Abstract

Objective:

To investigate depression frequency, severity, current treatment, and interactions with somatic symptoms among patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD).

Methods:

In this dual-center observational study, we included 71 patients diagnosed with NMOSD according to the International Panel for NMO Diagnosis 2015 criteria. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was classified into severe, moderate, or minimal/no depressive state category. We used the Fatigue Severity Scale to evaluate fatigue. Scores from the Brief Pain Inventory and the PainDETECT Questionnaire were normalized to estimate neuropathic pain. Psychotropic, pain, and immunosuppressant medications were tabulated by established classes.

Results:

Twenty-eight percent of patients with NMOSD (n = 20) had BDI scores indicative of moderate or severe depression; 48% of patients (n = 34) endorsed significant levels of neuropathic pain. Severity of depression was moderately associated with neuropathic pain (r = 0.341, p < 0.004) but this relationship was confounded by levels of fatigue. Furthermore, only 40% of patients with moderate or severe depressive symptoms received antidepressant medical treatment. Fifty percent of those treated reported persistent moderate to severe depressive symptoms under treatment.

Conclusions:

Moderate and severe depression in patients with NMOSD is associated with neuropathic pain and fatigue and is insufficiently treated. These results are consistent across 2 research centers and continents. Future research needs to address how depression can be effectively managed and treated in NMOSD.

Depression is one of the most common and debilitating comorbidities of neurologic diseases. It has been associated with decreased quality of life, lower treatment adherence rate, increased disease severity, higher unemployment rates, and cognitive deficits among neurology patients.1 Depression is also exacerbated by symptoms of fatigue2 and pain,3 the interaction of which has a direct effect on quality of life.

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an autoimmune disease of the CNS associated with serum antibodies to the astrocyte water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4).4 NMOSD is predominantly characterized by optic neuritis and transverse myelitis leading to blindness, weakness, numbness, and pain.5 Brain areas typically associated with organic depression,6,7 such as prefrontal areas, limbic systems, and the hippocampus, are usually spared among patients with NMOSD.8–10 However, recent studies have reported a high prevalence of depression within this population and have claimed that patients with NMOSD present with depression severity comparable to that experienced by patients with multiple sclerosis.11–13 Due to the low prevalence of NMOSD,14,15 previous studies have employed smaller samples and international comparisons are currently missing. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the elements of depression among patients with NMOSD within a larger multicenter cohort.

We assessed the frequency and severity of depressive states and their interaction with somatic symptoms in a multicenter observational investigation across 2 continents. Our secondary objective was to evaluate the association of disease-modifying, pain, and psychotropic therapy with current depressive and somatic symptoms.

METHODS

Sample.

We collected data in a cross-sectional observational study at 2 major academic research centers: the Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany (the Charité) and the Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHU), Baltimore, MD.

Inclusion criteria were formal diagnosis of NMOSD according to the International Panel for NMO Diagnosis 2015 updated diagnostic criteria16 and conversational level of the primary language spoken at the recruiting center. Exclusion criteria were age over 70 years and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody seropositivity when available.17 All patients at each center who satisfied the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria were included in this study.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Study initiation followed research protocol approval by the internal ethics review board at each institution. Patients provided written informed consent and underwent a formal neurologic examination.

Assessment of depressive symptomatology.

To evaluate depressive symptoms, we administered the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)–IA18 at the Charité and BDI-II version19 at JHU. Both versions contain 21 questions with a maximum total score of 63. Total BDI-IA scores were adjusted to BDI-II scores according to the BDI-II Manual.20 We interpreted BDI scores as follows: 0–9 as nondepressive affect; 10–19 as minimal mood disturbance; 20–29 as moderate depressive state; 30 and above as severe depressive state.20 Consistent with prior literature, we categorized patients whose total BDI score was ≥20 with a high likelihood of clinical depression.21,22

Assessment of fatigue.

We assessed fatigue with the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS).23 This questionnaire measures severity of fatigue in 9 questions on a 7-point Likert scale. A threshold level of 4 has been shown to differentiate individuals with and without significant levels of fatigue.2,23,24

Neuropathic pain.

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and the PainDETECT Questionnaire (PDQ) were used to evaluate presence and severity of pain at JHU and the Charité, respectively.

