Abstract

Exercise can improve clinical outcomes in people with severe mental illness (SMI). However, this population typically engages in low levels of physical activity with poor adherence to exercise interventions. Understanding the motivating factors and barriers towards exercise for people with SMI would help to maximize exercise participation. A search of major electronic databases was conducted from inception until May 2016. Quantitative studies providing proportional data on the motivating factors and/or barriers towards exercise among patients with SMI were eligible. Random-effects meta-analyses were undertaken to calculate proportional data and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for motivating factors and barriers toward exercise. From 1468 studies, 12 independent studies of 6431 psychiatric patients were eligible for inclusion. Meta-analyses showed that 91% of people with SMI endorsed ‘improving health’ as a reason for exercise (N = 6, n = 790, 95% CI 80–94). Among specific aspects of health and well-being, the most common motivations were ‘losing weight’ (83% of patients), ‘improving mood’ (81%) and ‘reducing stress’ (78%). However, low mood and stress were also identified as the most prevalent barriers towards exercise (61% of patients), followed by ‘lack of support’ (50%). Many of the desirable outcomes of exercise for people with SMI, such as mood improvement, stress reduction and increased energy, are inversely related to the barriers of depression, stress and fatigue which frequently restrict their participation in exercise. Providing patients with professional support to identify and achieve their exercise goals may enable them to overcome psychological barriers, and maintain motivation towards regular physical activity.

Key words: Exercise, physical activity, physical health, psychosis, schizophrenia

Introduction

People with severe mental illness (SMI) experience a premature mortality of around 15–20 years, largely due to inequalities in physical health (Ribe et al. 2014). For instance, people with SMI have a significantly higher risk of obesity, hyperglycaemia and metabolic syndrome, all of which contribute towards the development of cardiovascular diseases (Gardner-Sood et al. 2015). Many of these physical health issues are related to modifiable risk factors which can be treated and attenuated through lifestyle changes, including exercise and diet (McNamee et al. 2013; Curtis et al. 2016). This is particularly important for those receiving antipsychotic treatment since these medications greatly increase cardio-metabolic risk when combined with a sedentary lifestyle (McNamee et al. 2013; Vancampfort et al. 2015b).

People with SMI engage in significantly less vigorous exercise, and significantly greater amounts of sedentary behaviour than health controls (Stubbs et al. 2016a, b ; Vancampfort et al. 2016a). This inactivity is predictive of a range of adverse health outcomes including obesity, diabetes and medical co-morbidity among people with SMI (Vancampfort et al. 2013a, b ; Suetani et al. 2016). It is also associated with more severe negative symptoms and poor socio-occupational functioning (Vancampfort et al. 2012; Suetani et al. 2016).

An increasing body of research demonstrates that exercise interventions can improve physical health and reduce psychiatric symptoms in people with major depression and psychotic disorders (Rosenbaum et al. 2014; Firth et al. 2015). Exercise has also been found to reduce negative symptoms and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia (Firth et al. 2015; Kimhy et al. 2015); aspects of the illness which are often left untreated and particularly influential on long-term functioning (Galletly, 2009; Arango et al. 2013). Thus, proper implementation of exercise within the care of people with SMI could reduce cardio-metabolic risk and the associated mortality, while also facilitating functional recovery.

The optimal modality of exercise interventions for people with SMI is yet to be established. A recent meta-analysis suggests that various exercise modalities can be effective for improving outcomes in SMI, although only if a sufficient total volume of activity is achieved (Firth et al. 2015). Clinical trials have also found that significant benefits for depressive and psychotic symptoms only occur among participants who achieve sufficient amounts of exercise (Hoffman et al. 2011; Scheewe et al. 2013). Therefore, training programmes which can maximize adherence to exercise in SMI may be the most effective.

Meta-syntheses of the qualitative literature have previously examined the factors which may encourage or prevent exercise participation among people with SMI (Mason & Holt, 2012; Soundy et al. 2014a). For instance, improving self-identity and body image is a valued outcome of exercise programmes, while the sedative effects of psychotropic medications can inhibit physical activity (Mason & Holt, 2012; Soundy et al. 2014a). Although valuable, qualitative investigations can be influenced by interviewers’ biases, and results may only represent a subset of the population. Data from survey-based studies may therefore provide a more accurate representation of the entire patient group.

Improving our understanding of desired outcomes of exercise among people with SMI could enhance health promotion initiatives, and inform the development of interventions that are both motivating and rewarding for patients. Furthermore, determining the most common barriers would help to optimize resource allocation when delivering exercise services in clinical practice. Thus, we conducted a systematic review of studies reporting quantitative data on motivating factors and barriers towards exercise for people with SMI. We also quantified patients’ responses in these surveys using meta-analytical techniques to determine which were most pertinent for this patient group.

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

An electronic database search of Ovid Medline, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), PsycINFO, EMBASE, and the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) database, using the search algorithm: ‘exercise’ or ‘physical activity’ or ‘sport*’ AND ‘psychiatric’ or ‘severe mental’ or ‘serious mental’ or ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘psychosis’ or ‘bipolar’ or ‘manic depress*’ or ‘major depress*’ or ‘clinical depress*’ or ‘depressive disorder’ AND ‘motiv*’ or ‘barriers’ or ‘incentives’ or ‘attitudes’ or ‘preferences’ or ‘advantages’ or ‘disadvantages’ was conducted in May 2016, considering articles published from database inception. A search of Google Scholar was conducted using the same key words to identify any additional relevant articles. The reference lists of retrieved articles were also searched.

