Introduction

The occurrence of symptomatic maternal arrhythmias during pregnancy is a cause of concern for the well-being of both the mother and the fetus. In women of reproductive age, the commonest arrhythmia is paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). SVT in pregnancy is defined as any tachyarrhythmia with a heart rate greater than 120 beats/min [1]. There are no reliable data on the incidence of paroxysmal SVT in pregnant women. The incidence in the general population is 35 per 1,00,000 person-years [2]. Over half of these patients are asymptomatic. The main mechanism for the development of SVT is via reentry (atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia in 60 % of cases and atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia in 30 % cases) [3].

Episodes of SVT occur with increased frequency during pregnancy particulary in third trimester. Proposed mechanisms include the hyperdynamic circulation, the altered hormonal milieu, increased circulating levels of catecholamines, increased adrenergic receptor sensitivity and increased maternal effective circulating volume causing atrial stretch [4, 5]. Potential risk factor for SVT in pregnancy is underlying congenital or structural heart disease [6]. In most cases, there is no history of heart disease.

Physical treatment like sinus carotid massage or Valsalva maneuvers followed by drug therapy is tried in hemodynamically stable patients. In cases of failure of above measure or when there is hemodynamic compromise, electrical cardioversion or invasive method like radiofrequency ablation is justified, which may jeopardize the mother and her fetus. No large-scale studies or randomized control trials regarding safety of ECV in pregnancy and agents for successful cardioversion are available [7]. The recommendations published by American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines/European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines are solely based on expert consensus [8].

We present a case of maternal SVT with hemodynamic instability which failed to respond to physical and drug therapy.

Case Report

A 30-year-old female G2P1L1 with 37 weeks of gestation came with complaints of sudden onset palpitations, uneasiness and vague dull aching chest pain associated with pain in left upper limb. She had history of one previous normal vaginal delivery 7 years back without any complications.

In the present pregnancy at 26 weeks of gestation, patient had similar complaints of sudden onset palpitations, uneasiness and dull aching chest pain. She had no previous history of any major medical illness particularly any cardiac or pulmonary disease presenting with such complaints or any surgical interventions in past. She was admitted, and the clinical examination showed a pulse rate of 220/min with electrocardiogram (ECG) showing presence of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) but with hemodynamic stability (BP-140/70 mm of Hg). Anemia and hyperthyroidism were excluded. 2D echocardiography revealed no structural heart abnormality. With cardiology consultation, patient was reverted to normal sinus rhythm with the help of IV adenosine (total dose of 12 mg divided in two doses) at that time. After the stabilization of heart rate, she was discharged on low-dose labetalol (25 mg BD). Then till date, she was following up regularly and the antenatal period was uneventful.

