Abstract

Objective

To synthesize and critique the quantitative literature on measuring childbirth self-efficacy and the effect of childbirth self-efficacy on perinatal outcomes.

Data Sources

Eligible studies were identified through searching MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases.

Study Selection

Published research using a tool explicitly intended to measure childbirth self-efficacy and also examining outcomes within the perinatal period were included. All manuscripts were in English and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Data Extraction

First author, country, year of publication, reference and definition of childbirth self-efficacy, measurement of childbirth self-efficacy, sample recruitment and retention, sample characteristics, study design, interventions (with experimental and quasi-experimental studies), and perinatal outcomes were extracted and summarized.

Data Synthesis

Of 619 publications, 23 studies published between 1983 and 2015 met inclusion criteria and were critiqued and synthesized in this review.

Conclusions

There is overall consistency in how childbirth self-efficacy is defined and measured among studies, facilitating comparison and synthesis. Our findings suggest that increased childbirth self-efficacy is associated with a wide variety of improved perinatal outcomes. Moreover, there is evidence that childbirth self-efficacy is a psychosocial factor that can be modified through various efficacy-enhancing interventions. Future researchers will be able to build knowledge in this area through: (a) utilization of experimental and quasi-experimental design; (b) recruitment and retention of more diverse samples; (c) explicit reporting of definitions of terms (e.g. ‘high risk’); (d) investigation of interventions that increase childbirth self-efficacy during pregnancy; and, (e) investigation regarding how childbirth self-efficacy enhancing interventions might lead to decreased active labor pain and suffering. Exploratory research should continue to examine the potential association between higher prenatal childbirth self-efficacy and improved early parenting outcomes.

Keywords: Childbirth self-efficacy, literature review, perinatal outcomes

Multiple physiologic factors likely influence outcomes during the perinatal period, defined as obstetrics events from mid-pregnancy (i.e., 20 weeks gestation) through the first month postpartum (Gabbe, 2012). There is also evidence that a woman’s psychosocial status can affect perinatal outcomes. For example, increased stress during pregnancy is associated with higher rates of premature birth (Arck, 2010), grief during pregnancy is associated with stillbirth (Laszlo, 2013) and women with fear of childbirth more frequently have unplanned cesarean births (Sydsjo, Sydsjo, Gunnervik, Bladh, & Josefsson, 2012). However, there are inconsistencies in knowledge regarding enhancing a woman’s psychosocial status with the goal of improving perinatal outcomes (Gagnon & Sandall, 2007; Goldenberg, 2011; Kogan, 1998; Novick, 2004; Ruiz-Mirazo, Lopez-Yarto, & McDonald, 2012). Identifying modifiable psychosocial factors that positively affect perinatal outcomes is an important but poorly understood area of investigation. One psychosocial variable which holds promise for this purpose is self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy is a concept widely used to predict health behavior (Lenz, 2002) and was hypothesized to reduce fear (Bandura, 2004) and anxiety during the perinatal period (Khorsandi, 2008). Originally proposed by Bandura (1977), self-efficacy is defined as both the belief that one can successfully accomplish a task (i.e., efficacy expectancies) and one’s estimation that if the task is accomplished it will lead to specific outcomes (i.e., outcome expectancies). Self-efficacy is proposed to be situation, or domain, specific and to emerge from past performance accomplishments, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and emotional arousal (Bandura 1977).

Manning and Wright (1983) were the first to investigate self-efficacy in the context of childbirth; they observed that higher childbirth self-efficacy was associated with an increased capacity to cope with labor pain. Lowe (1993) later identified childbirth self-efficacy as the conceptual framework predicting confidence for coping with labor. Building upon these seminal studies, there has been an evolution of science on childbirth self-efficacy and perinatal outcomes that began with small descriptive work and has progressed to recent quasi-experimental and experimental designs. The purpose of our integrated review was to synthesize and critique the quantitative research literature and in so doing summarize the state of the science on childbirth self-efficacy and its effect on perinatal outcomes.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible studies for this review were selected using the following criteria: (1) childbirth self-efficacy was measured explicitly, (2) outcomes measured (e.g. labor pain scores, intention to attempt vaginal birth, parenting self-efficacy) fell within the perinatal period, (3) written in English, (4) published in a peer-reviewed journal, and (5) intended for outcomes research, not translation and psychometric testing.

Search Strategy

The first author searched for articles in MEDLINE and CINAHL data bases and used the MeSH terms or keywords self-efficacy’ and childbirth, or birth, orpregnancy/pregnan*, or labor, or labour,, or perinatal, or postpartum. After identification of all measures used to quantify childbirth self-efficacy, Scopus and Google Scholar databases were searched for publications referencing childbirth self-efficacy measures.

Data Selection

The first author screened titles and abstracts of all studies identified through the literature search. Abstracts suggesting that a publication likely met all inclusion criteria were compiled and the full text was reviewed. If abstract review left any uncertainty regarding whether a publication met criteria for inclusion, the full text of this publication was also reviewed.

