Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether the willingness of the general population to undergo a screening test of questionable effectiveness for pancreatic cancer is influenced by the quality and the extent of the information provided.

Design

Randomised study.

Setting

Switzerland.

Participants

Representative sample (N=1000) of the general population aged over 20.

Interventions

Participants were randomly allocated into two groups (N=500 each), with one group to receive basic and the other extended quality of information. The information was presented in two hypothetical scenarios about implicit and explicit benefits and adverse events of the screening test. Response rates were, respectively, 80.2% (N=401) and 93.2% (N=466).

Main outcome measures

Stated willingness to undergo the screening test.

Results

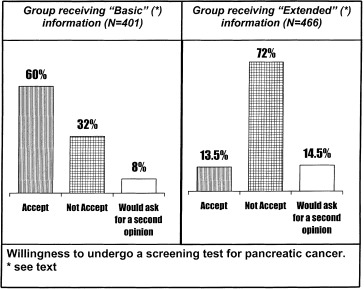

Out of the 401 participants receiving the basic information scenario, 241 (60%) stated their willingness to accept the test, as compared to the 63/466 (13.5%) exposed to the extended one (P < 0.001). After adjusting for respondent characteristics through a logistic regression model, the ‘information effect’, expressed in terms of odds‐ratio (OR), shows that provision of additional information was related to a 91% (OR 0.09; 95CI: 0.07 – 0.13) relative reduction in the likelihood of accepting the screening test.

Conclusion

The quality and the extent of the information provided about the implicit and explicit benefits and adverse events on hypothetical scenarios of a screening test may dramatically change the willingness of people to participate in the testing. This study suggests that provision of full information on the yield of health care interventions plays an important role in protecting the public from being exposed to procedures of questionable effectiveness.

Keywords: community, consumer, EBM, information, pancreatic cancer, public health, screening, Switzerland

Introduction

Over the last few years there has been an increasing consensus in the consideration that patient preferences should play an essential role in clinical decision‐making. 1 Indeed, patient autonomy tends to be acknowledged as a value per se. However, the basic requirement is the provision of adequate information on the yield of the health care intervention proposed. From the consumer side, a desire for health translated into service consumption implies a demand for information about effectiveness, adequacy, risks and benefits and possible alternatives. Lack of knowledge about these aspects causes a certain amount of anxiety in consumer‐patients about making a wrong decision, which could have adverse health outcomes. 2 Without an adequate level of relevant information, the patient tends to accept every procedure proposed not only to maximize health benefits but also (in particular for diagnostic and screening services) to ‘minimize regret’. The latter could be a rational choice caused by uncertainty due to lack of information relevant for decision‐making. 3

While Wolf already showed that giving patients balanced information can change their intention to undergo screening tests for prostate cancer, 4 we explored whether the same holds true when the target is not the individual in a real patient‐doctor encounter, but the general population at large exposed to generic information, as is usually the case for messages conveyed through public health interventions.

Methodology

In May 1998 a mailed questionnaire was sent to a representative sample (N=1000) of the Swiss general population aged over 20 (a stratified random selection of the sample made by a market research company) drawn from the general population register. Participants were randomly allocated to two groups (N=500 each) to receive either basic or extended information about a screening test for pancreatic cancer and were asked to express their willingness to accept the screening procedure. Response rates were, respectively, 80.2% (N=401) and 93.2% (N=466).

The questionnaire included information on the participants’ personal characteristics (age, gender, level of education, first language, having recent experience of cancer among relatives and friends) and attitudes toward medicine in general and relationship with physicians (see footnotes on Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents

Pancreatic cancer was chosen because (1) it affects both sexes; (2) a blood test kit with poor sensibility and specificity is available (tumour marker CA 19.9); (3) the incidence of the disease is relatively low; and (4) the survival at 5 years is very poor.

