Abstract

Background:

Researchers have gained substantial insight into mechanisms of synaptic transmission, hyperexcitability, excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration within the last decades. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are of central relevance in these processes. In particular, they are key elements in the etiopathogenesis of numerous seizure types and epilepsies. Earlier studies predominantly targeted on Cav2.1 P/Q-type and Cav3.2 T-type Ca2+ channels relevant for absence epileptogenesis. Recent findings bring other channels entities more into focus such as the Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channel which exhibits an intriguing role in ictogenesis and seizure propagation. Cav2.3 R-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC) emerged to be important factors in the pathogenesis of absence epilepsy, human juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), and cellular epileptiform activity, e.g. in CA1 neurons. They also serve as potential target for various antiepileptic drugs, such as lamotrigine and topiramate.

Objective:

This review provides a summary of structure, function and pharmacology of VGCCs and their fundamental role in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. We elaborate the unique modulatory properties of Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channels and point to recent findings in the proictogenic and proneuroapoptotic role of Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs in generalized convulsive tonic–clonic and complex-partial hippocampal seizures and its role in non-convulsive absence like seizure activity.

Conclusion:

Development of novel Cav2.3 specific modulators can be effective in the pharmacological treatment of epilepsies and other neurological disorders.

Keywords: Absence epilepsy, Afterdepolarisation, Ictal discharges, Low-threshold Ca2+ spike, Plateau potentials, R-type, Seizure

STRUCTURE, FUNCTION AND PHARMACOLOGY OF VOLTAGE-GATED Ca2+ CHANNELS

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) are of central relevance in mediating Ca2+ influx into living cells. They can trigger numerous physiological processes such as excitation-contraction coupling [1, 2], excitation-secretion coupling [3], hormone and transmitter release [4-6] and regulation of gene expression [7, 8]. From a structural point of view, VGCCs are heteromultimeric complexes built up of a central pore-forming, ion-conducting Cav-α1 subunit and various auxiliary subunits (α2δ1-4, β1-4 and γ1-8) (Fig. 1). Ten different Cav-α1 subunits have been characterized which can be classified based on their electrophysiological and pharmacological properties into high-voltage activated (HVA) and low-voltage activated (LVA) Ca2+ channels. HVA Ca2+ channels are further grouped into dihydropyridine (DHP)-sensitive L (“long-lasting”)-type Cav1.1–1.4 and non-L-type Cav2.1–2.3 channels which are less DHP-sensitive. The LVA T-(“transient/tiny”) type Ca2+ channels include Cav3.1-3.3 [4, 9, 10]. The latter channels are characterized by rather negative membrane potential activation threshold, a fast inactivation, and small single-channel conductance [10]. By contrast, HVA L- and non-L-type channels require much stronger depolarization to reach activation threshold [11], exhibit higher single-channel conductances, and show prolonged-channel opening in comparison to T-type channels [4, 12]. However, Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels were reported to exhibit mid-voltage activating characteristics under special physiological and electrophysiological conditions [12-15]. Pharmacodynamically, HVA L-type Ca2+-channels are highly sensitive towards DHPs (e.g. nifedipine), phenylalkylamines (e.g. verapamil, gallopamil, devapamil) and benzothiazepines (e.g. diltiazem) [14, 16-18]. Recently, ω-TRTX-Cc1a, derived from the venom of the tarantula Citharischius crawshayi (now Pelinobius muticus), turned out to be a potent and selective blocker of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels [19]. Experimental activators of L-type channels include BayK8644, FPL64176, PCA50941 and SZ(+)-(S)-202-791, none of which is however used in clinical application settings [20].

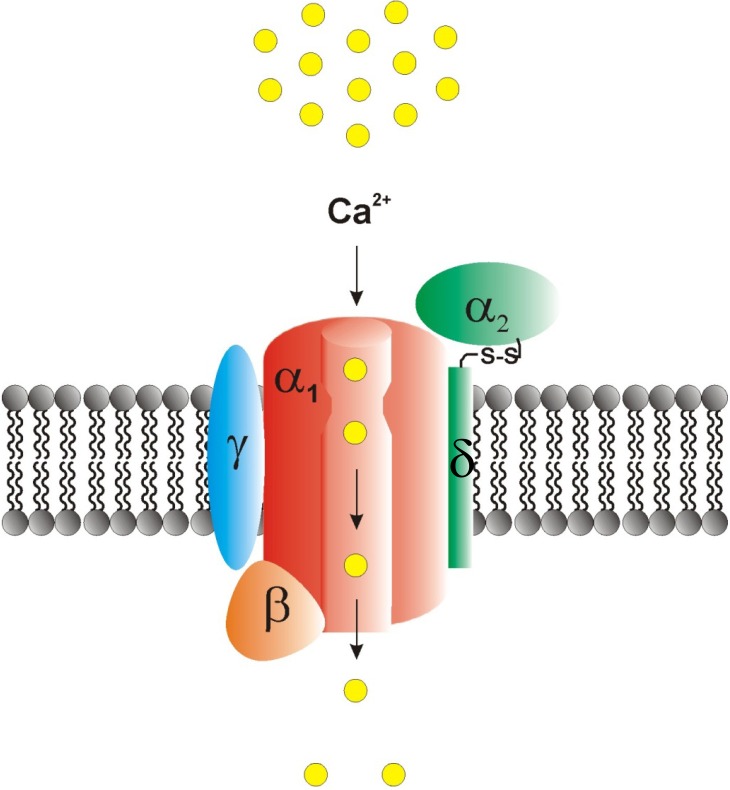

Fig. (1).

Structural buildup of voltage-gated Ca2+ channel complexes. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are composed of a central pore-forming and ion-conducting α1 subunit as well a variable subset of auxiliary subunits, including α2δ, β and γ-subunits. The β-subunit is located intracellularly whereas the γ and δ subunits are placed within the plasma membrane. The α2 subunit is covalently bound to the δ subunit via a disulfide bond and localized extracellularly. Both the Cav-α1 subunits as well as the auxiliary subunits are important drug targets (reprinted from [68]).

Synaptic transmission throughout the CNS is strongly dependent on presynaptic Ca2+ influx through the Cav2.1-Cav2.3 VGCCs. In addition to triggering exocytosis, Ca2+ influx also mediates complex patterns of short-term synaptic plasticity. The different Cav2 VGCCs vary in their functional coupling to synaptic transmission over different frequency ranges. This has tremendous impact on the frequency tuning of presynaptic neuromodulation and synaptic dynamics [21]. HVA Cav2 non-L-type Ca2+ channels which are predominately engaged in synaptic transmission in the brain are effectively inhibited by various peptide snail and spider toxins. Omega (ω)-agatoxin IVA, derived from the funnel web spider Agelenopsis aperta preferentially targets Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels. Other Cav2.1 blockers include ω-agatoxin IIIA, ω-agatoxin IVB, peptide toxins from the venom of the marine snail Conus geographus, i.e. ω-conotoxin MVIID, ω-conotoxin CVIB, ω-conotoxin CVIC, the spider toxin ω-phonetoxin IIA derived from Phoneutria nigriventer, DW13.3 extracted from the venom of the spider Filistata hibernalis and the scorpion venom toxin Kurtoxin [20, 22-24]. Though widely used in basic science, none of these blockers has reached clinical application so far. Omega (ω)-conotoxin GVIA derived from Conus geographus preferentially blocks Cav2.2 Ca2+ channels. Further Cav2.2 Ca2+ channels blockers are ω-conotoxin MVIIA, ω-conotoxin CVIA, ω-conotoxin CVIB; ω-conotoxin CVIC, ω-conotoxin CVID, ω-conotoxin SO-3, DW 13.3 and Huwentoxin HWTX I [23-25]. Omega (ω)-conotoxin MVIIC, a toxin from the venom gland of the marine snail Conus magnus, targets both Cav2.1 and Cav2.2 Ca2+ channels [4, 26-30]. In contrary, glycerotoxin from the venom of Glycera convoluta was shown to act as an activator of Cav2.2 Ca2+ channels [31]. Although most naturally derived peptide toxins are predominantly of experimental interest and not yet applicable in humans, Cav2.1-2.3 VGCCs turned out to serve more and more as potential targets in epilepsy, pain treatment and other neurological diseases. Gabapentin, for example, inhibits Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels via interaction with the α2δ auxiliary subunits (albeit non-selectively), and it can influence pain and epilepsy in humans [32]. Ziconotide (ω-conotoxin MVIIA, i.e. SNX-111), a toxin derived from the marine piscivorous snail Conus geographus, is likely to inhibit Cav2.2 Ca2+ channels and is a potent drug in humans who turned out to be refractory or non-tolerant to opioids [29, 30]. The GABAB receptor agonist baclofen can strongly inhibit Cav2.1 and Cav2.3 whereas c-Vc1.1, a cyclized version of the analgesic α-conotoxin Vc1.1 acting through GABAB receptors, did not affect Cav2.1 but severely inhibited Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels. These findings support the view that Vc1.1 inhibition of Cav2.3 VGCCs defines Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels as a potential target in analgesic treatment [33]. For the LVA Cav3 Ca2+ channels, a number of potential inhibitors have been evaluated, such as the tetraline derivative mibefradil and the scorpion toxin kurtoxin [34]. Other potential T-type Ca2+ channel blockers include Protoxin-I or β-theraphotoxin-Tp1a (ProTx-I), NNC55-0396, ML-218 and pimozide. Recently, azetidinones and spiro-azetidines have been described as novel potential blockers of the T-type Ca2+ channel Cav3.2 being of potential relevance for the treatment of neuropathic and inflammatory pain [35]. However, these potential T-type blockers have not reached clinical application so far. Diphenylalkylamine derivatives such as flunarizin or cinnarizin exhibit a non-specific blockade on VGCCs. Recently, new generation state-dependent T-type Ca2+ channel antagonists such as TTA-P2 and TTA-A2 have been described which seem to interfere preferentially with inactivated T-type Ca2+ channels [36]. Both state-dependent blockers exhibit analgesic effects in rodent models of pain. Z123212, a bi-targeting inhibitor of voltage-dependent Na+ channels and T-type Ca2+ channels exerts its analgesic effect by selectively targeting the slow inactivated state of the channels [37]. Notably, phase I clinical trials for the treatment of pain are currently performed for Z944, a state-dependent T-type channel inhibitor. Several pharmaceutical companies have focused their preclinical research on T-type Ca2+ channels inhibitors and activators and the future will reveal if clinical drugs finally emerge from these efforts. Importantly, LVA T-type Ca2+ channels are also sensitive to divalent heavy metal ions, such as Ni2+, Zn2+ or Cu2+ ions [4, 10]. Using a heterologous expression system, Cav1.2, Cav2.3 and Cav3.2 VGCCs were originally reported to be the most Zn2+ sensitive Ca2+ channels with IC50 values of 10.9 ± 3.4 μM, 31.8 ± 12.3 μM and 24.1 ± 1.9 μM, respectively [38]. Recently, it was also shown that Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 isoforms can serve as Zn2+ permeation routes mediating Zn2+ flux across the plasma membrane [39]. The functional relevance of this VGCC mediated Zn2+ flux related to Zn2+ transporter protein activity remains unclear.

