Abstract

The development of indefinitely propagating human ‘mini-guts’ has led to a rapid advance in gastrointestinal research related to transport physiology, developmental biology, pharmacology, and pathophysiology. These mini-guts, also called enteroids or colonoids, are derived from LGR5+ intestinal stem cells isolated from the small intestine or colon. Addition of WNT3A and other growth factors promotes stemness and results in viable, physiologically functional human intestinal or colonic cultures that develop a crypt–villus axis and can be differentiated into all intestinal epithelial cell types. The success of research using human enteroids has highlighted the limitations of using animals or in vitro, cancer-derived cell lines to model transport physiology and pathophysiology. For example, curative or preventive therapies for acute enteric infections have been limited, mostly due to the lack of a physiological human intestinal model. However, the human enteroid model enables specific functional studies of secretion and absorption in each intestinal segment as well as observations of the earliest molecular events that occur during enteric infections. This Review describes studies characterizing these human mini-guts as a physiological model to investigate intestinal transport and host pathogen interactions.

The gastrointestinal tract is a centre of absorption and secretion, with the capacity to sustain microbial and viral pathogen assault as well as regenerate following damage by infections or radiation1,2. The complex morphology of the intestine includes the crypts of Lieberkuhn as well as the villus and surface enterocytes, and has been well described3–5. The use of in vitro intestinal models, such as T84 or Caco-2 cells, has led to breakthroughs in understanding of functional intestinal physiology and cancer biology, but has also shown disparate results from rodent models6. The three segments of the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum) and the proximal and distal colon have been shown to have segment-specificity in transport, protein expression and pathogen-induced disease7–9. Discoveries have also come from the use of ex vivo, self-assembling ‘mini-guts’, termed organoids (derived from iPS (induced pluripotent stem) cells)10, enteroids and colonoids (derived from adult stem cells from the small intestine and colon, respectively)11. Although these mini-guts have been studied in detail for intestinal development and stem cell lineage, fewer studies have investigated their use as functional physiology and pathophysiology models.

The most common manifestation of acute enteric infections is pathogen-induced diarrhoea. Although the use of oral rehydration solution has saved many lives, no effective antidiarrhoeal drug exists12,13. Antibiotic use against enteric infections has proven, at best, to be useless, or at worst, to enhance virulence, making the pathogen more harmful to the host. Diarrhoea occurs due to the imbalance between electrolyte absorption and secretion, resulting in a substantial increase in water secretion13. To develop effective antidiarrhoeal drugs or a general antisecretory agent, the physiology of intestinal absorption and secretion and the pathophysiological changes from specific enteric pathogens and their virulent factors or toxins must first be characterized. This Review highlights the uses of enteroids, colonoids and organoids in functional transport physiology studies and host–pathogen studies.

Limitations of traditional intestinal models

Nutrient absorption is one of the main functions of the intestine. T84, Caco-2, and HT29 cells are the in vitro cell lines commonly used to study small intestinal and colonic absorption, regulation of intestinal transport in health and disease, and the effects of enteric pathogens on the host intestinal epithelia, including pathogen colonization14–16. Notably, these cell lines are immortalized cancer-derived cells, and might not accurately represent the normal, healthy human intestine. Although these lines have been used to model the human intestine owing to their ability to replicate intestinal permeability and membrane transport, studies have shown that subclones of these cell lines, in particular Caco-2, have disparate protein expression and mislocalization from laboratory to laboratory, and also show differing protein expression compared to the human intestine17,18. Additionally, these commonly used in vitro cell lines lack intestinal segment specificity and also consist of a single cell type, a misleading representation of the complex multicellular identity of the intestine. Thus, some studies in both intestinal physiology and pathophysiology have been misleading. A prime example is passive and carrier-mediated drug absorption in the intestine18,19. Comparisons between human intestinal samples and Caco-2 cells showed that passive drug absorption was similar, resulting in the use of Caco-2 cells as a model for drug absorption in the intestine during drug discovery14,20. However, the rate of active drug absorption in Caco-2 cells does not necessarily correlate to the rate of active drug absorption in humans. In some cases, drugs are poorly or not absorbed in Caco-2 cells but are absorbed in the human intestine18,19. These findings might be explained in part by the reduced expression of several transporters in Caco-2 cells compared with the human intestine18. Furthermore, Caco-2 cells begin to differ in functional and transport characteristics as their passage number increases, or as they age21. Disparate findings between the immortalized cell lines and rodent intestine have added to the confusion. For example, the functional role of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase II (cGKII) in ion transport was contradictory between T84 cells (no cGKII involvement)22 and mouse intestine (cGKII is involved in fluid homeostasis)23. Another marked difference has been reported for the bile salt transporter ASBT between Caco-2 cells and mouse intestine24. Although not fully understood, ASBT might be regulated by differing mechanisms or differing P-type ATPases in Caco-2 cells and mouse intestine. These examples highlight the need for a physiological model that is more representative of the normal human intestine.

Key points.

Human ‘mini-guts’ generated from crypt-based or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells functionally recapitulate normal intestinal transport physiology and model pathophysiologic changes following interactions with enteric pathogens

iPS-cell-derived intestinal organoids can be used to model intestinal development and engrafted in vivo to differentiate the epithelium along a crypt–villus axis supported by subepithelial and smooth muscle layers

3D enteroids and colonoids derived from intestinal stem cells can be used to measure ion, nutrient and water absorption or secretion as part of normal intestinal transport function

Both human intestinal organoids and enteroids or colonoids can be used as models to study enteric bacterial and viral pathogenesis

Enteroids and colonoids can be grown on 2D permeable supports to enable apical access to study host pathogen interactions as well as drug absorption and/or metabolism

Stem cell or iPS-cell-derived gastrointestinal organoids from the stomach, pancreas and liver are also being developed as models to study development, infection and regenerative medicine

Most of the intestinal in vitro cell lines represent enterocytes, and therefore do not produce the thick outer mucus layer (primarily composed of MUC2) that serves as the first point of contact between enteric pathogens and the host intestine25. As studies have shown, the outer mucus layer provides a defence mechanism as well as a nutrient source for both pathogens and gut microbiota9,26,27. These findings emphasize that the commonly used in vitro lines have limited value for host–pathogen studies. Thus, a better system to model the human intestine is needed.

