Abstract

Diuretics have long been cherished as drugs of choice for uncomplicated primary hypertension. Robust mortality and morbidity data is available for diuretics to back this strategy. Off-late the interest for diuretics has waned off perhaps due to availability of more effective drugs but more likely due to perceived lack of tolerance and side-effect profile of high-dose of diuretics required for mortality benefit. Low-dose diuretics particularly thiazide diuretics are safer but lack the mortality benefit shown by high-dose. However, indapamide and low dose chlorthalidone have fewer side-effects but continue to provide mortality benefit.

Keywords: Diuretics, Hydrochlorothiazide, Chlorthalidone, Indapamide, Mortality, Cardiovascular outcome

1. Introduction

Diuretics, particularly thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics have been the gold standard of antihypertensive therapy for uncomplicated primary hypertension (formerly known as essential hypertension) till recent past. Several trials, even some relatively recent ones have demonstrated mortality benefit with diuretic therapy in uncomplicated hypertension.1, 2, 3 Several JNC Guidelines have kept diuretics as first-line agent (even drug of choice) in management of uncomplicated hypertension.4, 5 No individual can be labeled as resistant hypertension unless a concurrent use of 3 antihypertensive agents of different classes, one of the 3 agents a diuretic, prescribed at optimal dose has been instituted.6 However, despite robust clinical data, their use in real-world practice has continued to decline.7 This is rather intriguing and may be related to several misconceptions prevailing about use of diuretics in primary hypertension: (1) the use of diuretics does not result in decrease in morbidity or mortality; (2) diuretics are poorly tolerated; and (3) use of diuretics is associated with significant adverse metabolic effects (increased lipid levels, adverse effects on glucose metabolism, effects on arrhythmias, etc.).8, 9, 10 The efforts to promote newer medications may feed on these misconceptions.11, 12, 13, 14 However, the incidence and magnitude of these side effects are much lower with low-dose therapy (12.5–25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide or chlorthalidone) but one cannot assume that the benefits of high dose thiazides would have replicated with lower doses of hydrochlorothiazide as commonly used in the treatment of primary hypertension. Herein rests the role of indapamide or low dose chlorthalidone.

