Abstract

Objectives

The UK 5 year antimicrobial resistance strategy recognizes the role of point-of-care diagnostics to identify where antimicrobials are required, as well as to assess the appropriateness of the diagnosis and treatment. A sore throat test-and-treat service was introduced in 35 community pharmacies across two localities in England during 2014–15.

Methods

Trained pharmacy staff assessed patients presenting with a sore throat using the Centor scoring system and patients meeting three or all four of the criteria were offered a throat swab test for Streptococcus pyogenes, Lancefield group A streptococci. Patients with a positive throat swab test were offered antibiotic treatment.

Results

Following screening by pharmacy staff, 149/367 (40.6%) patients were eligible for throat swab testing. Of these, only 36/149 (24.2%) were positive for group A streptococci. Antibiotics were supplied to 9.8% (n = 36/367) of all patients accessing the service. Just under half of patients that were not showing signs of a bacterial infection (60/123, 48.8%) would have gone to their general practitioner if the service had not been available.

Conclusions

This study has shown that it is feasible to deliver a community-pharmacy-based screening and treatment service using point-of-care testing. This type of service has the potential to support the antimicrobial resistance agenda by reducing unnecessary antibiotic use and inappropriate antibiotic consumption.

Introduction

Patients with sore throat symptoms commonly visit their general practitioner (GP), but in most cases the cause is a virus and only symptomatic treatment is needed.1 Infection with group A streptococci can cause severe disease and late complications such as scarlet fever or rarely rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis. Whilst a recent study found that serious septic complications were rare events, antibiotic treatment was associated with fewer complications.2 With the emergence of multiresistant pathogens and a limited supply of new antibiotics, antimicrobial stewardship has become central to strategies adopted by the Chief Medical Officer and The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK.3,4 Point-of-care testing (POCT) has been recognized as a means to confirm the need for appropriate antimicrobial treatment in respiratory illness.3,5 Faced with a distressed patient and the potential sequelae of bacterial pharyngitis, GPs may feel pressured to prescribe antibiotics, despite guidance to avoid or delay antibiotic use.5,6 Research by the Wellcome Trust showed that patients associate antibiotics with having ‘a real illness’ and ‘proof that they are ill’.7 They also found evidence that patients look up symptoms beforehand so that they know what to say to their GP to obtain antibiotics.

Both current NICE guidance and the UK Department of Health 5 year strategy aim to delay the development of antimicrobial resistance by targeting antibiotics to those patients in need.3,4 In a study of treatment of acute pharyngitis in 537 GP practices in England, antibiotics were prescribed in 62% of cases, despite usually being caused by viral infection, but with a wide variation between practices (45%–78%).1 In the Capibus Ipsos MORI survey in the UK, 58% of 1767 participants reported a respiratory infection in the last 6 months. A fifth had contacted the GP and 53% of them expected to receive antibiotics.8 Another 6% asked a pharmacist for advice. Of the 26% who asked a GP or nurse for antibiotics for any reason in the past year, 97% had been given them. To guide GPs in their choice of antibiotics and to limit unnecessary use, the TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) antibiotics toolkit has been introduced.9

A 2007 study looking at GP practice data estimated that 1.2 million GP consultations were for sore throats.10 A more up-to-date study has found that an average GP with a patient list of 2000 people will see around 120 patients each year for acute pharyngitis.11 The Centor scoring system is designed to pick out those patients at higher risk of infection due to group A Streptococcus pyogenes and guidelines suggest this group (with a Centor score of 3 or 4) could be offered rapid antigen detection testing (RADT) to confirm presence of the organism. In this way antibiotic use could be minimized.5 Community pharmacists are well placed to help patients to manage their symptoms and to signpost the public for further investigation if there are signs of more complex infection. Sore throat ‘test-and-treat’ services are delivered in some pharmacies in the USA and can avoid unnecessary antibiotic use.12–14 A pilot service was introduced to test the feasibility and benefit of a service run from community pharmacies incorporating RADT for patients 12 years and over presenting with sore throat symptoms according to Centor criteria.

