Abstract

Importance

Self-directed and interpersonal violence share some common risk factors such as a parental history of mental illness. However, relationships between the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease and these 2 related outcomes are unclear.

Objective

To examine associations between the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease and risks of attempted suicide and violent offending among offspring.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based cohort study of all persons born in Denmark 1967 through 1997, followed up from their 15th birthday until occurrence of adverse outcome or December 31, 2012, whichever came first.

Exposures

Array of parental psychiatric disorders and parental suicide attempt, delineated from records of secondary care treatments.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Using survival analyses techniques, incidence rate ratios were estimated for offspring suicide attempt and violent offending.

Results

We examined 1,743,525 cohort members (48.7 % female, total follow-up, 27.2 million person-years). Risks for offspring suicide attempt and violent offending were elevated across virtually the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease. Incidence rate ratios were the most elevated for parental diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder (suicide attempt, 3.96; 95% CI, 3.72-4.21; violent offending, 3.62; 95% CI, 3.41-3.84), and cannabis misuse (suicide attempt, 3.57; 95% CI, 3.25-3.92; violent offending, 4.05; 95% CI, 3.72-4.39), and for parental suicide attempt (suicide attempt, 3.42; 95% CI, 3.29-3.55; violent offending, 3.31; 95% CI, 3.19-3.44). Parental mood disorders (and bipolar disorder in particular) conferred more modest risk increases. A history of mental illness or suicide attempt in both parents was associated with double the risks compared with having just 1 affected parent. Associations between parental psychiatric disease and offspring violent offending were stronger for female than for male offspring, whereas little sex difference in risk was found for offspring suicide attempt.

Conclusions and Relevance

The similarities in risk patterns observed between the 2 outcomes may evidence a shared etiology. Early interventions to tackle parental mental disorders may be beneficial to both parents and children.

Introduction

Violence, both interpersonal and self-directed, presents a serious public health concern constituting a significant cause of premature death, disability and ill health.1,2 Studies from both psychiatric and forensic populations suggest that these 2 behaviors are associated, with elevated risks for aggression being found amongst those who engage in self-harm and vice versa.3,4 For example, elevated suicide risk was reported among violent offenders, particularly in those convicted for homicide or attempted homicide.5 The 2 behaviours are thought to share common determinants such as emotional dysregulation, lack of impulse control, poor problem-solving skills, substance use, and mental illnesses.3,4 It has been well-established that suicidal and violent behaviors aggregate within families, via possible interplay between genetics, epigenetics, and social and environmental influences.6–8 Elevated risks for the 2 behaviors in offspring have also been linked with a parental history of mental illnesses.9–13 However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease and both offspring suicide attempts and violent offending jointly in the same population. Previous studies examining broadly defined parental mental disorders (such as “personality disorders”) may also mask important heterogeneity according to diagnostic sub-categories.10–12 For example, borderline personality disorder is often linked with elevated risks for attempted suicide14,15 whereas interpersonal violence is closely related to antisocial personality disorder.16,17 However, it remains unclear how a parental diagnosis of these disorders is associated with risks of suicidal and violent behaviors in offspring, and how these risks compare between the 2 outcomes and in relation to other parental diagnoses.

For the study reported herein, we examined the associations between the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease and attempted suicide and violent offending among offspring. To enable like-for-like comparison, relative risks for both adverse outcomes were estimated in the same cohort at risk. The full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease investigated was delineated as follows:

-

(1)

Any mental disorders

-

(2)

Any organic mental disorders; specifically, dementia in Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia

-

(3)

Any substance use disorders; specifically, alcohol misuse, and cannabis misuse

-

(4)

Schizophrenia and related disorders (hereafter “broad schizophrenia”); specifically, schizophrenia (hereafter “narrow schizophrenia”), and schizoaffective disorder

-

(5)

Any mood disorders; specifically, bipolar disorder, recurrent depressive disorder, and single and recurrent depressive disorders

-

(6)

Any anxiety and somatoform disorders; specifically, obsessive compulsive disorder

-

(7)

Any personality disorders; specifically, borderline personality disorder, and antisocial personality disorder

-

(8)

Suicide attempt.

We also examined associations by offspring sex, and by exposure to psychiatric disease in the mother only, father only, and in both parents.

Methods

Study population

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Since 1968, all persons living in Denmark have been registered in the Danish Civil Registration System, which captures information such as date of birth, parents’ identities, and continuously updated information on vital status.18 The unique personal identification number enables accurate linkage across all national registers. The study cohort included all persons born in Denmark to Danish-born parents during 1967 through 1997 who resided in the country on their 15th birthday (N=1,743,525, 48.7% female). Because this project was based exclusively on registry data, according to the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data, Section 10, informed consent from persons in the study population was not required.