The BPI was created to measure pain level from 0 (least) to 10 (worst) in cancer patients in the United States.25 Among patients with nonmalignant chronic pain, an average BPI score of 6.8 (SD 1.8) has been reported26 and recent work has shown that patients with NMO average a BPI score of 5.9 (SD 2.9).27 Based on these findings, we adopted a conservative cutoff score of 6: patients who scored <6 on the BPI index were classified as not having pain with a significant neuropathic component while those scoring ≥6 were classified as experiencing neuropathic pain. Although a conservative cutoff score of BPI = 6 may have decreased sensitivity of this measure, it minimized overestimating the prevalence of neuropathic pain.

The PDQ was created to differentiate nociceptive from neuropathic pain in low back pain patients.28 According to validation data representative of the German population,26 a PDQ score of 12 or higher is indicative of pain with a primarily neuropathic etiology. We classified individuals with scores ≥12 as experiencing neuropathic pain, and those with scores <12 as not experiencing pain with a substantial neuropathic component.

To allow for a quantitative comparison of pain within the entire cohort, we tested the distribution of BPI and PDQ scores for normality with Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests and standardized individual values to the mean of their respective recruiting center sample. After pooling, z scores of pain levels used in all statistical tests ranged from −1.68 to 2.085 (mean −0.0001, SD 0.993), representing average and SD of pain within our cohort.

Current pharmacotherapy.

We recorded immunosuppressive preventive therapy for NMOSD, including rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate, and methotrexate.29,30 Pain medications included anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, clonazepam, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, zonisamide), muscle relaxants (baclofen, tizanidine, diazepam, dantrolene, tolperisone), tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline), opioids (tramadol, fentanyl, oxycodone), and a selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI; duloxetine). The nature and etiology of pain reported by patients with NMOSD is often managed with multiple medication categories, most frequently with anticonvulsants and low-dose tricyclic antidepressants.31–33 Psychoactive medications included SNRI (duloxetine, venlafaxine, milnacipran), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI; citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline), tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline), and atypical antidepressants (mirtazapine).

Statistical analyses.

We examined the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with BDI ≥20 and those with BDI <20. Continuous variables between groups were compared with independent samples t tests; categorical variables, with Pearson χ2 tests; effect sizes are reported with Cohen d. Distributions of all outcome variables were assessed for normality with Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Nonparametric tests were used to assess non-normally distributed continuous outcomes, ordinal variables, and the effect of treatment on the primary outcomes. We performed Pearson correlations of primary outcomes and partial correlations adjusting for confounders. We utilized a stepwise multiple regression to evaluate the variability of BDI scores attributable to somatic symptoms and clinical and demographic factors. All tests were 2-tailed and significance was indicated when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographics.