Patients and methods

A sore throat test-and-treat service was introduced in 20 community pharmacies across central London from October 2014 and 15 pharmacies across Leicestershire from January 2015. The sites were chosen to allow evaluation of the service in a variety of locations, socioeconomic groups and types of pharmacy.

The service was developed with advice and input from a clinical advisory board comprising doctors, pharmacists and a consultant microbiologist. Trained pharmacy staff assessed the patient's presenting condition using the Centor scoring system.15 This is a four-point validated method that helps to identify the likelihood of bacterial infection in adults with a sore throat. Patients who had a history of fever and/or absence of cough were referred to the pharmacist to complete the second part of the Centor scoring system, i.e. examination of the tonsils for exudate and palpation of the neck for tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

Patients meeting three or all four of the Centor criteria were offered a throat swab test. The pharmacist would take a throat swab and test for group A streptococci using the OSOM® Strep A Test (manufactured by Sekisui Diagnostics UK Ltd, Maidstone, UK). The OSOM® Strep A Test detects either viable or non-viable organisms directly from a throat swab, providing results within 5 min (96% sensitivity; 98% specificity).

Antibiotic treatment was discussed with the patient if their Centor score was 3 or 4 and they had a positive throat swab test for group A streptococci. Penicillin V was used as first-choice treatment at a dose of two 250 mg tablets every 6 h for 10 days. If patients were allergic or unable to take penicillin tablets, one clarithromycin 250 mg tablet twice a day for 5 days was used (in line with prescribing guidelines). Antibiotics were supplied by the pharmacist under the authority of a Patient Group Direction (PGD). Throughout the service, all patients were given general written and verbal advice about managing their condition, including products to help with symptomatic relief as necessary (including TARGET principles).9

Patient examination and testing took place within a private consultation room in the pharmacy. Patients paid £7.50 for the test and a further £10 if antibiotic supply was required. The fees were calculated based on the cost of materials and staff resource to deliver the service and an estimation of the number likely to progress through each stage of the service.

Patients with atypical symptoms or a severe presentation (unilateral or chronic symptoms, signs of sepsis or recent antibiotics) were referred by the pharmacist to their GP for review. Those who had symptoms for more than 10 days, were under 12 years of age or were pregnant or breast feeding were excluded from the service. Those whose symptoms were improving or had already taken antibiotics or were immunocompromised or showing signs or symptoms that would indicate any other infection or more serious disease were also excluded. Patients with history of reaction to the antibiotics offered via the PGD were excluded.

Across the 35 pharmacies, 98 pharmacists completed a training package that included a face-to-face session on the pathophysiology of viral and bacterial throat infections, clinical examination and assessment of throats, warning signs requiring referral, swabbing technique and method for the near-patient Streptococcus A test itself. All pharmacists were also encouraged to register as Antibiotic Guardians.16 GPs located near the pilot pharmacies were made aware of the service and were able to refer patients to the pharmacy if appropriate. Patients were also made aware of the service through posters and leaflets displayed within the pharmacy and by discussion with the pharmacy staff.

Data from the consultations were collected through Boots UK pharmacies from launch of the service (London, October 2014; Leicestershire, January 2015) up to 2 May 2015. Boots UK is a member of Walgreens Boots Alliance, with headquarters in Nottingham. Anonymized copies of the standard data recorded were sent to the Boots UK head office for electronic input and analysis using Microsoft Excel 2007. Deprivation profiles were calculated using the Carstairs index.17 This is used to calculate deprivation quintiles for the least and most deprived and is based on four census indicators: low social class, lack of car ownership, overcrowding and male unemployment. A negative value indicates areas of low deprivation and a positive value equates to high deprivation. Savings to the NHS were calculated using Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) reference costs.18

Ethics

The anonymized data were collected as part of a pre-planned service audit and therefore no ethics approval was necessary.

