Abstract

Background:

Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2 (APS-2), also known as Schmidt's syndrome, is an uncommon disorder characterized by the coexistence of Addison's disease with thyroid autoimmune disease and/or type 1 diabetes mellitus. Addison's disease as the obligatory component is potentially life-threatening. Unfortunately, the delayed diagnosis of Addison's disease is common owing to its rarity and the nonspecific clinical manifestation.

Methods:

Here we reported a case of 38-year-old female patient who presented with 2 years’ history of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and received levothyroxine replacement. One year later, skin hyperpigmentation, fatigue, loss of appetite, and muscle soreness occurred. She was advised to increase the dose of levothyroxine, but the symptoms were not relieved. After 4 months, the patient accompanied with dizziness, nausea, nonbloody vomiting, and fever. However, she was diagnosed with acute gastroenteritis and fell into shock and ventricular fibrillation subsequently. Further evaluation in our hospital revealed elevated adrenocorticotrophic hormone and low morning serum cortisol, associated with hyponatremia and atrophic adrenal gland. Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism and Hashimoto's thyroiditis were also demonstrated.

Results:

After the supplementation with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone was initiated, the physical discomforts were alleviated and plasma electrolytes were back to normal.

Conclusion:

The uncommon case involving 3 endocrine organs reinforced the significance of a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment of APS-2, and physicians needed to sharpen their awareness of the potentially life-threatening disease.

Keywords: Addison's disease, adrenal crisis, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2, case report

1. Introduction

Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (APS) are a group of diseases characterized by the combination of >1 organ-specific autoimmune disorders affecting both endocrine and nonendocrine organs.[1] APS were mainly classified into 4 types.[2] Type 2 APS (APS-2), also known as Schmidt's syndrome, is much more common and defined by the coexistence of Addison's disease with thyroid autoimmune disease and/or type 1 diabetes mellitus.[3] Addison's disease as the obligatory component is potentially life-threatening. However, due to its rarity and the nonspecific clinical manifestation, the diagnosis of Addison's disease still remained challenging and often delayed by many months or years. Here, we reported a case of APS-2 with an uncommon condition involved 3 endocrine organs (thyroid, adrenal, and ovarian), and it was also rare that chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis preceding the occurrence of primary adrenal insufficiency. Furthermore, acute adrenal crisis occurred in the patient because of misdiagnosis.

2. Case presentation

2.1. Patient

A 38-year-old female patient had been diagnosed with Hashimoto's thyroiditis on routine healthy examination since 2 years, and treated with levothyroxine with 25 μg daily. Approximately 1 year before the admission, when skin hyperpigmentation, fatigue, loss of appetite, and muscle soreness occurred. Due to these symptoms worsened progressively, the patient attended to a rural hospital and was advised to continue taking levothyroxine with 50 μg daily. The suffering was not relieved. Four months later, the patient presented with dizziness, nausea, nonbloody vomiting, and fever without inducing factors. She self-administered antibiotics and acetaminophen, without improvement. Then, she was referred to a gastroenterology department of another hospital. Laboratory tests revealed hyponatremia (125.8 mmol/L), relatively higher plasma potassium (5.36 mmol/L) and lower plasma glucose level (3.56 mmol/L). Thyroid function tests showed primary hypothyroidism. Acute gastroenteritis was considered, and upper and lower endoscopic examinations were performed. However, the results were reportedly normal. The patient received levothyroxine, rehydration, nutritional support, and antibiotics treatment, but both nausea and vomiting persisted. One day after endoscopic examinations, the patient presented with fainting, diaphoresis, ashen skin and hypotension with 62/42 mm Hg, and ventricular fibrillation happened soon. She was immediately admitted to the intensive care unit of the hospital. Combined with signs, symptoms, and past history, the diagnosis of Addison's disease was suspected. Therapy with cardiac electric defibrillation, fluid resuscitation, dopamine and intravenous hydrocortisone begun, then to oral prednisone. The patient's symptoms and laboratory test results markedly improved within 1 week. For further evaluation and treatment, she was discharged with instructions to be seen in the endocrinology department in our hospital. No fluctuating skeletal muscle weakness, asymptomatic depigmented macules, and alopecia were observed in the patient. Menstrual history showed irregular menstrual cycles and oligomenorrhea accompanied by loss of axillary and public hair during the last 3 years. The menstrual-cycle length ranged from 2 to 4 months, and the menstruation lasted 2 to 3 days. Previously, menstrual cycles were regular, and she had given birth to a daughter.

