Abstract

The combination of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and high malaria exposure are risk factors for endemic Burkitt lymphoma, and evidence suggests that infants in regions of high malaria exposure have earlier EBV infection and increased EBV reactivation. In this study we analyzed the longitudinal antibody response to EBV in Kenyan infants with different levels of malaria exposure. We found that high malaria exposure was associated with a faster decline of maternally derived immunoglobulin G antibody to both the EBV viral capsid antigen and EBV nuclear antigen, followed by a more rapid rise in antibody response to EBV antigens in children from the high-malaria-transmission region. We also observed the long-term persistence of anti–viral capsid antigen immunoglobulin M responses in children from the high-malaria region. More rapid decay of maternal antibodies was a major predictor of EBV infection outcome, because decay predicted time to EBV DNA detection, independent of high or low malaria exposure.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, P. falciparum malaria, Burkitt Lymphoma, antibody, immunity

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a gammaherpesvirus causing infectious mononucleosis and also associated with a variety of cancers in humans [1]. In Africa, EBV is associated with endemic Burkitt lymphoma in the presence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection [2]. Previous studies in Africa have shown that most children seroconvert to EBV between 6 and 18 months of age [3–5] and that living in an area of high malaria transmission is associated with higher EBV load [4] and earlier time of the first EBV infection [5]. Moreover, the presence of P. falciparum infection is correlated with increased EBV load over time and with more frequent detectable EBV in children [5, 6] and pregnant women [7]. High levels of antibody against the EBV viral capsid antigen (VCA) are associated with a higher risk of Burkitt lymphoma in both Ugandan [8, 9] and Kenyan [10] children. High malaria exposure was also associated with impaired transfer of maternal VCA and EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1)–specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G from mother to infant [11], and later in life, higher level of EBV-specific IgG antibodies [12].

The measurement of antibodies specific for EBV VCA and EBNA1 have been used in numerous seroepidemiology studies to assess primary and persistent EBV infections (reviewed in [13]). Typically, anti-VCA IgG appears early after infection, with a delay to detection of anti-EBNA1 IgG. Both are then found at relatively stable levels throughout the life of the host. Anti-EBV early antigen diffuse complex (EAd) IgG has been used as a serological marker for evidence of viral reactivation, because its levels are generally much lower than levels of anti-VCA IgG, they decrease after primary infection (in contrast to VCA IgG), and are elevated during viral reactivation. The EBV Z-transactivation antigen (Zta) is an EBV immediate early protein. It has not been used in clinical settings to detect EBV reactivation to our knowledge, but we have found that the serology of Zta is similar to that of EAd-IgG and that Zta serology can also be used as a marker of viral reactivation [12].

In this study, we used a modeling approach to investigate how malaria exposure might affect the serological profiles of EBV-infected children, and EBV infection kinetics. This study demonstrated rapid decay of maternal antibodies in the region of high malaria exposure, followed by early EBV DNA detection and higher expansion rate of EBV-specific antibodies. This expansion of EBV antibodies can be observed from 1–2 months of age, suggesting very early EBV exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Detailed methods of the cohort and analysis of viral loads from birth to 24 months have been described elsewhere [5]. Briefly, 2 cohorts of infants enrolled within 1 month of birth were monitored in Kisumu (77 children; high-malaria-transmission region) and Nandi (86 children; low-malaria-transmission region) in Kenya. The first data collection was performed when the children were about 1 month of age (range, 1–4 months), and then roughly every month until 24 months of age. Luminex bead assays were used to capture 4 different types of EBV-specific IgG to VCA, EBNA1, z-transactivation antigen (Zta), and EAd [12]. Plasma was diluted either 1:100 or 1:6400. We expressed the results as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) level of ≥75 beads. Detection of anti-VCA IgM is used clinically to evaluate whether primary EBV infection has occurred [13]. We performed the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays [14] to detect anti-VCA IgM, and we had limited sample volume to perform more extensive serological analysis. For all serological assays, pooled serum from EBV negative donors was used as negative controls. The EBV seronegative plasma was used to create baseline values for the MFI, these values were then averaged and the mean (±3 standard deviations) was subtracted from the MFI or optical density. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to detect the presence of EBV DNA in the blood, with a limit of detection of 2 copies/µg of DNA [4, 15].

Modeling the Kinetics of EBV-Specific Antibodies

Throughout this study, we modeled the kinetics of EBV-specific IgG antibodies as having potentially 2 phases. The first phase was a decline in antibody present at birth (representing the presence and loss of maternal antibodies), and the second was the subsequent increase in EBV-specific antibodies (representing the production of endogenous EBV-specific antibodies). Note that in some cases, we did not observe an initial loss of maternal antibodies. Maternal antibodies (M [t]) transferred in utero will decay at a rate δ (exponentially), while, at the same time, endogenous EBV-specific antibodies (E[t]) reflective of infection will be formed (expanding at rate g) and will later reach a constant level K. This can be written as follows:

| (1) |

where MFI (t) represents MFI level at time t; A, initial maternal EBV-specific antibody at birth; δ, decay of maternal antibody; g, intrinsic expansion rate of EBV antibody level; and K, stable level of EBV-specific antibodies. Note that in the cases of Zta- and EAd-specific IgG, we did not observe an initial presence or loss of maternal antibodies (ie, A = 0).