Importantly, Zn2+ can exert distinct and partially opposite effects on Cav3.1-3.3 T-type Ca2+ channels [40]. Whereas Cav3.2 Ca2+ channels were blocked by submicromolar Zn2+ concentrations (IC50 = 0.78 ± 0.07 μM), Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 Ca2+ channels turned out to be less sensitive to Zn2+ (IC50 = 81.7 ± 9.1 μM and IC50 = 158.6 ± 13.2 μM, respectively). Hence, Zn2+ can be used for the pharmacological distinction of different T-type Ca2+ channels. On the electrophysiological level, different Zn2+ effects can be explained by subtype-specific modulation of Zn2+ acting on multiple binding sites of Ca2+ channels and altering their gating mechanisms. As a possible allosteric modulator of Ca2+ channels, Zn2+ is responsible for a shift to more negative potentials of the steady-state inactivation curves of Cav3.1-3.3 T-type Ca2+ channels and the steady-state activation curve of Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 Ca2+ channels [40]. Furthermore, inhibitory effects of Zn2+ are use-dependent and strongly suggest preferential Zn2+ binding to the resting state of T-type Ca2+ channels. Inactivation kinetics for Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 were significantly slowed, but not for Cav3.2 VGCCs. Deactivation kinetics of Cav3.3 Ca2+ channels were also significantly slowed upon Zn2+ exposure. However, Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 tail currents remained affected. An increased Cav3.3 mediated Ca2+ current was observed after Zn2+ application and resulted in increased duration of Cav3.3 mediated action potentials. Consequently, Zn2+ can apparently serve as an opener of Cav3.3 Ca2+ channel [40].

Within the last decade, Zn2+ emerged to be one of the most important heavy metal ions within the CNS, to the extent that is was sometimes referred to as “the calcium of the twenty-first century” [41]. Both divalent trace metals, Zn2+ and Cu2+, are implicated in a range of neurological disease states in humans that are characterized by alterations in neuronal excitability and/or neurodegeneration. Importantly, Zn2+ is known to exert significant effects on epileptic activity and excitotoxicity. However, the role of Zn2+ and Cu2+ in epilepsy and excitotoxicity is complex, and partially ambivalent. Whereas a number of studies illustrate that Zn2+ is a potential ionic mediator of selective neuronal injury [42-45], others provide strong evidence that Zn2+ is a powerful neuroprotector [41, 46-53]. Similarly, Zn2+ was reported to serve as both a proconvulsant [54] and anticonvulsant [55, 56] in humans and various animal models. These findings further support the apparent „Janus”-like behavior of Zn2+ ions in modulating neurodegeneration and seizure susceptibility. However, most of these prima facie contradictory observations described in the literature are based on differences in voltage- and ligand-gated ion channel expression within various neuronal cell types investigated, e.g. hippocampal interneurons versus pyramidal cells. Following KA-induced limbic seizures, hippocampal interneurons exhibit a dramatic increase in cytosolic Zn2+-concentration and cell death which is supposed to be due to mitochondrial dysfunction [44] and activation of specific Zn2+-signaling pathways [57]. Hippocampal interneurons were further reported to express Ca2+-permeable AMPA-receptors [58], and to release Zn2+ from mitochondria and other intracellular stores or metallothioneins [44]. Zn2+-levels turned out to be higher in interneurons compared to hippocampal pyramidal cells [59] due to differences in Ca2+-AMPA-receptor expression, Ca2+-buffering systems and differences in mitochondrial metabolism [60]. Compared to interneurons, CA3 pyramidal cells display only a moderate increase in internal Ca2+-levels after KA treatment [59]. Findings of Zn2+-release, intracellular Zn2+-accumulation and its effects on KA-seizure susceptibility and excitotoxicity are rather divergent as well. Whereas extracellular chelation of Zn2+ in one study neither affected hippocampal excitability nor seizure-induced cell death [61], studies by Takeda et al. illustrated that Zn2+ can clearly attenuate KA-induced limbic seizure activity and concomitant neurodegeneration in the CA3 region, or induce inverse effects, when being chelated extracellularly [46-53, 62]. Thus, by complex modulation of the inhibition - excitation balance involving VGCCs, Zn2+-homeostasis is crucial for both the induction of and the prevention of hyperexcitability-related seizure development and neurodegeneration. Most importantly, Zn2+ ions can exhibit not only different modulatory effects on numerous voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels such as VGCCs, but also enter cells via different channels including VGCCs, AMPA-, NMDA- and KA-receptors, particularly when neurons exhibit repetitive activation or hyperexcitability [41, 45, 63]. Thus, both Ca2+ and Zn2+ can serve as synaptic or transsynaptic second messengers with extracellular diffusion, e.g. spillover effects at mossy fibre terminals enabling complex heterosynaptic modulation. In line with these findings, synaptically released Zn2+ can effectively inhibit long-term potentiation (LTP) presynaptically at the mossy fiber synapse [64]. These findings directly corroborate the crucial role of HVA Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+channels, serving as a Zn2+ target in presynaptic LTP [38, 65, 66] as will be outlined below (Fig. 2).

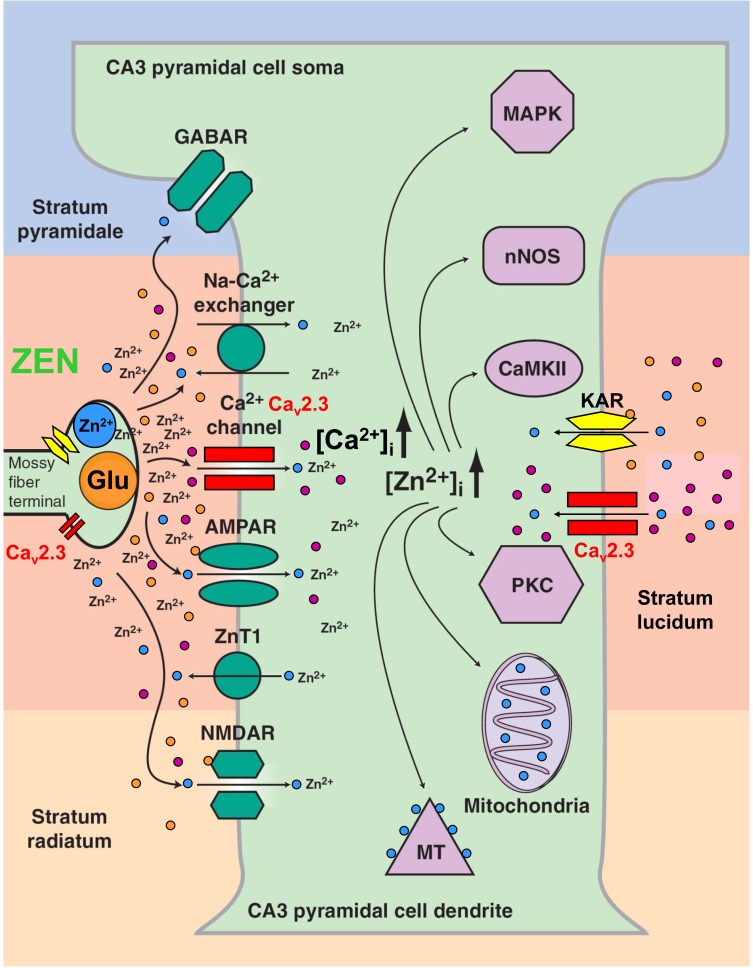

Fig. (2).

Functional interaction of divalent heavy metal ions (Zn2+) and various ion channels and transporters within the hippocampal CA3 region. Mossy fiber terminals carry both Zn2+ and glutamate containing vesicles. Upon presynaptic excitation, glutamate and zinc are released into the synaptic cleft. Zn2+ exerts numerous effects on AMPA and NMDA receptors, GABA receptors and transporters. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, particularly Cav2.3 VGCCs turned out to be of central relevance. Note that both Ca2+ and Zn2+ that enter the cell exert complex effects on intracellular signal transduction cascades (reprinted from [259]).