Parental mental disorders

Histories of mental illness for cohort members’ parents were obtained from the Psychiatric Central Research Register,19 which contains data on all admissions to psychiatric inpatient facilities from 1969 onwards. Information on all contacts with outpatient psychiatric departments and psychiatric emergency care was included from 1995 onwards. The International Classification of Diseases codes (Tenth Revision and Eighth Revision) used to delineate the parental mental disorders examined are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Onset of each parental mental disorder of interest was defined as the date of first contact (inpatient, outpatient, or psychiatric emergency care). Individuals with more than 1 disorder were included in the analysis for each specific disorder.

Parental and offspring suicide attempt

The classification of attempted suicide was identical to that applied previously20 using information from the Psychiatric Central Research Register19 and National Patient Register.21

Offspring violent offending

Data from the National Crime Register were available from 1980 onwards.22 We defined interpersonal violence as all convictions for homicide, assault, robbery, aggravated burglary or arson, possessing a weapon in a public place, violent threats, extortion, human trafficking, abduction, kidnapping, rioting or other public order offenses, terrorism, and all sexual offenses (except for possessing child pornographic material). We considered the first violent offense conviction after cohort members’ 15th birthdays because this is the age for adult criminal responsibility in Denmark.

Socioeconomic status

Parental socioeconomic status (SES), assessed in the year of cohort members’ 15th birthdays, was measured via paternal and maternal income, highest educational attainment, and employment status.23 To examine effects of interactions between parental SES and parental mental disorder, SES was stratified as lower, middle, and higher. These classifications were applied as described previously.24

Study design and statistical analyses

Cohort members were followed up from their 15th birthday until date of adverse outcome of interest, death, emigration from Denmark, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first. The 2 adverse outcomes were analysed separately. The cohort was followed up for a total of 27.2 million person-years. Persons with a first suicide attempt before follow-up at age 15 years were excluded from the suicide attempt analyses. Log-linear Poisson regression models, implemented in R, version 3.1.2, were fitted to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs). All models were adjusted for offspring age, sex, calendar year, and their interactions. In addition, the potential confounding and modifying effects of parental SES were also assessed. Offspring age, calendar year, and parental psychiatric history were treated as time-varying covariates; other covariates were time-fixed. Likelihood ratio-based 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each IRR estimate, and likelihood ratio interaction tests were used to assess effect modification by offspring sex and parental SES.

Results

A total of 44,472 cohort members (2.6% of the study population) first attempted suicide and 55,404 (3.2%) were convicted of a first violent offense during the study period, with the median age of onset for the two outcomes being 21.6 and 20.6 years, respectively. Males represented 46.7% of those who had attempted suicide and 90.0% of those with a violent offense conviction. Of the 91,800 persons who had at least 1 adverse outcome during the follow-up period, 39.6% attempted suicide only, 51.6% were only convicted of a first violent offense, and 8.8% had both outcomes. Table 1 gives the number of incident cases and incidence rates in relation to the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease, with at least 1 parent being affected. The highest incidence rates, for both adverse outcomes, were linked with parental cannabis misuse and attempted suicide.

Table 1. Number of incident cases and incidence rates per 100,000 person-years for suicide attempt and violent offending in relation to cohort members with at least 1 parent affected by a specific psychiatric diagnosis or a history of suicide attempt.

| Parental psychiatric diagnosis or suicide attempt | Offspring | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempted suicide | Violent offending | |||

| Incident cases, no. | Incidence rate per 100,000 person-years | Incident cases, no. | Incidence rate per 100,000 person-years | |

| Total | 44,472 | 162.5 | 55,404 | 203.5 |

| None | 31,460 | 133.0 | 41,011 | 174.4 |

| Any mental disorders | 12,286 | 341.0 | 13,451 | 375.9 |

| Organic mental disorders | 828 | 278.7 | 819 | 278.0 |

| Dementia in Alzheimer disease | 95 | 199.3 | 69 | 146.0 |

| Vascular dementia | 41 | 167.2 | 49 | 201.4 |

| Any substance use disorders | 5715 | 422.2 | 6644 | 496.7 |

| Alcohol misuse | 4887 | 413.6 | 5612 | 480.5 |

| Cannabis misuse | 439 | 718.0 | 564 | 937.5 |

| Broadly-defined schizophrenia a | 1660 | 326.6 | 1783 | 352.6 |

| Narrowly-defined schizophrenia b | 568 | 384.1 | 580 | 392.8 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 189 | 325.8 | 169 | 290.8 |

| Mood disorders | 4121 | 311.0 | 3961 | 299.4 |

| Bipolar disorder | 548 | 249.8 | 549 | 250.3 |

| Recurrent depressive disorder | 1322 | 306.7 | 1215 | 281.4 |

| Single and recurrent depressive disorders | 3532 | 309.0 | 3390 | 297.0 |

| Anxiety and somatoform disorders | 6628 | 404.0 | 7021 | 430.5 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 94 | 351.6 | 75 | 280.0 |

| Specific personality disorders | 4723 | 384.3 | 5138 | 421.0 |

| Borderline type personality disorder | 389 | 563.4 | 368 | 531.3 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 1027 | 574.4 | 1154 | 654.1 |

| Attempted suicide | 2841 | 737.0 | 3171 | 822.8 |

Schizophrenia and related disorders.

