for the lifetime of the affected platelet. Prasugrel effects are much more predictable as revealed in the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI) study.7

Although prasugrel resistance has not been reliably described, some studies have demonstrated prasugrel resistance. Bonello et al. reported a high rate of prasugrel resistance using the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein index.8 Silvano et al. described a rare case of both clopidogrel and prasugrel resistance in a patient without diabetes, with acute STEMI due to stent thrombosis.9 Morel et al. also observed prasugrel ‘resistance’ in 19% of cases with CKD.10

2.3.3. Ticagrelor

Ticagrelor is a directly acting cyclopentyltriazolo-pyrimidine (CPTP) class molecule, which does not require conversion into an active metabolite. It reversibly inhibits the P2Y12 receptors on platelets.

Ticagrelor results in an average IPA of 80–90% at 2–4 h after 180 mg loading dose. The IPAs achieved by ticagrelor were higher than the IPA typically seen with clopidogrel of around 50%.11

The end result of PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, which was a head-to-head comparison of ticagrelor and clopidogrel in hospitalized patients with an ACS, saw a significant reduction in the composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and stroke with ticagrelor without any difference in the overall incidence of fatal or major bleeding. This was the first time that an OAP agent (ticagrelor) resulted in a significant reduction in the overall death rate. Moreover, the PLATO PlateLET substudy demonstrated that antiplatelet effect both during initiation of treatment and maintenance therapy was significantly higher with ticagrelor than with clopidogrel.7

2.3.4. Clopidogrel resistance

Clopidogrel resistance can be defined as the failure of therapy in patients for whom clopidogrel does not achieve significant platelet inhibition and results in recurrent ischemic events.12 Numerous studies using different platelet function tests provided estimates of the prevalence ranging from 16.8% to 21% for clopidogrel resistance.13

Variable response to clopidogrel is well documented but a standardized definition for individual responsiveness to clopidogrel is not present. Nonetheless, the common terminologies used are “low-responder,” “hyporesponder,” “semiresponder,” and “suboptimal responder”.13 In general, patients showing <70% but >30% aggregation are defined as hyporesponders and <30% aggregation as resistant.14

2.3.4.1. Clopidogrel resistance: global and Indian data

Several international studies on clopidogrel resistance showed 5–44% of clopidogrel resistance in patients who underwent PCI (Table 2). The Indian data also correspond to the international data with a similar prevalence of clopidogrel resistance (Table 3).

Table 2.

Observed clopidogrel resistance in international studies.

Table 3.

Observed clopidogrel resistance in Indian studies.

With this background, we conducted the present study to determine the extent of resistance to clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor in a real life set of patients with coronary artery disease.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study population and design

This is a prospective, comparative, observational single-center cohort study, which included 539 consecutive patients who underwent a PCI at Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and Medical Research Institute, Mumbai. The institutional review board of the hospital approved the study protocol.

Patients were eligible if they were ≥18 years of age and had confirmed CAD and underwent PCI. The exclusion criteria were known allergy to clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor; a platelet count less than 100 × 109/L or greater than 500 × 109/L; any active bleeding or history of gastrointestinal bleeding within the previous 2 months; any other major surgical procedure within 2 weeks prior to the study; and pregnancy. All patients who underwent PCI and were considered for the study were on aspirin and on any of the three drugs, namely, clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor and were followed up regularly in the outpatient department.

In all patients, response to the treatment was assessed using thrombelastography or TEG® 24 h after initiation of the second antiplatelet medication. The percentage platelet inhibition was assessed along with the resistance and sensitivity to the drug. Patients resistant to clopidogrel were shifted to either prasugrel or ticagrelor, while patients resistant to prasugrel were switched to ticagrelor and then the percent platelet inhibition was reassessed again after 24–48 h. The patients who were resistant to ticagrelor were continued on the same and rechecked after 24 h.

3.2. Blood sampling

Each blood sample required collection of 10 ml of blood into Vacutainer tubes (BD Medical Systems) containing EDTA, sodium citrate (3.2%), and heparin (in separate tubes).