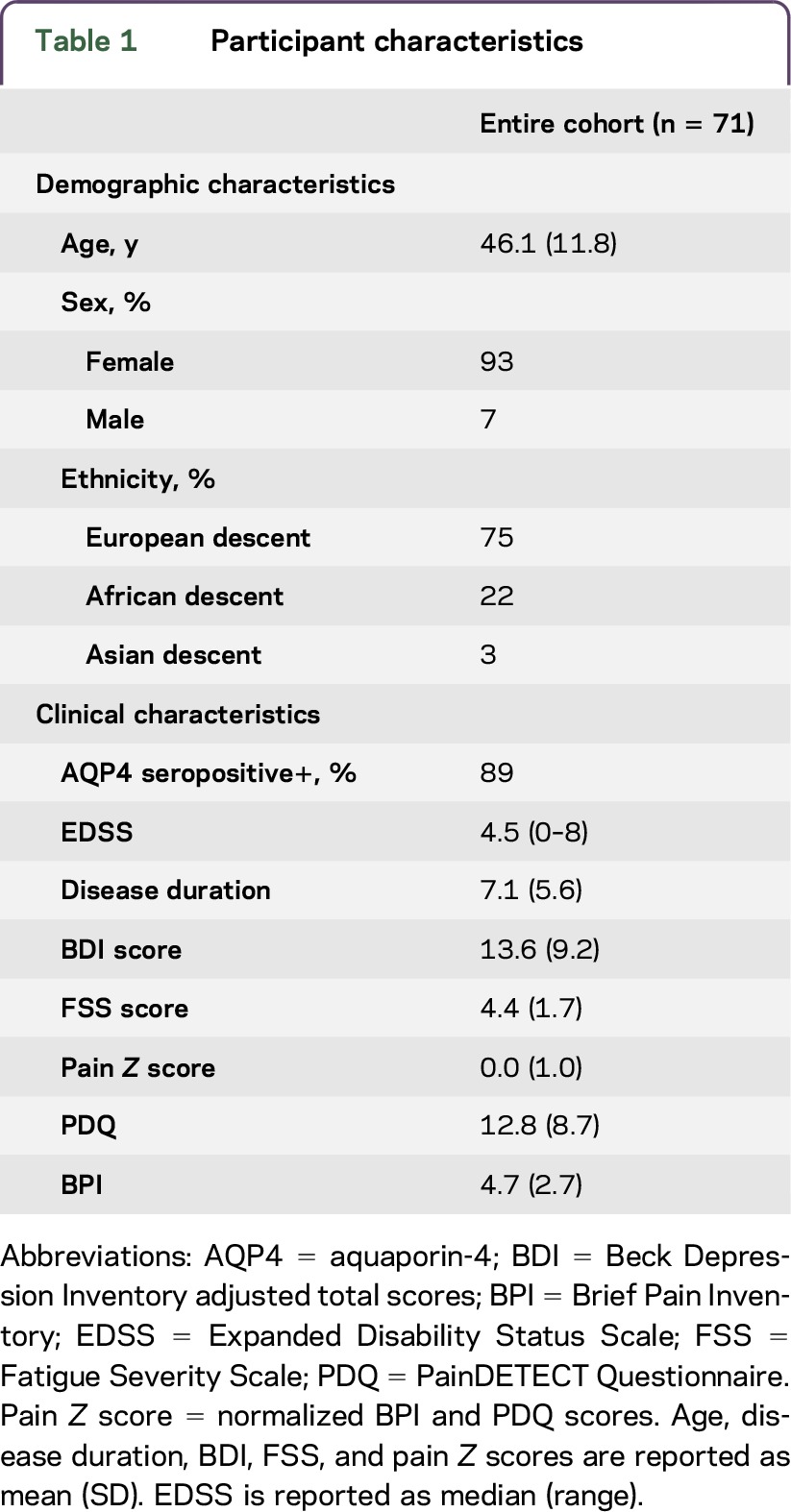

Seventy-one patients with NMOSD (n = 36 at JHU, n = 35 in Berlin), 89% of whom were AQP4-positive, were enrolled in this study. Ninety-three percent of all participants were female; the female to male ratio was typical of relapsing NMOSD.9 The mean disease duration was 7.1 years (SD 5.6) and the median Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) of the sample was 4.5 (range 0–8). Participants did not differ on demographic and clinical variables between centers, except on ethnic distribution and EDSS. Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of the entire cohort and clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample by recruitment center are shown in table e-1 at Neurology.org/nn.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

Frequency of moderate or severe depression.

We found that 30% (n = 21) of patients with NMOSD scored between 10 and 19, consistent with a dysphoric state; 22% (n = 16) scored between 20 and 29, consistent with moderate depressive state; and 6% (n = 4) scored above 30, consistent with severe depression. Fifteen patients with NMOSD (21%) also endorsed suicidal ideation or behavior, indicated by a score of 1 or greater on item 9 of the BDI. Seventy-five percent of patients who reported suicidal ideation or behavior scored 20 or greater and the distribution of suicidal patients did not differ across centers.

Patients with BDI scores ≥20 and patients with BDI scores <20 did not differ with regard to age (mean 47.1, SD 11.1 vs mean 45.7, SD 12.2, p > 0.1), disease duration (mean 5.7, SD 4.2 vs mean 7.7, SD 5.3, p > 0.1), or EDSS (median 5.5, 1–7 vs median 4.0, 0–8, U = 421.5, p > 0.1). Distribution of BDI scores was similar across the 2 recruiting centers. The figure illustrates the severity of depressive symptoms by center (A) and antidepressant treatment (B).

Figure. Depression severity.

(A) Labeled by recruiting center. (B) Labeled by antidepressant medication therapy. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; JHU = Johns Hopkins Hospital; SNRI = serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

History and relapse rate of optic neuritis (ON), transverse myelitis (TM), or both ON and TM was available only for the cohort from the Charité. BDI scores between patients with any of the 3 classifications (ON, TM, or ON and TM) did not differ, F = 0.667, p = 0.520. Furthermore, relapse rate was not associated with BDI scores, Pearson r(26) = 0.212, p = 0.297. The 6 patients with monophasic disease had an average BDI score mean = 14.5 (SD 9.1), which was not different from the entire cohort mean.

