Graphical abstract

Keywords: Adansonia digitata, Biosorbent, Potentially toxic metal, Nitrilotriacetic acid, Wastewater, XRD

Abstract

Nitrilotriacetic acid functionalized Adansonia digitata (NFAD) biosorbent has been synthesized using a simple and novel method. NFAD was characterized by X-ray Diffraction analysis technique (XRD), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area analyzer, Fourier Transform Infrared spectrometer (FTIR), particle size dispersion, zeta potential, elemental analysis (CHNS/O analyzer), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), differential thermal analysis (DTA), derivative thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The ability of NFAD as biosorbent was evaluated for the removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions from aqueous solutions. The particle distribution of NFAD was found to be monomodal while SEM revealed the surface to be heterogeneous. The adsorption capacity of NFAD toward Pb (II) ions was 54.417 mg/g while that of Cu (II) ions was found to be 9.349 mg/g. The adsorption of these metals was found to be monolayer, second-order-kinetic, and controlled by both intra-particle diffusion and liquid film diffusion. The results of this study were compared better than some reported biosorbents in the literature. The current study has revealed NFAD to be an effective biosorbent for the removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) from aqueous solution.

Introduction

Water is essential for life and it is desired to be safe, potable, appealing to all life on earth and should be free of pollutants that are harmful to human, animal, and the environment. In spite of the vast majority of water bodies available in the world, clean water is not easily accessible or readily available in most parts of the globe most especially in the developing nations.

Potentially toxic metals such as copper (Cu) and lead (Pb) have been identified as pollutants found in water. Potentially toxic metal contamination in aquatic environment has attracted global attention due to its environmental and health risks, toxicity, abundance, and persistence [1], [2]. Cu and Pb are capable of reaching aquatic environment through anthropogenic processes like fumes from paint, scrap from old batteries, cable sheathing, ceramic ware, and renovations resulting in dust [3]. The presence of potentially toxic metals has been reported in rivers, streams, ground water, and surface water as a result of global industrialization, rapid population growth, agricultural production, and intensive domestic activities [4]. The treatment of these generated domestic and industrial wastes has been of concern as most of these wastes are not properly treated before being discharged or discarded into the environment. This action has always resulted in pollution of water bodies present in such environment and ultimately leading to increase in the level of potentially toxic metals in the environment as these metals can bioaccumulate over a period of time. These potentially toxic metals are toxic to human, animal, and the environment most especially when humans and animals drink from such polluted water sources. Cu and Pb are harmful as they can accumulate in living organisms; they are non-biodegradable and are capable of causing various diseases and disorders.

Several approaches have been employed for the removal of potentially toxic metal ions from wastewater. Some of these include chemical precipitation, ion-exchange, electrodialysis, flocculation, solvent extraction, coagulation, photocatalysis, membrane separation, and adsorption [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Of these, adsorption method is one of the most popular and effective processes for removing toxic heavy metal from polluted water due to its flexibility in design and operation [5]. Research attentions have been focused on the search for environmentally friendly low-cost biomass adsorbents that have good metal binding capacities. Some biomasses have been identified in this regards but the adsorption capacity and selectivity of some of them need to be improved on [2], [5]. So, it is important to develop cheap and eco-friendly adsorbents with high metal removal, excellent selectivity, and fast process kinetics.

Several methods, such as nitration, acid and alkali modification, oxidation, and chemical grafting, have been used to enhance the adsorption performance of some biomass [10], [11] but the results have shown that a number of them are either expensive or with low selectivity and sometimes may not be suitable for industrial wastewater which may be highly concentrated with these potentially toxic metals. It is important to develop low-cost adsorbents that will be efficient with sufficient capacity in treating this highly polluted industrial wastewater before they are discharged into the environment. Previously reported works have shown that biomass has the capacity of removing potentially toxic metals from aqueous solution but mostly at a capacity which may require enhancement [11]. Pehlivan et al. [12] reported a capacity of 4.64 mg/g for Cu (II) ions using barley straw while Alhakawati and Banks [13] reported 2.35 mg/g for sea weed. Several other biomasses such as orange peel [14], rice husk [15], natural bentonite [16], Eichornia Crassipes [17] and coconut shell [18] had also been used for the removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution with indications that these biomasses would have performed better if modified.

Nitrilotriacetic acid is an aminopolycarboxylic acid with high propensity of being able to use its carboxyl functional group in chelating metals. It also has an amine group on the molecular chain which may also exhibit strong adsorption ability for potentially toxic metals. With its pH range and functional groups, nitrilotriacetic compound should be able to bind with potentially toxic metal ions (such as Cu (II) and Pb (II)) through complexation or electrostatic interaction. In adsorption technology, surface functionalization has been proven to be effective [19]. In this context, the use of nitrilotriacetic acid in surface functionalization of a cheap underutilized biomass such as Adansonia digitata may be an economic viable means of tackling this need. A. digitata is an underutilized plant in Nigeria which belongs to the Bombacaceae plant family. Presently, the seed has no specific use in Nigeria and most times, it is discarded as waste. The seed is underutilized and chemical evaluation of the seed has shown it to be rich in some essential amino acids [20], [21]. It is non-toxic, cheap, readily available, and biodegradable [20].

Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate the possibility of using nitrilotriacetic acid-functionalized A. digitata seed as a low-cost biosorbent for the purification of waste and polluted water. Thus, in this study, A. digitata seed from Nigeria was chemically modified with nitrilotriacetic acid, and used for the removal of Cu (II) and Pb (II) ions from water system. The effects of adsorbent weight, change in temperature, pH, contact time, and initial concentration of Cu (II) and Pb (II) on the removal of adsorbates from the aqueous solution by the modified A. digitata seed were investigated as well as the mechanism of uptake of these heavy metal ions.

Material and methods

Materials

A. digitata seed used was obtained from the Botanical garden at the University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria. The A. digitata seed was ground in an industrial mill and extracted with n-hexane as previously described by Adewuyi et al. [22] and this was air dried and stored in an airtight container.

Lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2) and copper sulfate (Cu(SO4)·5H2O) salts were used in the preparation of the salt solutions. Stock solutions of 1000 mg/L were prepared by dissolving the accurately weighed amounts of Pb(NO3)2 and (Cu(SO4)·5H2O) in 1000 mL millipore water. Experimental solutions were prepared by diluting the stock solution with millipore water. Sodium chlorite, glacial acetic acid, NaOH, nitrilotriacetic acid and all other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Belo Horizonte, Brazil).

Preparation of nitrilotriacetic acid-functionalized A. digitata adsorbent

After the extraction of A. digitata seed with n-hexane, hemicellulose and lignin were partially removed from the seed without completely converting the seed to cellulose. This was to remove lignin, which could find its way into water during treatment and also to make the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the seed much more available for reaction with nitrilotriacetic acid.

To remove the lignin, the seed was treated with 0.7% (m/v) sodium chlorite solution at 60 °C for 2 h with continuous stirring using a Fisatom mechanical stirrer. This was filtered, washed severally with millipore water and finally placed in 2% (m/v) sodium bisulfite solution. The residue was filtered, washed, and dried in an oven until constant weight was obtained. The dried mass was then treated with alkali (17.5% NaOH, m/v) for 2 h to remove hemicelluloses; this was filtered, washed severally with millipore water and oven dried at 50 °C to obtain a light brown solid, pretreated A. digitata seed (ADC). Nitrilotriacetic acid was finally imprinted on the surface of ADC by simple surface reaction. This was achieved by weighing ADC (35 g) into a two-necked round bottom flask containing a 100 mL solution of nitrilotriacetic acid (0.1 g/L), and the temperature was gently raised to 70 °C and refluxed for 24 h. The final product was filtered, washed several times with millipore water and oven dried at 50 °C to obtain the nitrilotriacetic acid-functionalized A. digitata adsorbent (NFAD).

Characterization of NFAD adsorbent

The functional groups on the surface of the adsorbent were determined using FTIR (FTIR, Perkin Elmer, spectrum RXI 83303, MA, USA). Elemental analysis was achieved using Perkin Elmer series II CHNS/O analyzer (Perkin Elmer, 2400, MA, USA). Surface morphology was studied using SEM (SEM, JEOL JSM-6360LV, Tokyo, Japan) coupled with EDS (EDS, Thermo Noran, 6714A-ISUS-SN, WI, USA). Further structural information was obtained using X-ray diffraction (XRD-7000 X-Ray diffractometer, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with filtered Cu Kα radiation operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. The XRD pattern was recorded from 10 to 80 °C of 2θ per second with a scanning speed of 2.0000° of 2θ per minute. Zeta potential was determined using a zeta potential analyzer (DT1200, Dispersion technology, NY, USA) and thermal stability and fraction of volatile components was monitored using DTA-TG apparatus (C30574600245, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). The surface area was determined by nitrogen adsorption at 373 K using BET method in a Quantachrome Autosorb 1 instrument (10902042401, Florida, USA).

Equilibrium study

Batch adsorption equilibrium study was carried out by contacting 0.5 g of NFAD with 250 mL varying concentration (25–200 mg/L) of Pb (II) and Cu (II) solutions in 500 mL beaker at 298 K and 200 rpm for 5 h. Several agitations at 298 K and 200 rpm were repeated in order to establish the equilibrium time. Equilibrium concentration of Pb and Cu was determined by withdrawing clear samples at an interval of 1 min and analyzed using Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Varian AA240FS). High concentration range of 10–200 mg/L was used in this study because such high concentration may be found in highly polluted industrial wastewater which is the aim of this study.

Effect of NFAD dose on adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions

The effect of NFAD dose was evaluated by varying the weight of NFAD adsorbent from 0.1 to 1.0 g in 250 mL of 100 mg/L solution of adsorbate while stirring at 200 rpm in a 500 mL beaker for 5 h at 298 K. These concentrations of Pb (II) and Cu (II) were established after several equilibrium studies. Clear supernatant was withdrawn at an interval of 1 min and analyzed using Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Varian AA240FS).

Effect of pH on adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions by NFAD

Accurately weighed amount (0.5 g) of NFAD was placed in 250 mL solution of 100 mg/L solution of Pb and Cu, respectively. Each was separately adjusted over a pH of 1.70–6.20 using 0.1 M HCl and 0.1 M NaOH as required. This was stirred at 200 rpm in a 500 mL beaker for 5 h at 298 K. Clear samples were withdrawn at an interval of 1 min and analyzed using Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Varian AA240FS).

Effect of temperature on adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions by NFAD

Effect of temperature on metals uptake was evaluated by contacting 0.5 g of NFAD with 250 mL of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ion solution of different initial concentrations (25–200 mg/L) and at different temperatures ranging from 298 to 348 K. The solutions were stirred at 200 rpm in a 500 mL beaker for 5 h. Clear samples were aspirated at an interval of 1 min and analyzed using Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Varian AA240FS).

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of NFAD adsorbent

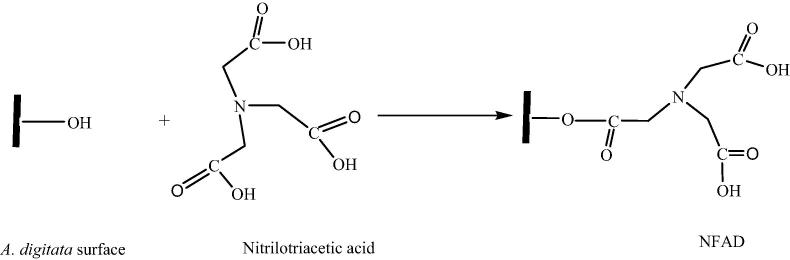

The synthesis of NFAD is presented in Scheme 1. The seed of A. digitata was extracted with n-hexane to remove non-polar compounds while hemicellulose and lignin were partially removed without total conversion to cellulose. This was carefully done to ensure that the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the biomass were free and less shielded by other possible available groups. This was also meant to remove any other compounds that may be extracted into the water system during adsorption. The FTIR results (Fig. 1a) of A. digitata seed revealed peak at 3350 cm−1 which may be attributed to the —OH functional groups while peaks at 2950 and 2830 cm−1 were considered as being peaks from the methyl (—CH3) and methylene (—CH2) functional groups. After functionalization with nitrilotriacetic acid, the intensity of the —OH group reduced with the appearance of peaks at 1722 cm−1 and 2506 cm−1 which could be attributed to the C O stretching and O—H vibrational frequency of the carboxyl functional group, respectively. Peak was also observed at 1422 cm−1 which was accounted for as being the peak of amine function group at the surface of NFAD as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of NFAD adsorbent.

