Abstract

Objective. Esophageal carcinoma (EC) is a frequently common malignancy of gastrointestinal cancer in the world. This study aims to screen key genes and pathways in EC and elucidate the mechanism of it. Methods. 5 microarray datasets of EC were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened by bioinformatics analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment, and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction were performed to obtain the biological roles of DEGs in EC. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to verify the expression level of DEGs in EC. Results. A total of 1955 genes were filtered as DEGs in EC. The upregulated genes were significantly enriched in cell cycle and the downregulated genes significantly enriched in Endocytosis. PPI network displayed CDK4 and CCT3 were hub proteins in the network. The expression level of 8 dysregulated DEGs including CDK4, CCT3, THSD4, SIM2, MYBL2, CENPF, CDCA3, and CDKN3 was validated in EC compared to adjacent nontumor tissues and the results were matched with the microarray analysis. Conclusion. The significantly DEGs including CDK4, CCT3, THSD4, and SIM2 may play key roles in tumorigenesis and development of EC involved in cell cycle and Endocytosis.

1. Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma (EC) is the sixth leading cause of cancer mortality in males and the ninth leading cause of cancer mortality in females in 2012 worldwide [1]. The highest incident rates of EC are found in Eastern Asia, Southern Africa, and Eastern Africa and the lowest incidence rate of EC is found in Western Africa [1]. Esophageal carcinoma is usually 3 to 4 times more common among men than women. The 5-year overall survival ranges from 15% to 25% [2]. In China, it is predicted that EC is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in males and females after lung and bronchus, stomach, and liver in 2015 [3].

EC is classified as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) according to histological type and ESCC is the predominant histological type of EC in the world [2]. It is reported that tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, and low intake of fruits and vegetables are major risk factors for ESCC [4]. Overweight, obesity, gastroesophagus reflux disease (GERD), and Barrett's esophagus increase incidence risk of EAC [1, 5].

In addition to the above-mentioned environmental factors, abnormal expression of miRNA and genes and methylation of genes and SNPs are associated with EC tumorigenesis and development. miR-219-1 rs107822G > A polymorphism might significantly decrease ESCC risk through changing individual susceptibility to Chinese Kazakhs [5]. The cases carrying the GG variant homozygote have a significant 2.81-fold increased risk of EC [6]. miR-330-3p promotes cell growth, cell migration, and invasion and inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis in ESCC cells via suppression of PDCD4 expression [7]. miR-199a-5p downregulation contributes to enhancing EC cell proliferation through upregulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase-11 [8]. DACT2 is frequently methylated in human esophageal cancer; methylated DATC2 accelerates esophageal cancer development by activating Wnt signaling [9]. RUNX3 methylation is associated with an increased risk, progression, and poor survival in EC [10].

Currently, the molecular mechanism of EC was unclear. In this study, we used bioinformatics methods to analyze the mRNA expression data of EC, which were available on the GEO database, to identify key genes and pathways in EC, aiming to provide valuable information for further pathogenesis mechanism elucidation and provide ground work for therapeutic targets identification for EC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Expression Profile Microarray

Gene expression profiles data were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The datasets of patients receiving preoperative treatment before oesophagectomy and cell lines receiving drug stimulus were excluded. Total of 5 mRNA expression datasets of EC tissues/cell lines comprising GSE53625, GSE33810, GSE17351, GSE9982, and GSE12737 were included in our study.

2.2. Identification of DEGs

The raw data of the mRNA expression profiles were downloaded and analyzed by R language software [11]. Background correction, quartile data normalization, and probe summarization were applied for the original data. The limma [12] method in Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/) was used to identify genes which were differentially expressed between EC and normal controls; the significance of DEGs was calculated by t-test and was represented by p value. To reduce the risk of false positives, p values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) method. The corrected p value was represented by FDR [13]. FDR < 0.05 were considered as the cutoff values for DEG screening.

2.3. Gene Ontology Analysis

GO is a useful tool for collecting a large number of gene annotation terms [14]. The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) [15], is bioinformatics resources consisting of an integrated biological knowledgebase and analytic tools aimed at systematically extracting biological functional annotation from large gene/protein lists, such as being derived from high-throughput genomic experiments. To gain the in-depth understanding of the biological functions of DEGs, DAVID tool was used to obtain the enriched GO terms of DEGs based on the hypergeometric distribution to compute p values, which were corrected by the Benjamini and Hochberg FDR method for multiple hypothesis testing. FDR < 0.05 was set as the threshold value.

2.4. KEGG Enrichment Pathways

KEGG is a database resource for understanding functions of genes list from molecular level [16]. GeneCoDis3 is a valuable tool to functionally interpret results from experimental techniques in genomics [17]. This web-based application integrates different sources of information for finding groups of genes with similar biological meaning. The enrichment analysis of GeneCoDis3 is essential in the interpretation of high-throughput experiments. In the study, GeneCoDis3 software was used to test the statistical enrichment of DEGs in KEGG pathways. p < 0.05 was set as the threshold value.