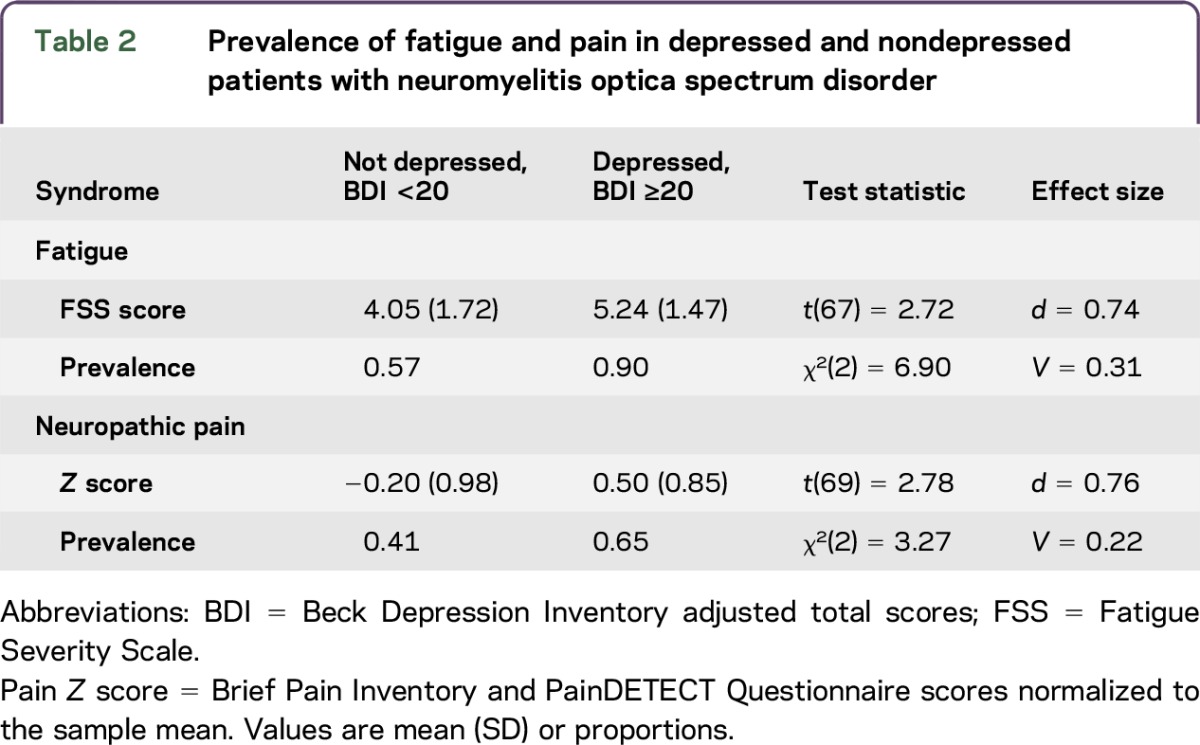

Depression associated with higher levels of fatigue and neuropathic pain.

Patients with moderate to severe depressive states had significantly higher FSS scores than patients with mild or minimal depressive states and experienced neuropathic pain of greater intensity. With the exception of one patient, all who scored 20 or greater on the BDI had elevated FSS scores (table 2). BDI scores were moderately correlated with standardized pain scores, Pearson r(71) = 0.341, p < 0.004. However, when fatigue was controlled for, this association became weaker, Pearson r(66) = 0.140, p = 0.254.

Table 2.

Prevalence of fatigue and pain in depressed and nondepressed patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

In a multiple regression model, pain and fatigue accounted for 23% of the variance in depressive states, R2 = 0.23, F2,66 = 9.67, p < 0.001. Demographic or clinical parameters, including EDSS, did not contribute to explaining the variance of depressive states beyond pain and fatigue. Of note, lower disease duration (β = −0.247, p = 0.244) and greater EDSS (β = 0.772, p = 0.271) were associated with an increase in BDI score.

Somatic symptoms and prescription medication therapy.

Of the 68 participants who provided information on antidepressant medications, a total of 20 patients received antidepressant pharmacotherapy, either as psychiatric or pain therapy. There was no difference in the distribution of antidepressant medications reported by patients across centers, Pearson χ2(3,68) = 5.896, p = 0.117. Table e-2 presents the distribution of medications by center. Fifty percent of those (10 out of 20) still scored 19 or above on the BDI and only 4 scored within the normal range of BDI. Medically treated patients were 40% (8 out of 20) of the total number of patients with BDI score ≥20. Half of the patients categorized as severely depressed (2 out of 4), based on a BDI score above 30, received antidepressant medication therapy. A total of 6 out of 16 patients with moderate depression received antidepressant therapy. Among patients who reported moderate depression, antidepression medications included tricyclics (n = 3), atypical antidepressants (n = 2), and SNRI (n = 1); 3 of these patients were receiving antidepressants for the indication of pain and not depression.