2. Mortality reduction

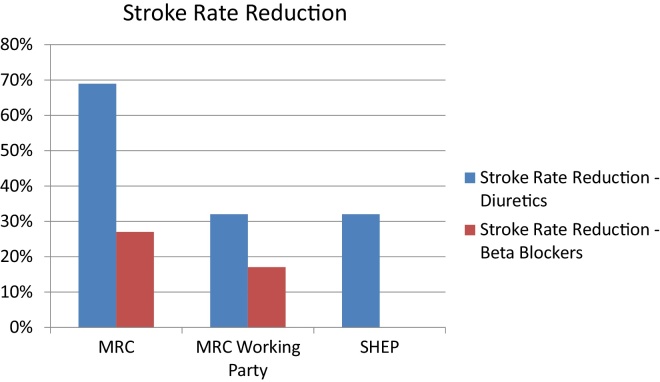

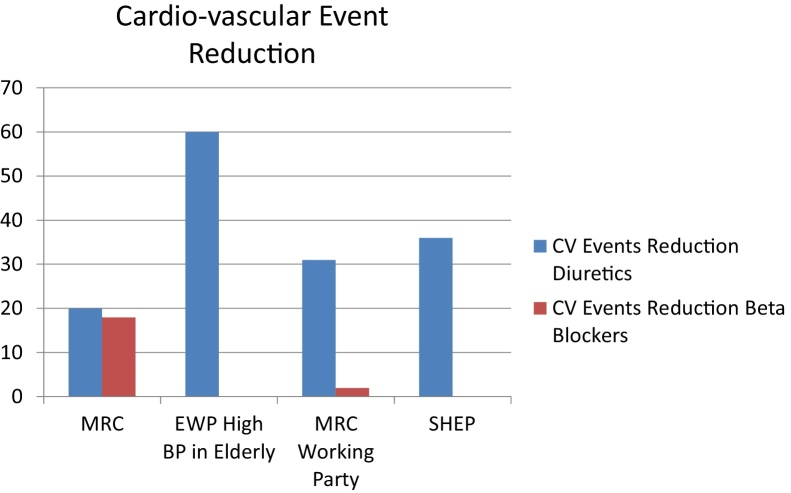

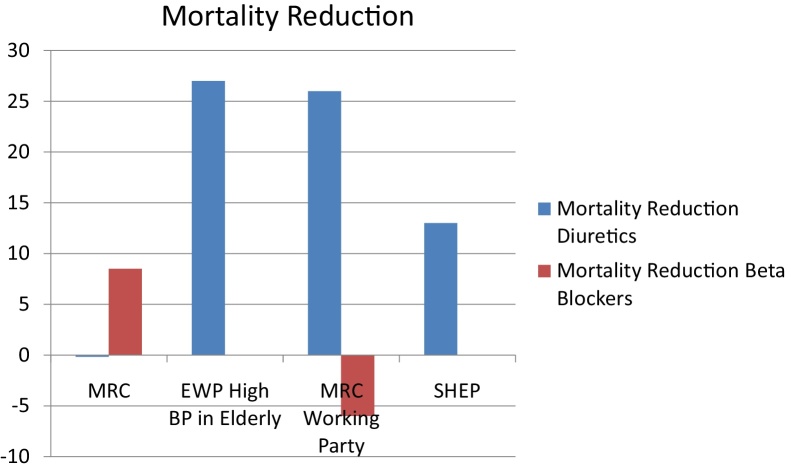

The early landmark trials for treatment of hypertension demonstrated significant reduction of stroke, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with BP lowering, primarily with thiazide diuretics (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).15, 16, 17, 18 Relatively recently, head-to-head comparison between various anti-hypertensive agents, in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), chlorthalidone was found superior in preventing one or more major forms of CV disease.3 A subsequent meta-analysis also revealed a superiority of thiazide type diuretics over other anti-hypertensive agents in terms of various adverse CV outcome reductions.19 A recent meta-analysis involving 12 RCTs (48 898 patients) revealed a reduction in relative risk for stroke (37%), heart failure (49%), CAD (18%), cardiovascular death (18%) and all-cause death (1%), all statistically significant. Nine other studies including secondary analysis (66 788 patients) in which diuretics were used in association with other drugs, risk reduction with diuretics was similar.20 In this study, use of diuretics prevented 15 strokes, 24 major cardiovascular events and eight deaths every 1000 patients treated for 5 years (with NNT of 67, 41 and 118, respectively). Not only uncomplicated primary hypertension, there is numerous evidence to support the use of diuretics (over other anti-hypertensives) in several patient populations, so much so that the use of diuretics features in many treatment guidelines.21, 22, 23

Fig. 1.

Stroke rate reduction with diuretics.

Fig. 2.

Cardiovascular risk reduction with diuretics.

Fig. 3.

Mortality reduction with diuretics.

3. Concerns with diuretic therapy

Lack of tolerability of diuretics has been a major concern limiting their use. Available studies reveal that diuretics either do not interfere with, or may actually improve, quality of life in hypertensive patients. Particularly, low-dose diuretic treatment is a well-tolerated and may be an excellent initial choice for hypertensive patients, even elderly. However, high-dose diuretics should be avoided, in patients with co-morbidities like diabetes, gout, or erectile dysfunction in men.24 The potential adverse metabolic effects of thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics include abnormalities in carbohydrate, electrolyte, uric acid and lipid metabolism.25, 26 Again these side-effects are more common with high dose therapy. Use of high dose diuretic without a potassium-sparing agent has been even associated with sudden cardiac death.27

4. Low dose diuretic therapy

To reduce the side-effects of high-dose thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics, they are typically used at low doses (12.5–25 mg/day of chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide, or 1.5 mg of indapamide SR) which minimizes the metabolic complications, while maintaining the antihypertensive response.26, 28, 29 Among the three anti-hypertensive agents, low doses of chlorthalidone and indapamide were more effective in lowering blood pressure than hydrochlorothiazide but metabolic abnormalities (although lower than high dose) were greater with low doses chlorthalidone than with hydrochlorothiazide or indapamide.29 Thus on balance of things it appears that indapamide is both effective and safer at low doses compared with other diuretics. Even though in ALLHAT Trial low dose chlorthalidone was associated with a plasma potassium reduction of only 0.2 meq/L, 8.5% patients required potassium supplements and a significantly higher number of non-diabetic patients at baseline developing elevation of fasting blood glucose level to values ≥126 mg/dL compared with amlodipine and lisinopril (11.6% vs. 9.8% {p = 0.04} and 8.1% {p < 0.001}, respectively).1 Persistent activation of sympathetic nervous system and insulin resistance could be the reason for increased new onset of diabetes with chlorthalidone.30