Fig. 1.

(a) FTIR of Adansonia digitata seed and NFAD, (b) Zeta potential of NFAD, (c) TG and DTG of Adansonia digitata seed, (d) TG and DTG of NFAD, and (e) XRD of Adansonia digitata seed and NFAD.

The CNH analysis revealed the presence of C, H and N. The amount of carbon increased from 39.01% in the A. digitata seed to 43.77% in NFAD, and hydrogen increased from 6.27% in the seed to 6.45% in NFAD while nitrogen was only found in NFAD to be 0.57%. Zeta potential against pH is shown in Fig. 1b. The zeta potential was found to be highest in the pH range of 4–7 which was the same pH at which NFAD performed best for the removal of both Pb (II) and Cu (II). The zeta potential was found to first increase as pH values increased but on getting to high alkaline pH value, the zeta potential dropped drastically which may be due to the presence of carboxylic functional group at the surface of NFAD; since carboxyl group has a pKa which ranged from 4 to 5, the tendency to become deprotonated increases as the pH increases thus leaving the net surface charge negative.

Result of the thermogravimetric analysis is presented in Fig. 1c for the A. digitata seed while that of NFAD is shown in Fig. 1d. Thermogravimetric measurements were used to estimate the characteristic decomposition pattern, degradation, organic and inorganic content of NFAD and A. digitata seed. Weight loss at temperature below 190 °C was attributed to removal of the physisorbed water. A sharp weight loss was also noticed within the range 200–300 °C which may be due to predominant decomposition of hemicelluloses; loss of weight was also found in the range 300–350 °C which was accounted for as being decomposition of cellulose while weight loss above 350 °C was mostly due to decomposition of lignin [23]. The TGA results demonstrated that NFAD have a good degree of surface functionalization with complete degradation above 700 °C while the DTA result revealed that the loss in weight was exothermic in nature. X-ray diffraction patterns of the seed of A. digitata and that of NFAD are shown in Fig. 1e. The NFAD pattern is typical of semicrystalline material with an amorphous broad hump [24]. The more crystalline pattern of NFAD over the seed was due to the reduction and removal of amorphous non-cellulosic compounds by the alkali and also the removal of lignin by sodium chlorite in the modification process. The particle distribution was found to be monomodal while the BET surface area of NFAD was found to be very small (<1 m2/g); similar low surface area has been reported by Hanzlík et al. [25] and Nantapipat et al. [26]. This low surface area suggests that the adsorptive capacity of NFAD is most likely to be dependent on the functional group (—COOH) at its surface and the process is possibly going to be via chemisorptions.

The surface of the seed before modification (Fig 2a) seems heterogeneous which may be due to the presence of different functional groups on this surface. The surface changed after modification with nitrilotriacetic acid as seen in Fig. 2b (NFAD surface) while c and d are surfaces of NFAD after adsorption of Cu (II) and Pb (II), respectively. The EDS result of the surface content of NFAD before adsorption is shown in Fig. 2e while Fig. 2f shows the presence of Cu and Pb on the surface of NFAD after adsorption. The appearance of gold peaks in all the EDS spectra resulted from the gold used to coat the surface of NFAD during sample preparation in order to increase electrical conductivity and to improve the quality of the micrographs.

Fig. 2.

(a) Surface of Adansonia digitata seed, (b) surface of NFAD, (c) surface of NFAD covered with Cu, (d) surface of NFAD covered with Pb, (e) EDS of NFAD surface, and (f) EDS of NFAD surface covered with Cu and Pb.

Equilibrium study

The amounts of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions adsorbed by NFAD were calculated using equation:

| (1) |

where qe is the amount adsorbed in mg/g, and and are initial and final concentrations (mg/L) of adsorbates (Pb (II) and Cu (II)) in solution respectively, while V and M are volumes (L) of metal ions solution and weight (g) of NFAD used. The effect of contact time on the amounts of metal ions adsorbed is presented in Fig. 3. After several experimental trials the adsorption capacities of NFAD for Pb were determined to be 54.417 mg/g while those of Cu were found to be 9.349 mg/g. The difference in the adsorption capacities of NFAD for these potentially toxic metals may be due to the different nature of the studied metals which may be accounted for in terms of their ionic radius. The effective ionic radius of Pb (1.19 Å) differs from that of Cu (0.73 Å) at their +2 ionic state [27], [28]. Although ionic radius is not a fixed property, it varies with coordination number; nevertheless, this may have played a role in how these metals interacted with the surface of NFAD since the smaller the ionic radius the closer the electrons are to the nucleus and thus such electrons are strongly attracted to the nucleus and less available for bonding with the surface of NFAD. So, the less availability of Cu (II) electron may have reduced its interaction with NFAD surface. It was observed that the uptake of these adsorbates increased with time as well as with increase in concentration; this observation may be due to the availability of more adsorbate ions in solution with increase in concentration and time as the adsorption rate depends on the metal ions which migrate from the bulk liquid phase to the active adsorption sites on the surface of NFAD [29]. The line of graphs as shown in Fig. 3 is not smooth which may be indicative of the surface of NFAD being not completely homogeneous toward the removal of these metals, suggesting the possibility of adsorption and desorption taking place together at some point. The low BET surface area also corroborates the fact that the carboxyl functional group may have solely contributed to the adsorption process without the pores of NFAD being involved.

Fig. 3.

Adsorption capacity of NFAD toward Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions at different concentrations and time.

However, with the presence of carboxyl functional groups at the surface of NFAD and also, according to Pearson acid – base concept, NFAD may be described as a hard base with stronger affinity for borderline Lewis acids like Pb (II) than for Cu (II) which is considered to be a soft acid [30], [31]. Generally hard Lewis base will favorably bond with hard Lewis acids because hard Lewis base has Highest-Occupied Molecular Orbitals (HOMO) of low energy and hard Lewis acids have Lowest-Unoccupied Molecular Orbitals (LUMO) of high energy while on the other hand, soft acids have LUMO of lower energy which will not favor much interaction. Moreover, border line Lewis acids [Pb (II)] have intermediate properties which make them bind to hard bases to form charge-controlled (ionic) complexes [32] which may have given Pb (II) better binding capacity to the surface of NFAD than Cu (II) (which is a soft acid). This may account for the higher affinity NFAD had toward Pb2+.