Results

Data were analysed for 367 patients from 35 community pharmacies in London (278 patients across 20 pharmacies, range 2–62) and Leicestershire (89 patients across 15 pharmacies, range 1–13) (Figure 1). Data were collected from October 2014 to April 2015 from pharmacies in London (7 months) and January 2015 to April 2015 (4 months) from pharmacies across Leicestershire. These data represent 78.0% of patients that received the service during this time period [missing data were due to non-returns of Customer Record Forms (CRFs)].

Figure 1.

Breakdown of how many patients accessed each stage of the service.

Of all 367 patients who had the initial discussions with the healthcare assistant and for whom data are available, 149 (40.6%) were eligible for throat swab testing. Of these 149 patients, 113 (75.8%) tested negative and 36 (24.2%) were positive for group A streptococci. Antibiotics were supplied to all patients who tested positive (36/367, 9.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient subgroup analysis (n = 367)

| Sample group | Definition | Size |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | all patients accessing the service | 367 |

| Centor | patients who underwent Centor questionnaire only (score of 1 or 2) | 218 |

| Throat test negative | patients who scored 3 or 4 on Centor questionnaire and had a negative throat test result | 113 |

| Throat test positive and PGD | patients who scored 3 or 4 on Centor questionnaire and had a positive throat test result and received antibiotics | 36 |

Data on age were available for 356/367 (97.0%) patients (Figure 2). Over two-thirds (251/356, 70.5%) of patients accessing the service were aged between 16 and 44 years.

Figure 2.

Distribution of age (n = 356).

A higher proportion of women accessed the service (221/354, 62.4%) than men (133/354, 37.6%). The gender distribution across the various age bands was similar (Table 2). There were more men in the 35–44 year group than women.

Table 2.

Gender distribution across age (n = 338)

| Age (years) | Male (n = 128) | Female (n = 210) | Total (n = 338) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12–15 | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (1.4%) | 4 (1.2%) |

| 16–25 | 26 (20.3%) | 48 (22.9%) | 74 (21.9%) |

| 26–34 | 32 (25.0%) | 67 (31.9%) | 99 (29.3%) |

| 35–44 | 31 (24.2%) | 35 (16.7%) | 66 (19.5%) |

| 45–54 | 17 (13.3%) | 30 (14.3%) | 47 (13.9%) |

| 55–64 | 11 (8.6%) | 21 (10.0%) | 32 (9.5%) |

| 65+ | 10 (7.8%) | 6 (2.9%) | 16 (4.7%) |

| Missing data | 1 | 5 | 6 |

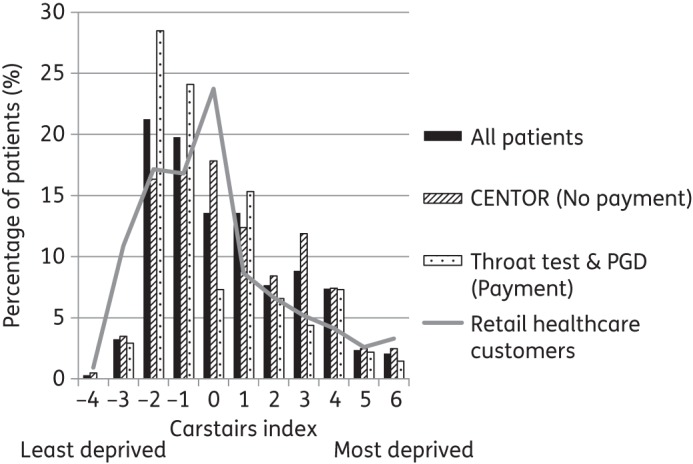

For the Carstairs analysis, data (n = 339) were analysed separately based on whether patients paid for the service (throat test ± PGD) or not (Centor assessment only). Figure 3 shows the detailed breakdown and how the profile compares with customers accessing those pharmacies for general healthcare queries and medicines. Patients from the least deprived areas (Carstairs −4 to −1) represented over half (76/137, 55.5%) of patients paying for the service and 75/202 (37.1%) of patients accessing the non-payment component. Of those paying for the service in the least deprived areas, 22/76 (28.9%) were aged between 16 and 25 years.

