Abstract

Background & objectives:

Yttrium-90 (90Y)-based radioembolization has been employed to treat hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as commercial radioactive glass and polymeric resin microspheres. However, in India and other Asian countries, these preparations must be imported and are expensive, validating the need for development of indigenous alternatives. This work was aimed to develop an economically and logistically favourable indigenous alternative to imported radioembolizing agents for HCC therapy.

Methods:

The preparation of 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres was optimized and in vitro stability was assessed. Hepatic tumour model was generated in Sprague-Dawley rats by orthotopic implantation of N1S1 rat HCC cell line. In vivo localization and retention of the 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres was assessed for seven days, and impact on N1S1 tumour growth was studied by histological examination and biochemical assays.

Results:

Under optimal conditions, >95% 90Y-labelling yield of Biorex70 resin microspheres was obtained, and these showed excellent in vitro stability of labelling (>95%) at seven days. In animal studies, 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres were retained (87.72±1.56% retained in liver at 7 days). Rats administered with 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres exhibited lower tumour to liver weight ratio, reduced serum alpha-foetoprotein level and greater damage to tumour tissue as compared to controls.

Interpretation & conclusions:

90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres showed stable retention in the liver and therapeutic effect on tumour tissue, indicating the potential for further study towards clinical use.

Keywords: Biorex 70 resin, hepatocellular carcinoma, radioembolization, therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals, yttrium-90

In several Asian and African countries hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the major cause of death from cancer1,2. More than 80 per cent of HCC patients have inoperable disease with poor prognosis3 : Two-thirds of patients survive less than two years, with less than five per cent achieving a five year survival rate3,4,5,6.

The need for strict selection criteria to avoid post-operative liver failure (in case of concomitant liver cirrhosis) restricts the possibility of resective surgery to only 10-37 per cent of HCC cases7,8,9. The established anti-cancer drugs including sorafenib, tamoxifen and octreotide have proved ineffective in systemic HCC chemotherapy, with less than 20 per cent response rate and no significant survival benefit7,10,11. External beam radiotherapy has limited applicability for HCC, primarily due to the possibility of radiation induced liver disease (RILD)12. While percutaneous intervention (PI) with ethanol can achieve 90-100 per cent response rates in tumours <2 cm diameter, this drops to 50 per cent for tumours with ≥5 cm diameter7,13.

Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) has been practised for more than three decades14,15, employing drugs like cisplatin, doxorubicin, methotrexate, paclitaxel, etc. in conjunction with lipiodol or other embolizing agents for regional therapy16,17. Embolization in conjunction with a therapeutic radiopharmaceutical, viz. radioembolization, is more tumour specific vis-à-vis systemic radiotherapy, restricting damage to normal liver and diminishing RILD complications18.

The two principal approaches to radioembolization for HCC are: (i) Using lipiodol as a carrier of radioactivity. Iodine-131 (131I) labelled lipiodol has been tested in clinical trials as a therapeutic radiopharmaceutical for HCC19, but the preparation is cumbersome, the 8.04 day half-life and 364keV gamma emissions may cause unnecessary non-specific dose absorption, and stability of the exchange label may be an issue for extended in vivo use. Rhenium-188 (188Re) labelled lipiodol, prepared in the clinic using 188Re obtained from a Tungsten-188 (188W)-Rhenium-188 (188Re) generator has also been reported in clinical trials with promising results20; (ii) Using a micron-range diameter particulate carrier that can adsorb or encapsulate a therapeutic radionuclide like Yttrium-90 (90Y), it would be feasible to localize the 90Y activity selectively to the tumour vasculature. Here, particle diameter of the carrier is primarily responsible for localization of the radioactivity in the administered region. The high tissue penetration range (12 mm max) of pure beta-emissions [Eβmax = 2.28 MeV] of 90Y allows uniform dose distribution even with a heterogeneously localized radiopharmaceutical. Its 64.1 h half life is convenient for preparation and delivery of the radiopharmaceutical to the patient, yet sufficiently short to achieve critical dose rate with lower long-term adverse consequences21. 90Y-labelled microparticles like Theraspheres® (90Y-encapsulating glass microspheres from Nordion Inc., Canada) and SIR-spheres® (90Y-tagged polymeric microspheres from Sirtex Medical Ltd. Australia) have been tested for their potential in treatment of HCC or liver metastasis, where these have shown good promise and have been FDA approved for clinical use22. In the Indian context, these preparations must be imported, and are in consequence beyond the economic reach of majority of the patients requiring treatment for HCC.