In drug research and development there is a strong need for new medical entities, i.e. first-in-class medicines that preferentially target individual Ca2+ channel entities. Arranz-Tagarro et al. [20] provided a summary of 23 patents in the period 2011-2013 claiming selectivity of newly synthesized compounds for HVA L- and N-type and LVA T-type Ca2+ channels. It’s noteworthy that indications of L-type blocker patents are mostly related to treatment of Parkinson’s disease but also cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. However, those blocking N- and T-type Ca2+ channels predominatly address neuropathic pain at the spinal cord, but also intractable pain of peripheral diabetic neuropathy, herpes, cancer, trigeminal neuralgia, migraine, post-surgery and inflammatory pain. Within the Cav3 T-type subfamily, a specific pharmaceutical focus has been on Cav3.2 Ca2+ channels. The most often claimed indication, particularly for T-type Ca2+ channels, is epilepsy. Pathophysiologically, some seizures and epilepsy entities share common neuronal circuitries with similar pathophysiological dysrhythmicity. As outlined below this holds true for the thalamocortical (TC)-corticothalamic circuitry which is essential for the generation of slow-wave-sleep (SWS). Aberrant network activity i.e. hyperoscillation within this circuitry can result in absence epilepsy. Thus, Ca2+ channel modulators targeting absence epilepsy might also be effective in the treatment of sleep disorders for example. A major drawback in the development of Ca2+ channel blockers is the wide distribution of various Ca2+ channel subtypes with similar molecular structure in the brain and peripheral tissues. This may give rise to intolerable side effects. Given the tremendous physiological implications of VGCCs, it is not surprising that numerous voltage-gated Ca2+-channelopathies have been identified so far [67, 68] (Table 1).

Table 1. Pharmacology and tissue distribution of VGCCs as well as related channelopthies (reprinted from [68]).

| Cav-α1 | Pharmacology | Tissue affected | Syndromes associated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cav1.1 Cav1.2 Cav1.3 Cav1.4 | Dihydropyridne, Benzothiazepine, Phenylalkylamine, TaiCatoxin, Calciseptine Calcicludine, FS-2 | skeletal musclesubiquitary ubiquitary retina | Hypokalemic periodic paralysis type 1 (HypoPP1), malignant hyperthermia type 5 (MHS5)Timothy syndrome (LQT8, epilepsy) Not known x-linked conginital stationary night blindness 2 (xCSNB2), X-linked cone-rod dystrophy type 3 (CORDX3) |

| Cav2.1 Cav2.2Cav2.3 | ω-Agatoxin IVA ω-Conotoxin GVIA SNX-482, Ni2+ | CNS CNS/PNS CNS/PNS | Absence-epilepsy, episodic ataxia type 2, spinocerebellar ataxia type 6, familial hemiplegic migraine, Lambert-Eaton myastenie-Syndrome Lambert-Eaton myastenie-syndrome Not known |

| Cav3.1 Cav3.2 Cav3.3 | Mibefradil, Kurtoxin, Ni2+ | CNS/PNS CNS/heart CNS | Not known Absence-epilepsy (CAE), Autism spectrum disorders (ASD)Not known |

Besides the pore-forming α1 subunits, it is noteworthy that the auxiliary subunits α2δ1-4, β1-4 and γ1-8 can substantially influence the basic electrophysiological and pharmacological characteristics as well as the plasma membrane translocation of the Cav-α1 subunits [6, 69] and might also serve as targets in future drug research and development.

The Cavβ3 subunit for example determines the plasma membrane density of the pore-forming Cav2.3 α1- subunit. Four leucine residues in Cavβ3 form a hydrophobic pocket surrounding key residues in the Cav2.3 α1-domain. This interaction seems to play an important role in conferring Cavβ-induced modulation of the protein density of Cav α1-subunits in Cav2 channels [70]. In this context, interaction partners of VGCCs turned out to be most relevant in drug discovery and development, particularly in the field of epilepsy. Recently, an exceptional study on quantitative proteomics of Cav2 channel nano-environments, using knockout-controlled multiepitope affinity purifications together with high-resolution quantitative mass spectroscopy was carried out to unravel the molecular players in local subcellular signalling [71]. About 200 proteins have been identified that clearly differ in abundance, stability of assembly and preference for the individual Cav2 subunits. These potential interaction partners included kinases and phosphatases, cytoskeleton proteins, enzymes, SNAREs, modulators and small GTPases, various G-protein coupled receptors, ion channels and transporters, adaptors, extracellular matrix proteins, cytomatrix components, protein trafficking components and additional proteins of yet unknown function.

Ca2+ CHANNELS IN ICTOGENESIS AND EPILEPTOGENESIS

Under physiological conditions, Ca2+ influx into functional neurons is organized in a complex fashion including amplitude, frequency and space as the spatiotemporally integrated free cytosolic Ca2+ concentration encodes specific information [72]. In general, cytosolic Ca2+ increase is mediated via release from intracellular Ca2+ stores, such as the endoplasmatic and sarcoplasmatic reticulum, via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, VGCCs and an armamentarium of other, often less-specific voltage- and ligand gated cation channels. VGCCs effectively couple complex neural activation patterns to cytosolic Ca2+ influx. Until internal Ca2+buffering procedures restore the resting intracellular Ca2+ levels [73, 74], the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration triggers crucial cellular functions, e.g. channel modulation, release of neurotransmitters and gene transcription. The Ca2+ influx via VGCCs is supposed to be of central relevance in hyperexcitability and excitotoxicity mediated neurodegeneration. For example, the so called Ca2+ hypothesis of epileptogenesis proposes that altered cytosolic Ca2+ levels may play a critical role in ictogenesis and epileptogenesis [75-78]. Both HVA and LVA Ca2+ channels are predominant mediators of internal Ca2+ elevation during most epileptiform activity [75, 79]. In hippocampal neurons it has been reported that the density of Ca2+ current was up-regulated during ictogenesis / epileptogenesis [80] and inhibition of VGCCs substantially depressed epileptiform activity [81, 82]. On the cellular electrophysiological level, Ca2+ channels were proven to be of central importance in mediating potential ictiform / epileptiform activity, such as afterdepolarization (ADP), plateau potentials (PP) and exacerbation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (LTCS) / rebound burst firing thus mediating seizure initiation, propagation and kindling [34, 83-86]. In addition, VGCCs exert major effects in excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration contributing to the devastating pathophysiology of human neuronal diseases associated with neurodegeneration [87-89]. Therefore, pharmacological modulation of VGCCs is a promising approach in functional interference with seizure activity, excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration [90-96]. As outlined below, many studies regarding the involvement of VGCCs in ictogenesis and epileptogenesis were carried out on HVA Cav2.1 and LVA Cav3 type Ca2+ channels. However, within the last years, a specific focus has been on the unexpected role of Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs in the field of epilepsy.

WHAT MAKES Cav2.3 R-TYPE Ca2+ CHANNELS SPECIAL?

The Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channel exhibits a complex histological and cellular distribution pattern with Cav2.3 being expressed in the peripheral and central nervous system (CNS), the endocrine [97, 98], cardiovascular [99-101], reproductive [102-105], and gastrointestinal system [106]. Additionally, Cav2.3 is of central relevance in the developing lung [107] and sensing organs such as the inner ear and organ of Corti [108]. In the last 15 years researchers have gained tremendous insight into the functional role of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels based on the generation of Cav2.3 deficient mice. Within the CNS, Cav2.3 VGCCs are involved in presynaptic / postsynaptic plasticity and neurotransmitter release [65, 66]. Additionally, Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels were shown to be engaged in the control of pain behavior [109], the physiology of fear [110] and myelinogenesis [111]. Interestingly, Cav2.3 VGCCs are also involved in the semaphorin 3A mediated conversion of axons to dendrites and the control of neuronal identity during nervous system development [112]. Furthermore, Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels seem to exhibit a protective function in ischemic neuronal injury [113] and contribute to vasospasms following subarachnoid hemorrage in humans [114]. Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs were also thought to play a crucial role in mediating analgesic opioid effects and underlying pain pathways. Although it remains unknown to a large extend whether single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the human CACNA1E gene encoding Cav2.3 VGCCs affect the analgesic effects of opioids, there is increasing evidence of a link between CACNA1E gene polymorphisms and fentanyl sensitivity [115]. Besides Cav1.2, the Cav2.3 VGCC is also expressed in colonic primary sensory neurons and was reported to be of major importance in visceral inflammatory hyperalgesia [116]. Inhibition of Cav2.3 VGCCs by eugenol was also shown to contribute to its analgesic effect [117]. The expression of Cav2.3e as the main R-type VGCC isoform in nociceptive DRG neurons also points to a potential target for pain treatment, e.g. in the trigeminal and spinal cord system [118, 119]. Furthermore, Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels were detected in small to medium muscle afferent neurons revealing the following expression pattern: Cav2.2 > Cav2.1 ≥ Cav2.3 > Cav1.2 channels [120]. Notably, Cav2.3 VGCC are dominantly expressed presynaptically, e.g. in mossy fibers of the hippocampus [121] and the pallidal globe [122], besides Cav2.1 [123] and Cav2.2 [124] and it is also expressed at the neuromuscular junction [125]. At the presynaptic site, a minor fraction of Cav2.3 VGCCs is are localized to the active zone of the vesicle fusion machinery and thus functionally contributes to neurotransmission [123]. A dominant fraction however, is localized more peripheral in the synapse responsible for synaptic plasticity, e.g. long-term potentiation (LTP) [66]. In addition, it should be noted that Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs are homogenously expressed on the cell soma and the dendritic arbor. The dendritic expression pattern is highly complex and only present in certain CNS nuclei and specific cell types, such as CA1 neurons. The highly organized spatial distribution pattern of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels with predominant expression in the proximal or distal dendrites clearly differs from other HVA VGCCs [126]. Functionally, Cav2.3 was reported to underlie the generation of Ca2+-dependent APs. The latter are conducted along the ramified dendritic arbor which serves an important entry site of Ca2+ and crucial factor in neural electrogenesis [127]. This characteristic somatatodendritic function of Cav2.3 VGCCs is likely to be involved in a number of characteristic ictiform / epileptiform electrical phenomena. Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channels were considered to be unique as they turned out to be resistant to most Ca2+ channel blockers. In 1998 however, the spider peptide toxin SNX-482, derived from the venom of the tarantula Hysterocrates gigas (homologous to the spider peptides grammatoxin S1A and hanatoxin), was demonstrated to be a selective Cav2.3 Ca2+ channel antagonist at low nanomolar concentrations (IC50 = 15-30 nM) [128]. Recently however it turned out that SNX-482 also dramatically reduces A-type K+ currents in mouse dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra pars compacta. Patch-clamp studies on Kv4.3 stably transfected HEK293 cells revealed an IC50 < 3nM which indicates a substantially higher potency than for SNX-482 inhibition of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels [129]. Thus, caution has to be exercised when interpreting SNX-482 antagonistic effects on cells and neural circuits where these channels are actually expressed. Cav2.3 blocking effects were also reported for DW 13.3, the Phoneutria (Ctenus) nigriventer (Brazil armed spider) toxin ω-ctenitoxin-Pn2a including ω-PnTx3-3, ω-PnTx3-6 and ω-phonetoxin IIA [20]. In addition, Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels exhibit high sensitivity to divalent heavy metal ion such as Ni2+ (IC50 = 27 μM), a property that they share with Cav3.2 Ca2+ T-type channels (IC50 = 5-10 μm [130],). Furthermore, in vitro dose-concentration studies using the HEK 293 heterologous expression system and calibrated heavy metal ion concentrations revealed that Cav2.3 is a most sensitive target of Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions with IC50 values of 1.3 ± 0.2 μM and IC50 = 18.2 ± 3.7 nM, respectively, using voltage steps to -20 mV representative for effects on activation gating. In the same setting IC50 values of 8.1 ± 1.4 μM for Zn2+ and 269 ± 101 nM for Cu2+ representative for action on conductance with voltage steps to +20 mV were obtained [131]. This clearly differs from other ion channels and receptors, e.g. NMDAR (IC50 = 270 nM) and Cav3.2 (IC50 = 900 nM) [132, 133]. Abolishing the effects on potential binding sites of divalent heavy metal ions by chelation or by substitution of key amino acid residues in the IS1–IS2 (H111) and IS3–IS4 (H179 and H183) loops substantially enhanced Cav2.3 mediated Ca2+ influx. This is mediated by a shift in the voltage-dependence of activation towards more negative membrane potentials [131]. The authors further demonstrated that Cu2+ modulates the voltage dependence of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels by affecting gating charge movements. The presence of Cu2+ ions resulted in a delay in activation gating and a reduction of voltage sensitivity of the channel. It was further shown that neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and glycine can serve as trace metal chelators per se and thus substantially regulate activity of Cav2.3 VGCCs by modulating their voltage-dependent gating. Interestingly, glutamate substantially potentiated the activity of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels at hyperpolarized potentials by shifting their voltage-dependent activation curve towards more negative voltages. Most importantly, the glutamate effect on Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels was clearly based on the chelating effect and mechanistically distinct from the activation of intracellular signal transduction cascades [134]. Glutamate effects on Cav2.3 are exerted from the extracellular space and although the trace metal binding character has been documented before [135] it was not considered to be physiologically relevant until now. Importantly, it has never been mentioned before that trace amounts of divalent heavy metals that often contaminate external solutions [130, 136] can exert tonic antagonistic effects on Cav2.3 voltage-dependent gating. Due to the observed shifts in IV-curves and changes in current kinetics in the presence of various Zn2+ and Cu2+ concentrations, Cav2.3 VGCC turned out to be mid-voltage activated in a Zn2+ and Cu2+ low/free environment. It has been estimated that an average HEPES–TEA solution contains about 50 nM Cu2+, which can result in a 17 mV negative shift in the Cav2.3 Ca2+ activation curve. In addition, trace metal chelation also enhanced Cav2.3 Ca2+ current inactivation kinetics [131]. These findings are likely to have a severe impact on our view on Cav2.3 VGCCs and require a thorough re-assessment of previously reported electrophysiological studies on Cav2.3 VGCCs. Additionally, they demonstrate that basic electrophysiological properties of VGCCs can be modulated by local changes in environmental cell conditions and that a plethora of new (patho) for the Cav2.3 VGCC entity (Fig. 2). It should further be noted that extracellular acidification can decrease Ca2+ current amplitude and results in a depolarizing shift in the activation potential (Va) of VGCCs. These effects hold true for all VGCC including Cav2.3, but differences occur between individual VGCC entities and the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Alterations of Ca2+ current amplitude effectuated by extracellular acidification or alkalinisation were shown to be of higher importance for Cav2.3 R type VGCCs than for Cav2.1 P/Q-type channels for example [137].

MODULATION OF Cav2.3 VGCCS VIA DIFFERENT RECEPTORS AND SIGNALING CASCADES

A number of Cav2.3 splice variants have been described [138] and this diversity is likely to be potentiated by co-assembly with different auxiliary subunits such as α2δ, β, and γ. The Cav2.3 VGCC is modulated biochemically by interconversion, i.e. phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. These two processes are of central relevance as they can alter fundamental electrophysiological properties of the channel and are related to the induction and perseveration of epileptiform burst activity in neurons [139] as outlined below. Interestingly, Cav2.3 VGCCs are automodulated in a bidirectional manner depending on the Ca2+ influx via Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channels. If cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations are low, Cav2.3 activation via protein kinase C (PKC) slows down the inactivation kinetics and enhances recovery from short-term inactivation [140, 141]. This mechanism represents a positive feedback based on the presence of exon 19 that represents an arginine rich insert 1 in the cytosolic II–III loop [138]. In consequence, Cav2.3e R-type Ca2+ channels lacking exon 19 encoded insert 1, exhibit only residual phorbol ester mediated stimulation which is however still significant. This view is supported by the observation that coexpression of PKCα with Cav2.3e results in similar kinetics of inactivation and recovery as obtained for the full length II–III loop splice variant Cav2.3d. These findings suggest that the expression pattern of Cav2.3 splice variants in different brain regions is of significant relevance for neuronal mechanisms underlying neuroprotection, icto-/epileptogenesis and seizure propagation [94]. Importantly, a positive feedback mechanism by Ca2+ influx was also reported for L-type Ca2+ channels and is mediated through Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II [142]. At elevated cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations however, a prominent Ca2+-dependent inactivation renders the channel activity to further increase [143]. PKC-mediated protein phosphorylation is of major physiological relevance, mediating intracellular messengers and hormonal effects. VGCCs serve as effectors in numerous regulatory neurotransmitter and hormonal pathways initiated by G-proteins. This G-protein mediated regulation of VGCCs can either be indirect via second messengers and/or protein kinases or direct via physical interaction between G-protein subunits and the Cav α1-subunit. Functional studies elicited that G-protein interaction reversibly inhibits neuronal non-L type Ca2+-channels. Peak current amplitude is reduced and activation kinetics is slowed. The effects of the hetereotrimeric G-proteins on VGCC are well described for the Gβγ dimer [144, 145], whereas the role of Gα is yet not well understood. There is strong evidence that Gβγ directly interacts with the I–II linker of the Cav α1-subunit [146, 147]. Furthermore, the N-terminus of Cav2 α1 subunits also seems to be involved in G-protein coupled modulation [148] including Cav2.3. The Gβγ interaction site within the I–II linker partially overlaps the AID (α1-interacting domain) where β subunits bind. This observation suggests a physical competition between the agonistic β-subunits [148, 149] and the antagonistic effects of Gβγ [150]. Interestingly, it turned out that Gβγ exhibits inhibitory effects on LVA Cav3 T-type Ca2+-channels via interaction with the II–III-loop [151]. There are further hints of a sophisticated interdependence between G-protein pathways and PKC as activation of PKC antagonizes adjacent receptor-mediated G-protein inhibition of VGCC [147, 152]. Accumulation of internal Ca2+ at low concentrations leads to tonic activation of Cav2.3d resulting in enhanced responses, i.e. slowed inactivation and accelerated recovery from inactivation [140]. It has been reported by Dietrich et al. [66] that Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels contribute selectively to the so-called residual internal Ca2+ concentration which is essential for various forms of synaptic plasticity, but contributes less to the release of neurotransmitters. However, this residual internal Ca2+ can reach concentration of up to 0.5 mM [153, 154] and is capable of facilitating Ca2+ currents through Cav2.3d channels [140]. A positive feedback mechanism based on PKC activation might later be attenuated by negative feedback involving the N-lobe calmodulin-dependent modulation [143] and therefore help to maintain physiological internal Ca2+ concentrations. The PKC mediated modulation is one final step in the muscarinergic signal transduction cascade. It had been described earlier that Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels when expressed in HEK cells with M2 muscarinic receptors, exhibit a biphasic modulation [155-157]. Muscarinic inhibition of Cav2.3 VGCCs is mediated by Gβγ subunits, whereas stimulation is mediated by pertussis toxin-insensitive Gα subunits [158]. These authors compared the modulation of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels by the three Gα/11-coupled muscarinic receptors M1, M3 and M5, revealing that these receptors trigger comparable stimulation of Cav2.3 channels. The signaling pathway that mediates stimulation was analyzed for M1 receptors in detail indicating that muscarinic stimulation of Cav2.3 involves signaling by Gα/11, diacylglycerol (DAC), and a Ca2+-independent PKC. In contrast to stimulation, the Gβγ mediated magnitude of Cav2.3 inhibition depended on the receptor subtype, with M3 and M5 receptors producing larger Cav2.3 inhibition than M1 receptors. Interestingly, muscarinic inhibition of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels was notably enhanced during pharmacological suppression of PKC, suggesting the presence of cross-talk between Gβγ-mediated inhibition and PKC-mediated stimulation of Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channels similar to what has been described previously for N-type channels. The role of muscarinic modulation of Cav2.3 VGCCs in ictogenesis and seizure activity will be discussed below. It should be noted that Cav2.3 is also substantially regulated by small GTPase RhoA [159] and it was speculated that this might influence synaptic transmission during brain development and contribute to pathophysiological processes when axon regeneration and growth cone kinetics are impaired [159].