Human ex vivo models

Organoids

The two cell sources used for the formation of organoids are human iPS cells or, less often, embryonic stem cells. These cell sources are differentiated into 3D human intestinal organoids (HIOs)10,28. HIOs are useful for understanding the developmental biology of the intestine as they initially represent a fetal-like intestine that does not mimic intestinal segment specificity29. However, HIOs have been shown to form large pieces of intestine with villi-like structures when transplanted under the kidney capsule of a mouse30. This HIO-derived intestine can be removed and used for crypt isolation and enteroid formation.

The conversion of iPS cells into in vitro HIOs was pioneered by Wells and colleagues. Their work elegantly describes how initial conversion into HIOs involves sequential manipulation of signalling pathways that mimic in vivo intestinal development10,31. Activin A, a mimic of Nodal and member of the TGFβ family, initiates expression of the transcription factors Sox-17 and HNF-3-beta (FOXA2), leading to posterior endoderm patterning during morphogenesis of the definitive endoderm into a primitive gut along an anterior–posterior axis. This posterior patterning eventually gives rise to the small intestine. Expression of WNT3A and FGF-4 act synergistically to differentiate the endoderm into CDX-2-expressing intestine, forming gut tubes and 3D spheroids. Exposure to growth factors including epidermal growth factor (EGF), Noggin, and R-spondin-1 results in spheroid enlargement and differentiation into the HIOs10. These HIOs are comprised of intestinal epithelial cell types, such as crypt-residing stem cells, Paneth cells, epithelial transporting cells, goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells and the mesenchyme that surrounds the epithelium. The mesenchyme consists of myofibroblasts, circular and longitudinal smooth muscle, and endothelial cells. Smooth muscle contraction leads to pseudo-villus formation and separation of the crypt-residing cells from the surface villus-residing cells30. However, as in enteroids, the HIOs lack a vascular plexus, M cells, Peyer’s patches, mesenteric lymph nodes and enteric nerves.

Although HIOs are polarized (with a luminally facing brush border) and can perform some transport functions, such as dipeptide absorption, they are fetal in nature and do not reproduce segment specificity by expressing proteins specific for the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or colon28. Rather, HIOs form a mixed population of proximal intestinal cells (expressing GATA-4 and GATA-6) and distal intestinal cells (expressing GATA-6, but not GATA-4). However, attempts are ongoing to use HIOs to produce mature intestine with segment specificity. The most developed method provides HIOs with a highly vascular environment by implantation beneath the kidney capsule of mice or enclosure in the omentum30. This approach has led to a marked increase in the size of the implanted HIOs, with distinct crypt and mature villus compartments, as well as conversion from fetal to more mature adult-like small intestinal characteristics. However, this method does not cause segmental differentiation of the HIOs into specific parts of the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum)30. Other changes include development of brush border enzymes involved in digestion, production of defensins and expression of the stem cell marker OLFM4 in the crypts29. After removal from beneath the kidney capsule, the mature HIOs express the intestinal cell lineages seen in mature small intestine. The enterocytes have a mature brush border and tight junctions and show increased expression of brush border proteins (such as sucrase isomaltase, dipeptidyl peptidase IV, trehalase, maltase, and lactase)30. Other cell lineages distribute along the crypt–villus axis similarly to the normal intestine, including the crypt-residing Paneth cells and the proliferative stem cells at the crypt base. Given that the implanted HIOs grow exponentially in size, they have been excised and used to generate enteroids, which can be propagated and differentiated as ex vivo cultures32.

The advantages of using HIOs over enteroids and colonoids include the ability to study various stages of development and lumen formation31,32, the inclusion of myofibroblasts to create a more complex stem cell niche than that which exists in enteroids and colonoids and the additional Wnt source from the mesenchyme (which is also probably more similar to normal intestinal homeostasis). The disadvantages include the length of time and effort needed to create a single HIO line (~35 days to 3 months), the fetal nature of the epithelium and the lack of segment specificity (BOX 1).

Box 1. Key features of organoids.

Advantages

Models all intestinal cell types, not only epithelia-derived, including fibroblasts, smooth muscle, mesenchyme and endothelial cells

Able to model into proximal and distal small intestine

Protein expression is stable over time

Potential to make into enteroids

Can use for high-throughput studies

Can use for developmental studies

Represents fetal intestine

Disadvantages

Generic intestine, unable to fully differentiate into all intestinal segments

Represents fetal intestine

Villus can be formed but with extreme effort

Lacks peristalsis and luminal and blood flow

Enteroids and colonoids

Human enteroids (small intestine) and colonoids (large intestine) are ex vivo primary intestinal cultures derived from the crypts of paediatric or adult intestine11. The intestinal tissue source is generally biopsy samples obtained endoscopically or from surgical resections. Although the nomenclature of these cultures has been inconsistent, this Review refers to the nomenclature of tissue-derived mini-intestines as enteroids or colonoids, as described by the NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Intestinal Stem Cell Consortium33. The successful development and propagation of human enteroids and colonoids is dependent on numerous growth factors that mimic those secreted by the mesenchyme and create an ideal intestinal stem cell niche for the LGR5+ intestinal stem cells34,35. These growth factors have been described extensively in previous reviews36–39. The most critical growth factor is WNT3A. Although Paneth cells are required for the intestinal stem cell niche and are thought to produce WNT3A35, it is in too low abundance to support the stem cell niche needed to continuously grow human enteroids and can be compensated by exogenous WNT3A in the media.

Using the growth factors first described by Sato et al.11,40, enteroids and/or colonoids can be produced from each segment of the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum), colon (proximal, transverse, distal), and recto-sigmoid. These cultures grown ex vivo have been maintained in various laboratories for >2 years with no detectable changes in chromosomal number or other cancerous characteristics of wild-type cultures41. As documented for the small intestinal enteroids, they maintain protein expression characteristic of the specific intestinal segment (including specific transcription factors that define the segments) or suppress protein expression normally not found in that specific segment8. Initial growth of enteroids is polarized (as with the normal intestine), forming spheroids with the apical surface facing inwards and apical microvilli and basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase, Cadherin-1 (E-cadherin), and Catenin beta-1 (beta-catenin) expression. However, these enteroids express a protein profile that is more similar to that expressed by the crypt8. Thus, they are considered ‘not differentiated’ and remain in a highly proliferative state in culture (FIG. 1a). Withdrawal of WNT3A induces a loss of proliferation (FIG. 1a) and a distinct pattern of differentiation in all cells42 (BOX 2) that includes: one, expansion of cells present from only the crypt base stem cells, Paneth cells, goblet cells and transit-amplifying cells to an increased number of goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells and M cells or tuft cells, with the last two (M cells and tuft cells) dependent on manipulation of various growth factors43; two, structural changes such as a luxuriant glycocalyx and the development of dense, long microvilli that are uniform in length owing to their coordinated connection and growth by Cadherin-related family member 2 (protocadherin-24) bridges9; third, enzyme expression related to the brush border of the villus and not crypt-residing cells, such as alkaline phosphatase, sucrase isomaltase and lactase; fourth, disappearance of the evidence of proliferation at 3–4 days after WNT3A removal, seen with the negative staining of Ki67 and EdU8; fifth, markedly increased amounts of MUC2 production, with a visible inner MUC2-positive mucus layer on 2D colonoid cultures that are up to 50 μM thick9 (FIG. 1b). The differentiation state described in BOX 2 is representative of the increased protein expression of the surface villus cells.

