Abstract

Background. Parallel upregulation of several T-cell effector functions (ie, polyfunctionality) is believed to be critical for the protection against viruses but thought to decrease in large T-cell expansions, in particular at older ages. The factors determining T-cell polyfunctionality are incompletely understood. Here we revisit the question of cytomegalovirus (CMV)–specific T-cell polyfunctionality, including a wide range of T-cell target proteins, response sizes, and participant ages.

Methods. Polychromatic flow cytometry was used to analyze the functional diversity (ie, CD107, CD154, interleukin 2, tumor necrosis factor, and interferon γ expression) of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to 19 CMV proteins in a large group of young and older United Kingdom participants. A group of oldest old people (age >85 years) was included to explore these parameters in exceptional survivors. Polyfunctionality was assessed for each protein-specific response subset, by subset and in aggregate, across all proteins by using the novel polyfunctionality index.

Results. Polyfunctionality was not reduced in healthy older people as compared to young people. However, it was significantly related to target protein specificity. For each protein, it increased with response size. In the oldest old group, overall T-cell polyfunctionality was significantly lower.

Discussion. Our results give a new perspective on T-cell polyfunctionality and raise the question of whether maintaining polyfunctionality of CMV-specific T cells at older ages is necessarily beneficial.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, T-cell polyfunctionality, CD4+ T cells, CMV target proteins

The numbers of fresh, naive cells leaving the thymus declines early in life. However, T-cell numbers are maintained at a constant level in adults [1] because memory T cells proliferate to compensate for this shortfall. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) appears to be a uniquely effective driver of this compensatory proliferation, sometimes producing very large T-cell expansions [2, 3]. It is unclear how these changes affect the functional diversity (ie, polyfunctionality) of T cells. Polyfunctionality is an important T-cell quality, which has been linked to protection in certain vaccine models [4–7]. Several studies have explored T-cell polyfunctionality at older ages, but it is not known whether this varies with respect to the CMV protein target and/or response size. Previous work on CMV-related T-cell polyfunctionality has focused on just 1 or 2 frequently recognized, reportedly dominant CMV proteins [8, 9], but it is unlikely that the polyfunctionality of 1 or 2 dominant responses sufficiently captures the overall polyfunctionality of the T-cell response (including dominant and subdominant responses) to this pathogen [10]. We therefore decided to revisit this interesting question, taking into account a wider, more representative range of CMV target proteins than previously studied. By analyzing 5 functional readouts for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to the 19 most representative CMV target proteins [11] in young and older people, we explored whether polyfunctionality is fully preserved in older people and how this is linked to target protein specificity and response size.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the United Kingdom National Research Ethics Service (09/H1102/84). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Blood Donors

As part of a larger study, CMV-specific T-cell responsiveness was examined in CMV-infected (ie, IgG-seropositive) young (19–35 years old) and older (60–85 years old) individuals in East Sussex, United Kingdom. Healthy young volunteers included university students/staff; healthy older volunteers were recruited through general practitioners affiliated to the United Kingdom National Institute of Health Research Primary Care Research Network. Exclusion criteria were known immunodeficiency (including human immunodeficiency virus infection), organ transplantation, use of immunosuppressive or immunomodulating drugs within the last year (excluding acetylsalicylic acid ≤100 mg/day), current neoplastic disease or treatment for cancer within the previous 5 years, insulin-dependent diabetes, moderate or advanced renal failure, liver disease, endocrine disorders (except corrected thyroid dysfunction), autoimmune disease, dementia/mental incapacity, alcohol/other drug abuse, acute infection or illness in the last 4 weeks, and raised body temperature (>37.5°C).