Cav2.3 TYPE VGCCS IN CONVULSIVE SEIZURE ACTIVITY

Aberrant burst activity is a typical feature of neuronal epileptiform activity. Each cellular burst is based on a slow, persistent depolarization, the so-called PP [160] which can last up to seconds [161, 162]. A PP is regenerative, spike dependent and is mediated by the summation of depolarizing APs [163, 164]. In addition, internal Ca2+ levels attain a plateau that is typically 4200 nM above rest and reached after several seconds of activity. However, the PP generally collapses soon, once the electrical activity has ceased and the membrane repolarizes again [163, 164]. As regards PP termination, it has been suggested that an increase of internal Ca2+ and the subsequent activation of a Ca2+-dependent K+-mediated afterhyperpolarisation (AHP) might account for this phenomenon [165, 166]. Besides, a shift from Ca2+-dependent facilitation to Ca2+ dependent inactivation of VGCCs with increased internal Ca2+ levels might also be involved. Generally, PPs and ADP are common electrophysiological phenomena in different neuronal cell entities in different brain regions such as spinal and brainstem motor neurons, spinal interneurons, dorsal horn neurons, subicular and entorhinal cortical cells, subthalamic nucleus neurons, suprachiasmatic neurons, striatal cholinergic neurons and hippocampal pyramidal cells [167]. Nevertheless, the entire voltage- and ligand-gated ion channel armamentarium underlying PP and ADP generation is still not fully understood. Recent studies more and more suggest that Cav2.3 VGCCs are potent players in PP and ADP generation thus serving an important role in ictogensis [168-175].

Importantly, one has to consider that these data were recorded from various tissue preparations from different species and that dihydropyridines involved in these studies exert complex action on VGCCs. Experimental conditions, such as neuronal membrane potential or penetration depth of various VGCC blockers in CNS slices can severely modulate electrophysiological results [176-178].

Various neurological and cardiovascular studies have suggested that Cav1.3 could mediate both a low-threshold and low-dihydropyridine sensitive L-type Ca2+ current [12, 15]. In consequence, Cav1.3 was speculated to be involved in PP generation in different neuronal cell types. Whereas the electrophysiological behavior of LVA Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels has been described recently [12, 14], Cav2.3 had already been known to exhibit low- to mid-voltage activated activity based on both activation and steady-state inactivation kinetics prominent at relatively negative membrane potentials [99, 167, 179-183]. In addition, Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channels were shown to contribute to sustained PPs and ADPs in hippocampal CA1 neurons with the latter known to enhance neural excitability and epileptogenicity [85, 184]. Studies by Fraser and MacVicar [185] and Fraser et al. [186] demonstrated that carbachol mediated cholinergic stimulation of CA1 neurons causes slow ADP and long lasting PP both of which resemble epileptiform activity. In general, activation of the cholinergic system is a well-known approach to induce limbic seizures both in vitro and in vivo [187-190]. Importantly, PPs are important electrophysiological phenomena in ictogenesis mediated by Ca2+ influx through VGCCs. They are modulated upon muscarinic receptor activation and mediate activation of guanylate cyclase activity and subsequent increase in cGMP [191] (Fig. 3). Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs were proven to be responsible for Ca2+ influx in dendritic spines, e.g. of CA1 neurons [192] and it was further depicted that a reduction of R-type Ca2+ current reduces the accumulation of postsynaptic [Ca2+]i, particularly following recurrent synaptic activation [193, 194]. Notably, stimulation of metabotropic muscarinic receptors via carbachol for example results in inhibition of L-, N-, and P/Q-type VGCCs [195-197]. In contrast, R-type Ca2+ current is significantly enhanced [198-200]. Topiramate, an AED drug that was shown to block carbachol-induced PPs in subicular bursting cells [201] was used by Kuzmiski et al. [85] to directly prove that topiramate can dampen the generation of PPs by inhibiting R-type VGCCs. Pharmacodynamically, topiramate has a multi-target character interacting with, e.g. voltage-gated sodium channels, VGCCs and AMPA/kainite receptors or GABA(A) receptors [85, 202]. Kuzmiski et al. [85] utilized Cav2.3 expressing tsA-201 cells that were co-transfected with β1b and α2δ auxiliary subunits to demonstrate that topiramate can block Cav2.3 mediated Ca2+ currents at therapeutically relevant concentrations. Their studies revealed an IC50 of 50.9 µM and complex alterations in electrophysiological characteristics including a shift of the steady-state inactivation curve to more negative potentials. The Ca2+ spikes that were provoked in this study were transient and high-threshold activated. Following application of TTX and a cocktail of VGCC blockers (i.a. nifedipine 10 μM) to eliminate other current components, the remaining Ca2+ spike was based on R-type mediated Ca2+ current. The latter was increased upon carbachol administration concomitant to an enhanced spike frequency and decreased threshold of Cav2.3-mediated spiking. As expected, topiramate significantly reduced the R-type Ca2+ spike amplitude. Kuzmiski et al. [85] did not report on experiments to block R-type Ca2+ currents using SNX-482 [128] which serves as a rather selective blocker of Cav2.3 R-type channels. However, as outlined above the Cav2.3 Ca2+ channel selectivity of SNX-482 has recently been substantially challenged [129]. Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels were reported to contribute at around 80% to R-type Ca2+ current in CA1 neurons. Furthermore, the R-type component turned out to be sensitive to low Ni2+ concentrations (50 μM). Taking into account that 10 μM nifedipine can effectively block Cav2.3 VGCCs [99, 180] one might speculate that a realistic Cav2.3-mediated topiramate effect on carbachol-enhanced Ca2+ spiking is even more prominent. In the past, detailed studies were carried out to define the signal transduction cascade between muscarinic receptors and Cav2.3 VGCCs. Melliti et al. [155] and Bannister et al. [158] provided detailed insight how Cav2.3 VGCCs are modulated upon M1, M3 and M5 muscarinergic receptor stimulation. Importantly, all three muscarinic receptors can exert complex effects on Cav2.3 VGCCs. Whereas a pertussis toxin-insensitive Gαq/11 subunit, PLCβ, DAG and a Ca2+ independent PKC signal transduction mechanism mediates stimulation of Cav2.3, the Gβγ subunits exert inhibitory action on Cav2.3 VGCCs [203]. Moreover, M1/M3 muscarinic receptor activation was demonstrated to augment R-type, but not LVA T-type Ca2+ currents in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons following selective blockage of N-, P/Q-, and L-type Ca2+ currents [84]. Hippocampal pyramidal neurons are known to highly express postsynaptic M1 and M3 receptors [204, 205] which are Gαq/11 coupled. Activation of M1/M3 and attached G-proteins results in synthesis of DAG and IP3 following PLC activation. DAG can activate Ca2+-independent group II PKCs, most likely PKCδ [84]. This findings goes together with the observation that R-type Ca2+ currents are inhibited upon muscarinic receptor stimulation in CA1 neurons once PKC is inhibited. This phenomenon is due to the activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein-coupled M2/M4 receptors as well as Gβγ subunits [157, 158]. The hippocampal ictogenic potency of Cav2.3 VGCCs is also confirmed by the observation that mice lacking the M1 receptor display reduced seizure susceptibility following pilocarpine adminstration [206]. One should consider that etiopathogenetic mechanisms of ictogenesis and/or epileptogenesis can also include other voltage-dependent Ca2+ conductance as well [207]. During early stages of epileptogensis, Hendriksen et al. [208] observed a significant increase in Cav2.1, Cav1.3- and particularly Cav2.3 α1 mRNA levels in the hippocampal compared to control animals in an electrical stimulation model [208].

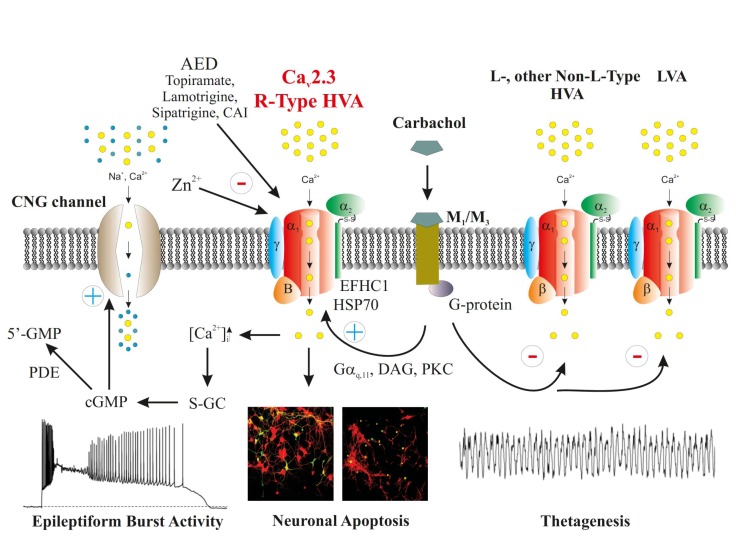

Fig. (3).