Results

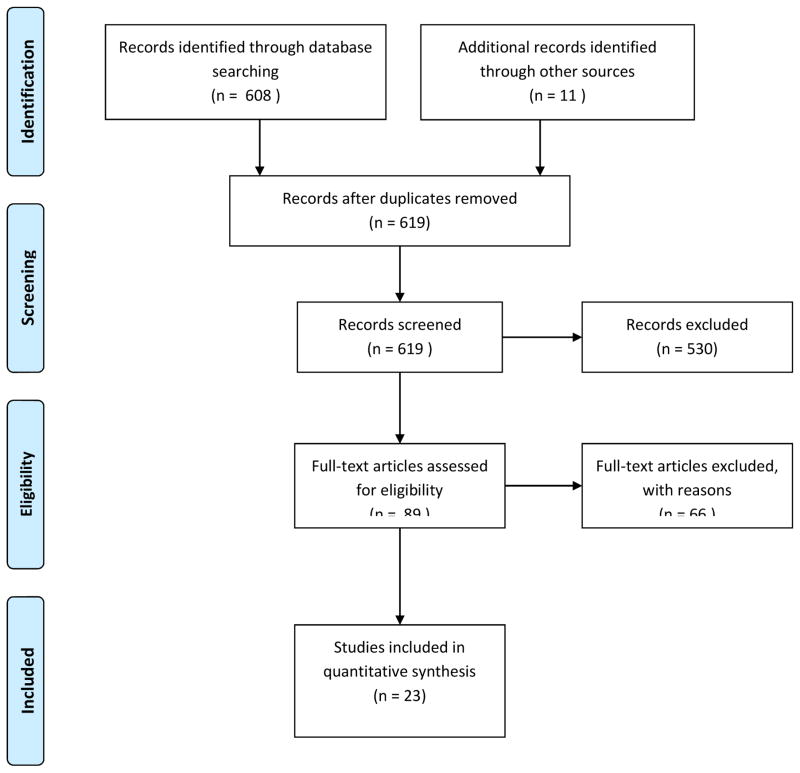

We reviewed abstracts and identified 608 articles;85 full-text articles were reviewed yielding 19 articles. After identification of all measures used to quantify childbirth self-efficacy within the original 19 articles; one additional article was identified through measure-citing sources. A review of citations of these 20 publications identified three additional articles for a total of 23 articles meeting inclusion criteria for this review. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Childbirth self-efficacy literature search and inclusion.

Theory and Measurement

Two important patterns emerged from this integrative review regarding theory and measurement (Table 1). First, all of the studies employed Bandura’s framework and definition of self-efficacy, citing either Bandura or Lowe. Second, more than half of the studies (16 of 23) used the Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory (CBSEI; Lowe, 1993). The CBSEI is a 62-item measure that has two subscales for efficacy expectations and two for outcome expectations. The reliability and validity of the CBSEI has been supported across a variety of populations (Cunqueiro, 2009; Gao, Ip, & Sun, 2011; Sinclair & O’Boyle, 1999).

Table 1.

Design, Intervention, Measurement Tool, Theory Cited

| First author | Design | Intervention | Measurement | Theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwartz 2015 | Secondary analysis; cross-sectional, descriptive | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Byrne 2014 | Single arm pilot; Repeated measures/ | Mindfulness-Based Childbirth Education | CBSEI | Lowe |

| Larsen 2012 | Quasi experimental | Childbirth education | Proprietary | Bandura |

| Hui Choi 2012 | Cross-sectional, descriptive | -- | Locus of Control | Bandura |

| Goutoudier 2012 | Prospective longitudinal | -- | CBSEI | Lowe |

| Rhamipavar 2012 | Randomized controlled trial | Childbirth educational software | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Gau 2011 | Randomized controlled trial | Antepartum birth ball antepartum exercise classes; Intrapartum encouragement to use birth ball | CBSEI | Lowe |

| Kennedy 2011 | Randomized controlled trial | Centering Pregnancy group prenatal care | CBSEI | Lowe |

| Sun 2011 | Quasi-experimental | Prenatal yoga | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Svensson 2009 | Randomized controlled trial | Childbirth education | Proprietary | Bandura |

| Ip 2009 | Randomized controlled trial | Childbirth education | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Berentson-Shaw 2009 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Williams 2008 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Christiaens 2007 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | Mastery | Bandura |

| Beebe 2007 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Seiber 2006 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Soet 2003 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Larsen 2001 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | Proprietary | Bandura |

| Stockman 2001 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | Proprietary | Bandura |

| Slade 2000 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | Proprietary | Bandura |

| Lowe 2000 | Descriptive cross-sectional | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Dilks 1997 | Descriptive cross-sectional | -- | CBSEI | Bandura |

| Manning 1983 | Longitudinal descriptive | -- | Proprietary | Bandura |

Note. CBSEI = Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory; -- = no intervention

In the seven articles in which the CBSEI was not used, investigators developed their own childbirth self-efficacy tools. In two of these studies, researchers reported childbirth self-efficacy measures with acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha .70-.93) (Larsen, O’Hara, Brewer, Wenzel, 2001; Larsen & Plog, 2012); the remaining five authors either did not report metrics of internal consistency (Manning & Wright, 1983; Stockman, 2001; Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2009), or reported low internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha .59) (Slade, Escott, Spiby, Henderson, & Fräser, 2000). Other researchers used tools that were designed to measure phenomena other than self-efficacy including locus of control (Hui Choi, 2012) and mastery (Christiaens & Bracke, 2007). Overall, common theoretical underpinnings and measurement identified in the literature review led to more robust synthesis across studies whereas integrating findings from studies using disparate measures was not as straightforward.

Samples

Samples included across these studies were homogeneous (Table 2). Overall, participants were within the racial majority where the study was sited, married or partnered, well-educated, with high income, and were either recruited from childbirth education classes or were able and willing to participate in antenatal interventions. These sample characteristic similarities may influence childbirth self-efficacy and therefore limit generalizability of this body of research to women within different communities, such as those who are socially marginalized.

Table 2.

Sample

| First Author, year of publication, country | N | % Recruited | % Attrition | % Nullip | Race / Ethnicity | Married or partnered | Annual Income | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwartz 2015 Australia | 1410 | 61% | * | 43% | 74% Australian born | 93% | • | 50% post year 12 |

| Byrne 2014 Australia | 12 | • | 67% | 100% | • | 89% | • | 78% undergraduate or higher degree |

| Larsen 2012 U.S. | 115 | • | 78% | 96% | • | 79% | 80% >/= $40,000 | 53% college or higher degree |

| Hui Choi 2012 Hong Kong | 550 | 82% | 10% | 37% | • | 86% | 52% >/= HK $20,000 | 71% secondary school education |

| Goutoudier 2012 France | 98 | 99% | 22% | 50% | • | • | • | 61% college or higher degree |

| Rhamipavar 2012 Iran | 150 | 100% | 3% | 100% | • | • | 25% ‘adequate income’ | 61% diploma or higher degree |

| Gau 2011 Taiwan | 87 | 86% | 50% | 63% | • | • | • | 80% college or higher degree |

| Kennedy U.S. 2011 | 322 | 88% | 4% | 53% | 59% Caucasian; 19% African American | 59% | • | 16% college or higher degree |

| Sun 2011 Taiwan | 88 | • | 8% | 100% | • | • | • | 30% college or higher degree |

| Svensson 2009 Australia | 170 | • | 32% | 100% | 81% Born AU.S., NZ, or UK | • | 92% >/= 40,000 | 84% diploma or higher degree |

| Ip 2009 Hong Kong | 133 | 53% | 31% | 100% | • | 93% | 40% >/= $2564 in U.S. dollars | 83% secondary form 3–7 or higher degree |

| Berentson-Shaw, 2009 New Zealand | 230 | • | 11% | 100% | 82% European | • | ‘higher mean income’ | ‘higher mean education’ |