The majority of 90Y-production is by generator-based separation from 90Sr. While traditionally, column-based solvent extraction techniques have been used to provide 90Y for clinical use, a novel electrochemical generator is now used to separate high specific activity 90Y from 90Sr for this purpose23. Towards the development of 90Y based preparations for HCC, Yu et al24 have reported the preparation of 90Y-labelled oxine in lipiodol and its preliminary in vivo distribution study in rabbits by gamma imaging. Their results provide sufficient promise for a more in-depth evaluation. Biorex 70 has an acrylic matrix with appended carboxylic acid groups. While the 90Y-labelling of microspheric Biorex 70 resin has been reported25,26, no literature pertaining to detailed biological studies performed with such microspheres has been encountered.

The work reported here focuses on the development and biological evaluation in animal model of a 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microsphere based embolization complex that may serve as a therapeutic vehicle for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Material & Methods

Biorex70 micro particulate cation exchange resin (200-400 dry mesh size, 45-75 μm wet bead size) was procured from Bio-rad, USA. Oxine (8-hydroxyquinoline), ammonium acetate, sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate were obtained from Sigma, USA. Lipiodol was obtained from Guerbet, France. Ethanol and chloroform were procured from Merck, India. Double distilled water was used to prepare all solutions.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats employed in the animal studies were procured from the Animal House of the Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer - Tata Memorial Centre (ACTREC-TMC), Navi Mumbai, India. Animal studies were performed after due approval from the institutional animal ethics committee. N1S1 rat liver carcinoma cell line of Sprague-Dawley origin (ATCC CRL-1604) was procured by and cultured at ACTREC towards use in development of orthotopic animal tumour model for this study. Ethicon surgical sutures (Johnson & Johnson, India) were used during surgical procedures. BD Vacutainer® tubes (Beckton-Dickinson, India) suitable for whole blood and serum were used to collect blood for various investigations. For haemoglobin estimation, Drabkin's reagent was obtained from Sigma, USA. Kits for estimating serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were obtained from Bioquant, USA. Serum bilirubin was estimated using kit obtained from Bioscientific Corporation, USA. Serum alpha-foetoprotein levels were estimated using ELISA kit from MP Biomedicals, USA.

Orbital shaker-incubator from Biosystem Scientific, India, was used for radiolabelling reactions. Radioactivity measurements for 90Y-labelling studies were carried out using a well type NaI (Tl) scintillation detector (ECIL, India). Radioactivity measurements for in vivo distribution studies were performed on an integral line flat-bed NaI (Tl) scintillation detector (Harshaw, USA). In both cases, Bremsstrahlung radiation resulting from the β-emissions of 90Y was measured.

Separation of 90Y from 90Sr: 90Y of high radionuclidic purity (<0.0005% 90Sr) was obtained by a two-step electrolytic process from a 90Sr/90Y equilibrium mixture in 2 M HNO3 using an in-house developed electrochemical 90Sr/90Y generator described elsewhere23. In the first step, electrolysis was performed for 90 min in 90Sr(NO3)2 feed solution at pH 2-3 at a potential of -2.5V with 100-200 mA current using platinum electrodes. In the second electrolysis step, the platinum cathode on which 90Y was deposited during the first cycle of electrolysis was used as anode and a fresh circular platinum electrode was used as cathode. The second electrolysis step was performed for 45 min in 3 mM HNO3 at a potential of -2.5V with 100 mA current. 90Y deposited on the cathode after the second electrolysis was dissolved in 0.1N HCl to obtain 90YCl3.