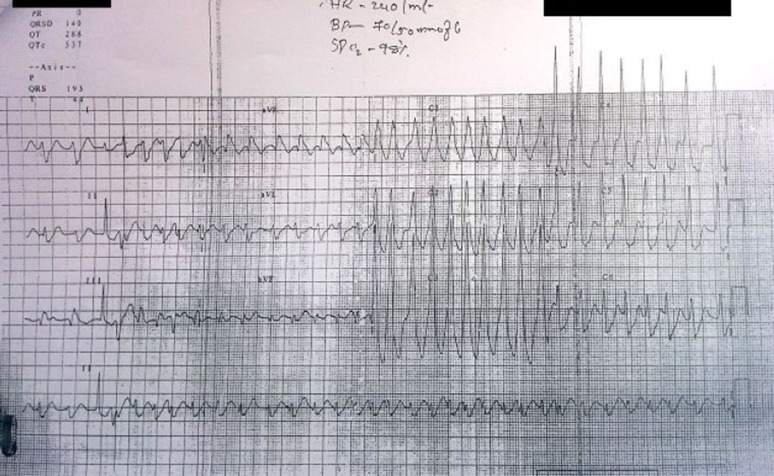

Patient was taking all medication as advised and had not missed any dose. In spite of this, at the gestational age of 37 weeks of pregnancy she had sudden onset of palpitations and feeling of uneasiness when she was asleep. She woke up because of persistent palpitations and chest pain associated with dull aching pain in left upper limb within few minutes. Immediately, relatives brought patient to our hospital. Clinical examination revealed patient had irregular pulse rate of 242 beats/min. Blood pressure was 70/50 mm of Hg. There was no pedal edema, and auscultation of lung was normal. Auscultation of heart revealed tachycardia. She had no h/o giddiness, syncopal attack, dyspnea, cough, fever, bleeding or leaking per vaginally. The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed SVT, particularly o-AVNRT (orthodromic AV nodal reentrant tachycardia) with ventricular rate of 240 beats/min (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) showing supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

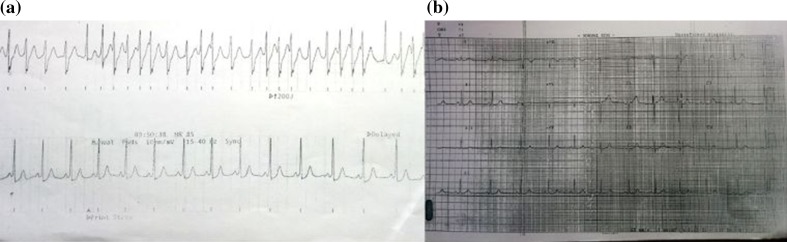

Patient was admitted in ICU immediately with simultaneous application of physical therapy like carotid sinus massage and Valsalva maneuver. Urgent help from cardiology people was sought. Immediately, two peripheral lines were secured with large bore I.V. cannulas, and all the necessary investigations sent. Still patient had persistent heart rate around 222 beats/min and BP—70/50 mm of hg. Anemia and hyperthyroidism had already been excluded and reconfirmed with investigations. Repeat 2D echocardiography confirmed no structural heart abnormality. IV adenosine 12 mg bolus was given, and same dose was repeated again after 10 min. IV fluids and IV amiodarone 150 mg over 30 min were given. Central line was put. In spite of all efforts, patient had still tachycardia of around 220 beats/min with hemodynamic instability and persistent symptoms. Under careful fetal and maternal monitoring, ECV was performed with 200 J energy. This reverted patient’s heart rate immediately to 85 beats/min which settled to 68 beats/min and BP of 100/70 mm of Hg within 10 min (Fig. 2a). On the same day, cesarean section was done under general anesthesia and she delivered male baby of birth weight 2.46 kg with APGAR score of 7/10 and 10/10 at 1 and 5 min postpartum. Intra-operatively, there were no complications. Postoperative patient was kept in ICU under monitoring and was hemodynamically stable. The neonate was evaluated, and no structural or functional abnormality detected in neonate.

Fig. 2.

a Electrocardioversion (ECV) with energy 200 J applied and ECG post-ECV. b Normal ECG after ECV and radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

On day 3 post-op, cardiologist took decision of radiofrequency ablation (RFA). She underwent successful RFA via right femoral route. Post-procedure, patient was stable and shifted to ward (Fig. 2b). On follow-up, patient and neonate, both are stable. No repeat episodes of SVT observed till 2 year postpartum, i.e., the time of last follow-up.

Discussion

Both mother and fetus are at risk when SVT occurs during pregnancy. Pregnancy may predispose to and exacerbate symptoms of SVT which are shortness of breath, palpitations, dizziness and presyncope. Clinical assessment of vital signs and 12-lead ECG investigation are mandatory for an accurate diagnosis of arrhythmia [7, 9]. Echocardiography is essential to exclude structural and functional heart diseases as the presence of organic heart diseases is an important risk factor for arrhythmias during pregnancy. Early involvement of cardiologist is recommended to diagnose SVT and to detect any underlying etiology which can be life-threatening. Close collaboration between the cardiologist and the obstetrician is important throughout the pregnancy as well as puerperium to develop care strategies for potential recurrences of SVT [3, 7, 9].