| Williams, 2008 UK | 100 | 59.3% | • | 48% | • | 89% | • | 74% at A-level standard or higher degree |

| Christiaens, 2007 Belgium + the Netherlands | 560 | Hospitals 19–68% Midwifery 38–100% | 7.5% | Belgian 48%, Dutch 52% | • | Belgian 98% Dutch 99% | • | Belgian 77%, Dutch 41% ‘completed higher education’ |

| Beebe 2007 U.S. | 35 | • | 13% | 100% | 89% Caucasian | 100% | 66% > $50,000 | 51% college or higher degree |

| Seiber 2006 Switzerland | 61 | • | 16% | 100% | • | 96.7% | • | 41% university or advance technical college |

| Soet 2003 U.S. | 103 | • | 8.0% | 92% | 67% Caucasian 28% African American | 91% | 63% >/= $50,000 | 70% college or higher degree |

| Larsen 2001 U.S. | 37 | • | 43.1% | 100% | • | • | • | • |

| Stockman 2001 U.S. | 43 | 95% | 81% | 21% | 100% Caucasian | 95% | 76% >/= $40,000 | 58% college or higher degree |

| Slade 2000 U.S. | 121 | 87% | • | 100% | • | • | • | • |

| Lowe 2000 U.S. | 280 | 79% | * | 100% | 92% Caucasian | 90% | 50% >$40,000 | 61% college |

| Dilks 1997 U.S. | 74 | 33% | * | 40.5% | 83.8% Caucasian | ‘the majority’ | 58.6% > $50,000 | mean education = 16.4 years (SD 3.4 years) |

| Manning 1983 U.S. | 52 | • | 26.9% | 100% | • | • | • | • |

Note. = inadequate information;

= cross-sectional study design

Racism can be conceptualized as a force that undermines an individual’s confidence; therefore, the experience of racism could influence women’s childbirth self-efficacy scores. Of the 17 studies conducted in North America or Europe, only one recruited a larger number of non-White participants. Soet et al. (2003) recruited participants including 33 African American women (27%) in a longitudinal descriptive study of childbirth self-efficacy (Soet et al., 2003). Because outcomes of childbirth self-efficacy were not differentiated by race, however, of the researchers offer no insight into the role that race may or may not play in differences and/or disparities in childbirth self-efficacy. Childbirth self-efficacy research on women of racial majority in China (Gau et al., 2011; Hui Choi, 2012; Ip, Tang, & Goggins, 2009; Sun, 2010) and Iran (Vasegh Rahimparvar, Hamzehkhani, Geranmayeh, & Rahimi, 2012) has provided evidence that self-efficacy outcomes are similar comparing Caucasian and non-Caucasian women. It is important to note again, however, that we know very little about childbirth self-efficacy among women within racial minority communities.

With few exceptions, all studies measuring childbirth self-efficacy included predominantly married/partnered participants with higher than average income and/or education. Only Vasegh Rahimparvar et al. (2012) intentionally recruited women with lower incomes (Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012). In the eight articles that did not clearly report income level, only Larsen et al. (2001) and Slade et al. (2000) did not report both income and education level (K. E. Larsen et al., 2001; Slade et al., 2000). In summary, it is likely that a great majority of the literature measuring childbirth self-efficacy includes participants with higher than average education and income. These characteristics are important because the relationship support, financial security, and privileges associated with education are factors that theoretically could enhance childbirth self-efficacy.

Participants in these studies were frequently recruited from childbirth education classes (Beebe, Lee, Carrieri-Kohlman, & Humphreys, 2007; Larsen et al., 2001;Larsen & Plog, 2012; N. K. Lowe, 1993; Manning & Wright, 1983; Slade et al., 2000; Soet et al., 2003; Svensson et al., 2009) or were required to complete time intensive antenatal interventions to remain in the final sample for analysis (Backstrom & Hertfelt Wahn, 2011; Gau et al., 2011; Kennedy et al., 2011; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012; Sun, 2010; Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012). A lack of information about percent recruited or evidence of low recruitment characterizes most of the literature reviewed, with only seven studies clearly documenting effective recruitment (Goutaudier et al., 2012; Hui Choi, 2012; Kennedy et al., 2011; Lowe, 1993; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012; Slade et al., 2000; Stockman, 2001). High attrition rates in several studies (24%–54%) suggest that study requirements often were untenable (Gau et al., 2011; Ip et al., 2009; Kennedy et al., 2011; Larsen et al., 2001; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012; Soet et al., 2003; Svensson et al., 2009). Women willing to participate in childbirth education classes and who persist in childbirth self-efficacy studies and interventions may have different abilities to cultivate childbirth self-efficacy than women who do not persist in these activities.

Nulliparous versus multiparous

One of the four sources of self-efficacy is performance accomplishment (Bandura, 1977). Perinatal events are unique experiences (Lowe, 1991); therefore, the only method by which a woman may build performance accomplishments for childbirth self-efficacy is through experiencing the childbearing cycle. Of the 11 studies that included both multiparous and nulliparous women, two studies had insufficient (4–8%) multiparous women to permit comparisons by parity (Larsen & Plog, 2012; Soet et al., 2003). In nine studies, researchers reported more robust inclusion of multiparous women (31% – 79%;Christiaens & Bracke, 2007; Dilks, 1997; Gau et al., 2011; Goutaudier et al., 2012; Hui Choi, 2012; Kennedy et al., 2011; Schwartz, 2015; Stockman, 2001; Williams et al., 2008).

However, in seven of these studies, researchers did not report childbirth self-efficacy outcomes by parity. To illustrate, Hui Choi (2012) identified childbirth self-efficacy as one of four variables associated with improved prenatal psychosocial adaptation; however, only prenatal psychosocial adaptation scores and not childbirth self-efficacy scores were reported by parity.

Only Dilks (1997) and Schwartz et al. (2015) formally evaluated and reported childbirth self-efficacy by parity. In a descriptive, cross-sectional study, a convenience sample of 74 pregnant women, nulliparous or multiparous, with a history of cesarean delivery, were recruited through prenatal clinics or childbirth education classes in the Northeastern U.S. (Dilks, 1997). Dilks et al. (1997) concluded that childbirth self-efficacy of multiparous women planning vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) was equivalent to childbirth self-efficacy of nulliparous participants while multiparous women planning a repeat cesarean section had lower childbirth self-efficacy than nulliparous women or multiparous women planning a VBAC. Because these researchers associated prior mode of delivery and not parity with childbirth self-efficacy, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the influence of parity on childbirth self-efficacy.

