Abstract

Background

Schizophrenia is characterized by profound and disabling deficits in the ability to recognize emotion in facial expression and tone of voice. Although these deficits are well documented in established schizophrenia using recently validated tasks, their predictive utility in at-risk populations has not been formally evaluated.

Method

The Penn Emotion Recognition and Discrimination tasks, and recently developed measures of auditory emotion recognition, were administered to 49 clinical high-risk subjects prospectively followed for 2 years for schizophrenia outcome, and 31 healthy controls, and a developmental cohort of 43 individuals aged 7–26 years. Deficit in emotion recognition in at-risk subjects was compared with deficit in established schizophrenia, and with normal neurocognitive growth curves from childhood to early adulthood.

Results

Deficits in emotion recognition significantly distinguished at-risk patients who transitioned to schizophrenia. By contrast, more general neurocognitive measures, such as attention vigilance or processing speed, were non-predictive. The best classification model for schizophrenia onset included both face emotion processing and negative symptoms, with accuracy of 96%, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of 0.99. In a parallel developmental study, emotion recognition abilities were found to reach maturity prior to traditional age of risk for schizophrenia, suggesting they may serve as objective markers of early developmental insult.

Conclusions

Profound deficits in emotion recognition exist in at-risk patients prior to schizophrenia onset. They may serve as an index of early developmental insult, and represent an effective target for early identification and remediation. Future studies investigating emotion recognition deficits at both mechanistic and predictive levels are strongly encouraged.

Keywords: Auditory processing, face processing, prodrome, psychosis

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a major mental disorder that affects about 1% of the population; it is the eighth leading cause of disability worldwide (Mathers et al. 2006). Onset is typically in the second to third decade of life. A critical recent focus, therefore, has been the early detection of individuals at clinical high risk (CHR) for schizophrenia, in order to permit early intervention and, hopefully, prevention. Over the past two decades, criteria have been developed that allow for the recruitment of CHR populations (Miller et al. 2003). Nevertheless, only about 20–30% of individuals meeting present criteria will transition to psychosis within a near-term (<3-year) window, suggesting a need for improved prediction algorithms (Cannon et al. 2008; Ruhrmann et al. 2010; Fusar-Poli et al. 2012a; Nelson et al. 2013).

To date, the strongest and most reliable predictors of transition to psychosis among at-risk individuals are symptom severity (Cannon et al. 2008; Lemos-Giraldez et al. 2009; Ruhrmann et al. 2010; Demjaha et al. 2012; Nelson et al. 2013), particularly of negative symptoms (Velthorst et al. 2009; Demjaha et al. 2012; Piskulic et al. 2012; Nelson et al. 2013; Valmaggia et al. 2013) and subthreshold thought disorder (Klosterkotter et al. 2001; Haroun et al. 2006; Bearden et al. 2011; Demjaha et al. 2012; Kantrowitz et al. 2014; Nelson et al. 2013; DeVylder et al. 2014). While neuropsychological deficits exist in schizophrenia and in at-risk individuals, to date they have not been found to be of value in predicting transition over and above the contribution of symptoms (Seidman et al. 2010; Fusar-Poli et al. 2012b; Lin et al. 2013). Over recent years, there has been increasing focus on social cognition as a distinct dimension of neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia that may be closely related to underlying deficits in sensory function (Butler et al. 2009; Gold et al. 2012; Green et al. 2012; Kantrowitz et al. 2013, 2014). As with other aspects of neurocognition, schizophrenia patients show profound deficits in social cognitive abilities that correlate highly with impaired functional outcome (Green et al. 2012). Moreover, these processes may mature earlier in the course of normal development than more traditional neuropsychological domains, suggesting that they may be especially effective as risk biomarkers (Vicari et al. 2000; Gao & Maurer, 2010; Rosenqvist et al. 2013; Roalf et al. 2014). The present study thus evaluates emotion recognition deficits in CHR individuals as a potential predictor for psychosis outcome over and above general neurocognitive deficit and known predictors such as negative symptoms and subthreshold thought disorder.

The construct of social cognition is operationalized, at least in part, as the ability to recognize emotion based upon facial expression and tone of voice, and is critical for adaptive behavior (Adolphs, 2009; de Waal, 2011; Lemasson et al. 2012). Individuals with schizophrenia show profound and disabling deficits (d = 0.9–1.1) on tests of both face (Kohler et al. 2010) and auditory (Haskins et al. 1995; Leitman et al. 2005; Leitman et al. 2007; Gold et al. 2012; Kantrowitz et al. 2014) emotion recognition. These deficits, moreover, exist early in the course of illness (Edwards et al. 2001; Kucharska-Pietura et al. 2005; Addington et al. 2006, 2008, 2012; van Rijn et al. 2011; Amminger et al. 2012; Thompson et al. 2012; Wolwer et al. 2012; Comparelli et al. 2013; Kohler et al. 2014), suggesting that disturbances may predate psychosis onset. In schizophrenia, face emotion recognition has been assessed with a range of instruments (Edwards et al. 2002). However, over recent years, the Penn Emotion Recognition Test – 40 faces (ER40) has become increasingly adopted as a standard (Taylor & MacDonald, 2012), with consistent deficits of large effect (d = 0.8) across cohorts (Gur et al. 2002; Kohler et al. 2010; Gold et al. 2012; Taylor & MacDonald, 2012). Batteries for assessment of auditory emotion recognition (AER) deficits are less well established, but consistent deficits have been recently demonstrated using a battery initially developed by Juslin and Laukka (Juslin & Laukka, 2001; Leitman et al. 2005; Leitman et al. 2007; Gold et al. 2012; Kantrowitz et al. 2014). To date, the ER40 has been evaluated in CHR individuals only in one cross-sectional study, finding a highly significant deficit comparable with that observed in schizophrenia (Kohler et al. 2014).

This is the first study of which we are aware to apply the present emotion recognition batteries to a prospective CHR cohort. Two prior studies in CHR subjects used different emotion recognition tests, finding mixed results (Addington et al. 2012; Allott et al. 2014). We hypothesized that deficits in emotion recognition would predict psychosis onset in CHR subjects. In addition to evaluating these measures in a CHR cohort relative to our prior studies in schizophrenia, we also estimated in cross-section their age-related trajectory of normal development in a community-based sample (Nooner et al. 2012) to gain insight into the potential time course over which deficits might develop.

Method

Participants

Participants were 49 CHR subjects and 31 healthy controls (HCs) ascertained in metropolitan New York using fliers, mailings of brochures, and Internet advertising. CHR subjects were English speaking, help seeking, and aged 12–30 years, referred from schools and clinicians, or self-referred through the program website. They were ascertained as at CHR for schizophrenia using the traditional criteria of the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes/Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS/SOPS) (Miller et al. 2003). Exclusion criteria included history of threshold psychosis, risk of harm to self or others incommensurate with outpatient care, major medical or neurological disorder, and intelligence quotient (IQ) < 70. Attenuated positive symptoms could not occur solely in the context of substance use or withdrawal, or be better accounted for by another disorder. CHR subjects were followed for up to 2 years and ascertained quarterly in person to determine transition to psychosis. Individuals who did not complete quarterly assessments were contacted by telephone to determine outcome. Additional exclusion criteria for HCs included family history of psychosis, adoption, cluster A personality disorder, and Axis I disorder in the prior 2 years.

An existing cohort of schizophrenia patients (n = 93) (Gold et al. 2012; Kantrowitz et al. 2014) was used for comparison of level of deficit with CHR subjects. Of note, they were not matched for age or gender with the CHR cohort. They were ascertained from in-patient and out-patient facilities at the Nathan Kline Institute (NKI) for Psychiatric Research, with diagnoses established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al. 1993).