An additional 22 CMV-positive individuals with previously known T-cell responsiveness to CMV were recruited in Parma, Italy, as a comparison group of individuals of particularly advanced age (85–102 years; hereafter referred to as “oldest old”). Inclusion criteria for Italian volunteers were minimum age of 85 years and known CMV responsiveness; exclusion criteria were evidence of endocrine disorders (except thyroid dysfunction), autoimmune and neoplastic diseases, acute infections or illness in the last 2 months, renal or liver failure, and use of immunomodulatory medications (including steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, acetylsalicylic acid >100 mg/day, or immunosuppressive drugs). Individuals with cerebrovascular and/or cardiovascular disease were accepted, as the goal was to include individuals representative of such an advanced age cohort. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Cytomegalovirus-Positive Participants in the United Kingdom and Italy, by Age Group

| Parameter | Young, United Kingdom (n = 26) | Older, United Kingdom (n = 69) | Oldest Old, Italy (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Range | 19–35 | 60–85 | 85–103 |

| Mean ± SD | 23.3 ± 4.2 | 69.0 ± 7.5 | 95.9 ± 5.9 |

| Female sex | 18 (69) | 35 (51) | 16 (73) |

| Male sex | 8 (31) | 34 (49) | 6 (27) |

| White (British or Italian) | 18 (69) | 69 (100) | 22 (100) |

| Nonwhite Britisha | 8 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data are no. (%) of participants, unless otherwise indicated.

a Included 1 Syrian, 2 Indian, 1 Sri Lankan, 1 Bangladeshi, 1 Malaysian, 1 White/Asian, and 1 Black African/Asian participants.

CMV Status

CMV serological analysis (by use of the Architect CMV IgG assay, Abbot, Maidenhead, United Kingdom) was performed in the Brighton and Sussex University Hospital Trust virology laboratory.

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Isolation and Activation

PBMCs were isolated from fresh, sodium heparin-anticoagulated venous blood by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Hypaque, PLUS Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) [12]. PBMCs were resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/mL in complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, United Kingdom) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Fisher). Twenty-five micrograms per peptide of CMV peptide pools (PepMix; JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany) was dissolved in 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, United Kingdom). A total of 2 µL of peptide solution, 1.5 µL of anti-CD107a (BD), and 0.5 µL of Monensin (BD) were added to 56 µL of complete medium and placed in 4.5-mL polystyrene tubes (BD). Then 200 µL of PBMC suspension was added, and tubes were incubated at 37°C in a standard incubator in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Brefeldin A (5 µg/mL; Sigma) was added after 2 hours, and samples were incubated for additional 14 hours. Final concentrations of peptide were 1 µg/mL per peptide for each pool. Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO and used at 1 µg/mL (final concentration) as a positive stimulation control; peptide solvent (DMSO) alone served as a negative control. At the end of the incubation time, 100 µL of a 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) buffer was added to each tube and incubation continued for 10 minutes at 37°C. EDTA buffer was freshly prepared by adding Na EDTA (Sigma) to wash buffer consisting of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide (Sigma). Tubes were vortexed and then incubated for a further 10 minutes at 37°C. After spinning at 400×g for 8 minutes at 4°C, pellets were washed once more with wash buffer (same centrifuge settings) and then resuspended for staining.

CMV Peptide Pools

Peptides (15 amino acids long, with 11 overlaps between adjacent peptides) covering the amino acid sequences for CMV proteins UL28, UL32, UL36, UL48, UL55, UL82, UL83, UL86, UL94, UL99, UL103, UL122, UL123, UL151, UL153, US3, US24, US29, and US32 were prepared by solid-phase synthesis [11, 13]. All peptides were quality controlled by mass spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography. Peptide purity was >80%. One single pool was generated for each protein, except for the largest protein, UL48, for which 2 pools were generated (Pepmix; JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany). Freeze-dried pools were stored at −80°C. The 19 original CMV peptide pools were arranged in 16 stimulation pools, of which 12 pools contained just 1 protein (expected to elicit frequent responses) and 4 pools contained 2 proteins each (expected to elicit less frequent responses; Table 2).

Table 2.