3.3. Thrombelastography parameters measured

Thrombelastography or TEG® was used to measure the percentage of platelet inhibition by aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor. The TEG parameters recorded in the present study include:

-

1.

Reaction time (R), the time required from the start of blood sample test to fibrin formation; normal range is 2–8 min; >8 min is enzymatic hypocoagulability, and <2 min is enzymatic hypercoagulability.

-

2.

Maximum amplitude (MA): the MA of platelet function; normal is 51–69 mm, <51 mm denotes hypocoagulability; >69 mm denotes hypercoagulability.

As MA, which represents the maximal clot strength, can be ascertained by the binding of activated platelets to a fibrin mesh, 360 μl of heparinized blood was added to 10 μl of Activator F (Reptilase and Factor XIIIa) in channel 1. Thus, the contribution of each fibrin meshwork to clot strength (MAFibrin) was assessed in channel 1. In channels 2 and 3, 360 μl of heparinized blood was added to 10 μl of ADP (final concentration 2 μM) and 10 μl of arachidonic acid (AA; final concentration 1 mM), respectively along with 10 ml of Activator F. Channels 2 (MAADP) and 3 (MAAA) help calculate the contribution of platelets, as activated by ADP or AA, respectively, to clot strength. Maximal clot strength with maximally stimulated platelets (MAThrombin) was assessed in channel 4 by adding 360 μl of Kaolin-activated citrated blood to calcium chloride 0.2 M, 20 μl.

Percentage platelet inhibition is defined by the extent of nonresponse of the platelet ADP or TXA2 receptor to the exogenous ADP and AA as measured by TEG MA. The percentage platelet aggregation to agonist can be calculated by: [(MAADP/AA − MAFibrin)/(MAThrombin − MAFibrin) × 100]. This calculation is performed by the TEG-PM software. Thus, the percentage platelet inhibition due to clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor was calculated.

3.4. Definition of outcomes

The percentage of patients sensitive and resistant to and the average percentage platelet inhibition with the ADP receptor antagonists, namely clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor, were recorded and were considered as the primary outcome of the study. The average platelet inhibition was analyzed in both the resistant and sensitive groups for each of the ADP receptor antagonists. Sensitivity and resistance to the specific drug was defined as >50% and <50% of mean platelet inhibition, respectively.

The effect of other variables, including age (>60 years and <60 years), creatinine values (<1 mg/dL and >1 mg/dL), weight (>60 kg and <60 kg), hypertension, and diabetes on the sensitivity and resistance to oral antiplatelet therapy with ADP receptor antagonists, were recorded as secondary outcomes.

In addition, the efficacy of prasugrel on clopidogrel nonresponders and of ticagrelor on clopidogrel and prasugrel nonresponders was also evaluated as the secondary outcome.

3.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R (open source statistical software) and Excel statistics software package. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square (χ2) test while continuous variables were compared between multiple groups using independent sample t tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Study population

A total of 539 patients were enrolled in this study. The mean age of patients in the study population was 59.12 years and the mean weight was 73.3 kg. All 539 patients were treated with aspirin, 241 were tested for clopidogrel, 156 for prasugrel and 235 for ticagrelor.

Additionally those resistant to either clopidogrel or prasugrel were shifted to another drug and retested.

4.2. Effects of clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor on platelet inhibition

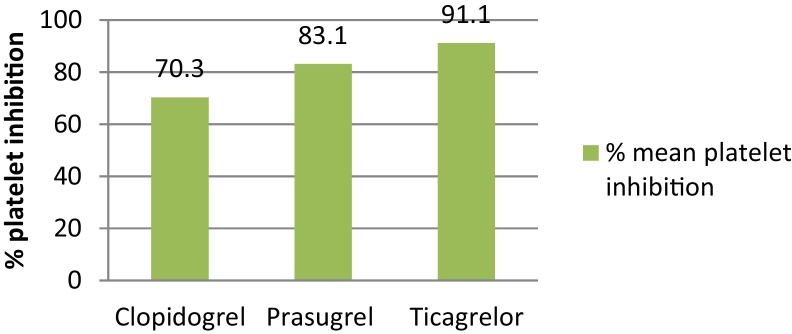

The study found that the mean percentage platelet inhibition was significantly higher in patients with ticagrelor as compared with clopidogrel and with prasugrel (p value of 0.0001 and 0.0043, respectively). In addition, the average percent platelet inhibition in patients treated with clopidogrel was significantly lesser as compared with those treated with prasugrel with a p value of 0.0001, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Average percent platelet inhibition with three different drugs studied. The average % platelet inhibition with ticagrelor was statistically significant within the group with a p value of 0.001 by applying ANOVA.