2.2. Physical exam

On physical examination, the patients had generalized hyperpigmentation, especially in mucous membranes, pressure points, and palmar creases. Her blood pressure was 120/78 mm Hg, and grade 1 diffuse goiter in thyroid examination.

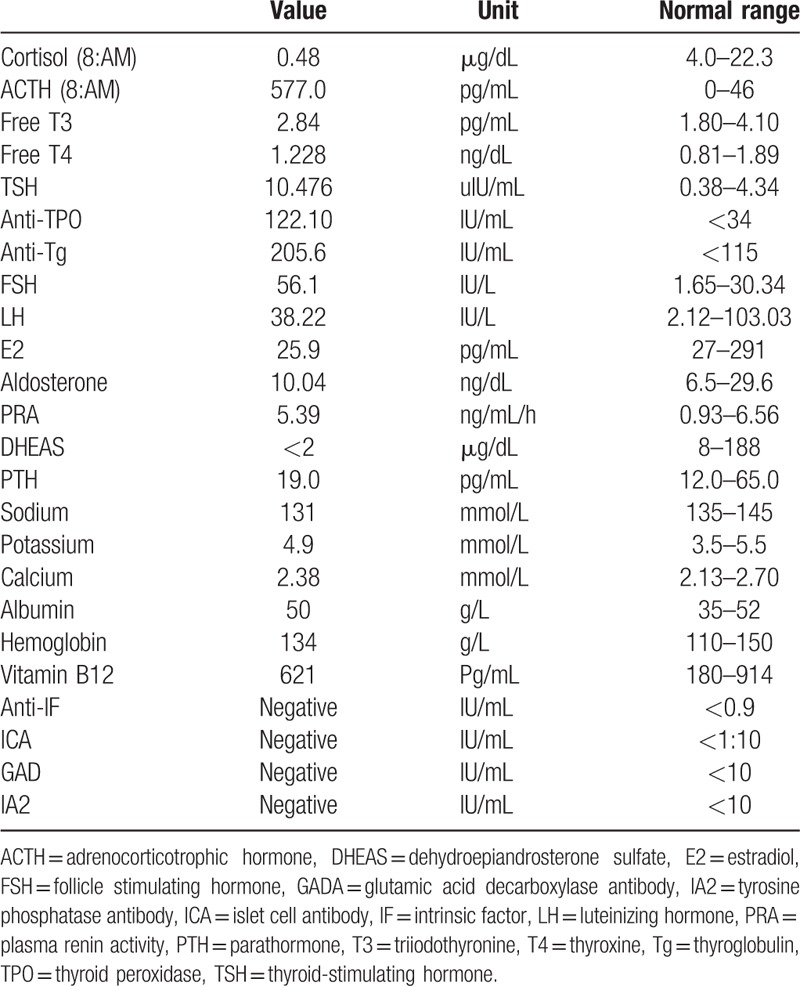

2.3. Laboratory testing

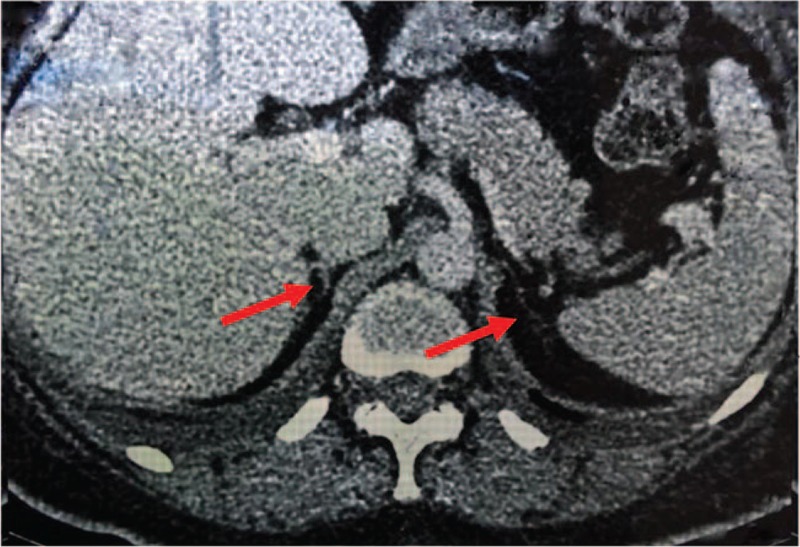

The biochemical test revealed the reduced level of serum sodium. The elevated adrenocorticotrophic hormone and low morning serum cortisol, associated with relatively higher plasma renin activity, lower aldosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels were consistent with primary adrenal insufficiency (Table 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans of abdomen demonstrated remaining atrophic adrenal glands (Fig. 1). The thyroid function test showed positive anti-thyroglobulin (A-Tg) and anti-thyroperoxidase (A-TPO) antibodies with increased thyroid-stimulating hormone. Gonadal hormone determination was suggestive of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Plasma potassium, calcium, phosphorus, hemoglobin, Vitamin B12 and parathormone, as well as the results of oral glucose tolerance test were all within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, intrinsic factor antibody and islet-specific autoantibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), islet cell (ICA), and tyrosine phosphatase (IA2) were negative (Table 1). Bone mineral density measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry suggested osteopenia of femoral neck with Z score –1.0.

Table 1.

Laboratory values during inpatient evaluation.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography imaging of the adrenal glands. The arrows showed the remaining atrophic adrenal glands.

2.4. Interventions

The patient was administered with hydrocortisone (10 mg orally in the morning, 5 mg at noon, 5 mg in the evening) and levothyroxine (75 μg orally once daily). The increased PRA and decreased aldosterone suggested the deficiency of mineralocorticoids, and the supplementation with fludrocortisone (0.1 mg orally once daily) was initiated. She was discharged with normal plasma electrolytes and blood pressure, and all the physical discomforts were alleviated. Physicians also educated the patient on how to self-adjust the steroids doses under stress situation.

3. Discussion