A parallel study investigated normative development of face and auditory emotion recognition ability in individuals aged 7–26 years (n = 43) drawn from the Nathan Kline Institute Rockland sample (NKI-RS) (Nooner et al. 2012), a community-ascertained lifespan sample based on zip code recruitment. The sample was 51% male, 51% Caucasian, and had a mean age of 18.2 (s.d.=5.3) years. Mean IQ was 96 (s.d.=15). In this young middle-class sample, Axis I diagnoses [<1%; attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)] and medication use (i.e. 5%; contraception) were rare and 10% had a family history of psychiatric disorder (5% major depression; 2.5% ADHD; 2.5% schizophrenia).

All adults provided informed consent; subjects under the age of 18 years provided assent, with informed consent provided by a parent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University and the NKI for Psychiatric Research. Additionally, means and standard deviations for face emotion recognition (Gur et al. 2002) across age groups from 8 to 21 years in the extended Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort (Gur et al. 2014) (n = 9492) were generously provided in de-identified form by R. C.G. for comparison.

Baseline measures

Prodromal symptoms

Prodromal symptoms were assessed in CHR subjects and HCs using the SIPS/SOPS (Miller et al. 2003), which assesses positive (subthreshold delusions, paranoia, grandiosity, hallucinations and thought disorder), negative (social anhedonia, avolition, experience and expression of emotions, ideational richness and occupational functioning), disorganized and general symptoms. Specifically, subthreshold thought disorder (i.e. conceptual disorganization) was assessed using SIPS P5 and negative symptoms were assessed as the sum of scores for the six negative symptom items. The SIPS/SOPS was administered by trained masters-level clinicians, and ratings were achieved by consensus with the first author (C.M.C.), who was certified multiple times in its administration by investigators at Yale University, and who has maintained good inter-rater reliability with other CHR programs (intra-class correlation coefficients > 0.70 for individual scale items and 1.00 for syndrome ratings). The SIPS/SOPS was also used to determine psychosis outcome prospectively.

Face emotion recognition

Face emotion recognition was assessed using the ER40 (Gur et al. 2002), a valid and reliable measure of face emotion recognition (Taylor & MacDonald, 2012). It uses 40 color photographs of faces expressing four basic emotions – happiness, sadness, anger or fear – plus neutral – with eight photographs for each category, presented in random order. Emotional intensity of facial expressions in the ER40 is categorized as mild or more extreme, each attributed to 20 images. Participants were instructed to choose the correct emotion from among the five listed choices (forced choice) by clicking a computer mouse as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy. Each image was displayed until a choice was made. For each photograph, both the expression and the choice were recorded, such that accuracy (percentage correct) and error patterns (misattribution of emotion, i.e. rates of ‘false positives’) were calculated. Data on the ER40 were available for the CHR cohort, the schizophrenia cohort, the NKI-RS and the Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort (Gur et al. 2012, 2014).

Intelligence

Intelligence was assessed in CHR subjects and HCs using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edn. (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1997) to determine if face emotion recognition deficits could be accounted for by lower full-scale IQ (FSIQ), or its index of processing speed.

Face emotion discrimination

Face emotion discrimination was evaluated using the Penn Emotion Discrimination Task (EMODIFF) (Silver et al. 2002; Gur et al. 2006), which assesses the ability to differentiate the intensity of happiness or sadness in two adjacent images of the same person showing the same emotion. Participants chose one of two faces as more expressive, or decided they were equal. The EMODIFF has 20 trials each for happy and sad faces. Data on the EMODIFF were available for the CHR and schizophrenia cohorts.

Auditory emotion recognition

AER was assessed using 32 audio recordings of native English speakers conveying the same four emotions as the ER40 – anger, fear, happiness, sadness – plus a neutral or ‘no emotion’ stimulus (Juslin & Laukka, 2001; Gold et al. 2012). Data on this task were available for the CHR, schizophrenia and NKI-RS cohorts.

Cognition

Cognition, specifically speed of processing and attention/vigilance, was assessed in the NKI-RS using the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB; Nuechterlein & Green, 2006). The same measure of attention/vigilance (i.e. Continuous Performance Test-Identical Pairs; CPT-IP) was used with the CHR cohort, in whom processing speed was assessed using a computerized Stroop task, for which higher Z scores (adjusted for age and gender) reflect worse performance (Keilp et al. 2013).

Data analysis

Prospective CHR cohort

CHR subjects were stratified for analyses on the basis of eventual transition to psychosis (CHR+ and CHR−), and compared with HCs on demographics, cognition, symptoms, and measures of face and auditory emotion processing, using first parametric [analysis of variance (ANOVA), post hoc Bonferroni pairwise tests] and then non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis analyses, with Mann–Whitney pairwise tests as post hoc group comparisons (further subjected to Bonferroni correction). The ability of face emotion processing to discriminate among groups over and beyond that of attention/vigilance and processing speed was assessed using repeated-measures general linear models, with group as between-subjects and task as within-subjects factors, identifying any significant group × task interactions. Accuracy and misattribution by emotion type, and intensity of facial expression (mild v. extreme), were also explored using repeated-measures general linear models (which are robust to violations of assumptions of normality), with Bonferroni-corrected post hoc group comparisons. In these analyses, group was the between-subjects factor (CHR+, CHR−, HC) and task conditions (i.e. emotion type, intensity) were the within-subjects factors. Effect sizes were interpreted as per Cohen (1992). We set α at 0.05 for all analyses.

Baseline measures that significantly discriminated between CHR+ and CHR− were entered into stepwise logistic regression analyses and assessed for correlation with one another. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with area under the curve (AUC), were established for each identified predictor, with its Youden index calculated as the ‘maximal value for sensitivity + specificity −1’ at the optimal cut-point (Ruopp et al. 2008). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy are reported for each predictor at the optimal cut-point. For comparison with intelligence, mental ages were calculated as the product of IQ/100 and chronological age; deviance from expected intelligence was calculated as the difference between chronological and mental age.

Developmental cohorts

In order to identify the age-equivalence of identified deficits in CHR subjects, we examined in cross-section normal growth curves from childhood to young adulthood in the community-based NKI-RS (Nooner et al. 2012), and for face emotion recognition only, from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort (Gur et al. 2014). The NKI-RS was characterized for cross-sectional normal growth curves of face and auditory emotion recognition, and also for the MCCB (Nuechterlein & Green, 2006) speed of processing and attention/vigilance. We examined the cross-sectional developmental growth curve for each domain, using maximal R2 to fit each model. To compare cross-sectional growth curves, repeated-measures ANOVA was completed with test (ER40, AER, processing speed, attention) as the within-subject factor and age as covariate; simple contrasts were used to compare across tests relative to emotion recognition measures. Accuracy of face emotion recognition in patients and HCs, as assessed with the ER40, was plotted against the neurodevelopmental growth curves obtained from the large (n = 9492) Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort (Gur et al. 2012, 2014), participants aged 8–21 years who were selected at random from the greater Philadelphia area and contacted by mail and then telephone.