Fifty-two percent of patients received pain medication therapy (36 out of 69), the majority (56%, 20 out of 36) filling current prescriptions for more than one category of pain medication. Of note, the distribution of pain medications differed across recruiting centers, Pearson χ2(3,69) = 11.887, p = 0.018 (table e-2). Twenty-five percent (9 out of 36) were taking only anticonvulsants, 17% (6 out of 36) were taking only muscle relaxants, and 1 patient was prescribed the opioid/SNRI tramadol. All patients who received low-dose antidepressants as indicated for pain treatment were also receiving other classes of pain medications. Among patients with NMOSD prescribed any pain medications, 58% (21 out of 36) still endorsed current pain above the threshold for clinically significant neuropathic pain (PDQ >12 and BPI >6).

Patients who receive pain medications and no psychopharmacotherapy have lower depressive states and fatigue.

Patients who received only pain therapy scored almost 8 points lower on the total BDI score (mean 10.26, SD 5.32, n = 19) than those who received both psychotropic and pain medications (mean 18.00, SD 10.78, n = 16, t[33] = 2.614, p = 0.016, d = 0.911). Patients who took low-dose antidepressants indicated for pain treatment were included in the pain and antidepressants medications group. The category of psychopharmacologic therapy did not have an effect on BDI scores stratified by pain medication. Further, among the 16 patients who received both psychotropic and pain medications, half had a BDI score >20, in comparison to only 2 among the 19 patients who received only pain medications.

Patients with NMOSD who received only pain therapy had lower fatigue scores (mean 4.47, SD 1.78, n = 19) than patients who received both pain and psychoactive medications (mean 4.60, SD 1.70, n = 16) and patients who received only psychotropic medications (mean 4.95, SD 1.19, n = 4). In comparison, patients with NMOSD who received neither pain nor psychoactive medications had an average FSS score mean 4.00, SD 1.70, n = 27. This difference in fatigue scores did not reach significance.

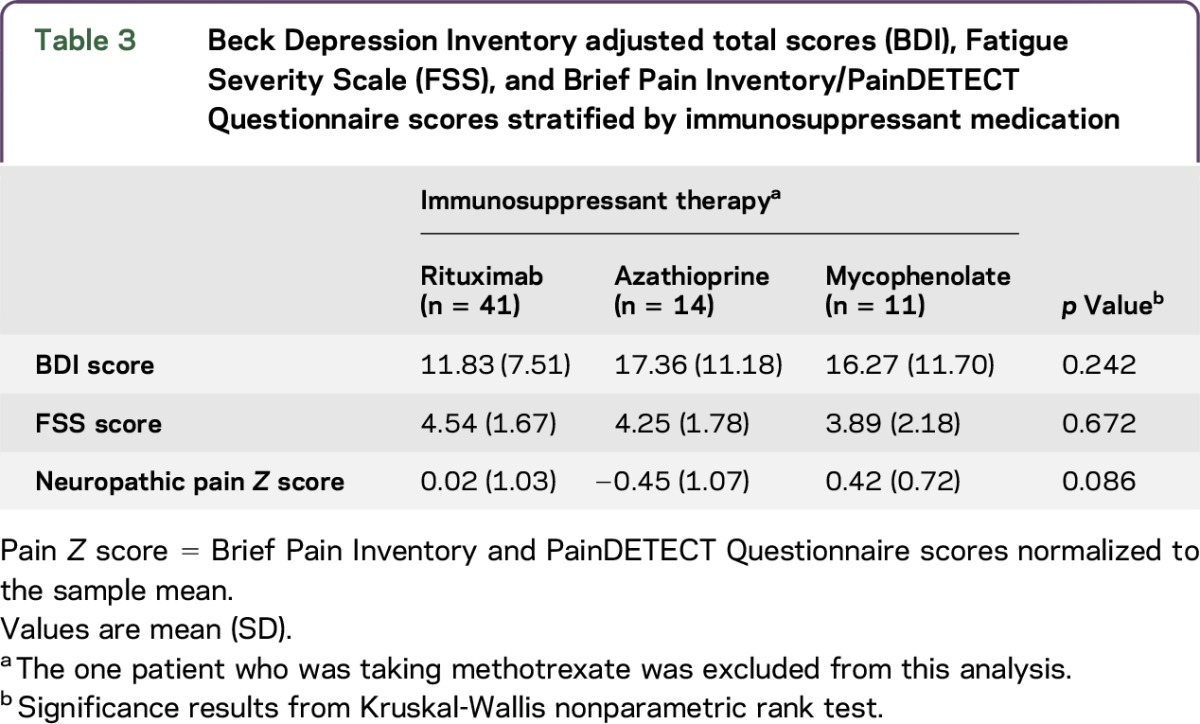

Immunosuppressive therapy is differentially associated with depression, fatigue, and pain.