Schizophrenia only.

Incidence rate ratios for the 2 outcomes by types of parental disorder, adjusted for age, sex, and calendar year, are presented in Table 2. For each parental exposure examined, the reference group for IRR estimation was the group with neither parent affected by the particular disorder of interest. Risks for offspring suicide attempt and violent offending were elevated across the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease, except for Alzheimer disease, for which no significant link with offspring violent offending was found. For both offspring outcomes, the associations were particularly strong for parental antisocial personality disorder, cannabis misuse, and parental suicide attempt. Conversely, parental mood disorders, in particular bipolar disorder, conferred some of the lowest risk elevations, especially in relation to offspring violent offending.

Table 2. Suicide attempt and violent offending in offspring in relation to having at least 1 parent affected by a specific psychiatric diagnosis or a history of suicide attempt a.

| Parental psychiatric diagnosis or suicide attempt | IRR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Suicide attempt | Violent offending | |

| Any mental disorders | 2.53 (2.47-2.58) | 2.25 (2.21-2.30) |

| Organic mental disorders | 2.20 (2.05-2.35) | 1.91 (1.78-2.04) |

| Dementia in Alzheimer disease | 1.79 (1.45-2.17) | 1.18 (0.92-1.48) |

| Vascular dementia | 1.42 (1.03-1.91) | 1.70 (1.27-2.23) |

| Any substance use disorders | 2.93 (2.84-3.01) | 2.87 (2.80-2.94) |

| Alcohol misuse | 2.85 (2.76-2.93) | 2.76 (2.68-2.84) |

| Cannabis misuse | 3.57 (3.25-3.92) | 4.05 (3.72-4.39) |

| Broadly-defined schizophrenia b | 2.11 (2.01-2.22) | 1.86 (1.78-1.95) |

| Narrowly-defined schizophrenia c | 2.35 (2.16-2.55) | 2.01 (1.85-2.18) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 2.10 (1.81-2.41) | 1.55 (1.33-1.79) |

| Mood disorders | 2.04 (1.97-2.10) | 1.64 (1.59-1.70) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1.58 (1.45-1.72) | 1.35 (1.24-1.46) |

| Recurrent depressive disorder | 1.88 (1.78-1.99) | 1.53 (1.44-1.62) |

| Single and recurrent depressive disorders | 2.00 (1.93-2.07) | 1.62 (1.57-1.68) |

| Anxiety and somatoform disorders | 2.62 (2.56-2.69) | 2.34 (2.28-2.40) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 1.89 (1.53-2.30) | 1.32 (1.04-1.64) |

| Specific personality disorders | 2.62 (2.55-2.70) | 2.31 (2.25-2.38) |

| Borderline type personality disorder | 2.86 (2.59-3.16) | 2.36 (2.13-2.61) |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 3.96 (3.72-4.21) | 3.62 (3.41-3.84) |

| Attempted suicide | 3.42 (3.29-3.55) | 3.31 (3.19-3.44) |

Abbreviation: IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Adjusted for offspring sex and age, calendar year, and the interactions between these variables. Reference group: neither parent had the particular exposure of interest.

Schizophrenia and related disorders.

Schizophrenia only.

We next investigated separately: (1) those exposed to the parental disorder of interest only versus (2) those exposed to the disorder of interest in addition to other parental disorders. These results are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The reference group for IRR estimation was the group with neither a history of parental mental illnesses nor parental suicide attempt. Exposure to more than 1 parental disorders was common. Offspring of parents with cannabis misuse or antisocial personality disorder in addition to other disorders, or those with a parental history of both mental illness and suicide attempt, were at particularly high risks for both adverse outcomes. However, risks remained elevated for most of the parental diagnoses even when exposures to multiple parental disorders had been accounted for. Again, risks for both adverse outcomes were particularly high among those who were exposed only to parental antisocial personality disorder, or among those with a parental history of suicide attempt without mental disorder. Exposure to parental cannabis misuse only was also strongly linked with elevated risk for offspring violent offending. However, no significant associations between parental cannabis misuse and offspring suicide attempt were found after exposures to multiple disorders was accounted for.