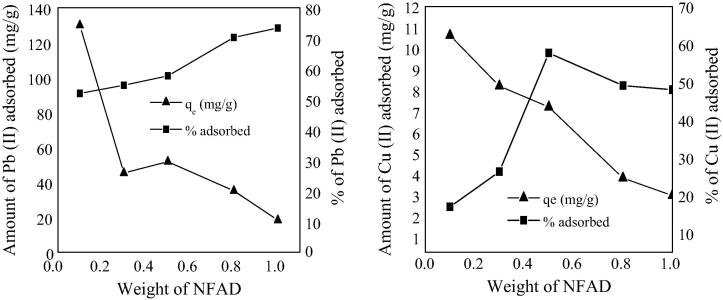

Effect of NFAD dose on adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions

On increasing the dose of NFAD from 0.1 to 1.0 g (Fig 4), its equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) decreased which may be due to decrease in gross surface area made available for adsorption by NFAD and an increase in diffusion path length, that may have risen from the aggregation of NFAD particles which was mostly significant as the weight of NFAD increased from 0.1 to 1.0 g [33]. On the one hand, the percentage of Pb (II) and Cu (II) adsorbed increased as the dose of NFAD increased which could possibly be due to increased surface negative charge and decrease in the electrostatic potential near the solid surface that favors sorbent-solute interaction [32]. The relationship between dose of NFAD used and equilibrium adsorption capacity as described by Unuabonah et al. [32] is given as follows:

| (2) |

where qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity, S is the adsorption potential of the adsorbate, Y is the maximum adsorption capacity and ms is the adsorbent dose. This equation can be used to predict the adsorption strength or capacity of NFAD per weight. The value of Y and S for Pb (II) was found to be 129.963 mg/g and −156.16, respectively while for Cu (II) they were found to be 10.631 mg/g and −6.836, respectively. The negative value of S suggests that the equilibrium capacity decreased with increase in NFAD dose.

Fig. 4.

Effect of dosage on the adsorptive capacity and % adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions on NFAD.

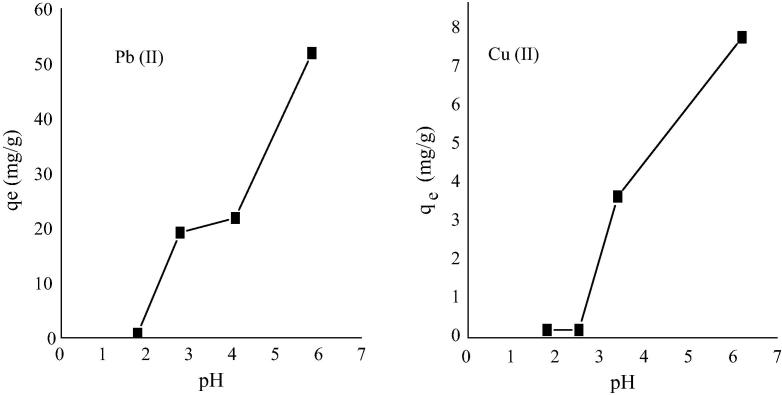

Effect of pH on adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions by NFAD

Solution pH plays a key role in the formation of electrical charges on the surface of biosorbents as these biosorbents have functional groups on their surfaces which can ionize in solution. So, when the pH value of solution is greater than the pKa of these functional groups, most functional groups on the surface of biosorbents dissociate and exchange their H+ with metal ions in solution but when the pH value is lower than their pKa value, they pick up metals by means of complexation reaction [34]. To carry out this study, precipitation of metal was avoided by maintaining a pH range of 1.70–6.20. As shown in Fig. 5, the biosorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) at reduced pH was low which might be a result of the undissociated carboxyl functional group at the surface of NFAD but as the pH gradually increased there was a rise in the amount of these metals removal from solution indicating the exchange of hydrogen ions of the carboxyl functional group with the metals and/or complexation reaction with these metals. For Pb (II), the removal was almost steady between pH 3.5 and 4 but later picked up. In the case of Cu (II) ions, there was a sharp increase in adsorption capacity after pH 4.

Fig. 5.

Effect of pH on the adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions by NFAD.

Variation in the adsorption of these metal ions with change in pH at constant weight of NFAD and metal ion concentration may be given as expressed by Sposito [35].

| (3) |

where D is a distribution ratio given as , and a and b are empirical constants. D is related to distribution coefficient (Kd) as follows:

| (4) |

A plot of ln D vs pH is termed Kurbatov plot which is important in knowing adsorption mechanism. The pH at which D = 1, where 50% of the added metal is adsorbed and 50% is in solution, is designated pH50. The pH50 for the adsorption of Pb was 2.77 while that of Cu was 3.39.

Adsorption kinetic models

Description of sorption rate is very important when designing batch adsorption technique; therefore, it is necessary to ascertain the time dependence of such technique under different process variables to understand the sorption technique. In this case, adsorption process of Pb (II) and Cu (II) on NFAD was evaluated using pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, intra-particle and liquid–film diffusion models.

Pseudo-first-order model was given as [36]:

| (5) |

On rearrangement Eq. (5) becomes

| (6) |

Nonlinear form of Eq. (6) when qt is rearranged as subject of the formula is as follows:

| (7) |

The linearized form of the kinetic rate expression for a pseudo-second-order model is given as follows:

| (8) |

where qe is the amount of Pb (II) or Cu (II) adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), qt is the amount of Pb (II) or Cu (II) (mg/g) adsorbed at time t (min) and k1 (min−1) and k2 (g/mg/min) are the rate constants of the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, respectively, for sorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions. Plot of log (qe − qt) against time t, gave a linear relationship for pseudo-first-order model from which k1 and equilibrium sorption capacity (qe), were calculated from the slope and intercept respectively. For the pseudo-second-order, the parameters ho and k2 were determined from the slope and intercept of a plot of against t. The initial sorption rate (mg/g min), ho, was obtained as follows:

| (9) |

On comparing the values obtained for the estimated model sorption capacity (qe) and the correlation coefficient (r2) of pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetics (Table 1), the sorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions on NFAD fitted better for the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and can be described using this model. The r2 values of the pseudo-second-order model were closer to unity and the qe values also correlated better with the experimental sorption values which indicates that the sorption of Pb and Cu by NFAD may be via chemisorption. The initial sorption rate of Pb (II) ions (7.042 mg/g min) was higher than that of Cu (II) ions (1.317 mg/g min) which further shows that Pb (II) ions was better adsorbed on NFAD than on Cu (II) ions.