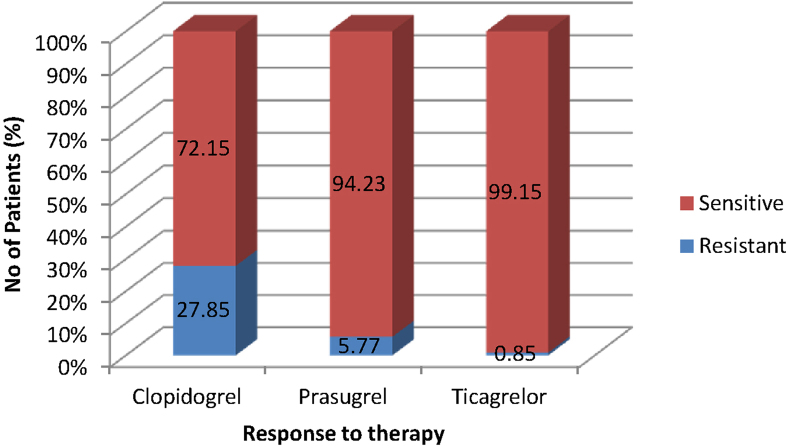

4.3. Response to treatment

As shown in Fig. 3, about 99.15% of the patients treated with ticagrelor were sensitive to the drug and the difference between the groups for sensitivity was significant (p value of 0.00001) in favor of ticagrelor. It was also found that ticagrelor was significantly (p value of 0.001) associated with the least resistance as compared with the other drugs in the group.

Fig. 3.

Response to antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. Percentage of patients sensitive to ticagrelor was statistically significant within the group with a p value of 0.00001333 by chi-square.

4.4. Effects of secondary parameters on the response to treatment

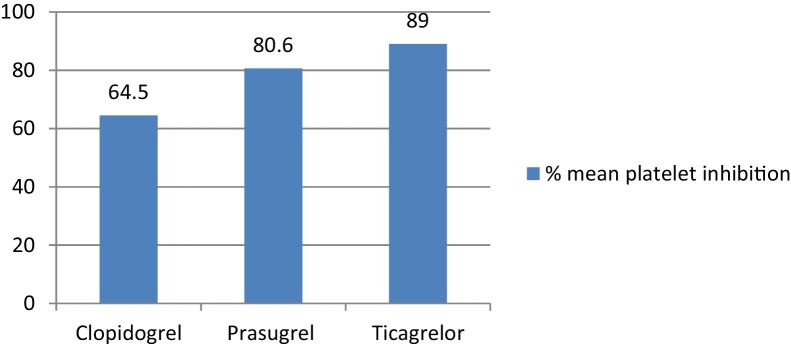

The number of patients sensitive and resistant to oral antiplatelet therapy with the ADP receptor antagonists clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor in each of the subgroups, including age (>60 years and <60 years), creatinine values (<1 mg/dL and >1 mg/dL), weight (>60 kg and <60 kg), hypertension, and diabetes, are highlighted in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7.

Fig. 4.

Mean % platelet inhibition in >60 years of age group. Clopidogrel vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.0001; clopidogrel vs. ticagrelor, p value = 0.00001; ticagrelor vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.0022.

Fig. 5.

Mean % platelet inhibition in <60 kg of weight group. Clopidogrel vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.00001; clopidogrel vs. ticagrelor, p value = 0.00001; ticagrelor vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.0002.

Fig. 6.