Only English-language research articles in peer-reviewed journals were included in this review. Eligible samples were those in which >80% of the sample had a diagnosis of a SMI (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder) and/or were currently receiving treatment for SMI. Studies which inferred the presence of SMI solely from participants’ response to screening questionnaires were excluded if no diagnosis or current treatment for SMI could be confirmed. Eligible studies were those reporting proportional data on motivating factors and/or barriers towards physical activity among people with SMI, from questionnaires, surveys or other quantitative methods. Studies which used only qualitative methods were not eligible for inclusion, as these have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (Mason & Holt 2012; Soundy et al. 2014a). ‘Motivating factors’ were defined as any outcome of exercise perceived by patients to be a reason for increasing physical activity. ‘Barriers’ were defined as any physiological, psychological or socio-ecological conditions reported to reduce patients’ participation in exercise.

Data extraction and data analysis

Articles were screened by two reviewers (J.F. and S.R.) to assess eligibility. Disagreements on eligibility were resolved through discussion. A systematic tool was developed (see Supplementary Table S1) to extract all relevant quantitative data from each study into the following categories:

-

(1)

Motivating factors for exercise

-

(a)

Physical: physical health; fitness; strength; weight loss.

-

(b)

Psychological: well-being; enjoyment; reduce distress; mood; self-esteem.

-

(c)

Socio-ecological: socializing; health professional advice; routine.

-

(a)

-

(2)

Barriers to exercise

-

(a)

Physical: physical illness; tiredness/fatigue.

-

(b)

Psychological: distress; depression; motivational; self-confidence; safety.

-

(c)

Socio-ecological: cost; access to facilities; time; support; insufficient information.

-

(a)

Information on study characteristics (sample size, demographics, location, care setting) was also extracted from each study, and is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Responses to survey items on motivating factors for exercise among people with severe mental illness

| Category | Survey item | Average response a |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Physical health factors | ||

| General health | ||

| Bassilios et al. (2014) | Exercise for physical benefits | 84% of those intending to exercise |

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Exercise is important for physical health | 88% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercise will make me healthier | 95% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | Improve my health or reduce my risk of disease | Rated 4.3/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To maintain good health | 98% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | It would improve my health | Rated 4.3/5 on importance scale |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise is beneficial for my physical health | 100% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Exercise is important for physical health | 90% agreed |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ | 61% said ‘to stay healthy’ |

| Fitness/energy | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | I will have more energy | 75% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would increase my energy levels | Rated 4.2/5 for importance |

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | To increase fitness/energy | 68% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To improve my energy levels | 88% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | It would help me to stay fit | Rated 4.2/5 on importance scale |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | I would have more energy | Rated 3.9/5 on importance scale |

| Kane et al. (2012) | Fitness | Rated 6/7 as a motivating factor |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise improves my cardiovascular fitness | 78% agreed. Avg. rating = 7.7/10 |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ (open-answer) | 59% said ‘to get fit’ |

| Strength | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercise makes me feel strong | 83% agreed |

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | To increase sporting ability/strength | 50% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To build up my strength | 81% agreed |

| Body weight | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercise will help me lose weight | 80% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would help control my weight | Rated 3.8/5 for importance |

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | To lose weight | 61% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To control my weight | 98% agreed |

| Appearance | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | I will look better | 85% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would improve my muscle tone | Rated 4.2/5 for importance |

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | To increase muscle tone | 50% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To improve my appearance | 64% agreed |

| Kane et al. (2012) | Appearance | Rated 5.5/7 as a motivating factor |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise improves my body shape and/or tone | 82% agreed. Avg. rating = 8.3/10 |

| (2) Psychological factors | ||

| General well-being | ||

| Bassilios et al. (2014) | Exercise for psychological benefits | 27% of those intending to exercise |

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Exercise is important for mental health | 85% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercising makes me feel better | 90% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Beneficial for managing psychological well-being | 95% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To give me space to think | 73% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise is beneficial to my mental health | 99% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Exercise is important for mental health | 72% agreed |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ | 38% ‘to help psychiatric problems’ |

| Enjoyment | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Enjoys exercise very much so or extremely so | 30% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | I will have fun | 85% agreed |

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | For having fun | 54% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Because I enjoy exercising | 54% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | I would have fun | Rated 4/5 on importance scale |

| Kane et al. (2012) | Interest in exercise | Rated 5/7 as a motivating factor |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I have fun exercising | 46% agreed. Avg. rating = 5.6/10 |

| Ussher (2007) | Enjoys exercise very much so or extremely so | 57% agreed |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ | 57% for ‘enjoyment’ |

| Emotions and mood | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercise helps me manage my mood | 75% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To improve my emotional well-being | 94% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | It improves my mood and ability to cope with stress | 70% agreed. Avg. rating = 7.1/10 |

| Reducing stress | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercise helps me manage stress | 85% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would help me feel less tense or stressed | Rated 4.1/5 for importance |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would help me feel less angry or irritable | Rated 3.9/5 for importance |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would take my mind off things | Rated 4/5 for importance |