Functional implications of Cav2.3 R-type VGCC in cellular epileptiform activity, excitotoxicity and thetagenesis. Cav2.3 mediated Ca2+ influx triggers varies intracellular cascades. One cascade mediates the activation of cyclic-nucleotide gated channels leading to plateau potentials and superimposed bursting. Associated hyperexcitability and Ca2+ overload can result in excitotoxicity and neuronal apoptosis. Note that Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels are modulated by muscarinic signaling. The G αq11, DAG and PKC pathway was reported to be associated with thetagenesis as well (reprinted from [260]).

Within the last decade there has been an increasing number of reports that directly link VGCCs to specific epilepsy entities in humans as well. Indeed, a number of mutations within the ion-conducting Cavα1 subunits and the auxiliary subunits (β, α2δ, and γ) of VGCCs were shown to be involved in convulsive and non-convulsive seizure activities in humans. These include i.a. childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) or juvenile myoclonus epilepsy (JME). Mutations in the HVA Cav2.1 VGCC for example were detected in patients suffering from absence epilepsy, episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2), and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6). LVA T-type Ca2+ channels such as Cav3.2, were proven to be important in the etiology of CAE. In addition, they are important targets for a number of AEDs, e.g., suxinimides, lamotrigine (LTG) and zonisamide (ZNS). Although Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs are highly expressed in the central nervous system, Cav2.3 related epilepsy entities have rarely been reported. In one study, mutations in EFHC1, a C terminal interaction partner of Cav2.3 VGCCs, were shown to cause JME in humans. EFHC1 is known to induce neuronal apoptosis by functional interdependence with Cav2.3 and related mutations in EFHC1 were shown to disrupt C-terminal binding. Interestingly, the lack of apoptosis causes increased cell density and hyperexcitable neural circuits in affected patients. More in vivo data on Cav2.3 VGCCs in epileptogensis are available on the preclinical level. Electroencephalographic characterization of Cav2.3 deficient mice exhibited no indications of spontaneous epileptiform graphoelements. However, seizure susceptibility testing proved that Cav2.3 VGCCs can contribute to seizure initiation, propagation, termination, and kindling [92, 139, 209]. Pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-seizure susceptibility was reduced and seizure architecture exhibited severe alterations in Cav2.3-/- mice compared with control mice, supporting the proconvulsive action of Cav2.3 VGCC [94, 96]. Similar findings were also obtained in Cav2.3 deficient mice following kainic acid (KA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) administration [95]. It turned out that Cav2.3-/- mice are also less susceptible to hippocampal seizures compared to control animals and that Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels are not only involved in hippocampal ictogenesis but also complex rhythm generation in the septohippocampal network [210]. It was shown that Cav2.3 VGCCs contribute to the genesis of atropine-sensitive type II. Urethane-induced atropine-sensitive type II theta oscillations are induced by muscarinic signaling via Gαq/11, PLCβ1/4, InsP3, DAG and PKC (Fig. 3) [210]. Unlike PLC β1 deletion, ablation of Cav2.3 does not result in a total abolishment of type II theta oscillations. However, the temporal characteristics of theta distribution, i.e. theta architecture was significantly altered upon Cav2.3 deletion [210]. Thus, Cav2.3 VGCC are also of tremendous in relevance septohippocampal synchronization associated with theta oscillation [210].

Cav2.3 VGCCS IN NON-CONVULSIVE SEIZURE ACTIVITY

Behaviorally, typical absence epilepsy is the prototype of non-convulsive seizure activity. It is characterized by a sudden onset and termination of paroxysmal loss of consciousness that is accompanied by bilateral synchronous spike-wave discharges (SWD). The frequency of these SWD turned out to be species-specific [211]. It has been shown several years ago that the TC circuitry, particularly the contribution of the ventrobasal thalamus and the reticular thalamic nucleus (RTN) are functionally involved in the initiation and propagation of absence seizures [212]. In addition, also extrathalamocortical structures, e.g. the reticular formation, the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus, the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, the basal nucleus of Meynert, the raphe nuclei, the locus coeruleus and cerebellar structures are functionally connected to the TC circuitry. Interestingly, brain structures like hippocampus or cerebellum that are classically not known to be involved in the generation of absence SWDs in fact also participate in the development of the absence epilepsy phenotype [213]. On the pathophysiological level, TC dysrhythmia is assumed to be the substrate of SWDs. Electrophysiologically, thalamic relay neurons but also others have the unique capability to shift between different functional states, i.e. the tonic mode, the intermediate mode and the burst firing mode. These different modes strongly regulate transmission of external information to the cortex [214]. The tonic firing mode is typical of stages of high vigilance. When ascending activity originating from deeper brain structures decreases, thalamic relay neurons re- and hyperpolarize. They first exhibit the intermediate mode and finally display rebound burst firing. A number of voltage- and ligand-gated channels involved have been characterized including hyperpolarization and cyclic-nucleotide gated, non-specific cation channels (e.g. HCN2, HCN4) and LVA Cav3.1-3.3 T-type Ca2+ channels that can trigger LTCSs with superimposed bursts of conventional Na+/K+ APs. Rebound burst firing can be terminated by both voltage- and Ca2+- activated current entities, e.g., IA and IK(Ca2+). Rebound burst firing in the TC circuitry is characteristic of low vigilance as holds true for slow wave sleep (SWS). Furthermore, reinforced oscillatory activity accompanied with intensive rebound burst firing of RTN and thalamic relay neurons is of central importance in the etiopathogenesis of absence epilepsy. Within the TC network, oscillatory activity is substantially triggered and sustained by the RTN which helps to control information gating and transfer from the periphery over the thalamus to the cortex. The shell-shaped RTN is strategically placed lateral to the ventrobasal thalamic relay nucleus and exerts inhibitory GABAergic activity on RTN cells themselves as well as on thalamic relay neurons [212]. Interestingly, a number of single-mutation mouse models of absence epilepsy have been described most of which related to genetic ablation of VGCCs. This underlines the critical role of VGCCs in absence epileptogenesis. In particular, HVA Cav2.1 and Cav3 LVA T-type Ca2+ channels were proven to be of central relevance in this field. For example, the Cav3.1 VGCC knock-out mouse model was reported to display resistance to absence seizures and a lack of burst firing in TC relay neurons [215]. In addition, Cav3.1-/- mice exhibited altered sleep architecture and a clear lack of delta waves [216]. The Cav3.1 Ca2+ channel is strongly expressed within thalamic relay neurons. Results obtained from Cav3.1-/- mice strongly indicate that other VGCCs including Cav2.3 are also of functional relevance within the TC circuitry. In contrast to Cav3.1-/- mice, Cav2.1 deficient animals are susceptible to absence epilepsy characterized by typical SWDs and motoric arrest [217]. The ablation of the Cav2.1 P/Q-type VGCCs causes progressive ataxia and altered synaptic transmission in Cav2.1-/- transgenic mice. Amazingly, Cav3 T-type Ca2+ currents were increased in TC relay neurons obtained from these mice [218]. When Cav2.1-/-;Cav3.1-/- double knock-out mice were generated, mice did not exhibit spontaneous SWDs anymore and no T-type Ca2+ current in TC relay neurons could be detected [219]. Besides, Cav3.1 VGCCs might be involved in movement disorders such as paroxysmal dyskinesia and ataxia [220, 221]. Summing up, enhanced T-type Ca2+ currents in various cellular components of the TC network were shown to be a critical phenomenon in absence epileptogenesis although it does not seem to be a must [219]. Clearly, Cav3 T- and Cav2.1 P/Q-type VGCCs are not the only electrophysiological players within the TC circuitry. Gabaergic interneurons of the cortex and the RTN as well as extrathalamocortical structures were proven to express Cav2.3 VGCCs [96, 179, 222-225]. A lot of studies as regards the role of Cav2.3 VGCCs in absence epileptogenesis were carried out in Wistar Albino Glaxo rats (WAG/Rij) and Genetic Absence Epilepsy Rats from Strasbourg (GAERS). In the latter, increased T-type Ca2+ currents in reticular thalamic neurons have been reported [226] and subsequently also changes in Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 Ca2+ channel expression in related thalamic nuclei, i.e. the adult ventroposterior thalamic nuclei and the RTN, respectively [223]. Importantly, de Borman et al. [222] and Lakaye et al. [213] described a prominent decrease of Cav2.3 VGCC in two extrathalamocortical brain structures in GAERS, the brainstem and the cerebellum both of which project to the TC circuitry, capable of modulating its oscillatory activity [227-229]. In addition, the WAG/Rij rat model of absence epilepsy displays altered VGCC expression as well. Development of SWDs in WAG/Rij rats goes together with an enhanced expression of Cav2.1 VGCC in the RTN. Interestingly, van de Bovenkamp-Janssen et al. [224, 225] elicited that control rats showed elevated Cav2.3 VGCC expression in the RTN from 3 to 6 months of age. In contrast, WAG/Rij rats of the same age clearly lacked this increase in Cav2.3 expression concomitant with the first occurrence of SWDs. These observations are further supported pharmacologically. Lamotrigine is known to inhibit Cav2.3 VGCCs [230] and effectively suppressed not only SWDs in both GAERS and WAG/Rij rats [211, 231] but also TC burst activity in rat brain slices [232]. Still, the unique electrophysiological features and neuronal implications of Cav2.3 VGCC expression within RTN cells, GABAergic interneurons and various extrathalamocortical structures on TC oscillatory action are not yet fully understood. Initial investigation of absence seizure susceptibility in Cav2.3−/− mice elicited that Cav2.3 affects TC hyperoscillation and absence seizure architecture. In accordance to reports on the absence-preventive effect of Bay K8644-enhanced HVA Ca2+ currents, one might expected that HVA Non-L-type Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels might support the tonic mode of action [233]. Recently however, Zaman et al. [86, 234] demonstrated in vitro and in vivo that Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels and a Ca2+-activated K+ channel, i.e. SK2, can form a functional microdomain that mediates slow afterhyperpolarisations (sAHPs) in RTN neurons following LTCS. Interestingly, Cav2.3-mediated Ca2+ influx is capable of activating SK channels which results in re- and hyperpolarization of the cell membrane causing repriming of T-type Ca2+channels and activation of HCN channels [86]. Thus, Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels seem to actively promote and sustain rebound burst firing in RTN neurons. Using the in vitro brain slice approach, the application of a hyperpolarizing current triggered a LTCS with typical superimposed Na+ bursts in reticular thalamic neurons from Cav2.3−/− mice. Notably, any consecutive oscillatory burst activity was severely dampened and sAHP was clearly reduced. About 51% of HVA Ca2+ current in RTN neurons turned out to be sensitive to the tarantula toxin SNX-482 and could thus be attributed to Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels [86]. Furthermore, Cav2.3 mediated Ca2+ influx was shown to functionally interact with voltage-insensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels type 2 (SK2) which are engaged in the generation of Ca2+-dependent sAHP. Zaman et al. (2011) argued that T-type Ca2+ channels are not sufficient to mediate cytosolic Ca2+ levels that can actually trigger sAHP, the latter however is a prerequisite for repriming T-type Ca2+ channels and rebound bursting firing. Thus, Cav2.3−/− mice demonstrate impaired RTN oscillatory behavior and reduced absence seizure susceptibility. Electrophysiological data from the RTN of Cav2.3−/− mice clearly demonstrated an impairment of reticular thalamic bursting which was supposed to result in reduced SWD activity triggered by γ-hydroxybutyrate administration. Interestingly, this functional scenario of Cav2.3 mediated SK2 activation has previously been described in the CA1 region as part of a functional triad including NMDA-receptors, Cav2.3 VGCCs and SK2. Similar to RTN neurons, Cav2.3 VGCCs and SK2 channels induce AHPs that are likely to serve as a negative feedback mechanism in regulating synaptic activity and plasticity in dendritic spines in the CA1 region [192, 235-237] as well as in epileptogenicity [238].