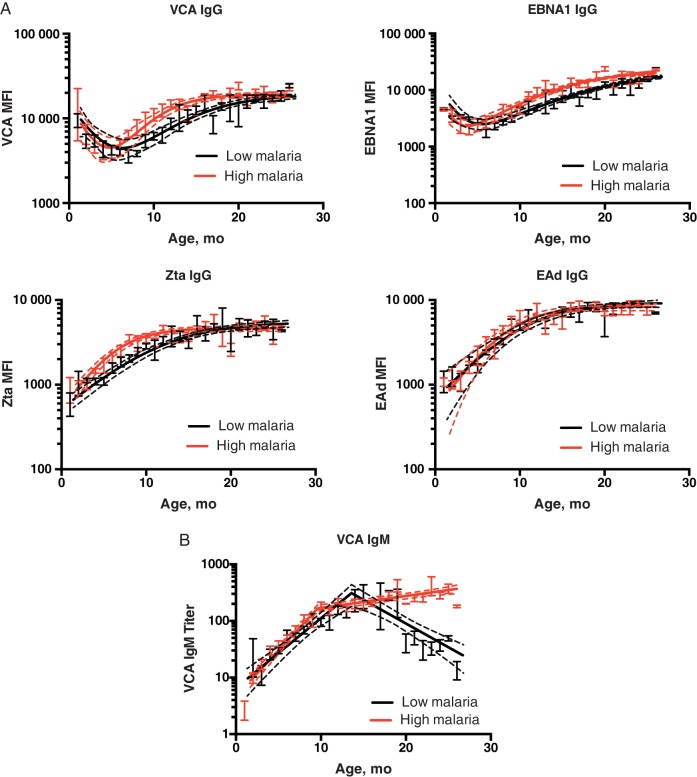

For the kinetics of VCA-specific IgM, we used a piecewise log-linear model on the level of VCA IgM titer against age. The level of VCA IgM increases exponentially until a certain time (Tlast), after which it decreases exponentially. This was chosen based on the overall trend in the dynamics of VCA IgM. Maternal IgM does not cross the placenta, and detection of VCA-specific IgM in the infants is an indicator of primary infection. Consistent with the inability of IgM to cross the placenta, we did not observe the initial presence or loss of maternal antibodies (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Serological profiles in children over time. Kinetics of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies to 4 EBV antigens: viral capsid antigen (VCA), EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1), Z-transactivation antigen (Zta), and early antigen diffuse complex (EAd). Each graph shows the model prediction (solid line) with the 95% confidence band of the model fit (dashed lines); error bars represent standard error of the mean in the data. A, Initial drop during the first few months is assumed to reflect the presence and loss of maternal antibodies (particularly antibodies to VCA and EBNA1). The later increase in antibody levels is assumed to indicate the production of endogenous EBV-specific antibodies. A complete time course of the data for individual subjects (with the model fitting) can be seen in Supplementary Figure 1. MFI, median fluorescence intensity. B, Different kinetics of VCA-specific IgM in the low- and high-malaria regions with age. In the low-malaria region, we see a later drop in the level of VCA IgM; in the high-malaria region, the level of VCA IgM is maintained.

Fitting Procedures and Statistical Analysis

We used a nonlinear mixed-effect model with fixed treatment effect to capture the difference in antibody expansion and decay parameters between the 2 regions. Significance was determined based on the value of this covariate, which can be calculated using the Wald test from the standard errors calculated in package nlme in R software (version 3.1.2). The models were fitted with the nonlinear mixed-effect model R function nlme in library nlme (version 3.1-113). The fit was weighted using varPower, and we assumed a diagonal variance-covariance matrix for the random effect, using the pdDiag option in R. To find the 95% confidence interval (CI), we used the R function intervals in library nlme.

We used Cox proportional hazard regression to determine if there was an association between the predicted parameters in the IgG responses and the time to be DNA positive. The analysis was done using the coxph function in R software from the library survival (version 2.38-1).