Ethical standards

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

Between-group analyses

There were 31 HC and 49 CHR subjects, of whom seven (14.2%) later developed schizophrenia (CHR+) within 2.5 years and 42 did not (CHR−). All CHR subjects met the attenuated positive symptoms syndrome. Outcomes were established primarily by in-person interview, and by telephone if individuals were unable to come to the research program. HC, CHR+ and CHR− groups did not differ by age, gender, ethnicity or IQ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, symptoms and cognition in CHR patients and healthy controls

| Healthy controls (n = 31) | CHR− (n = 42) | CHR+ (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean age, years (s.d.) | 21.4 (3.1) | 20.7 (3.5) | 20.0 (5.2) |

| Age range, years | 15–28 | 13–27 | 14–27 |

| Gender, % male | 65 | 76 | 57 |

| Mean prodromal symptoms (s.d.) | |||

| Positive | 0.9 (1.1) | 12.5 (4.1) | 10.6 (3.9) |

| Subthreshold delusions | 0.3 (0.5) | 3.5 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.7) |

| Subthreshold thought disorder* | 0.1 (0.4) | 2.1 (1.6) | 3.3 (0.8) |

| Negative* | 1.0 (1.5) | 13.9 (6.2) | 20.3 (8.6) |

| Cognition | |||

| n | 24 | 37 | 5 |

| Mean WAIS-III full-scale IQ (s.d.) | 113 (12) | 111 (17) | 108(15) |

| Mean WAIS-III PSI (s.d.) | 102 (16) | 97 (13) | 96 (17) |

| Attention/vigilance, Z score (s.d.) | −0.33 (1.14) | −0.63 (0.99) | −0.39 (0.56) |

| Stroop reaction time, Z score (s.d.) | 0.53 (1.38) | −0.10 (1.96) | 0.85 (1.07) |

CHR, Clinical high-risk; CHR−, CHR participants who did not transition to psychosis; CHR+, CHR participants who transitioned to psychosis; s.d., standard deviation; WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edn.; IQ, intelligence quotient; PSI, processing speed index.

p < 0.05 for CHR+ v. CHR−.

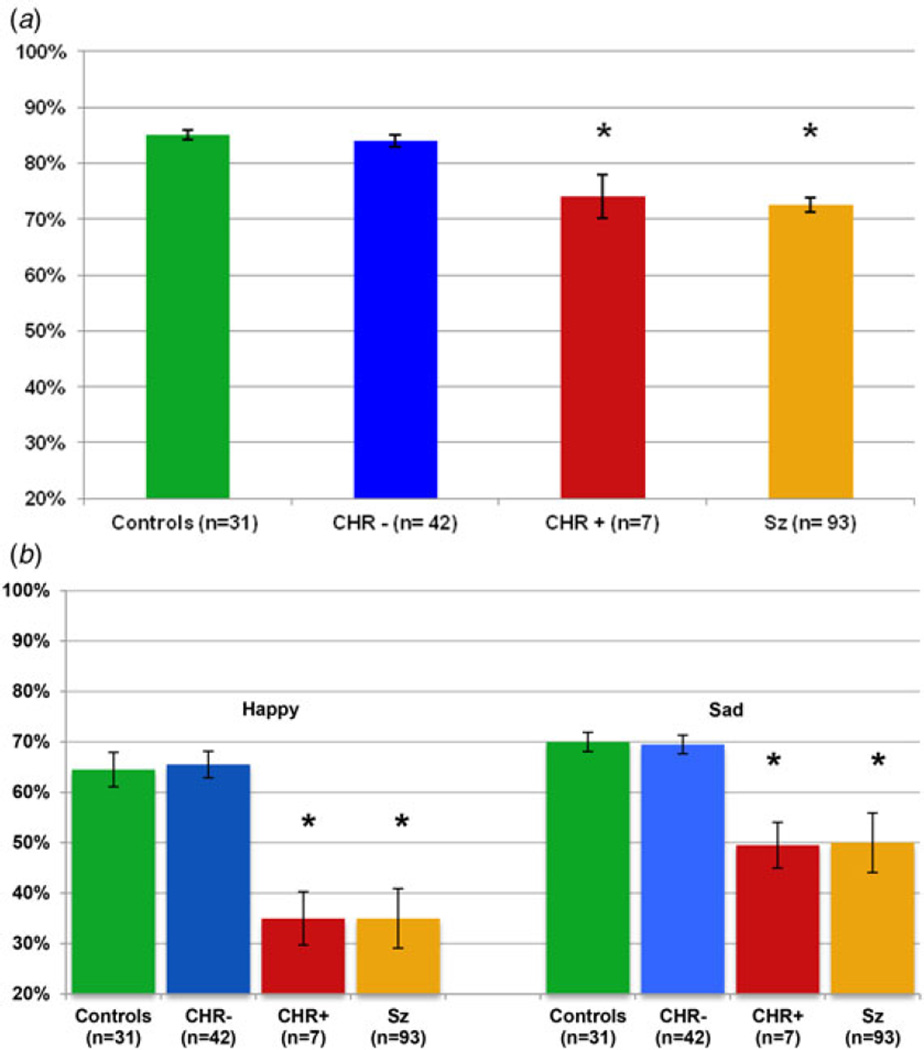

As predicted, baseline accuracy in face emotion processing (i.e. percentage correct) varied significantly across groups for both face emotion recognition (F2,74 = 7.72, p = 0.001, Fig. 1a) and discrimination (F2,74 = 9.33, p < 0.001, Fig. 1b). Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests showed significant differences between CHR+ subjects and both HC and CHR− subjects for both the ER40 and EMODIFF (all p’s ≤ 0.001). By contrast, HC and CHR− subjects were not significantly different (both post hoc p’s = 1.0). No significant differences were observed between CHR+ and CHR− subjects on tests of either attention/vigilance, as measured by the CPT-IP (post hoc p = 1.0) or processing speed as measured by the Stroop task (post hoc p = 0.75) (Table 1). Furthermore, ER40 deficits in CHR− v. CHR+ subjects were differential relative to both attention/vigilance (group × task: F1,40 = 10.2, p = 0.003) and processing speed (group × task: F1,40 = 10.1, p = 0.003), suggesting relative specificity of effect; similar results were found for EMODIFF deficits (both p’s < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Face processing in healthy controls, CHR participants who transitioned to psychosis (CHR+), CHR participants who did not transition to psychosis (CHR−) and schizophrenia patients (Sz) (Gold et al. 2012): face emotion recognition and face emotion discrimination. Percentage accuracy at baseline for (a) the Penn Emotion Recognition Test and (b) the Penn Emotion Discrimination Test. Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. * Mean value was significantly different from those for the controls and the CHR− group (p < 0.05).

Similar statistical results were obtained as well using non-parametric statistics to control for potential outliers. In these analyses as well, highly significant results were obtained for baseline face emotion recognition (χ22 = 9.5, p = 0.009, Fig. 1a) and discrimination (χ22 = 13.5, p = 0.001, Fig. 1b). Specifically, while the full cohort of 49 CHR subjects had no deficits in face emotion recognition (Mann–Whitney U = 596, p= 0.10) or discrimination (Mann–Whitney UU = 673, p = 0.39) as compared with HCs, the CHR+ subjects differed significantly from both HC (ER40, Mann–Whitney U = 30, p = 0.002; EMODIFF, Mann–Whitney U = 16, p < 0.001) and CHR− individuals (ER40, Mann–Whitney U = 55, p = 0.006; EMODIFF Mann–Whitney U = 25, p< 0.001), who were themselves statistically indistinguishable in face emotion processing (both p’s > 0.34) (Fig. 1). Between-group differences for CHR+ with both HC and CHR− subjects were of large statistical effect (d = 0.9), and comparable with that seen in schizophrenia (Fig. 1).

Group × emotion analyses

A secondary analysis evaluated the pattern of deficit across emotions in the ER40 and EMODIFF tasks. For ER40, repeated-measures analyses showed a significant group × emotion interaction for both accuracy (p = 0.04) and mislabeling (p = 0.003). The interaction was driven by significant reductions in baseline accuracy for detection of anger and fear in CHR+ patients relative to both HC and CHR− subjects (both p’s < 0.05) (online Supplementary Fig. S1). The mislabeling of emotionally expressive faces as ‘neutral’ was greater for CHR+ than for CHR− or HC subjects (both post hoc p’s < 0.001). Correspondingly, review of ER40 error patterns in CHR+ subjects showed that ‘false-positive’ labeling of neutral was applied primarily to expressions of fear and anger.