Mean % platelet inhibition in patients with creatinine values of >1 mg/dL. Clopidogrel vs. prasugrel, p value = 0 .00001; clopidogrel vs. ticagrelor, p value = 0.00001; ticagrelor vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.0036.

Fig. 7.

Mean % platelet inhibition in patients with hypertension. Clopidogrel vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.00001; clopidogrel vs. ticagrelor, p value = 0.00001; ticagrelor vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.0139.

4.5. Impact of age and weight on the response to treatment

Ticagrelor was associated with significantly higher mean percentage platelet inhibition in the group >60 years and in the group <60 kg of weight as compared with clopidogrel and prasugrel (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). This suggested that age and weight were not a factor in the superior response of ticagrelor over clopidogrel or prasugrel.

4.6. Impact of creatinine level on the response to treatment

In patients with creatinine levels of >1 mg/dL, significantly more patients were sensitive; and significantly, fewer patients were resistant in the ticagrelor group as compared with clopidogrel with the p value of 0.0005. Ticagrelor was associated with significantly higher mean percentage platelet inhibition in the group of patients with creatinine values of >1 mg/dL as compared with clopidogrel and prasugrel (Fig. 6).

4.7. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors on the response to treatment

4.7.1. Hypertension

About 98.6% of patients were sensitive in the ticagrelor group as compared with 70.3% to clopidogrel (p = 0.001) and 93.5% to prasugrel (p = 0.01). Ticagrelor was associated with the least percentage of resistant patients (1.4%) as compared with prasugrel (6.5%; p = 0.01) and clopidogrel (29.7%; p = 0.001). The difference between clopidogrel and prasugrel was also significant (p < 0.00001).

Ticagrelor was associated with significantly higher mean percentage platelet inhibition in patients with hypertension as compared with clopidogrel and prasugrel (Fig. 7).

4.7.2. Diabetes

In the diabetic subgroup, a total of 98.8% patients were sensitive in the ticagrelor group as compared with 70.4% in the clopidogrel (p = 0.001) and 91.4% in the prasugrel (p = 0.08) groups. Ticagrelor was associated with the least percentage of resistant patients (1.2%) as compared with prasugrel (8.6%; p = 0.08) and clopidogrel (29.6%; p = 0.001).

Ticagrelor was associated with significantly higher mean percentage platelet inhibition in patients with diabetes as compared with clopidogrel. While the mean percentage platelet inhibition with ticagrelor was also higher than that with prasugrel, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Mean % platelet inhibition in patients with diabetes. Clopidogrel vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.00001; clopidogrel vs. ticagrelor, p value = 0.00001; ticagrelor vs. prasugrel, p value = 0.6642.

4.8. Effect of ticagrelor in patients resistant to clopidogrel and prasugrel

A total of 9 patients resistant to clopidogrel were shifted to ticagrelor loading and maintenance dose. All these patients became sensitive to ticagrelor with the mean percent platelet inhibition of 90%. The mean percent platelet inhibition increased from 14.87% to 90% in these patients after switching.

In addition, 2 patients resistant to prasugrel who were shifted to ticagrelor became sensitive to ticagrelor with the mean percent platelet inhibition of 90%. Among 52 patients resistant to clopidogrel and who were switched to prasugrel, 50 patients became sensitive and 2 were resistant to prasugrel treatment with the mean platelet inhibition rate of 86% and 44%, respectively.

A total of 2 patients who were resistant to ticagrelor continued with the same treatment and became sensitive after a further 24 h of continued treatment with ticagrelor.

4.9. Safety

No fatal reaction to any antiplatelet drug was recorded. One patient on clopidogrel and three patients on prasugrel had gastrointestinal bleeding that required blood transfusion. No serious bleeding requiring blood transfusion was recorded with ticagrelor. Three patients on ticagrelor had to be switched to prasugrel due to dyspnea. Minor bleeding, such as dental bleeds or nosebleeds, was recorded with all drugs, but these required no treatment or change of therapy. Skin bruising was reported with all antiplatelet agents but it did not necessitate change in therapy. No bradycardia was reported or recorded with patients on ticagrelor.