2.5. PPI Interaction Network

The Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID: http://thebiogrid.org/) is an open access archive of genetic and protein interactions that are curated from the primary biomedical literature for all major model organism species including budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. In a word, BioGRID is a depository for genetic and protein interactions based on experimental verification [18]. The top 10 upregulated genes and top 10 downregulated genes between EC and normal controls were subjected to BioGRID database to get the predicted PPIs of these DEGs. The PPIs were visualized in Cytoscape [17].

2.6. qRT-PCR Validation

Total RNA of fresh paired EC tumor and adjacent nontumor specimens were extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The SuperScript III Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA) was used to synthesize the cDNA. qRT-PCR reactions were performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on the Applied Biosystems 7500 (Foster City, CA, USA). β-actin was used as internal control for mRNA detected. The relative expression of genes was calculated using the comparative Ct methods [19]. The PCR primers were used as shown in supplementary Table S3 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/2968106.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of DEGs

Five mRNA expression profiles including 208 EC samples and 195 normal controls were downloaded and analyzed, as shown in Table 1. 208 EC samples comprised 207 squamous cell carcinoma samples and 1 adenocarcinoma sample. 1955 DEGs were identified in EC compared to normal control, including 919 upregulated and 1036 downregulated genes. The top 10 significantly upregulated and downregulated genes were listed in Table 2. The most significantly up- and downregulated genes were CDK4 and THSD4, respectively. The full list of DEGs in EC was shown in supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

The information of gene expression microarrays of EC.

| GEO ID | Platform | Case : control | Sample type | Country | Time | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE53625 | GPL18109 CBC Homo sapiens lncRNA + mRNA microarray V2.0 | 179 : 179 | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | China | 2014 | Li et al. [42] |

| GSE33810 | GPL570 [HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | 2 : 1 | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | HK | 2013 | Chen et al. [43] |

| GSE17351 | GPL570 [HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array | 5 : 5 | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | USA | 2009 | Long et al. [44] |

| GSE9982 | GPL1928 CodeLink Human 20K ver4.1 | 20 : 2 | Esophageal squamous cancer | Japan | 2006 | Shimokuni et al. [45] |

| GSE12737 | GPL7262 Human ORESTES NoMatch 4.8k v1.0 | 2 : 8 | Squamous cell & adenocarcinoma | Brazil | 2009 | Mello et al. [46] |

EC: esophageal carcinoma.

Table 2.

The top 10 up-regulated and top 10 down-regulated DEGs in EC.

| Gene ID | Gene symbol | Official full name | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated (top 10) | |||

| 1019 | CDK4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | 0.0002252 |

| 4605 | MYBL2 | MYB protooncogene like 2 | 0.0002252 |

| 7203 | CCT3 | Chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 3 | 0.0003378 |

| 83461 | CDCA3 | Cell division cycle associated 3 | 0.0004504 |

| 1033 | CDKN3 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 | 0.0004504 |

| 1063 | CENPF | Centromere protein F | 0.0004729 |

| 9156 | EXO1 | Exonuclease 1 | 0.0004729 |

| 79075 | DSCC1 | DNA replication and sister chromatid cohesion 1 | 0.0005405 |

| 4751 | NEK2 | NIMA related kinase 2 | 0.0005405 |

| Downregulated (top 10) | |||

| 79875 | THSD4 | Thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 4 | 0.0002252 |

| 79026 | AHNAK | AHNAK nucleoprotein | 0.0004729 |

| 6493 | SIM2 | Single-minded family bHLH transcription factor 2 | 0.0004729 |

| 7881 | KCNAB1 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member regulatory beta subunit 1 | 0.0005405 |

| 90865 | IL33 | Interleukin 33 | 0.0008812 |

| 55287 | TMEM40 | Transmembrane protein 40 | 0.0008812 |

| 966 | CD59 | CD59 molecule | 0.0015608 |

| 5121 | PCP4 | Purkinje cell protein 4 | 0.0015608 |

| 22885 | ABLIM3 | Actin binding LIM protein family member 3 | 0.0016629 |

| 3590 | IL11RA | Interleukin 11 receptor subunit alpha | 0.0016629 |

EC: esophageal carcinoma; FDR: false discovery rate.

3.2. GO Analysis of DEGs

Following GO analyses for up- and downregulated DEGs, significant GO terms including biological process, cellular component, and molecular function were collected. For upregulated DEGs, cell cycle was the most significant enrichment of biological process; membrane-enclosed lumen was the highest enrichment of cellular component; nucleotide binding was the highest enrichment of molecular function, as shown in Table 3. For downregulated DEGs, response to wounding was the most significant enrichment of biological process; actin cytoskeleton was the highest enrichment of cellular component and cytoskeletal protein binding was the highest enrichment of molecular function, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

GO annotation of upregulated DEGs in EC.

