Abstract

The association between height and risk of hip fracture has been investigated in several studies, but the evidence is inconclusive. We therefore conducted this meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to explore whether an association exists between height and risk of hip fracture. We searched PubMed and EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for studies of height and risk of hip fracture up to February 16, 2016. The random-effects model was used to combine results from individual studies. Seven prospective cohort studies, with 7,478 incident hip fracture cases and 907,913 participants, were included for analysis. The pooled relative risk (RR) was 1.65 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.26–2.16) comparing the highest with the lowest category of height. Result from dose-response analysis suggested a linear association between height and hip fracture risk (P-nonlinearity = 0.0378). The present evidence suggests that height is positively associated with increased risk of hip fracture. Further well-designed cohort studies are needed to confirm the present findings in other ethnicities.

1. Introduction

Hip fracture is the femoral fracture that occurs between the articular of hip joint and 5 cm below the distal point of the lesser trochanter [1]. As a major part of osteoporotic fractures, hip fracture is a major cause of disability and functional impairment [2] and contributes to both morbidity and mortality in the elderly [3]. Approximately 1.66 million hip fractures occurred worldwide in 1990 and estimates suggest that this figure will rise to 4.5 million by the year 2050 [4, 5]. As the magnitude of this public health challenge is increasing, identification of risk factors for hip fracture becomes a salient public health priority and can help to better understand the pathogenesis of hip fractures.

Previous studies have shown that smoking, physical inactivity, and low body mass index were associated with increased risk of hip fracture [6–8]. Other potential risk factors like height has also been reported by several epidemiological studies. However, the relationship between height and risk of hip fracture is inconsistent. Some studies [9–15] have reported significantly increased risk among taller participants, while others [16, 17] have failed to confirm this finding. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the evidence from prospective cohort studies to explore whether an association exists between height and risk of hip fracture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted this meta-analysis according to the checklist of the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [18]. A literature search (up to February 16, 2016) of PubMed and EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for prospective cohort studies examining the association between height and risk of hip fracture was performed without language restriction. The search terms used were hip fracture and height. Pertinent studies were retrieved by further screening of the reference lists.

2.2. Study Selection

Studies were included for analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) having a prospective cohort design, (2) considering the association between height and risk of hip fracture, (3) reporting risk estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for at least three quantitative height categories (usually divided into tertile or quartile). Animal studies, reviews, conference abstracts, editorials, and letters were excluded. If a study was reported in more than one article, only the result with the longest follow-up years was used.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (W. F. and Y. C.) independently carried out the data extraction. The following data were extracted from each included study: name of the first author, publication year, study name, study location, follow-up years, characteristics of participants (sex and age), number of cases and participants, fracture ascertainment, variables adjusted for in the analysis, and the relative risks (RRs) or hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) of hip fracture and corresponding 95% CIs for all categories of height.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [19] was used to evaluate study quality. This scale awards a maximum of nine points to each study: selection of the study groups (maximum 4 points), comparability of the study populations (maximum 2 points), and ascertainment of the outcome of interest (maximum 3 points). Studies that scored 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 were considered as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To take into account heterogeneity between studies, a random-effects model [20] was used to calculate summary RRs and 95% CI for the highest versus the lowest categories of height and for the dose-response analysis. The hazard ratios (HRs) were considered equivalent to RRs. For study that reported RRs based on sex or different age groups, we pooled these RRs with inverse variance weight and used combined estimates for that study. The method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker [21] was used to compute study-specific slopes (linear trends) and 95% CIs from the natural logs of the RRs and CIs across categories of height. As this method requires that the distribution of cases and person-years or noncases and the RRs with the variance estimates for at least 3 quantitative exposure categories are known, we estimated the distribution of cases or person-years in studies that did not report these but reported the total number of cases/person-years [22].

We assigned the median or mean height in each category to the corresponding RR for each study. When the median or mean height per category was not reported, the midpoint of the upper and lower boundaries was considered the height of each category. If the lower or upper boundaries for the lowest and highest category were not available, we assumed the length of these categories to be the same as the closest category. We examined a potential nonlinear relationship between height and hip fracture risk by using restricted cubic splines with 3 knots at percentiles (10%, 50%, and 90%) of the distribution [23]. A P value for nonlinearity was calculated by testing the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the second spline was equal to zero [24].