5. Limitations of low dose diuretic therapy

An interesting point is that although low dose thiazide/thiazide like diuretic therapy minimizes the metabolic complications, it may not eliminate other side effects; 25% of men treated with 25 mg of chlorthalidone per day develop a decline in sexual function and sleep disturbances may also occur, particularly if the patient is also on a low-sodium diet.31 Further, in a meta-analysis where 8 trials classified as low dose were compared with 4 trials of high dose diuretics, stroke rate reduction was much higher with high-dose and total cardiovascular risk was much lower in high-dose than in low-dose diuretic trials (cardiovascular death 4.8%, rather than 17.6% in 10 years).20

6. Are all diuretics equal?

In the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT) study, while high-dose hydrochlorothiazide was found to be equal to calcium antagonists at doses below 25 mg, there was no evidence of reduction in morbidity and mortality.32 Chlorthalidone is 1.5–2 times as potent as hydrochlorothiazide and has shown significant CV events reduction vs. both hydrochlorothiazide and placebo.33, 18, 34 However, in the largest hypertension trial ALLHAT, low dose Chlorthalidone (12.5–25 mg daily) was found superior to other anti-hypertensive agents although metabolic side effects did occur.3 On the other hand indapamide, a thiazide like diuretic whether used alone or in combination has not only shown a consistent blood pressure lowering response but also improvement in cardio-vascular outcomes. As a matter of fact, the HYVET study had to be prematurely stopped due to a phenomenal 21% reduction in all-cause mortality in patients receiving indapamide.35 Further, there was also a 39% reduction in fatal strokes & a 64% reduction in heart failure. Long-term (1-year extension) provided an even better reduction of 52% in all-cause mortality.36 In the PROGRESS trial, indapamide in combination with perindopril reduced stroke by 43%.37 In the ADVANCE trial in diabetic patients, a combination of indapamide and perindopril reduced all-cause mortality by 14%, CV mortality by 18% and renal events by 21%.38 It further provides proof of metabolic safety of indapamide on long-term basis; hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) being maintained over nearly 5 year period. In PATS, indapamide showed a significant reduction in secondary strokes by 29%.39 However, it is important to note that these benefits of indapamide are evident even at the therapeutic dosage of either 2.5 mg immediate release or the superior 1.5 mg sustained release. One of the reasons for the salutatory effects of indapamide4 could be its predominantly vascular effect. This minimizes the risk of diuretic related side effects like electrolytic or metabolic disturbances. In a meta-analysis by Thomopoulos et al. a separate analyses were done according to the type of diuretic used as low-dose diuretic. Low dose thiazides were found useful in reducing only composite end-points (stroke and CAD and stroke, CAD, heart failure, and cardiovascular death) but no individual end-points. Chlorthalidone, on the other hand reduced stroke, CAD, heart failure and their composites but not cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.20 It was only low-dose indapamide which caused significant risk reduction in all components; stroke, composite of stroke and CHD, and all-cause death.20 Another meta-analysis of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring trials revealed that there was no evidence of reduction in even combined CV outcomes (heart attacks, stroke, death) with low doses of hydrochlorothiazide (12.5–25 mg). Further, even the 24-h BP control (only 6.5/4.5 mmHg) was found much inferior to other antihypertensive classes.40

7. Conclusions

Diuretics have remained first line therapy in management of uncomplicated primary hypertension since last several decades. They are perhaps the only anti-hypertensive agents that have demonstrated a robust and a consistent reduction not only in blood pressure but also in cardio-vascular outcomes. Despite impressive clinical data their use has been declining in recent years. This may be related to concerns about tolerability and effect on metabolic profile at least by high-dose diuretics. Lower-dose diuretics decrease side-effects but their action on cardio-vascular outcomes also decreases. Lower dose hydrochlorothiazide is a weak anti-hypertensive and does not seem to reduce cardio-vascular outcomes. Low dose chlorthalidone is effective and also reduces some cardiovascular outcomes but metabolic side-effects though reduced, still persist. It is only low dose indapamide which is not only effective but also consistently reduces cardiovascular outcomes including all-cause mortality. In this context it is intriguing that low dose diuretics particularly indapamide are still underutilized.