| GO ID | GO term | Count | p-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological process | ||||

| GO:0007049 | Cell cycle | 152 | 4.10E − 13 | 7.59E − 10 |

| GO:0022402 | Cell cycle process | 118 | 3.44E − 12 | 6.36E − 09 |

| GO:0022403 | Cell cycle phase | 90 | 2.00E − 10 | 3.71E − 07 |

| GO:0000278 | Mitotic cell cycle | 82 | 5.34E − 10 | 9.87E − 07 |

| GO:0051301 | Cell division | 67 | 8.80E − 09 | 1.63E − 05 |

| GO:0000279 | M phase | 70 | 6.27E − 08 | 1.16E − 04 |

| GO:0000087 | M phase of mitotic cell cycle | 49 | 3.38E − 06 | 0.0062547 |

| GO:0000280 | Nuclear division | 48 | 4.65E − 06 | 0.0086014 |

| GO:0007067 | Mitosis | 48 | 4.65E − 06 | 0.0086014 |

| GO:0048285 | Organelle fission | 49 | 6.41E − 06 | 0.011854 |

| GO:0033554 | Cellular response to stress | 95 | 2.02E − 05 | 0.0373322 |

| Cellular component | ||||

| GO:0031974 | Membrane-enclosed lumen | 276 | 1.12E − 10 | 1.65E − 07 |

| GO:0043233 | Organelle lumen | 270 | 2.41E − 10 | 3.56E − 07 |

| GO:0043232 | Intracellular non-membrane-bounded organelle | 359 | 8.74E − 10 | 1.29E − 06 |

| GO:0043228 | Non-membrane-bounded organelle | 359 | 8.74E − 10 | 1.29E − 06 |

| GO:0070013 | Intracellular organelle lumen | 259 | 4.54E − 09 | 6.71E − 06 |

| GO:0031981 | Nuclear lumen | 216 | 1.90E − 08 | 2.80E − 05 |

| GO:0000775 | Chromosome, centromeric region | 36 | 2.52E − 08 | 3.72E − 05 |

| GO:0005829 | Cytosol | 192 | 1.36E − 06 | 0.0020016 |

| GO:0015630 | Microtubule cytoskeleton | 92 | 4.62E − 06 | 0.0068255 |

| GO:0000793 | Condensed chromosome | 32 | 6.75E − 06 | 0.009972 |

| GO:0000779 | Condensed chromosome, centromeric region | 21 | 7.55E − 06 | 0.011151 |

| GO:0044427 | Chromosomal part | 69 | 9.92E − 06 | 0.0146408 |

| GO:0005635 | Nuclear envelope | 43 | 1.37E − 05 | 0.0202598 |

| GO:0000777 | Condensed chromosome kinetochore | 19 | 1.48E − 05 | 0.0219025 |

| GO:0005694 | Chromosome | 78 | 1.75E − 05 | 0.02589 |

| GO:0000776 | Kinetochore | 22 | 2.72E − 05 | 0.0401619 |

| Molecular function | ||||

| GO:0000166 | Nucleotide binding | 305 | 5.53E − 06 | 0.0090275 |

| GO:0017076 | Purine nucleotide binding | 266 | 5.55E − 06 | 0.0090714 |

| GO:0030554 | Adenyl nucleotide binding | 223 | 1.07E − 05 | 0.0175078 |

| GO:0001883 | Purine nucleoside binding | 225 | 1.49E − 05 | 0.0242774 |

| GO:0032555 | Purine ribonucleotide binding | 252 | 2.35E − 05 | 0.0383944 |

| GO:0032553 | Ribonucleotide binding | 252 | 2.35E − 05 | 0.0383944 |

| GO:0001882 | Nucleoside binding | 225 | 2.44E − 05 | 0.0398342 |

EC: esophageal carcinoma; FDR: false discovery rate.

Table 4.

GO annotation of downregulated DEGs in EC.

| GO ID | GO term | Count | p value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological process | ||||

| GO:0009611 | Response to wounding | 65 | 1.98E − 08 | 3.57E − 05 |

| GO:0042060 | Wound healing | 33 | 5.75E − 08 | 1.04E − 04 |

| GO:0030097 | Hemopoiesis | 32 | 1.85E − 05 | 0.0334238 |

| GO:0007167 | Enzyme linked receptor protein signaling pathway | 41 | 2.03E − 05 | 0.0365533 |

| GO:0030036 | Actin cytoskeleton organization | 31 | 2.05E − 05 | 0.0370181 |

| GO:0048534 | Hemopoietic or lymphoid organ development | 34 | 2.06E − 05 | 0.0372021 |

| GO:0007155 | Cell adhesion | 69 | 2.10E − 05 | 0.0378896 |

| GO:0042692 | Muscle cell differentiation | 21 | 2.14E − 05 | 0.0386651 |

| GO:0022610 | Biological adhesion | 69 | 2.19E − 05 | 0.0394751 |

| GO:0007178 | Transmembrane receptor protein serine/threonine kinase signaling pathway | 19 | 2.53E − 05 | 0.0456886 |

| Cellular component | ||||

| GO:0015629 | Actin cytoskeleton | 36 | 5.84E − 06 | 0.008305 |

| GO:0005794 | Golgi apparatus | 83 | 7.36E − 06 | 0.0104637 |

| GO:0005856 | Cytoskeleton | 118 | 1.23E − 05 | 0.0175254 |

| Molecular function | ||||

| GO:0008092 | Cytoskeletal protein binding | 59 | 8.55E − 07 | 0.0013403 |

EC: esophageal carcinoma; FDR: false discovery rate.