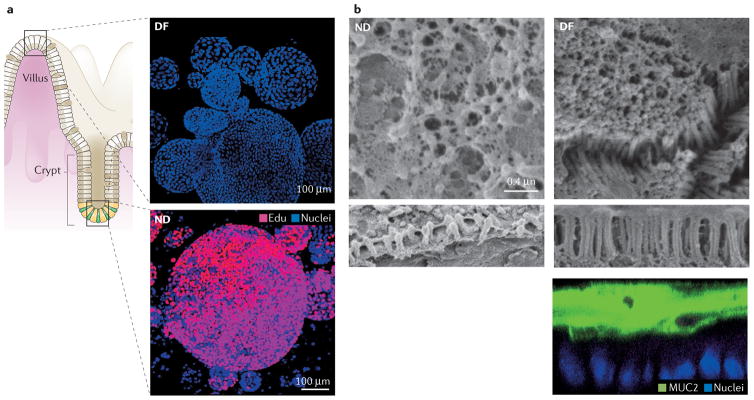

Figure 1. Human intestinal enteroids represent human intestinal tissue.

a | In high WNT3A media (bottom panel), the enteroids represent the non-differentiated (ND) crypt and transit-amplifying regions of the intestine and are mostly proliferative, EdU+ cells. Withdrawal of WNT3A (top panel) leads to differentiation (DF), represented by the surface cells and lack of proliferation. b | Human colonoids develop a uniform brush border and thick MUC2 mucus layer only upon differentiation. The left-hand panel shows a non-differentiated (ND; maintained in high WNT3A media) colon monolayer. Note that the brush border (bottom strip) is short and disorganized. The right-hand panel shows a differentiated (DF; lacking WNT3A media) colon monolayer with a dense, uniform brush border, the presence of intermicrovillar bridges (middle strip), and a thick MUC2 mucus layer overlaying the cells (bottom strip). Permission for parta obtained from Elsevier © Foule-Abel, J. et al. Gastroenterology 150, 638–649 (2016). Permission for part b obtained from Elsevier © In, J. et al. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2, 48–62 (2016).

Box 2. Differentiation of enteroids: proteins.

Brush border

↑ Protocadherin-24

↑ NHERF3

↑ NHE2

↑ Phospho-Ezrin

↑ Alkaline phosphatase

↑ Sucrase-isomaltase

↑ Lactase

Tight junction

↑ Occludin

Goblet cells

↑ MUC2

↑ TFF3

Enteroendocrine cells

↑ Chromogranin A

↑ Synaptophysin

Transporters

↔ NHE3

↔ CFTR

↓ NKCC1 (also known as SCL12A2)

↔ NBCe1 (also known as SLC4A4)

Stem cell markers/proliferation

↓ LGR5

↓ OLFM4

↓ ASCL2

↓ Ki67

The advantages of using enteroids and/or colonoids include segment specificity, the ability to study genetic diseases (as the adult stem cells from these cultures retain the identity of the donor), CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing41,44,45, potential uses for regenerating damaged intestinal tissue46, and potential for individualized drug screening and therapy47, a major boon for precision medicine. The disadvantages include an inability to study intestinal development from the embryonic stage and the lack of a mesenchyme34, immune cells and enteric nerves, thereby creating a need to re-implement all lacking intestinal components to mimic a complete human intestine (BOX 3).

Box 3. Key features of enteroids and colonoids.

Advantages

Time efficient, culture is quickly established (<1 week)

Retains intestinal segment specificity

Protein expression is stable over time

Transducable

Can use for high-throughput studies

Can use for physiological studies

Ideal for personalized medicine

Represents adult intestine

Disadvantages

Reductionist, only epithelia derived

Represents adult intestine

Unable to form villi

Lacks peristalsis and luminal and blood flow

Intestinal transport physiology

Current understanding of intestinal physiology has been derived from an amalgam of in vivo studies performed in rodents and human volunteers48–50, and ex vivo measurements performed with excised tissues from either animals and humans or cancer-derived cell lines51–57. The pitfalls of each model have been previously discussed, but the real lessons from these endeavours is that to answer a particular question, the model must be neither too complex nor too reductionist. Although ion transport is acknowledged to be influenced by multiple factors outside of epithelial cells, studies within a whole organism are often complicated and are not tractable, and experiments in overexpressed systems or immortal cell lines lack the full complement of normal cellular function and response. Enteroids and colonoids are a tractable model that are more representative of the human intestine than in vitro cell lines, and more easily handled than whole organism studies. These tissue-derived mini-intestines enable basic observations to be made and then be built upon as nonepithelial cell types are integrated into culture.

Functional ion transport physiology and pathophysiology has been demonstrated in 3D enteroids58,59 via assays for stimulated anion and/or fluid secretion and basal neutral sodium chloride (NaCl) absorption8. Stimulated luminal dilatation in enteroids is a powerful application that can be used to screen for secretory defects and potential therapies. The forskolin-induced swelling assay, in which increased cAMP triggers cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-mediated anion and fluid secretion into the closed lumen of the enteroid, was the first secretion study in human enteroids47 (FIG. 2a). Using the forskolin-induced swelling assay, CFTR correctors and potentiators could be assessed for efficacy in rectal colonoids derived from patients with cystic fibrosis to identify a combination of drugs that restore normal CFTR activity to otherwise non-responding enteroids. Swelling assays can also be performed with other secretagogues or ion transport inhibitors, such as carbachol and the enterotoxin domain of rotaviral protein NSP4 (REF. 60). The extent to which dilatation is diminished in the presence of specific ion transporter inhibitors indicates the relative contribution of a transporter to overall ion homeostasis8 and has resulted in a new model for active basal transport for both the undifferentiated (crypt and transit-amplifying regions) and differentiated (mature surface enterocytes) enteroids (FIG. 2b).