Table 1.

Kinetic model parameters for the sorption of Cu (II) and Pb (II) on NFAD.

| Model | Parameter | NFAD |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cu | ||

| Pseudo-first-order | qe (mg/g) | 24.604 | 1.9011 |

| K1 (min−1) | 0.010 | 0.004 | |

| r2 | 0.976 | 0.965 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | qe (mg/g) | 52.632 | 7.042 |

| K2 (g/mg/min) | 2.542E−03 | 2.656E−02 | |

| r2 | 0.986 | 0.982 | |

| h (mg/g min) | 7.042 | 1.317 | |

| Elovich | qe (mg/g) | 20.40 | 3.908 |

| β (g/mg) | 0.167 | 1.689 | |

| α (mg/g/min) | 0.149 | 2.533 | |

| r2 | 0.847 | 0.852 | |

| Intra-particle diffusion | Kid (mg/g/min1/2) | 2.723 | 0.136 |

| C (mg/g) | 23.91 | 5.040 | |

| r2 | 0.935 | 0.955 | |

| Liquid film diffusion | Kfd | 2.358 | 0.012 |

| r2 | 0.940 | 0819 | |

| Experiment | qe (mg/g) | 51.883 | 7.005 |

In order to gain further insight into the mechanism of adsorption, the data were subjected to the linearized form of the Elovich equation as expressed below:

| (10) |

A straight line from the plot of qt vs ln t agrees with Elovich with a slope of (1/β) and an intercept of 1/β ln(αβ); α is the initial adsorption rate (mg/g min) while β is the extent of surface coverage and the activation energy for chemisorption (g/mg). The calculated values of qe (20.40 mg/g for Pb and 3.908 mg/g for Cu) and β (0.167 g/mg for Pb and 1.689 g/mg for Cu) are shown in Table 1 which further suggests that the sorption of these metals could have been by chemisorptions.

Intra-particle diffusion was used to estimate the sorption rate limiting step as follows [34], [36]:

| (11) |

kid is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant (mg/g/min1/2) and C (mg/g) is a constant which reflects the thickness of the boundary layer, i.e. the larger the value of C the greater the boundary layer effect. The value of C was 23.91 mg/g for Pb and 5.040 for Cu indicating that there was greater boundary effect for Pb sorption than in the case of Cu; thus the greater the contribution of the surface sorption in the rate controlling step. Straight line from the plot of qt versus t1/2 suggested that sorption process was controlled by intra-particle diffusion while the slope gave the rate constant Kid (Table 1). However, the linear plot did not pass through the origin (Fig.6) indicating that the intra-particle diffusion was not the only rate controlling step [37].

Fig. 6.

a and b) Intra-particle diffusion model for the sorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions on NFAD, c and d) Liquid-film diffusion model for the sorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions on NFAD.

Since intra-particle diffusion could not have being the only rate controlling step for the sorption of Pb and Cu onto NFAD, liquid film diffusion model was also used to investigate whether the movement of the adsorbate ions from the liquid phase up to the solid phase boundary played a role in the adsorption process according to the equation below [38]:

| (12) |

F is the fractional attainment of equilibrium given as F = qe/qt while Kfd is the adsorption rate constant. The plot of −ln (1 − F) versus t was linear as shown in Fig. 6. The Kfd and r2 (0.940 for Pb and 0.819 for Cu) values suggested that diffusion through the liquid surrounding the NFAD played a role in the kinetics of the sorption process. So, aside the intra-particle diffusion, liquid film diffusion also played significant role in the mechanism of adsorbing Pb and Cu onto the surface of NFAD. The mechanism of adsorption of adsorbate on adsorbent is known to follow series of steps; the slowest of these steps is considered to control the overall rate of the adsorption process [38]. Intra-particle and pore diffusion are often reported as the rate limiting step in batch process while film diffusion has been the case for continuous flow process [38]. The proposed mechanism for the uptake of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions can be described as shown in Scheme 2. This shows how the carboxyl functional groups may have possibly interacted with the metal ions in solution and perhaps picked them up. The carboxyl groups are capable of losing their hydrogen atoms to form anions which give them the possibility of interacting with metal cations in solution, thus bridging the metals via their oxygen atoms to form a chelate ring [39].

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of action of the —COOH functional group of NFAD.

Adsorption isotherm

The equilibrium sorption data of NFAD were fitted to three different isotherm models which are Temkin, Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption models. The values obtained for the isotherm parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cu (II) and Pb (II) sorption parameters for Temkin, Langmuir and Freundlich models.

| Isotherm | Parameter |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cu | |

| Temkin | ||

| A (L/g) | 0.0524 | 0.0024 |

| B | 26.890 | 6.049 |

| R2 | 0.979 | 0.996 |

| Langmuir | ||

| Qo (mg/g) | 54.417 | 9.349 |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.009 | 0.053 |

| r2 | 1 | 1 |

| RL | 0.018 | 0.001 |

| Freundlich | ||

| Kf | 0.500 | 0.499 |

| n | 1.000 | 0.999 |

| r2 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

In Temkin isotherm model, the energy of adsorption is a linear function of surface coverage as a result of adsorbent-adsorbate interactions which is characterized by a uniform distribution of the bonding energies up to some maximum binding energy. This can be expressed as follows [38]:

| (13) |

| (14) |

In Eq. (13), A (L/g) is the Temkin isotherm equilibrium binding constant, corresponding to the maximum binding energy, and constant B (J/mol) = RT/b, b is the Temkin constant related to the heat of adsorption. R is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol K), and T is the absolute temperature (K). A straight line from the plot of qe against ln Ce reflects Temkin isotherm from which B and A were determined from the slope and intercept of the straight line plotted. Both maximum binding energy and Temkin isotherm binding constant were found to be higher for Pb than for Cu which reflects the preference NFAD had for Pb over Cu.