Given the cellular electrophysiological findings and absence seizure study results from [86], one might speculate that SWS is reduced in Cav2.3-/- mice. However, we observed an opposite effect [239]. Our sleep study in Cav2.3-/- mice suggested that Cav2.3 VGCCs significantly modulate sleep parameters in rodents in a light-dark cycle dependent manner. Major changes were observed for both the quiet and active wake duration, the SWS1 duration and the total number of sleep episodes in Cav2.3 deficient mice. Importantly, the wake duration was decreased compared to controls with significant increase in SWS1. Sleep analysis further pointed to an alteration of sleep architecture in Cav2.3−/− mice based on changes in sleep stage transitions. The most severe changes were observed during the dark cycle. Importantly, urethane induced SWS administration clearly supported sleep scoring results from spontaneous 48-h sleep recordings. Interestingly, anesthetic sensitivities to propofol and halothane were shown to be decreased in Cav2.3−/− mice, which might be related to different pharmacodynamic profiles compared to urethane. Joksovic et al. [240] reported that presynaptic Cav2.3 R-type VGCCs support inhibitory GABAA transmission in RTN neurons and are inhibited by isoflurane. It is difficult to predict the consequences that an inhibition of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels and IPSCs in the RTN might have on TC rhythmicity. It was previously described that Cav2.3−/− mice exhibit a decrease in the duration of suppression episodes in the EEG following isoflurane anesthesia [240] which is in line with data from Zaman et al. [86]. In the last decade, the functional involvement of Cav3 T-type VGCCs in mouse sleep architecture has been investigated in detail, finally resulting in the Ca2+ channel model of TC rhythmicity. As outlined above, T-type VGCCs are differentially distributed throughout the thalamus. Cav3.1 T-type VGCCs are dominantly expressed in thalamic relay cells whereas Cav3.2 and Cav3.3 VGCCs are localized in RTN neurons. Gene ablation studies on Cav3.1−/− mice showed that lack of Cav3.1 mediated Ca2+ influx in thalamic relay cells results in lack of burst firing activity due to impaired LTCS activity. However, region specific, i.e., cortical, not thalamic Cav3.1 deletion did not result in altered sleep. These findings resulted in a complex model of Cav3.1 Ca2+ channels in regulating TC rhythmicity and sleep. Based on this model, ablation of Cav3.2 and/or Cav3.3 might result in a phenotype comparable to that of Cav3.1−/− mice. However, although effects of Cav3.3 ablation on sleep spindles have been described, we are still lacking detailed sleep analysis in Cav3.2 and Cav3.3 knock-out mice. The model might predict that ablation of Cav3.2 and Cav3.3 results in impaired SWS. However, it was recently reported from a patent application that pharmacological blockade of Cav3.2 VGCCs can result in enhanced rather than impaired sleep, the reason of which remains to be determined. Moreover, transition rates and sleep architecture were altered. The latter findings strongly suggest that interpretation of sleep architecture in transgenic mice cannot be limited to the TC network itself, or thalamic nuclei in specific but also has to include extrathalamocortical structures as well (see below).

Like Cav3.2 and Cav3.3, the Cav2.3 R-type Ca2+ channels are expressed in the RTN, but not thalamic relay neurons. In addition, Cav2.3 transcripts are present in cortical interneurons. Moreover, Cav2.3 VGCCs are expressed in a number of extra-thalamocortical structures, such as the mesopontine REM-NREM modulators (the locus coeruleus, the dorsal raphe nuclei, the pedunculopontine, and the laterodorsal tegmental nuclei), the diencephalic sleep onset controllers (hypothalamic nuclei including the ventrolateral/lateral preoptic region and the tuberomammillary basal forebrain), the cerebellum, the basal ganglia and the hippocampus [94, 96]. These structures are known to project to the TC circuitry and substantially modify its activity via different neuromodulators, e.g., noradrenalin, histamine, serotonin (5-HT), and acetylcholine [92, 211, 241]. Other important Cav2.3 expressing structures include the suprachiasmatic nucleus involved in the regulation of the circadian rhythm and also sleep architecture [242, 243] and the amygdala which is also involved in sleep regulation. It’s noteworthy that Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels are of major relevance in the amygdala physiology. Lee et al. [110] intensively studied the molecular and electrophysiological characteristics of R-type Ca2+ channels in central amygdala neurons proving that Cav2.3 underlies R-type Ca2+ currents in these cells. However, the functional consequences of Cav2.3 based R-type Ca2+ currents in specialized amygdala neurons, i.e. Wake-ON, REM-ON, and NREM-ON Ace neurons remain largely unknown. However, findings from sleep analysis in Cav2.3-/- mice clearly point to the fact that a valid model of TC rhythmicity needs to include input also from extrathalamocortical structures. In conclusion, there is strong evidence that Cav2.3 VGCCs play a primary role in SWS, the etiology and pathogenesis of absence epilepsy and SWD generation.

Cav2.3 R-TYPE VGCC CHANNEL MODULATION AND ITS CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES

VGCCs are important targets for numerous AEDs [139, 244, 245]. Most AEDs were shown to inhibit HVA or LVA Ca2+ channels others than Cav2.3 VGCCs. Based on the findings described above, there is striking evidence that Cav2.3 VGCCs can serve as targets in convulsive and non-convulsive seizure pharmacotherapy. Lamotrigine (LTG) for example is a multi-target AED for the treatment of typical absence seizures and the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome [246, 247]. Pharmacodynamically, it acts via inhibition of both voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels [248]. LTG targets Cav2.1 and Cav2.2 VGCCs [249, 250], but also Cav2.3 R-type and Cav3 T-type channels [230]. Interestingly, LTG inhibits R-type Ca2+ currents stronger than T-type currents. Thus, Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels seem to be involved in the anti-absence activity of LTG suggesting an important role of Cav2.3 VGCCs in the etiopathogenesis of absence epilepsy. LTG at a concentration of 10 μM is capable of inhibiting Cav2.3-α1 coexpressed with β3 by 30% when applying therapeutically relevant brain concentrations of 4–40 μM [230]. Contrarily, Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 T-type Ca2+ channels exhibited only minor sensitivity to LTG.