In 1926, Schmidt first described 2 patients who presented with Addison's disease concurrently with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis.[4] After his report, Schmidt's syndrome was termed as the combined occurrence of Addison's disease and autoimmune thyroid disease. Subsequently, the association between type 1 diabetes mellitus and Addison's disease was confirmed. The defining component of APS-2 is Addison's disease in combination with either autoimmune thyroid disease (including Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ disease) and/or type 1 diabetes mellitus. Other autoimmune diseases less commonly related to APS-2 include hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, celiac disease, vitiligo, pernicious anemia, myasthenia gravis, chronic atrophic gastritis, alopecia, and stiff man syndrome.[3]

The estimated prevalence of APS-2 is ∼1.4 to 4.5 per 100,000 inhabitants. APS-2 generally has its onset in adulthood, mostly at ages 20 to 60 years. Women are affected more frequently than men with a 3:1 ratio.[5–7] In contrast to APS-1, which is a recessive disorder caused by AIRE gene mutation, APS-2 is a complex polygenetic disease associated with HLA-DR3, HLA-DR4, and non-HLA genes, as well as environmental factors. APS-2 often exhibits familial aggregation.[3,7]

Our patient was a middle-aged woman and just at the age of peak incidence of APS-2. The coexistence of Addison's disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and primary ovarian insufficiency in the patients was in accord with the diagnosis of APS-2. Despite ∼50% patients with autoimmune adrenal insufficiency have additional associated autoimmune disease and autoimmune thyroid disease is the most common, only 1% patients with autoimmune thyroid disease will develop adrenal disease.[8,9] The index case initially presented with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and the involvement of adrenal occurred 1-year later. On account of atypical clinical manifestations with fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting, the patient was misdiagnosed with an acute gastroenteritis leading to adrenal crisis. One possible explanation for the occurrence of adrenal crisis was that continued replacement of levothyroxine prior to identification of concurrent Addison's disease precipitated the adrenal crisis. Levothyroxine enhances corticosteroid metabolism in liver. On the other hand, gastrointestinal preparation for endoscopic examinations probably aggravated the water and electrolyte homeostasis inducing adrenal crisis.

