Abstract

There is increasing interest, in the UK and elsewhere, in involving the public in health care priority setting. At the same time, however, there is evidence of lack of clarity about the objectives of some priority setting projects and also about the role of public involvement. Further, some projects display an apparent ignorance of both long‐standing theoretical literature and practical experience of methodologies for eliciting values in health care and related fields. After a brief examination of the context of health care priority setting and public involvement, this paper describes a range of different approaches to eliciting values. These approaches are critically examined on a number of dimensions including the type of choice allowed to respondents and the implications of aggregation of values across individuals. Factors which affect the appropriateness of the different techniques to specific applications are discussed. A check‐list of questions to be asked when selecting techniques is presented.

Keywords: priorities, priority setting, public involvement, values

Introduction

There is increasing interest, in the UK and elsewhere, in involving the public in health care priority setting. At the same time, however, there is evidence of a lack of clarity about the objectives of some priority‐setting projects and also about the role of public involvement. Further, some projects display an apparent ignorance of both long‐standing theoretical literature and practical experience of methodologies in health care and related fields. The objective of this paper is to describe and examine critically a range of different approaches to eliciting values. Factors which affect the appropriateness of the different techniques to specific applications are discussed and a check‐list of questions to be asked when selecting techniques is presented. However, since the appro‐ priateness of a technique depends on the context in which it is used, there will first be a brief discussion concerning public involvement in priority setting and methods of engaging the public.

Involving the public in priority setting

Public involvement

Although many commentators appear to consider its desirability as axiomatic, the notion of public involvement in health care is not unproblematic. This is especially the case with collective participation, as ‘citizens’ and as (potential) users, in decisions that affect the range of services made available, and to whom. For instance, Grimley Evans argues that an approach that puts the rights of individual citizens in the hands of other citizens is fallacious as:

…one of the principles of the British state is that all citizens are equal in having equal status before the law and equal basic access to the means of life, education and health. 1

The extent and nature of public involvement in health care vary considerably. 2 Arnstein demonstrated this in her useful ‘ladder of participation’, which descends from citizen control, though consultation and informing, to manipulation. 3 Mullen et al. made a distinction between ‘reactive’ and ‘proactive’ or ‘initiator’ involvement. 4 Such distinctions affect not only approaches to involvement but also how the function, validity and very nature of public involvement are viewed by health care providers and by society.

Priority setting

Health care priorities are set and choices are made in many different contexts. At government level priorities are set between the health service and competing claims for funds; health service resources are allocated between geographical areas and specialties; choices are made between centralizing and dispersing facilities; priorities affect the order and the way in which services are delivered (e.g. what priority to give to the right to choose a female doctor) and decisions are made between individual patients. There are thus a number of opportunities and areas for public involvement in different capacities, some of which are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Areas and opportunities for public involvement

Many of the most controversial and interesting debates centre around the second and third areas. However, in practice, public involvement frequently focuses on the fourth and fifth. These relate to how services are provided and are of considerable importance to both providers and users of health services. They offer considerable scope for public involvement and few problems of legitimacy but have been overshadowed in recent debates in the UK by questions of which services should be provided and to whom – explicit rationing. 5 , 6

Approaches to ‘engaging’ the public

The objectives of the exercise – the use to which the results will be put and the type of priority setting being addressed – will determine who should be involved (the target population), and how. The target population may consist of the general population at large, users of a specific service or sufferers from a particular condition. The choice of methodology to ‘engage’ the public will be influenced also by whether the aim is to obtain results generalizable to the whole target population or to ‘set the agenda’, for example determining which issues are of concern to respondents.

A wide range of methods are used to involve the public. Some ‘mass’ approaches, such as telephone hot‐lines, public meetings, advertisements in newspapers and leaflets, sometimes including reply forms or simple questionnaires, largely leave the initiative to the public to become involved. Other ‘mass’ approaches include using either self‐completion questionnaires or interviews in surveys with random samples large enough to permit generalizations to be made about the population from which the sample is drawn.