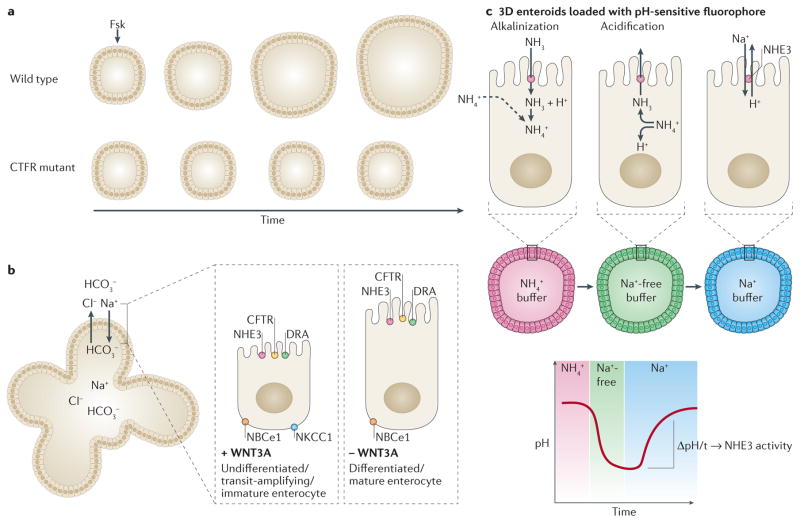

Figure 2. Enteroids can model transport physiology.

a | Enteroids generated from healthy individuals swell over time in the presence of forskolin (Fsk), but enteroids generated from patients with cystic fibrosis do not respond to forskolin-induced cAMP. b | Nondifferentiated, or crypt-like, enteroids share many of the same transporters as differentiated, or surface-like enteroids, with the exception of NKCC1.c | To measure sodium absorption via the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3), enteroids are loaded with a pH-sensitive fluorophore to monitor pH changes when exposed to various buffers. In the example shown, incubation in NH4+ buffer will lead to a basic pH and will be represented by the pH-dependent emission of a red fluorophore. Replacement of the buffer with a Na+-free buffer causes a sharp decrease to acidic pH and will be represented by emission of a green fluorophore. The pH is increased to basic levels by incubation in Na+ buffer. The change in pH over time indicates NHE3 activity of the enteroids.

The other major transport change in diarrhoeal diseases is decreased neutral NaCl absorption, which is assessed by measuring the rate of Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity using a pH-sensitive ratiometric fluorophore and multiphoton microscopy8,61 (FIG. 2c). The assay consists of NH4Cl prepulse, Na+-free incubation to induce acid loading and reintroduction of Na+ to induce pH recovery to baseline conditions. Duodenal enteroids exhibited the expected response to NHE3 inhibitors, enterotoxins and second messengers in this transport assay8.

Host–pathogen interactions

Although the number and severity of enteric pathogen outbreaks is substantially decreasing worldwide (from 800,000 to 250,000 deaths per year) owing to the use of oral rehydration solution, new vaccine developments and improved sanitation, many bacteria and viruses continue to cause life-threatening epidemics in developing and developed countries62,63. Even though the per patient frequency of diarrhoea is decreasing, because of the increasing population in developing countries, the number of diarrhoea cases per year is increasing or staying near constant. This problem is evidenced by deaths from outbreaks of Vibrio cholerae in Haiti64 (with ~10,000 deaths), Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli in Europe and the USA65–67, and the considerable increase in the numbers of Clostridium difficile cases in hospitals68–70. No specific FDA-approved therapies exist against these and other enteric pathogens. Increased use of antibiotics often leads to greater harm rather than a cure by selecting for antibiotic-resistant ‘super-bugs’ and/or highly toxigenic strains, as well as causing bacteria to increase the release of luminal virulence factors71–74. As discussed, a major hurdle that has contributed to the lack of specific treatments for many enteric-pathogen-caused illnesses is the absence of a physiologically relevant preclinical intestinal model of pathogen-induced human disease. Although numerous animal models have been used to study human enteric pathogens, they have not provided a breakthrough in understanding the complexity of intestinal damage nor led to the development of successful therapeutic interventions75. Both HIOs and enteroid or colonoid cultures are quickly gaining a role as an indispensable model for host–pathogen interactions. The interactions of enteric pathogens — such as C. difficile, Salmonella enterica, rotavirus and entero-haemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) — with the human intestinal epithelia have already been demonstrated using these models (TABLE 1). Use of these models enables, for the first time, elucidation of the varying roles that the complex ecosystem of t intestinal epithelial cell types have in pathogen colonization, replication, host damage and clearance of infection.

Table 1.

Infection studies using intestinal organoids or enteroids

| Pathogen | Organoid or enteroid | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Clostridium difficile | iPS organoid | 76,77,78 |

| Salmonella enterica | iPS organoid | 80 |

| Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli |

|

9,83 |

| Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli |

|

83 |

| Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli |

|

83 |

| Helicobacter pylori |

|

87,88, 90,98 |

| Cholera toxin (Vibrio cholerae) |

|

8,47 |

| Heat-stable enterotoxin A (enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli) | Human jejunal enteroid | 8 |

| Rotavirus |

|

60,81,82 |

iPS, induced pluripotent stem cell.

For example, the role of mucus76 and paracellular dysfunction77 in C. difficile infection (CDI) has been studied using HIOs microinjected with C. difficile. Although C. difficile alone was sufficient to reduce the production of MUC2 (a major gel-forming mucin), it was not capable of altering the mucus oligosaccharide composition76. Additionally, using HIOs to improve understanding of the mechanisms contributing to diarrhoea induced by C. difficile found substantial transcriptional downregulation of the major sodium absorbing protein NHE3 (REF. 78). These data might explain the high sodium concentrations found in the stool of patients with CDI78,79. However, C. difficile is primarily a colonic infection, which can lead to colitis. The above-mentioned studies were all performed in HIOs, a disadvantage in that they are fetal-like and do not model the adult colon. To avoid confounding results, future intestinal host–pathogen studies need to be modelled in the accurate intestinal segment.