Table 3. Offspring suicide attempt in relation to having at least 1 parent affected by a specific psychiatric diagnosis, by exposure to the specific diagnosis only or additionally to other diagnoses.

| Parental psychiatric diagnosis or suicide attempt | Exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | IRR (95% CI) a | |||

| Specific diagnosis only b | Specific diagnosis in addition to other parental disorders | Specific diagnosis only b | Specific diagnosis in addition to other parental disorders | |

| Any mental disorders | 10171c | 2115d | 2.36 (2.31-2.42)c | 4.41 (4.22-4.61)d |

| Organic mental disorders | 132 | 696 | 1.65 (1.39-1.95) | 3.02 (2.80-3.25) |

| Dementia in Alzheimer disease | 24 | 71 | 1.44 (0.94-2.10) | 2.72 (2.13-3.40) |

| Vascular dementia | 16 | 25 | 1.53 (0.90-2.41) | 2.01 (1.32-2.91) |

| Any substance use disorders | 1085 | 4630 | 2.53 (2.38-2.69) | 3.52 (3.41-3.63) |

| Alcohol misuse | 935 | 3952 | 2.45 (2.29-2.61) | 3.50 (3.38-3.62) |

| Cannabis misuse | 11 | 428 | 1.54 (0.80-2.64) | 4.59 (4.16-5.04) |

| Broadly-defined schizophrenia e | 263 | 1397 | 1.77 (1.57-2.00) | 2.76 (2.62-2.92) |

| Narrowly-defined schizophrenia f | 94 | 474 | 2.17 (1.76-2.64) | 3.06 (2.80-3.35) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 7 | 182 | 1.74 (0.75-3.36) | 2.62 (2.26-3.02) |

| Mood disorders | 858 | 3263 | 1.63 (1.52-1.74) | 2.71 (2.62-2.81) |

| Bipolar disorder | 52 | 496 | 1.19 (0.90-1.55) | 2.09 (1.91-2.28) |

| Recurrent depressive disorder | 0 | 1322 | … | 2.30 (2.18-2.43) |

| Single and recurrent depressive disorders | 525 | 3007 | 1.71 (1.56-1.86) | 2.53 (2.43-2.62) |

| Anxiety and somatoform disorders | 1700 | 4928 | 2.21 (2.10-2.32) | 3.28 (3.18-3.38) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 18 | 76 | 1.72 (1.04-2.64) | 2.56 (2.03-3.19) |

| Specific personality disorders | 579 | 4144 | 2.12 (1.95-2.29) | 3.18 (3.08-3.28) |

| Borderline type personality disorder | 27 | 362 | 2.36 (1.58-3.36) | 3.65 (3.28-4.04) |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 60 | 967 | 3.06 (2.35-3.90) | 4.90 (4.59-5.22) |

| Attempted suicide | 726g | 2115d | 3.12 (2.89-3.35)g | 4.41 (4.22-4.61)d |

Abbreviations: ellipses, not applicable; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

IRRs adjusted for offspring sex and age, calendar year, and the interactions between these variables. Reference group: neither parent has a mental illness diagnosis or a history of suicide attempt.

Not exposed to other parental mental disorders in the defined full spectrum except for the disorder of interest.

Offspring with suicide attempt with a history of any parental mental disorder but no history of parental suicide attempt.

Offspring with suicide attempt with a history of parental mental disorder and parental suicide attempt.

Schizophrenia and related disorders.

Schizophrenia only.

Offspring with suicide attempt with a history of parental suicide attempt but no history of parental mental disorder.

Table 4. Offspring violent offending in relation to having at least 1 parent affected by a specific psychiatric diagnosis, by exposure to the specific diagnosis only or additionally to other diagnoses.

| Parental psychiatric diagnosis or suicide attempt | Exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | IRR (95% CI) a | |||

| Specific diagnosis only b | Specific diagnosis in addition to other parental disorders | Specific diagnosis only b | Specific diagnosis in addition to other parental disorders | |

| Any mental disorders | 11222c | 2229d | 2.12 (2.07-2.16)c | 3.96 (3.79-4.13)d |

| Organic mental disorders | 127 | 692 | 1.45 (1.21-1.71) | 2.48 (2.30-2.67) |

| Dementia in Alzheimer disease | 15 | 54 | 0.86 (0.50-1.37) | 1.69 (1.28-2.19) |

| Vascular dementia | 13 | 36 | 1.23 (0.67-2.02) | 2.72 (1.93-3.71) |

| Any substance use disorders | 1356 | 5288 | 2.60 (2.46-2.74) | 3.28 (3.19-3.37) |

| Alcohol misuse | 1148 | 4464 | 2.47 (2.33-2.62) | 3.23 (3.13-3.33) |

| Cannabis misuse | 33 | 531 | 4.14 (2.88-5.71) | 4.82 (4.42-5.24) |

| Broadly-defined schizophrenia e | 295 | 1488 | 1.52 (1.36-1.70) | 2.36 (2.24-2.48) |

| Narrowly-defined schizophrenia f | 92 | 488 | 1.67 (1.35-2.03) | 2.57 (2.35-2.81) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 5 | 164 | 0.86 (0.31-1.85) | 1.89 (1.62-2.20) |

| Mood disorders | 776 | 3185 | 1.20 (1.12-1.29) | 2.20 (2.12-2.28) |

| Bipolar disorder | 48 | 501 | 0.89 (0.66-1.17) | 1.73 (1.58-1.88) |

| Recurrent depressive disorder | 0 | 1215 | … | 1.81 (1.71-1.91) |

| Single and recurrent depressive disorders | 485 | 2905 | 1.26 (1.15-1.38) | 2.04 (1.97-2.12) |

