Abstract

Summary: We present ChAsE, a cross-platform desktop application developed for interactive visualization, exploration and clustering of epigenomic data such as ChIP-seq experiments. ChAsE is designed and developed in close collaboration with several groups of biologists and bioinformaticians with a focus on usability and interactivity. Data can be analyzed through k-means clustering, specifying presence or absence of signal in epigenetic data and performing set operations between clusters. Results can be explored in an interactive heat map and profile plot interface and exported for downstream analysis or as high quality figures suitable for publications.

Availability and Implementation: Software, source code (MIT License), data and video tutorials available at http://chase.cs.univie.ac.at.

Contact: mkarimi@brc.ubc.ca or torsten.moeller@univie.ac.at

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Epigenetics is the study of changes in the regulation of gene activity and expression that are not dependent on gene sequence. Advances in DNA sequencing technology have enabled researchers to investigate the epigenetic state of cells by profiling modifications such as histone methylation across the whole genome using techniques such as chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq). While computational methods to interpret ChIP-seq data continue to evolve and improve, many questions cannot be easily addressed in an automated fashion, and biologists need to be engaged directly in data processing and interpretation.

Several techniques such as ChromaSig (Hon et al., 2008) and ChromHMM (Ernst and Kellis, 2010) use probabilistic methods for the discovery of epigenetic signatures, but often require significant computational skill to use. Platforms such as Cistrome (Liu et al., 2011) and SeqMonk (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/seqmonk) provide a tool chain of diverse analysis methods and graphical interfaces for improved usability; however, they offer limited interactivity and visualization. Genome browsers such as the WashU Epigenome Browser (Zhou et al., 2011) are popular interactive visualization tools that plot data along a reference genome coordinate and display epigenomic marks as separate tracks vertically stacked to facilitate comparison. Local regions can be viewed one-at-a-time, but obtaining an overview of global data patterns can be challenging. More recently, Epiviz (Chelaru et al., 2014) provides a scripting interface in addition to the genome browser, to allow invoking R functions and displaying the results within the tool, however, this extension remains accessible only to users with relevant technical skills.

To lower this computational barrier, we had previously developed Spark (Nielsen et al., 2012) which employed an interactive visualization for pattern discovery, particularly in the early data exploration phases. However, support for cluster comparison and the ability to directly query for clusters with specific data patterns remain outstanding needs. In addition we realized that most biologists prefer a standard heat map visualization for communicating and publishing results.

Observing the limitations of available solutions, we designed and developed ChAsE in close collaboration with several groups of biologists and bioinformaticians with a focus on usability and interactivity. The main features include:

exploration through multiple linked interfaces including an interactive heat map and profile plot;

automatic clustering using k-means or manual clustering by sorting and selecting items in the heat map;

querying for absence or presence of signal in epigenomic marks;

comparing clusters by performing set operations;

exporting results for downstream analysis as well as producing high quality figures for publications. (examples included in the supplementary document).

2 Methods

2.1 Data input

The input dialog allows users to specify one or more marks as genome-wide read density data files (in Wig or bigWig formats) and a single region set containing genomic intervals of interest, such as regions around transcription start sites (in GFF or BED formats). Other parameters such as binning and normalization can be specified to allow for effective comparison of different marks on a uniform scale. The processing time depends on the size of the input and typically takes a few minutes per mark; however the processed data are stored so future loading will be only a few seconds per data.