If you ever get close to a human and human behavior

Be ready, be ready to get confused and me and my here after

There's definitely, definitely, definitely no logic to human behavior

References

- 1.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright J.T., Jr., Probstfield J.L., Cushman W.C. ALLHAT findings revisited in the context of subsequent analyses, other trials, and meta-analyses. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:832. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 2000;283:1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI) Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden L.G., He J., Lydick E., Whelton P.K. Long-term absolute benefit of lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients according to the JNC VI risk stratification. Hypertension. 2000;35(2):539–543. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calhoun D.A., Jones D., Textor S. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2008;51:1403–1419. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manolio T.A., Cutler J.A., Furbert C.D. Trends in pharmacologic management of hypertension in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1995;165:829–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moser M. Why are physicians not prescribing diuretics more frequently in the management of hypertension? JAMA. 1998;279:1813–1816. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middeke M., Weisweiler P., Schwandt P. Serum lipoprotein during antihypertensive therapy with beta blockers and diuretics: a controlled long-term comparative trial. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:94–98. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messerli F.H., Nunez B.D., Nunez N.M. Hypertension and sudden death: disparate effects of calcium entry blockers and diuretic therapy on cardiac dysrhythmias. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1263–1267. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.6.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moser M. Current hypertension management: separating fact from fiction. Cleveland Clin J Med. 1993;60:27–37. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.60.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moser M. Suppositions and speculations—their possible effects on treatment decisions in the management of hypertension. Am Heart J. 1989;118:1362–1369. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houston N.C. New insights and new approaches for the treatment of essential hypertension: selection of therapy based on coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factor analysis, hemodynamic profiles, quality of life, and subsets of hypertension. Am Heart J. 1989;117:911–949. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90631-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser M., Blaufox M.D., Freis E. Who really determines your patients’ prescriptions? JAMA. 1991;265:498–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Medical Research Council Working Party. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291(6488):97–104. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6488.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amery A., Birkenhäger W., Brixko P. Mortality and morbidity results from the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly trial. Lancet. 1985;1(8442):1349–1354. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MRC Working Party Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ. 1992;304(6824):405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SHEP Cooperative Research Group Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) JAMA. 1991;265(24):3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psaty B.M., Lumley T., Furberg C.D. Health outcomes associated with various antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a network meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2534–2544. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomopoulos C., Parati G., Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 4. Effects of various classes of antihypertensive drugs – overview and meta-analyses. J Hypertens. 2015;33(2):195–211. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chobanian A.V., Bakris G.L., Black H.R. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancia G., De Backer G., Dominiczak A. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2007;28(12):1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosendorff C., Black H.R., Cannon C.P. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2007;115(21):2761–2788. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.183885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weir M.R., Flack J.M., Applegate W.B. Tolerability, safety, and quality of life and hypertensive therapy: the case for low-dose diuretics. Am J Med. 1996;101(3A):83S–92S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung A.A., Wright A., Pazo V. Risk of thiazide-induced hyponatremia in patients with hypertension. Am J Med. 2011;124:1064. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlsen J.E., Køber L., Torp-Pedersen C., Johansen P. Relation between dose of bendrofluazide, antihypertensive effect, and adverse biochemical effects. BMJ. 1990;300:975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6730.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siscovick D.S., Raghunathan T.E., Psaty B.M. Diuretic therapy for hypertension and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Materson B.J., Cushman W.C., Goldstein G. Treatment of hypertension in the elderly. I. Blood pressure and clinical changes. Results of a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Hypertension. 1990;15:348. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musini V.M., Nazer M., Bassett K., Wright J.M. Blood pressure-lowering efficacy of monotherapy with thiazide diuretics for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003824. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003824.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menon D.V., Arbique D., Wang Z. Differential effects of chlorthalidone versus spironolactone on muscle sympathetic nerve activity in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1361–1366. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wassertheil-Smoller S., Blaufox M.D., Oberman A. Effect of antihypertensives on sexual function and quality of life: the TAIM Study. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:613. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-8-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown M.J., Palmer C.R., Castaigne A. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double-blind treatment with a long-acting calcium-channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT) Lancet. 2000;356(9227):366–372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortality after 10½ years for hypertensive participants in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Circulation. 1990;82(5):1616–1628. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group The effect of treatment on mortality in “mild” hypertension: results of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(16):976–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210143071603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HYVET Study Group, Beckett N.S., Peters R. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beckett N., Peters R., Tuomilehto J. Immediate and late benefits of treating very elderly people with hypertension: results from active treatment extension to hypertension in the very elderly randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;344:d7541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ADVANCE Collaborative Group, Patel A., MacMahon S. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):829–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PROGRESS Collaborative Group Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2001;358(9287):1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.PATS Collaborating Group Poststroke antihypertensive treatment study. A preliminary result. Chin Med J (Engl) 1995;108:710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Messerli F.H., Makani H., Benjo A. Antihypertensive efficacy of hydrochlorothiazide as evaluated by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(5):590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]