Schwartz et al. (2015) helped to address this gap in their descriptive study in which 57% of the sample (n = 801) were multiparous. Though childbirth self-efficacy outcome expectancy did not differ significantly by parity, investigators found that multiparous women in this sample had significantly higher childbirth self-efficacy than did nulliparous women. This supports Bandura’s theory that prior experience significantly increases self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). If these findings are replicated it may be that future childbirth self-efficacy interventions should be tailored by parity.

Low-perinatal risk versus high-perinatal risk

Prior to or during the perinatal period, a woman may develop medical conditions increasing her risk for perinatal complications. For example, pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia are at significantly increased risk for medically indicated preterm (Ananth, 1997) and cesarean birth (Backes, 2011) delivery. Higher perinatal risk status might influence childbirth self-efficacy scores; therefore, identifying the perinatal risk status of women recruited to studies measuring the effect of childbirth self-efficacy on perinatal outcomes is likely important. In only three studies did the researcher discrimintate childbirth self-efficacy by perinatal risk status of participants (Berentson-Shaw, 2009; Dilks, 1997; Vasegh Rahimparvar, 2012) Moreover, Vasegh Rahimparvar et al. (2012) were the only researchers who specified ‘high perinatal-risk’ for their study. In listing exclusion criteria, these authors specified 15 diagnoses as meeting criteria for ‘complication in pregnancy’ (Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012). Dilks’ (1997) assessed childbirth self-efficacy in relation to the high perinatal risk of intended vaginal trial of labor (VTOL); perinatal risk status of nulliparous participants was not specified in this study. Finally, Berentson-Shaw’s (2009) longitudinal descriptive investigation (n=230) included 25 participants identified as having a ‘high risk pregnancy’ though a definition is not offered. These authors found that childbirth self-efficacy scores were not significantly correlated with ‘high risk pregnancy’ status. Therefore, only preliminary ideas can be formed regarding the influence of perinatal risk-status on childbirth self-efficacy.

Outcomes

Although a wide variety of outcomes was examined, the majority of research findings on childbirth self-efficacy indicated either that childbirth self-efficacy is modifiable or that better childbirth self-efficacy is associated with improved perinatal outcomes (Table 3). The two areas with the most consistently positive associations were between: the increase of antepartum and intrapartum childbirth self-efficacy after prenatal efficacy enhancing interventions, and higher childbirth self-efficacy and decreased childbirth pain and suffering (defined as emotional or cognitive distress) during labor. More preliminary research links higher childbirth self-efficacy with improved parenting outcomes.

Table 3.

Design/Intervention, Childbirth Self-Efficacy Outcomes by phase of Childbearing Cycle: Antepartum, Intrapartum, and Postpartum

| First author | Design / Intervention | Antepartum Outcomes | Intrapartum Outcomes | Postpartum Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwartz 2015 | Secondary analysis; cross-sectional, descriptive | self-efficacy higher among multiparous women | ||

| Byrne 2014 | Single arm pilot; Repeated measures/Mindfulness-Based Childbirth Education | 1 | ||

| Larsen 2012 | Quasi experimental/Childbirth education | 1 | ||

| Hui Choi 2012 | Cross-sectional, descriptive | 2 (increased psychosocial adaptation to pregnancy) | ||

| Goutoudier 2012 | Prospective longitudinal | 4 (self-efficacy measured 2–3 days postpartum did not predict PTSD at 6 weeks postpartum) | ||

| Rhamipavar 2012 | RCT / Childbirth educational software | 1 | ||

| Gau 2011 | RCT / Antepartum birth ball antepartum exercise classes; Intrapartum encouragement to use birth ball | 1 | 1 2 (lower active labor pain scores) |

|

| Kennedy 2011 | RCT / Centering Pregnancy group prenatal care | 3 | ||

| Sun 2011 | Quasi-experimental / Prenatal yoga | 2 (decreased end of pregnancy discomforts) | 1 (increased childbirth self-efficacy in active first and second stage labor) | |

| Svensson 2009 | RCT / Childbirth education | 1 | 2 (increased parenting self-efficacy and knowledge) | |

| Ip 2009 | RCT / Childbirth education | 2 (lower active labor pain and suffering) 4 (did not predict pain of transition) |

||

| Berentson-Shaw 2009 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (lower active labor suffering and higher satisfaction with birth) | ||

| Williams 2008 | Longitudinal descriptive | 4 (not associated with women’s intentions to use pain medication) | ||

| Christiaens 2007 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (higher satisfaction with self, midwife, and physician related aspects of birth) | ||

| Beebe 2007 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (decreased anxiety) | 4 (not associated with early labor pain scores) | |

| Seiber 2006 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (not associated with stronger identification with motherhood role) | ||

| Soet 2003 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (decreased symptoms post-traumatic stress disorder) | ||

| Larsen 2001 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (lower active labor pain and suffering) 4 (did not predict transition pain) |

||

| Stockman 2001 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (lower latent and active labor pain and suffering) 4 (not associated with length of labor or rates of anesthesia use) |

||

| Slade 2000 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (greater intention to avoid labor pain medication) | ||

| Lowe 2000 | Descriptive cross-sectional | 2 (decreased fear of labor) | ||

| Dilks 1997 | Descriptive cross-sectional | 2 (greater VBAC intention) | ||

| Manning 1983 | Longitudinal descriptive | 2 (greater capacity to cope with active labor and less suffering in active labor) |

Note. 1 = evidence that intervention significantly increased childbirth self-efficacy scores; 2 = evidence that increased prenatal childbirth self-efficacy scores significantly associated with improved outcomes; 3 = no evidence that intervention increased childbirth self-efficacy scores; 4 = no evidence that increased prenatal childbirth self-efficacy scores associated with improved outcomes; PTSD = post traumatic stress disorder; RCT = randomized controlled trial; VBAC = vaginal birth after cesarean.