Cytomegalovirus Peptide Pools Used for Stimulation

| Tube | Protein(s) | Peptides, No. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | UL55 | 224 |

| 2 | UL83 | 138 |

| 3 | UL86 | 340 |

| 4 | UL122 | 120 |

| 5 | UL123 | 143 |

| 6 | UL99 | 45 |

| 7 | UL153 | 67 |

| 8 | UL32 | 260 |

| 9 | UL28 | 92 |

| 10 | UL48Aa | 281 |

| 11 | UL48Ba | 281 |

| 12 | US3 | 44 |

| 13 | UL151 + UL82 | 219 (82 + 137) |

| 14 | UL94 + US29 | 197 (84 + 113) |

| 15 | UL103 + US32 | 103 (60 + 43) |

| 16 | US24 + UL36 | 240 (123 + 117) |

a UL48 was divided into 2 pools for stimulation (UL48A and UL48B), but results were combined.

Antibodies

We used the following fluorescence-conjugated monoclonal antibodies and staining reagents: anti-CD3-v500, anti-CD8-allophyocyanine (APC)-H7, anti-CD27-phycoerythrine (PE), interleukin 2 (IL-2)-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-Alexa 700, and CD107a-APC (all BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom); anti-CD4-peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP), anti-interferon γ (IFN-γ) PE-cyanine 7, anti-CD154 Pacific-Blue (BioLegend, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti-CD45RA-ECD (Beckman Coulter, United Kingdom), and Yellow live-dead stain (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom).

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Staining antibodies were added, and tubes were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. After a further wash, red blood cells were lysed with FACS Lysing solution (BD) and then permeabilized with BD Permeabilizing solution 2 (BD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were then stained intracellularly following the same steps as used for surface staining. Following a final wash, pellets were resuspended and fixed in PBS containing 0.5% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) prior to acquisition on an LSRII flow cytometer, using FACSdiva 6.1 software (BD).

Data Analysis and Gating Strategy

After stimulation, activated cells were enumerated by flow cytometry, using 5 simultaneous T-cell activation readouts: CD107, CD154, IL-2, TNF, and IFN-γ. Data analysis was performed with FlowJo-v9.x software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Details of the gating strategy are available in Supplementary Figure 1. Individual gates were set on activation-marker-positive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. For each subset these were combined using the Boolean gate function in FlowJo, generating 32 subsets each (31 functional subsets and 1 without any of the tested functions). Net subset frequencies were determined by background subtraction (subset by subset). Responses were considered negative if they were not identifiable by at least 1 activation marker and a visible cell cluster exceeding 1/10 000 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (0.01%).

Polyfunctionality

SPICE software was used to visualize and analyze nonoverlapping functional subsets [14]. The polyfunctionality index (PI) algorithm was obtained from FunkyCells ToolBox, version 0.1.0 beta (available at: http://www.FunkyCells.com) [15]. To calculate the PI, each subset defined by a given number of displayed functions has a weight assigned, which is then multiplied with the subset frequency. The PI is the sum of these products (, where Fi is the frequency of cells performing i simultaneous functions, q is the polyfunctionality parameter determining the weight of the subsets, and n is the number of possible functions). The polyfunctionality parameter q was set to 1 as previously described [15]. Samples containing <0.1% activated events were not included in correlations of PI and other parameters.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS v22 software (IBM, London, United Kingdom) was used for statistical analysis. Nonparametric (eg, Mann–Whitney) tests were used to compare groups unless normality of the data distribution was assumed (based on Q/Q plots and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Differences between >2 groups (independent samples) were tested with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Differences with respect to several parameters (related samples) were tested with Friedman analysis of variance. Where appropriate, T-cell frequencies were log transformed to normalize distribution or improve visual presentation. P values of <.05 were considered significant for single end points. Where there were multiple end points, Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the significance level from P ≤ .05 to P ≤ .05/n, where n is the number of end points.

RESULTS

The Functional T-Cell Subset Distribution Is Very Similar in Young and Older United Kingdom Participants

CMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed in a healthy United Kingdom cohort (2 age groups) and a cohort of oldest old Italians. The main interest in the latter group was to contrast findings in the older group (within the normal life expectancy) against exceptional survivors. They were not considered examples of normal aging.