HIOs seem to be a promising model to explore the interaction of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium with the human intestinal epithelium80. Salmonella microinjected into the lumen of HIOs was able to invade the epithelial barrier and take up residence within Salmonella-containing vacuoles, as well as change the transcriptional profile of the host, including altering the patterns of cytokine expression after exposure to bacteria.

Both human proximal small intestinal enteroids and HIOs have been shown to model human rotavirus infection39,60,81,82. Rotavirus replicates and produces infectious virions in enteroids and HIOs, with viral replication increasing over 96 h60,82. Moreover, an increased degree of infection (~50%) in differentiated human enteroids exposed to human rotavirus has been demonstrated compared to simian strains60. Differentiated enteroids are comprised of mature epithelial cells that normally reside in the upper region of small intestinal villi and have been shown to be the site where rotavirus infection occurs8. Additionally, rotavirus antigen was found in entero-endocrine cells, suggesting the importance of serotonin production in rotavirus-induced diarrhoea and pathogenesis60. Human enteroids provide the only model intestinal system that will enable future studies on specific subsets of enteroendocrine cells and their importance during rotavirus infection. Rotavirus infection causes rapid dilation of the enteroid lumen as well as inhibition of NHE3, which might be an important contributor to rotavirus-induced diarrhoea (modelled in FIG. 3)36. Given that the pathophysiology of rotavirus-induced diarrhoea remains poorly understood, the technological advancement of growing enteroids as monolayers, in addition to the already described 3D assays, enables mechanistic investigation and identification of the ion and water transporters affected by rotavirus infection.

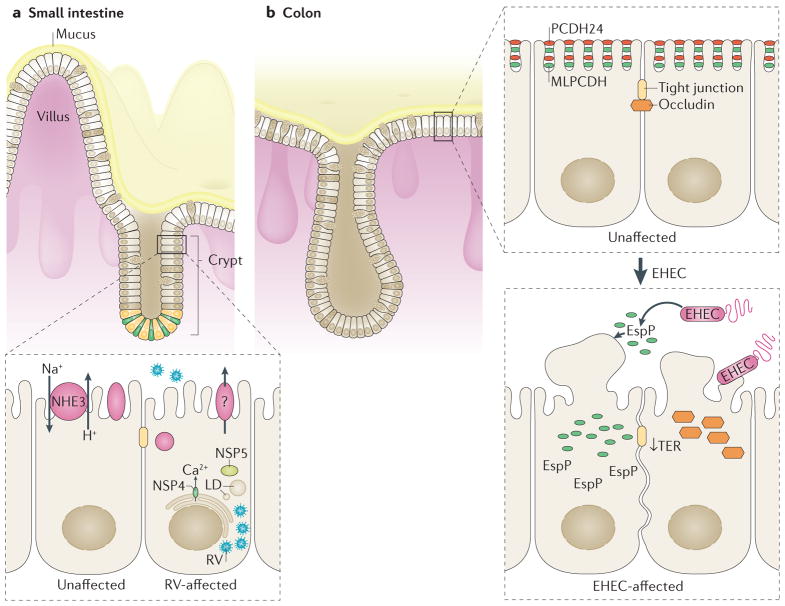

Figure 3. Small intestinal and colonic enteroids can form a 2D monolayer and present a novel model to study intestinal–enteric pathogen interactions.

a | Small intestinal enteroids are readily infected by rotavirus (RV), as noted by the presence of viral particles and lipid droplets (LD) in enteroids during RV infection. RV inhibits NHE3 (Na+/H+ exchanger 3), which might contribute to RV-induced diarrhoea. b | Colonoids infected with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) lead to a sharp decrease in transepithelial electrical resistance (TER), the degradation of brush border protein PCDH24, mislocalization of brush border protein MLPCDH (mucin-like protocadherin) and mislocalization of junctional protein occludin. The importance of EspP, an EHEC secreted serine protease, in advancing EHEC infection was first reported using human colonoid monolayers.

The topographical nature of 3D Matrigel (Corning Life Sciences, USA)-embedded intestinal cultures presents limitations for their use in studying epithelium–pathogen interactions. Enteroid size, number of cells per enteroid and luminal volumes can vary. Additionally, the enteroids have restricted luminal access, thus requiring microinjection of the pathogen into the lumen of each individual enteroid or organoid. We and others9,39,83 are pioneering an innovative model of host–pathogen interactions using human enteroid or colonoid monolayers. This 2D model takes advantage of the stability of the 3D enteroids and colonoids to fragment the 3D cultures and grow them as a monolayer on semipermeable supports, enabling apical exposure to pathogens. The differentiated monolayers expresses all major cell types present in the small intestine and colonic epithelium83 and in 3D cultures, including enterocytes, colonocytes, enteroendocrine and mucin-producing goblet cells. The monolayers enable controlled access to both apical and basolateral surfaces to facilitate highly reproducible measurements of pathogen–epithelial interactions that are restricted in the 3D spherical cultures. This tractable 2D model enables ex vivo monitoring of the initial steps (several hours postinfection) in the interaction between Shiga-toxin-producing EHEC and the human colonic epithelium, a feat not achieved in whole animal models9. Given that differentiated human colonoid monolayers produce a thick, impermeable mucus layer (FIG. 1b), as described in in vivo human colon84,85, they present a more physiologically relevant model for EHEC infection. Indeed, a novel finding showed that EHEC destroys the inner mucus layer, using the mucus as a high-energy substrate for colonization and possibly as an initial anchor9,26. The human colonoid monolayer presents a novel tool to study the interactions of the colonic mucus with enteric pathogens and the commensal flora, which do not have the ability to degrade mucus, and also enables validation of previously studied phenotypes of EHEC infection, such as occludin mislocalization and brush border degradation (FIG. 3). Human enteroid and colonoid monolayers are undergoing validation as a physiologically relevant model to identify the individual genetic differences in host–pathogen interactions, and assess and predict the changes in epithelial permeability and drug absorption and/or metabolism in normal physiology versus enteric infections.