The two scenarios (basic and extended) provided to the two groups of respondents were:

Basic information scenario:‘During a routine consultation the doctor asks you if you are willing to accept a diagnostic test (consisting of a simple blood examination) in order to identify early whether you have pancreatic cancer (that means that the disease will be identified before you experience any symptoms)’.

Extended information scenario: in addition to the basic information the respondents of this group were provided with the following:

‘The doctor informs you also that: (1) the test is not very accurate, only 30% of those testing positive have pancreatic cancer; (2) as a consequence, all those testing positive will have to undergo additional examinations (including MRI) in order to confirm the diagnosis of cancer. This will require admission to hospital; (3) every year in Switzerland about 11 persons in every 100 000 have a confirmed diagnosis of pancreatic cancer; (4) pancreatic cancer is practically incurable (out of 100 diagnosed only 3 are still alive at five years)’.

Respondents could choose among the following options: (1) I am willing to accept to undergo the test; (2) I will not accept; (3) before making a decision I will ask for a second opinion.

Univariate analyses were performed to assess the relationship between acceptance of the proposed test and participants’ characteristics and attitudes (Table 1).

We assessed the extent to which differences in proportions were due to chance alone using the chi‐square test, and P‐values below 0.05 were considered significant. A multivariate logistic regression model was then used, with acceptance of the proposed screening test (yes=1, no=0) as the dependent variable, and participants’ personal characteristics and attitudes emerging significant in univariate analyses (age, sex, level of education, first language, type of doctor–patient relationship) as predictive variable. The associations were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The analyses were carried out with SPSS/PC statistical package.

Results

As expected only 63/466 (13.5%) of those receiving the extended information stated their willingness to accept the test, as compared to the 241/401 (60%) exposed to the basic one (P < 0.001) (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Willingness to undergo a screening test for pancreatic cancer.

After adjusting for respondents’ characteristics through a logistic regression model (see Table 2), allowing the expression of the ‘information effect’ in terms of odds‐ratio, provision of additional information was related to a 91% (OR 0.09; 95CI: 0.07 – 0.13) relative reduction of the odds of accepting the diagnostic test. Some personal characteristics appeared to be related to the acceptance of the test, regardless of the amount of information provided. In particular, males were more likely to report their willingness to accept (OR 2.19; 95%CI: 1.52–3.16) as well as those with a passive (OR 3.57; 95%CI: 1, 74–7, 31) or collaborative doctor–patient relationship (OR 2.00; 95%CI: 1.09–3.68). Those with German as their first language were also less willing to accept (OR 0.54; 95%CI: 0.36–0.80). The respondents’ level of education was not related to willingness to be tested.

Table 2.

Results of the logistic regression model assessing the effect of different scenarios of information on willingness to accept a screening test for pancreatic cancer

Comment

These results clearly show that willingness to accept to undergo a test of questionable value is affected by whether or not the public has been exposed to an extended level of information, despite not being personalized as is usually the case during a medical consultation. While it remains to be empirically demonstrated that our findings hold true in a real life situation, in this study, when confronted with hypothetical scenarios, about 80% of individuals who would have agreed to undergo the test when exposed to basic information would change their minds after knowing more about the clinical implications of the test.

This shows that the content of information released is essential to over‐ or underestimate the real risk, as Viscusi has pointed out for smoking and lung cancer. 5

Nevertheless, the high proportion (60%) of those receiving basic information agreeing to undergo a screening procedure for a rare cancer with very poor outcome is also of concern. It shows how many consumers may act uncritically when faced with proposed diagnostic procedures, possibly due to over‐optimistic expectations.

Thus both institutions and doctors have a primary responsibility to provide the public and individuals with relevant evidence‐based information. This could have two desirable effects: (1) to make consumers‐patients more aware of the true clinical effectiveness of interventions proposed, and thus less exposed to the risk of accepting procedures of questionable value and (2) to allow informed choices that are most likely to fit with patients’ values, expectations and preferences.