After stimulating PBMCs with 19 representative CMV target proteins, the 5 simultaneously measured T-cell activation readouts (CD107, CD154, IL-2, TNF, and IFN-γ) gave rise to 32 functional (Boolean) subsets when positive/negative populations were gated for each marker (n = 25), but the subset negative for all markers was discounted from the analysis, leaving 31; these were visualized using SPICE software [14]. However, none of the functional CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell subsets was significantly different between the young and older United Kingdom participants, when analyzing UL83-specific responses (Supplementary Figure 2); this was also true for UL55-specific CD4+ T cells and UL123-specific CD8+ T cells (data not shown). For this type of analysis, the significance threshold was set at a P value of ≤ .0016 (Bonferroni multiple end point correction; 31 end points).

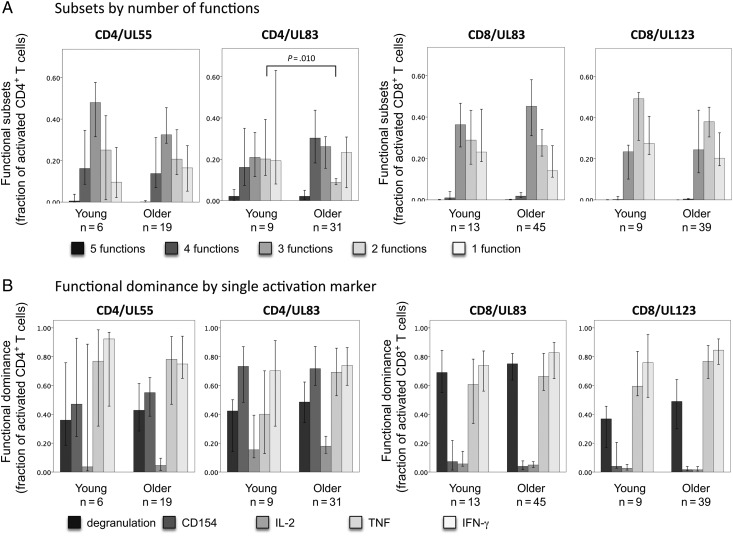

To reduce the complexity of the information, we determined the proportions of T-cell subsets with specific numbers of parallel functions (1 to 5; Figure 1A). These were very similar in young and older people, except for a slightly (but significantly) higher proportion of UL83-specific CD4+ T cells with 2 functions observed in the older people. We also studied the total percentage of cells expressing each activation marker, to explore functional marker dominance (note that such subsets overlap). However, no significant differences were visible (Figure). Nevertheless, the data shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 2 suggest that many smaller subset differences might exist and that the lack of statistical significance could be due to the small group sizes, particularly among the young. The number of participants with a UL55-specific CD4+ T-cell response and UL123-specific CD8+ T-cell response were only 6 of 26 and 9 or 26, respectively, among the young participants, but these were the second and third most frequently recognized proteins in the study. This meant it was highly unlikely that we would be able to recruit sufficient numbers of responders for each protein to complete a representative comparison between the age groups protein by protein. We therefore decided to base the comparison of polyfunctionality on all present T-cell responses in the 2 age groups, irrespective of the recognized target protein. In addition, we decided to use an algorithm that would assign an aggregate measure of polyfunctionality to each response, because interpreting group differences with respect to multiple percentages of subsets with slightly different functional characteristics appeared to be too complex. We therefore applied the recently introduced polyfunctionality index (PI) to our data. The PI is a compound measure, which elegantly reduces the complexity inherent in multiple subset comparisons to a single index number [15, 16].

Figure 1.

The functional T-cell response composition in young and older people appears to be very similar. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from cytomegalovirus (CMV)–positive donors were stimulated overnight with 19 CMV protein–derived overlapping peptide-pools. Activated T cells and their functional composition were analyzed by flow cytometry, including the activation markers, degranulation (CD107), CD154, interleukin 2 (IL-2), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interferon γ (IFN-γ). Responses from the United Kingdom cohort are shown for the 2 most frequently targeted proteins for each T-cell subset. A, Nonoverlapping subsets exhibiting 5, 4, 3, or 2 parallel functions or just 1 single function are shown as a proportion of the specifically activated T cells (in order of decreasing polyfunctionality). A significant difference between the age groups is observed for UL-83–specific CD4+ T cells with 2 functions, but, on the whole, subset distributions appear to be very similar. B, The functional dominance of each activation marker in a given response is assessed by the proportion of activated cells expressing it. Some variability between proteins was revealed, but there was no significant differences between the age groups. There were 5 end points evaluated, with the significance threshold set at a P value of ≤ .01. P values were determined by the Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni correction for multiple end points.