When stratified by current immunosuppressant therapy, patients who were treated with rituximab scored lowest on the BDI (mean 11.83, SD 7.51, n = 41) compared to patients who received mycophenolate (mean 16.27, SD 11.70, n = 11) and patients receiving azathioprine (mean 17.13, SD 11.18, n = 14). A nonparametric test of rank differences did not reach significance. Additionally, across patients who received rituximab, BDI scores were similar regardless of pain or psychotropic medications. Table 3 illustrates pain, fatigue, and depression levels tabulated by immunosuppressant medication.

Table 3.

Beck Depression Inventory adjusted total scores (BDI), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), and Brief Pain Inventory/PainDETECT Questionnaire scores stratified by immunosuppressant medication

DISCUSSION

In this transnational comparison of depressive symptomatology in NMOSD, moderate to severe depression was observed in 28% of patients. Our results exhibit a consistency of depressive and somatic symptomatology across 2 research centers and continents. We observed no significant differences in the prevalence or severity of depression, fatigue, or pain between patients in Germany and patients in the United States. These findings are in line with recent research from the United Kingdom, France, and Japan.20,22,34

As established in cohorts with major depression, suicidality was the most common symptom associated with high scores on the BDI.35,36 Prevalence and severity of BDI scores were not associated with history of myelitis or optic neuritis. Further, within our sample, patients with moderate to severe depression had significantly higher levels of pain and fatigue than patients with NMOSD with no or minimal depressive symptoms. Similar findings are also reflected in previous studies largely demonstrating a positive correlation between pain and depressive affect3,37,38 as well as between fatigue and depressive affect.39,40,e1

Although pain is moderately and significantly correlated with depression among patients with NMOSD, levels of fatigue account for the majority of this association. Interestingly, physical disability or disease duration did not contribute significantly to the variance of depressive states. This provides further evidence for pain as antecedent to depression proposed by Fishbain et al.3 Our study design prevents us from showing a causal relationship; however, when stratified by immunosuppressant therapy, we observed that BDI scores are high when levels of pain and fatigue are inversely related. This may indicate that the interaction of fatigue and pain is differentially modulated by immunosuppressant therapy and specifically contributes to depressive mood in this cohort.

We also show that despite receiving antidepressant medications, half of patients with NMOSD still scored 20 or above on the BDI, suggesting insufficient or inadequate management of depressive symptomatology. Interestingly, we observed that if taken concurrently with pain medications, antidepressant medication therapy is associated with significantly higher BDI scores. Although these results must be interpreted with caution due to our small sample sizes, they may suggest that patients who experience only pain, and therefore take only pain medications, report lower depression levels. However, when depressive states are comorbid with pain, the additional burden appears not adequately alleviated despite multiple classes of pharmacotherapy.

Prescriptions of pain medications vary greatly among patients taking different disease-modifying therapies. However, there were no statistically significant differences in depression severity among patients treated with different disease-modifying therapies. The cross-sectional design of our study does not allow us to infer whether immunosuppressant, pain, and depression therapy specifically affect depressive symptoms, fatigue, or pain. Future research should address the specifics of these interactions with larger cohorts in longitudinal or randomized case-control studies.

Our study had some limitations. First, we utilized different versions of the BDI in each research center. BDI-IA probes for responses pertaining to the past week and BDI-II probes for responses pertaining to the past 2 weeks. We adjusted the total scores of BDI-IA to those of BDI-II as recommended by Beck et al.20 and used only the adjusted BDI scores in our analyses. We selected a conservative cutoff score of 20 to classify individuals as depressed. In line with current research and clinical recommendations, we define depression as a syndrome of affective and psychosomatic symptoms, and do not imply a diagnosis of major depressive disorder.e2,e3

Another limitation was the use of different scales to measure pain at each center. The PDQ and the BPI are similar as both measure severity and frequency of neuropathic pain. However, the former captures pain within the past 4 weeks, while the latter captures pain within the last 24 hours. This was an inherent weakness in the design of our study, which we addressed by normalizing PDQ and BPI scores to allow for comparison of pain levels within our cohort. Further, we could not control for preexisting depression or other therapies, such as psychotherapy, and did not have information on duration of treatment with antidepressants. All of these important factors would affect the interpretation of our results.