Other gastrointestinal tract organoids

The success of small intestinal and colonic mini-guts has led to the culturing of other organs along the digestive tract86–94. For example, similar to the intestine, relevant gastric models are lacking90. Most gastric in vitro cell lines are derived from gastric cancer95, and therefore do not represent normal gastric epithelium. Primary gastric cultures can be obtained but were unable to be expanded in vitro, possibly due to the lack of appropriate growth factors, resulting in short-lived cultures unsuitable for extensive physiological or pathophysiological studies96. However, preliminary studies with gastric organoids have found that they represent a novel pathophysiological model for the study of host response to Helicobacter pylori infection88. Similarly to the intestinal cultures, gastric organoids can be generated from either iPS90 or adult stem cells isolated from surgical sections of the gastric corpus87.

iPS cells differentiated into endoderm are generated into the foregut with the addition of WNT3A, FGF, and Noggin90. These growth factors enable SOX-2 expression but CDX2 repression, thus preventing hindgut formation. Addition of retinoic acid to the foregut spheroids causes an increase in PDX-1 expression, resulting in high PDX-1 and SOX-2 expression and differentiation into the segment-specific antrum. Addition of EGF causes further differentiation from immature antral spheroids to mature antral organoids that form glandular and pit-like structures90. Interestingly, RNA sequencing showed that iPS-derived gastric organoids maintain a similar transcriptional profile as human fetal stomach90. By contrast, gastric organoids derived from adult stem cells maintain their adult characteristics throughout culture and differentiation87,88. Culture conditions do not affect histology or cause chromosomal aberrations, as normal or tumour-derived sections continued as normal or tumour-derived organoids, respectively87. Similar to the iPS-derived gastric organoids, these cultures also require temporal addition or removal of various growth factors for both long-term maintenance and differentiation into either glandular or pit structures.

Regardless of origin, both types of gastric organoids respond to H. pylori infection. H. pylori is a common gastric pathogen that can cause severe peptic ulcers97. Given that H. pylori resides in the gastric lumen, 3D organoids were microinjected with H. pylori to mimic infection. After a short-term infection (2 h), the gastric organoid upregulates genes associated with pro-inflammatory pathways, known host responses to H. pylori infection87,90. Further studies have validated human-derived fundic gastric organoids (hFGOs) as a functional model of H. pylori infection in a study focusing on CagA (an important virulence factor for H. pylori), its receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met and the cell surface adhesion molecule CD44. The proliferative response was blocked in hFGOs microinjected with a ΔcagA mutant strain or exposed to a c-Met inhibitor before infection with wild-type H. pylori98. CD44, a co-receptor for c-Met and putative gastric cancer stem cell marker99, was shown to have a role in the proliferative response to H. pylori infection. These initial studies highlight the physiological importance of human gastric organoids over other gastric models in understanding gastric development and pathogenicity of H. pylori.

In addition, hepatic organoids from human iPS cells and human adult bile duct cells have been successfully cultured and maintained in vitro93,94,100. However, the architectural complexity of the mature adult liver has limited these functional physiology and pathophysiology assays. Although liver organoids can mimic the disease phenotype of the patient94, they represent parenchymal hepatocytes and do not develop into stellate cells, cholangiocytes and other cells that comprise the mature liver. Human iPS cells can be directed towards hepatic differentiation and co-cultured with endothelial and mesenchymal stem cells to form a primitive liver bud100. Another approach uses human iPS cells and manipulation of GATA-6 levels to co-differentiate into parenchymal hepatocytes and stromal cells to form a more complex liver bud92. Both approaches enable the study of hepatic development from the embryonic state but the organoids remain fetal in nature when differentiated into liver buds. Hepatic organoids from human adult bile duct cells retain the genetic signature of the donor94, opening up possibilities of regenerative medicine and specific host–pathogen interaction. Although no studies have yet detailed pathophysiology using hepatic organoids, the success of several groups in generating stable and long-term hepatic cultures suggests these studies are not far behind.

Future challenges

The use of human gastrointestinal mini-intestines (encompassing iPS-derived or tissue-derived enteroids and colonoids) has led to rapid advances in understanding intestinal development, physiology and pathophysiology. However, numerous challenges will need to be addressed. Both intestinal-tissue-derived and iPS-derived mini-intestines represent a reductionist model. Although more complex than in vitro intestinal and colonic cell lines, they do not fully represent the human digestive tract in vivo. For example, they lack vasculature, an enteric nervous system and resident microbiota. The advancement of a 2D human organoid system might enable these components to be added individually, in a sandwich-style model, but will also require a representative basal media. Adding microbiota will require an oxygen gradient, another component currently lacking from this model.

The intestinal-tissue-derived enteroids or colonoids have been shown to retain ‘patient specificity’, even over multiple passages44,47. This phenomenon has incredible potential for personalized, or precision, medicine, and future drug development studies. However, these heterogeneous populations present an interesting challenge for drug discovery assays. Whether iPS-derived organoids will be able to compensate as a uniform intestinal model for future drug discovery remains to be discovered. Both the enteroid, colonoid and iPS organoid models require further characterization as to their specific advantages for drug discovery, drug development, and individualized precision medicine. The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 as a genetic modification tool to correct mutations44 provides an exciting future in precision gene therapy and intestinal transplantation.