The Langmuir isotherm describes the formation of a monolayer adsorbate on the surface of an adsorbent with an assumption of uniform energies of adsorption at the surface of the adsorbent. The linear representation of the Langmuir isotherm model is given as [32]:

| (15) |

where Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration of adsorbate, qe (mg/g) is the amount of metal adsorbed at equilibrium, Qo (mg/g) is the maximum monolayer coverage capacity and KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir isotherm constant. The values of Qo and KL were obtained from the slope and intercept of the Langmuir plot of 1/qe versus 1/Ce. The essential features of the Langmuir isotherm (RL) may be expressed as follows:

| (16) |

where Co is the initial concentration and KL is the constant related to the energy of adsorption (Langmuir Constant). When RL > 1 adsorption nature is considered to be unfavorable, linear if RL = 1, favorable if 0 < RL < 1 and irreversible if RL = 0. In this study the values of RL for both Pb and Cu were 0 < RL < 1 as presented in Table 2 indicating that a monolayer adsorption took place at the surface of NFAD just has the r2 values also supported this. This may be due to the homogeneous distribution of the active site on the surface of NFAD since Langmuir equation assumes that the surface is homogenous. Thus the process may be considered to be chemisorption. The higher the magnitude of Langmuir constant, KL, the higher the heat of biosorption and the stronger the bond formed. The KL values for Pb are higher than those of Cu meaning that the adsorptive ability of NFAD to hold Pb (II) ions is larger than that for Cu (II) ions.

Freundlich Isotherm model, describes the adsorption characteristics for the heterogeneous surface and multilayer sorption. The empirical expression shows the heterogeneity of adsorption sites, its exponential distribution and their energies. This is given as follows:

| (17) |

where Kf (mg/g) is the Freundlich isotherm constant which is an approximate indicator of adsorption capacity, n is the adsorption intensity, Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration of adsorbate and qe (mg/g) is the amount of metal adsorbed at equilibrium. 1/n is a function of the strength of adsorption in the adsorption process, so when n = 1 then the partition between the liquid and solid phases is independent of the concentration; If 1/n = <1 it indicates a normal adsorption but when 1/n = >1 it indicates cooperative adsorption; these parameters (Kf and n) are characteristic of the adsorbent-adsorbate system and are very important. The smaller 1/n, the greater the expected heterogeneity which reduces to a linear adsorption isotherm when 1/n = 1[40]. Our finding showed 1/n for both Pb and Cu to be 1 indicating a much more linear adsorption isotherm which may be due to the presence of carboxyl group on NFAD solely playing active role in the adsorption process.

Thermodynamics of adsorption

Experimental data from the effect of temperature on the adsorption process were analyzed to determine some thermodynamic parameters such as Gibb’s free energy change (ΔGo), enthalpy change (ΔHo) and entropy change (ΔSo) as presented in Table 3. The adsorption equilibrium constant bo was estimated from the expression [41]:

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

where Co and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of metals, R is universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) and T is the absolute temperature in K. The values of ΔHo and ΔSo were calculated from the slope and intercept of the linear plot of ln bo against reciprocal of temperature (1/T). As shown in Table 3, the value of qe for the adsorption of Pb (II) increased as temperature was increased from 298 to 333 K while qe values of Cu decreased on increasing temperature. However, in the case of Pb, the lower qe at lower temperatures may suggest the formation of weaker bonds at the surface of NFAD. ΔGo value was positive in both Pb and Cu and increased with increase in temperature. The positive nature of ΔGo shows that energy is required to promote the adsorption of both metals on NFAD with the energy required in the case of Cu being higher than that of Pb. As presented in Table 4, the values obtained for ΔSo were negative for Pb (−2.5857 J mol−1) but positive for Cu (13.7430 J mol−1); the negative value obtained for Pb (II) indicates a stable configuration of the metal ion on the surface of NFAD adsorbent [42] while the positive value for Cu (II) is an indication of some structural changes in the NFAD and Cu [43]. The enthalpy of adsorption, ΔHo was found to be higher for Cu than for Pb. The magnitude of these values suggests a fairly strong bonding between NFAD and the metals and that the adsorption of these metals on NFAD is endothermic in nature.

Table 3.

ΔG and qe obtained at various temperatures for NFAD.

| Pb | ||||

| T (K) | 298 | 313 | 323 | 333 |

| qe (mg/g) | 29.5130 | 29.8400 | 31.6000 | 35.1760 |

| ΔG (kJ mol−1 K−1) | 18.7487 | 19.6923 | 20.3215 | 20.9507 |

| Cu | ||||

| T (K) | 298 | 313 | 323 | 333 |

| qe (mg/g) | 7.2130 | 4.9125 | 4.2275 | 3.7125 |

| ΔG (kJ mol−1 K−1) | 27.5182 | 28.9034 | 29.8268 | 30.7502 |

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters obtained from plot of ln bo vs 1/T for NFAD.

| Parameters | Pb | Cu |

|---|---|---|

| ΔH (kJ mol−1) | 49.8341 | 231.3786 |

| ΔS (kJ mol−1 K−1) | −2.5857 | 13.7430 |

The adsorption capacity of NFAD was found to be higher than most natural and modified biosorbents in the literature as shown in Table 5. The isotherms obtained for the sorption of Cu (II) and Pb (II) on NFAD were in accordance with what had been previously reported to be Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms. Most authors in the literature also reported the mechanism of Cu (II) and Pb (II) to be via chemisorption except for Meena et al. [44] and Chen et al. [45] who reported physisorption and Ofomaja et al. [34] who reported both physisorption and chemisorption.

Table 5.