Unfortunately, the delayed diagnosis of Addison's disease is still common. According to a cross-sectional investigation in 216 patients with adrenal insufficiency, <50% of patients were correctly diagnosed within first half year after symptoms appeared, and it took >5 years until being diagnosed for 20% patients.[10] Psychiatry and gastroenterology were the main origin causing the delay of diagnosis.[11] Furthermore, the latency between first symptoms and diagnosis was demonstrated as the most important factors that influenced the patients’ quality of life.[12] Actually, when a single component disease of APS-2 occurred, there was a higher probability that another associated disease would develop than the general population.[13] Thus, it is essential for physicians to maintain a high clinical suspicion for the existence of other autoimmune disorders in all patients with 1 autoimmune disease. In particular, since Addison's disease is an uncommon, potentially fatal disorder, and the onset of symptoms is often nonspecific, similar to a gastrointestinal or psychiatric disease, prompt recognition of the disease and early treatment is vital. The consensus statement for the management of Addison's disease from European experts recommended that for all patients with unexplained collapse, hypotension, vomiting or diarrhea, the diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency should be considered.[14]

Although the sequence and the time interval between the clinical appearance of different autoimmune disorders of APS-2 varies considerably, the circulating associated autoantibodies can precede the clinically evident manifestations for months or years.[9] Therefore, once an autoimmune disease was identified, the early screening for antibodies against associated disease such as A-Tg, A-TPO, GADA, ICA, and antibodies to 21-hydroxylase was crucial, which facilitated the diagnosis of further disorder at an early stage.[13] For our case, after the diagnosis of APS-2 was made, the further extensive screening for antibodies was performed, and all were negative. Besides, a study of 10 families with APS-2 found that 1 out of 7 relatives had an undiagnosed autoimmune disease, the most common being autoimmune thyroid disease.[15] Therefore, relatives of patients with APS-2 also need to be monitored closely albeit the optimal screening interval is not defined.[3]

In addition, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism was demonstrated in this case. She presented with a sustained oligomenorrhea history, accompanied by menopausal FSH levels and decreased estrogen levels lower than 50 pg/mL for >4 months before the age of 40 years. The diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) can be made.[16] In view of antithyroid autoantibodies positive and the coexistence of Addison's disease, ovarian destruction was first considered as an autoimmune origin. Autoimmunity only accounted for 5% patients with POI,[17] and autoimmune POI was strongly associated with Addison's disease. A study in a large cohort of Italian females with Addison's disease revealed that about 20% was diagnosed with POI, and the lowest prevalence of POI was detected in patients with APS-2.[18] The POI onset in APS-2 usually precedes Addison's disease, and the tendency was observed in our case as well. A growing body of evidence indicated that antibodies to steroid-producing cells (StCA), 17α-hydroxylase (17α-OH), and to P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc) were good markers of POI in patients with APS-2.[18,19] The 3 types of antibodies were detectable in the majority of these patients, and there was a higher possibility for antibody-positive (StCA, 17α-OHAb, and/or P450sccAb) patients to develop clinical POI in the later follow-up time.[20,21] Unfortunately, these antibodies were not measured in our case. Besides, osteopenia was observed in the case, and the possible cause was hypogonadism and Vitamin D deficiency (15.1 ng/mL). Calcium and Vitamin D were administered. Given that the index patient suffered from the shock lately and the duration of hydrocortisone replacement was short, we did not initiate hormone therapy. Corticosteroid may restore ovarian function. At the 3 months visit, the patient's menstrual cycles had returned to regular, and the serum FSH (10.75 mIU/mL) and E2 (242.0 pg/mL) levels were also back to normal.