Of increasing popularity, especially in identifying issues of concern to users or the public, are small‐scale discussion or focus groups. Some such groups are constructed to be ‘representative’ of their target population, in the sense that their membership reflects the composition of the target population, whilst the make‐up of others is more opportunistic. Along with other qualitative approaches such as small‐scale surveys with in‐depth interviews, such groups permit issues to be explored in‐depth and, to a certain extent, allow participants to set the agenda. However, whilst focus groups can help to identify the range of views held, even ‘representative’ groups cannot be used to make statistical generalizations about the target population.

Some approaches use proxies. For example, Rapid Appraisal, pioneered in developing countries, is increasingly popular. This approach seeks to determine community views by interviewing key people (e.g. teachers, home helps, corner‐shop owners, etc.), deemed to be in touch with local opinion. Attempts have been made to determine patients’ views by surveying general practitioners (GPs), despite evidence that GPs’ views can differ considerably from those of their patients. 7

Some methods attempt to ensure ‘informed’ involvement by providing participants with information. Citizens’ Juries involve a ‘representative’ panel of ‘citizens’, which meets over several days, hears evidence on a particular issue and ‘delivers its verdict’. 8 , 9, –10 ‘Standing’ groups of consumers, who are involved over a period of time, have been assembled. These range from focus groups with continuing membership, which meet periodically 11 to standing panels of over 1000 local residents, who complete a series of questionnaires on different issues. However, informing the public prior to their involvement, and repeated involvement of the same members of the public, may not always be appropriate. There may well be instances where the objective is to secure involvement by the public ‘at large’, ‘uncontaminated’ by professional views or information.

Methods of eliciting values

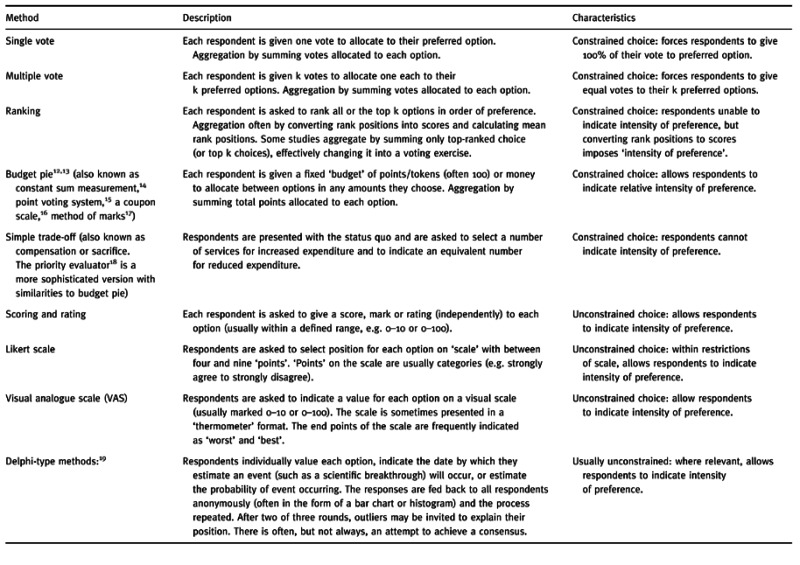

Having ‘engaged’ the public, there are many different methods which can be used to elicit their values and preferences, some of which are listed in Table 2, 3 2. Choice of the most appropriate method for any particular application is important since different methods of eliciting values and different methods of aggregating values across individuals can yield totally different results.

Table 2.

Some methods of eliciting preferences

Table 3.

Table 2 (contd.)

In addition to the choice of method being important, the wording of questions and the way that they are presented can influence responses. With scaling/rating in value elicitation there can be order effects. For example, Knox, reporting a large national survey scoring the importance of life domains each on an 11‐point ladder‐scale, found the results skewed towards the top end of the scale. 31 Hoinville & Courtenay describe a method of presenting a scale with ‘opposite’ statements at each end, with respondents being asked to indicate their own position on the scale. 32 Order effects were tested for by switching the ends at which the statements were placed for half the respondents. The results revealed a marked order effect with respondents tending to endorse the right‐hand box.

With budget pie, it is important to allow enough points or tokens (circa 100) to permit respondents sufficient discrimination in allocating them between options. One unpublished study, with a budget of only 15 tokens, reported respondents wishing to cut tokens in half. Other presentation effects have been observed. Hoinville & Courtenay describe an exercise in which the number of points available was successively reduced. 33 Respondents, however, did not reduce their allocation to each option or aspect proportionately. Some aspects retained all or most of their allocation, thus increasing their share of the ‘pie’. It is not clear, however, whether this effect was the result of asking respondents to repeat their allocations with successively fewer points (i.e. effectively moving from their initial allocation) or the result of the absolute number of points permitted at each stage.