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by using Q statistics (significance level of P≦0.10) and I 2 statistics [25]. I 2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to be low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively [26]. Subgroup analyses stratified by sex, study location, number of participants and cases, follow-up years, quality scores, and adjustment for confounders were conducted to investigate sources of heterogeneity. We also performed sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of each individual study on the pooled result. Potential publication bias was examined by Begg's funnel plots and Egger's test [27, 28]. The trim and fill method was used to further assess the possible effect of potential publication bias on the overall result [29]. This method considers the possibility of hypothetical missing studies that might exist, estimates their RRs, and recalculates a pooled RR that incorporates the estimated RRs of these hypothetical missing studies. All statistical analyses were done using Stata version 11.0. P values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless where otherwise stated.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

Figure 1 presents the results of the literature search and study selection process. The initial search yielded 2,725 records using the search strategy: of these, 473 duplicate articles were removed resulting in retaining 2,252 abstracts for further review. Further, 2,225 articles were excluded during abstract screening (173 nonhuman studies, 375 nonoriginal studies, 306 meeting abstracts, 1,292 not studying height or hip fracture, and 79 not cohort studies). After evaluating the full text of the remained 27 articles, we excluded 19 articles that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria; we further excluded 1 article [30] that reported the same cohorts with short follow-up years with another article [10]. Finally, 7 prospective cohort studies [10–16] were included for analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selection of prospective cohort studies.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. All the studies were prospective cohort studies published between 1991 and 2011, with a total of 907,913 participants with 7,478 incident hip fracture cases involved. Four studies were conducted in the US [10, 13–15]; the other 3 were conducted in Europe [11, 12, 16]. Four studies [11, 12, 15, 16] consisted of both women and men, 2 studies [10, 13] only involved women, and 1 study [14] only consisted of men. The age of participants at baseline varied from 35 to more than 85 years old. The follow-up years ranged from 7 years to 22 years. All included studies reported adjusted RR, and the potential confounding factors being adjusted for varied in different studies, including age, alcohol consumption, smoking, weight, and education. For the study quality assessment result, 2 studies [10, 15] were in moderate quality while other 5 studies [11–14, 16] were in high quality (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/2480693).

Table 1.

Characteristics of epidemiological studies of height and risk of hip fracture included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Cohort | Age (years) | Number of cases/number of participants | Follow-up years | Endpoint ascertainment | Sex | Exposure level (cm)2 | RR (95% CI) | Adjustment for confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paganini-Hill et al., 1991, US. [15] | The Leisure World Study | Median 73 | 418/13,649 | 7 | Medical records | Female | ≧165.1 versus ≦157.5 | 1.26 (0.98, 1.62) | Age |

| Male | ≧180.3 versus ≦170.2 | 1.48 (0.86, 2.55) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Meyer et al., 1993, Norway [11] | National Health Screening Service (1974–1990) | 35–49 | 210/52,313 | 10.9 | Medical records | Female | ≧170 versus <155 | 3.62 (1.46, 8.97) | Age |

| Male | ≧185 versus <170 | 2.92 (0.94, 9.05) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Meyer et al., 1995, Norway [12] | National Health Screening Service (1963–1975) | 50–89 | 6,087/673,848 | 16.4 | Death certificates | Female | A1: >165 versus ≦157 | 1.26 (0.74, 1.68) | Age |

| A2: >163 versus ≦156 | 1.10 (0.96, 1.26) | ||||||||

| A3: >161 versus ≦154 | 1.19 (1.04, 1.35) | ||||||||

| A4: >160 versus ≦153 | 1.07 (0.81, 1.41) | ||||||||

| Male | A1: >178 versus ≦170 | 0.98 (0.68, 1.42) | |||||||

| A2: >176 versus ≦168 | 1.20 (0.98, 1.45) | ||||||||

| A3: >175 versus ≦167 | 1.10 (0.90, 1.33) | ||||||||

| A4: >174 versus ≦165 | 1.00 (0.67, 1.51) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Hemenway et al., 1995, US. [10] | Nurses Health Study | 35–59 | 243/92,804 | 10 | Self-report, confirmed by medical records | Female | ≧172.7 versus 157.5 | 2.40 (1.43, 4.02) | Age, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption |

|

| |||||||||

| Owusu et al., 1998, US. [14] | Health Professionals Follow-Up Study | 40–75 | 56/43,053 | 8 | Self-report | Male | ≧188 versus ≦168 | 3.97 (1.28, 12.3) | Age, weight, calcium intake, smoking, alcohol consumption, waist-to-hip ratio |