Preparation of 90Y -labelled Biorex 70 microspheres: Biorex 70 microspheres (5 mg) were suspended in one ml of freshly prepared 0.1 M ammonium acetate solution (pH 5.5-6.0). To this, up to 185 MBq of 90YCl3 was added. The pH was adjusted if necessary to ~5.0 using 0.1 N HCl. The above reaction mixture was kept on an orbital shaker incubator for different time periods at room temperature. At the end of the labelling reaction, the microspheres were separated by centrifugation at 1200×g for 10 min and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The percentage of 90Y-activity associated with the microspheres in comparison to 90Y-radioactivity in the reaction mixture was taken as the radiolabelling yield. Stability of the labelled product was tested by suspending it in PBS at 37°C, and measuring the activity leaching out into the supernatant at different time periods using the above technique. For the final application, 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres were suspended in 2 ml PBS.

In vivo studies: Sprague-Dawley rats (Male, 6-8 wk, 150-200 g) were taken for in vivo assessment of 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres. The rats were maintained on normal diet - food and water provided ad libitum. For tumour model development, they were orthotopically transplanted with N1S1 rat HCC cell line (4 animals per time-point, 3 × 106 cells per animal) by sub-capsular injection on left liver lobe. The procedure was performed under isoflurane anaesthesia. Optimized protocol gave appreciable size single lesions in about three weeks.

To study the in vivo retention pattern of 90Y-Biorex microspheres, the radioactive preparation was administered into the N1S1 tumour bearing rats by injection using 30G 1/2” needle as per previously reported protocol27. Prior to administration, the animals were fasted for six hours, and the procedure was performed under anaesthesia with a mixture of xylazine:ketamine (1:10). The 90Y-labelled microspheres (50 μl) were slowly injected (20-25 sec) into the hepatic vessel via a 30G 1/2” needle. The site of injection was gently pressed with a gauze pad to stem any bleeding and then the incision was closed up with surgical suture. At the end of the procedure, the animals recovered from anaesthesia. Post recovery, food and water were provided ad libitum and they were kept under normal conditions till the time of sacrifice/biodistribution and closely monitored during this period for any signs of disability or distress. At the end of the respective incubation periods, the animals were sacrificed by exposure to carbon dioxide saturated atmosphere. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture. The animals were then dissected and the relevant organs and tissues were excised for measurement of associated radioactivity to assess leaching of the radiolabelled preparation from the region of interest and its subsequent spread to non-specific regions. Using an identical protocol with the same number of animals (4 animals per time-point, 3 × 106 tumour cells per animal) as for Biorex 70 microspheres, a direct comparison of in vivo distribution pattern was drawn with 90Y-labelled oxine in lipiodol, previously reported as a potential HCC therapy agent24.

Biological efficacy was assessed with a combination of biochemical and histological assays. For this, a separate set of tumour-bearing animals (4 animals per time-point, 3 × 106 cells per animal) administered with unlabelled “cold” preparation was used as a control for comparison. Serum was separated for relevant biochemical assays, including ALT and AST activity for liver function assessment, and alpha-foetoprotein (AFP) concentration as a marker of HCC. Liver tumour tissue samples were taken for histological analysis to assess biological efficacy of the therapeutic preparations by the following protocol: Samples of liver tissue were suspended in 10 per cent neutral buffered formalin for 24-48 h for preservation of the tissue structure. These were washed several times with water to remove all traces of formalin. Finally, these were suspended in 70 per cent ethanol solution for preservation and stored at 4°C, allowing adequate time for decay of 90Y radioactivity (10 times half-life), before preparation of histological blocks and slides.

All quantitative results were reported as mean±SD, unless otherwise indicated. Applying Student's t-test, P values for the relevant biochemical parameters of the different treatment groups were calculated taking corresponding mean value of 4-week N1S1 tumour control as a hypothetical mean.