Using methods in practice

Among the less complex methods, ranking and scaling/rating were found to be widely employed in projects identified in the literature and in a UK survey of priority setting in the health service, reported fully elsewhere. 34 Voting was also used in a number of projects (see Box 4 1). A few applications of budget pie and its two‐option variant, constant‐sum paired comparison, were found (see Box 5 2). Box 6 3 outlines some applications of ‘constrained rating’. Several projects used a range of different methodologies at various stages (Box 7 4).

Table 4.

Box 1 Use of single and multiple voting

Table 5.

Box 2 Use of budget pie, simple trade‐off and constant‐sum paired comparison

Table 6.

Box 3 Applications of ‘constrained rating’

Table 7.

Box 4 Use of multiple approaches

Amongst the more complex techniques, few health care applications were found. For example, although the analytical hierarchy process (AHP) is widely used within industry and private sector organizations, and also elsewhere within the public sector, there appear to be few health service applications. However, Dolan and colleagues do report its use in assisting individual patients to choose between treatments. 43 , 44 Dolan concluded that:

…AHP‐based decision‐making aids are likely to be acceptable to and within the capabilities of many patients 45

Despite early applications of measure of value, in the USA in health agency decision making 46 and in the UK to attach values (or priority weights) to plan proposals before forwarding them to the area health authority, 47 no recent health care applications were detected.

Which method is the most appropriate?

Many of the techniques listed in Table 2, 3 2 have a long history in a range of disciplines, including economics, operational research, psychology, political science and philosophy, and many are grounded within those disciplinary theories. However, theoretical validity does not always coincide with acceptability, people’s comprehension and even people’s value systems. It is thus important to get the correct balance between theoretical validity and user acceptability. At the very least, investigators should understand the values implicit in their chosen technique, the form of choice being imposed on respondents, the implications of aggregation, and, most importantly, its appropriateness for the purpose of the exercise.

Single versus multi‐attribute approaches

Most health care decisions involve a number of, often competing, criteria or attributes. Some approaches, for example AHP, explicitly incorporate two or more separate stages, valuing first the attributes/criteria, and then evaluating the options against those criteria. However, some approaches, conjoint analysis for example, infer the attribute values implicitly from choices expressed between options possessing different ‘levels’ of the various attributes. With aggregated scores, the attribute weights are predetermined by the scales used to score performance on each attribute.

However, in practice, single‐stage approaches are often used, even when valuing multi‐attribute options, such as treatments or packages of care. Other exercises invite the public to value attributes such as access, waiting times, friendliness of staff etc., without explicitly incorporating the resulting values into a two‐stage model. Whilst many published studies use multi‐stage methods, the overwhelming majority of projects identified in our survey 48 used single‐stage evaluation. However, most methods of eliciting values explicitly are applicable both to single‐stage models and to the individual stages of multi‐stage models.

Constrained versus unconstrained choices

Techniques for eliciting values either require respondents to make constrained (or forced) choices which ‘incorporate some notion of sacrifice’ 49 or allow unconstrained choices or valuations. The latter are characterized by scaling, scoring and rating methods, where each criterion, attribute or option is valued independently of the others (although the effect of constrained choice can be obtained by subsequent normalization – rescaling a respondent’s values so that they sum to 1). Constrained choices involve some form of trade‐off between different attributes or alternatives and include a wide range of voting, ranking, comparison and trade‐off techniques.

Generally, if the attributes or options being valued are independent and not in competition, unconstrained‐choice methods are preferred – not all values involve trade‐offs. For psychological reasons, unconstrained‐choice methods might also be appropriate where attributes, such as equity and access, are being valued, even if subsequent normalization effectively constrains choices. Constrained‐choice methods are indicated where options are in competition and/or the purpose of the exercise is to introduce respondents to the concept of trade‐off or sacrifice. However, if options are mutually exclusive, some constrained‐choice methodologies, such as budget pie, do not work. Unconstrained valuations can cause specific problems in aggregation, especially in relation to inter‐person equity.