Comparison of the adsorption of Cu (II) and Pb (II) on NFAD with other adsorbents reported in the literature.

| Material | Adsorbate | qe (mg/g) | Adsorption isotherm | ΔGoads (kJ/mol) | ΔHoads (kJ/mol) | ΔSoads (J mol−1 K−1) | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walnut | Pb | 6.54 | Langmuir Freundlich | −1675.72 | 1696.80 | 11.33 | Chemisorption | [46] |

| Mansonia | Pb | 51.81 | Langmuir | −26.24 | 8.13 | −0.11 | Chemisorption & physisorption | [34] |

| Cu | 42.37 | BET | −18.66 | 15.02 | −0.11 | |||

| Acacia Arabica | Cu | 5.64 | Langmuir | 0.07 | 29.79 | 0.10 | Physisorption | [44] |

| Pb | 52.38 | Freundlich | 0.59 | 21.62 | 0.07 | |||

| Modified kaolinite clay | Pb | 42.92 | Langmuir | 4.35 | – | −21.73 | – | [32] |

| CuO nanostructures | Pb | 24.99 | Langmuir Freundlich | – | – | – | Chemisorption | [47] |

| Goethite | Pb | 45.28 | Langmuir & Freundlich | – | 48.92 | 188.18 | Chemisorption | [48] |

| Cu | 15.20 | 27.00 | 71.11 | |||||

| Calophyllum inophyllum | Pb | 4.86 | Langmuir | – | 7.793 | 29.20 | Chemisorption | [49] |

| Sugarcane saw dust | Pb | 25.00 | Freundlich & Langmuir | – | – | – | [50] | |

| Cu | 3.89 | |||||||

| Modified chitosan | Pb | 34.13 | Langmuir | – | – | – | Physisorption | [45] |

| Cu | 35.46 | Langmuir | ||||||

| NFAD | Pb | 54.42 | Langmuir & | 18.75 | 49.83 | −2.59 | Chemisorption | This study |

| Cu | 9.35 | Freundlish | 27.52 | 231.39 | 13.74 |

– = Not reported.

Conclusions

A potent biomass valorization approach was reported in this work using a facile and one step reaction to functionalize Adansonia digidata seeds. Nitrilotriacetic acid functionalized A. digitata (NFAD) biosorbent was used for the removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions from aqueous system and its efficiency was compared with those in the literature. The adsorption of these metals was found to be monolayer, second-order-kinetic and controlled by both intra-particle diffusion and liquid film diffusion. The findings of this study compared better than some reported biosorbents in the literature, and this also revealed NFAD as a promising adsorbent for the removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution of waste water.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by TWAS-CNPq. The authors are grateful to TWAS-CNPq for awarding Adewale Adewuyi a postdoctoral fellowship at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Islam M.S., Ahmed M.K., Raknuzzaman M., Mamun M.H., Islam M.K. Heavy metal pollution in surface water and sediment: a preliminary assessment of an urban river in a developing country. Ecol Indic. 2005;48:282–291. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simate G.S., Ndlovu S. The removal of heavy metals in a packed bed column using immobilized cassava peel waste biomass. Ind Eng Chem. 2015;21:635–643. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pant D., Singh P. Chemical modification of waste glass from cathode ray tubes (CRTs) as low cost adsorbent. J Environ Chem Eng. 2013;1:226–232. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su S., Xiao R., Mi X., Xu X., Zhang Z., Wu J. Spatial determinants of hazardous chemicals in surface water of Qiantang River, China. Ecol Indic. 2013;24:375–381. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong Q., Yue Q., Gao B., Li Q., Xu X. A novel amphoteric adsorbent derived from biomass materials: synthesis and adsorption for Cu(II)/Cr(VI) in single and binary systems. Chem Eng J. 2013;229:90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaukura N., Murimba E.C., Gwenzi W. Synthesis, characterisation and methyl orange adsorption capacity of ferric oxide–biochar nano-composites derived from pulp and paper sludge. Appl Water Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13201-016-0392-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gwenzi W., Musarurwa T., Nyamugafata P., Chaukura N., Chaparadza A., Mbera S. Adsorption of Zn2+ and Ni2+ in a binary aqueous solution by biosorbents derived from sawdust and water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) Water Sci Technol. 2014;70:1419–1427. doi: 10.2166/wst.2014.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali I. Water treatment by adsorption columns: evaluation at ground level. Separat Purif Rev. 2014;43:175–205. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali I. New generation adsorbents for water treatment. Chem Rev. 2012;112:5073–5091. doi: 10.1021/cr300133d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Y., Liu W., Zhang N., Li Y., Jiang H., Sheng G. Polyethylenimine modified biochar adsorbent for hexavalent chromium removal from the aqueous solution. Bioresour Technol. 2014;169:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilal M., Shah J.A., Ashfaq T., Gardazi S.M.H., Tahir A.A., Pervez A., et al. Waste biomass adsorbents for copper removal from industrial wastewater – a review. J Hazard Mater. 2013;263:322–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pehlivan E., Altun T., Parlayici A. Modified barley straw as a potential biosorbent for removal of copper ions from aqueous solution. Food Chem. 2012;135:2229–2234. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alhakawati M.S., Banks C.J. Removal of copper from aqueous solution by Ascophyllum nodosum immobilized in hydrophilic polyurethane foam. J Environ Manage. 2004;72:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard E., Jimoh A. Adsorption of Pb, Fe, Cu, and Zn from industrial electroplating wastewater by orange peel activated carbon. Int J Eng Appl Sci. 2013;4:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vieira M.G.A., Neto A.F.A., da Silva M.G.C., Carneiro C.N., Filho A.A.M. Adsorption of lead and copper ions from aqueous effluents on rice husk ash in a dynamic system. Braz J Chem Eng. 2014;31:519–529. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melichová Z., Hromada L. Adsorption of Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions from aqueous solutions on natural bentonite. Pol J Environ Stud. 2013;22:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rumapar K.F., Rumhayati B., Tjahjanto R.T. Adsorption of lead and copper using water hyacinth compost (Eichornia Crassipes) J Pure Appl Chem Res. 2014;3:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okafor P.C., Okon P.U., Daniel E.F., Ebenso E.E. Adsorption capacity of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) shell for lead, copper, cadmium and arsenic from aqueous solutions. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2012;7:12354–12369. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S., Li F., Wu Y., Xua R., Lib G. Preparation of novel poly(vinyl alcohol)/ SiO2 composite nanofiber membranes with mesostructure and their application for removal of Cu2+ from waste water. Chem Commun. 2010;46:1694–1696. doi: 10.1039/b925296g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Addy E.O., Eteshola E. Nutritive value of a mixture of Tigernut Tubers (Cyperus esculentus L.) and Baobab Seeds (Adansonia digitata L.) J Sci Food Agric. 1984;35:437–440. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eteshola E., Oraedu A.C.I. Fatty acid compositions of tiger nut tubers (Cyperus esculentus L.), Baobab seeds (Adansonia digitata L.), and their mixture. JAOCS. 1996;73:255–257. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adewuyi A., Oderinde R.A., Rao B.V.S.K., Prasad R.B.N., Anjaneyulu B. Blighia unijugata and Luffa cylindrica seed oils: renewable sources of energy for sustainable development in rural Africa. BioEner Res. 2012;5:713–718. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang H., Yan R., Liang D.T., Chen H., Zheng C. Pyrolysis of palm oil wastes for biofuel production. As J Energy Environ. 2006;7:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flauzino Netoa W.P., Silvério H.A., Dantasb N.O., Pasquini D. Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from agro-industrial residue – Soy hulls. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;42:480–488. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanzlík P., Jehlička J., Weishauptová Z., Šebek O. Adsorption of copper, cadmium and silver from aqueous solutions onto natural carbonaceous materials. Plant Soil Environ. 2004;50:257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nantapipat J., Luengnaruemitchai A., Wongkasemjit S. A comparison of dilute sulfuric and phosphoric acid pretreatments in biofuel production from Corncobs. Int Scholarly Scient Res Innov. 2013;7:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. 1976;A32:751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells A.F. 5th ed. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1984. Structural inorganic chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu B., Zhang Y., Shukla A., Shukla S.S., Dorris K.L. The removal of heavy metal from aqueous solutions by sawdust adsorption-removal of copper. J Hazard Mater. 2000;80:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(00)00278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson R.G. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 1997. Chemical hardness – applications from molecules to solids. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koch E.C. Acid-base interactions in energetic materials: I. The Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) principle-insights to reactivity and sensitivity of energetic materials. Prop Expl Pyrotech. 2005;30:5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unuabonah E.I., Adebowale K.O., Olu-Owolabi B.I., Yang L.Z., Kong L.X. Adsorption of Pb (II) and Cd (II) from aqueous solutions onto sodium tetraborate-modified Kaolinite clay: equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Hydrometallurgy. 2008;93:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shukla A., Zhang Y.H., Dubey P., Margrave J.L., Shukla S.S. The role of sawdust in the removal of unwanted materials from water. J Hazard Mater. 2002;95:132–152. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(02)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ofomaja A.E., Unuabonah E.I., Oladoja N.A. Competitive modeling for the biosorptive removal of copper and lead ions from aqueous solution by Mansonia wood sawdust. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:3844–3852. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sposito G. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford, England: 1984. The surface chemistry of soils. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ofomaja A.E., Unuabonah E.I. Adsorption kinetics of 4-nitrophenol onto a cellulosic material, mansonia wood sawdust and multistage batch adsorption process optimization. Carbohyd Polym. 2011;83:1192–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hameed B.H., Mahmoud D.K., Ahmad A.L. Equilibrium modeling and kinetic studies on the adsorption of basic dye by a low-cost adsorbent: coconut (Cocos nucifera) bunch waste. J Hazard Mater. 2008;158:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oladoja N.A., Aboluwoye C.O., Oladimeji Y.B. Kinetics and isotherm studies on methylene blue adsorption onto ground palm kernel coat. Turkish J Eng Environ Sci. 2008;32:303–312. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudev T., Lim C. Effect of carboxylate-binding mode on metal binding/selectivity and function in proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:85–93. doi: 10.1021/ar068181i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldberg S. Equations and models describing adsorption processes in soils. Soil Science Society of America, 677 S. Segoe road, Madison, WI 53711, USA. Chemical Processes in Soils, SSSA Book Series; 2005.