In addition, Lamotrigine (LTG) was shown to dampen transient cytosolic [Ca2+] in rat pyramidal neurons. This is of relevance as alterations in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis are known to play an important role in the genesis of epileptiform discharges. Inhibiting transient elevations in neuronal [Ca2+]i by Lamotrigine (LTG) correlates with its anticonvulsant efficacy and could thus prevent neurons from hyperexcitability and excitotoxicity [79]. Notably, sipatrigine or 202W92 can also inhibit Cav2.3 VGCCs with IC50 values of 10 μM which is within therapeutically relevant brain concentrations of 20–100 μM for sipatrigine and 56 μM for 202W92. Furthermore, both sipatrigine and 202W92 exhibited neuroprotective effects in various animal models of ischemia [251, 252] and displayed anticonvulsant efficacy in both genetically epilepsy-prone rats and DBA/2 audiogenic mice [230, 253]. Importantly, McNaughton et al. [254] have characterized other potential Cav2.3 blockers that might be relevant in antiepileptic treatment, i.e. carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. The latter include for example ethoxyzolamide, acetazolamide and dichlorphenamide. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have numerous clinical applications, e.g. induction of diuresis, ocular hypertension relief and treatment of altitude sickness [255, 256]. However, epidemiological approaches also suggest their efficacy in patients suffering from absence epilepsy [255]. Ethoxyzolamide inhibited Cav2.3 mediated R-type Ca2+ current by 66-74% at 10 μM. On the other hand, dichlorphenamide (10 μM) which is used for treatment of generalized epilepsies resulted in a 24-76% reduction of R-type current [254]. Importantly, topiramate, a standard AED nowadays shares structural similarities with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and indeed also exerts remaining inhibitory action on carbonic anhydrases. Topiramate had already been reported to inhibit L-type Ca2+ currents [257]. Recently however, it was also proven [85, 254] that topiramate severely inhibits Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels by 68-77% when applied at therapeutically relevant concentrations of 10 μM. Furthermore, Kuzmiski et al. [85] showed that topiramate can block PPs in hippocampal CA1 neurons due its inhibitory action on Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels. As outlined above, PPs are of significant relevance in promoting epileptiform burst activity. Thus, inhibition of Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels by topiramate is responsible for a reduction in repetitive neural firing, spontaneous epileptiform burst activity and recurrent seizures [258]. It’s noteworthy that many AEDs, e.g. topiramate or Lamotrigine (LTG) that were proven to block Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels are multi-target drugs acting on an armamentarium of voltage- and ligand- gated ion channels.

Given the functional involvement of Cav2.3 VGCCs in the etiopathogenesis of both convulsive and non-convulsive seizures but also sleep (patho)physiology, future development of highly specific Cav2.3 Ca2+ channels blockers will be of tremendous pharmacotherapeutic relevance and a benefit for patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Christina Ginkel (German Center for Neurodegnerative Diseases, DZNE), Dr. Michaela Möhring (DZNE) and Dr. Robert Stark (DZNE) for assistance in animal breeding and animal health care. This work was financially supported by the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM, Bonn, Germany).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AED

Anti-epileptic drugs

- ADP

Afterdepolarisation

- AHP

Afterhyperpolarisation

- AP

Action potential

- CNS

Central nervous system

- DHP

Dihydropyridine

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- ECoG

Electrocorticogram

- EMG

Electromyogram

- GAERS

Genetic Absence Epilepsy Rats from Strasbourg

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney

- HVA

High-voltage activated

- LVA

Low-voltage activated

- LTG

Lamotrigine

- KA

Kainic acid

- LTCS

Low-threshold Ca2+ spike

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartat

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PP

Plateau potential

- RTN

Reticular thalamic nucleus

- SK

Small conductance potassium channel

- SWD

Spike-wave discharge

- SWS

Slow-wave sleep

- TC

Thalamocortical

- VGCC

Voltage-gated calcium channel

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bers D.M. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415(6868):198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bers D.M. Calcium and cardiac rhythms: physiological and pathophysiological. Circ. Res. 2002;90(1):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berggren P.O., Yang S.N., Murakami M., Efanov A.M., Uhles S., Kohler M., et al. Removal of Ca2+ channel beta3 subunit enhances Ca2+ oscillation frequency and insulin exocytosis. Cell. 2004;119(2):273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catterall W.A., Perez-Reyes E., Snutch T.P., Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005;57(4):411–425. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catterall W.A. Interactions of presynaptic Ca2+ channels and snare proteins in neurotransmitter release. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;868:144–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catterall W.A. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bito H., Deisseroth K., Tsien R.W. Ca2+-dependent regulation in neuronal gene expression. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1997;7(3):419–429. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(97)80072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmann F., Lacinova L., Klugbauer N. Voltage-dependent calcium channels: from structure to function. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;139:33–87. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ertel E.A., Campbell K.P., Harpold M.M., Hofmann F., Mori Y., Perez-Reyes E., A. Schwartz. Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron. 2000;25(3):533–535. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83(1):117–161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirksen R.T., Beam K.G. Single calcium channel behavior in native skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 1995;105(2):227–247. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koschak A., Reimer D., Huber I., Grabner M., Glossmann H., Engel J., Striessnig J. alpha 1D (Cav1.3) subunits can form l-type Ca2+ channels activating at negative voltages. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(25):22100–22106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platzer J., Engel J., Schrott-Fischer A., Stephan K., Bova S., Chen H., Zheng H. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michna M., Knirsch M., Hoda J.C., Muenkner S., Langer P., Platzer J., Striessnig J. Cav1.3 (alpha1D) Ca2+ currents in neonatal outer hair cells of mice. J. Physiol. 2003;553(Pt 3):747–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu W., Lipscombe D. Neuronal Ca(V)1.3alpha(1) L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J. Neurosci. 2001;21(16):5944–5951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hockerman G.H., Peterson B.Z., Johnson B.D., Catterall W.A. Molecular determinants of drug binding and action on L-type calcium channels. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:361–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Striessnig J., Grabner M., Mitterdorfer J., Hering S., Sinnegger M.J., Glossmann H. Structural basis of drug binding to L Ca2+ channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19(3):108–115. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Striessnig J. Pharmacology, structure and function of cardiac L-type Ca(2+) channels. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 1999;9(4-5):242–269. doi: 10.1159/000016320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klint J.K., Berecki G., Durek T., Mobli M., Knapp O., King G.F., Adams D.J. Isolation, synthesis and characterization of omega-TRTX-Cc1a, a novel tarantula venom peptide that selectively targets L-type Cav channels. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;89(2):276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arranz-Tagarro J.A., de los Rios C., Garcia A.G., Padin J.F. Recent patents on calcium channel blockers: emphasis on CNS diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2014;24(9):959–977. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.940892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricoy U.M., Frerking M.E. Distinct roles for Cav2.1-2.3 in activity-dependent synaptic dynamics. J. Neurophysiol. 2014;111(12):2404–2413. doi: 10.1152/jn.00335.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassola A.C., Jaffe H., Fales H.M., Afeche S.C., Magnoli F., Cipolla-Neto J. omega-Phonetoxin-IIA: a calcium channel blocker from the spider Phoneutria nigriventer. Pflugers Arch. 1998;436(4):545–552. doi: 10.1007/s004240050670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutton K.G., Siok C., Stea A., Zamponi G.W., Heck S.D., Volkmann R.A., Ahlijanian M.K. Inhibition of neuronal calcium channels by a novel peptide spider toxin, DW13.3. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;54(2):407–418. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prashanth J.R., Brust A., Jin A.H., Alewood P.F., Dutertre S., Lewis R.J. Cone snail venomics: from novel biology to novel therapeutics. Future Med. Chem. 2014;6(15):1659–1675. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng K., Chen X.D., Liang S.P. The effect of Huwentoxin-I on Ca(2+) channels in differentiated NG108-15 cells, a patch-clamp study. Toxicon. 2001;39(4):491–498. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(00)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillyard D.R., Monje V.D., Mintz I.M., Bean B.P., Nadasdi L., Ramachandran J., Miljanich G. A new Conus peptide ligand for mammalian presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 1992;9(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mintz I.M., Venema V.J., Swiderek K.M., Lee T.D., Bean B.P., Adams M.E. P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin omega-Aga-IVA. Nature. 1992;355(6363):827–829. doi: 10.1038/355827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boland L.M., Morrill J.A., Bean B.P. omega-Conotoxin block of N-type calcium channels in frog and rat sympathetic neurons. J. Neurosci. 1994;14(8):5011–5027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-05011.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis R.J., Nielsen K.J., Craik D.J., Loughnan M.L., Adams D.A., Sharpe I.A., Luchian T. Novel omega-conotoxins from Conus catus discriminate among neuronal calcium channel subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(45):35335–35344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis R.J. Ion channel toxins and therapeutics: from cone snail venoms to ciguatera. Ther. Drug Monit. 2000;22(1):61–64. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200002000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meunier F.A., Feng Z.P., Molgo J., Zamponi G.W., Schiavo G. Glycerotoxin from Glycera convoluta stimulates neurosecretion by up-regulating N-type Ca2+ channel activity. EMBO J. 2002;21(24):6733–6743. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz R.A., Sancho J., Serratosa J. Antiepileptic drug interactions. Neurologist. 2008;14(6) Suppl. 1:S55–S65. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000340792.61037.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berecki G., McArthur J.R., Cuny H., Clark R.J., Adams D.J. Differential Cav2.1 and Cav2.3 channel inhibition by baclofen and alpha-conotoxin Vc1.1 via GABAB receptor activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014;143(4):465–479. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuang R.S., Jaffe H., Cribbs L., Perez-Reyes E., Swartz K.J. Inhibition of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels by a new scorpion toxin. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1(8):668–674. doi: 10.1038/3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith E.M., Sorota S., Kim H.M., McKittrick B.A., Nechuta T.L., Bennett C., Knutson C. T-type calcium channel blockers: spiro-piperidine azetidines and azetidinones-optimization, design and synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20(15):4602–4606. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Francois A., Laffray S., Pizzoccaro A., Eschalier A., Bourinet E. T-type calcium channels in chronic pain: mouse models and specific blockers. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466(4):707–717. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hildebrand M.E., Smith P.L., Bladen C., Eduljee C., Xie J.Y., Chen L., Fee-Maki M. A novel slow-inactivation-specific ion channel modulator attenuates neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152(4):833–843. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun H.S., Hui K., Lee D.W., Feng Z.P. Zn2+ sensitivity of high and low-voltage activated calcium channels. Biophys. J. 2007;93(4):1175–1183. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.103333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park S.J., Min S.H., Kang H.W., Lee J.H. Differential zinc permeation and blockade of L-type Ca channel isoforms Ca1.2 and Ca1.3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]