RESULTS

General Description

Examples of antibody levels of various EBV-specific antibodies are shown in Figure 1 (individual data in Supplementary Figure 1). For VCA-and EBNA1-specific IgG antibodies, we observed an initial high level of antibodies, which dropped during about the first 6 months of life (assumed to reflect the initial presence and loss of the maternally transmitted antibodies). After this, we observed an increase in VCA- and EBNA1-specifc IgG, assumed to be from endogenous production by infants. Anti-Zta and anti-EAd antibodies are typically used as indicators of EBV reactivation and are transiently detected. In a separate study we have shown that maternal antibodies to Zta and EAd are not efficiently transferred to infants as assessed in cord blood [11]. Consistent with this, we did not observe the initial presence or subsequent loss of maternal antibody to these antigens.

Faster Loss of Maternal IgG Antibody to VCA and EBNA1 for Children in High-Malaria Region

We first analyzed the kinetics of VCA- and EBNA1-specific IgG over time from 1 to 24 months of age, fitting a model with loss of maternal antibodies, and increase in endogenously produced antibodies (Eq 1) [3, 16]. We found that the estimated initial amount of VCA-specific IgG at birth was similar between the 2 cohorts (P = .77), consistent with the fact that the levels at enrollment 1 month later were also not significantly different (P = .84). However, the subsequent decay rate of maternal antibody to VCA was significantly faster in the high-malaria region (P < .001), with a rate of 0.23 month−1 (high-malaria region) and 0.15 month−1 (low-malaria region). The kinetics of maternal EBNA1-specific IgG showed the same trends. We found no difference in the measured level of EBNA1 IgG at first sampling (P = .75) or the level estimated to have been present at birth (P = .23). However, we found that similar to the decay of anti-VCA antibody, those living in a high-malaria region had faster decay of EBNA1 IgG than that in the low-malaria region (rates, 0.97 and 0.24 month−1, respectively; P < .001).

Faster Rate of Increase of VCA and EBNA1 IgG for Children in High-Malaria Region

Using the same model (Eq 1), we found that the rate of increase of VCA-specific IgG was higher for children in the high-malaria than for those in the low-malaria region (0.93 month−1 vs 0.76 month−1; P = .046). However, the plateau level of VCA-specific IgG achieved at a later age did not differ significantly between the 2 cohorts (P = .52). This similar plateau level could arise owing to the limitations of the assay, in which maximal binding of antibodies is reached. However, when we repeated the same analysis using data obtained when plasma was diluted 1:6400, we still observed similar levels of saturation in the 2 groups (P = .55).

The same trend can also observed in the kinetics of EBNA1-specific IgG, with faster expansion in EBNA1-specific in the high-malaria region (0.55 month−1) than in the low-malaria region (0.32 month−1; P = .06). The stable levels reached by EBNA1-specific IgG did not differ significantly between those 2 cohorts (P = .48). For a complete summary, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Dynamics of VCA- and EBNA1-Specific IgGa

| Parameter | Value (95% CI) |

P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Malaria Region | High-Malaria Region | ||

| VCA-specific IgG | |||

| Initial maternal antibody, MFI | 11 560 (9113–14 007) | 12 086 (6037–18 136) | .77 |

| Decay rate, mo−1 | 0.15 (.13–.17) | 0.23 (.18–.27) | <.001 |

| Initial EBV antibody, MFI | 14.9 (2–27.75) | 68.5 (6.4–130.6) | .03 |

| Expansion rate, mo−1 | 0.76 (.65–.87) | 0.93 (.65–1.22) | .046 |

| Threshold, MFI | 21 722 (20 141–23 303) | 19 932 (16 232–23 614) | .52 |

| EBNA1-specific IgG | |||

| Initial maternal antibody, MFI | 20 262 (18 578–28 650) | 22 262 (19 080–34 493) | .75 |

| Decay rate, mo−1 | 0.24 (.16–.32) | 0.97 (.78–1.15) | <.001 |

| Initial EBV antibody, MFI | 15.3 (1.1–29.6) | 298.8 (190–407.6) | <.001 |

| Expansion rate, mo−1 | 0.32 (.27–.38) | 0.55 (.27–.51) | .06 |

| Threshold, MFI | 24 749 (23 507–25 991) | 24 288 (21 541–26 915) | .48 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EBNA1, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; VCA, viral capsid antigen.

a Data from 77 children in Kisumu (high-malaria region) and 86 in Nandi (low-malaria region). We fitted a model of exponential decay and logistic growth (see Eq 1). Values here are the population parameter estimation of a mixed-effect model; 95% CIs were obtained using the R function intervals in library nlme.

b Significance of differences between high- and low-malaria region, determined using the Wald test from the nlme package in R.

Steady Increase in Levels of Antibodies to Zta and EAd From a Very Early age

In the majority of study participants, we could not see evidence of maternal antibodies to Zta and EAd IgG (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1), as the level of antibody rose continuously from the first sampling at age 1–4 months (mean of differences for Zta, 250 MFI [95% CI, 55.42–443.7; P = .01 (paired t test)]; mean of differences for EAd, 181 MFI [29.50–308 ; P = .03]). The rise in both Zta and EAd IgG from the time of enrollment at 1 month of age suggests ongoing antigenic stimulation from very early in life. The estimated initial levels of Zta-specific IgG at birth did not differ significantly between infants in high- versus low-malaria regions (P = .76), nor did the levels at the time of first sample (P = .78). The stable levels of Zta-specific IgG were also not significantly different (P = .19). However, we found that the expansion rate of Zta-specific IgG was significantly faster for children in the high-malaria region than for those in the low-malaria region (0.4 vs 0.28 month−1; P = .006).