Results

The in-house electrochemical 90Sr/90Y generator was effective in providing ~3.7GBq of no-carrier-added (NCA) 90Y per batch23, which could be separated in ≥90 per cent yield. The level of 90Sr in the separated 90Y was well within the permissible limits (<0.0005%), as estimated by extraction paper chromatography23.

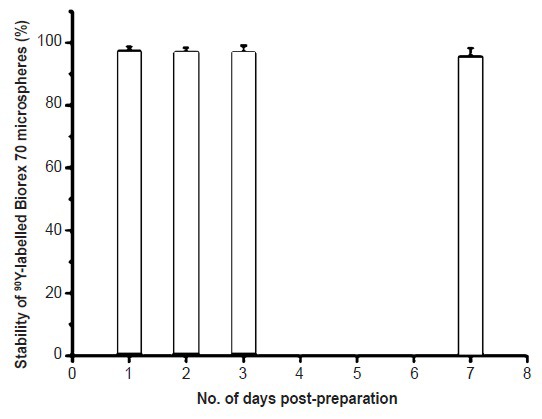

Preparation of 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres: There was no variation in radiolabelling yield with reaction time. It was evident that the binding of 90Y to the cationic Biorex 70 resin microspheres was extremely rapid; as early as 15 min, the labelling yield was ~95 per cent, which was retained up to 55 min. Stability in PBS was also excellent, with >95 per cent of the 90Y-activity associated with the microspheres for as long as seven days post-preparation at 37°C (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Post-preparation stability of 90Y-Biorex 70 microspheres in PBS at 37°C (values shown as mean ± SD, n=3).

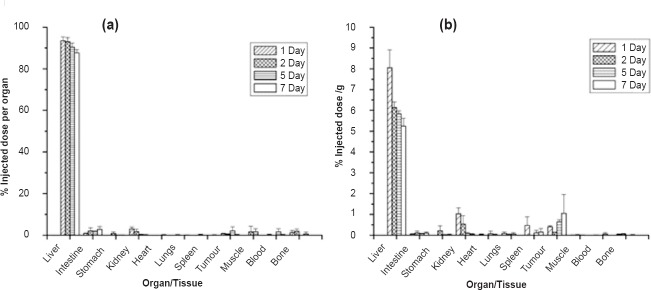

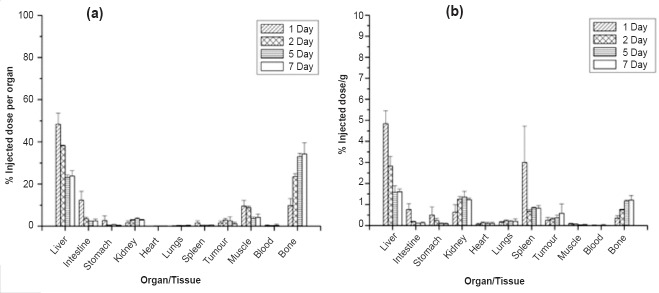

In vivo distribution studies: Fig. 2a and b shows the in vivo distribution of 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres in the tested tumour model in terms of per organ and per gram, respectively. The Biorex 70 preparation was effectively localized in the liver tissue, with minimal leaching of 90Y activity to other organs. Even at seven days post-administration, 87.72±1.56 per cent of the injected dose (ID) was associated with the liver. The association of 90Y activity with non-target regions was also minimal. Throughout the period of study, accumulation of 90Y activity in the bone remained low, with 0.56±0.97 per cent ID (0.01±0.02% ID/g) bone activity measured at seven days. In contrast, in vivo distribution of 90Y-oxine in lipiodol showed limited stability, with significant (~60%) leaching of 90Y-activity from the liver as early as 48 h p.i. (post-injection) and more than 30 per cent accumulation in the bone at seven days p.i. (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

In vivo distribution profile of 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres in N1S1 orthotopic tumour bearing Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, data given in terms of % injected dose (a) per organ (b) per gram (n=4).