Antepartum period

With nine months in which a woman might build self-efficacy, the antenatal phase is the most logical of the three perinatal phases in which to effect change in this psychosocial variable. Thus, researchers who explored modifying childbirth self-efficacy or found associations with levels of childbirth self-efficacy during pregnancy are particularly important. Fourteen studies. In nine of these, findings supported that childbirth self-efficacy could be increased through interventions (Gau et al., 2011; Ip et al., 2009; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012; Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012), or that increased prenatal childbirth self-efficacy was associated with decreased end of pregnancy discomforts (Sun, 2010), prenatal anxiety (Beebe et al., 2007), fear of labor (Lowe, 1993), better psychosocial adaptation to pregnancy (Hui Choi, 2012), or more confidence in requesting pain medication (Larsen & Plog, 2012). Importantly, Larsen’s et al.’s (2012) results did not support the hypothesized self-efficacy enhancing effect of the intervention (Larsen et al., 2012). Only one group founds no positive effect, Kennedy et al.’s (2011) study did not find an association between a group prenatal care model and increased childbirth self-efficacy scores (Kennedy et al., 2011).

The association between higher childbirth self-efficacy and pregnant women’s intentions for care was examined in three studies. Dilks (1997) found that participants with high childbirth self-efficacy had higher intention to attempt vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), while Slade et al. (2000) determined that those with higher childbirth self-efficacy had greater intention to use non-pharmacological pain coping strategies during labor. Williams et al. (2008) examined the intention to use non-pharmacological methods to cope with labor and did not find an association with childbirth self-efficacy. However, it should be noted that this cross-sectional study utilized CBSEI scores as a proxy for measuring participants’ beliefs regarding non-pharmaceutical pain management methods which limits confidence in this study’s findings (Williams et al., 2008). In conclusion, of the 13 studies, ten groups of researchers found that interventions could increase childbirth self-efficacy or that higher childbirth self-efficacy was associated with improved outcomes. Hence, childbirth self-efficacy may be a psychosocial variable which can be strengthened during pregnancy and this strengthening may lead to better outcomes for pregnant women.

Intrapartum period

In nine studies researchers examined intrapartum outcomes, with the majority exploring the association between childbirth self-efficacy and various aspects of labor pain or suffering. Eight groups of investigators found positive association between increased childbirth self-efficacy and improved capacity to cope with active phase labor pain (Manning & Wright, 1983), lower active labor pain (Gau et al., 2011; Ip et al., 2009; Larsen et al., 2001) and less suffering during active labor (Berentson-Shaw et al., 2009; Ip et al., 2009; Manning & Wright, 1983; Stockman, 2001). Childbirth self-efficacy did not predict pain scores during early labor in the one study that examined this phase of labor (Beebe et al., 2007), nor during transition in the two studies that examined this phase of labor (Ip et al., 2009; Larsen et al., 2001). The findings by Slade et al. (2000) that the association between high childbirth self-efficacy and high intention to use non-pharmacological coping methods did not lead to actual use of coping methods during labor are limited by the sampling and measurement issues previously detailed.

The overall consistency of these findings linking increased childbirth self-efficacy and decreased pain and suffering during active labor indicates that childbirth self-efficacy may be an important psychosocial variable for understanding how to improve a woman’s experience of labor. These findings are important because active phase labor pain is consistently identified both as the most significant physical pain most women will ever experience and also as a ‘complex, subjective, multidimensional response’ to the sensations of birthing (Lowe, 2002, p. 16). As well, a woman’s experience of labor pain or suffering may, like fear and stress, play an important role in increasing or decreasing her risk for perinatal morbidities.

Three research groups (Gau et al, 2011; Sun, 2010; Svensson et al., 2009) investigated hypothesized childbirth self-efficacy enhancing interventions proposed to positively affect intrapartum phase perinatal outcomes. Of these, findings from one quasi-experimental and one randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated that efficacy-enhancing interventions increased childbirth self-efficacy during labor (Gau et al., 2011; Sun, 2010) while a second RCT did not find an association between a self-efficacy enhancing intervention and increased childbirth self-efficacy during labor (Svensson et al., 2009). Although the Sun (2010) study suffered from common sampling concerns described previously, the Gau et al. (2011) study suffered from design concerns that obscure findings; these will be detailed. The Svensson et al. (2009) study also cannot offer strong insight to the potential link between childbirth self-efficacy and enhanced perinatal outcomes in the intrapartum phase because the intervention studied was primarily focused on increasing parenting self-efficacy. Given the importance of decreasing women’s pain and suffering during labor and the possibility that minimizing pain and suffering during labor could improve either women’s birth experiences or morbidities, stronger childbirth self-efficacy interventional trials intended to improve intrapartum outcomes are needed.

Although pain and suffering during labor are important phenomenon for investigation, measures of satisfaction are also significant both as a proxy for patient experience and because satisfaction measures have become important drivers of reimbursement and policy decisions (National Quality Forum, 2014). Two groups of researchers who explored women’s satisfaction with their births found that higher childbirth self-efficacy was significantly associated with higher satisfaction (Berentson-Shaw et al., 2009; Christiaens & Bracke, 2007). In summaryn, nine groups of researchers examining the effect of childbirth self-efficacy on intrapartum outcomes found positive associations between higher childbirth self-efficacy scores and enhanced intrapartum perinatal outcomes but three studies did not find a positive association.

Postpartum period

Four groups of researchers examined association between childbirth self-efficacy scores and perinatal outcomes in the postpartum phase. Increased childbirth self-efficacy was associated with decreased symptoms of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in one investigation (Soet et al., 2003) but was not associated with this outcome in another (Goutaudier et al., 2012). More consistency of results was evident in research related to parenting: enhanced childbirth self-efficacy was positively associated with stronger identification with the motherhood role (Sieber et al., 2006), and both increased perceived parenting self-efficacy and parenting knowledge (Svensson et al., 2009). Mixed findings regarding postpartum PTSD cannot indicate whether childbirth self-efficacy might change this postpartum outcome, but the preliminary cumulative evidence linking increased antenatal childbirth self-efficacy scores to improved parenting outcomes is of interest because it suggests the possibility that increasing pregnant women’s confidence might lead to strengthened psychosocial capacities during early motherhood. Mothers’ greater confidence and calm has been shown to positively affect children’s mental health outcomes (Gross & Rocissano, 1988) thus opening the possibility that higher maternal childbirth self-efficacy could strengthen children’s well-being.