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | Taking your mind off things | 64% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | To help manage my stress | 95% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | It improves my mood and ability to cope with stress | 70% agreed. Avg. rating = 7.1/10 |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ | 54% ‘to reduce stress’ |

| Self-confidence | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Exercise makes me feel more self-confident | 88% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | I will feel better about myself | 90% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would improve how I feel about myself | Rated 4.4/5 for importance |

| Firth et al. (2015) | Being more confident in a gym | 64% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | I would feel better about myself | Rated 3.9/5 on importance scale |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise makes me feel good about myself | Rated 7.54/10 for relevance |

| Sleep | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | I will sleep better | 80% agreed |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would help me sleep better | Rated 3.9/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | It helps me sleep better | 79% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I can sleep better if I exercise | 59% agreed. Avg. rating = 6.6/10 |

| (3) Socio-ecological factors | ||

| Social aspects | ||

| Firth et al. (2016a– c ) | Meeting new people’ | 29% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | I enjoy the social aspects | 27% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | People important to me would be happy if I did | Rated 3.7/5 on importance scale |

| Kane et al. (2012) | Social | Rated 3.4/7 as a motivating factor |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercising is a chance for me to see people | 27% agreed. Avg. rating = 4.1/10 |

| Professional support | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Would exercise more with doctors’ advice | 63% agreed |

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Instructor's help would increase levels of exercise | 68% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | I exercise because my doctor advised me to | 61% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Would exercise more with doctors’ advice | 58% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Instructor's help would increase levels of exercise | 58% agreed |

| Daily routine | ||

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I have nothing better to do with my time | Rated 2.87/10 for relevance |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise helps to structure my day | Rated 4.96/10 for relevance |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ | 45% ‘to get into a routine’ |

| Wynaden et al. (2012) | ‘Why do you attend the gym?’ | 42% ‘to pass time’ |

Bold indicates inclusion in meta-analyses.

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

We sought to establish the overall prevalence of motivating factors or barriers towards exercise proportion among people with SMI. Therefore, where any specific motivating factor/barrier had been examined by ⩾3 independent studies, data was pooled using proportional meta-analysis in StatsDirect 2.7 (StatsDirect, 2005). A random-effects model was applied in all meta-analyses, in order to account for expected heterogeneity between studies (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986). The degree of variance between studies was assessed with Cochran's Q and indexed as I2, which estimates the amount of variance caused by between-study heterogeneity, rather than chance. As wording of questions can differ between studies, combinability of study data for meta-analyses was first established through agreed selection by two reviewers (J.F. and S.R.).

Search results

Fig. 1 shows the full study selection process. The initial database search returned 1534 results. This was reduced to 1163 after duplicates were removed. A further 1109 articles were excluded after reviewing the titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full text versions were retrieved for 54 articles, of which nine were eligible for inclusion. A further three articles were identified from a similar search of Google Scholar. A total of 12 different studies articles, each with unique samples were eligible for inclusion (Faulkner et al. 2007; Ussher, 2007; Sylvia et al. 2009; Gorczynski et al. 2010; Kane et al. 2012; Wynaden et al. 2012; Carpiniello et al. 2013; Bassilios et al. 2014; Deighton & Addington 2014; Fraser et al. 2015; Klingaman et al. 2014; Firth et al. 2016a). Additional data was obtained for four studies from the corresponding authors (Sylvia et al. 2009; Gorczynski et al. 2010; Deighton & Addington, 2014; Firth et al. 2016a).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic search and study selection.

Included studies and participant details

Characteristics of included studies are detailed in Supplementary Table S2. Three were conducted in the United States, three in Canada, three in Australia, two in the UK, and one in Italy. There were a total of 6431 psychiatric patients within these studies; 85.5% with schizophrenia, 6.2% with an unspecified SMI, 2.3% with bipolar or major depression, and 6% other/unknown diagnosis. Where specified, 65% were community-based outpatients while 35% were inpatients within psychiatric units. The median age was 42.6 years (range = 19.8–55 years). Samples ranged from 26–86% male (median = 62%). Of 5757 subjects, 50% belonged to minority groups within their respective countries, while 50% were white. Five studies (n = 470) also reported employment, showing that 68% of participants were unemployed. All survey items which were combined for meta-analyses are highlighted in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Responses to items on barriers towards exercise among people with SMI

| Category | Survey item | Average response a |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Physical barriers | ||

| Poor physical health | ||

| Bassilios et al. (2014) | Physical health problems as a barrier | 28% of non-vigorous exercisers |

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Illness | 19.6% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Physical health problems | 44% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Exercise will not change my physical health | Avg. rating = 1.7/10 |

| Ussher (2007) | Illness | 15% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Feel too unwell | 60% agreed |

| Tiredness/low energy | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Too tired | 38.4% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of energy | ‘Sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would leave me feeling tired | Rated 2.1/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Feel too tired | 74% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Lack of energy | 76% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Too tired | 27.8% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I do not have enough energy | 69% agreed. Avg. rating = 7.4/10 |

| Ussher (2007) | Too tired | 20% agreed |

| (2) Psychological barriers | ||

| Stress/depression | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Unconfident about ability to exercise if sad/stressed | 76.4% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Stress/depression | 48% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Unconfident about ability to exercise if sad/stressed | 58% agreed |

| Low motivation | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Poor desire | 25.4% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of motivation | ‘Sometimes a barrier’ |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Lack of motivation | 73% agreed |

| Disinterest | ||

| Bassilios et al. (2014) | Disinterest as a barrier | 55% of non-vigorous exercisers |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of programmes that interest me | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Do not enjoy physical activity | 27% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Do not like exercise | 22.4% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I do not have enough interest in exercising | 48% agreed. Avg. rating = 5.5/10 |