Even where options are in competition, unconstrained choices may be appropriate depending on the objectives of the public involvement exercise. Consider, for example, the choice between a night‐sitting service for the elderly to relieve carers and a neighbourhood walk‐in child clinic. To the parent of young children who is also a carer of an elderly person both options may be highly, and equally, valued, whilst a person with no such commitments may rate both options as equally low‐valued. A constrained choice, forcing them to trade off the options and giving both respondents equal ‘voice’, may be appropriate if the user involvement is being viewed as a ‘voting’ exercise. However, if the aim is to determine the relative importance to the community of each service – to determine, say, how many people will be positively affected – it may be more appropriate to ask respondents, using scaling, scoring or rating, to ‘value’ the importance to them of each service independently.

Intensity of preference

Generally, permitting respondents to indicate the intensity of their preference, using methods such as scaling and rating or budget pie, is preferred. But, where the objective is to force choices between two or more options, indication of intensity of preference may be inappropriate. Methods such as single and multiple vote force specific ‘intensify of preference’ values on to respondents, which may not accord with their values. For instance, a multiple‐vote method might invite respondents to indicate their top four choices, thus forcing them to allocate an identical 25% of their ‘vote’ to each of the four, and 0% of their vote to their fifth choice, regardless of how close its value is to their fourth choice.

Dangers can also arise where values are subsequently imposed on the respondent’s choices, which the respondent may not be aware of, e.g. assigning ‘scores’ to responses on a Likert scale, thus imposing equal intervals and fixed intensity of preference scores on the responses. Special problems can arise with ranking when the ordinal rank positions are converted into cardinal scores (i.e. giving the first choice a score of 1, the second a score of 2, etc.). This assumes respondents consider the options equally spaced and implicitly imposes an intensity of preference score on their choices. Rank positions are sometimes reversed before converting to scores, i.e. the top‐ranked item out of 10 is scored 10 and the lowest 1 (or sometimes 9 for the top item and 0 for the bottom – the Borda Count). 50 , 51 In this case, subsequent manipulation additionally treats the scores as if they have ratio properties. However, by implying that the top‐ranked item is valued at 10 times the bottom‐ranked item, study results have suggested far greater differences in the relative value of options than were justified by the actual preferences of the respondents. In addition, as discussed below, aggregation of rank‐position scores can lead to problems.

Money

Methodologies which employ money, such as some variants of budget pie and willingness‐to‐pay (WTP), can encounter specific problems. Willingness‐to‐pay approaches can face respondent resistance or under‐valuation where WTP is being sought for services which are normally provided free at the point of use. Further, despite some imaginative attempts, 52 the problem of the effect of individual respondents’ differential personal purchasing power has not been satisfactorily resolved. In addition, although WTP appears to be the archetypal constrained method involving ‘notions of sacrifice’, when it is used to value publicly provided services, respondents’ choices are constrained only by their own personal disposable income, not by a constrained public budget.

Budget Pie and its two‐option variant, constant‐sum paired comparison, overcome these problems as respondents are allocated a ‘budget’. However, when the budget is allocated in the form of cash, its absolute size raises problems. Realistic sums for health care options are probably outside the normal experience of respondents. Small sums, say £100, risk seeming trivial. Experience suggests that budget‐pie methods work better when respondents are given tokens or points to allocate, rather than money.

Aggregation

Aggregation of the values of individual respondents poses potentially insoluble ethical and theoretical problems. At the simplest ethical level, is it legitimate to combine one person’s rating of 10 with another’s rating of 0 and conclude that the group or societal rating is 5? The theoretical debate takes us into the field of social welfare and social choice and has generated a vast literature. Views range from the impossibility of making interpersonal comparisons of utility, through arguments that aggregating values across individuals is impermissible, to the view that societal choices have to be made – using the example of voting in elections – so we should stop arguing and simply add up the individual values. Whilst the latter argument has some force, the theoretical literature should not be ignored.