3.3. KEGG Enrichment Pathways of DEGs

Following KEGG enrichment analysis for DEGs, significant KEGG terms were collected. The pathways enriched by 919 upregulated DEGs were mainly related to cell cycle, RNA transport, and p53 signaling pathway (Table 5). 1036 downregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in Endocytosis, focal adhesion, and vascular smooth muscle contraction, as shown in Table 6.

Table 5.

The KEGG pathway enrichment of up-regulated DEGs in EC.

| KEGG ID | KEGG terms | Count | FDR | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04110 | Cell cycle | 19 | 7.86E − 08 | CDK6, CCNE2, CCNB2, FZR1, CCNA2, CDC7, YWHAQ, MCM7, CCNE1, CDK4, E2F5, CCNB1, MAD2L1, CDC25B, MCM6, BUB1, RBL1, MCM2, CDK1 |

| hsa03013 | RNA transport | 20 | 1.09E − 07 | RAN, EIF3H, NUP43, UBE2I, NUP133, MAGOHB, POP5, THOC5, CLNS1A, NUP205, GEMIN6, NUP93, NUP62, SUMO1, EIF2S2, NUP153, RANGAP1, NUP160, RPP25, DDX20 |

| hsa04115 | p53 signaling pathway | 5 | 2.90E − 06 | CCNE2, CCNB2, CCNE1, CCNB1, CDK1 |

| hsa04914 | Progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation | 8 | 1.42E − 05 | CCNB2, FZR1, CCNA2, CCNB1, MAD2L1, CDC25B, BUB1, CDK1 |

| hsa03050 | Proteasome | 9 | 1.56E − 05 | PSMD7, SHFM1, PSMD3, PSMA5, PSMB1, PSMB3, PSMA3, PSMD4, PSMA7 |

| hsa03040 | Spliceosome | 15 | 1.66E − 05 | SNRPC, SRSF9, XAB2, MAGOHB, NAA38, BUD31, SNRPF, NHP2L1, SRSF3, PQBP1, USP39, SNRNP40, SNRPD1, SNRPD2, SF3B2 |

| hsa03030 | DNA replication | 8 | 4.24E − 05 | RNASEH2A, RNASEH1, MCM7, POLE2, MCM6, RNASEH2C, MCM2, RFC4 |

| hsa03008 | Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes | 11 | 4.37E − 05 | UTP18, RAN, UTP15, NOP56, DKC1, POP5, FBL, NHP2L1, TCOF1, GNL3L, RPP25 |

| hsa03440 | Homologous recombination | 7 | 4.37E − 05 | SHFM1, MRE11A, RAD54B, XRCC2, RAD54L, BLM, TOP3A |

| hsa04114 | Oocyte meiosis | 8 | 8.96E − 05 | CCNE2, CCNB2, YWHAQ, CCNE1, CCNB1, MAD2L1, BUB1, CDK1 |

| hsa05162 | Measles | 4 | 0.0001531 | CDK6, CCNE2, CCNE1, CDK4 |

| hsa05222 | Small cell lung cancer | 4 | 0.0001531 | CDK6, CCNE2, CCNE1, CDK4 |

| hsa05200 | Pathways in cancer | 23 | 0.0001815 | VEGFB, CDK6, MTOR, FH, CCNE2, LEF1, BIRC5, CCNE1, CDK4, TCEB1, MSH6, EGF, FZD2, TFG, CKS1B, TRAF4, HSP90AA1, TRAF3, PPARG, HSP90AB1, FGF12, PIAS4, STK4 |

| hsa00510 | N-Glycan biosynthesis | 8 | 0.000312 | RFT1, ALG10, RPN2, ALG10B, ALG1, MOGS, ALG5, B4GALT2 |

EC: esophageal carcinoma; FDR: false discovery rate.

Table 6.

The KEGG pathway enrichment of downregulated DEGs in EC.

| KEGG ID | KEGG terms | Count | FDR | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04144 | Endocytosis | 23 | 5.22E − 06 | STAMBP, RAB11FIP5, SH3KBP1, KIT, FOLR2, F2R, TGFBR2, VPS4B, SH3GLB1, CHMP5, CXCR2, PDGFRA, CLTB, FOLR1, STAM2, ARAP2, DAB2, EEA1, PDCD6IP, RAB11FIP2, CBL, EPN3, VPS37B |

| hsa04510 | Focal adhesion | 19 | 0.000354 | ITGA1, ZYX, LAMB2, MYLK, IGF1, CCND2, ITGA2, RAP1A, PDGFRA, ITGA5, TNXB, VWF, PIK3R1, JUN, COL6A2, BCL2, ROCK1, MYL12A, THBS3 |

| hsa04270 | Vascular smooth muscle contraction | 14 | 0.000383 | JMJD7-PLA2G4B, MYLK, ADCY9, GNA13, PRKG1, ITPR2, PPP1R12B, GNAQ, MYH11, ACTG2, ROCK1, PLA2G2A, MRVI1, ITPR1 |