| Self-confidence | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Don't like how my body looks | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Failure to achieve exercise goals in the past | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of skills or ability to do a certain type of exercise | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | I would worry about what other people think of me | Rated 1.4/5 for importance |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | I would be worried that I would not be very good at it | Rated 2/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Feel too shy/embarrassed | 36% agreed |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Not the sporty type | 29% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | I feel embarrassed if people see me doing it | Rated 1.7/5 on importance scale |

| Ussher (2007) | Self-consciousness | 7% agreed |

| Feeling unsafe | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Feel unsafe going outdoors | 9% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Feeling uncomfortable or intimidated | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Fear of making an existing condition worse | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Feels unsafe to go outside | 16% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Safety concerns | 14% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Feel unsafe going outdoors | 9% agreed |

| Fear of injury | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Afraid of getting injured | 5.8% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Fear of injury or re-injury | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | I might injure myself | Rated 2/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Worried I might get injured | 9% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Afraid of getting injured | 8% agreed |

| (3) Socio-ecological barriers | ||

| Lack of time | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Takes too much time | 23.9% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of time | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would take time away from other things | Rated 2.1/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | I do not have enough time | 13% agreed |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | It takes time away from doing other things | Rated 2.7/5 on importance scale |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Too little time | 13.9% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Job/work | 5.6% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Daily routine do not include exercise | 26.5% agreed |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I do not have enough time to exercise | 32% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Takes too much time | 12% agreed |

| Lack of support | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Would receive little help with exercise from others | 65.3% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of support from others | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | I would need too much help from others | Rated 2.5/5 on importance scale |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Lack of support/encouragement | 19.8% agreed |

| Ussher (2007) | Would receive little help with exercise from others | 68% agreed |

| Lack of information | ||

| Carpiniello et al. (2013) | Not sure what to do | 15% agreed |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of knowledge about how to exercise | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | I don't know how to do physical activities | Rated 1.8/5 for importance |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | Difficult to find out what to do and where to do it | Rated 2.1/5 for importance |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | There is too much I have to learn to do it | Rated 2.3/5 on importance scale |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | Not know how to exercise/what to do in a gym | 11% agreed. Avg. rating = 2.9/10 |

| Ussher (2007) | Not sure what to do | 6% agreed |

| Cost | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Cost of physical activity programme | ‘Sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | It would cost too much | Rated 2.4/5 for importance |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Cost | 19% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | Too little money | 24.7% agreed |

| Access to facilities | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of transportation | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Lack of facilities near by | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Lack of access to facilities | 41% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | No place to walk or be active | 11.2% agreed |

| Klingaman et al. (2014) | No transport | 11.8% agreed |

| Training partner | ||

| Deighton & Addington (2014) | Do not have anyone to go with | ‘Never or sometimes a barrier’ |

| Faulkner et al. (2007) | I would have to do it by myself | Rated 2.7/5 for importance |

| Gorczynski et al. (2010) | I would have to do it by myself | Rated 2.8/5 on importance scale |

| Sylvia et al. (2009) | I have no one to exercise with | Rated 2.6/10 for relevance |

Bold indicates inclusion in meta-analysis.

Physical health motivations

Meta-analyses of proportional data are displayed in Fig. 2. The most endorsed reason for exercising was to improve general physical health; endorsed by 91% of people with SMI (N = 6, n = 790, 95% CI 80–94, Q = 81, p < 0.01, I2 = 94%). Two studies which examined motivations for exercise using Likert scales also found that general health improvement ranked higher than all other options (Faulkner et al. 2007; Gorczynski et al. 2010).

Fig. 2.

Proportional meta-analyses of motivating factors for exercise in severe mental illness. The forest plot shows the % of patients agreeing with each motivating factors (box points) and the 95% confidence intervals (horizontal lines). Individual study items used in meta-analyses are shown in Table 1.

Increasing fitness/energy was the most widely assessed physical health motivation (N = 5, n = 549). This was a motivating factor for 75% of respondents (95% CI 64.9–83.4, Q = 19, p < 0.01, I2 = 79%) and ranked as ‘highly important’ in three Likert-scale studies (Faulkner et al. 2007; Sylvia et al. 2009; Gorczynski et al. 2010). ‘Improving appearance’ and ‘losing weight’ were examined in only three studies each, but received high rates of endorsement of 77% (n = 465, 95% CI 64–88, Q = 13.3, p < 0.01, I2 = 85%) and 83%, respectively (n = 169, 95% CI 54–99, Q = 30, p < 0.01, I2 = 93%). ‘Improving strength’ averaged 72% endorsement (N = 3, n = 169, 95% CI 55–87, Q = 10, p < 0.01, I2 = 81%).

Psychological motivations

As shown in Fig. 2, overall mental health, reducing stress and managing mood were equally popular motivating factors, with 80% (N = 6, n = 788, 95% CI 62–93, Q = 134, p < 0.01, I2 = 96%), 78% (N = 4, n = 520, 95% CI 59–92, Q = 50, p < 0.01, I2 = 94%) and 81% (N = 3, n = 464, 95% CI 62–93, Q = 32, p < 0.01, I2 = 94%) of patients agreeing, respectively. Improved sleeping patterns was a motivating factor for 72% of patients (N = 3, n = 464, 95% CI 55.6–86, Q = 20, p < 0.01, I2 = 90%). Enjoyment of exercise was only endorsed by 54% of respondents (n = 807, 95% CI 42.5–64.6, Q = 53, p < 0.01, I2 = 89%). Likert scales studies also found that mental health benefits and enjoyment of exercise scored moderate-to-high for importance as reasons for exercise. The benefits of exercise for self-confidence were assessed in five studies. Although unsuitable for meta-analysis, five studies which assessed the benefits of exercise for self-confidence showed that this is a broadly accepted and valued reason to exercise (See Table 1).