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem 53 shows that there is no way to aggregate individual choices that satisfies a set of minimum conditions and axioms. This set includes transitivity (discussed below), non‐dictatorship (no individual’s preferences are imposed as the societal preferences) and the weak Pareto criterion (if all individuals prefer x to y, then society must prefer x to y). 53 Possibly of greatest interest in the NHS, given the proliferation of ranking exercises, is Arrow’s third condition –The Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives. 53 This requires that the preference ordering of a set of alternatives is unaffected by the addition (or subtraction) of an ‘irrelevant’ alternative, i.e. if A is preferred to B and B is preferred to C, the introduction of an ‘irrelevant’ alternative D should not alter the ABC ordering, wherever D itself is placed in the ordering. It is easy to demonstrate how this condition can be violated when rank positions are converted to scores and summed across respondents.

Condorcet’s Voting Paradox 54 , 55 demonstrates that aggregation of individuals’ transitive preferences can yield intransitive ‘group’ preferences; thus, even if every individual has transitive preferences (i.e. if they prefer x to y and y to z, then they prefer x to z), when the individual preferences are aggregated it is possible that the group preferences are intransitive (i.e. the group prefers x to y, y to z, but prefers z to x). 54 , 55

This should not be dismissed simply as theoretical game‐playing. Ranking is used widely within the UK NHS for eliciting values with the rank positions frequently being converted to ‘scores’ and summed. The potential for manipulating results, whether intentionally or inadvertently, by including irrelevant options must be recognized. Further, the method of aggregation can affect the result. As Weale points out:

The same set of preferences in a community amalgamated by a different voting rule will yield a different collective choice. 56

At the very least, those employing techniques should be aware of the dangers of aggregation and of the implications of different methods. Perez 57 agreeing that there is no truly satisfactory procedure for the aggregation of preferences in ordinal contexts, suggests that a framework should be devised to help choose a relatively good rule for a given situation. In addition, because of the problems associated with aggregation, it is often better to avoid single aggregated measures and present, instead, the full distribution of results, using bar‐charts or histograms.

Aggregation also raises issues of inter‐respondent equity. Several techniques, such as voting and budget pie, give respondents equal weight unless a deliberate choice is made to award unequal numbers of votes or unequal budgets. However, with scoring or rating or where, for instance, rank positions are summed but not all respondents rank the same number of options, respondents may unintentionally acquire unequal weights. This may be desirable in some applications but it is important to prevent accidental inter‐respondent inequity.

Ease of use and transparency

Whilst is it desirable that techniques are easy to use for respondents, whether or not such techniques should be transparent – in the sense that respondents can see how their responses are going to be used and how they contribute to the final scores – will depend on the application. Whilst there must be a presumption in favour of transparency, lack of transparency may sometimes be an essential part of the research process. Further, transparency could lead to strategic voting.

Clearly, researchers should understand the techniques used, their implications and, in particular, how the final scores are produced and their interpretation. Dangers can arise from the use of computer software, which permits researchers to employ methodologies which they do not fully understand. There is considerable evidence within the NHS that the implications of some of the methodologies employed are not fully understood.

Choice of technique for eliciting values

A major question is how necessary it is to be concerned with the theoretical bases of techniques. Although some researchers argue it is essential that techniques are grounded in the theory of their own discipline, it is proposed here that a more pragmatic stance be adopted. Thus it is suggested that the questions in Table 3 should be asked when considering the appropriateness of techniques for a particular application. An approach which is ideal in one situation may prove totally inappropriate or misleading in another.

Table 3.

Questions to be asked of techniques

Such a pragmatic stance has long‐standing support. For instance, Huber 58 demonstrating that different methods of eliciting values are equally good predictors of clients’ preferences, concluded that transparency is important and that the major choice criterion should be acceptability of the method to the client. Clark suggests that ‘one good principle is to utilize instruments only as precise and complex as necessary for the decision at hand’, adding that ‘the instruments can be no more sensitive than their users’. 59

However, the choice of method is not unimportant. In a small‐scale study, comparing budget pie, which permits expression of intensity of preference, with multiple vote, which does not, Mullen demonstrated that very different individual and aggregated group values resulted. 60

Conclusion

Attempting to determine the method of value‐elicitation from reports of studies in the public domain involves considerable detective work and, in some cases, the actual method can only be guessed at. Regrettably, in some cases this lack of transparency appears to be deliberate in order to facilitate commercial exploitation, but in other cases it appears to be accidental. If all authors, world‐wide, explained their methods clearly and/or provided full details of their research instruments to enquirers, some re‐invention of the wheel might be prevented and valuable resources diverted to improving methods for involving the public and eliciting and aggregating their values.