| hsa00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 4 | 0.000425 | ALDH7A1, MAOB, GATM, MAOA |

| hsa04360 | Axon guidance | 15 | 0.000456 | EPHA1, ROBO1, SEMA4B, DPYSL2, ABLIM3, PPP3CC, NCK2, GNAI2, SEMA3F, PPP3CA, RGS3, NTN1, ROCK1, PPP3CB, EFNB2 |

| hsa04020 | Calcium signaling pathway | 5 | 0.00046 | PPP3CC, ITPR2, PPP3CA, PPP3CB, ITPR1 |

| hsa04662 | B cell receptor signaling pathway | 4 | 0.000508 | PPP3CC, JUN, PPP3CA, PPP3CB |

| hsa05014 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 3 | 0.000583 | PPP3CC, PPP3CA, PPP3CB |

| hsa00340 | Histidine metabolism | 3 | 0.000583 | ALDH7A1, MAOB, MAOA |

| hsa04720 | Long-term potentiation | 6 | 0.000623 | PPP3CC, ITPR2, GNAQ, PPP3CA, PPP3CB, ITPR1 |

| hsa04114 | Oocyte meiosis | 6 | 0.00068 | ADCY9, PPP3CC, ITPR2, PPP3CA, PPP3CB, ITPR1 |

| hsa04730 | Long-term depression | 10 | 0.000701 | JMJD7-PLA2G4B, IGF1, GNA13, PRKG1, ITPR2, PPP2CB, GNAQ, GNAI2, PLA2G2A, ITPR1 |

| hsa04141 | Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 16 | 0.000709 | SEC63, UBE2J1, EIF2AK3, ATF6, CRYAB, UBE2D3, DNAJB2, SEC31B, MAN1A1, ERO1L, BCL2, HERPUD1, DNAJC3, UBQLN2, RAD23B, LMAN1 |

| hsa04912 | GnRH signaling pathway | 12 | 0.000736 | JMJD7-PLA2G4B, MMP2, ADCY9, MAP3K3, HBEGF, ITPR2, MAPK7, GNAQ, MAP3K4, JUN, PLA2G2A, ITPR1 |

| hsa00280 | Valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation | 8 | 0.000738 | ALDH7A1, ACADM, HMGCS1, MUT, ABAT, ACADSB, ACAD8, AUH |

EC: esophageal cancer; FDR: false discovery rate.

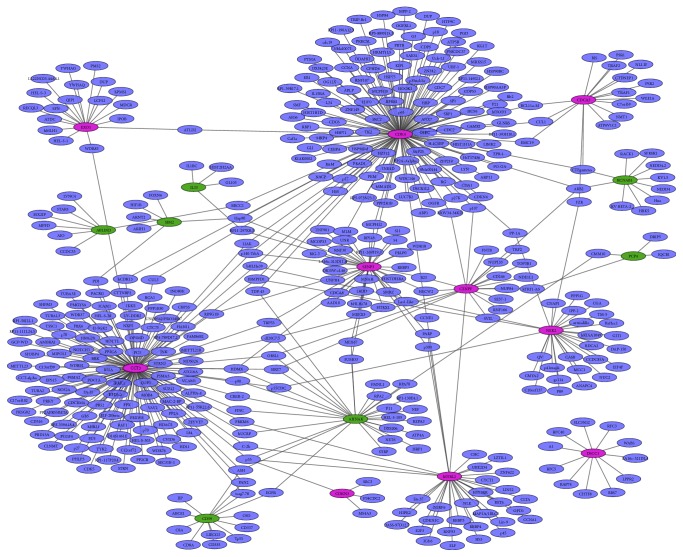

3.4. PPI Network Construction

Based on data from the BioGRID database, the PPI network was the top 10 upregulated and downregulated DEGs which were constructed by Cytoscape software (Figure 1). The network consisted of 451 nodes and 499 edges. In the PPI networks the nodes with high degree are defined as hub proteins. The most significant hub proteins in the PPI network were CDK4 (degree = 132) and CCT3 (degree = 127); as shown in Figure 1, the red circular nodes represent upregulated DEGs and green circular nodes represent downregulated DEGs, respectively.

Figure 1.

The protein-protein network of top 10 up- and downregulated DEGs in EC. The green circular nodes represent downregulation DEGs in EC; the red circular nodes represent downregulation DEGs in EC. Solid lines indicate interaction between DEGs and proteins.