In the current study, we report that 28% of patients with NMOSD present with moderate to severe depressive symptomatology, which is substantially above the global estimated rate of 5.5%–5.9% of depression in the general populatione3 and is comparable to the 23.7% (confidence interval 17.4%–30%) prevalence rate of depression observed among patients with multiple sclerosis.e4 Moreover, we observed that the majority of patients who report depressive symptoms indicative of moderate to severe depressive states do not receive appropriate antidepressant pharmacotherapy, suggesting insufficient or inadequate management of depressive symptomatology among patients with NMOSD. We also show that disease-modifying and pain therapy may modulate levels of depressive symptomatology, and suggest that fatigue and pain may confound this interaction. Future prospective and longitudinal studies with larger cohorts are needed to support our results.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AQP4

aquaporin-4

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- BPI

Brief Pain Inventory

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- FSS

Fatigue Severity Scale

- JHU

Johns Hopkins Hospital

- NMO

neuromyelitis optica

- NMOSD

neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

- ON

optic neuritis

- PDQ

PainDETECT Questionnaire

- SNRI

serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- TM

transverse myelitis

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/nn

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/nn

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: F. Paul, A.U. Brandt, M. Levy. Acquisition of data: M.A. Mealy, A. Simpson, A. Lacheta, F. Pache. Analysis and interpretation: V.S. Chavarro, M.A. Mealy, F. Paul, A.U. Brandt, M. Levy. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: V.S. Chavarro, M.A. Mealy, A. Simpson, A. Lacheta, F. Pache, K. Ruprecht, S.M. Gold, F. Paul, A.U. Brandt, M. Levy. Study supervision: K. Ruprecht, F. Paul, A.U. Brandt, M. Levy.

STUDY FUNDING

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Exc 257 to F. Paul and V.S.C. and GO1357/5-2 to S.M.G.) and Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Competence Network Multiple Sclerosis) to S.M.G., F.P., F. Pache, and K.R.