Fig. 3.

In vivo distribution profile of 90Y-labelled oxine in lipiodol in N1S1 orthotopic tumour bearing Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, data given in terms of % injected dose (a) per organ (b) per gram (n=4).

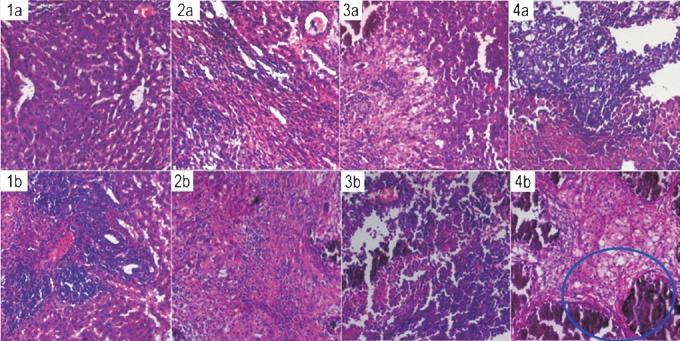

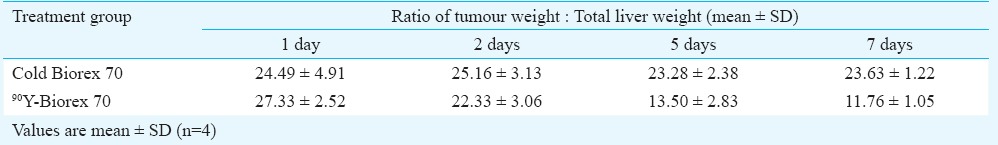

Biological efficacy studies: To assess biological efficacy of the 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres comparison studies were performed with unlabelled (cold) Biorex 70 microspheres. The Table gives the per cent weight of tumour to total liver weight for the different treatment groups, which provides insight into the effect of exposure to cold and 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres on tumour size. The mean ratio of tumour weight to total liver weight in the animals injected with the cold preparation was 23.63±1.22 per cent at seven days, while it dropped significantly to 11.76±1.05 per cent in the experimental set administered with the 90Y-labelled Biorex microspheres. Fig. 4 depicts the results of histologic examination for tumour models with 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres in comparison with the unlabeled (cold) microspheres. Cold Biorex 70 microparticles were seen to exhibit some embolic effect in terms of tissue damage immediately surrounding the vasculature. However, in the group administered with 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres, extensive cellular damage and necrotic morphology was observed across the tumour tissue, especially at five and seven days p.i. suggesting a therapeutic effect of the β-emissions of 90Y.

Table.

Comparison of treatment groups in terms of percentage ratio of N1S1 tumour weight to total liver weight

Fig. 4.

Histological sections of N1S1 tumour tissue from animals administered with (1a-4a) cold Biorex 70 microspheres for 1, 2, 5 and 7 days, respectively and (1b-4b) 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres for the same time intervals (Magnification 10x). Area circled in blue shows regions of greater necrotic damage in the tumour tissue.

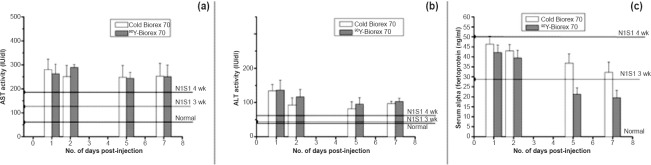

Biochemical assays were performed on the serum of tested animals (from blood collected at the time of sacrifice) to assess impact of the treatment on relevant serum parameters. Serum levels of liver function enzymes were comparable to those in case of treatment with cold Biorex 70 microspheres over the period of experiment [AST 262±40.31 IU/dl and ALT 136±29.4 IU/dl] at day 1, AST 250±48.0 IU/dl and ALT 103.25±9.5 IU/dl at seven days p.i. (Fig. 5a, b). These levels were slightly increased over the values for N1S1 tumour controls (4 wk), referred above. Serum alpha-foetoprotein levels show good correlation with tumour reduction (Fig. 5c). In the case of animals administered with 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres, the mean serum AFP level at seven days p.i. (19.49±3.72 mg/ml), was significantly lower than for cold Biorex 70 microspheres (32.29±5.12 ng/ml, P<0.01) and less than half of the value for the N1S1 control animals at four weeks (51.44±11.97 ng/ml) corresponding with the reduced tumour size in those animals.