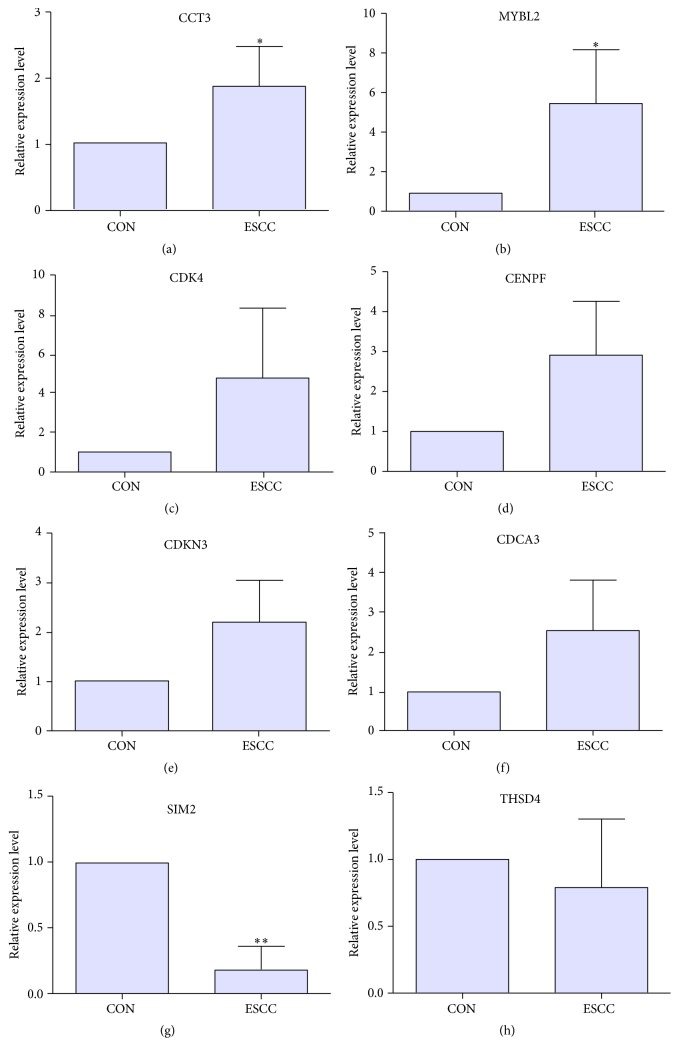

3.5. qRT-PCR Validation of DEGs in EC Tissues

To validate the microarray analysis data, the expression of DEGs including CCT3, CDK4, MYBL2, CENPF, CDKN3, CDCA3, THSD4, and SIM2 was detected by qRT-PCR in 5 paired EC tumor and adjacent nontumor tissues. The 5 patients received surgery treatment in Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University. The histological type of 5 subjects was ESCC and the detailed information of subjects was shown in supplementary Table S2. As shown in Figures 2(a) and 2(b) the expression level of CCT3 and MYBL2 was significantly upregulated in ESCC. CDK4, CENPF, CDKN3, and CDCA3 had the upregulation tendency in ESCC (Figures 2(c)–2(f)), respectively. SIM2 was significantly downregulated in ESCC (Figure 2(g)). THSD4 had the downregulation tendency in ESCC (Figure 2(h)). The qRT-PCR results were matched with the microarray analysis.

Figure 2.

The qRT-PCR validation of the expression level of DEGs in EC compared to adjacent nontumor tissues. (a) CCT3; (b) MYBL2; (c) CDK4; (d) CENPF; (e) CDKN3; (f) CDCA3; (g) SIM2; (h) THSD4. EC: esophageal carcinoma; CON: adjacent nontumor tissues of ESCC. At least three independent experiments were performed for statistical evaluation. qRT-PCR experimental data were expressed as means ± SD. The statistical significance was evaluated using Student's t-test and p < 0.05 was considered as a significant difference.

4. Discussion

CDK4 was identified as the most significantly upregulated gene in our microarray analysis and it had an upregulated tendency in EC tissues through the qRT-PCR validation. CDK4 was the hub protein and interacted with 132 genes in the regulatory network. CDK4 was significantly enriched in cell cycle, measles, small cell lung cancer, and pathways in cancer. CDK4 encodes cyclin-dependent kinase 4, a member of the Ser/Thr protein kinase family, which plays an important role in cell cycle G1 phase progression and G1/S transition. In our study, CDK1, CDK6, and CDK10 showed upregulation in EC. CDK1, CDK6, and CDK4 were significantly enriched in cell cycle pathway. CDK4 is overexpression in several cancer comprising of breast cancer, pancreas cancer, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and colorectal cancer [20–23]. Downregulation of MALAT1 (long noncoding RNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1) inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in vitro and in vivo through miR-124 downregulation and CDK4 upregulation [20, 24]. Overexpression of cyclin D1/CDK4 is regulated by CEACAM6 and promotes cell proliferation in human pancreatic carcinoma [21]. CDK4 and CDK6 expression are decreased by miR-1 and contribute to inhibition of cell cycle progression and metastasis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma [22].

CCT3 was the top 3 upregulation DEGs in EC (Table 2). The qRT-PCR displayed that CCT3 was significantly upregulated in EC, which was in accordance with our microarray analysis (Figure 2). CCT3 interacted with 127 genes in the PPI network (Figure 1). CCT3 encodes chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 3, a molecular chaperone, which is a member of the chaperonin containing TCP1 complex (CCT). In our study, CCT2, CCT4, CCT5, and CCT7 were upregulated in EC compared to normal controls, respectively. CCT3 depletion suppresses cell proliferation by inducing mitotic arrest at prometaphase and apoptosis eventually in HCC in vitro. Clinically, overexpression of CCT3 predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after hepatectomy [25, 26]. CCT3 is significantly associated with carboplatin resistance in ovarian cancer patients after surgery treatment [27]. The proteomic-based study shows that patients with cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) which are positive for CCT3 and CCT3 might be potential biomarker for the diagnosis of CCA [28]. To our knowledge, this is the first report about CCT3 expressed status in EC and the biological function of upregulated CCT3 in EC needs further exploration.