|

| |||||||||

| Opotowsky et al., 2003, US. [13] | NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study | 40–74 | 203/4,264 | 22 | Medical records | Female | B1: ≧168.3 versus ≦155.2 | 3.91 (1.37, 11.13) | Age, weight, age at menopause, hormone use, recreational activity, nonrecreational activity, alcohol use, history of fracture, history of chronic diseases |

| B2: ≧165.4 versus ≦152.0 | 2.01 (1.18, 3.44) | ||||||||

| B3: ≧165.4 versus ≦152.1 | 1.27 (0.70, 2.29) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Benetou et al., 2011, 5 European countries1 [16] | EPIC-Elderly-NAH Study | 60–86 | 261/27,982 | 8 | Self-report or medical records | Female/male | ≧180 versus ≦149 | 1.59 (0.60, 4.22) | Age, educational level, smoking status, history of diabetes mellitus |

1Including Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, and Sweden.

2A1: 50–59 years; A2: 60–69 years; A3: 70–79 years; A4: 80–89 years; B1: 40–59 years; B2: 60–69 years; B3: 70–74 years.

3.3. Tall versus Short

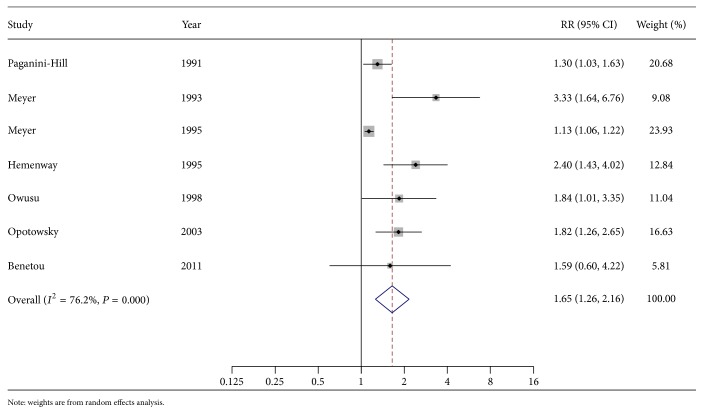

Figure 2 shows a forest plot presenting the association between height and risk of hip fracture. The summary RR of hip fracture for the highest versus lowest category in height was 1.65 (95% CI: 1.26 to 2.16). Statistically significant heterogeneity was observed among the individual results (I 2 = 76.2%, P-heterogeneity < 0.05).

Figure 2.

A forest plot of the association between height and risk of hip fracture.

3.4. Dose-Response Meta-Analysis

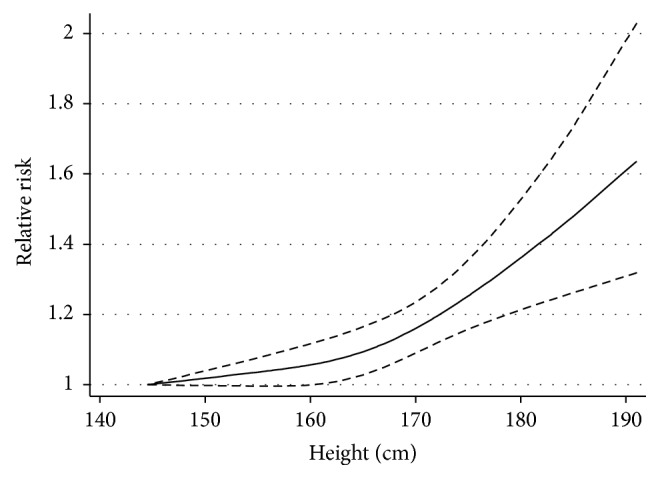

Figure 3 presents the dose-response relations between height and relative risks of hip fracture. There was evidence of a nonlinear association between height and hip fracture risk (P-nonlinearity = 0.0378). As compared with individuals who were in the lowest height, the RR of hip fracture for each 10 cm increment was 1.007 (95% CI: 1.002–1.012).

Figure 3.

Dose-response relations between height and relative risk of hip fracture. The solid line and the long dashed lines represent the estimated relative risk and corresponding 95% CI, respectively. There was evidence of a nonlinear association between height and hip fracture risk (P-nonlinearity = 0.0378).

3.5. Publication Bias

Publication bias was found across the included studies indicated by Begg's and Egger's test (both P values < 0.05). However, the trim and fill method identified 3 hypothetical missing studies, and the repooled results incorporating the hypothetical studies continued to show a statistically significant association between height and risk of hip fracture (RR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.06–1.71).