Figure 3.

Carstairs profiling (n = 339).

Staff recorded 1720 occasions when patients enquired about the service, but did not progress (due to ineligibility or standard pharmacy care received). This was split by weekday (Monday to Friday) and weekend (Saturday and Sunday) and then compared with the time profile of when patients accessed the service, as recorded on the CRF. The results were then calculated as rate per hour based on the opening hours of the pharmacies (Figure 4). There were more enquiries (patients not meeting the eligibility criteria or choosing not to have the service) than test and treatments delivered at the start (7 am to 9 am) and the end of the day (7 pm to 12 am) during both the weekdays and the weekends. The peak times of service delivery were between the hours of 11 am and 5 pm, when 60/76 (78.9%) of services were delivered at the weekend and 176/272 (64.7%) during the week.

Figure 4.

Profile of enquiries and services delivered shown as rate per hour.

Data were available for 356 out of 367 patients (97.0%) on method of referral into the service. Over half of patients (200/356, 56.2%) self-referred into the service, 163/356 (45.8%) were recommended to the service by a member of the pharmacy they were visiting, 13/356 (3.7%) were recommended by friends or family and 5/356 (1.4%) were signposted to the service by a GP (patients could choose multiple responses).

Data were available for 99.2% of patients (364/367) on duration of symptoms. Two-thirds of patients (235/364, 64.6%) waited 72 h or more before presenting at the pharmacy. For patients with symptoms of a possible bacterial infection (Centor score 3 or 4), but who tested negative, 87/112 (77.7%) waited 72 h or more. For swab-positive infections, over half (21/36, 58.3%) of patients presented within 48 h from the onset of symptoms. Most positive throat tests were identified where symptoms appeared within 24 h (13/36, 36.1%).

There were 56 patients (15.3% of 367) who were referred to their GP. The primary reasons were patients displaying unilateral symptoms (18/56, 32.1%), difficulty swallowing saliva (13/56, 23.2%), symptoms of a more serious infection (12/56, 21.4%) and significant voice change (12/56, 21.4%) (Figure 5). Patients could have multiple reasons for referral.

Figure 5.

Reasons patients were referred to their doctor (n = 56). Note: more than one option could be chosen.

Data were only available for 60.5% (222/367) patients on their course of action had they not accessed the service at the pharmacy (Table 3). Those not receiving antibiotic treatment were less likely to complete the questionnaire (57.1%, 189/331 compared with 91.7%, 33/36 who received antibiotics). Most would have self-treated (44.1%, 98/222) or consulted a GP (43.7%, 97/222). About half of the patients (48.8%, 60/123) that were not showing signs of a bacterial infection (Centor score 1 or 2) would have gone to the GP if the service had not been available. Of those 97 patients who would have seen a GP, 37/97 (38.1%) had a throat test, of which 22/37 (59.5%) were negative. The overall positivity rate for which antibiotics were provided was 15.5% (15/97) in this subgroup of patients. Less than one-third of these patients (32.0%, 31/97) were referred to the GP following the service based on their presenting symptoms as described in Figure 5.

Table 3.