Further, for ER40, CHR+ individuals had decreased accuracy for identification of face emotions of more mild intensity (χ22 = 10.2, p = 0.006), as compared with CHR− (post hoc p = 0.009) and HC subjects (post hoc p = 0.001). By contrast, no difference in accuracy was found for stimuli showing greater intensity of emotion (χ22 = 2.6, p = 0.27). Consistent with this, there was a trend for a group × emotion intensity interaction (F2,77 = 2.9, p = 0.06).

For the EMODIFF, the baseline degree of deficit for CHR+ patients was similar for happy (χ22 = 12.4, p = 0.002) and sad (χ22 = 12.9, p = 0.002, Fig. 1b), with no group × emotion interaction. As in primary analyses, CHR+ subjects differed from both CHR− and HC individuals (all post hoc p’s < 0.001).

Thought disorder and clinical variables

In addition, consistent with prior research, subthreshold thought disorder (χ22 = 35.9, p < 0.001) and total negative symptom severity (χ22 = 50.7, p < 0.001) also varied across groups (Table 1), with CHR+ individuals showing increased severity relative to both CHR− individuals (thought disorder: post hoc p = 0.04; negative symptoms: post hoc p = 0.01) and HC subjects (all post hoc p’s < 0.001). Subthreshold thought disorder was significantly associated with both face emotion recognition accuracy (r = −0.46, p = 0.001) and negative symptoms (r = 0.35, p = 0.02).

Prediction of schizophrenia outcome

Baseline performance on the ER40 alone was able to predict psychosis outcome with 90% accuracy (Table 2), with an AUC of 0.815 for the ROC curve (see online Supplementary Fig. S2). When identified predictors of psychosis were evaluated together in forward stepwise logistic regression, the derived optimal model (−2 log likelihood = 4.7, χ21 = 35.5, p < 0.001) also included negative symptoms and face emotion discrimination, in addition to face emotion recognition, with 96% accuracy and an AUC of 0.99 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of psychosis onset in CHR cohorts

| Predictor | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | YIa | Acc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current study | ||||||

| Best model (ER40, EMODIFF and negative symptoms) | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 0.96 |

| ER40<78% alone | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.64 | 0.90 |

| EMODIFF<60% alone | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| Negative symptoms alone | 0.57 | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.92 |

| SIPS thought disorder >2 alone | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.57 |

| Clinical features: best models in large studies | ||||||

| Genetic risk and social function (n = 291) (Cannon et al. 2008) | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.30 | 0.68 |

| Positive symptoms, poor sleep, schizotypal disorder, poor function, education (n = 183) (Ruhrmann et al. 2010) |

0.42 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| Poor function and longer duration of symptoms (n = 700) (Nelson et al. 2013) |

0.44 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 0.28 | 0.72 |

| Biomarkers | ||||||

| MRI machine learning (n = 73) (Koutsouleris et al. 2015) | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Mismatch negativity (n = 62) (Bodatsch et al. 2011) | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.51 | 0.74 |

| Mismatch negativity (n = 31) (Perez et al. 2014) | 0.33 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.61 |

CHR, Clinical high-risk; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; YI, Youden index; Acc, accuracy; ER40, Penn Emotion Recognition Test – 40 faces; EMODIFF, Penn Emotion Discrimination Task; SIPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

‘Maximal value for sensitivity + specificity −1’ at the optimal cut-point (Ruopp et al. 2008).

Of note, IQ did not account for the predictive value of deficit in face emotion recognition in CHR+ subjects, as it was neither related to face emotion recognition (r = 0.02) nor to schizophrenia outcome (Table 1). Neither ‘mental age’ nor its difference from chronological age was associated with face emotion recognition (all r’s < 0.2; p’s = n.s.). In the CHR cohort, only two subjects (CHR−) had a mental age below adulthood: they had adult levels of accuracy on the ER40 (age 13 years, FSIQ 91, mental age 11.8 years, 82.5% accuracy; and age 17 years, FSIQ 83, mental age 14.1 years, 87.5% accuracy). Likewise, two HCs had a mental age below adulthood: they also nonetheless had adult levels of accuracy on the ER40 (age 14 years, FSIQ 93, mental age 13.0 years, 90% accuracy, and age 17 years, FSIQ 91, mental age 15.4 years, 85% accuracy).

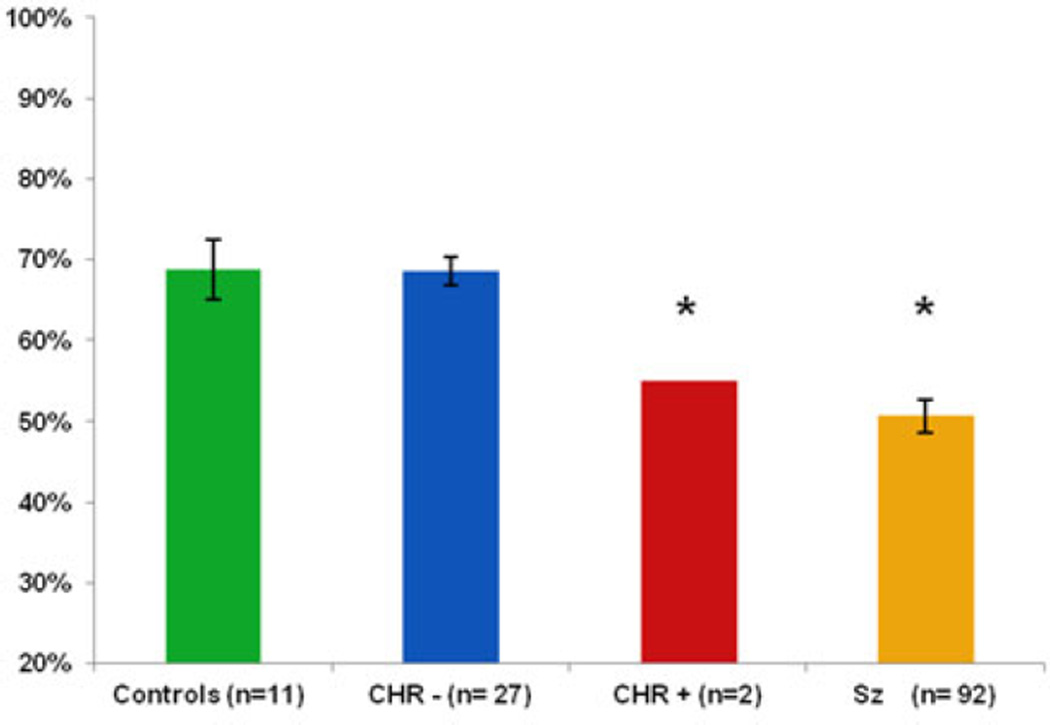

Auditory emotion recognition

Data on baseline AER and tone matching were available for a subgroup of the cohort, i.e. eight HC and 29 CHR subjects, of whom only two developed schizophrenia (Fig. 2). Results from these subjects were therefore compared with published values. Specifically, in a prior study we observed a normative range of mean 65.9 (s.d. = 9.8) in a sample of 188 healthy subjects with mean age of 21.3 years (Gold et al. 2012). Six of the eight current HC and 24 of the 27 CHR− subjects fell within or above this range; by contrast, both CHR+ subjects were significantly impaired and at levels comparable with those previously observed in schizophrenia. Of course, this apparent deficit in AER must be replicated in a larger sample.

Fig. 2.

Auditory emotion recognition in healthy controls, CHR participants who transitioned to psychosis (CHR+), CHR participants who did not transition to psychosis (CHR−) and schizophrenia patients (Sz) (Gold et al. 2012): percentage accuracy at baseline on the Auditory Emotion Recognition Test. Values are means, with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. * Mean value was significantly different from those for the controls and the CHR− group (p < 0.05).