3.6. Subgroup Analysis and Sensitivity Analysis

Table 2 summaries the results of subgroup analysis according to study characteristics. The associations between height and hip fracture risk were similar in subgroup analyses stratified by sex, study location, number of participants or cases, follow-up years, quality scores, and adjustment for confounders. Sensitivity analysis showed that the summary RR was not substantially influenced by any of the individual study, with a range from 1.50 (95% CI: 1.18–1.92) when omitting Meyer et al.'s (1993) study [11] to 1.83 (95% CI: 1.38–2.44) when excluding Meyer et al.'s (1995) study [12].

Table 2.

Summary of the results on association between height and risk of hip fracture.

| Variables | Number of studies | RR (95% CI) | I 2% | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 7 | 1.65 (1.26, 2.16) | 76.2 | 0.000 |

| Location | ||||

| US | 4 | 1.69 (1.27, 2.24) | 50.3 | 0.110 |

| Europe | 3 | 1.72 (0.83, 3.58) | 78.5 | 0.000 |

| Follow-up years | ||||

| <10 | 3 | 1.37 (1.11, 1.69) | 0.0 | 0.543 |

| ≧10 | 4 | 1.88 (1.15, 3.07) | 86.5 | 0.000 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 5 | 1.60 (1.18, 2.16) | 78.8 | 0.000 |

| Male | 4 | 1.42 (1.00, 2.02) | 50.9 | 0.106 |

| Both sex | 1 | 1.59 (0.60, 4.22) | NA | NA |

| Number of participants | ||||

| <50000 | 4 | 1.47 (1.22, 1.76) | 0.0 | 0.402 |

| ≧50000 | 3 | 1.96 (0.96, 4.01) | 88.0 | 0.000 |

| Number of cases | ||||

| <400 | 5 | 2.07 (1.62, 2.64) | 0.0 | 0.569 |

| ≧400 | 2 | 1.16 (1.04, 1.29) | 23.6 | 0.252 |

| Study quality | ||||

| Moderate | 2 | 1.69 (0.93, 3.06) | 77.9 | 0.034 |

| High | 5 | 1.71 (1.14, 2.56) | 76.9 | 0.000 |

| Adjustment for confounders | ||||

| Number of confounders | ||||

| <4 | 3 | 1.39 (1.01, 1.91) | 80.0 | 0.007 |

| ≧4 | 4 | 1.94 (1.49, 2.51) | 0.0 | 0.812 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 1.97 (1.50, 2.57) | 0.0 | 0.675 |

| No | 4 | 1.39 (1.04, 1.86) | 71.1 | 0.016 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 2.06 (1.43, 2.96) | 0.0 | 0.690 |

| No | 4 | 1.49 (1.11, 2.01) | 80.7 | 0.001 |

| Weight | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 1.83 (1.33, 2.50) | 0.0 | 0.976 |

| No | 5 | 1.58 (1.15, 2.17) | 77.7 | 0.001 |

4. Discussion

Based on the meta-analysis of 907,913 participants from prospective cohort studies, the present study found a positive association between height and increased risk of hip fracture. A nonlinear association between height and the risk of hip fracture was observed in the dose-response analysis.

Several plausible mechanisms exist for the association between height and risk of hip fracture. First, the center of gravity of taller people was higher than that of shorter people; thus taller people have further probability to fall and may hit the ground with more energy when falling [13]. Second, hip axis length, which refers to the distance from the lower base of the greater trochanter to inner pelvic brim [31], is suggested to be positively associated with increased risk of hip fracture, even after controlling for age, weight, and BMD [31, 32]. However, it has been shown that height and hip axis length are highly correlated, with an estimated correlation coefficient as high as more than 0.5 in different ethnic groups [33]. This implies that taller people might have higher risk of hip fracture due to the longer hip axis length. Third, growth is determined by both genetic and environmental factors, such as dietary intake, living conditions, and physical activities [34]. However, the environmental factors that related to height may act synchronously to the increased risk of hip fracture.

Hip fracture affects both men and women. In our study, a greater summary HR of hip fracture was observed in women (HR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.18–2.16) than in men (HR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.00–2.02). However, because the CIs for HR of hip fracture are overlapping for women and men, and meanwhile the lower limit of the CI for men includes 1, whether there is a gender difference of association between body height and risk of hip fracture should be further explored.