The PI Is Very Similar in the Young and Older United Kingdom Groups but Lower in the Oldest Old Survivors

We first determined the PI for every single response and then the average PI for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in each individual. This allowed us to include all responses to all 19 proteins in our comparison. Surprisingly, the average PI appeared to be slightly higher in the older participants, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

The polyfunctionality index of cytomegalovirus (CMV)–specific T-cell responses varies between protein targets and is reduced in the oldest old group. The polyfunctionality index (PI) captures functional subset distributions by weighting the number of functions, as well as subset size [15, 16]. For the present study, a linear relationship between the number of functions and the relative weight of a subset was selected (eg, subsets with 2 functions were assigned twice the weight of subsets with 1 function and subsets with 3 functions were assigned 3 times the weight of subsets with 1 function). A, In each individual, the PI was calculated for all positive responses and averaged. Dot plots show the distribution of the average PI in young and older United Kingdom individuals for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. No significant differences between the groups were observed. B, The comparison of the average PI between the older and the oldest old groups reveals significantly reduced polyfunctionality in the latter. C, The PI of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses is shown by target protein for the 5 most frequently recognized proteins in each T-cell compartment (each protein was recognized by ≥10 donors; only young and older United Kingdom donors were included in this analysis). Differences apparent for CD4+ T cells were not statistically significant (by the Kruskal–Wallis Test), but the data suggest that responses to UL83 were the most polyfunctional (upper left). However, significant differences are revealed for CD8+ T cells (upper right). Responses to UL83 showed the highest and responses to UL32 the lowest polyfunctionality. Lower panels show T-cell response size for each target protein (CD4+ T cells on the left and CD8+ T cells on the right), and box plots show medians, interquartile ranges, and outliers (o). D, Interestingly, with respect to each analyzed protein, the PI significantly correlated with response size in a linear fashion. Correlations were moderate to strong. The strongest correlation was found for CD4+ T-cell responses to UL83 (only United Kingdom donors were included in this analysis). Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

However, the oldest old individuals, who were considered examples of exceptionally successful aging, showed a significantly lower PI in their CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses than the older participants (Figure 2B). When comparing the UL83-specific T-cell response between the older and oldest old participants in more detail, using SPICE [14], larger percentages of functionally focused subsets (1 or 2 functions) present in the latter were consistent with this observation (Supplementary Figure S3). In particular, they had higher frequencies of UL83-specific CD4+ T cells upregulating CD154 and IFN-γ or degranulation alone. Among UL83-specific CD8+ T cells, the subsets displaying IFN-γ alone or IFN-γ and degranulation were significantly increased, compared with the older group. The subset displaying degranulation alone also seemed markedly increased, but this difference did not achieve statistical significance. Concerning UL55-specific CD4+ T-cell responses, the oldest old had higher frequencies of the subset displaying only degranulation (mirroring the UL-83–specific response), but there were no differences in the other subsets (data not shown). For UL123-specific CD8+ T cells, by contrast, no significant differences were found (data not shown).