A large number of methods are available, both in the literature and in practice, and some have been reviewed here. However, in selecting a method, as well as addressing the questions suggested in Table 3, it is important to ask how necessary it is to be concerned about technical validity. The answer must lie partly in the purpose of such projects. If the public involvement process is the prime objective – and there are repeated reports of the benefit gained from the process itself – then methodological validity is of secondary importance. However, if the results obtained are used to determine (or even inform) priorities and resource redeployment, it would appear essential to have regard for methodological validity and ensure that investigators understand the implications of the methods employed.

These points were stressed many years ago by Hoinville & Courtenay 61 who after 10 years of conducting public consultation exercises concluded that there is no single technique or easy solution:

Measurements have to be tailored to the application to which they will be put. Questions must be as closely linked as possible to the way the answers will be used.

References

- 1. Grimley Evans J. Health care rationing and elderly people. In: Tunbridge M. (ed.) Rationing of Health Care in Medicine. London: Royal College of Physicians of London, 1993: 50.

- 2. Feuerstein MT. Community participation in evaluation: problems and potentials. International Nursing Review, 1980; 27 (6): 187 187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnstein S. A ladder of citizen participation in the USA. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 1969; 35: 216 224. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mullen PM, Murray‐Sykes K, Kearns WE. Community health council representation on planning teams: a question of politics. Public Health, 1984; 98 (2): 143 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mullen PM. Is it necessary to ration health care? Public Money and Management, 1998; 18 (1): 52 58. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mullen PM. Rational rationing? Health Services Management Research, 1998; 11 (2): 113 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bowling A, Jacobson B, Southgate L. Explorations in consultation of the public and health professionals on priority setting in an inner London health district. Social Science and Medicine, 1993; 37 (7): 851 857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart J, Kendall E, Coote A. Citizens’ Juries. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 1994.

- 9. Lenaghan J, New B, Mitchell E. Setting priorities: in there a role for citizens’ juries? British Medical Journal, 1997; 312 (7064): 1591 1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunkerley D & Glasner P. Empowering the public? Citizens’ juries and the new genetic technologies. Critical Public Health, 1998; 8 (3): 181 192. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richardson A. Determining priorities for purchasers: the public response to rationing within the NHS. Journal of Management in Medicine, 1997; 11 (4): 222 232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clark TN. Can you cut a budget pie? Policy and Politics, 1974; 3 (2): 3 31. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clark TN. Modes of collective decision‐making: eight criteria for evaluation of representatives, referenda, participation and surveys. Policy and Politics, 1976; 4: 13 22. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hauser JR & Shugan SM. Intensity measures of consumer preference. Operations Research, 1980; 28: 278 320. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown CV & Jackson PM. Public Sector Economics Oxford: Martin Robertson, 1978.

- 16. Strauss RP & Hughes GD. A new approach to the demand for public goods. Journal of Public Economics, 1976; 6: 191 204. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dodgson CL, (Lewis Carroll). A discussion of the various methods of procedures in conducting elections. (Privately printed in Oxford in 1873). Reprinted in: Black D. (ed.) The Theory of Committees and Elections Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958.

- 18. Hoinville G & Courtenay G. Measuring consumer priorities. In: O’Riordan T, D’Arge RC (eds) Progress in Resource Management and Environmental Planning, Vol. 1. Chichester: Wiley, 1979: 143–178.

- 19. Linstone HA & Turoff M. (eds) The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. New York: Addison‐Wesley Publishing Company, 1975.

- 20. Hauser JR & Shugan SM. op.cit.

- 21. Churchman CW & Ackoff RL. An approximate measure of value. Operations Research, 1954; 2 (2): 172 181. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saaty TL. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 1977; 15 (3): 234 281. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saaty TL. That is not the analytic hierarchy process: what the AHP is and what it is not. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, 1997; 6 (6): 324 335. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ryan M. Using Consumer Preferences in Health Care Decision Making: the Application of Conjoint Analysis, London: Office of Health Economics, 1996.