Next, we used the same approach to analyze the kinetics of EAd-specific antibodies, where again we saw no evidence of maternal antibody decay. We found that neither the initial amounts of EAd-specific IgG nor the plateau levels differed significantly between groups (P = .87 and P = .80, respectively). Although there was a trend to faster expansion of antibodies in the high-malaria region (0.4 month−1) compared with the low-malaria region (0.36 month−1), this difference was not significant (P = .38). The summary for both Zta and EAd IgG can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dynamics of Zta- and EAd-Specific IgGa

| Parameter | Value (95% CI) |

P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Malaria Region | High-Malaria Region | ||

| Zta-specific IgG | |||

| Initial level, MFI | 259 (167–350) | 237 (7.8–465) | .76 |

| Expansion rate, mo−1 | 0.28 (.23–.33) | 0.4 (.27–.53) | .006 |

| Threshold level, MFI | 6119 (5224–7015) | 5302 (3200–7405) | .19 |

| EAd-specific IgG | |||

| Initial level, MFI | 352 (175–530) | 375 (72–823) | .87 |

| Expansion rate, mo−1 | 0.365 (.3–.43) | 0.4 (.25–.57) | .38 |

| Threshold level, MFI | 9157 (8047–10 267) | 9172 (6453–11 890) | .80 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EAd, early antigen diffuse complex; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; Zta, EBV Z-transactivation antigen.

a Data from 77 children in Kisumu (high-malaria region) and 86 in Nandi (low-malaria region). We fitted a logistic growth model (see Eq 1, with decay phase removed). Values here are the population parameter estimation of a mixed-effect model; 95% CIs were obtained using the R function intervals in library nlme.

b Significance of differences between high- and low-malaria regions, determined using the Wald test from the nlme package in R.

Kinetics of IgM Response to VCA

In addition to IgG responses, we also measured VCA-specific IgM as a marker of primary infection [13]. The VCA IgM showed a very different trend in overall kinetics, between the low- and high-malaria regions, where no plateau of antibody levels was seen in the high-malaria region (see Figure 1B). We found no evidence for the presence of maternal antibodies as expected. We observed an increasing level of VCA-specific IgM from the first to the second sample (mean of differences in titers between first and second samples is 8.11; 95% CI, 1.91–35.35; P = .01). We used a piecewise log-linear regression to allow for a rising trend, followed by a decline in the level of VCA IgM to model the subsequent kinetics. We found that for children in low-malaria region, VCA IgM rose before a decline around 18 months of age [17–19]. In contrast, we found that the level of VCA IgM for children in the high-malaria region increased to reach a stable level and did not show a subsequent decline. The rate of increase in VCA IgM (from birth until the peak) was significantly higher for children in the high- than for those in the low-malaria region (0.28 vs 0.15 month−1; P < .001). Table 3 shows the summary of the kinetics of anti-VCA IgM levels.

Table 3.

Dynamics of VCA-Specific IgMa

| Parameter | Value (95% CI) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Malaria Region | High-Malaria Region | ||

| Initial level, MFI | 17.6 (10.36–24.9) | 12.95 (3.53–22.36) | .09 |

| Expansion rate, mo−1 | 0.15 (.13–.17) | 0.28 (.19–.38) | <.001 |

| Tlast, mo | 17.9 (17.6–18.1) | 10.4 (9.5–11.3) | <.001 |

| Decay rate, mo−1c | 0.5 (.39–.6) | −0.05 (−.25–.16) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IgM, immunoglobulin M; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; VCA, viral capsid antigen.

a Data from 77 children in Kisumu (high-malaria region) and 86 in Nandi (low-malaria region). We fitted a piecewise model of exponential growth and decay, with Tlast as the transition time. Values here are the population parameter estimation of a mixed-effect model; 95% CIs were obtained using the R function intervals in library nlme.

b Significance of differences between high- and low-malaria regions, determined using the Wald test from the nlme package in R.

c Negative decay rate for high-malaria region is due to the fact that the VCA IgM is continually increasing with a slower rate.