5. Discussion

The results of this observational study, which evaluated the percentage of platelet inhibition with ticagrelor, clopidogrel, or prasugrel, as dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin in patients who underwent PCI, demonstrated that ticagrelor therapy was associated with a statistically significant higher mean percentage platelet inhibition (89.9%) as compared with clopidogrel (67.4%) and prasugrel (85.2%). The study also demonstrated ticagrelor sensitivity in 99.15% of the patients, which was statistically significantly higher than prasugrel sensitivity in 94.23% of the patients, and clopidogrel sensitivity in 72.15% of the patients.

All current guidelines including the latest 2014 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) guidelines on myocardial revascularization recommend P2Y12 inhibitors (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel) as dual antiplatelet therapy along with aspirin, in patients undergoing PCI.26

Although clopidogrel is recommended in these patients, the irreversibility and disparity of platelet inhibition with clopidogrel has led to dispute about its optimum dose and timing of administration in patients undergoing PCI.26, 27, 28, 29

Ticagrelor is observed to reach IPA of 80–90% approximately in 2–4 h after a 180 mg loading dose,28, 29 which is consistent with the current study finding of a mean platelet inhibition of 89.9% in 24 h with 180 mg loading and 90 mg twice daily maintenance dose of ticagrelor. Moreover, mean platelet inhibition of 67.4% achieved with 300 mg loading and 75 mg daily maintenance of clopidogrel within 24 h is comparable with other studies, which reported a 30–50% platelet inhibition with 300 mg and 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel in 4–8 h.28, 29

As discussed earlier, the PLATO trial demonstrated that ticagrelor significantly reduced the mortality rate due to vascular events, myocardial infarction, and stroke, as compared with clopidogrel, without an increase in the rate of major bleeding.30 More interesting is the fact that a substudy of the PLATO trial demonstrated that ticagrelor is associated with increased and more reliable platelet inhibition than clopidogrel,31 which is again consistent with the findings of this study.

Prasugrel is also an irreversible platelet inhibitor with the pharmacological effects based on its conversion to an active metabolite. However, unlike clopidogrel, the onset of action is faster (<30 min with 60 mg loading dose).32 Despite its rapid action, it is associated with increased risk of bleeding, as demonstrated in the TRITON-TIMI 38 study.33 Prasugrel resistance has not been described reliably and few studies so far have reported resistance. Our study, probably one of the few ones to do so, has demonstrated resistance to prasugrel in 5.77% of patients.

In 2012, Alexopoulos et al. reported that ticagrelor provided stronger platelet inhibition than prasugrel using the VerifyNow assay, attributing this to the nonhepatic mode of action of ticagrelor. Although prasugrel is not influenced by CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 polymorphism, it may be influenced by other abnormalities within the liver including other polymorphisms.34

5.1. Impact of clinical factors on the response to treatment with ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel

The current study also demonstrated that the antiplatelet effect of ticagrelor was not influenced by any of the clinical factors studied including age, weight, creatinine level, hypertension, and diabetes. In fact, ticagrelor achieved statistically significantly higher mean platelet inhibition in all these subgroups as compared with clopidogrel and prasugrel except in patients with diabetes, where the difference between ticagrelor and prasugrel was not significant but the difference between ticagrelor and clopidogrel was significant.

A substudy of the PLATO trials demonstrated that in patients with CKD, compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor was associated with a 23% reduction in the relative risk of the primary ischemic endpoint (when compared with a nonsignificant 10% decrease in patients without CKD) and was associated with even more striking reductions of 4.0% and 28%, respectively, in the absolute and relative risks of all-cause mortality.35 Also, Alexopoulos et al. reported prasugrel resistance in 19% of patients with CKD and on hemodialysis.34

In this scenario, the findings from our study may have significant clinical implications towards the use of ticagrelor in these subsets of patients.

As patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) have high platelet reactivity and are at an increased risk of ischemic events, a post hoc analysis of PLATO trial was conducted to study the effect of ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in patients with DM. The study found that ticagrelor was associated with the reduction in the primary composite endpoint (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.76–1.03), all-cause mortality (HR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.66–1.01), and stent thrombosis (HR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.36–1.17), with no increase in major bleeding (HR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.81–1.12) in patients with diabetes, as observed in the broad population of patients with ACS in the PLATO trial.36 In another study, Alexopoulos et al. directly compared the platelet inhibition with ticagrelor vs. that with prasugrel in patients with DM and ACS who had been pretreated with clopidogrel and underwent PCI. They demonstrated that ticagrelor achieved significantly higher platelet inhibition than prasugrel in these patients.37

Our study results indicate a similar benefit in these patients.

5.2. Efficacy of ticagrelor in clopidogrel nonresponders

In our study, ticagrelor therapy overwhelmed nonresponsiveness to clopidogrel (14.87%) with the mean percent platelet inhibition of 90% in these patients after switching over to ticagrelor. Similar to our study, The Response to Ticagrelor in Clopidogrel Nonresponders and Responders and Effect of Switching Therapies (RESPOND) study, a substudy of the PLATO trial, demonstrated that the IPA was higher in clopidogrel nonresponders treated with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel (p < 0.05). The IPA increased from 35 ± 11% to 59 ± 9% in patients switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor (p < 0.0001) and reduced from 56 ± 9% to 36 ± 14% in patients switched from ticagrelor to clopidogrel (p < 0.0001).38

5.3. Limitations of the study

While the results of this study are of significant importance, it has few limitations, the major one being its nonrandomised and observational design. Moreover results may be considered as indicative. However, we were able to capture a real life set of patient population that is similar to that observed in other studies of the same design. The baseline variables were similar and any confounding variables are unlikely to have had any effect on the results.

We also compared using only serum creatinine values, whereas creatinine clearance would have provided better information.

Also only one test (TEG) was used to evaluate the mean percentage platelet inhibition that was available in our hospital 24/7. Platelet inhibition testing in vitro has its limitations for predicting clinical events and TEG also suffers from the same limitation, though some data of association with clinical events have been published. We changed patients resistant to prasugrel to ticagrelor because it was a newer molecule that had just been introduced. We do not have any information if clopidogrel had been used in these patients and that decision remains with the treating physician. Finally, we did not collect pharmacokinetic samples for the analysis of clopidogrel or prasugrel metabolites or serum levels of ticagrelor. Hence, it is beyond the scope of this study to comment on the pharmacokinetic correlation with the observed effects of the study drugs.

6. Conclusion

In patients with CAD undergoing PCI, the use of ticagrelor as dual therapy along with aspirin was associated with a significantly higher mean percentage platelet inhibition, higher sensitivity, and lower resistance, as compared with clopidogrel and prasugrel. This was seen even in patients resistant to either of the two drugs.

Conflicts of interest

The first two authors have none to declare and the third author is associated with Astra.