What patients would have done if the service had not been available (patients could tick multiple responses) (n = 222)

| Option | All patients (n = 222) | Centor 1 or 2 (n = 123) | Centor 3 or 4 and throat test negative (n = 66) | Centor 3 or 4 and throat test positive and PGD (n = 33) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-treat | 98 (44.1%) | 51 (41.5%) | 33 (50.0%) | 14 (42.4%) |

| Accessed the GP | 97 (43.7%) | 60 (48.8%) | 22 (33.3%) | 15 (45.5%) |

| Pharmacist advice | 35 (15.8%) | 13 (10.6%) | 15 (22.7%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Nothing | 15 (6.8%) | 8 (6.5%) | 5 (7.6%) | 2 (6.1%) |

Possible savings to the NHS in GP consultations avoided were calculated to be £2747. This was based on the difference between the number of patients that would have seen the GP if the service had not been available (n = 97) and the number referred (n = 56) using PSSRU at a cost of £67 per consultation.18 (These calculations do not take into account the cost of delivery of the service within community pharmacies.)

Discussion

Data presented have shown that it is feasible to deliver a community-pharmacy-based screening and treatment service for sore throats using POCT. This type of service has the potential to support the antimicrobial resistance agenda by reducing unnecessary antibiotic use and inappropriate consumption.

Study limitations

Data reported were part of a service evaluation that was conducted in 35 community pharmacies over a period of 4–7 months, presenting limitations to the methodology and results. The sample size is small (due to the service not being widely advertised) and the study was performed during the winter months, so cannot be extrapolated over a full year. Whilst children average two to three times more respiratory infections per year compared with adults,5 the service was aimed at patients 12 years and over. This was due to the practicalities of carrying out examinations with younger children within the pharmacy environment and the (lack of) experience of the pharmacy staff.

Whilst we asked patients what they would have done if they had not accessed the service (to establish the number that would have accessed their GP), this provides an indication only. Estimates of those that would have been likely to have been prescribed antibiotics if they had seen their GP are based on other literature findings. A more accurate measure would have been to compare both of these elements with a control group. We also had no follow-up information for patients, so do not know whether those that were referred actually consulted their GP or not, or whether they had any complications. The test used detected Streptococcus group A, but did not pick up any other pathogens that may have caused similar symptoms. Missing data from the CRF also resulted in different sample sizes being used for the analysis.

Findings

Increasing antimicrobial resistance and lack of new agents to treat infections is one of the main health concerns of governments, the WHO and the general public alike.3,4,19 Increasing involvement of community pharmacies in primary care treatment of patients has been developing over the last 10 years, principally with a view to improving patient access and choice, as well as releasing GP resources to deal with more complex patients.20 In this service, however, the aim is to improve antimicrobial stewardship by reducing antimicrobial usage and expenditure. The service was effective in narrowing antibiotic use to <10% of those presenting and most of those were young adults. Men in the 35–44 year group were heavily represented yet are the group most difficult for primary care services to reach. Referral of patients to the GP by the pharmacy service fulfilled a potentially important role in managing the more complicated cases, especially those choosing otherwise to self-treat. Patients with proven S. pyogenes infection tended to present earlier than the rest of the population.

Patients presented from all sociodemographic areas, although surprisingly there was a skew towards those in the least deprived areas accessing the paid elements of the service. However, payment did not appear to be a barrier to patients receiving the test and antibiotics as all patients that were eligible based on their Centor score went on to access the paid elements regardless of deprivation index. More patients from deprived areas accessed the service compared with the normal profile of patients attending those pharmacies to purchase healthcare products (as shown in Figure 3).

The reduced availability of GP services at weekends did not appear to have had an effect on timing of the use of the service, as despite the number of enquiries between 7 am and 9 am and between 7 pm and 12 pm, very few patients went on to have the service. This could have been due to the patient not being eligible, choosing to receive standard pharmacy care (advice and/or product) or the patient deciding to wait to see their GP.