THSD4 was the most downregulated DGE in EC through microarray analysis. The expression level of THSD4 had no significance in EC compared to normal controls but had the downregulated tendency in EC. THSD4 encodes thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 4. The methylated status of THSD4 shows positive correlation with short survival in glioblastoma patients and hypermethylation of THSD4 indicates poor survival [29]. The expression of THSD4 is regulated by GATA3 and mediates transformation of normal cells into breast cancer through deregulation of THSD4 [30]. The role of downregulated THSD4 in EC is unclear, and the investigation needs to be carried out in the future.

SIM2 was significantly downregulated in EC (Figure 2). SIM2 encodes single-minded family bHLH transcription factor 2. SIM2-s was dysregulated in glioma, prostate cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and ESCC [31–35]. SIM2s is downregulated in human breast cancer samples and it suppresses tumor activity through decreased expression of matrix metalloprotease-3. In breast cancer, SIM2s is downregulated. It is a key regulator of mammary-ductal development. SIM2s inhibition is associated with cell invasive and EMT-like phenotype through regulating matrix metalloprotease-3 expression [34, 36] It is reported that SIM2s is downregulated in 70% ESCC tissues, which is consistent with our qRT-PCR verification [35]. SIM2 overexpression results in increase of drug- and radio-sensitivities in ESCC in vivo and in vitro and patients with high expression level of SIM2 are associated with favorable prognosis before chemotherapy [35]. It is suggested that SIM2 plays vital roles in EC onset and progression.

MYBL2, CENPF, CDKN3, and CDCA3 were upregulated in EC tissues (Figure 2). MYBL2 is frequently amplified in gastroesophageal cancer cell lines and Barrett's adenocarcinoma [37, 38]. CENPF is frequently amplified in region around 1q32-q41 and is overexpressed in ESCC cell line [39]. CDKN3 is upregulated in 68.0% of the epithelial ovarian cancer samples and lung adenocarcinoma patients and is correlated with poor patient survival [40, 41]. CDCA3 expression status in EC was firstly reported in our study. The molecular mechanism of MYBL2, CENPF, CDKN3, and CDCA3 in EC is needed to be explored.

5. Conclusions

We identified 1955 DEGs comprising 919 upregulated genes and 1036 downregulated genes in EC. DEGs including CDK4, CCT3, THSD4, and SIM2 were verified in EC tissues through qRT-PCR. CDK4 and CCT3 were hub proteins in the PPI interaction network. We found that some genes including CDK4, CCT3, THSD4, and SIM2 may play essential roles in EC through cell cycle, RNA transport, Endocytosis, and focal adhesion signaling pathways. The genes could also be considered as potential candidate biomarkers for therapeutic targets for this malignancy. Furthermore, our study would shed light on the molecular mechanism underlying tumorigenesis of EC.

Supplementary Material

The expression level of 8 candidate genes with dysregulation in esophageal carcinoma were validated through qRT-PCR. The primers for amplification of 8 genes in qRT-PCR was shown in supplementary S3.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by Major Medical Scientific Research Subject of Hebei Province (zd2013044).