2.2 Exploration

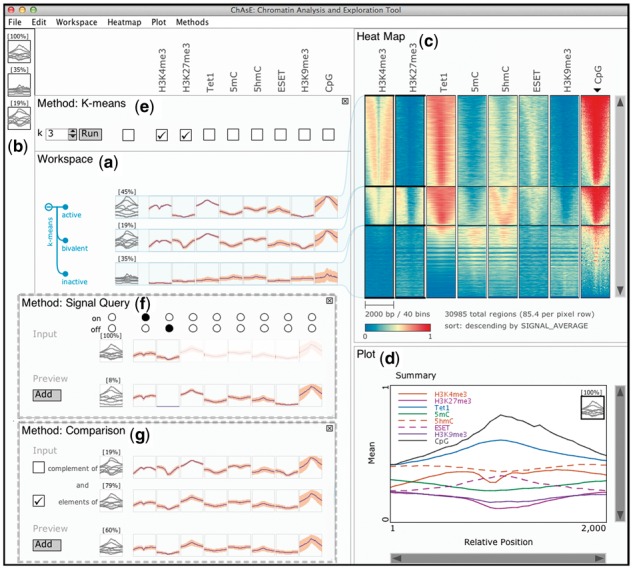

The graphical user interface consists of multiple linked panes. The ‘Workspace’ pane (Fig. 1(a)) shows a snapshot of the current analysis and is organized in a table layout where columns correspond to marks and rows correspond to subsets (clusters). Mark names are shown above the columns and clusters can have user specified labels. Each cell shows an average of the data for one mark in a subset as a profile plot, where the x-axis is relative position in the region and the y-axis is the signal value. For each subset, the left most column shows an overlay of the profile plots of all marks, as well as the size of the subset. Subsets can also be added to the ‘Favourites’ pane (Fig. 1(b)), and brought back to the workspace as needed.

Fig. 1.

ChAsE Interface: (a) Workspace Pane, (b) Favourites Pane, (c) Heat Map Pane, (d) Plot Pane, (e) Method Pane with K-means currently active, alternatively (f) Method Pane with Signal Query Method, (g) Method Pane with Comparison Method. The heat map is sorted by average CpG as indicated by the black inverted triangle

The ‘Heat map’ pane (Fig. 1(c)) displays a heat map view of the subsets. Each pixel row corresponds to one or more genomic regions and columns correspond to marks. The rows have a consistent order across the columns and can be sorted by several criteria such as signal average or user specified annotations. Users can interactively zoom and pan the heat map or drag over the heat map and create a subset of the selected regions.

The ‘Plot’ pane (Fig. 1(d)) shows a zoomed version of a single profile plot or the overlay plot where the profiles of all marks for a subset are displayed together. As the user moves the mouse over the plots, the corresponding mark is highlighted in the plot legend and across other panes.

Users can add custom labels to the subsets and export them as BED or GFF files (same format as the input regions file) for downstream analysis. In addition, the heat map or profile plots can be customized and exported to PDF format suitable for communication or publication of the findings.

2.3 Analysis

Methods are accessed from the menu and appear above the workspace pane (Fig. 1(e)). The ‘K-means’ method allows performing a clustering on the currently selected subset or the entire dataset. A user can indicate the number of clusters and toggle the check-boxes above the marks to specify which marks are included in the clustering. Clicking the ‘Run’ button executes the clustering and the results appear in the workspace in a tree structure. As the exploration continues, the user might be clustering subsets. To help him/her capture the exploration history, the clusters and subsequent cluster are organized in a hierarchical tree interface.

Subsets with child nodes are shown by a (-) sign when expanded or ⊕ sign when collapsed, and the leaf nodes are represented with solid circles. The user can further select a subset and perform clustering hierarchically.

The ‘Signal Query’ method shown in Figure 1(f) allows users to find regions with the signal present or absent in any combination of the marks. Once selected, the first row shows the input region sets with on/off switches allowing the user to specify either presence (on-selected), absence (off-selected) or no preference (neither selected). A region is considered having a signal if there is any enrichment of the corresponding mark within the bounds of the region. This would be most effective if the enrichment peaks have already been detected through a peak finding tool such as FindPeaks (Fejes et al., 2008). The second row shows a preview of the result for the currently selected combination and is dynamically updated as the user makes changes. Upon clicking the ‘Add’ button, the result is added to the Workspace.

The ‘Comparison’ method shown in Figure 1(g) allows the user to perform intersections across multiple subsets. The check box on the left of the summary plot for each subset allows the user to specify either inclusion (set intersection) or exclusion (set subtraction) of the set regions. Any subset currently present in the workspace may be used in the comparison method. For instance, the clusters might be from different runs of k-means on different marks or results of the signal query.