| Anxiety and somatoform disorders | 1870 | 5151 | 2.00 (1.91-2.10) | 2.84 (2.76-2.93) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 13 | 62 | 1.01 (0.56-1.67) | 1.78 (1.37-2.26) |

| Specific personality disorders | 745 | 4393 | 2.08 (1.94-2.24) | 2.68 (2.60-2.77) |

| Borderline type personality disorder | 22 | 346 | 1.43 (0.91-2.12) | 2.98 (2.68-3.31) |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 88 | 1066 | 3.47 (2.80-4.25) | 4.24 (3.99-4.51) |

| Attempted suicide | 942g | 2229d | 3.35 (3.13-3.57)g | 3.96 (3.79-4.13)d |

Abbreviations: ellipses, not applicable; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

IRRs adjusted for offspring sex and age, calendar year, and the interactions between these variables. Reference group: neither parent has a mental illness diagnosis or a history of suicide attempt.

Not exposed to other parental mental disorders in the defined full spectrum except for the disorder of interest.

Offspring with violent offending with a history of any parental mental disorder but no history of parental suicide attempt.

Offspring with violent offending with a history of parental mental disorder and parental suicide attempt.

Schizophrenia and related disorders.

Schizophrenia only.

Offspring with violent offending with a history of parental suicide attempt but no history of parental mental disorder.

Results adjusted for parental SES are given in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Comparison with Table 1 shows that between 20% and 50% of the elevated risks for offspring suicide attempt and violent offending were accounted for by those confounding influences. However, even after making this additional adjustment, risk of violent offending was still particularly elevated among those with a parental history of suicide attempt, or with a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or cannabis misuse, while attempted suicide risk remained raised particularly for those exposed to parental suicide attempt or antisocial personality disorder. There were also significant interactions between parental mental disorder and parental SES for the risk of both adverse outcomes (χ2[22] = 120.8, P <.001 for suicide attempt; χ2[22] = 170.4, P <.001 for violent offending). Further details can be found in eResults 1 and eTable 3 in the Supplement.

