Abstract

Background:

Umbilical cord hemangioma is very rare and may not be detected prenatally. However, it should be considered in differential diagnosis with other umbilical masses because it can cause significant morbidity.

Methods:

We report the case of a newborn referred with suspected omphalitis and umbilical hernia.

Results:

Physical examination showed an irreducible umbilical tumor, the size of olive, with dubious secretion. The initial suspected diagnosis was urachal or omphalomesenteric duct remnants. Abdominal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging showed an umbilical and a mesenteric mass. Tumor markers were negative. A definitive diagnosis of umbilical cord and intestinal hemangioma was established after surgical excision and histologic examination of the umbilical mass. Propranolol was prescribed due to the extent of the intestinal lesion.

Conclusion:

This report highlights the diagnostic challenges of hemangiomas in unusual locations. Apart from the rarity of these tumors, few tests are available to guide diagnosis, and surgery and histologic examination are generally required for a definitive diagnosis. Finally, it is essential to rule out associated malformations and hemangiomas in other locations.

Keywords: gastrointestinal hemangioma, mesenteric mass, propranolol treatment, umbilical cord hemangioma

1. Introduction

Hemangiomas are benign endothelial cell neoplasms that preferentially affect the skin, although they are found in many organs. They occur as isolated lesions or as multiple lesions with extensive cutaneous involvement or diffuse involvement affecting the skin and other organs, as diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis. Hemangiomas may also form part of a syndrome or occur in association with other malformations.

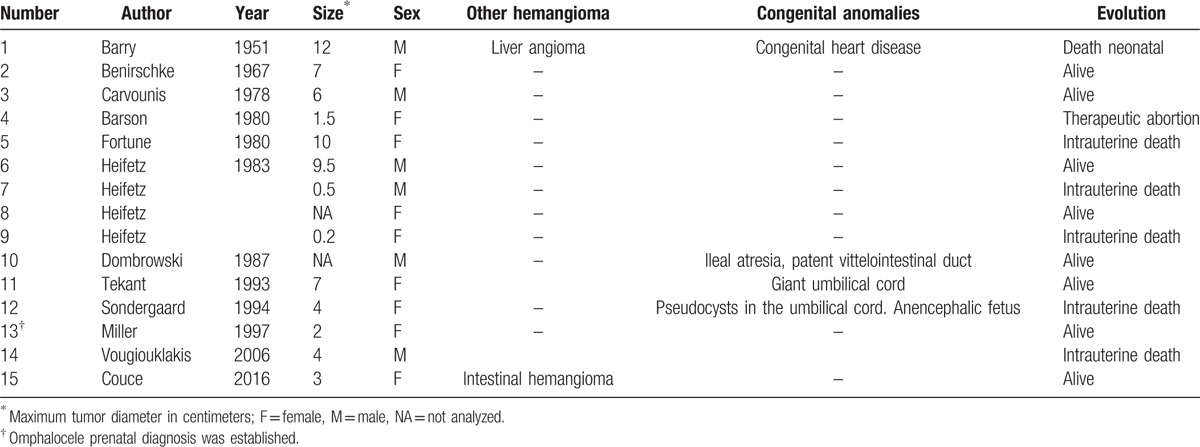

Several hundred cases of placental hemangioma have already been described, but umbilical cord hemangioma is an extremely rare tumor arising from endothelial cells of the umbilical vessels and the umbilical arteries in particular. In a PubMed search of the literature from 1951, 44 cases have been reported to date, and the tumor is identified prenatally in over 80% of cases and presents as a fusiform swelling in the cord.[1–3] This swelling corresponds to an angiomatous nodule surrounded by edema of the Wharton jelly with a diameter of between 0.2 and 18 cm. Microscopic examination typically shows capillaries embedded in myxoid stroma. Only 14 cases were detected after delivery,[4–14] 7 of them as part of the post mortem investigation,[4,7–9,12,14] (Table 1). Reported associations include increased alpha-fetoprotein levels, hydramnios, fetal hydrops, and cord hemangiomas are assumed to increase the risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity. Early diagnosis and treatment is essential.

Table 1.

Umbilical cord hemangioma diagnosed in the neonatal period.

The case presented here is of an umbilical cord hemangioma diagnosed in neonatal period, which was mimicking other initially diagnosis. For publishing, informed consent was obtained by the parents and no other ethical accuracies were necessary.

2. Case report

A 12-day-old full-term female infant born by vaginal delivery after an uneventful pregnancy was referred to our hospital with a suspected diagnosis of omphalitis and umbilical hernia. The parents reported a dilated umbilical cord base at its insertion into the abdomen. The umbilical cord stump had not yet fallen off (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cord umbilical hemangioma when umbilical cord stump had not yet fallen off.