Socio-ecological motivations

Social aspects of exercise seen as motivating factors by 27% of patients (N = 3, n = 452, 95% CI 23–32, Q = 0.1, p < 0.097, I2 = 0%). In Likert-scale studies, social aspects scored the lowest of all options presented (Sylvia et al. 2009; Gorczynski et al. 2010; Kane et al. 2012). Similarly, only a minority of participants saw ‘improving daily routine’ as an important reason for exercise (Sylvia et al. 2009; Wynaden et al. 2012). In contrast, three independent studies found that ‘professional support’ was perceived as a motivating factor for increasing exercise by the majority of patients (Ussher, 2007; Sylvia et al. 2009; Carpiniello et al. 2013).

Physical health barriers

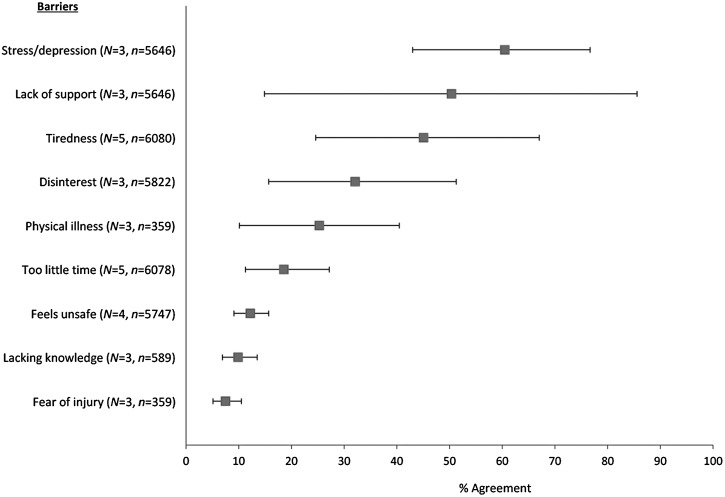

Fig. 3 shows meta-analyses of barriers towards exercise. Physical illness and poor health was a barrier for 25% of participants (N = 3, n = 359, 95% CI 10–41, Q = 64, p < 0.01, I2 = 92%). Tiredness/low energy was more common, reported by 45% of patients (N = 5, n = 6080, 95% CI 25–67, Q = 322, p < 0.01, I2 = 99%) and rated as 7.4/10 on relevance scales (Sylvia et al. 2009). Two studies also showed that patients with long-term schizophrenia were more affected by tiredness than healthy controls (Carpiniello et al. 2013; Klingaman et al. 2014). However, this difference did not exist between patients with first-episode psychosis and healthy controls (Deighton & Addington, 2014).

Fig. 3.

Proportional meta-analyses of barriers to exercise in severe mental illness. The forest plot shows the % of patients experiencing each barrier (box points) and the 95% confidence intervals (horizontal lines). Individual items combined for meta-analysis are shown in Table 2.

Psychological barriers

Proportional meta-analyses showed substantial differences in psychological barriers. ‘Stress/depression’ was a barrier to exercise for 61% of respondents (N = 3, n = 5646, 95% CI 43–77, Q = 48, p < 0.01, I2 = 96%), whereas ‘disinterest in exercise’ was a barrier for only 32% (N = 3, n = 5822, 95% CI 16–51, Q = 96, p < 0.01, I2 = 98%). Feeling unsafe and fears of injury were even less common, at 12% (N = 4, n = 5747, 95% CI 9–16, Q = 7, p = 0.07, I2 = 57%) and 8% (N = 3, n = 359, 95% CI 5–11, Q = 0.9, p = 0.64, I2 = 0%), respectively. Data from five studies assessing confidence-related barriers was unsuitable for meta-analyses, but collectively showed that this was only a concern for a minority of participants (7–36%), and to a limited extent; consistently scoring <2/5 on Likert scales of importance (Table 2).

Data on ‘low motivation’ was also unsuitable for proportional meta-analysis. However, all three studies which assessed this found that motivational deficits were among the most common psychological barriers towards exercise (Carpiniello et al. 2013; Deighton & Addington, 2014; Fraser et al. 2015). Furthermore, patients with long-term schizophrenia experienced motivational barriers significantly more than healthy controls (Carpiniello et al. 2013). Again, however, there was no significant difference in the early stages of illness (Deighton & Addington, 2014).

Socio-ecological barriers

The most frequently experienced practical barrier was a ‘lack of support’, reported by 50% of respondents (N = 3, n = 5646, 95% CI 15–86, Q = 240, p < 0.01, I2 = 99%). This was significantly more prevalent among schizophrenia patients than healthy controls (Carpiniello et al. 2013; Klingaman et al. 2014). People with first-episode psychosis also scored these items higher than controls, although differences were not statistically significant (Deighton & Addington, 2014). ‘Lack of training partner’ was a moderately ranked barrier, but was regarded as significantly more important by those patients who were interested in increasing their exercise (Faulkner et al. 2007).