Other methods of screening for bacterial pharyngitis in primary care have proved effective in targeting antimicrobial chemotherapy. Screening for S. pyogenes group A on the basis of 15 patient-reported symptoms in retail health clinics was successful when local prevalence of the organism was known.21 A POCT was confirmed with throat culture or DNA probe. For every patient with streptococcal pharyngitis missed, 27 healthcare visits would be saved if patients with a low score were used to determine further action. With rapid antigen detection in another study, the likelihood of GP prescription of antibiotic fell significantly (64% versus 44%) even though antibiotics were still prescribed in 31% of cases where the rapid test was negative.22 However, in a series of 597 patients having throat swabs collected in general practice, 34% of swabs were positive for pathogenic streptococci, but one-third were not S. pyogenes group A.23 Group C and G streptococci were associated with symptoms of similar severity to those of group A. It is not known what proportion of our patients had other groups of streptococcal infection, but all septic patients were referred to a GP, and safety-netting was offered to all patients.

A different scoring system (feverPAIN) for sore throat has been assessed and been shown to be as effective as group A streptococcal antigen testing.24 The same study found that the use of antigen tests according to a clinical score provided similar benefits, but with no advantages over clinical score alone. The finding in our results of more streptococcal infections among those patients with a shorter duration of symptoms also supports the use of the feverPAIN scale. Whilst the role of testing has been discussed and debated due to lack of published evidence,3,15,25 it could prove useful in the community setting to support conversations with patients around when antibiotics are appropriate. UK primary care guidelines,26 however, still recommend the Centor scoring system for assessing sore throats and not POCT due to the limited evidence available.3,11

There is a debate about whether a lower Centor score could be used to trigger RADT.27 The management of sore throat in primary care varies greatly across the world.28 Some countries, such as the USA, France and those in Scandinavia, use RADT to guide prescription of antibiotics for tonsillitis.29 In Scandinavia, guidelines suggest using RADT in patients with two to three Centor criteria.29 In this way, antibiotics are used only in patients with symptoms of tonsillitis, but not carriers. Patients with scores of 1 or 2 may still access their GP for a consultation. Furthermore, GPs are more likely to be influenced by patients' expectations if they do not use RADT.

Conclusions

The principal benefit of this type of service would be in saving unnecessary antibiotic usage in potentially large numbers of community patients. The service demonstrated that two-thirds of patients who would have seen their GP did not need to do so. If this was extrapolated to the 1.2 million consultations that GPs see annually for sore throats,10 then an additional 800 000 patients could be potentially seen within community pharmacy. Such a service should reduce antibiotic pressure and the emergence of resistance, and further the aims of antibiotic control programmes. If the service were not available, half of the patients would self-treat, regardless of severity, such that patients could delay seeking medical attention when it was needed. If the service continues in its current format, there is a risk that patients might only access it if they have funds to pay. The impact of supporting antimicrobial stewardship could be enhanced by making the service more widely available through the National Health Service (NHS). To understand the true impact of this service, a comparative study would need to be undertaken with a full health economic analysis. This concurs with NICE recommendations that suggest that randomized controlled trials should be undertaken to determine whether using POCT in decision making when prescribing antimicrobials is clinically and cost effective.3

Funding

Boots UK funded the service development and delivery.

A. P. R. W. was part supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Transparency declarations

T. T. and G. M. are employees of Boots UK and so conducted the evaluation as part of their usual employee functions. T. T. and G. M. do not hold any stock or options in Boots UK. P. H. and A. P. R. W. received no payment for conducting the evaluation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support and assistance of Boots UK.

References

- 1.Hawker JI, Smith S, Smith GE et al. Trends in antibiotic prescribing in primary care for clinical syndromes subject to national recommendations to reduce antibiotic resistance, UK 1995-2011: analysis of a large database of primary care consultations. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 3423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD et al. Antibiotic prescription strategies for acute sore throat: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antimicrobial Stewardship: Systems and Processes for Effective Antimicrobial Medicine Use. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng15.

- 4.Department of Health and Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/244058/20130902_UK_5_year_AMR_strategy.pdf.

