Abstract

Motivation: Many problems of interest in dynamic modeling and control of biological systems can be posed as non-linear optimization problems subject to algebraic and dynamic constraints. In the context of modeling, this is the case of, e.g. parameter estimation, optimal experimental design and dynamic flux balance analysis. In the context of control, model-based metabolic engineering or drug dose optimization problems can be formulated as (multi-objective) optimal control problems. Finding a solution to those problems is a very challenging task which requires advanced numerical methods.

Results: This work presents the AMIGO2 toolbox: the first multiplatform software tool that automatizes the solution of all those problems, offering a suite of state-of-the-art (multi-objective) global optimizers and advanced simulation approaches.

Availability and Implementation: The toolbox and its documentation are available at: sites.google.com/site/amigo2toolbox.

Contact: ebalsa@iim.csic.es

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Optimization is at the core of many problems related to the modeling and design of biological systems (Banga, 2008). For example, model parametric identification involves two types of optimization problems (Balsa-Canto et al., 2010): parameter estimation, to compute unknown parameters by data fitting and optimal experimental design, to design the best experimental dynamic scheme for model identification.

The organization and behavior of biological systems can also be described based on optimality principles. This is the case in, e.g. (dynamic) flux balance analysis (Kauffman et al., 2003) or in the analysis of activation of metabolic pathways (Klipp et al., 2002). In this context, model-based dynamic optimization aims the computation of time-varying fluxes or enzyme concentrations and expression rates that minimize (or maximize) a given objective function (biomass production) or the best trade-off between various objectives (de Hijas-Liste et al., 2014).

Models can be used to confirm hypotheses, to draw predictions and to find those (time varying) stimulation conditions that result in a particular desired behavior via (multi-objective) optimal control. This is the case in, e.g. model-based metabolic engineering (Villaverde et al., 2016), pattern formation (Vilas et al., 2012) or drug dose optimization (Jayachandran et al., 2015).

All these problems can be stated as—or transformed to—(multi-objective) non-linear programming problems with algebraic and dynamic constraints. Their solution requires the combination of the control vector parameterization approach, a simulation method and a global optimizer.

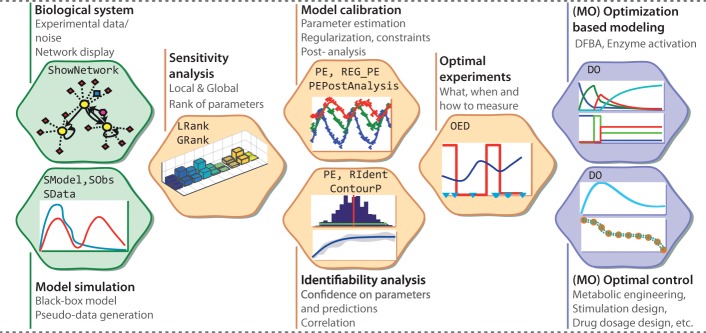

AMIGO2 is the first multi-platform (MATLAB-based) environment that automatizes the solution of all these problems (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). It fully covers the iterative identification of dynamic models, it allows using optimality principles for predicting biological behavior and it deals with the optimal control of biological systems using constrained multi-objective dynamic optimization.

Fig. 1.

AMIGO2 features and tasks (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

2 Summary of features

2.1 Models

The tool supports general non-linear deterministic dynamic models and black-box simulators, dealing with ordinary, partial or delay differential equations. Biological networks can be visualized linking to Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003).

2.2 Experimental scheme and data

Users can define multi-experiment schemes with maximum flexibility and several types of Gaussian experimental noise with known or unknown observable dependent variance.

2.3 Parameter estimation with regularization

It is possible to estimate parameters and initial conditions which may depend on the experiment using weighted least squares or log-likelihood functions. Ill-conditioned problems can be handled using Tikhonov regularization. Users may fix the regularization parameter or let the tool to automatically compute the most appropriate using the L-shaped Pareto curve (Gábor and Banga, 2015).