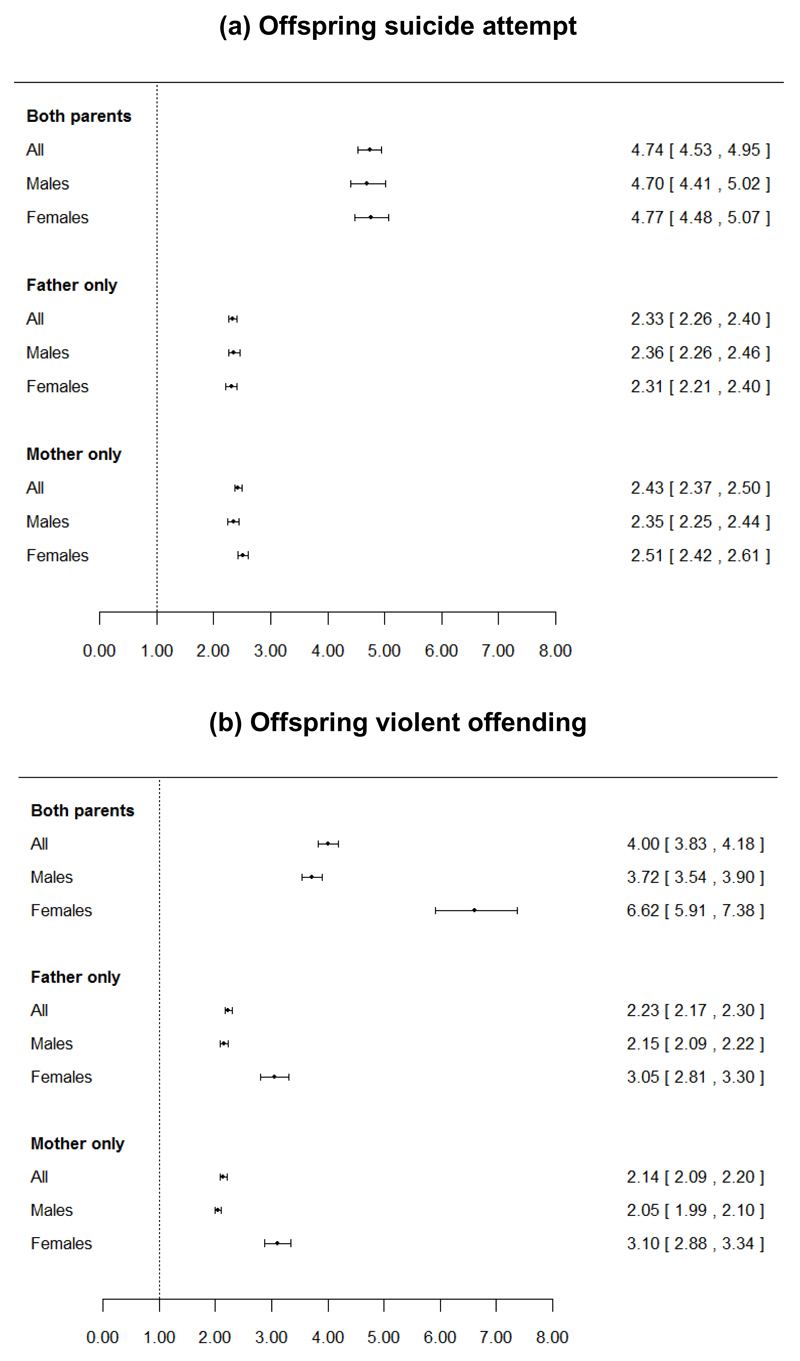

The Figure shows the IRRs for the 2 offspring outcomes in relation to whether the mother only, father only, or both parents had a history of any psychiatric diagnosis or suicide attempt, stratified by offspring sex. Compared with having only 1 affected parent, a history of psychiatric disease in both parents was associated with doubled risks of both adverse outcomes in offspring. The associations between parental psychiatric disease and offspring violent offending were stronger for female than for male offspring (P <.001), particularly when both parents were affected. Conversely, there was little heterogeneity in IRR estimates for attempted suicide by offspring sex. Further discussion of these results is reported in eResults 2 in the Supplement.

Figure. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs for offspring suicide attempt and offspring violent offending, according to whether the mother only, the father only or both parents were affected by any psychiatric disorder, stratified by offspring sex.

The reference group was individuals with neither parent having a psychiatric diagnosis or history of suicide attempt. Models adjusted for offspring sex and age, calendar year, and the interactions between these variables. Symbols indicate IRR, and error bars, 95% CI.

Results from further investigation of offspring sex-specific associations with the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease, with at least 1 parent being affected, are given in eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement. The sex-specific IRRs for suicide attempt were generally of comparable magnitude, whereas IRRs for violent offending were greater for female than for male offspring for most types of parental psychiatric disease.

Discussion

Main findings

Elevated risks for offspring attempted suicide and violent offending were evident across a broad spectrum of parental psychiatric disease. Risks were particularly elevated for parental diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder, cannabis misuse, and prior suicide attempt, whereas lower elevations in risk were seen in relation to parental mood disorders - bipolar disorder in particular. The similarities in relative risk patterns observed for both adverse outcomes indicate that self-directed and interpersonal violence may have a shared etiology. A history of mental illnesses or suicide attempt in both parents was associated with doubled risks versus having only 1 affected parent. Associations between parental psychiatric disease and offspring violent offending were stronger for female than for male offspring, whereas the sex-specific IRRs for offspring suicide attempt were generally comparable.

Existing evidence and interpretations

This is the first study to investigate the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease and offspring suicide attempt and violent offending in the same population. Our findings for suicide attempt align with those from a Swedish national registry study, which found that risks were particularly elevated for offspring exposed to parental personality disorders, suicide attempt, and substance misuse.10 Similarly, the World Mental Health surveys revealed that elevated risk of offspring suicide attempt was linked with parental depression, panic or generalized anxiety disorder, substance misuse, and suicidal behavior.9 However, neither parental personality disorders nor sub-categories within substance use were investigated.9 Specific types of personality disorders were also not examined in the Swedish study.10

Strong associations between parental personality disorders and substance misuse and offspring violent offending have previously been reported from a Danish national registry study.11 By examining sub-categories within these disorders, we additionally revealed that offspring violent offending risks were especially elevated in relation to parental cannabis misuse and antisocial personality disorder, even after adjustment for other parental disorders. Among persons with a personality disorder diagnosis, attempted suicide is particularly strongly linked with borderline personality disorder 14,15 whereas interpersonal violence is closely related to antisocial personality disorder.16,17 By investigating these 2 adverse behaviors in the same population, we found that risks for both were more strongly associated with parental antisocial personality disorder than with parental borderline personality disorder.

Shared genetic vulnerability to psychiatric disease may be 1 possible pathway that could explain our findings,25 although the intergenerational transmission of suicidal risks has been reported to be independent of familial transmission of mental disorders.6,9,10,26 In the full spectrum of disorders examined here, the strongest associations with offspring suicide attempt and violent offending were found with parental antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, and suicide attempt. These associations remained relatively strong even after adjustment for parental SES or other parental disorders, except for the link between parental cannabis misuse and offspring suicide attempt, which was no longer significant after the effects of other parental disorders were accounted for. Substance misuse and antisocial personality disorder, as well as suicidal behavior and violence perpetration, are often characterised by behavioral dysregulation and impulsive-aggressive traits,4,17 which may also contribute to elevated risks of deaths from accidents and other causes amongst those with a history of self-harm.27 Evidence has supported the heritability of these traits, which have also been identified as possible intermediate phenotypes for suicidal behavior.28–30 The intergenerational transmission of such traits may thus contribute to the particularly high risks for suicidal behavior and violent offending among those with a parental history of antisocial personality disorder, substance misuse and suicide attempt. In addition, higher levels of impulsivity and aggression in offspring and their parents were more strongly linked with younger than with older age suicidal behaviors.31–33 The early median ages of onset of offspring adverse outcomes in our cohort may thus lend further support to the familial transmission of these traits.