References

- 1.Jha P., Gajalakshmi V., Gupta P.C. Prospective study of one million deaths in India: rationale, design, and validation results. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta R., Guptha S., Sharma K.K. Regional variations in cardiovascular risk factors in India: India heart watch. World J Cardiol. 2012;4:112–120. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v4.i4.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kottke-Marchant K. Importance of platelets and platelet response in acute coronary syndromes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(suppl 1):S2–S7. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s1.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gachet C., Aleil B. Testing antiplatelet therapy. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2008;10(suppl):A28–A34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thakur M., Ahmed A.B. A review of thromboelastography. IJPUT. 2012;1:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wijeyeratne Y.D., Heptinstall S. Anti-platelet therapy: ADP receptor antagonists. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:647–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallentin L. P2Y12 inhibitors: differences in properties and mechanisms of action and potential consequences for clinical use. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1964–1977. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonello L., Pansieri M., Mancini J. High on-treatment platelet reactivity after prasugrel loading dose and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silvano M., Zambon C.F., De Rosa G. A case of resistance to clopidogrel and prasugrel after percutaneous coronary angioplasty. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;31:233–234. doi: 10.1007/s11239-010-0533-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morel O., Muller C., Jesel L. Impaired platelet P2Y12 inhibition by thienopyridines in chronic kidney disease: mechanisms, clinical relevance and pharmacological options. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1994–2002. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawarskas J.J., Snowden S.S. Critical appraisal of ticagrelor in the management of acute coronary syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:473–488. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S19835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiviott S.D., Antman E.M. Clopidogrel resistance: a new chapter in a fast-moving story. Circulation. 2004;109:3064–3067. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134701.40946.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasparyan A.Y. Aspirin and clopidogrel resistance: methodological challenges and opportunities. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:109–112. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guha S., Sardar P., Guha P. Dual antiplatelet drug resistance in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Indian Heart J. 2009;61:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaremo P., Lindahl T.L., Fransson S.G. Individual variations of platelet inhibition after loading doses of clopidogrel. J Intern Med. 2002;252:233–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurbel P.A., Bliden K.P., Hiatt B.L. Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation. 2003;107:2908–2913. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072771.11429.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller I., Besta F., Schulz C. Prevalence of clopidogrel non-responders among patients with stable angina pectoris scheduled for elective coronary stent placement. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:783–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mobley J.E., Bresee S.J., Wortham D.C. Frequency of nonresponse antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel during pretreatment for cardiac catheterization. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:456–458. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lepantalo A., Virtanen K.S., Heikkila J. Limited early antiplatelet effect of 300 mg clopidogrel in patients with aspirin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angiolillo D.J., Fernandez-Ortiz A., Bernardo E. Identification of low responders to a 300-mg clopidogrel loading dose in patients undergoing coronary stenting. Thromb Res. 2005;115:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matetzky S., Shenkman B., Guetta V. Clopidogrel resistance is associated with increased risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:3171–3175. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130846.46168.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dziewierz A., Dudek D., Heba G. Inter-individual variability in response to clopidogrel in patients with coronary artery disease. Kardiol Pol. 2005;62:108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lev E.I., Patel R.T., Maresh K.J. Aspirin and clopidogrel drug response in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the role of dual drug resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kar R., Meena A., Yadav B.K. Clopidogrel resistance in North Indian patients of coronary artery disease and lack of its association with platelet ADP receptors P2Y1 and P2Y12 gene polymorphisms. Platelets. 2013;24:297–302. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.693992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S., Saran R.K., Puri A. Profile and prevalence of clopidogrel resistance in patients of acute coronary syndrome. Indian Heart J. 2007;59:152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/ehj/early/2014/09/10/eurheartj.ehu278.full.pdf. Accessed 30.12.14.

- 27.Plavix®(clopidogrel bisulfate) tablets [prescribing information] Bridgewater, NJ. Sanofi Aventis. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/020839s058lbl.pdf.

- 28.Gurbel P.A., Bliden K.P., Butler K. Randomized double-blind assessment of the ONSET and OFFSET of the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with stable coronary artery disease: the ONSET/OFFSET study. Circulation. 2009;120:2577–2585. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.912550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storey R.F., Husted S., Harrington R.A. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by AZD6140, a reversible oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1852–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallentin L., Becker R.C., Budaj A. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storey R.F., Angiolillo D.J., Patil S.B. Inhibitory effects of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel on platelet function in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Effient®(prasugrel) tablets [prescribing information] Indianapolis, IN. Eli Lilly and Company. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022307s000lbl.pdf.

- 33.Wiviott S.D., Braunwald E., McCabe C.H. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexopoulos D., Panagiotou A., Xanthopoulou I. Antiplatelet effects of prasugrel vs. double clopidogrel in patients on hemodialysis and with high on-treatment platelet reactivity. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2379–2385. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James S., Budaj A., Aylward P. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromes in relation to renal function: results from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation. 2010;122:1056–1067. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James S., Angiolillo D.J., Cornel J.H. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and diabetes: a substudy from the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:3006–3016. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexopoulos D., Xanthopoulou I., Mavronasiou E. Randomized assessment of ticagrelor versus prasugrel antiplatelet effects in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2211–2216. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurbel P.A., Bliden K.P., Butler K. Response to ticagrelor in clopidogrel nonresponders and responders and effect of switching therapies: the RESPOND study. Circulation. 2010;121:1188–1199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.919456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]