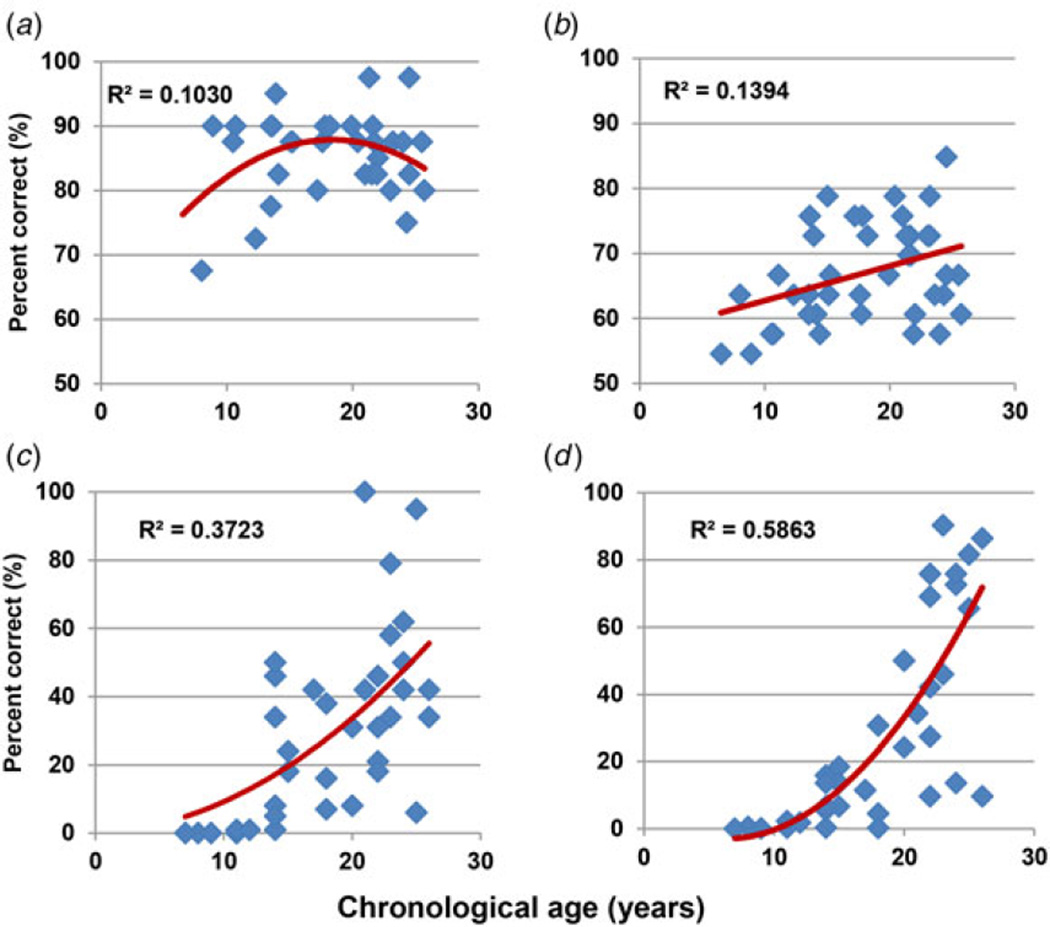

Normal development

In the NKI-RS, adult performance in face emotion recognition was achieved by the age of 14 years, reaching a plateau thereafter. By contrast AER showed a monotonic increase starting before the age of 14 years but then extending into adulthood (r = 0.37, p = 0.02; Fig. 3), suggesting a differential age-related trajectory across the two forms of emotion recognition. By contrast to these measures, both speed of processing and attention/vigilance showed little development before the age of 14 years, but significant increase thereafter, with R2 maximized by an exponential model for both measures (r = 0.64 and r = 0.74, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Correspondingly, in repeated-measures ANOVA, across all four tests, there was a significant task × age interaction (F3,28 = 21.5, p < 0.001). Although the task × age interaction was not significantly different for auditory and facial emotion recognition (F1,30 = 1.21, p = 0.28), trajectories of both were significantly different from both processing speed (F1,30 = 25.3, p < 0.001) and attention (F1,30 = 59.1, p < 0.001). As expected, trajectories of processing speed and attention were not significantly different from each other (F1,30 = 0.0, p = 0.99).

Fig. 3.

Normal development of social and other cognition in the Nathan Kline Institute Rockland sample. Percentage accuracy across ages for (a) the Penn Emotion Recognition Test – 40 faces (ER40), (b) the Auditory Emotion Recognition (AER) Test, (c) Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) speed of processing and (d) MCCB attention/vigilance.

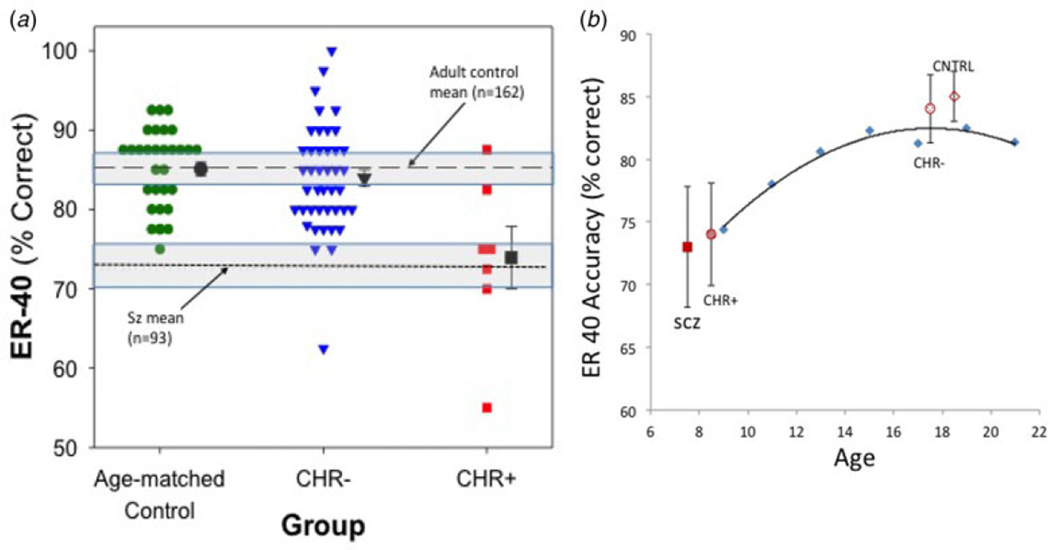

Comparison of clinical and developmental cohorts

When data from the CHR group for face emotion recognition were compared with neurodevelopmental norms (Nooner et al. 2012), mean scores from CHR+ subjects and schizophrenia patients were at or below those observed in 10-year-olds, whereas CHR− subjects and HCs showed age-appropriate performance levels, consistent with the larger Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort (Fig. 4b). By contrast, no reduction was observed in FSIQ, or in tests of processing speed index or attention/vigilance, suggesting maintenance of other neurocognitive functions in CHR+ subjects despite emotion recognition deficits.

Fig. 4.

Face emotion recognition across groups: age-matched controls; clinical high risk (CHR) participants who transitioned to psychosis (CHR+); CHR participants who did not transition to psychosis (CHR−). Percentage accuracy at baseline for the Penn Emotion Recognition Test – 40 faces (ER-40) from Fig. 1 for at-risk groups and age-matched controls (CNTRL), (a) illustrated in a dot plot (as compared with schizophrenia and local populations) and (b) plotted against the cross-sectional developmental growth curve of scores on the same test in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort (courtesy of Holly Moore, Ph.D.). In Fig. 4a, individual data for age-matched healthy controls (circles), CHR− (triangles) and CHR+ (squares) were compared with mean accuracy for adult controls in New York (dashed line) and with schizophrenia patients (Sz; dotted line), both with 95% confidence intervals (shaded area). Similar results were obtained when groups were compared with external norms. In Fig. 4b, mean (s.d.) ER40 percentile accuracy for schizophrenia patient (SCZ) and control groups were mapped along the normal growth curve derived from 9492 children and adolescents in Philadelphia.