Study Design

Literature quantifying childbirth self-efficacy and its influence on perinatal outcomes range in study design and include descriptive, quasi-experimental, and experimental studies. Of the 15 descriptive studies, two groups of researchers did not find that better childbirth self-efficacy was associated with improved perinatal outcomes (Goutaudier et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2008) and one group found mixed results, showing that higher childbirth self-efficacy was associated with decreased labor pain but was not associated with anesthesia use or length of labor (Stockman, 2001). In the remaining descriptive studies, higher childbirth self-efficacy was identified as significantly and positively associated with multiparity (Schwartz, 2015) and several outcomes including: reduced labor pain and suffering (Larsen et al., 2001; Manning & Wright, 1983); enhanced satisfaction with birth (Berentson-Shaw et al., 2009); and decreased fear or anxiety related to birth (Beebe et al., 2007; Lowe, 2000). Studies with descriptive design regarding measures of childbirth self-efficacy cannot provide causality, but the consistency of positive associations between childbirth self-efficacy and outcomes across these studies is compelling.

Findings from studies with quasi-experimental design indicate that childbirth self-efficacy could be increased through either a prenatal yoga intervention (Sun, 2010) or a childbirth education intervention (Larsen & Plog, 2012) and that higher childbirth self-efficacy was associated with improved perinatal outcomes, such as fewer end of pregnancy discomforts. Women who chose to participate in Sun’s (2010) study of prenatal yoga as an efficacy enhancing intervention were noted to be highly motivated; 92% of these women persisted in 14 weeks of thrice weekly, thirty minute, yoga exercise sessions. Women who chose epidural anesthesia during labor or who delivered via cesarean section were excluded from the study. Women who are highly motivated, persistent, choose epidurals, or deliver via cesarean may have differing levels of childbirth self-efficacy, and this study design may have confounded the reported relationship between childbirth self-efficacy and the yoga exercise intervention.

Study weaknesses can also be noted in the Larsen study (2012). In addition to the previously detailed incongruence between self-efficacy theory and findings that women who received the intervention significantly increased their confidence in asking for pain medication, the two interventional childbirth education program options were quite different in length (6 weekly 2.5 hour classes vs. one 7-hour class) but outcomes were not evaluated by class because the authors claim that the classes were comparable. Another concern with this study is that women and partners, whose self-efficacy was compared post-intervention, averaged such differing quantities of overall childbirth preparation apart from the classes (44.59 hours vs. 14.96 hours, p<.000) that cross group comparison regarding the effect of the class is difficult. Quasi-experimental studies regarding childbirth self-efficacy must be interpreted with awareness of these design flaws.

Researchers utilizing RCTs investigated the possibility that childbirth self-efficacy could be increased through education (Ip et al., 2009; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012; Svensson et al., 2009; Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012), prenatal care model (Kennedy et al., 2011), or exercise interventions (Gau et al., 2011). In addition, these six groups of researchers assessed the influence of higher childbirth self-efficacy on perinatal outcomes. With the exceptions of two studies (Kennedy et al., 2011; Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2009), positive associations were found between: (a) self-efficacy enhancing interventions and higher post-intervention childbirth self-efficacy, and (b) higher childbirth self-efficacy and better perinatal outcomes (Gau et al., 2011; Ip et al., 2009; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012; Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012). We identified unique study design strengths and weaknesses in each experimental study. Study design limitations will be noted in three experimental studies followed by more detailed assessment of the one experimental study with fatal flaws and the two experimental studies with strongest designs.

Experimental studies evidencing more moderate strengths and weaknesses include two that did not find a positive association between the hypothesized childbirth self-efficacy enhancing interventions and enhanced perinatal outcomes. One group of researchers encountered cross-contamination between groups (Kennedy et al., 2011) while the other group examined an intervention predominantly focused on parenting self-efficacy rather than childbirth self-efficacy (Svensson et al., 2009).

Of the experimental studies only one had a design that obscures findings. Gau et al.’s (2011) randomized 188 pregnant Taiwanese women to either participate in a prenatal exercise program utilizing a birth ball (intervention) or to receive standard of care which did not include any specific exercise instruction (control). Women in this study randomized to the experimental arm met every two weeks with researchers prior to labor; this did not parallel the attention devoted to the control group. As well, women in the experimental arm during labor received both hourly nursing encouragement to engage birth ball exercises, which required moving out of a recumbent position, and their partners were instructed to record the quantity of time that the laboring women were standing. Those in the control arm did not receive similar interactions. Upright positions during labor have been associated with both shorter labors and also with increased capacity to cope with labor pain (Adachi, Shimada, & Usui, 2003; Lawrence, Lewis, Hofmeyr, Dowswell, & Styles, 2009). The higher average quantity of time upright during labor (181.3 minutes vs. 115.8 minutes, p=0.001) noted in those randomized to the experimental arm confounds interpretation of the birth ball exercise program on childbirth self-efficacy and outcomes.

Two experimental studies with stronger methodological design include one in which 150 low-risk, nulliparous, Iranian women were randomized to receive a self-efficacy based educational software CD between 28–32 weeks of pregnancy (intervention) versus standard of care (control) (Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012), and another which randomized 133 nulliparous, Chinese women to receive two ninety-minute sessions of self-efficacy based prenatal education (intervention) versus standard of care (control) (Ip et al., 2009). Several design strengths are noted in both of these experimental trials, including appropriately blinding research assistants to participants’ randomization, taking precautions to prevent cross-contamination, retaining equally high numbers of participants in experimental and control arms, and using power analysis to determine sample size necessary to calculate significance. Both groups of researchers showed that women randomized to intervention groups significantly increased their childbirth self-efficacy (Ip et al., 2009; Vasegh Rahimparvar et al., 2012). And although labor or postpartum outcomes were not assessed, Ip et al. (2009) found that higher childbirth self-efficacy was correlated with improved maternal coping and decreased pain and anxiety during the first two stages of labor.

In these two stronger experimental studies, consistent with the overall findings of the six quasi-experimental and less well-controlled experimental as well as the 15 descriptive studies, researchers identifed childbirth self-efficacy as an important psychosocial variable that is likely modifiable and may significantly effect perinatal outcomes. In summary, higher childbirth self-efficacy was associated with enhanced perinatal outcomes in the majority of descriptive studies and in the better designed quasi-experimental and experimental studies. The majority of evidence within this body of literature identified childbirth self-efficacy as an important psychosocial variable for investigation of the perinatal period.

Discussion

The goal of this review was to synthesize the literature regarding measurement of childbirth self-efficacy, evaluate whether childbirth self-efficacy might inform the development of interventions to improve perinatal outcomes, and clarify directions for future research. The review includes 23 studies published in peer-reviewed journals and spanning over 30 years of science located through the search methods described that met the established inclusion criteria and.