Fig. 5.

Impact of 90Y-based radioembolic treatment on (a) aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (b) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (c) serum alpha-foeto protein (AFP) levels of N1S1-tumour bearing Sprague-Dawley rats. Values are mean ± SD (n=4).

Discussion

In this study, commercially available Biorex 70 microspheres were labelled with 90Y-activity obtained from an in-house generator. Apart from the efficacy, availability of the radionuclide is an important factor to be considered for regular sustainable use of a radiopharmaceutical. Though 188Re based molecules have been studied in the past and shown to be effective20, but 188Re is not widely available and the limited options are expensive, therefore, 90Y offers an attractive alternate. 90Y was available from an indigenous generator making it more economical compared to 188Re for clinical work. For the biological efficacy studies, 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres were compared with in-house 90Y-labelled oxine in lipiodol prepared using a previously reported protocol24. In a previously reported study28, Biorex 70 microspheres labelled with PET isotope yttrium-86 (86Y) were tested for their in vivo stability in terms of pulmonary retention after tail vein catheterization; the results of imaging studies showed stable retention in the lung for up to 24 h post-administration. In the current study, 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres showed stable retention in the liver at seven days p.i. (corresponding to approximately 2.5 half-lives of 90Y), indicating excellent stability and retention of the radiolabelled preparation. In comparison, 90Y-labelled oxine showed more than 30 per cent bone accumulation at seven days post-administration, similar to that reported by us earlier for 177Lu-labelled oxine in lipiodol27. It is proposed that 90Y does not remain stably attached to oxine in vivo and leaches out as free 90Y, which then accumulates in the bone. Yu et al24 had studied in vivo distribution for only up to 48 h, and their observations were by way of Bremsstrahlung imaging using absence of 90Y-activity in the lungs as an index of stable hepatic retention. This pharmacokinetic profile in our study suggests that 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres would be safer in terms of non-specific dose and therapeutically more effective due to significantly longer stable localization in the region of interest. The mean ratio of tumour to liver weight in the case of animals administered with 90Y-labelled Biorex 70 microspheres was almost 50 per cent that of those treated with cold Biorex 70, indicating a significant gross impact of 90Y radiation on the tumour lesion. The fall in serum AFP in these animals complemented the above observation. Although the AFP levels were still significantly above normal, perhaps on account of residual tumour tissue, this demonstrates that sustained presence of 90Y activity from the microspheres gives a measurable therapeutic effect in the tested model for hepatocellular carcinoma.