Discussion

Early prediction of schizophrenia is critical, so that effective preventive strategies can be developed and implemented. Known predictors of psychosis transition in CHR cohorts include subthreshold thought disorder (Klosterkotter et al. 2001; Haroun et al. 2006; Cannon et al. 2008; Ruhrmann et al. 2010; Bearden et al. 2011; Demjaha et al. 2012; Nelson et al. 2013; DeVylder et al. 2014), negative symptom severity (Velthorst et al. 2009; Demjaha et al. 2012; Piskulic et al. 2012; Nelson et al. 2013; Valmaggia et al. 2013) and sensory processing deficits (Bodatsch et al. 2011; Kayser et al. 2013, 2014; Perez et al. 2014). The present study examined facial and auditory emotion recognition deficits as potential additional predictors of liability for transition to schizophrenia. Emotion recognition deficits are profound in schizophrenia (Haskins et al. 1995; Leitman et al. 2005; Leitman et al. 2007; Kohler et al. 2010; Gold et al. 2012; Kantrowitz et al. 2014) and are evident early in illness (Edwards et al. 2001; Kucharska-Pietura et al. 2005; Addington et al. 2006, 2008, 2012; van Rijn et al. 2011; Amminger et al. 2012; Thompson et al. 2012; Wolwer et al. 2012; Comparelli et al. 2013; Kohler et al. 2014), adding to their potential utility as markers of emergent schizophrenia.

Principal findings of the present study are threefold. First, although CHR subjects as a group were not impaired in face emotion recognition, significant deficits were observed within the subgroup that later developed schizophrenia. In this CHR+ subgroup, deficits evident before psychosis onset were of similar magnitude to those observed in established schizophrenia and significant relative to both HC and CHR subjects who did not develop schizophrenia, supporting its specificity for the illness. Equivalent deficits were observed for face emotion identification and discrimination.

In the present study, measures of general intelligence and neurocognition were not significantly different between CHR+ and CHR− subjects. Of note, in published multicenter studies of cognition in CHR+ v. CHR− subjects (Seidman et al. 2010), the effect size has been found to be about 0.4 s.d. units. Deficits of this magnitude would be significant only with sample sizes much larger than those used in the present study (n > 100). It is therefore noteworthy that significant deficits in the ER40 were observed, corresponding to a large effect-size (0.9 s.d. units) per group. Other measures such as verbal fluency and memory may also distinguish CHR+ from CHR− subjects with a similar effect size of about 0.4 (Fusar-Poli et al. 2012b). Such measures were not included in the present study so their utility relative to the ER40 could not be assessed. Although the number of CHR+ subjects included in the study (7/49 total CHR patients, 14.3% 2-year conversion rate) was relatively small relative to other recent predictor studies (e.g. Meyer & Kurtz, 2009; Nieman et al. 2014; Perkins et al. 2015), emotion recognition represents a critical construct in schizophrenia research and is relatively understudied in CHR patients. Furthermore, the results were statistically robust and survived both Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons and non-parametric statistical analysis to mitigate effects of potential outliers. Furthermore, both the ER40 and EMODIFF are well-validated, easily implementable tasks, so that the present results have potential short-term clinical utility, as well as assisting long term in refining etiological theories of schizophrenia.

Second, in logistic regression analysis, emotion recognition deficits remained as significant predictors over and above general cognition and contributions of other known risk factors including severity of sub-threshold thought disorder (Klosterkotter et al. 2001; Haroun et al. 2006; Cannon et al. 2008; Ruhrmann et al. 2010; Bearden et al. 2011; Demjaha et al. 2012; Nelson et al. 2013; DeVylder et al. 2014) and negative symptoms (Velthorst et al. 2009; Demjaha et al. 2012; Piskulic et al. 2012; Nelson et al. 2013; Valmaggia et al. 2013). Furthermore, as opposed to negative symptoms, which show low sensitivity but high specificity at the point of maximal discrimination, emotion recognition deficits showed higher sensitivity (0.93) than specificity (0.71). Consequently, an optimal model combining both emotion recognition values and suprathreshold negative symptoms (SIPS > 22) showed high values for both sensitivity (0.86) and specificity (0.98) and high (0.96) overall accuracy (Table 2), comparable with or higher than that seen for symptoms alone (Cannon et al. 2008; Ruhrmann et al. 2010; Nelson et al. 2013), though with the caveat that these were not a priori criteria, as had been employed in prior studies such as by Ruhrmann et al. (2010). Our model’s accuracy in predicting psychosis was also comparable with or greater than that observed for risk biomarkers, such as auditory mismatch negativity (Bodatsch et al. 2011; Perez et al. 2014) or neuroimaging patterns (Koutsouleris et al. 2015). Of note, once emotion recognition and negative symptoms were considered, contributions of thought disorder were no longer significant.

Third, using a parallel developmental study – the large Philadelphia Neurodevelopment Cohort, it was demonstrated that levels of face emotion recognition deficits associated with the pre-psychosis state in schizophrenia were equivalent to levels of accuracy reached by the age of 10 years in normal development, supporting the concept that these deficits may be stable pre-morbid features in individuals predisposed to schizophrenia (Dickson et al. 2014). In normal development, face emotion recognition ability is nearly fully developed by the end of early adolescence (Vicari et al. 2000; Gao & Maurer, 2010; Rosenqvist et al. 2013). By contrast, AER (Cohen et al. 1990; Doherty et al. 1999; Morton & Trehub, 2001) and other aspects of neurocognition such as processing speed or attention/vigilance (Roalf et al. 2014) continue to improve throughout adolescence, the age of schizophrenia risk, into adulthood. The earlier normal development of emotion identification in faces (versus speech) may reflect earlier maturation of visual versus auditory or prefrontal brain regions (Hill et al. 2010).

Although emotion recognition deficits are well established across stages of schizophrenia, relatively few studies to date have evaluated their predictive power for psychosis onset in CHR cohorts. An initial prospective study performed by Addington et al. (2012), using tests developed by Kerr & Neale (1993), found no predictive value for emotion recognition deficits, though dropout rates were high at 46% by 6 months and 66% by 12 months. Of note, dropouts were considered non-converters, potentially biasing against detection of transition to psychosis. A more recent study in a primarily female cohort that included placebo-assigned participants in an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids clinical trial, using a modification of Feinberg’s procedure (Feinberg et al. 1986), also did not find decreased overall accuracy in face emotion recognition among CHR+ versus CHR− individuals, but did find significant reduced accuracy in identifying fearful and neutral faces (Allott et al. 2014). In the present battery, the highest predictive value was observed also for sensitivity to fearful and angry faces, partially consistent with the prior CHR study. The decrease in discrimination of negative emotions of fear and anger from neutral expression is consistent with prior cross-sectional studies in schizophrenia and its risk states (Kohler et al. 2003; Premkumar et al. 2008; Eack et al. 2010; Pinkham et al. 2011; van Rijn et al. 2011; Dickson et al. 2014). Similarly, although the number of subjects studied was low, promising results were obtained with our AER battery as a predictor, encouraging further research.