Children of parents with a history of psychiatric disease are at increased risk of being additionally exposed to other adversities such as maladaptive parenting practice, family violence, abuse, neglect, and financial hardship, and the impact of these harmful environmental factors on offspring risks of suicidal behavior and violence perpetration is thought to be cumulative.34–37 However, even after SES adjustment, many of the links between parental psychiatric disease and offspring suicide attempt and violent offending in our study remained significantly elevated. Exposure to adversities during childhood and sensitive developmental periods may also lead to alteration of gene expression via epigenetic processes, resulting in altered neurobiological function such as stress-responsive systems, increasing vulnerability for adverse outcomes such as suicidal and aggressive behaviors in later life.29,38

Our study revealed that having 2 parents affected by psychiatric disease doubled the risks for both adverse outcomes versus cohort members with only 1 affected parent. Evidence for assortative mating has been reported in psychiatric populations.39 The doubling of risks observed could be attributed not only to the inheritance of disorders or traits from both parents but also to disturbed family environments exacerbated by having 2 parents affected by mental illnesses. Our study has also shown that, for most of the parental disorders examined, associations between parental psychiatric disease and offspring violent offending were stronger for female than for male offspring. Because females perpetrate violent crimes less frequently than males and aggressive behavior in women is viewed as being less culturally acceptable than in men, it has been suggested that a higher “risk threshold” for violent criminality exists for women than for men.40,41 Research on adolescence has also indicated that the cumulative effects of risk factors for delinquency are stronger among girls than for boys.40 These aspects may explain the larger female than male relative risks for violent offending observed in this study, but further research is needed to explore why for certain parental diagnoses, for example, bipolar disorder (eTable 5 in the Supplement), there was no evidence of greater relative risk for violent offending in male versus female offspring.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of our study include examination of a complete national cohort, providing abundant statistical power to examine rare exposures and outcomes. Because all exposures and outcomes were collected prospectively, recall bias was eliminated, an issue that would be pertinent to retrospective self-reporting of parental psychiatric disease by offspring. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register also enabled us to investigate the full spectrum of parental mental disorders, including more narrowly defined categories. In examining the same cohort, we were also able to compare risks for the 2 outcomes without differential intercohort biases. The most important limitation of our study was that, although we controlled for parental SES, we were not able to adjust for other potential confounders such as parental criminal histories7 or cohort members’ experiences of abuse. Data on criminal offending were only available from 1981 onward, and childhood abuse episodes are not routinely recorded in the registers. In addition, milder cases of mental disorders, self-harm, and substance misuse treated in primary care only are not recorded in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Hence, our cases of suicide attempt and parental mental disorders only included those with a severity that resulted in secondary care treatment.

Conclusions

Elevated risks of both attempted suicide and violent offending in offspring are evident across a broad spectrum of parental psychiatric disease, with the links being strongest in relation to parental antisocial personality disorder, cannabis misuse and attempted suicide. Children with 2 affected parents are particularly vulnerable. Psychiatrists and other professionals treating adults with mental disorders and suicidal behavior should consider also evaluating the mental health and psychosocial needs of their patients’ children. Early interventions could benefit not only the parents but also their offspring. In particular, interventions that aim to reduce the incidence of and ameliorate the effects of parental substance misuse may help to reduce their offspring’s future risks for suicidality and violence.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question: How are risks of attempted suicide and violent offending in offspring related to the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease?

Findings: In this population-based cohort study of 1,743,525 persons, risks for offspring suicide attempt and violent offending were significantly elevated across virtually the full spectrum of parental psychiatric disease. For both adverse outcomes in offspring, the greatest elevations in risk were linked with parental diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder, cannabis misuse, and prior suicide attempt.

Meaning: The similarities in relative risk patterns observed may evidence a shared etiology between self-directed and interpersonal violent behaviors.

Acknowledgment

Funding/Support

This study was supported by a European Research Council Starting Grant (335905) awarded to Dr Webb.

Role of Funder

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None reported.

Access to Data and Data Analysis

Dr Mok (University of Manchester) has full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Pearl L.H. Mok, Centre for Mental Health and Safety, University of Manchester, Manchester, England.

Carsten Bøcker Pedersen, Centre for Integrated Register-based Research, CIRRAU, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; National Centre for Register-Based Research, Business and Social Sciences, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; The Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH, Aarhus, Denmark.

David Springate, Institute of Population Health, University of Manchester, Manchester, England.

Aske Astrup, Centre for Integrated Register-based Research, CIRRAU, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; National Centre for Register-Based Research, Business and Social Sciences, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Nav Kapur, Centre for Mental Health and Safety, University of Manchester, Manchester, England.