Association Between EBV DNA Detection and Antibody Kinetics

The early rise in antibodies to EBV occurs well before EBV DNA detection, suggesting that individuals have been exposed to EBV for some period before DNA detection. Therefore, we investigated whether the slope of increase in antibody levels was a predictor of time to DNA detection. The expansion rate of VCA-specific IgG was correlated with the time to the first EBV DNA detection, as was the expansion rate of the other antibodies (Table 4). Of note, there is a significant correlation between the estimated expansion in VCA and estimated expansion rate of all the other IgG and IgM antibody levels (P < .05 for all pairwise comparisons; data not shown). Moreover, the decay rates of maternal VCA- and EBNA1-specific IgG were each significantly correlated with the expansion rate of endogenous Zta- and EAd-specific antibodies (P < .001 for all comparisons data not shown).

Table 4.

Predictors of Time to EBV DNA Detection

| Type of Association | Explanatory Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetics of endogenous EBV antibodies and time to EBV DNA detection | Expansion (rise) in VCA IgG | 1.95 (1.06–3.62) | .03 |

| Expansion (rise) in EBNA1 IgG | 2.1 (1.12–3.87) | .02 | |

| Expansion (rise) in Zta IgG | 1.89 (1.15–3.6) | .03 | |

| Expansion (rise) in EAd IgG | 1.48 (1.0–2.18) | .04 | |

| Expansion (rise) in VCA IgM | 1.24 (.94–1.44) | .21 | |

| Decay of maternal antibodies and time to EBV DNA detection | High- vs low-malaria region | 1.32 (.96–1.88) | .08 |

| Initial detectable VCA IgG | 0.55 (.35–.85) | .007 | |

| Decay of VCA IgG | 1.5 (1.05–2.27) | .03 | |

| Initial detectable EBNA1 IgG | 0.52 (.34–.77) | .001 | |

| Decay of EBNA1 IgG | 1.49 (.94–2.36) | .08 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EAd, early antigen diffuse complex; EBNA1, Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HR, hazard ratio; Ig, immunoglobulin; VCA, viral capsid antigen; Zta, EBV Z-transactivation antigen.

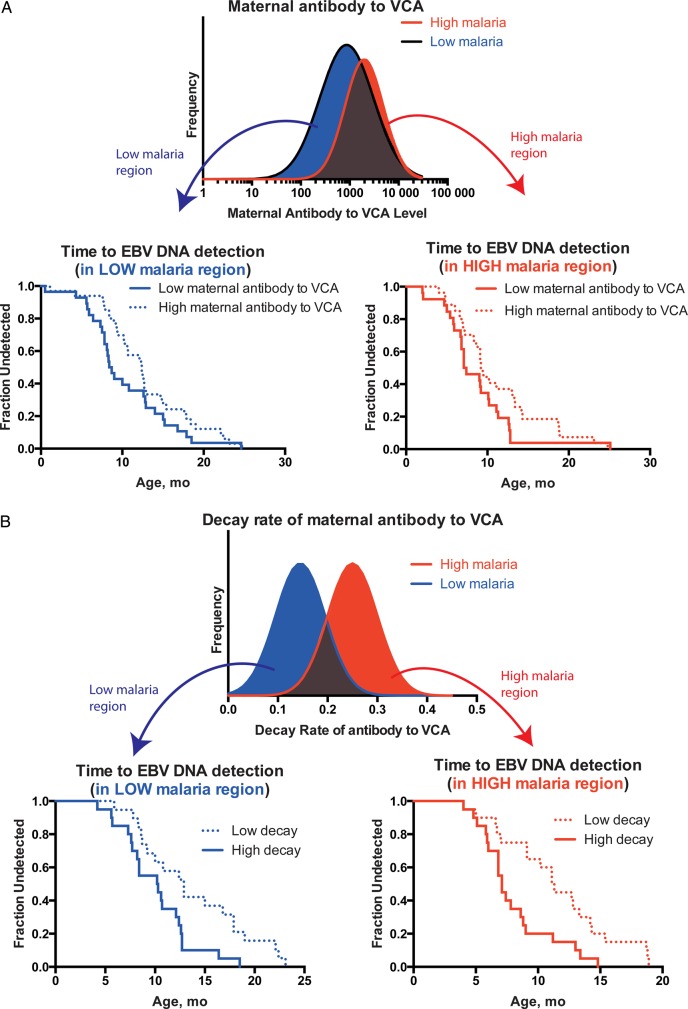

Maternal EBV-Specific Antibody Kinetics in Predicting Time to EBV DNA Detection

Previous work has demonstrated that high malaria exposure is associated with earlier detection of EBV infection (defined by either EBV DNA detection or seroconversion) [5]. The analysis above provides evidence for differences in maternal antibody kinetics and between infants in regions of high and low malaria exposure. In addition, we found a trend for earlier detection of EBV DNA detection in the high-malaria-transmission region (median time to detection, 9.3 months) compared with the low-malaria region (11.3 months; hazard ratio [HR], 1.32); however, this difference was not significant (P = .08).