An unanswered question in the present study is the degree to which deficits in emotion processing are related to more basic deficits in early visual and auditory processing (Butler et al. 2009). van Rijn et al. (2011) described deficits in face emotion processing in CHR individuals in the context of otherwise normal basic face perception (van Rijn et al. 2011), suggesting relative preservation of occipital relative to temporal face regions as in schizophrenia (Butler et al. 2008). Furthermore, the present study is consistent with prior work from our group demonstrating impaired form perception on the Rorschach test in CHR individuals relative to HCs (Kimhy et al. 2007), as well as more recent work demonstrating impaired visual reading ability in CHR individuals (Revheim et al. 2014). Over recent years, there has been an increased focus on sensory processing impairments, particularly auditory, in schizophrenia (Javitt, 2009) and CHR individuals (Bodatsch et al. 2011; Kayser et al. 2013, 2014; Perez et al. 2014), and demonstration of predictive value for sensory measures such as auditory mismatch negativity (Bodatsch et al. 2011; Kayser et al. 2014; Perez et al. 2014). To date, studies of emotion recognition and basic sensory function have been conducted in separate investigations. The present study argues for future investigations using parallel sensory and emotion recognition measures.

In addition to their predictive power, it has been proposed that emotion recognition deficits may also play a contributory role in the development of psychosis in CHR individuals. Specifically, difficulties in participating in normal social interaction may lead directly over time to social withdrawal and ‘deafferentation’ (Hoffman, 2007), which are known exacerbating features in early psychosis. To the extent that emotion recognition deficits do contribute directly to development of psychosis, early detection may be critical to permit timely intervention. Recent studies suggest that impaired face emotion recognition may be remediable, with generalization of effect including improved prosody and social function (Wolwer & Frommann, 2011), and normalization of activity in the face-processing network (Habel et al. 2010). Implementation of such efforts during the CHR period may thus be critical for altering long-term course.

A notable finding in this study is the strong correlation between subthreshold thought disorder and face emotion recognition. Both processes have been studied independently but this is the first study to our knowledge to include measures of both within the same CHR sample. At present, the basis for this correlation remains unknown. One potential basis for integration occurs at the level of regional dysfunction, with both emotion recognition (Calder & Young, 2005; Atkinson & Adolphs, 2011; Said et al. 2011) and verbal communication (Rama et al. 2012; Ozyurek, 2014) depending heavily on structures within the superior temporal sulcus (STS), with right STS activity being critical for the detection of features such as face emotion recognition or trustworthiness (Dzhelyova et al. 2011) and the left STS playing a significant role in normal language (Brunetti et al. 2014) and in thought disorder associated with schizophrenia (Horn et al. 2010). A second occurs at the level of shared neurochemical substrates, such that both schizophrenia-like deficits in early visual processing (Javitt, 2009) and thought disorder (Adler et al. 1998) are induced by antagonists of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDAR), suggesting that these impairments may index subthreshold NMDAR dysfunction. Regardless of the underlying mechanism, the significant correlation between these two constructs, which survives co-variation for severity of symptoms or more general neurocognitive dysfunction, argues for further joint investigation to determine shared underlying substrates.

The main limitation in the current study is cohort size and an absence of simultaneous data on physiological measures, such as auditory mismatch negativity, which have also been shown to predict conversion (Bodatsch et al. 2011; Kayser et al. 2014; Perez et al. 2014) and might help to further refine the prediction algorithm. Future studies will entail the assessment in tandem of symptoms, emotion recognition, and neurophysiological measures in order to further refine the risk prediction algorithm and to further understand the early pathophysiological mechanisms of schizophrenia onset.

Conclusion

Although significant improvements have been made over recent years in the development of predictors of transition to psychosis among CHR individuals, established scales such as the SIPS/SOPS are only partially effective. The present study suggests that face emotion recognition ability, which reaches adult levels early in adolescence, may represent a significant additional predictor of conversion, consistent with its known role in predicting impaired outcome in schizophrenia. The present results are consistent also with other recent studies establishing early visual impairment as potential endophenotypes for psychotic disorders (Yeap et al. 2006; Revheim et al. 2014). The present study thus adds to the emergent literature suggesting that sensory-level deficits, including not only deficits in auditory (Bodatsch et al. 2011; Kayser et al. 2014; Perez et al. 2014) and olfactory (Kayser et al. 2013) processing, but also visual-level impairments (Kimhy et al. 2007; Perez et al. 2012; Revheim et al. 2014), may represent critical targets for early detection and intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH086125, R01P50MH086384 and R01P50MH086384 S1) and the New York State Office of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715000902