- 25. Dolan P, Gudex G, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade‐off methods: results from a general population study. Health Economics, 1995; 5 (2): 141 154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drummond MF, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 1987.

- 27. O’Brien B & Viramontes JL. Willingness to pay: a valid and reliable measure of health state preference? Medical Decision Making, 1994; 14 (3): 288 297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donaldson C, Farrar S, Mapp T, Walker A, Macphee S. Assessing community values in health care: is the willingness to pay method feasible? Health Care Analysis, 1997; 5 (1): 7 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bryson N, Ngwenyama OK, Mobolurin A. A qualitative discriminant process for scoring and ranking in group support systems. Information Processing and Management, 1994; 30 (3): 389 405. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelly GA. A Theory of Personality: the Psychology of Personal Contracts, New York: Norton, 1963.

- 31. Knox PL. Regional and local variations in priority preferences. Urban Studies, 1977; 14: 103 107. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoinville G & Courtenay G. op.cit.

- 33. Hoinville G & Courtenay G. op.cit.

- 34. Mullen PM & Spurgeon P. Priority Setting and the Public. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1999.

- 35. Strauss RP & Hughes GD, op.cit.

- 36. Honigsbaum F, Richards J, Lockett T. Priority Setting in Action: Purchasing Dilemmas Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1995.

- 37. Heginbotham C, Ham C, Cochrane M, Richards J. Purchasing Dilemmas London: King’s Fund, 1992.

- 38. Courtenay G & Field J. South Yorkshire Structure Plan – Public Attitude Survey London: Social & Community Planning Research, 1975.

- 39. Whitty P. What Are Colchester People’s Priorities for Health Care? A Population Survey in Urban Colchester Colchester: North Essex Health Authority, 1992.

- 40. Whitty P. op.cit.

- 41. Bowling A. What People Say About Prioritising Health Services London: Kings Fund Centre, 1993.

- 42. Camasso MJ & Dick J. Using Multi‐attribute utility theory as a priority‐setting tool in human services planning. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1993; 16 (4): 295 304. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dolan JG & Bordley DR. Involving patients in complex decisions about their care – an approach using the analytic hierarchy process. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1993; 8 (4): 204 209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dolan JG & Bordley DR. Isoniazid Prophylaxis – the importance of individual values. Medical Decision Making, 1994; 14 (1): 1 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dolan JG. Are patients capable of using the analytic hierarchy process and willing to use it to help make clinical decisions? Medical Decision Making, 1995; 15 (1): 76 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stimson DH. Health agency decision making: an operations research perspective. In: Arnold MF, Blankenship LV, Hess (eds.) Administrative Health Systems: Issues and Perspectives, Chicago: Aldine Atherton, 1971: 395– 433.

- 47. Dickinson AL. Getting the best value from additional resources. Hospital and Health Services Review, 1979; 75: 127 129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mullen PM & Spurgeon P. op.cit.

- 49. Shackley P & Ryan M. Involving consumers in health care decision making. Health Care Analysis, 1995; 3 (3): 198 198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McLean I. Public Choice Oxford: Blackwell, 1987:162 162.

- 51. Bonner J. Politics, Economics and Welfare Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books, 1986: 81 81.

- 52. Donaldson C. Distributional Aspects of Willingness to Pay Aberdeen: Health Economists Study Group, 1995.

- 53. Arrow KJ. Social Choice and Individual Values (2nd edn). New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963.

- 54. Brown CV & Jackson PM. op.cit.: 72 74.

- 55. McLean I. op.cit.: 26 26.

- 56. Weale A. The allocation of scarce medical resources: a democrat’s dilemma. In: Byrne P (ed.) Medicine, Medical Ethics and the Value of Life. Chichester: Wiley, 1990: 122 122.

- 57. Perez J. Theoretical elements of comparison among ordinal discrete multi‐criteria methods Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, 1994; 3 (3): 157 176. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huber GP. Multi‐attribute utility models: a review of field and field‐like studies. Management Science, 1974; 20 (10): 1393 1402. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Clark TN. op.cit.: 26 26.

- 60. Mullen PM. Delphi‐type studies in the health services: the impact of the scoring system. Research Report 17. Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, 1983.

- 61. Hoinville G & Courtenay G. op.cit.: 175 175.