Next, we investigated whether the kinetic parameters governing maternal antibody dynamics (initial level and the decay slope) were correlated with the time to EBV DNA detection across the cohorts, independent of malaria exposure status. To do this, we used a Cox regression with the initial level of VCA- and EBNA1-specific IgG and the decay slope of these antibodies as the covariates (Table 4). We found that having a higher initial level of maternal antibody is associated with a longer delay to DNA detection (HR, 0.55 [P = .007] for VCA and 0.52 [P = .001] for EBNA1). Moreover, we also observed that having a faster decay rate of maternal antibody is associated with earlier DNA detection (HR, 1.5 [P = .03] for VCA and 1.49 [P = .08] for EBNA1) (Table 4; Figure 2A and 2B). Once these differences in maternal antibody kinetics were taken into account, high versus low malaria exposure was no longer a significant predictor (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Association between antibody kinetics and time to the first of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA detection. A, Survival curves of time to EBV DNA detection is shown for children from the high- and low-malaria regions. In each case, the cohorts are separated according to the initial detectable level of viral capsid antigen (VCA) immunoglobulin G, taking the first half of the children with high level of VCA, and the bottom half of the children with low level of VCA (the halves with highest and lowest levels, respectively). The shortest time to EBV DNA detection occurs in children with low levels of first detectable maternal antibody to VCA in both high- and low-malaria regions. B, Survival curves of time to first DNA detection, separated by rate of decay of maternal EBV antibody to VCA. Here, the shortest time to EBV DNA detection can be observed in children with high decay rates of maternal EBV antibody to VCA.

Although neither initial maternal antibody levels to VCA nor time-to-EBV DNA differ significantly between high- and low-malaria regions, those with high maternal antibody levels had a significantly longer delay to EBV DNA detection (Figure 2A). Similarly, maternal antibody decay rates differed between high- and low-malaria regions, but even within each region, those with faster maternal antibody decay showed earlier time to detection of EBV DNA (Table 4 and Figure 2B). Thus, maternal antibody kinetics seems to be a major factor in determining EBV infection.

DISCUSSION

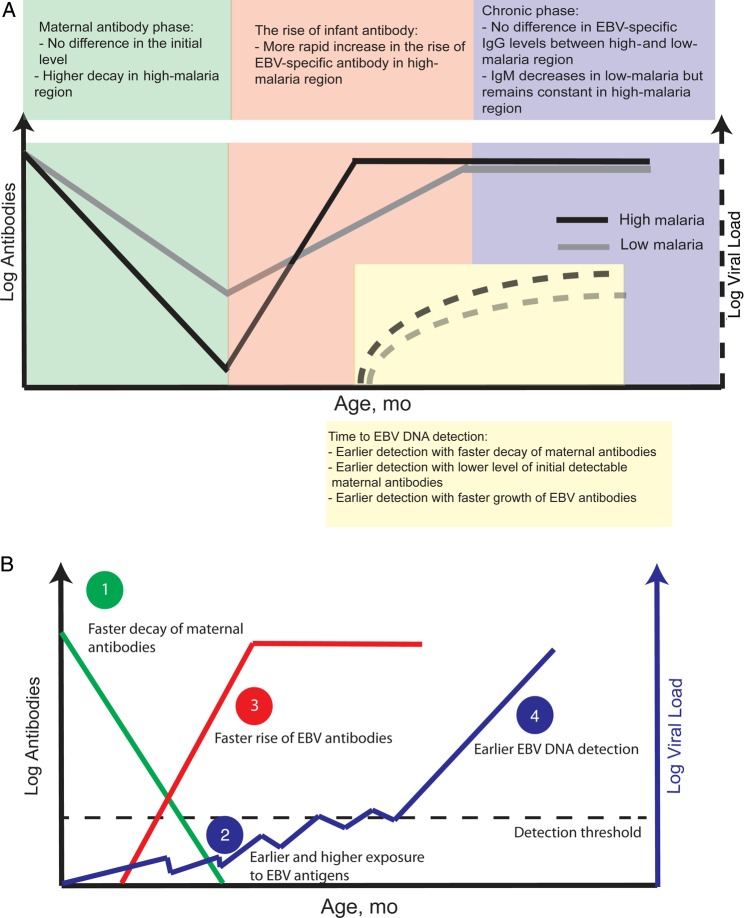

Residence in a high-malaria region was associated with a faster decay of EBV-specific maternal antibody, as well as a more rapid rise in endogenous antibody to VCA- and EBNA1-specific IgG. This more rapid rise was also seen for responses in which no initial decay of maternal antibody was detected (eg, Zta- and EAd-specific IgG) or transplacentally transferred from the mother (eg, VCA-specific IgM).