‘Lack of time’ was the most widely investigated practical barrier, although only 19% of respondents identified this as a barrier (N = 5, n = 6078, 95% CI 11.3–27.2, Q = 68, p < 0.01, I2 = 94%). Three studies using Likert scales also found that time-related barriers were mostly unimportant (Faulkner et al. 2007; Gorczynski et al. 2010; Deighton & Addington, 2014). Furthermore, ‘lack of time’ was significantly less of a barrier for people with SMI than for healthy controls (Deighton & Addington, 2014; Klingaman et al. 2014). Only 10% of patients felt that ‘lack of exercise information’ was a barrier (n = 589, 95% CI 7–14, Q = 3.4, p = 0.18, I2 = 42%). Additional data (unsuitable for meta-analysis) on cost and accessibility of exercise services indicated these were of low importance (See Table 2).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the motivating factors and barriers towards exercise among people with SMI, in order to inform the design and delivery of interventions aiming to increase exercise participation. A total of 12 studies (of 6431 psychiatric patients with predominantly schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorders) were identified. As nine of the 12 studies reviewed had been conducted from 2013 onwards, the evidence/data presented can be considered timely and up-to-date.

Our results show that the primary incentive for engaging in exercise was to improve physical health (Fig. 2). Specifically, weight loss was the single most popular reason for participating in exercise, comparable to the motivating factors identified by the general population (Sherwood & Jeffery, 2000), and unsurprising given the high rates of overweight and obesity among people with SMI (Vancampfort et al. 2015b). Although weight management can be a key motivating factor for initiating an exercise programme, it is important to note (a) the relatively modest contribution of physical activity to weight loss beyond that achieved through dietary interventions (Haskell et al. 2007), and (b) that improvements in mental and physical health outcomes in response to exercise interventions are often achieved independent of weight loss (Firth et al. 2015). While weight management may be an important motivating factor for people with SMI to commence an exercise programme, education and support should be provided to ensure long-term adoption and maintenance regardless of any change in body weight achieved. Furthermore, if weight loss is a primary aim, dietary interventions must be provided as part of best-practice lifestyle interventions (Ward et al. 2015).

The high endorsement of ‘fitness’ as an incentive is encouraging, since this is readily improved by exercise interventions in SMI (Vancampfort et al. 2015a, 2016b), and is more predictive of cardiovascular disease than any other aspect of metabolic health (Myers et al. 2004; Hu et al. 2005). Health promotion programmes should therefore emphasize the benefit of fitness in order to maximize uptake of exercise in this patient group. Furthermore, interventions should ideally be designed by exercise professionals to ensure that they meet basic principles of exercise prescription, in order to exert significant physiological effects and enable patients to achieve realistic fitness goals.

Patients also valued the psychological effects of exercise, and 75% of patients viewed stress reduction/mood enhancement as motivating factors. Recent meta-analyses have shown that exercise can significantly improve psychological well-being among people with SMI and reduce depression (Rosenbaum et al. 2014; Firth et al. 2015). However, the present study also found that stress, depression and low energy often also act as barriers towards exercise.

The most prominent socio-ecological barrier identified across the studies included in this review was a ‘lack of support’. Nonetheless, the majority of patients felt that exercise supervision would enable them to exercise more (Ussher, 2007; Sylvia et al. 2009; Carpiniello et al. 2013). This is congruent with the qualitative literature, within which patients with SMI have stipulated that adequate support can overcome many of the barriers faced towards exercise (Soundy et al. 2014b; Firth et al. 2016b).

Although unsupervised interventions which use less resource-intensive methods (such as education or behavioural change techniques) may seem more cost effective than supervised exercise, this may not be the case for people with SMI. Several recent meta-analyses of exercise interventions in this population have shown that interventions which provide professional support have better adherence to physical activity and significantly greater effects on cardiorespiratory fitness (Vancampfort et al. 2015c, 2016b; Stubbs et al. 2016c). Since both physical activity and fitness are strong predictors of cardiovascular risk and all-cause mortality (Hu et al. 2005; Kodama et al. 2009), supervised interventions which effectively target these variables may ultimately prove more financially worthwhile for improving long-term health outcomes (Vancampfort et al. 2015c, 2016b).

Previous intervention studies have further shown that whereas exercise access and advice is ineffective for increasing physical activity in SMI (Archie et al. 2003; Bartels et al. 2013), providing adequate social support does enable patients to achieve sufficient levels of moderate-to-vigorous exercise (Bartels et al. 2013; Firth et al. 2016c). Although there is currently a lack of cost-effectiveness research examining supervised exercise in SMI, financial reports of exercise interventions for diabetes, mild depression and heart disease indicate that professionally delivered training programmes produce large economic benefits from avoided health system costs (Deloitte Access Economics, 2015).

Limitations

A strength of these findings is the large number of patients (n = 6431) included in the review. Within this, there was also substantial ethnic diversity within the included samples, with 50% belonging to minority groups. However, all of the studies were conducted in western, developed countries, and thus no studies have examined barriers towards exercise among people with SMI in Asia or developing countries. Furthermore, no studies examined differences in motivations or barriers towards exercise between the different ethnic groups within their respective samples. This gap in the literature should be given further consideration in future research, as studies in the general population have shown that beliefs about exercise, and primary reasons for engaging in physical activity, differ significantly between ethnic groups even within the same country (Dergance et al. 2003; Shiu-Thornton et al. 2004). Specifically, those in minority ethnic groups may face additional challenges towards exercise, such as feeling unsafe in their neighbours (Fahlman et al. 2006) or lacking opportunity to engage in culturally appropriate physical activity (Caperchione et al. 2009). Thus, efforts should be undertaken to identify and provide acceptable physical activity interventions for ethnically diverse populations.