Based on an analysis of this literature, the majority of evidence, and particularly the evidence produced by stronger studies within this body of literature suggest that: (a) increased childbirth self-efficacy is associated with a wide variety of improved perinatal outcomes, and (b) childbirth self-efficacy can be modified through efficacy-enhancing interventions. These conclusions were facilitated by evidence that the majority of studies within this literature were focused on the same psychosocial phenomenon; this is made clear through overall cohesiveness in definition, citation, and capacities ascribed to childbirth self-efficacy. Synthesis was further facilitated by evidence that most of the studies utilized a well-validated tool for measuring childbirth self-efficacy; future investigation should employ only well-validated instruments.

In our literature synthesis we found multiple areas of homogeneity within study samples, including populations outside of North America and Europe. These findings indicate that current understandings of childbirth self-efficacy can only be generalized to a relatively small population of women, indicating a threat to external validity. We identify a need for recruitment and retention of more racially and economically diverse samples, including women with lower educational attainment, not participating in childbirth preparation classes, with lower motivation to persist in childbirth preparation activities, and without marital or partner support. We also suggest the need for more clarity in defining the perinatal risk status of participants and for inclusion and comparison of multiparous versus nulliparous participants, as important directions for future researchers.

Because most descriptive evidence shows that enhanced childbirth self-efficacy is associated with positive perinatal outcomes, future scientific attention should use experimental and quasi-experimental study designs when possible to advance knowledge toward causal relationships. This research could build scientific understanding through designs that strive to maximize scientific control, including factors that have not been consistently well-addressed in the literature to date, such as limiting confounders, blinding investigators and care providers, and minimizing threats to internal validity. Future research could contribute to the state of the science through building upon the identified experimental studies with the most promising findings and then reporting interventions with sufficient detail to enable replication studies. Given the extremely wide variety of perinatal outcomes that have been examined, future researchers will enhance understanding through thoughtfully selecting and explicitly defining perinatal outcomes.

Three areas of particular interest for future research emerge from this review. First related to the consistently strong association between increased childbirth self-efficacy and decreased pain or suffering during active labor; investigators should build on Ip et al.’s (2009) findings to explore how self-efficacy enhancing antenatal preparation might lead to laboring women’s decreased pain and suffering in the active phase of labor. Second, related to the multiple quasi-experimental and experimental studies demonstrating that antenatal interventions could be effective in increasing childbirth self-efficacy; investigators should examine the study by Vasegh Rahimparvar et al. (2012) an exemplary childbirth self-efficacy experimental study and also should create self-efficacy based interventions that address Bandura’s four sources of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977).

Finally, the two studies showing improved parenting outcomes related to higher childbirth self-efficacy open interesting possibilities. Future researchers might explore the possibility that building women’s childbirth self-efficacy during pregnancy could be an effective strategy for improving early parenting outcomes with the broader goal of enhancing outcomes for young children or childbearing families as a whole. Working within a traditional medical framework which proposes that the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum phases are separate, Bandura’s theory cannot explain why increased antenatal childbirth self-efficacy should result in enhanced parenting outcomes. If an association between higher antenatal childbirth self-efficacy and improved early parenting outcomes is consistently replicated, this could suggest that psychosocial factors relevant to the perinatal period may have been artificially separated into the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum through medical convention. If this is true it will be appropriate to re-conceptualize the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum perinatal phases into a unified phenomenon and self-efficacy domain of the childbearing trajectory; this could be termed the childbearing transition.

Conclusion

Although approaches to facilitating women’s success during the perinatal period have been the focus of research for decades, there are factors that now increase the need for knowledge in this area. Psychological, physical, and financial costs for poor outcomes are substantial and growing. The U.S. ranks well below other comparable countries in perinatal morbidity and mortality rates (Kassebaum, 2014; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2012). Unnecessary cesarean delivery rates have led to higher healthcare costs (Barrett, 2013; “The Costs of Having a Baby in the United States,” 2013; Menacker & Hamilton, 2010) and correlate with rising maternal morbidity (Menacker & Hamilton, 2010) and mortality (Kassebaum, 2014). Recognizing that a woman’s childbirth self-efficacy appears to influence antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum events identifies the exciting possibility that interventions for increasing childbirth self-efficacy may positively influence perinatal outcomes. These factors lend urgency to advancing this scientific field.

Biographies

Ellen L. Tilden, PhD, CNM, is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR.

Aaron B. Caughey, MD, PhD, MPP, MPH, is a professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Associate Dean for Women’s Health Research and Policy, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR.

Christopher S. Lee, PhD, RN, FAHA, FAAN, is a Carol A. Lindeman Distinguished Professor and associate professor of Nursing and Cardiovascular Medicine for Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR.

Cathy Emeis, PhD, CNM, is a director in the nurse-midwifery program, Chair for Nurse-Midwifery, and an assistant professor for Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adachi K, Shimada M, Usui A. The relationship between the parturient’s position and perceptions of labor pain intensity. Nursing Research. 2003;52(1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananth CV, Savitz DA, Luther ER, Bowes WA., Jr Preeclampsia and preterm birth subtypes in Nova Scotia, 1986 to 1992. American Journal of Perinatology. 1997;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arck P. Stress during pregnancy: maternal endocrine-immune imbalances and fetal health. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2010;86(11):67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S, Joseph S, McKenzie-McHarg K, Slade P, Wijma K. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: current issues and recommendations for future research. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;29(4):240–250. doi: 10.1080/01674820802034631. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01674820802034631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backes CH, Markham K, Moorehead P, Cordero L, Nankervis CA, Giannone PJ. Maternal preeclampsia and neonatal outcomes. Journal of Pregnancy. 2011;2011:214365. doi: 10.1155/2011/214365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backstrom C, Hertfelt Wahn E. Support during labour: first-time fathers’ descriptions of requested and received support during the birth of their child. Midwifery. 2011;27(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(2):143. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett M, Steiner C. Healthcare cost and utilization project evaluation report (HCUP) 2013 Retrieved from Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp.