Polyfunctionality Varies Between Responses Targeting Different Proteins but Is Related to Response Size

We also applied the PI to the comparison of protein-specific responses in the United Kingdom cohort (young and older participants together). For this purpose, we selected the 5 most frequently recognized CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell target proteins. Whereas differences for CD4+ T cells were apparent but not statistically significant (Figure 2C, left), significant differences were observed for CD8+ T cells (Figure 2C, right). To elicit how individual functional subsets reflected these differences for the most frequently recognized proteins, we used SPICE [14]. Visualization of all individual subsets suggested that UL55-specific CD4+ T cells included significantly larger subsets displaying IFN-γ and TNF, or IFN-γ, TNF, and degranulation (CD107) than UL83-specific CD4+ T cells. Meanwhile, UL123-specific CD8+ T cells included significantly larger subsets displaying IFN-γ and TNF in combination or alone than UL83-specific CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Figure S4). An increase of subsets focused on single effector markers is consistent with a loss of polyfunctionality.

Interestingly, there seemed to be different levels of polyfunctionality for responses targeting different proteins. Of note, these levels per se did not seem to depend on whether average responses to a protein were large or small. For example, UL123 induced significantly larger CD8+ T-cell responses than UL83 (Figure 2C, bottom right), but the responses to UL83 were significantly more polyfunctional (Figure 2C, top right). A similar trend was seen for CD4+ T-cell responses to UL55 (bigger) and UL83 (more polyfunctional), but differences were not significant. However, with respect to individual proteins, there was a significant association between PI and response size. This was observed for CD4+ T-cell responses to UL83 and UL55 (Figure 2D, top), as well as for CD8+ T-cell responses to UL83 and UL123 (Figure 2D, bottom). Similar but statistically nonsignificant associations between response size and PI were observed for 1 additional CD8+ T-cell and 2 additional CD4+ T-cell among the top 5 recognized proteins in each T-cell compartment (the numbers of cases were lower than for the 3 dominant proteins mentioned above).

Finally, the differences in PI between UL83- and UL55-specific CD4+ T cells, as well as UL83- and UL123-specific CD8+ T cells (P = .018 and P = .066, respectively; data not shown) were preserved in the oldest old group, albeit not statistically significantly so for CD8+ T cells. An association between response size and PI was visible in the oldest old for the same proteins as in the United Kingdom cohort but only as a nonsignificant trend (due to a lack of sufficient numbers of observations; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study provides a comprehensive analysis of the polyfunctionality of CMV-specific T cells at different ages. It covers CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to 19 different CMV target proteins, examines healthy participants in 2 different age groups, and also includes a cohort of successfully aged, oldest old individuals for comparison. We analyzed 5 simultaneous functional readouts and applied the recently introduced PI in addition to conventional subset-by-subset analysis. Use of the PI enabled us to analyze (aggregate) polyfunctionality in individuals and groups of individuals, responses to different proteins, as well as correlations between polyfunctionality and response size.

Our results agree with published reports indicating that age per se is not linked to reduced polyfunctionality of CD8+ T-cell responses to a range of different organisms [17] or altered CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to superantigens [18]. For statistical robustness, when comparing the PI between T-cell responses of different protein specificities, we focused on the most frequently recognized ones (U83, UL123, and UL55). But when comparing the PI of CMV-specific T-cell responses between age groups, all responses to all proteins were accounted for. Since for each individual, the average PI across their specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses was computed prior to comparing these averages between the age groups, our approach provided unprecedented coverage of CMV target proteins for the analysis of polyfunctionality. It convincingly demonstrates that aging within the expected life-span in the United Kingdom (and many other countries in the world) has no obvious detrimental effect on the functional diversity of CMV-specific T cells.

With respect to what determines T-cell polyfunctionality, it is interesting that responses to different target proteins had different PIs. This might be explained by the presentation of different CMV proteins by antigen-presenting cells in different contexts [19] and/or the efficiency of antigen presentation, including T-cell receptor antigen sensitivity and the amount of antigen available [20]. It is conceivable that the same protein might elicit responses of different polyfunctionality (and magnitude) in cohorts of different genetic background (ie, certain HLA-types might contribute to the presentation of peptides that are recognized with higher T-cell receptor affinity and avidity than others) [21]. These aspects clearly warrant further study.

In addition, a striking and significant association between the PI and CD4+ and/or CD8+ T-cell response size was observed for responses to UL83, UL123, and UL55 in the young and older donors. It remains unclear whether this holds generally true for subdominant proteins. In the oldest old we saw the same trend that polyfunctionality increased with response size, but there were not enough cases for correlations to reach statistical significance.