It was the first pregnancy of a 30-year-old mother and prenatal ultrasound (US) and other examinations had been normal. The infant had an Apgar score of 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The mother had no toxic habits (drugs, alcohol, tobacco, or drugs). Newborn metabolic screening was normal and the infant was breastfed.

On admission to our unit, the patient was found to be asymptomatic. Her abdomen was soft and nondistended and palpation did not elicit pain. There were no palpable masses. After the umbilical cord stump had fallen off the next day, we observed a pink, rubbery irreducible umbilical mass measuring 3 × 2 cm with the umbilical vessels displaced toward the bottom but contained therein. There was a dubious hole and secretion in the center of the mass (Fig. 2). The surrounding umbilical skin was not erythematous and no foul odors were noted. The suspected clinical diagnosis at this stage was urachal or omphalomesenteric duct remnants.

Figure 2.

(A) Appearance of the umbilical mass before resection. (B) Surgical specimen. Center: umbilical mass. Top left: umbilical vein. Bottom right: right umbilical artery and aneurysm. Bottom left: left umbilical artery. Bottom center: urachus.

US of the umbilical cord showed a solid hyperechogenic mass, and examination of blood flow with color Doppler imaging showed intense flow with interruption in the anterior abdominal wall and an apparent connection to the dome of the urinary bladder. These findings supported the diagnosis of an urachal cyst. Abdominal US showed a hypervascular solid mass with hyperechoic areas on the left flank and medial extension across the midline. The initial question was whether the umbilical and intestinal masses might be related or whether they were 2 independent processes.

Evaluation of tumor markers for the differential diagnosis of abdominal masses showed unremarkable findings for urinary catecholamines, alpha-fetoprotein, neuron-specific enolase, and human chorionic gonadotropin. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the presence of a mesenteric mass in the left flank, with prominent vascularization; the mass was hyperintense on T2-weighted images and hypointense on T1-weighted images. A solid umbilical mass, with a similar appearance, was observed, but there was no continuity with the bladder dome or the abdominal mass (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance image showing umbilical and abdominal masses. The umbilical mass appears to be in contact with the bladder, but it is not continuous with the abdominal component.

It was decided to surgically remove the umbilical mass and perform an exploratory laparotomy. The mass showed no intra-abdominal continuity and contained the umbilical vein, 2 umbilical arteries, and the obliterated urachus. The right umbilical artery showed vascular abnormalities consistent with aneurysmatic dilatation and tortuosity. In the abdomen, we detected a vascular malformation in the territory supplied by the superior mesenteric artery, the mesentery extending from the jejunum to the distal ileum and the transverse colon wall were affected (Fig. 4). Histologically, the lesions were consistent with hemangiomas. The immunohistochemical study was positive for GLUT-1 and D2–40 and negative for WT-1.

Figure 4.

Morphologic appearance of the visceral hemangioma.

There was no evidence of platelet sequestration or hyperdynamic state. Echocardiography, US examination of the brain, eye examination, and thoracic MRI were normal.

The patient was treated with oral propranolol at a dosage of 2 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses, and no adverse effects were observed. She was discharged for medical follow-up. US imaging of intestinal hemangioma after 6 months of propranolol treatment showed a decrease in the caliber of vessels and distal vessels are not accentuated.

3. Discussion

Umbilical cord hemangiomas are extremely rare. The differential diagnosis includes hematomas, varicose veins, aneurysms, thrombosis, hernia into the cord, abdominal wall defects, omphalomesenteric duct cysts, allantoic cysts, and tumors such as teratoma and metastatic neuroblastoma.[15] Diagnosis by direct visualization and imaging studies can be difficult. In our patient, for example, the initial diagnosis contemplated was urachal or omphalomesenteric remnants. Associated cord edema is a nearly constant finding in umbilical cord hemangiomas.[2] These tumors typically occur as an isolated anomaly, although they have been described in association with other malformations, such as heart malformations, anencephaly, skin malformations, various syndromes, and, like in our case, cutaneous/systemic hemangiomas.[16,17] They have been associated with a mortality rate of 35%; the main causes of death are bleeding and umbilical cord torsion.[10,17]

Gastrointestinal hemangiomas are rare and account for just 0.05% of all intestinal neoplasms; they are more common in the small intestine, and the jejunum is the most frequently affected segment. Our case is particularly interesting, as there have been few reports of involvement of the mesentery and the transverse colon,[16] and to the knowledge of the authors, this is the first report showing association of umbilical cord and intestinal hemangiomas detected in the neonatal period. Preoperative diagnosis of a mesenteric hemangioma is virtually impossible although abdominal imaging can help to locate and visualize the lesion. Manifestations and symptoms vary according to location. The most common presenting symptom is gastrointestinal bleeding, followed by obstruction or intussusception.[18]