- Beebe KR, Lee KA, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Humphreys J. The effects of childbirth self-efficacy and anxiety during pregnancy on prehospitalization labor. Journal of Obstetric Gynecolologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36(5):410–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berentson-Shaw J, Scott KM, Jose PE. Do self-efficacy beliefs predict the primiparous labour and birth experience? A longitudinal study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2009;27(4):357–373. [Google Scholar]

- Cervone D. Thinking about self-efficacy. Behavior Modification. 2000;24(1):30–56. doi: 10.1177/0145445500241002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaens W, Bracke P. Assessment of social psychological determinants of satisfaction with childbirth in a cross-national perspective. BioMed Central Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunqueiro MJ, Comeche MI, Docampo D. Childbirth self-efficacy inventory: psychometric testing of the Spanish version. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(12):2710–2718. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilks FM, Beal J. Role of self-efficacy in birth choice. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 1997;11(1):1. doi: 10.1097/00005237-199706000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbe S. Obstetrics: normal and problem pregnancies. 6. New York: Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon AJ, Sandall J. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(3):CD002869. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002869.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao LL, Ip WY, Sun K. Validation of the short form of the Chinese childbirth self-efficacy inventory in Mainland China. Research in Nursing and Health. 2011;34(1):49–59. doi: 10.1002/nur.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau ML, Chang CY, Tian SH, Lin KC. Effects of birth ball exercise on pain and self-efficacy during childbirth: a randomised controlled trial in Taiwan. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):e293–e300. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg R, McClure E, MacGuire E, Kamath BD, Jobe AH. Lessons for low-income regions following the reduction in hypertension-related maternal morbidity in high-income countries. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 2011;113(2):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutaudier N, Séjourné N, Rousset C, Lami C, Chabrol H. Negative emotions, childbirth pain, perinatal dissociation and self-efficacy as predictors of postpartum posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2012;30(4):352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Rocissano L. Maternal confidence in toddlerhood: a measurement for clinical practice and research. Nurse Practitioner. 1988 Mar;:19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedderson MM, Ferrara A, Sacks DA. Gestational diabetes mellitus and lesser degrees of pregnancy hyperglycemia: association with spontaneous preterm birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;102:850–856. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui Choi WHL, GL, Chan HY, Cheung YH, Lee LY, Chan LW. The relationship of social support, uncertainty, self-efficacy, and commitment to prenatal psychosocial adaptation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68(12):2633–2645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip WY, Tang CS, Goggins WB. An educational intervention to improve women’s ability to cope with childbirth. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(15):2125–2135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassebaum NJ. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2014;384:980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HP, Farrell T, Paden R, Hill S, Jolivet RR, Cooper BA, Rising SS. A randomized clinical trial of group prenatal care in two military settings. Military Medicine. 2011;176(10):1169–1177. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorsandi M. Iranian version of childbirth self-efficacy inventory. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(21) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan MD, Martin JA, Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M, Ventura SJ, Frigoletto FD. The changing pattern of prenatal care utilization in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(20):1623–1628. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KE, O’Hara MW, Brewer KK, Wenzel A. A prospective study of self-efficacy expectancies and labour pain. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2001;19(3):203–214. doi: 10.1080/02646830120073215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen R, Plog M. The effectiveness of childbirth classes for increasing self-efficacy in women and support persons. International Journal of Childbirth. 2012;2(2):107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo K, Svensson T, Li J, Obel C, Vestergaard M, Olsen J, Cnattingius S. Maternal bereavement during pregnancy and the risk of stillbirth: A nationwide cohort study in Sweden. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;177(3) doi: 10.1093/aje/kws383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, Dowswell T, Styles C. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour (Review) The Cochrane Collaboration. 2009;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003934.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz ES-BL. Self-efficacy in Nursing: Research and Measurement Perspectives. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe NK. Critical predictors of sensory and affective pain during four phases of labor. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1991;12:193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe NK. Maternal confidence for labor: development of the Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory. Research in Nursing & Health. 1993;16(2):141–149. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe NK. Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous. pregnant women. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;21:219–224. doi: 10.3109/01674820009085591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe NK. The nature of labor pain. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;186(5):S16–S24. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning MM, Wright TL. Self-efficacy expectancies, outcome expectancies, and the persistence of pain control in childbirth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45(2):421–431. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.45.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menacker F, Hamilton BE. Recent trends in cesarean delivery in the United States. Hyatsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum. Priority setting for healthcare performance measurement: Addressing performance measures and gaps in person-centered care and outcomes. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor CD, Sermer M, Chen SM, Sykora K. Cesarean delivery in relation to birth weight and gestational glucose tolerance: pathophysiology or practice style? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275:1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G. Centering Pregnancy and the current state of prenatal care. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2004;49(5):405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD health data 2012-infant mortality. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/family/CO1.1.html.

- Petrou S, Kahn K. Economic costs associated with moderate and late preterm birth: Primary and secondary evidence. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2012;17:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mirazo E, Lopez-Yarto M, McDonald SD. Group prenatal care versus individual prenatal care: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology Canada: JOGC. 2012;34(3):223–229. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L, Toohill J, Creedy DK, Baird K, Gamble J, Fenwick J. Factors associated with childbirth self-efficacy in Australian childbearing women. BioMed Central Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15(29):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber S, Germann N, Barbir A, Ehlert U. Emotional well-being and predictors of birth-anxiety, self-efficacy, and psychosocial adaptation in healthy pregnant women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85(10):1200–1207. doi: 10.1080/00016340600839742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair M, O’Boyle C. The Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory: a replication study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30(6):1416–1423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade P, Escott D, Spiby H, Henderson B, Fräser RB. Antenatal predictors and use of coping strategies in labour. Psychology and Health. 2000;15(4):555–569. [Google Scholar]

- Soet JE, Brack GA, DiIorio C. Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth. 2003;30(1):36–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman A, Altmaier E. Relation of self-efficacy to reported pain and pain medication usage during labor. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2001;8(3):161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sun YH, Chang YY, Kuo S. Effects of a prenatal yoga programme on the discomforts of pregnancy and maternal childbirth self-efficacy in Taiwan. Midwifery. 2010;26:e31–e36. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J, Barclay L, Cooke M. Randomised-controlled trial of two antenatal education programmes. Midwifery. 2009;25:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydsjo G, Sydsjo A, Gunnervik C, Bladh M, Josefsson A. Obstetric outcome for women who received individualized treatment for fear of childbirth during pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012;91(1):44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasegh Rahimparvar SF, Hamzehkhani M, Geranmayeh M, Rahimi R. Effect of educational software on self-efficacy of pregnant women to cope with labor: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2012;286(1):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C, Povey RC, White DG. Predicting women’s intentions to use pain relief medication during childbirth using the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Self-Efficacy Theory. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2008;26(3):168–179. [Google Scholar]