Conclusions

The gastrointestinal organoids and enteroids and/or colonoids present a novel model that has led to discoveries in homeostatic intestinal physiology and interactions between enteric pathogens and host intestinal epithelia. Basal or stimulated ion secretion and absorption can be measured using both the 2D and 3D enteroid cultures. To minimize cellular injury, enteroids and colonoids can be directed to a 2D morphology with direct access to the apical surface. This approach enables direct host–pathogen studies at the earliest stages of infection in a functionally and physiologically relevant human model. Use of this model might lead to novel pathophysiological interactions, which will advance curative or preventive therapies for enteric infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ research is supported by NIH grants K01DK106323 (J.G.I.), R01DK026523 (M.D.), R01DK061765(M.D.), P30DK089502 (M.D.), T32DK007632 (M.D.), UH3TR000503 (M.D.), UH3TR000504 (M.D.), U01DK10316 (M.K.E.), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation: Grand Challenges (M.D., O.K., M.K.E.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.D. and J.G.I. researched data, contributed to discussion of content and writing, and reviewed/edited the manuscript before submission. J.F.-A. researched data for the article and contributed to writing. M.K.E. reviewed/edited the manuscript before submission. N.C.Z. and O.K. researched data for the article and contributed to discussion of content and writing.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Seidler UE. Gastrointestinal HCO3− transport and epithelial protection in the gut: new techniques, transport pathways and regulatory pathways. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:900–908. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canny GO, McCormick BA. Bacteria in the intestine, helpful residents or enemies from within? Infect Immun. 2008;76:3360–33738. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00187-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heath JP. Epithelial cell migration in the intestine. Cell Biol Int. 1996;20:139–146. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng H, Bjerknes M. Whole population cell kinetics and postnatal development of the mouse intestinal epithelium. Anat Rec. 1985;211:420–426. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker N. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;15:19–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artursson P. Epithelial transport of drugs in cell culture. I: a model for studying the passive diffusion of drugs over intestinal absorptive (Caco-2) cells. J Pharm Sci. 1990;79:476–482. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600790604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middendorp S, et al. Adult stem cells in the small intestine are intrinsically programmed with their location-specific function. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/stem.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foulke-Abel J, et al. Human enteroids as a model of upper small intestinal ion transport physiology and pathophysiology. Gastroenterology. 2015;150:638–649. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.In J, et al. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli reduces mucus and intermicrovillar bridges in human stem cell-derived colonoids. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2:48–62.e43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCracken KW, Howell JC, Wells JM, Spence JR. Generating human intestinal tissue from pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1920–1928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato T, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casburn-Jones AC. Management of infectious diarrhoea. Gut. 2004;53:296–305. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiagarajah JR, Donowitz M, Verkman AS. Secretory diarrhoea: mechanisms and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:446–457. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilgers AR, Conradi RA, Burton PS. Caco-2 cell monolayers as a model for drug transport across the intestinal mucosa. Pharm Res. 1990;7:902–910. doi: 10.1023/a:1015937605100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nataro JP, Hicks S, Phillips AD, Vial PA, Sears CL. T84 cells in culture as a model for enteroaggregative Escherichia coli pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4761–4768. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4761-4768.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huet C, Sahuquillo-Merino C, Coudrier E, Louvard D. Absorptive and mucus-secreting subclones isolated from a multipotent intestinal cell line (HT-29) provide new models for cell polarity and terminal differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:345–357. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larregieu CA, Benet LZ. Drug discovery and regulatory considerations for improving in silico and in vitro predictions that use Caco-2 as a surrogate for human intestinal permeability measurements. AAPS J. 2013;15:483–497. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun D, et al. Comparison of human duodenum and Caco-2 gene expression profiles for 12,000 gene sequences tags and correlation with permeability of 26 drugs. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1400–1416. doi: 10.1023/a:1020483911355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awortwe C, Fasinu PS, Rosenkranz B. Application of Caco-2 cell line in herb–drug interaction studies: current approaches and challenges. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;17:1–19. doi: 10.18433/j30k63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Artursson P, Palm K, Luthman K. Caco-2 monolayers in experimental and theoretical predictions of drug transport. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:27–43. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes P, Marshall D, Reid Y, Parkes H, Gelber C. The costs of using unauthenticated, over-passaged cell lines: how much more data do we need? BioTechniques. 2007;43:575–586. doi: 10.2144/000112598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markert T, et al. Endogenous expression of type II cGMP-dependent protein kinase mRNA and protein in rat intestine. Implications for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:822–830. doi: 10.1172/JCI118128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaandrager AB, et al. Differential role of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase II in ion transport in murine small intestine and colon. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:108–114. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Mark VA, et al. The lipid flippase heterodimer ATP8B1–CDC50A is essential for surface expression of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (SLC10A2/ASBT) in intestinal Caco-2 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:2378–2386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson MEV, et al. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erdem AL, Avelino F, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Giron JA. Host protein binding and adhesive properties of H6 and H7 flagella of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7426–7435. doi: 10.1128/JB.00464-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacheco AR, et al. Fucose sensing regulates bacterial intestinal colonization. Nature. 2012;492:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature11623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spence JR, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkbeiner SR, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis reveals hallmarks of human intestine development and maturation in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:1140–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson CL, et al. An in vivo model of human small intestine using pluripotent stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:1310–1314. doi: 10.1038/nm.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells JM, Spence JR. How to make an intestine. Development. 2014;141:752–760. doi: 10.1242/dev.097386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinagoga KL, Wells JM. Generating human intestinal tissues from pluripotent stem cells to study development and disease. EMBO J. 2015;34:1149–1163. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stelzner M, et al. A nomenclature for intestinal in vitro cultures. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1359–G1363. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00493.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato T, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2010;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zachos NC, et al. Human enteroids/colonoids and intestinal organoids functionally recapitulate normal intestinal physiology and pathophysiology. J Biol Chem. 2015;291:3759–3766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.635995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato T, Clevers H. Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: mechanism and applications. Science. 2013;340:1190–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1234852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovbasnjuk O, et al. Human enteroids: preclinical models of non-inflammatory diarrhea. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/scrt364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foulke-Abel J, et al. Human enteroids as an ex-vivo model of host-pathogen interactions in the gastrointestinal tract. Exp Biol Med. 2014;239:1124–1134. doi: 10.1177/1535370214529398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujii M, Matano M, Nanki K, Sato T. Efficient genetic engineering of human intestinal organoids using electroporation. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1474–1485. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drost J, et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature. 2015;521:43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature14415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Date S, Sato T. Mini-gut organoids: reconstitution of stem cell niche. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2015;31:269–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Lau W, et al. Peyer’s patch M cells derived from Lgr5+ stem cells require SpiB and are induced by RankL in cultured “miniguts”. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:3639–3647. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00434-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwank G, et al. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matano M, et al. Modeling colorectal cancer using CRISPR–Cas9-mediated engineering of human intestinal organoids. Nat Med. 2015;21:256–262. doi: 10.1038/nm.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yui S, et al. Functional engraftment of colon epithelium expanded in vitro from a single adult Lgr5+ stem cell. Nat Med. 2012;18:618–623. doi: 10.1038/nm.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dekkers JF, et al. A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nat Med. 2013;19:939–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turnberg LA, Bieberdorf FA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Interrelationships of chloride, bicarbonate, sodium, and hydrogen transport in the human ileum. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:557–567. doi: 10.1172/JCI106266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turnberg LA, Fordtran JS, Carter NW, Rector FC. Mechanism of bicarbonate absorption and its relationship to sodium transport in the human jejunum. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:548–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI106265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kunzelmann K, Mall M. Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon: mechanisms and implications for disease. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:245–289. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frizzell RA, Field M, Schultz SG. Sodium-coupled chloride transport by epithelial tissues. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1979;236:F1–F8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.236.1.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Field M, Fromm D, Al-Awqati Q, Greenough WB. Effect of cholera enterotoxin on ion transport across isolated ileal mucosa. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:796–804. doi: 10.1172/JCI106874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Field M, Graf LH, Jr, Laird WJ, Smith PL. Heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli: in vitro effects on guanylate cyclase activity, cyclic GMP concentration, and ion transport in small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2800–2804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dharmsathaphorn K, Mandel KG, Masui H, McRoberts JA. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-induced chloride secretion by a colonic epithelial cell line. Direct participation of a basolaterally localized Na+, K+, Cl− cotransport system. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:462–471. doi: 10.1172/JCI111721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandel KG, Dharmsathaphorn K, McRoberts JA. Characterization of a cyclic AMP-activated Cl− tranport pathway in the apical membrane of a human colonic epithelial cell line. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:704–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dharmsathaphorn K, Pandol SJ. Mechanism of chloride secretion induced by carbachol in a colonic epithelial cell line. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:348–354. doi: 10.1172/JCI112311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Musch MW, Arvans DL, Wu GD, Chang EB. Functional coupling of the downregulated in adenoma Cl−/base exchanger DRA and the apical Na+/H+ exchangers NHE2 and NHE3. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G202–G210. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90350.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mizutani T, et al. Real-time analysis of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport across primary intestinal epithelium three-dimensionally cultured in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grant CN, et al. Human and mouse tissue-engineered small intestine both demonstrate digestive and absorptive function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;308:G664–G677. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00111.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saxena K, et al. Human intestinal enteroids: a new model to study human rotavirus infection, host restriction, and pathophysiology. J Virol. 2016;90:43–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01930-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walker NM, et al. Cellular chloride and bicarbonate retention alters intracellular pH regulation in Cftr KO crypt epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;310:G70–G80. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00236.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abba K, Sinfield R, Hart CA, Garner P. Pathogens associated with persistent diarrhoea in children in low and middle income countries: systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fletcher SM, McLaws ML, Ellis JT. Prevalence of gastrointestinal pathogens in developed and developing countries: systemic review and meta-analysis. J Public Health Res. 2013;2:42–53. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2013.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Page AL, et al. Geographic distribution and mortality risk factors during the cholera outbreak in a rural region of Haiti, 2010–2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jenkins C, et al. Public health investigation of two outbreaks of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 associated with consumption of watercress. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:3946–3952. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04188-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luna-Gierke RE, et al. Outbreaks of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection: USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:2270–2280. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813003233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Navarro-Garcia F. Escherichia coli O104:H4 pathogenesis: an enteroaggregative E. coli/Shiga toxin-producing E. coli explosive cocktail of high virulence. Microbiol Spectr. 2014;2:533–539. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0008-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Warny M, et al. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet. 2005;366:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martinez F. Clostridium difficile outbreaks: prevention and treatment strategies. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2012;5:55–64. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S13053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown K, Valenta K, Fisman D, Simor A, Daneman N. Hospital ward antibiotic prescribing and the risks of Clostridium difficile Infection. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:626–633. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74:417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garner CD, et al. Perturbation of the small intestine microbial ecology by streptomycin alters pathology in a Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium murine model of infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2691–2702. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01570-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hodges K, Gill R. Infectious diarrhea cellular and molecular mechanisms. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:4–21. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.1.11036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Willing BP, Russell SL, Finlay BB. Shifting the balance: antibiotic effects on host–microbiota mutualism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:233–243. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiminez JA, Uwiera TC, Douglas Inglis G, Uwiera RRE. Animal models to study acute and chronic intestinal inflammation in mammals. Gut Pathog. 2015;7:29. doi: 10.1186/s13099-015-0076-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Engevik MA, et al. Human Clostridium difficile infection: altered mucus production and composition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;308:G510–G524. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00091.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leslie JL, et al. Persistence and toxin production by Clostridium difficile within human intestinal organoids result in disruption of epithelial paracellular barrier function. Infect Immun. 2015;83:138–145. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02561-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Engevik MA, et al. Human Clostridium difficile infection: inhibition of NHE3 and microbiota profile. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;308:G497–G509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00090.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hayashi H, et al. Inhibition and redistribution of NHE3, the apical Na+/H+ exchanger, by Clostridium difficile toxin B. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:491–504. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Forbester JL, et al. Interaction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with intestinal organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Infect Immun. 2015;83:2926–2934. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00161-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Finkbeiner SR, et al. Stem cell-derived human intestinal organoids as an infection model for rotaviruses. mBio. 2012;3:e00159–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00159-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yin Y, et al. Modeling rotavirus infection and antiviral therapy using primary intestinal organoids. Antiviral Res. 2015;123:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.VanDussen KL, et al. Development of an enhanced human gastrointestinal epithelial culture system to facilitate patient-based assays. Gut. 2015;64:911–920. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ermund A, Schutte A, Johansson MEV, Gustafsson JK, Hansson GC. Studies of mucus in mouse stomach, small intestine, and colon. I Gastrointestinal mucus layers have different properties depending on location as well as over the Peyer’s patches. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G341–G347. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00046.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Johansson MEV, Sjövall H, Hansson GC. The gastrointestinal mucus system in health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:352–361. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stange, Daniel E, et al. Differentiated Troy+ chief cells act as reserve stem cells to generate all lineages of the stomach epithelium. Cell. 2013;155:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bartfeld S, et al. In vitro expansion of human gastric epithelial stem cells and their responses to bacterial infection. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:126–136.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schlaermann P, et al. A novel human gastric primary cell culture system for modelling Helicobacter pylori infection in vitro. Gut. 2014;65:202–213. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barker N, et al. Lgr5+ve stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McCracken KW, et al. Modelling human development and disease in pluripotent stem-cell-derived gastric organoids. Nature. 2014;516:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen YJ, et al. De novo formation of insulin-producing “neo-β cell islets” from intestinal crypts. Cell Rep. 2014;6:1046–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Guye P, et al. Genetically engineering self-organization of human pluripotent stem cells into a liver bud-like tissue using Gata6. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10243. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huch M, et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huch M, et al. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell. 2014;160:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Park JG, et al. Characteristics of cell lines established from human gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2773–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leite M, Figueiredo CA. Method for short-term culture of human gastric epithelial cells to study the effects of Helicobacter pylori. 2012;921:61–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-005-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5191–204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bertaux-Skeirik N, et al. CD44 plays a functional role in Helicobacter pylori-induced epithelial cell proliferation. PLOS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004663. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Takaishi S, et al. Identification of gastric cancer stem cells using the cell surface marker CD44. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1006–1020. doi: 10.1002/stem.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Takebe T, et al. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature. 2013;499:481–484. doi: 10.1038/nature12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]