In conclusion, the high 90Y-labelling yield, high stability of labelled product, stable retention in the region of interest in the tested animal model, and demonstrable therapeutic effect as seen from measurement of relevant parameters in the period of study, indicate that Biorex 70 microspheres hold good potential to be taken up for further studies towards possible use in the clinic.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Dr Arvind Ingle, In-Charge, Animal House, ACTREC-TMC for arranging the supply of animals required and for providing the facility for histology. Authors acknowledge the significant technical contribution of Dr Kiran Bendale, ACTREC-TMC, in the animal model development studies, and Dr Rubel Chakravarty, Isotope Applications and Radiopharmaceuticals Division, BARC, for help in procuring 90Y.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Blum HE. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Therapy and prevention. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7391–400. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundram FX. Radionuclide therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2006;2:e40. doi: 10.2349/biij.2.3.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huynh H. Molecularly targeted therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:550–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalva SP, Thabet A, Wicky S. Recent advances in trans-arterial therapy of primary and secondary liver malignancies. Radiographics. 2008;28:101–17. doi: 10.1148/rg.281075115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Boix L, Sala M, Llovet JM. Focus on hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:215–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbara L, Benzi G, Gaiani S, Fusconi F, Zironi G, Siringo S, et al. Natural history of small untreated hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of tumor growth rate and patient survival. Hepatology. 1992;16:132–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poon RT, Fan ST, Tsang FH, Wong J. Locoregional therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: A critical review from the surgeon's perspective. Ann Surg. 2002;235:466–86. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, et al. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421–30. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman M, Klein A. AASLD single-topic research conference on hepatocellular carcinoma: Conference proceedings. Hepatology. 2004;40:1465–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.20528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuen MF, Poon RT, Lai CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Wong KW, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled study of long-acting octreotide for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;36:687–91. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow PK, Tai BC, Tan CK, Machin D, Win KM, Johnson PJ, et al. High-dose tamoxifen in the treatment of inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2002;36:1221–6. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibrahim SM, Lewandowski RJ, Sato KT, Gates VL, Kulik L, Mulcahy MF, et al. Radioembolization for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A clinical review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1664–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lencioni RA, Allgaier HP, Cioni D, Olschewski M, Deibert P, Crocetti L, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: randomized comparison of radio-frequency thermal ablation versus percutaneous ethanol injection. Radiology. 2003;228:235–40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281020718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemo-embolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, Senzolo M, Cholongitas E, Davies N, et al. Tran-sarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Inter Rad. 2007;30:6–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis AL, Dreher MR. Locoregional drug delivery using image-guided intra-arterial drug eluting bead therapy. J Control Release. 2012;161:338–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewandowski RJ, Geschwind JF, Liapi E, Salem R. Transcatheter intraarterial therapies: rationale and overview. Radiology. 2011;259:641–57. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salem R, Hunter RD. Yttrium-90 microspheres of the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:S83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung DK, Divgi C. Trans-arterial I-131 lipiodol therapy of liver tumors. In: Aktolun C, Goldsmith SJ, editors. Nuclear medicine therapy. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2013. pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A, Srivastava DN, Chau TT, Long HD, Bal C, Chandra P. Inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial 188 Re HDD-labeled iodized oil for treatment-prospective multicenter clinical trial. Radiology. 2007;243:509–19. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2432051246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S. Bifunctional coupling agents for radiolabeling of biomolecules and target-specific delivery of metallic radionuclides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1347–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riaz A, Salem R. Yttrium-90 radioembolization in the management of liver tumors: expanding the global experience. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:451–2. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakravarty R, Pandey U, Manolkar RB, Dash A, Venkatesh M, Pillai MRA. Development of an electrochemical separation of 90Y suitable for targeted therapy. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:245–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Hafeli UO, Sands M, Dong Y. 90Y-oxine-ethiodol, a potential radiopharmaceutical for the treatment of liver cancer. Appl Radiat Isot. 2003;58:567–73. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hafeli UO. Radioactive Microspheres for Medical Applications. In: De Cuyper M, Bulte JWM, editors. Physics and chemistry basis of biotechnology. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. pp. 213–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann A, Schubiger PA, Mettler D, Geiger L, Triller J, Rösler H. Renal pathology after arterial Y-90 microsphere administration in pigs: A model for superselective radioembolization therapy. Invest Radiol. 1995;30:716–23. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian S, Das T, Chakraborty S, Sarma HD, Banerjee S, Samuel G, et al. Preparation of 177 Lu-labeled oxine in lipiodol as a possible agent for therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: A preliminary animal study. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2010;25:539–43. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avila-Rodriguez MA, Selwyn RG, Hampel JA, Thomadsen BR, DeJesus OT, Converse AK, et al. Positron-emitting resin microspheres as surrogates of 90Y SIR-Spheres: a radiolabeling and stability study. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:585–90. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]