Despite the large total sample, one limitation of this review is that some of the motivations and barriers assessed in meta-analyses were examined by as few as three studies. Additionally, some eligible studies did not provide any proportional data, and thus were not included in the meta-analysis at all. Nonetheless, a full systematic review of each eligible study was also undertaken, for consideration alongside the meta-analytic outputs, in order to provide a complete account of all relevant findings.

It should also be considered that the large majority of patients (85%) in this meta-analysis had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, while bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were relatively under-represented among the eligible studies. Thus, future research should examine if the same motivations and barriers towards exercise identified in this review also generalize to patients with SMIs other than schizophrenia. An online survey study of individuals with high depressive symptoms (but without a confirmed SMI) indicates that our findings will generalize beyond schizophrenia, as the most common barriers towards exercise reported by these individual were again low mood and fatigue (Busch et al. 2015), as was observed in our SMI samples (Fig. 3).

A final limitation is that results are based on self-reported data, derived from questionnaires and surveys administered to patients. Therefore, the results could be affected by response bias, or participants lacking sufficient interest/experience with exercise to accurately describe the barriers faced. The findings from patients’ self-report in this study are also congruent with health professionals’ opinions, who also acknowledge the importance of social support in overcoming various barriers towards regular exercise (Soundy et al. 2014c).

Conclusion

People with SMI value exercise for its ability to improve physical health and appearance, and the psychological benefits. However, mental health symptoms, tiredness and insufficient support present substantial barriers for the majority of patients. Taking this into account, exercise training programmes for people with SMI should be designed to improve exercise capacities and cardiorespiratory fitness, while also providing the necessary levels of supervision or assistance for each patient to overcome psychological barriers and achieve their goals. Such interventions would be motivating and rewarding for patients, resulting in higher levels of exercise engagement. This, in turn, could improve physical health outcomes and facilitate functional recovery in SMI.

Acknowledgements

Joseph Firth is funded by an MRC Doctoral Training Scholarship.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001732.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Arango C, Garibaldi G, Marder SR (2013). Pharmacological approaches to treating negative symptoms: a review of clinical trials. Schizophrenia Research 150, 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archie S, Wilson JH, Osborne S, Hobbs H, McNiven J (2003). Pilot study: access to fitness facility and exercise levels in olanzapine-treated patients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48, 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, Barre LK, Jue K, Wolfe RS, Xie H, McHugo G, Santos M, Williams GE (2013). Clinically significant improved fitness and weight loss among overweight persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 64, 729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassilios B, Judd F, Pattison P (2014). Why don't people diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) get enough exercise? Australasian Psychiatry 22, 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AM, Ciccolo JT, Puspitasari AJ, Nosrat S, Whitworth JW, Stults-Kolehmainen MA (2015). Preferences for exercise as a treatment for depression. Mental Health and Physical Activity 10, 68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caperchione CM, Kolt GS, Mummery WK (2009). Physical activity in culturally and linguistically diverse migrant groups to Western Society. Sports Medicine 39, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiniello B, Primavera D, Pilu A, Vaccargiu N, Pinna F (2013). Physical activity and mental disorders: a case-control study on attitudes, preferences and perceived barriers in Italy. Journal of Mental Health 22, 492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J, Watkins A, Rosenbaum S, Teasdale S, Kalucy M, Samaras K, Ward PB (2016). Evaluating an individualized lifestyle and life skills intervention to prevent antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 10, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deighton S, Addington J (2014). Exercise practices of young people at their first episode of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 1, 311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte Access Economics (2015). Value of Accredited Exercise Physiologists in Australia. Canberra (http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economics-value-exercise-physiologists-Australia.pdf). Accessed 2nd June 2016.