Due to the aging of the population, the number of hip fractures continues to increase [35, 36]. Although it is possible for most patients to return to their function level before the fracture with surgery followed by early mobilization, the treatment costs may result in increased risk of morbidity and mortality for some patients [37]. It is therefore imperative that we identify risk factors for hip fracture, with the goal of directing primary prevention. Unlike diet and behavior factors, height is a nonmodifiable characteristic. Nevertheless, the findings of our study have significance for the identification of high-risk population.

Our meta-analysis had several strengths. Because this meta-analysis only included prospective cohort studies, we minimized the potential effect of recall bias on our findings. In addition, each included study had a follow-up period long enough to observe potential association between height and risk of hip fracture. Another strength was that the studies involved a large number of participants; it was therefore possible to detect moderate reductions in risk.

Our study also had some limitations that deserve consideration. First, because our meta-analysis was based on observational studies, we could not rule out potential confounding from other fracture risk factors. Although the included studies adjusted for several potential confounders, for example, all studies adjusted for age, three studies adjusted for alcohol intake, and three studies adjusted for smoking, the association between height and risk of hip fracture could potentially be due to residual confounding from other factors related to tall people.

Second, although it has been shown that self-report was relatively accurate for hip fracture in adults [38, 39], however, there might be also misclassification of height and hip fracture due to less valid self-reported height in the elderly. Underestimation of height might be related to the height loss in old people who reported their height as measured in early adulthood without being aware of changes in their stature [40].

Third, the potential publication bias existed across the included studies indicated that studies reporting positive association between height and risk of hip fracture were more easily published, as indicated by Egger's test and Begg's test. However, when we performed the trim and fill method, the result continued to suggest statistically significant association between height and hip fracture, although the pooled RR was attenuated by the hypothesized missing studies.

Fourth, high statistical heterogeneity was found across the studies. One potential source of heterogeneity might be the difference of the number of hip fracture cases between studies, as suggested by the subgroup analysis. Although the heterogeneity may weaken the strength of our findings, the subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis showed that results from our meta-analysis were robust.

Finally, the results of our meta-analysis were based on studies that only involved participants from Europe or the United States. However, the genetic factors and environmental factors with respect to height varied among different ethnicities, especially between east and west. Therefore, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution among the population from the east.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the results from this meta-analysis of prospective studies indicate that height is positively associated with risk of hip fracture. However, due to residual confounding from other fracture risk factors related to height, the findings from this meta-analysis need to be confirmed by well-designed prospective studies, especially among other ethnicities.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 presented the methodological quality score of included studies assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Studies that scored 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 were considered as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively. 5 studies were in high quality while the other 2 studies were in moderate quality.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81401834), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (no. 2014CFB363), and Health and Family Planning Commission Program of Wuhan City (no. WX14B18).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions

Danmou Xing conceived and designed the experiments; Zhihong Xiao, Dong Ren, Wei Feng, and Yan Chen analyzed the data; Wei Feng, Yan Chen, and Wusheng Kan contributed with reagents/materials/analysis tools; Zhihong Xiao, Dong Ren, and Danmou Xing wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Abrahamsen B., van Staa T., Ariely R., Olson M., Cooper C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporosis International. 2009;20(10):1633–1650. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0920-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannus P., Parkkari J., Niemi S., et al. Prevention of hip fracture in elderly people with use of a hip protector. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(21):1506–1513. doi: 10.1056/nejm200011233432101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhanwal D. K., Dennison E. M., Harvey N. C., Cooper C. Epidemiology of hip fracture: worldwide geographic variation. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2011;45(1):15–22. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.73656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper C., Campion G., Melton L. J., III Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporosis International. 1992;2(6):285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF01623184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gullberg B., Johnell O., Kanis J. A. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporosis International. 1997;7(5):407–413. doi: 10.1007/PL00004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson H., Kanis J. A., Odén A., et al. A meta-analysis of the association of fracture risk and body mass index in women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2014;29(1):223–233. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law M. R., Hackshaw A. K. A meta-analysis of cigarette smoking, bone mineral density and risk of hip fracture: recognition of a major effect. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7112):841–846. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7112.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu X., Zhang X., Zhai Z., et al. Association between physical activity and risk of fracture. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2014;29(1):202–211. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunnes M., Lehmann E. H., Mellstrom D., Johnell O. The relationship between anthropometric measurements and fractures in women. Bone. 1996;19(4):407–413. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(96)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemenway D., Feskanich D., Colditz G. A. Body height and hip fracture: a cohort study of 90,000 women. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;24(4):783–786. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer H. E., Tverdal A., Falch J. A. Risk factors for hip fracture in middle-aged Norwegian women and men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1993;137(11):1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer H. E., Tverdal A., Falch J. A. Body height, body mass index, and fatal hip fractures: 16 years' follow-up of 674,000 norwegian women and men. Epidemiology. 1995;6(3):299–305. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199505000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opotowsky A. R., Su B. W., Bilezikian J. P. Height and lower extremity length as predictors of hip fracture: results of the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2003;18(9):1674–1681. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owusu W., Willett W., Ascherio A., et al. Body anthropometry and the risk of hip and wrist fractures in men: results from a prospective study. Obesity Research. 1998;6(1):12–19. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paganini-Hill A., Chao A., Ross R. K., Henderson B. E. Exercise and other factors in the prevention of hip fracture: the Leisure World study. Epidemiology. 1991;2(1):16–25. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benetou V., Orfanos P., Benetos I. S., et al. Anthropometry, physical activity and hip fractures in the elderly. Injury. 2011;42(2):188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanis J., Johnell O., Gullberg B., et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in men from southern europe: the MEDOS study. Osteoporosis International. 1999;9(1):45–54. doi: 10.1007/s001980050115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stroup D. F., Berlin J. A., Morton S. C., et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells G., Shea B., O'connell D., et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