The present study significantly extends recent work in a large group of (exclusively) older people with respect to UL83-specific T-cell responses [8]. That study showed a correlation between the increase of certain polyfunctional subsets (eg, exhibiting TNF, IFN-γ, and perforin expression, as well as degranulation) and the size of the UL83-specific T-cell response. However, unlike in the present study, T-cell polyfunctionality was not assessed by an aggregate measure such as the PI, and other proteins were not included. Also, a comparison between older and oldest old individuals was not made.

Perhaps unexpectedly, results in the oldest old group demonstrated decreased polyfunctionality, with an overall reduced PI of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses. In agreement with this, our detailed subset analysis indicated that several subsets with just 1 or 2 of the measured functions were increased (eg, CD8+ T cells displaying IFN-γ alone or IFN-γ and degranulation). Studies conducted over a decade ago suggested that, in very old people, the expansion of UL83-specific T cells (recognizing specific epitopes in a narrow HLA context) was linked to functional exhaustion [22, 23]. The individuals examined in that work were similar in age to our oldest old group, and the decrease in polyfunctionality we have measured in this group might be a correlate of the functional exhaustion reported in these earlier studies, which used fewer activation markers.

In any case, it seems to go against the notion that higher polyfunctionality is associated with better protection if it is reduced in oldest old persons [15]. Protection from CMV disease (probably the most important role of CMV-specific T cells) might well be provided by a very small number of CMV-specific cells [10], but decreased polyfunctionality of large responses in very old people might reduce CMV-associated immune pathology. Such may include, for example, vascular pathology contributing to cardiovascular events and stroke, which are major causes of death in older people [12, 24–27]. It is important to remember in this context that cells with greater polyfunctionality also produce larger and potentially more harmful quantities of effector cytokines [9]. A link between CMV-specific T-cell polyfunctionality and increased immune pathology would undermine the idea that T-cell polyfunctionality at older ages is necessarily a good thing. It might be of advantage for long-term survival, by contrast, if the level of pathogen control is balanced against the risk of collateral tissue damage. Maybe this is achieved to an extent by reduced polyfunctionality of CMV-specific T-cell responses in very old people. This is an important question to be answered, in light of the growing interest in the possible role of CMV in a range of age-associated pathologies [28–30].

In conclusion, our study has revealed new aspects of CMV-specific T-cell polyfunctionality, in particular the previously unknown effects of target protein specificity and response size. While we now have a better understanding of this complex issue, the discovery that T-cell polyfunctionality in the oldest old long-term survivors is actually reduced has raised the question of whether increased T-cell polyfunctionality in older people could potentially limit survival.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the National Institutes of Health Research for kindly assisting with participant recruitment through the Primary Care Research Network.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Dunhill Medical Trust, United Kingdom (grant R107/0209).