3 Application

We used ChAsE to study the relationships between DNA methylation, histone modifications and several DNA-binding regulatory proteins in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) (data available at the tool website). After loading the data, we performed a clustering across promoter regions using ChIP-seq data for H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, histone modifications characteristic of transcriptionally active and silent promoters, respectively. We specified these two marks for clustering by selecting the corresponding check boxes in k-means pane (Fig. 1(e)). The clustering results are shown in a tree in the workspace pane in Figure 1(a) with each cluster connected to the corresponding section in the heat map in Figure 1(c). The top cluster shows low H3K27me3 (blue) and moderate to high H3K4me3 (yellow-red) indicative of ‘active’ promoters. In contrast, the middle cluster has moderate H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 (blue-yellow) typical of transcriptionally poised or ‘bivalent’ promoters. The bottom cluster contains low levels of both modifications (blue) indicative of ‘inactive’ promoters. We used the contextual menu to appropriately label each of the clusters in the workspace pane.

We wanted to examine the DNA methylation status of these subpopulations, as well as to study the TET family of proteins known to catalyze the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxylmethylcytosine (5hmC). Consistent with recent reports (Yu et al., 2012), we observed high levels of 5hmC in the presence of TET1 at bivalent promoters in the middle cluster of Figure 1(c). Intriguingly, the top cluster of Figure 1(c) shows high levels of TET1, but only low to moderate levels of 5mC and 5hmC consistent with the model that H3K4me3-marked promoters harbor very low levels of DNA methylation. We also investigated the enrichment of the ESET histone methyltransferase at gene promoters. This protein catalyzes the methylation of H3K9 and deposition of H3K9me3 at retrotransposons and certain gene promoters (Karimi et al., 2011). Examining H3K9me3 and ESET ChIP-seq datasets revealed that ESET bound promoters in the top and middle clusters were almost all devoid of H3K9me3. This raised the possibility that ESET functions at promoters independent of its catalytic activity, perhaps to positively influence transcription. Furthermore, the presence of H3K4me3 at both the top and middle clusters may prevent the bound ESET from depositing H3K9me3 at such genomic sites. Although these observations have yet to be validated by further lab experiments, this example demonstrated the effectiveness of ChAsE for deriving new hypotheses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Rebecca Cullum, Olivia Alder, Bradford Hoffman and Arthur Kirkpatrick for their help evaluating this tool.

Funding

Funding for H.Y. was provided by NSERC PGS-D scholarship. C.B.N. was supported by CIHR and MSFHR post-doctoral fellowships. M.C.L. is supported by CIHR (20R91610). M.K. was supported by MSFHR post-doctoral fellowship. S.J.M.J. is a senior scholar of MSFHR. This work was partially funded by CIHR and Genome BC (EP2-120591).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Chelaru F. et al. (2014) Epiviz: interactive visual analytics for functional genomics data. Nat. Methods, 11, 938–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J., Kellis M. (2010) Discovery and characterization of chromatin states for systematic annotation of the human genome. Nat. Biotechnol., 28, 817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fejes A.P. et al. (2008) Findpeaks 3.1: a tool for identifying areas of enrichment from massively parallel short-read sequencing technology. Bioinformatics, 24, 1729–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon G. et al. (2008) ChromaSig: a probabilistic approach to finding common chromatin signatures in the human genome. PLoS Comput. Biol., 4, e1000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M.M. et al. (2011) DNA methylation and SETDB1/H3K9me3 regulate predominantly distinct sets of genes, retroelements, and chimeric transcripts in mESCs. Cell Stem Cell, 8, 676–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. et al. (2011) Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biol., 12, R83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C.B. et al. (2012) Spark: a navigational paradigm for genomic data exploration. Genome Res., 22, 2262–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M. et al. (2012) Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell, 149, 1368–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. et al. (2011) The human epigenome browser at Washington University. Nat. Methods, 8, 989–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.