In this study, we observed 2 very distinct patterns of VCA IgM kinetics. In children infected with EBV in the low-malaria area, VCA IgM follows the classic pattern of increase after infection with a subsequent decline over time. In contrast, in children from the high-malaria region, VCA-specific IgM remains at a high level without waning (Figure 1B). This persistent IgM response has also been observed in patients with chronic hepatitis C [20] and those with persistent human cytomegalovirus [21]. The pattern of VCA IgM detection coincident with EBNA1 IgG has been suggested to be more typical of viral reactivation [22]. This is consistent with our earlier observations of evidence of viral reactivation in children from a malaria-endemic region [12], but in our study, this indicates that EBV reactivation is occurring much earlier in life. An alternative hypothesis for the sustained levels of VCA IgM is that there are multiple primary infections with different EBV types.

Findings of previous studies investigating the impact of malaria infection on the transfer of maternal antibodies have suggested that transfer is reduced in the presence of placental malaria [23, 24]. In our study, we did not have data on maternal malaria exposure, other than as an ecological variable (living in a high- or low-transmission region), and we did not observe a significant difference in either antibody levels detected at first sampling or predicted antibody levels at birth (extrapolating from the later decay curves; Table 1) according to region. However, we found evidence that initial maternal antibody level and the rate of decay of antibody were important determinants of time to EBV DNA detection in infants.

The early rise in antibodies to multiple EBV antigens in the first months of life suggests exposure to EBV infection in early infancy. Previous studies have suggested that seroconversion [3, 25] and detection of DNA [5, 26] do not usually occur until after 6 months of age. The definition of seroconversion may provide somewhat of a barrier here, because, in the case of EBNA1- and VCA-specific IgG, initial seroconversion may be masked by the presence of maternal antibodies. However, for Zta- and EAd-specific IgG, there is evidence of rising antibody levels between the first and second samples. If seroconversion is defined as a rise in antibody titer, then the majority of patients would seroconvert between the first and second measurements. Interestingly, although one might imagine that an indolent and virologically silent infection or transient antigenic exposure in early life may drive these antibody responses, the early responses are by no means slow. Indeed, the fastest rate of increase in antibody responses typically occurs very early after the initial detection.

In addition to seroconversion, the time of actual infection may also be difficult to define. One tends to think of infection as involving active replication of virus. The rising antibody levels to VCA or Zta suggest exposure to lytic-cycle antigens. However, is this exposure to antigens (virus) without actual infection? Or is it very low levels of persistent infection? “Infection,” in this context, could mean abortive rounds of active viral replication (neutralized by maternal antibodies), with or without the persistence of latently infected cells. Thus, the EBV DNA detected after 6 months may be seeded either by a new transmission event or through reactivation of latently infected cells seeded earlier.

Previous work showed a relationship between the nadir in antibody responses (assumed to reflect the last detection of maternal antibody) and detection of infection (by either seroconversion or DNA detection) [5]. Because the last detection of maternal antibody is determined by initial level, decay rate, and rise in endogenous antibody levels, we further dissected these factors. Living in a high-malaria region is associated with a faster decay of maternal antibodies and a higher expansion rate of endogenous EBV antibodies (see Figure 3A). The rate of decay of the 2 maternal antibody responses is correlated within an individual, as is the rate of rise of the endogenous responses to multiple antigens (which are in turn associated with the decay of maternal antibodies).

Figure 3.

Dynamics of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibodies and EBV DNA detection. A, Summary of findings on the differences in the kinetics of EBV-specific antibody responses and EBV DNA detection between regions of high and low malaria exposure. Ig, immunoglobulin. B, Outline of one possible mechanistic association between high malaria exposure and serological and viral dynamics in EBV infection.

Our analysis of associations cannot identify mechanisms and causality. However, the temporal sequence of events and known biological mechanisms make it tempting to speculate as to the processes leading to earlier DNA detection (Figure 3B). For example, if high malaria exposure leads to more rapid maternal antibody decay, this might allow earlier and/or higher levels of EBV exposure or infection in early life, which may in turn drive a faster rise in endogenous antibody responses and lead to detection of EBV DNA at a younger age (summarized in Figure 3B). This hypothesis is supported by our earlier observations that the rate of rise in EBV DNA was also faster in the high-malaria region [6].