Potential conflicts of interest. M. L. is inventor of the PI (patent no. WO2013127904) and proprietary owner of the Funky Cells ToolBox software. F. K. is a named owner/inventor on a patent describing protein-spanning peptide pools for T-cell stimulation (EP1257290 B1). Reagents covered by this patent were used in this study. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Gruver AL, Hudson LL, Sempowski GD. Immunosenescence of ageing. J Pathol 2007; 211:144–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawelec G, Akbar A, Caruso C, Effros R, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Wikby A. Is immunosenescence infectious? Trends Immunol 2004; 25:406–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Walter S et al. An age-related increase in the number of CD8+ T cells carrying receptors for an immunodominant Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) epitope is counteracted by a decreased frequency of their antigen-specific responsiveness. Mech Ageing Dev 2003; 124:477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darrah PA, Patel DT, De Luca PM et al. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat Med 2007; 13:843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8:247–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betts MR, Nason MC, West SM et al. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 2006; 107:4781–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Precopio ML, Betts MR, Parrino J et al. Immunization with vaccinia virus induces polyfunctional and phenotypically distinctive CD8(+) T cell responses. J Exp Med 2007; 204:1405–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu YL, Lin CH, Sung BY et al. Cytotoxic polyfunctionality maturation of cytomegalovirus-pp65-specific CD4 + and CD8 + T-cell responses in older adults positively correlates with response size. Sci Rep 2016; 6:19227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachmann R, Bajwa M, Vita S et al. Polyfunctional T cells accumulate in large human cytomegalovirus-specific T cell responses. J Virol 2012; 86:1001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sylwester A, Nambiar KZ, Caserta S, Klenerman P, Picker LJ, Kern F. A new perspective of the structural complexity of HCMV-specific T-cell responses. Mech Ageing Dev 2016; 158:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med 2005; 202:673–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terrazzini N, Bajwa M, Vita S et al. A novel cytomegalovirus-induced regulatory-type T-cell subset increases in size during older life and links virus-specific immunity to vascular pathology. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kern F, Faulhaber N, Frommel C et al. Analysis of CD8 T cell reactivity to cytomegalovirus using protein-spanning pools of overlapping pentadecapeptides. Eur J Immunol 2000; 30:1676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roederer M, Nozzi JL, Nason MC. SPICE: exploration and analysis of post-cytometric complex multivariate datasets. Cytometry A 2011; 79:167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd A, Almeida JR, Darrah PA et al. Pathogen-Specific T Cell Polyfunctionality Is a Correlate of T Cell Efficacy and Immune Protection. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0128714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen M, Sauce D, Arnaud L, Fastenackels S, Appay V, Gorochov G. Evaluating cellular polyfunctionality with a novel polyfunctionality index. PLoS One 2012; 7:e42403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lelic A, Verschoor CP, Ventresca M et al. The polyfunctionality of human memory CD8+ T cells elicited by acute and chronic virus infections is not influenced by age. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1003076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Epps P, Banks R, Aung H, Betts MR, Canaday DH. Age-related differences in polyfunctional T cell responses. Immun Ageing 2014; 11:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu YL, Shan L, Huang H et al. Sprouty-2 regulates HIV-specific T cell polyfunctionality. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almeida JR, Sauce D, Price DA et al. Antigen sensitivity is a major determinant of CD8+ T-cell polyfunctionality and HIV-suppressive activity. Blood 2009; 113:6351–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirchner A, Hoffmeister B, Cherepnev GG et al. Dissection of the CMV specific T-cell response is required for optimized cardiac transplant monitoring. J Med Virol 2008; 80:1604–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Zheng W, Wikby A, Remarque EJ, Pawelec G. Dysfunctional CMV-specific CD8(+) T cells accumulate in the elderly. Exp Gerontol 2004; 39:607–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Wikby A et al. Large numbers of dysfunctional CD8+ T lymphocytes bearing receptors for a single dominant CMV epitope in the very old. J Clin Immunol 2003; 23:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieto FJ, Adam E, Sorlie P et al. Cohort study of cytomegalovirus infection as a risk factor for carotid intimal-medial thickening, a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. Circulation 1996; 94:922–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savva GM, Pachnio A, Kaul B et al. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with increased mortality in the older population. Aging Cell 2013; 12:381–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spyridopoulos I, Martin-Ruiz C, Hilkens C et al. CMV seropositivity and T-cell senescence predict increased cardiovascular mortality in octogenarians: results from the Newcastle 85+ study. Aging Cell 2016; 15:389–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Berg PJ, Yong SL, Remmerswaal EB, van Lier RA, ten Berge IJ. Cytomegalovirus-induced effector T cells cause endothelial cell damage. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012; 19:772–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solana R, Tarazona R, Aiello AE et al. CMV and Immunosenescence: from basics to clinics. Immun Ageing 2012; 9:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawelec G, McElhaney JE, Aiello AE, Derhovanessian E. The impact of CMV infection on survival in older humans. Curr Opin Immunol 2012; 24:507–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiello AE, Simanek AM. Cytomegalovirus and immunological aging: the real driver of HIV and heart disease? J Infect Dis 2012; 205:1772–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.