2.4 Identifiability and best fit post-analysis

The tool offers various methods to analyze model identifiability: (i) local and global parametric sensitivities; (ii) the Fisher Information Matrix for an asymptotic analysis; (iii) cost contour plots and (iv) a robust Monte-Carlo sampling approach. Results can be used to define and solve optimal experimental design problems aimed at improving identifiability. Besides, the validity of models along with the significance and determinability of their parameters are assessed using the χ2 goodness of fit and Pearsons χ2 tests, the autocorrelation of residuals, and the Akaike and Bayesian information criteria.

2.5 Optimal experimental design

To improve identifiability, users may automatically design simultaneous or sequential experiments optimizing observables, initial and stimulation conditions, number and location of sampling times and experiment durations. The tool allows for different design objectives and experimental error descriptions.

2.6 (Multi-objective) Optimal control

AMIGO2 solves optimal control problems with flexibility in the objective functional, stimuli interpolation, and path and point constraints. The aim is to find time varying stimulation conditions to maximize or minimize a given objective related to cell performance or to a desired behavior. The control vector parameterization method with mesh refining allow the efficient solution for smooth control profiles. Pareto fronts with best trade-offs for multi-objective cases can be obtained with the weighted sum method, the ϵ-constraint approach or the multi-objective genetic algorithm NSGA-II (Deb et al., 2002).

2.7 C based enhancements

The tool generates C code to offer the following modes of operation: (i) C based simulation, compatible with all tasks; (ii) C based cost function and (iii) stand-alone C code for parameter estimation.

2.8 Numerical methods

AMIGO2 incorporates the MATLAB-based initial value problem solvers as well as CVODES (Hindmarsh et al., 2005) to cover stiff, non-stiff and sparse dynamic systems. Parametric sensitivities can be computed by either direct methods or various finite differences schemes. Also, exact Jacobians can be obtained using symbolic manipulation. Regarding the optimizers, AMIGO2 interfaces to a suite of state-of-the-art solvers to cover constrained convex and non-convex, multi-objective non-linear optimization problems. Users can also test their optimizers within the toolbox.

2.9 Documentation

Descriptions of tool underlying theory, numerical methods, and usage are provided on the web page. Users can access HTML documentation from the MATLAB Help menu. Step by step examples illustrate the usage of the tool and serve as templates for new problems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the different beta-testers and M. Pérez-Rodríguez for the AMIGO2 logo design.

Funding

EU FP7 project NICHE [ITN grant number 289384], Spanish MINECO/FEDER projects IMPROWINE [grant number AGL2015-67504-C3-2-R] and SYNBIOFACTORY [DPI2014-55276-C5-2-R].

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Balsa-Canto E. et al. (2010) An iterative identification procedure for dynamic modeling of biochemical networks. BMC Syst. Biol., 4, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banga J. (2008) Optimization in computational systems biology. BMC Syst. Biol., 2, 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hijas-Liste G. et al. (2014) Global dynamic optimization approach to predict activation in metabolic pathways. BMC Syst. Biol., 8, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb K. et al. (2002) A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comp., 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar]

- Gábor A., Banga J.R. (2015) Robust and efficient parameter estimation in dynamic models of biological systems. BMC Syst. Biol., 9, 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarsh A.C. et al. (2005) Sundials: suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers. ACM Trans. Math. Softw., 31, 363–396. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran D. et al. (2015) Model-based individualized treatment of chemotherapeutics: Bayesian population modeling and dose optimization. PLoS One, 10, e013324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman K. et al. (2003) Advances in flux balance analysis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 14, 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klipp E. et al. (2002) Prediction of temporal gene expression. metabolic optimization by re-distribution of enzyme activities. Eur. J. Biochem., 269, 5406–5413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P. et al. (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res., 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilas C. et al. (2012) Dynamic optimization of distributed biological systems using robust and efficient numerical techniques. BMC Syst. Biol., 6, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde A. et al. (2016) Metabolic engineering with multi-objective optimization of kinetic models. J. Biotechnol., 222, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.