The acute management of SVT in pregnancy remains a difficult clinical challenge as the available data are limited to observational studies and case reports. The decision must be taken with appropriate consideration of both maternal and fetal factors. Monitoring of both mother and fetus should be continued during acute treatment. In stable patients, noninvasive maneuvers like carotid massage or Valsalva maneuver with simultaneous positioning the patient in the left lateral position, administering 100 % oxygen and establishing intravenous access should be first attempted. In case of failure with physical procedures, first-line pharmacological treatment is adenosine, followed by low dose of β-blockers. Second choice is verapamil but only after the first trimester of pregnancy and only in acute circumstances. When drugs fail or in case of life-threatening symptoms such as shock and pulmonary edema, ECV is indicated.

There are less than 50 cases reported that describe the use of ECV during pregnancy [7] and less than 20 cases reported use of ECV particularly for SVT in pregnancy [3]. There is considerable variation in required energy varied from 50 to 400 J. Successful ECV during pregnancy after one or more attempts is reported in 67–93 % which is comparable to non-pregnant population (42–92 %) [3, 7]. While in 4–6 % of cases, adverse maternal outcome was reported which was attributed to underlying heart disease. There are limited data on perinatal outcome. However, it is supposed that there is little effect on fetal heart because of high fibrillation threshold of a small heart and only minimum current reaching uterus as uterus is not involved in the ECV trajectory. However, caution should be applied since the hyperemic uterine muscles as well as amniotic fluid are excellent conductors of electricity. Only 1 case with fetal adverse outcome and 2 cases with fetal bradycardia mostly attributed to hypertonic uterus requiring immediate cesarean delivery are reported [3, 7].

So, our case highlights that multidisciplinary approach, regular follow-up, prompt and correct diagnosis, proper use of physiological treatment and drugs such as adenosine and ECV if needed with proper maternal and fetal monitoring especially continuously during ECV are the key for successful management of SVT in pregnancy.

Dr. Rekha V. Agrawal

is currently Consultant Obstetrician and Gynecologist at Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, and has experience of over 25 years of practice. She has completed her graduation and M.D., D.G.O., F.C.P.S., D.N.B. from Bombay. Her areas of interest are laparoscopic surgeries and complete, comprehensive, scientific management of high-risk pregnancy. She also has a vast experience in management of adolescent and menopausal patients.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Patient has given consent for publishing photograph, clinical history and management of the same and was assured that anonymity will be preserved.

Footnotes

Dr. Rekha Agrawal is Consultant in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre; Dr. Hemant Shintre is Post-Diploma DNB Resident (Final year) in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai; Dr. Bindu Rani is DNB Resident (JR), in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre.

References

- 1.Nelson-Piercy C, Handook of obstetric medicine, 2nd ed. Martin dunitz, London. 2002.

- 2.Orejarena LA, Vidaillet H, Jr, DeStefano F, et al. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(1):150–157. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh N, Luk A, Derzko C, et al. The acute treatment of maternal supraventricular tachycardias during pregnancy: a review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oktay C, Kesapli M, Altekin E. Wide-QRS complex tachycardia during pregnancy: treatment with cardioversion and review. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(5):492–493. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(02)70005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan HL, Lie KI. Treatment of tachyarrhythmias during pregnancy and lactation. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(6):458–464. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silversides CK, Harris L, Haberer K, et al. Recurrence rates of arrhythmias during pregnancy in women with previous tachyarrhythmia and impact on fetal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(8):1206–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tromp CH, Nanne AC, Pernet PJ, et al. Electrical cardioversion during pregnancy: safe or not? Neth Heart J. 2011;19(3):134–6. PubMed PMID: 21475392. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3047673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias–executive summary. A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the European society of cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(8):1493–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robins K, Lyons G. Supraventricular tachycardia in pregnancy. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(1):140–143. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]