- Dergance JM, Calmbach WL, Dhanda R, Miles TP, Hazuda HP, Mouton CP (2003). Barriers to and benefits of leisure time physical activity in the elderly: differences across cultures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51, 863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 7, 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlman MM, Hall HL, Lock R (2006). Ethnic and socioeconomic comparisons of fitness, activity levels, and barriers to exercise in high school females. Journal of School Health 76, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G, Taylor A, Munro S, Selby P, Gee C (2007). The acceptability of physical activity programming within a smoking cessation service for individuals with severe mental illness. Patient Education and Counseling 66, 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J, Carney R, Elliott R, French P, Parker S, McIntyre R, McPhee JS, Yung AR (2016c). Exercise as an intervention for first-episode psychosis: a feasibility study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. Published online: 14 March 2016. doi: 10.1111/eip.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J, Carney R, Jerome L, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR (2016b). The effects and determinants of exercise participation in first-episode psychosis: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 16, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung A (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychological Medicine 45, 1343–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Carney R, Yung AR (2016a). Preferences and motivations for exercise in early psychosis. Acta Psychiatria Scandinavica 134, 83–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser SJ, Chapman JJ, Brown WJ, Whiteford HA, Burton NW (2015). Physical activity attitudes and preferences among inpatient adults with mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 24, 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletly C (2009). Recent advances in treating cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 202, 259–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner-Sood P, Lally J, Smith S, Atakan Z, Ismail K, Greenwood K, Keen A, O'Brien C, Onagbesan O, Fung C (2015). Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in people with established psychotic illnesses: baseline data from the IMPaCT randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine 45, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczynski P, Faulkner G, Greening S, Cohn T (2010). Exploring the construct validity of the transtheoretical model to structure physical activity interventions for individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 34, 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell WL, Lee I-M, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Macera CA, Heath GW, Thompson PD, Bauman A (2007). Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 116, 1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BM, Babyak MA, Craighead WE, Sherwood A, Doraiswamy PM, Coons MJ, Blumenthal JA (2011). Exercise and pharmacotherapy in patients with major depression: one-year follow-up of the SMILE study. Psychosomatic Medicine 73, 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Jousilahti P, Barengo NC, Qiao Q, Lakka TA, Tuomilehto J (2005). Physical activity, cardiovascular risk factors, and mortality among Finnish adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 28, 799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane I, Lee H, Sereika S, Brar J (2012). Feasibility of pedometers for adults with schizophrenia: pilot study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 19, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Bartels MN, Armstrong HF, Ballon JS, Khan S, Chang RW, Hansen MC, Ayanruoh L, Lister A (2015). The impact of aerobic exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurocognition in individuals with schizophrenia: a single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin 41, 859–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingaman EA, Viverito KM, Medoff DR, Hoffmann RM, Goldberg RW (2014). Strategies, barriers, and motivation for weight loss among veterans living with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 37, 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, Sugawara A, Totsuka K, Shimano H, Ohashi Y (2009). Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association 301, 2024–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason OJ, Holt R (2012). Mental health and physical activity interventions: a review of the qualitative literature. Journal of Mental Health 21, 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamee L, Mead G, MacGillivray S, Lawrie SM (2013). Schizophrenia, poor physical health and physical activity: evidence-based interventions are required to reduce major health inequalities. British Journal of Psychiatry 203, 239–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J, Kaykha A, George S, Abella J, Zaheer N, Lear S, Yamazaki T, Froelicher V (2004). Fitness versus physical activity patterns in predicting mortality in men. American Journal of Medicine 117, 912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribe AR, Laursen TM, Sandbæk A, Charles M, Nordentoft M, Vestergaard M (2014). Long-term mortality of persons with severe mental illness and diabetes: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Psychological Medicine 44, 3097–3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Curtis J, Ward PB (2014). Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 75, 964–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheewe T, Backx F, Takken T, Jörg F, Strater AV, Kroes A, Kahn R, Cahn W (2013). Exercise therapy improves mental and physical health in schizophrenia: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 127, 464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW (2000). The behavioral determinants of exercise: implications for physical activity interventions. Annual Review of Nutrition 20, 21–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu-Thornton S, Schwartz S, Taylor M, LoGerfo J (2004). Older adult perspectives on physical activity and exercise: voices from multiple cultures. Preventing Chronic Disease 1, A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundy A, Freeman P, Stubbs B, Probst M, Coffee P, Vancampfort D (2014a). The transcending benefits of physical activity for individuals with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Psychiatry Research 220, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundy A, Freeman P, Stubbs B, Probst M, Vancampfort D (2014b). The value of social support to encourage people with schizophrenia to engage in physical activity: an international insight from specialist mental health physiotherapists. Journal of Mental Health 23, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundy A, Stubbs B, Probst M, Hemmings L, Vancampfort D (2014c). Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity among persons with schizophrenia: a survey of physical therapists. Psychiatric Services 65, 693–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StatsDirect L (2005). StatsDirect Statistical Software. StatsDirect: UK. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Gaughran F, Veronesse N, Williams J, Craig T, Yung AR, Vancampfort D (2016a). How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophrenia Research. Published online: 31 May 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Richards J, Soundy A, Veronese N, Solmi M, Schuch FB (2016c). Dropout from exercise randomized controlled trials among people with depression: a meta-analysis and meta regression. Journal of Affective Disorders 190, 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs B, Williams J, Gaughran F, Craig T (2016b). How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research 171, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetani S, Waterreus A, Morgan V, Foley D, Galletly C, Badcock J, Watts G, McKinnon A, Castle D, Saha S (2016). Correlates of physical activity in people living with psychotic illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia LG, Kopeski LM, Mulrooney C, Reid J, Jacob K, Neuhaus EC (2009). Does exercise impact mood? Exercise patterns of patients in a psychiatric partial hospital program. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 15, 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher M (2007). Physical activity preferences and perceived barriers to activity among persons with severe mental illness in the United Kingdom. Psychiatric Services 58, 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Probst M, Sienaert P, Wyckaert S, De Herdt A, Knapen J, De Wachter D, De Hert M (2013b). A review of physical activity correlates in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 145, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Sweers K, De Herdt A, Detraux J, Probst M (2013a). Diabetes, physical activity participation and exercise capacity in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 67, 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch F, Rosenbaum S, De Hert M, Mugisha J, Probst M, Stubbs B (2016a). Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 201, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, Scheewe T, Remans S, De Hert M (2012). A systematic review of correlates of physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 125, 352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Probst M, Soundy A, Mitchell A, De Hert M, Stubbs B (2015a). Promotion of cardiorespiratory fitness in schizophrenia: a clinical overview and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 132, 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Schuch FB, Ward PB, Probst M, Stubbs B (2015c). Prevalence and predictors of treatment dropout from physical activity interventions in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. Published online: 2 December 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Schuch FB, Ward PB, Richards J, Mugisha J, Probst M, Stubbs B (2016b). Cardio-respiratory fitness in severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, De Hert M, Wampers M, Ward PB, Rosenbaum S, Correll CU (2015b). Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 14, 339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M, White D, Druss B (2015). A meta-review of lifestyle interventions for cardiovascular risk factors in the general medical population: lessons for individuals with serious mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 76, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynaden D, Barr L, Omari O, Fulton A (2012). Evaluation of service users’ experiences of participating in an exercise programme at the Western Australian State Forensic Mental Health Services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 21, 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001732.

click here to view supplementary material