Competing Interests

All of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Siegel R., Naishadham D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enzinger P. C., Mayer R. J. Esophageal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(23):2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/nejmra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P. D., et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnal M. J. D., Arenas Á. F., Arbeloa Á. L. Esophageal cancer: risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in Western and Eastern countries. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;21(26):7933–7943. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song X., You W., Zhu J., et al. A genetic variant in miRNA-219-1 is associated with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese Kazakhs. Disease Markers. 2015;2015:10. doi: 10.1155/2015/541531.541531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye B., Ji C.-Y., Zhao Y., Li W., Feng J., Zhang X. Single nucleotide polymorphism at alcohol dehydrogenase-1B is associated with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell International. 2014;14(1, article 12) doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng H., Wang K., Chen X., et al. MicroRNA-330-3p functions as an oncogene in human esophageal cancer by targeting programmed cell death 4. American Journal of Cancer Research. 2015;5(3):1062–1075. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrnes K. A., Phatak P., Mansour D., et al. Overexpression of miR-199a-5p decreases esophageal cancer cell proliferation through repression of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase-11 (MAP3K11) Oncotarget. 2016;7(8):8756–8770. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang M., Linghu E., Zhan Q., et al. Methylation of DACT2 accelerates esophageal cancer development by activating Wnt signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;7(14):17957–17969. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y., Qin X., Wu J., et al. Association of promoter methylation of RUNX3 gene with the development of esophageal cancer: a meta analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107598.e107598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautier L., Cope L., Bolstad B. M., Irizarry R. A. Affy—analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth G. K. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Springer; 2005. Limma: linear models for microarray data; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B: Methodological. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvord W. G., Roayaei J., Stephens R., et al. The DAVID gene functional classification tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biology. 2007;8(9, article R183) doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanehisa M., Araki M., Goto S., et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36(supplement 1):D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatr-Aryamontri A., Breitkreutz B.-J., Oughtred R., et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(1):D470–D478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nature Protocols. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng T., Shao F., Wu Q., et al. miR-124 downregulation leads to breast cancer progression via LncRNA-MALAT1 regulation and CDK4/E2F1 signal activation. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):16205–16216. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan L., Wang Y., Wang Z.-Z., et al. Cell motility and spreading promoted by CEACAM6 through cyclin D1/CDK4 in human pancreatic carcinoma. Oncology Reports. 2016;35(1):418–426. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao H., Zeng J., Li H., et al. MiR-1 downregulation correlates with poor survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma where it interferes with cell cycle regulation and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2015;6(15):13201–13215. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., Yu S., Cui L., et al. Role of SMC1A overexpression as a predictor of poor prognosis in late stage colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1, article 90) doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1085-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng T., Xu D., Tu C., et al. miR-124 inhibits cell proliferation in breast cancer through downregulation of CDK4. Tumor Biology. 2015;36(8):5987–5997. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Wang Y., Wei Y., et al. Molecular chaperone CCT3 supports proper mitotic progression and cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Letters. 2016;372(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui X., Hu Z.-P., Li Z., Gao P.-J., Zhu J.-Y. Overexpression of chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 3 predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;21(28):8588–8604. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i28.8588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pénzváltó Z., Lánczky A., Lénárt J., et al. MEK1 is associated with carboplatin resistance and is a prognostic biomarker in epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Y., Deng X., Zhan Q., et al. A prospective proteomic-based study for identifying potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2013;17(9):1584–1591. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma J., Hou X., Li M., et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling reveals new biomarkers for prognosis prediction of glioblastoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2015;11(6):212–215. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.168188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen H., Ben-Hamo R., Gidoni M., et al. Shift in GATA3 functions, and GATA3 mutations, control progression and clinical presentation in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2014;16(6, article 464) doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su Y., Wang J., Zhang X., et al. Targeting SIM2-s decreases glioma cell invasion through mesenchymal–epithelial transition. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2014;115(11):1900–1907. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su Y., He Q., Deng L., et al. MiR-200a impairs glioma cell growth, migration, and invasion by targeting SIM2-s. NeuroReport. 2014;25(1):12–17. doi: 10.1097/wnr.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao W. H., Qu X. L., Li X. M., et al. Identification of commonly dysregulated genes in colorectal cancer by integrating analysis of RNA-Seq data and qRT-PCR validation. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2015;22(5):278–284. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2015.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laffin B., Wellberg E., Kwak H.-I., et al. Loss of singleminded-2s in the mouse mammary gland induces an epithelial-mesenchymal transition associated with up-regulation of slug and matrix metalloprotease 2. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28(6):1936–1946. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01701-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komatsu M., Sasaki H. DNA methylation is a key factor in understanding differentiation phenotype in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Epigenomics. 2014;6(6):567–569. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwak H.-I., Gustafson T., Metz R. P., Laffin B., Schedin P., Porter W. W. Inhibition of breast cancer growth and invasion by single-minded 2s. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(2):259–266. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg C., Geelen E., IJszenga M. J., et al. Spectrum of genetic changes in gastro-esophageal cancer cell lines determined by an integrated molecular cytogenetic approach. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2002;135(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albrecht B., Hausmann M., Zitzelsberger H., et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization for the detection of DNA sequence copy number changes in Barrett's adenocarcinoma. The Journal of Pathology. 2004;203(3):780–788. doi: 10.1002/path.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komatsu S., Imoto I., Tsuda H., et al. Overexpression of SMYD2 relates to tumor cell proliferation and malignant outcome of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1139–1146. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fan C., Chen L., Huang Q., et al. Overexpression of major CDKN3 transcripts is associated with poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma. British Journal of Cancer. 2015;113(12):1735–1743. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li T., Xue H., Guo Y., Guo K. CDKN3 is an independent prognostic factor and promotes ovarian carcinoma cell proliferation in ovarian cancer. Oncology Reports. 2014;31(4):1825–1831. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J., Chen Z., Tian L., et al. LncRNA profile study reveals a three-lncRNA signature associated with the survival of patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gut. 2014;63(11):1700–1710. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen K., Li Y., Dai Y., et al. Characterization of tumor suppressive function of cornulin in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068838.e68838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long A., Giroux V., Whelan K. A., et al. WNT10A promotes an invasive and self-renewing phenotype in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(5):598–606. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimokuni T., Tanimoto K., Hiyama K., et al. Chemosensitivity prediction in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: novel marker genes and efficacy-prediction formulae using their expression data. International Journal of Oncology. 2006;28(5):1153–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mello B. P., Abrantes E. F., Torres C. H., et al. No-match ORESTES explored as tumor markers. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(8):2607–2617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The expression level of 8 candidate genes with dysregulation in esophageal carcinoma were validated through qRT-PCR. The primers for amplification of 8 genes in qRT-PCR was shown in supplementary S3.