- 41.Ekpete O.A., Horsfall Jnr M., Spiff A.I. Kinetics of chlorophenol adsorption onto commercial and fluted pumpkin activated carbon in aqueous systems. Asian J Nat Appl Sci. 2012;1:106–117. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sen G.S., Bhattacharyya K.G. Adsorption of Ni(II) on clays. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2006;295:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yavuz O., Altunkaynak Y., Guzel F. Removal of copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese from aqueous solution by kaolinite. Water Res. 2003;37:948–952. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(02)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meena A.K., Kadirvelu K., Mishra G.K., Rajagopal C., Nagar P.N. Adsorptive removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution by treated sawdust (Acacia arabica) J Hazard Mater. 2008;150:604–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen A.H., Liu S.C., Chen C.Y., Chen C.Y. Comparative adsorption of Cu(II), Zn(II), and Pb(II) ions in aqueous solution on the crosslinked Chitosan with epichlorohydrin. J Hazard Mater. 2008;154:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasemin B., Zeki T. Removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution by sawdust adsorption. J Environ Sci. 2007;19:160–166. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(07)60026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farghali A.A., Bahgat M., Enaiet Allah A., Khedr M.H. Adsorption of Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions using copper oxide nanostructures. Beni – Suef University J Basic Appl Sci. 2013;2:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohapatra M., Mohapatra L., Singh P., Anand S., Mishra B.K. A comparative study on Pb(II), Cd(II), Cu(II), Co(II) adsorption from single and binary aqueous solutions on additive assisted nano-structured goethite. Int J Eng Sci Technol. 2010;2:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lawal O.S., Sannia A.R., Ajayi I.A., Rabiu O.O. Equilibrium, thermodynamic and kinetic studies for the biosorption of aqueous lead(II) ions onto the seed husk of Calophyllum inophyllum. J Hazard Mater. 2010;177:829–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Putra W.P., Kamari A., Yusoff S.N.M., Ishak C.F., Mohamed A., Hashim N., et al. Biosorption of Cu(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) Ions from aqueous solutions using selected waste materials: adsorption and characterisation studies. J Encaps Adsorp Sci. 2014;4:25–35. [Google Scholar]