In summary, autoimmune thyroid disease is particularly common, and individuals with the only disorder are at very low risk for the development of a second autoimmune disease. However, even so, when the patients presented with ill-defined weakness or fatigue, the underlying diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency should be highly suspected in order to minimize the occurrence of acute adrenal crisis. Screening for organ-specific autoantibodies of patients and relatives is also valuable. Furthermore, keep in mind that thyroid hormone replacement should not be administered until glucocorticoids initiated, because TSH increases when glucocorticoids are reduced and it may normalize after adrenal substitutive therapy. The limitations stem mainly from the lack of detection for antibodies to 21-hydroxylase and steroid-producing cells.

Herein, we reported an uncommom case who had the complete tri-glandular syndrome and experienced adrenal crisis owing to misdiagnosis. The case reinforced the significance of a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment of APS-2, and physicians needed to sharpen their awareness of the potentially life-threatening disease. Early identification and treatment of APS-2 contribute to reduce the mortality and enhance the quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient for participating in this case study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 17α-OH = 17α-hydroxylase, APS = autoimmune polyglandular syndromes, A-Tg = anti-thyroglobulin, A-TPO = anti-thyroperoxidase, GADA = glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody, IA2 = tyrosine phosphatase antibody, ICA = islet cell antibody, P450scc = P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme, POI = primary ovarian insufficiency, StCA = steroid-producing cells antibody.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2068–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neufeld M, Blizzard RM. Pinchera A, Doniach D, Fenzi GF, Baschieri L. Polyglandular autoimmune disease. Symposium on Autoimmune Aspects of Endocrine Disorders.. New York: Academic Press; 1980. 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michels AW, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010; 6:270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt MB. Eine biglandulare Erkrankung (Nebennieren und Schild-drüse) bei Morbus Addisonii. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol 1926; 21:212–221. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betterle C, Dal Pra C, Mantero F, et al. Autoimmune adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes: autoantibodies, autoantigens, and their applicability in diagnosis and disease prediction. Endocr Rev 2002; 23:327–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schatz DA, Winter WE. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. II: clinical syndrome and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2002; 31:339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betterle C, Lazzarotto F, Presotto F. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome Type 2: the tip of an iceberg? Clin Exp Immunol 2004; 137:225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betterle C, Volpato M, Rees Smith B, et al. Adrenal cortex and steroid 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies in adult patients with organ-specific autoimmune diseases: markers of low progression to clinical Addison's disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82:932–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michels AW, Eisenbarth GS. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS-1) as a model for understanding autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 2 (APS-2). J Intern Med 2009; 265:530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleicken B, Hahner S, Ventz M, et al. Delayed diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is common: a cross-sectional study in 216 patients. Am J Med Sci 2010; 339:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ten S, New M, Maclaren N. Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86:2909–2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer G, Hackemann A, Penna-Martinez M, et al. What affects the quality of life in autoimmune Addison's disease? Horm Metab Res 2013; 45:92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutolo M. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. Autoimmun Rev 2014; 13:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husebye ES, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Consensus statement on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with primary adrenal insufficiency. J Intern Med 2014; 275:104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenbarth GS, Wilson PW, Ward F, et al. The polyglandular failure syndrome: disease inheritance, HLA type, and immune function. Ann Intern Med 1979; 91:528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shelling AN. Premature ovarian failure. Reproduction 2010; 140:633–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Marca A, Brozzetti A, Sighinolfi G, et al. Primary ovarian insufficiency: autoimmune causes. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2010; 22:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reato G, Morlin L, Chen S, et al. Premature ovarian failure in patients with autoimmune Addison's disease: clinical, genetic, and immunological evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96:E1255–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahonen P, Miettinen A, Perheentupa J. Adrenal and steroidal cell antibodies in patients with autoimmune polyglandular disease type I and risk of adrenocortical and ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987; 64:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dal Pra C, Chen S, Furmaniak J, et al. Autoantibodies to steroidogenic enzymes in patients with premature ovarian failure with and without Addison's disease. Eur J Endocrinol 2003; 148:565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falorni A, Laureti S, Candeloro P, et al. Steroid-cell autoantibodies are preferentially expressed in women with premature ovarian failure who have adrenal autoimmunity. Fertil Steril 2002; 78:270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]