Overall, our analysis of the development of the serological response to EBV in early life shows clear differences according to level of exposure to malaria. These differences are evident from the first few months of life, when more rapid maternal antibody decay and more rapid rise in endogenous antibody responses are detectable. Further work is clearly required to confirm these observations and ascertain which of these associations, if any, may be mechanistically linked.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (grant R01 CA134051 to A. M. M. and grant R01 CA102667 to R. R.) and by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) (senior research fellowship APP1080001 to M. P. D.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:481–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facer CA, Playfair JH. Malaria, Epstein-Barr virus, and the genesis of lymphomas. Adv Cancer Res 1989; 53:33–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biggar RJ, Henle W, Fleisher G, Bocker J, Lennette ET, Henle G. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infections in African infants. I. Decline of maternal antibodies and time of infection. Int J Cancer 1978; 22:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moormann AM, Chelimo K, Sumba OP et al. Exposure to holoendemic malaria results in elevated Epstein-Barr virus loads in children. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:1233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piriou E, Asito AS, Sumba PO et al. Early age at time of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection results in poorly controlled viral infection in infants from Western Kenya: clues to the etiology of endemic Burkitt lymphoma. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:906–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Chelimo K et al. Impact of Plasmodium falciparum coinfection on longitudinal Epstein-Barr virus kinetics in Kenyan children. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daud II, Ogolla S, Amolo AS et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection is associated with Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in pregnant women living in malaria holoendemic area of Western Kenya. Matern Child Health J 2015; 19:606–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de-The G, Geser A, Day NE et al. Epidemiological evidence for causal relationship between Epstein-Barr virus and Burkitt's lymphoma from Ugandan prospective study. Nature 1978; 274:756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter LM, Newton R, Casabonne D et al. Antibodies against malaria and Epstein-Barr virus in childhood Burkitt lymphoma: a case-control study in Uganda. Int J Cancer 2008; 122:1319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asito AS, Piriou E, Odada PS et al. Elevated anti-Zta IgG levels and EBV viral load are associated with site of tumor presentation in endemic Burkitt's lymphoma patients: a case control study. Infect Agent Cancer 2010; 5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogolla S, Daud II, Asito AS et al. Reduced transplacental transfer of a subset of Epstein-Barr virus-specific antibodies to neonates of mothers infected with Plasmodium falciparum malaria during pregnancy. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2015; 22:1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piriou E, Kimmel R, Chelimo K et al. Serological evidence for long-term Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in children living in a holoendemic malaria region of Kenya. J Med Virol 2009; 81:1088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison BJ, Labo N, Miley WJ, Whitby D. Serodiagnosis for tumor viruses. Semin Oncol 2015; 42:191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fachiroh J, Paramita DK, Hariwiyanto B et al. Single-assay combination of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) EBNA1- and viral capsid antigen-p18-derived synthetic peptides for measuring anti-EBV immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA antibody levels in sera from nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: options for field screening. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:1459–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moormann AM, Chelimo K, Sumba PO, Tisch DJ, Rochford R, Kazura JW. Exposure to holoendemic malaria results in suppression of Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cell immunosurveillance in Kenyan children. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson P, Beynon S, Whybin R et al. Measurement of EBV-IgG anti-VCA avidity aids the early and reliable diagnosis of primary EBV infection. J Med Virol 2003; 70:617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamy ME, Favart AM, Cornu C, Mendez M, Segas M, Burtonboy G. Study of Epstein Barr virus (EBV) antibodies: IgG and IgM anti-VCA, IgG anti-EA and Ig anti-EBNA obtained with an original microtiter technique: serological criterions of primary and recurrent EBV infections and follow-up of infectious mononucleosis—seroepidemiology of EBV in Belgium based on 5178 sera from patients. Acta Clin Belg 1982; 37:281–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleisher G, Henle W, Henle G, Lennette ET, Biggar RJ. Primary infection with Epstein-Barr virus in infants in the United States: clinical and serologic observations. J Infect Dis 1979; 139:553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans AS, Niederman JC, Cenabre LC, West B, Richards VA. A prospective evaluation of heterophile and Epstein-Barr virus-specific IgM antibody tests in clinical and subclinical infectious mononucleosis: specificity and sensitivity of the tests and persistence of antibody. J Infect Dis 1975; 132:546–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brillanti S, Foli M, Perini P, Masci C, Miglioli M, Barbara L. Long-term persistence of IgM antibodies to HCV in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1993; 19:185–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller TF, Gicklhorn D, Jungraithmayr T et al. Pattern and persistence of the epitope-specific IgM response against human cytomegalovirus in renal transplant patients. J Clin Virol 2002; 24:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nystad TW, Myrmel H. Prevalence of primary versus reactivated Epstein-Barr virus infection in patients with VCA IgG-, VCA IgM- and EBNA-1-antibodies and suspected infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Virol 2007; 38:292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cumberland P, Shulman CE, Maple PA et al. Maternal HIV infection and placental malaria reduce transplacental antibody transfer and tetanus antibody levels in newborns in Kenya. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okoko BJ, Wesumperuma LH, Ota MO et al. The influence of placental malaria infection and maternal hypergammaglobulinemia on transplacental transfer of antibodies and IgG subclasses in a rural West African population. J Infect Dis 2001; 184:627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan KH, Tam JS, Peiris JS, Seto WH, Ng MH. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in infancy. J Clin Virol 2001; 21:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyohas MC, Marechal V, Desire N, Bouillie J, Frottier J, Nicolas JC. Study of mother-to-child Epstein-Barr virus transmission by means of nested PCRs. J Virol 1996; 70:6816–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.