In the face of the impressive increase in numbers of diagnostic procedures, 6 screening tests, 7 and the implementation of predictive medicine in the near future, it is essential to develop a global strategy to enable a more active consumer role in clinical decision making, even among those who, because of their cultural attitudes, are more prone to rely completely on the subjective opinion of their own doctor. Provision of comprehensive research‐based information can maximize patient freedom and autonomy in decision‐making, allowing a true ‘informed’ consent, minimizing the use of inappropriate or questionable diagnostic procedures and avoiding waste of resources.

From a public health perspective, these results highlight the need for community interventions aimed at empowering and encouraging the public to ask physicians the ‘right’ questions before undergoing any suggested procedure. 8 Such a programme is currently ongoing in the Swiss region of Ticino where, through a booklet targeting all households, 9 the consumer‐patient is prompted to ask the physician the following questions before undertaking any diagnostic test:

(1) Which disease (or illness) can you detect using the diagnostic test proposed?

(2) What are the probabilities that you will not get a false‐positive or false‐negative result?

(3) Is the disease (or illness) you can detect curable? And what are the probabilities of success?

There is already some empirical evidence that this approach can be successful. In 1984 a public information campaign in Canton Ticino (Switzerland) decreased hysterectomy rates by 26%. 10

In practical terms, it is feasible to develop, at least for the more frequently performed screening tests, a minimum set of evidence‐based information that the physician should deliver to each patient, allowing time to reflect before giving the informed consent.

Finally, these findings imply that the content of the currently produced leaflets and supports aimed at promoting community screenings should be carefully reviewed and critically assessed, to minimize the potential risk of misguiding the consumer‐patient. 11 , 12 In fact, key messages to promote screening attendance usually emphasize benefits (often overestimated and always presented in a public health perspective) and hardly ever mention adverse events. A more balanced approach is essential to ensure a truly informed choice at the individual level. 13 , 14

Acknowledgements

We are particularly grateful to professor Alberto Holly, Faculty of Economics, University of Lausanne and to Christine Bouchardy, MD, Cancer Registry of Canton of Geneva for useful comments on the manuscript and (C.B.) for providing Swiss estimates of incidence and survival data for pancreatic cancer.

References

- 1. Entwistle VA, Sheldon TA, Sowden A, Watt IS. Evidence‐informed patient choice. Practical issues of involving patients in decisions about health care technologies. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 1998; 14 : 212 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGuire A, Henderson J, Mooney G. The economics of health care: Health care as an economic commodity London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1988.

- 3. Bell DE. Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operational Research, 1982; 30 : 961 981. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wolf AM. Impact of informed consent on patient interest in prostate‐specific antigen screening. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1996; 156 : 1333 1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Viscusi WK. Smoking: Making the Risky Decision Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- 6. Black WC & Welch HG. Advances in diagnostic imaging and overestimation of diseases prevalence and the benefits of therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 1993; 17 : 1237 1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Preventive Services Task Force . Guide to Clinical Preventive Services Alexandria: International Medical Publishing, 1996.

- 8. Domenighetti G, Grilli R, Liberati A. Promoting consumers’ demand for evidence‐based medicine. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 1998; 14 : 97 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dipartimento delle opere sociali . I SI e i NO della Salute Bellinzona: Cantone Ticino, 1998.

- 10. Domenighetti G, Luraschi P, Casabianca A et al Effect of information campaign by the mass media on hysterectomy rates. Lancet, 1988; ii : 1470 1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Foster P & Anderson CM. Reaching targets in the national cervical screening programme: are current practices unethical? Journal of Medical Ethics, 1998; 24 : 151 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slaytor EK & Ward JE. How risks of breast cancer and benefits of screening are communicated to women; analysis of 58 pamplets. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 263 264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coulter A. Evidence based patient information. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 225 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Austoker J. Gaining informed consent for screening. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319 : 722 723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]