- 20.Berkey C. S., Hoaglin D. C., Mosteller F., Colditz G. A. A random-effects regression model for meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14(4):395–411. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenland S., Longnecker M. P. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;135(11):1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aune D., Greenwood D. C., Chan D. S. M., et al. Body mass index, abdominal fatness and pancreatic cancer risk: a systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(4):843–852. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orsini N., Li R., Wolk A., Khudyakov P., Spiegelman D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose-response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;175(1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harre F. E., Jr., Lee K. L., Pollock B. G. Regression models in clinical studies: determining relationships between predictors and response. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1988;80(15):1198–1202. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.15.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begg C. B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M., Smith G. D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemenway D., Azrael D. R., Rimm E. B., Feskanich D., Willett W. C. Risk factors for hip fracture in US men aged 40 through 75 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(11):1843–1845. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.11.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frisoli A., Jr., Paula A. P., Pinheiro M., et al. Hip axis length as an independent risk factor for hip fracture independently of femural bone mineral density in Caucasian elderly Brazilian women. Bone. 2005;37(6):871–875. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faulkner K. G., Cummings S. R., Black D., Palermo L., Glüer C.-C., Genant H. K. Simple measurement of femoral geometry predicts hip fracture: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1993;8(10):1211–1217. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greendale G. A., Young J. T., Huang M.-H., Bucur A., Wang Y., Seeman T. Hip axis length in mid-life Japanese and Caucasian U.S. residents: no evidence for an ethnic difference. Osteoporosis International. 2003;14(4):320–325. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1367-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee E. M., Park M. J., Ahn H. S., Lee S. M. Differences in dietary intakes between normal and short stature Korean children visiting a growth clinic. Clinical Nutrition Research. 2012;1(1):23–29. doi: 10.7762/cnr.2012.1.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia W.-B., He S.-L., Xu L., et al. Rapidly increasing rates of hip fracture in Beijing, China. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(1):125–129. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens J. A., Rudd R. A. The impact of decreasing U.S. hip fracture rates on future hip fracture estimates. Osteoporosis International. 2013;24(10):2725–2728. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2375-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuckerman J. D. Hip fracture. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(23):1519–1525. doi: 10.1056/nejm199606063342307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivers R. Q., Cumming R. G., Mitchell P., Peduto A. J. The accuracy of self-reported fractures in older people. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55(5):452–457. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Z., Kooperberg C., Pettinger M. B., et al. Validity of self-report for fractures among a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative observational study and clinical trials. Menopause. 2004;11(3):264–274. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000094210.15096.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahl A. K., Hassing L. B., Fransson E. I., Pedersen N. L. Agreement between self-reported and measured height, weight and body mass index in old age—a longitudinal study with 20 years of follow-up. Age and Ageing. 2010;39(4):445–451. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 presented the methodological quality score of included studies assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Studies that scored 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 were considered as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively. 5 studies were in high quality while the other 2 studies were in moderate quality.