Treatment varies with the type of lesion, location, extent of involvement, symptoms, and general operability. Expectant management only may be indicated in small hemangiomas, located far from areas of possible functional damage and slow-growing. Hemangiomas that can cause functional impairment, fast-growing hemangiomas, disseminated cutaneous hemangiomas, and visceral hemangiomas that can lead to heart failure, severe bleeding, or coagulation disorders must be treated. Patients with gastrointestinal hemangiomas located in a short well-defined intestinal segment are therefore usually candidates for surgical resection. Other treatments for nonresectable or diffuse hemangiomas include radiation therapy, cryotherapy, brachytherapy, sclerotherapy, arterial embolization (with limited success), and pharmacologic treatment. The use of multiple treatments can be explained by our limited knowledge of the biology of hemangiomas.[19] The traditional drugs of choice were corticosteroids and drugs such as thalidomide and somatostatin but propranolol is now the first-line treatment for problematic proliferating hemangiomas.[20] In our patient, we initiated propranolol treatment because of the extent of the lesion and the potential risk of serious complications, and the response was favorable.

4. Conclusions

In summary, although umbilical cord hemangiomas are rare and are usually identified prenatally, clinicians should understand their clinical significance and include these tumors in the differential diagnosis of an umbilical mass in a newborn. A thorough physical examination and complementary studies are necessary to evaluate associated anomalies, including cutaneous and systemic hemangiomas and other malformations. Diagnosis of umbilical cord or abdominal masses is challenging and a definitive diagnosis usually requires surgery and histopathologic examination. Finally, clinicians should be aware that despite their benign nature, intestinal hemangiomas can lead to a fatal outcome in cases of delayed diagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, US = ultrasound.

Funding: Article-processing charge was covered by the Fundación Ramón Dominguez-C012.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Matsuda S, Sato Y, Marutsuka K, et al. Hemangioma of the umbilical cord with pseudocyst. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2011; 30:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghidini A, Romero R, Eisen RN, et al. Umbilical cord hemangioma. Prenatal identification and review of the literature. J Ultrasound Med 1990; 9:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadopoulos VG, Kourea HP, Adonakis GL, et al. A case of umbilical cord hemangioma: Doppler studies and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009; 144:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry FE, McCoy CP, Callahan WP. Hemangioma of the umbilical cord. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1951; 62:675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benirschke K, Dodds J. Angiomyxoma of the umbilical cord with atrophy of an umbilical artery. Obstet Gynecol 1967; 30:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvounis E, Dimmick J, Wright V. Angiomyxoma of the umbilical cord. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1978; 102:178–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barson AJ, Donnai P, Ferguson A, et al. Haemangioma of the cord: further cause of raised maternal serum and liquor alpha-fetoprotein. Br Med J 1980; 281:1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fortune DW, Ostor A. Angiomyxomas of the umbilical cord. Obstet Gynecol 1980; 55:375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heifetz SA, Rueda-Pedraza ME. Hemangiomas of the umbilical cord. Pediatr Pathol 1983; 1:385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dombrowski MP, Budev H, Wolfe HM, et al. Fetal hemorrhage from umbilical cord hemangioma. Obstet Gynecol 1987; 70:439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tekant G, Kasabaligil A, Abbasoglu L, et al. Giant umbilical cord associated with cord hemangioma. Pediatr Surg Int 1993; 8:82–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sondergaard G. Hemangioma of the umbilical cord. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1994; 73:434–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller KA, Gauderer MW. Hemangioma of the umbilical cord mimicking an omphalocele. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32:810–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vougiouklakis T, Mitselou A, Zikopoulos K, et al. Ruptured hemangioma of the umbilical cord and intrauterine fetal death, with review data. Pathol Res Pract 2006; 202:537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natalucci G, Wisser J, Weil R, et al. Your diagnosis? Umbilical cord tumor. Eur J Pediatr 2007; 166:753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz AR, Ginsberg AL. Giant Mesenteric Hemangioma with small intestinal involvement. Dig Dis Sci 1999; 44:2545–2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardarella A, Buccoliero AM, Taddei A, et al. Hemangioma of the umbilical cord: report of a case. Pathol Res Pract 2003; 199:51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soukoulis IW, Liang MG, Fox VL, et al. Gastrointestinal infantile hemangioma: presentation and management. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015; 61:415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smulian JC, Sarno AP, Rochon ML, et al. The natural history of an umbilical cord hemangioma. J Clin Ultrasound 2016; 44:455–458.Epub Feb 22. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanlander A, Decaluwe W, Vandelanotte M, et al. Propranolol as a novel treatment for congenital visceral haemangioma. Neonatology 2010; 98:229–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]