DISCLOSURE

V. Chavarro received research support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. M.A. Mealy received speaker honoraria from Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. A. Simpson and A. Lacheta report no disclosures. F. Pache received travel funding from Genzyme, Bayer, Biogen Idec, and ECTRIMS. K. Ruprecht served on the scientific advisory board for Sanofi-Aventis/Genzyme, Novartis, and Roche; received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis/Genzyme, Teva, Novartis, and Guthy Jackson Charitable Foundation; is an academic editor for PLoS One; received royalties from Elsevier; and received research support from the German Ministry of Education and Research. S.M. Gold consulted for UCLA and Cedars Sinai Medical Center and received research support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. F. Paul served on the scientific advisory board for Novartis and MedImmune; received speaker honoraria and travel funding from Bayer, Novartis, Biogen Idec, Teva, Sanofi-Aventis/Genzyme, Merck Serono, Alexion, Chugai, MedImmune, and Shire; is an academic editor for PLoS One and an associate editor for Neurology® Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation; has consulted for SanofiGenzyme, Biogen Idec, MedImmune, Shire, and Alexion; and received research support from Bayer, Novartis, Biogen Idec, Teva, Sanofi-Aventis/Genzyme, Alexion, Merck Serono, German Research Council, Werth Stiftung of the City of Cologne, German Ministry of Education and Research, Arthur Arnstein Stiftung Berlin, EU FP7 Framework Program, Guthy Jackson Charitable Foundation, and National Multiple Sclerosis Society of the USA. A.U. Brandt served on the scientific advisory board for Biogen; received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Novartis, Bayer, Biogen, and Teva; has a patent pending for method and system for optic nerve head shape quantification, perceptive visual computing based postural control analysis, multiple sclerosis biomarker, and perceptive sleep motion analysis; has consulted for Nexus and Motognosis; received research support from Novartis, Biogen Idec, BMWi, and BMBF; and holds stock or stock options in Motognosis. M. Levy served on the scientific advisory board for Asterias, Chugai, and Alexion; is on the editorial board for Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders; holds a patent for Aquaporin-4 sequence that elicits pathogenic T cell response in animal model of neuromyelitis optica; has consulted for Guidepoint Global, Gerson Lehrman Group, and Cowen Group; and received research support from Viropharma/Shire, Acorda, ApoPharma, Sanofi, Genzyme, Alnylam, Alexion, Terumo BCT, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and Guthy Jackson Charitable Foundation. Go to Neurology.org/nn for full disclosure forms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raskind MA. Diagnosis and treatment of depression comorbid with neurologic disorders. Am J Med 2008;121(11 suppl 2):S28–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Miletich RS, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis and its relationship to depression and neurologic disability. Mult Scler 2000;6:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain 1997;13:116–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zekeridou A, Lennon VA, Zamvil SS, Slavin AJ. Aquaporin-4 autoimmunity. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation 2015;2:e110. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarius S, Wildemann B, Paul F. Neuromyelitis optica: clinical features, immunopathogenesis and treatment. Clin Exp Immunol 2014;176:149–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Phillips ML. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet 2012;379:1045–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kempton MJ. Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:675–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: an international update. Neurology 2015;84:1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Wildemann B, et al. Contrasting disease patterns in seropositive and seronegative neuromyelitis optica: a multicentre study of 175 patients. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pekcevik Y, Orman G, Lee IH, Meally MA, Levy M, Izbudak I. What do we know about brain contrast enhancement patterns in neuromyelitis optica? Clin Imaging 2016;40:573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore P, Methley A, Pollard C, et al. Cognitive and psychiatric comorbidities in neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Sci 2016;360:4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanson JB, Zéphir H, Collongues N, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life, fatigue and depression in neuromyelitis optica. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:836–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawahara Y, Ikeda M, Deguchi K, et al. Cognitive and affective assessments of multiple sclerosis (MS) and neuromyelitis optica (NMO) patients utilizing computerized touch panel-type screening tests. Intern Med 2014;53:2281–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mealy MA, Wingerchuk DM, Greenberg BM, Levy M. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica in the United States. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1176–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandit L, Asgari N, Apiwattanakul M, et al. Demographic and clinical features of neuromyelitis optica: a review. Mult Scler 2015;21:845–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2015;85:177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamvil SS, Slavin AJ. Does MOG Ig-positive AQP4-seronegative opticospinal inflammatory disease justify a diagnosis of NMO spectrum disorder? Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation 2015;2:e62. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck A, Steer R. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck A, Steer R, Ball R, Ranieri W. BDI Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 1996;67:588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory Manual, 2nd ed Bloomington, IN: PsychCorp Pearson Clinical Assessment; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol 2001;20:112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprinkle SD, Lurie D, Insko SL, et al. Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. J Couns Psychol 2002;49:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krupp L, LaRocca N, Muir-Nash J, et al. The Fatigue Severity Scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989;46:1121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flachenecker P, Kümpfel T, Kallmann B, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of different rating scales and correlation to clinical parameters. Mult Scler 2002;8:523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daut R, Cleeland C, Flanery R. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to asses pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 1983;17:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain 2004;5:133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao S, Mutch K, Elsone L, Nurmikko T, Jacob A. Neuropathic pain in neuromyelitis optica affects activities of daily living and quality of life. Mult Scler 2014;20:1658–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. PainDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1911–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimbrough DJ, Fujihara K, Jacob A, et al. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica: review and recommendations. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2012;1:180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trebst C, Jarius S, Berthele A, et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica: recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). J Neurol 2014;261:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian P, Lancia S, Alvarez E, Klawiter EC, Cross AH, Naismith RT. Association of neuromyelitis optica with severe and intractable pain. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1482–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SM, Go MJ, Sung JJ, Park KS, Lee KW. Painful tonic spasm in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol 2012:69:1026–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connor AB, Dworkin RH. Treatment of neuropathic pain: an overview of recent guidelines. Am J Med 2009;122:S22–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones JE, Hermann BP, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Kanner AM, Meador KJ. Clinical assessment of axis I psychiatric morbidity in chronic epilepsy: a multicenter investigation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;17:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Steer RA, Beck JS, Newman CF. Hopelessness, depression, suicidal ideation, and clinical diagnosis of depression. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1993;23:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck T, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B. Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Korff M, Simon G. The relationship between pain and depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996:101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visser MR, Smets EM. Fatigue, depression and quality of life in cancer patients: how are they related? Support Care Cancer 1998;6:101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalgas U, Stenager E, Jakobsen J, et al. Fatigue, mood and quality of life improve in MS patients after progressive resistance training. Mult Scler 2010;16:480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.