Sussie Antonsen, Centre for Integrated Register-based Research, CIRRAU, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; National Centre for Register-Based Research, Business and Social Sciences, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Ole Mors, The Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH, Aarhus, Denmark; Psychosis Research Unit, Aarhus University Hospital, Risskov, Denmark.

Roger T. Webb, Centre for Mental Health and Safety, University of Manchester, Manchester, England.

References

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Injuries and violence: the facts 2014. Geneva: WHO Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubell KM, Vetter JB. Suicide and youth violence prevention: The promise of an integrated approach. Aggress Violent Behav. 2006;11(2):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Donnell O, House A, Waterman M. The co-occurrence of aggression and self-harm: Systematic literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:325–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb RT, Shaw J, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Appleby L, Qin P. Suicide risk among violent and sexual criminal offenders. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(17):3405–3424. doi: 10.1177/0886260512445387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brent DA, Mann JJ. Family genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;133C(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Långström N. Violent crime runs in families: a total population study of 12.5 million individuals. Psychol Med. 2011;41(1):97–105. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tidemalm D, Runeson B, Waern M, et al. Familial clustering of suicide risk: a total population study of 11.4 million individuals. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2527–2534. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gureje O, Oladeji B, Hwang I, et al. Parental psychopathology and the risk of suicidal behavior in their offspring: results from the World Mental Health surveys. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1221–1233. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Rasmussen F, Wasserman D. Familial clustering of suicidal behaviour and psychopathology in young suicide attempters. A register-based nested case control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(1):28–36. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean K, Mortensen PB, Stevens H, Murray RM, Walsh E, Agerbo E. Criminal conviction among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Psychol Med. 2012;42(3):571–581. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilcox HC, Kuramoto SJ, Lichtenstein P, Långström N, Brent DA, Runeson B. Psychiatric morbidity, violent crime, and suicide among children and adolescents exposed to parental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):514–523. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borges G, Borges R, Medina Mora ME, Benjet C, Nock MK. Parental psychopathology and offspring suicidality in Mexico. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(2):123–135. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.776449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, Hale N. Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: Prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. J Pers Disord. 2004;18(3):226–239. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.3.226.35445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuels J. Personality disorders: Epidemiology and public health issues. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23(3):223–233. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coid J, Yang M, Roberts A, et al. Violence and psychiatric morbidity in a national household population - a report from the British Household Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(12):1199–1208. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountoulakis KN, Leucht S, Kaprinis GS. Personality disorders and violence. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(1):84–92. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f31137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1058–1064. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen MF, Greve V, Høyer G, Spencer M. The Principal Danish Criminal Acts. 3rd Edition. Copenhagen: DJØF Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danmarks Statistik. IDA - en Integret Database for Arbejdsmarkedsforskning. Copehagen: Danmarks Statistiks Trykkeri; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webb RT, Antonsen S, Mok PLH, Agerbo E, Pedersen CB. National cohort study of suicidality and violent criminality among Danish immigrants. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 29;10(6):e0131915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean K, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Murray RM, Walsh E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric outcomes among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(8):822–829. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geulayov G, Gunnell D, Holmen TL, Metcalfe C. The association of parental fatal and non-fatal suicidal behaviour with offspring suicidal behaviour and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(8):1567–1580. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawton K, Harriss L, Zahl D. Deaths from all causes in a long-term follow-up study of 11,583 deliberate self-harm patients. Psychol Med. 2006;36(3):397–405. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coccaro EF, Bergeman CS, Kavoussi RJ, Seroczynski AD. Heritability of aggression and irritability: a twin study of the Buss-Durkee aggression scales in adult male subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(3):273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann JJ, Arango VA, Avenevoli S, et al. Candidate endophenotypes for genetic studies of suicidal behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seroczynski AD, Bergeman CS, Coccaro EF. Etiology of the impulsivity/aggression relationship: genes or environment? Psychiatry Res. 1999;86(1):41–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGirr A, Turecki G. The relationship of impulsive aggressiveness to suicidality and other depression-linked behaviors. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):460–466. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGirr A, Renaud J, Bureau A, Seguin M, Lesage A, Turecki G. Impulsive-aggressive behaviours and completed suicide across the life cycle: a predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychol Med. 2008;38(3):407–417. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, et al. Peripubertal suicide attempts in offspring of suicide attempters with siblings concordant for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1486–1493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barker ED, Copeland W, Maughan B, Jaffee SR, Uher R. Relative impact of maternal depression and associated risk factors on offspring psychopathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(2):124–129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook JS. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):741–749. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin KA, Greif Green J, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1151–1160. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301(21):2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordsletten AE, Larsson H, Crowley JJ, Almqvist C, Lichtenstein P, Mataix-Cols D. Patterns of nonrandom mating within and across 11 major psychiatric disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):354–361. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong TM, Loeber R, Slotboom AM, et al. Sex and age differences in the risk threshold for delinquency. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(4):641–652. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9695-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang M, Coid J. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity and violent behaviour among a household population in Great Britain. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(8):599–605. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.