- 5.Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, Galeone C et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18 Suppl 1: 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence J. Antibiotic use rising for coughs and colds. Pharmaceutical J 2014; 293: 169. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wellcome Trust. Exploring the Consumer Perspective on Antimicrobial Resistance. www.wellcome.ac.uk/stellent/groups/corporatesite/@policy_communications/documents/web_document/wtp059551.pdf (date last accessed, June 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNulty C, Joshi P, Butler CC et al. Have the public's expectations for antibiotics for acute uncomplicated respiratory tract infections changed since the H1N1 influenza pandemic? A qualitative interview and quantitative questionnaire study. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e000674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal College of General Practitioners. TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit. www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/toolkits/target-antibiotics-toolkit.aspx.

- 10.Proprietary Association of Great Britain. Making the Case for the Self Care of Minor Ailments. www.selfcareforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Minorailmentsresearch09.pdf.

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Respiratory Tract Infections - Antibiotic Prescribing. Prescribing of Antibiotics for Self-Limiting Respiratory Tract Infections in Adults and Children in Primary Care. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69. [PubMed]

- 12.MacLean LG, Schwartz C, Sclar DA et al. Community Pharmacy Based Rapid Strep Testing With Prescriptive Authority. Community Pharmacy Foundation; www.communitypharmacyfoundation.org/resources/grant_docs/CPFGrantDoc_12587.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klepser DG, Bisanz SE, Klepser ME. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-provided treatment of adult pharyngitis. Am J Manag Care 2012; 18: e145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worrall G, Hutchinson J, Sherman G et al. Diagnosing streptococcal sore throat in adults: randomized controlled trial of in-office aids. Can Fam Physician 2007; 53: 666–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aalbers J, O'Brien KK, Chan WS et al. Predicting streptococcal pharyngitis in adults in primary care: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs and validation of the Centor score. BMC Medicine 2011; 9: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PHE. Antibiotic Guardian. www.antibioticguardian.com.

- 17.Morgan O, Baker A. Measuring deprivation in England and Wales using 2001 Carstairs scores. Health Stat Q/ONS 2006: 28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Personal Social Services Research Unit. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2014. In: Curtis L, ed. Canterbury: The University of Kent, 2014. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2014/. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. www.who.int/drugresistance/global_action_plan/en/.

- 20.NHS England. Improving Health and Patient Care Through Community Pharmacy - A Call to Action. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/community-pharmacy-cta.pdf.

- 21.Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Participatory medicine: a home score for streptococcal pharyngitis enabled by real-time biosurveillance: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159: 577–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llor C, Madurell J, Balague-Corbella M et al. Impact on antibiotic prescription of rapid antigen detection testing in acute pharyngitis in adults: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: e244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little P, Hobbs FD, Mant D et al. Incidence and clinical variables associated with streptococcal throat infections: a prospective diagnostic cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62: e787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little P, Hobbs FD, Moore M et al. Clinical score and rapid antigen detection test to guide antibiotic use for sore throats: randomised controlled trial of PRISM (primary care streptococcal management). BMJ 2013; 347: f5806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little P, Hobbs FD, Moore M et al. PRImary care Streptococcal Management (PRISM) study: in vitro study, diagnostic cohorts and a pragmatic adaptive randomised controlled trial with nested qualitative study and cost-effectiveness study. Health Technol Assess 2014; 18: vii-xxv, 1–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PHE. Management of Infection Guidance for Primary Care for Consultation and Local Adaptation. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507191/Managing_Common_Infections.pdf.

- 27.Bjerrum L, Cordoba Currea GC, Llor C et al. Lower threshold for rapid antigen detection testing in patients with sore throats would reduce antibiotic use. BMJ 2013; 347: f7055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiappini E, Regoli M, Bonsignori F et al. Analysis of different recommendations from international guidelines for the management of acute pharyngitis in adults and children. Clin Ther 2011; 33: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snow V, Mottur-Pilson C, Cooper RJ et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 506–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]