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Addington J, Penn D, Woods SW, Addington D, Perkins DO. Facial affect recognition in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:67–68. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Piskulic D, Perkins D, Woods SW, Liu L, Penn DL. Affect recognition in people at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;140:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Saeedi H, Addington D. Facial affect recognition: a mediator between cognitive and social functioning in psychosis? Schizophrenia Research. 2006;85:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler CM, Goldberg TE, Malhotra AK, Pickar D, Breier A. Effects of ketamine on thought disorder, working memory, and semantic memory in healthy volunteers. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43:811–816. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:693–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allott KA, Schafer MR, Thompson A, Nelson B, Bendall S, Bartholomeusz CF, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Schlogelhofer M, Bechdolf A, Amminger GP. Emotion recognition as a predictor of transition to a psychotic disorder in ultra-high risk participants. Schizophrenia Research. 2014;153:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Schlogelhofer M, Mossaheb N, Werneck-Rohrer S, Nelson B, McGorry PD. Emotion recognition in individuals at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38:1030–1039. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson AP, Adolphs R. The neuropsychology of face perception: beyond simple dissociations and functional selectivity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 2011;366:1726–1738. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, Wu KN, Caplan R, Cannon TD. Thought disorder and communication deviance as predictors of outcome in youth at clinical high risk for psychosis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodatsch M, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, Muller R, Schultze-Lutter F, Frommann I, Brinkmeyer J, Gaebel W, Maier W, Klosterkotter J, Brockhaus-Dumke A. Prediction of psychosis by mismatch negativity. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti M, Zappasodi F, Marzetti L, Perrucci MG, Cirillo S, Romani GL, Pizzella V, Aureli T. Do you know what I mean? Brain oscillations and the understanding of communicative intentions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8:36. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PD, Abeles IY, Weiskopf NG, Tambini A, Jalbrzikowski M, Legatt ME, Zemon V, Loughead J, Gur RC, Javitt DC. Sensory contributions to impaired emotion processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35:1095–1107. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PD, Tambini A, Yovel G, Jalbrzikowski M, Ziwich R, Silipo G, Kanwisher N, Javitt DC. What’s in a face? Effects of stimulus duration and inversion on face processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;103:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder AJ, Young AW. Understanding the recognition of facial identity and facial expression. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:641–651. doi: 10.1038/nrn1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, Seidman LJ, Perkins D, Tsuang M, McGlashan T, Heinssen R. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Prather A, Town P, Hynd G. Neurodevelopmental differences in emotional prosody in normal-children and children with left and right temporal-lobe epilepsy. Brain and Language. 1990;38:122–134. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(90)90105-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparelli A, Corigliano V, De Carolis A, Mancinelli I, Trovini G, Ottavi G, Dehning J, Tatarelli R, Brugnoli R, Girardi P. Emotion recognition impairment is present early and is stable throughout the course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2013;143:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FB. What is an animal emotion? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1224:191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demjaha A, Valmaggia L, Stahl D, Byrne M, McGuire P. Disorganization/cognitive and negative symptom dimensions in the at-risk mental state predict subsequent transition to psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38:351–359. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder JE, Muchomba FM, Gill KE, Ben-David S, Walder DJ, Malaspina D, Corcoran CM. Symptom trajectories and psychosis onset in a clinical high-risk cohort: the relevance of subthreshold thought disorder. Schizophrenia Research. 2014;159:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson H, Calkins ME, Kohler CG, Hodgins S, Laurens KR. Misperceptions of facial emotions among youth aged 9–14 years who present multiple antecedents of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40:460–468. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty CP, Fitzsimons M, Asenbauer B, Staunton H. Discrimination of prosody and music by normal children. European Journal of Neurology. 1999;6:221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.1999.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhelyova MP, Ellison A, Atkinson AP. Event-related repetitive TMS reveals distinct, critical roles for right OFA and bilateral posterior STS in judging the sex and trustworthiness of faces. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:2782–2796. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2011.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Mermon DE, Montrose DM, Miewald J, Gur RE, Gur RC, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS. Social cognition deficits among individuals at familial high risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:1081–1088. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Pattison PE. Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:789–832. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Pattison PE, Jackson HJ, Wales RJ. Facial affect and affective prosody recognition in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;48:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg TE, Rifkin A, Schaffer C, Walker E. Facial discrimination and emotional recognition in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:276–279. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030094010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Opler LA, Hamilton RM, Linder J, Linfield LS, Silver JM, Toshav NL, Kahn D, Williams JB, Spitzer RL. Evaluation in an inpatient setting of DTREE, a computer-assisted diagnostic assessment procedure. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1993;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, Borgwardt S, Kempton MJ, Valmaggia L, Barale F, Caverzasi E, McGuire P. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012a;69:220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Deste G, Smieskova R, Barlati S, Yung AR, Howes O, Stieglitz RD, Vita A, McGuire P, Borgwardt S. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012b;69:562–571. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Maurer D. A happy story: developmental changes in children’s sensitivity to facial expressions of varying intensities. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2010;107:67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R, Butler P, Revheim N, Leitman DI, Hansen JA, Gur RC, Kantrowitz JT, Laukka P, Juslin PN, Silipo GS, Javitt DC. Auditory emotion recognition impairments in schizophrenia: relationship to acoustic features and cognition. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:424–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11081230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Hellemann G, Horan WP, Lee J, Wynn JK. From perception to functional outcome in schizophrenia: modeling the role of ability and motivation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:1216–1224. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Calkins ME, Satterthwaite TD, Ruparel K, Bilker WB, Moore TM, Savitt AP, Hakonarson H, Gur RE. Neurocognitive growth charting in psychosis spectrum youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:366–374. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Richard J, Calkins ME, Chiavacci R, Hansen JA, Bilker WB, Loughead J, Connolly JJ, Qiu H, Mentch FD, Abou-Sleiman PM, Hakonarson H, Gur RE. Age group and sex differences in performance on a computerized neurocognitive battery in children age 8–21. Neuropsychology. 2012;26:251–265. doi: 10.1037/a0026712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Sara R, Hagendoorn M, Marom O, Hughett P, Macy L, Turner T, Bajcsy R, Posner A, Gur RE. A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2002;115:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, Kohler CG, Ragland JD, Siegel SJ, Lesko K, Bilker WB, Gur RC. Flat affect in schizophrenia: relation to emotion processing and neurocognitive measures. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:279–287. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habel U, Koch K, Kellermann T, Reske M, Frommann N, Wolwer W, Zilles K, Shah NJ, Schneider F. Training of affect recognition in schizophrenia: neurobiological correlates. Social Neuroscience. 2010;5:92–104. doi: 10.1080/17470910903170269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroun N, Dunn L, Haroun A, Cadenhead KS. Risk and protection in prodromal schizophrenia: ethical implications for clinical practice and future research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:166–178. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins B, Shutty MS, Kellogg E. Affect processing in chronically psychotic patients: development of a reliable assessment tool. Schizophrenia Research. 1995;15:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00081-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Inder T, Neil J, Dierker D, Harwell J, Van Essen D. Similar patterns of cortical expansion during human development and evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:13135–13140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001229107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RE. A social deafferentation hypothesis for induction of active schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1066–1070. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn H, Federspiel A, Wirth M, Muller TJ, Wiest R, Walther S, Strik W. Gray matter volume differences specific to formal thought disorder in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2010;182:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. When doors of perception close: bottom-up models of disrupted cognition in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:249–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juslin PN, Laukka P. Impact of intended emotion intensity on cue utilization and decoding accuracy in vocal expression of emotion. Emotion. 2001;1:381–412. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Hoptman MJ, Leitman DI, Silipo G, Javitt DC. The 5% difference: early sensory processing predicts sarcasm perception in schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:25–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Leitman DI, Lehrfeld JM, Laukka P, Juslin PN, Butler PD, Silipo G, Javitt DC. Reduction in tonal discriminations predicts receptive emotion processing deficits in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39:86–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser J, Tenke CE, Kroppmann CJ, Alschuler DM, Ben-David S, Fekri S, Bruder GE, Corcoran CM. Olfaction in the psychosis prodrome: electrophysiological and behavioral measures of odor detection. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2013;90:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser J, Tenke CE, Kroppmann CJ, Alschuler DM, Fekri S, Ben-David S, Corcoran CM, Bruder GE. Auditory event-related potentials and alpha oscillations in the psychosis prodrome: neuronal generator patterns during a novelty oddball task. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2014;91:104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Russell M, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Harkavy-Friedman J, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior: attention control, memory and executive dysfunction in suicide attempt. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:539–551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr SL, Neale JM. Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:312–318. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimhy D, Corcoran C, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Ritzler B, Javitt DC, Malaspina D. Visual form perception: a comparison of individuals at high risk for psychosis, recent onset schizophrenia and chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;97:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterkotter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM, Schultze-Lutter F. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:158–164. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Richard JA, Brensinger CM, Borgmann-Winter KE, Conroy CG, Moberg PJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Calkins ME. Facial emotion perception differs in young persons at genetic and clinical high-risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Research. 2014;216:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Siegel SJ, Kanes SJ, Gur RE, Gur RC. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error pattern. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1768–1774. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:1009–1019. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsouleris N, Riecher-Rossler A, Meisenzahl EM, Smieskova R, Studerus E, Kambeitz-Ilankovic L, von Saldern S, Cabral C, Reiser M, Falkai P, Borgwardt S. Detecting the psychosis prodrome across high-risk populations using neuroanatomical biomarkers. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;41:471–482. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska-Pietura K, David AS, Masiak M, Phillips ML. Perception of facial and vocal affect by people with schizophrenia in early and late stages of illness. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:523–528. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitman DI, Foxe JJ, Butler PD, Saperstein A, Revheim N, Javitt DC. Sensory contributions to impaired prosodic processing in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitman DI, Hoptman MJ, Foxe JJ, Saccente E, Wylie GR, Nierenberg J, Jalbrzikowski M, Lim KO, Javitt DC. The neural substrates of impaired prosodic detection in schizophrenia and its sensorial antecedents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:474–482. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasson A, Remeuf K, Rossard A, Zimmermann E. Cross-taxa similarities in affect-induced changes of vocal behavior and voice in arboreal monkeys. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e45106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos-Giraldez S, Vallina-Fernandez O, Fernandez-Iglesias P, Vallejo-Seco G, Fonseca-Pedrero E, Paino-Pineiro M, Sierra-Baigrie S, Garcia-Pelayo P, Pedrejon-Molino C, Alonso-Bada S, Gutierrez-Perez A, Ortega-Ferrandez JA. Symptomatic and functional outcome in youth at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;115:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Yung AR, Nelson B, Brewer WJ, Riley R, Simmons M, Pantelis C, Wood SJ. Neurocognitive predictors of transition to psychosis: medium- to long-term findings from a sample at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:2349–2360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods, and results for 2001. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL, editors. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006. chapter 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MB, Kurtz MM. Elementary neurocognitive function, facial affect recognition and social-skills in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;110:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman R, Preda A, Epstein I, Addington D, Lindborg S, Marquez E, Tohen M, Breier A, McGlashan TH. The PRIME North America randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. II. Baseline characteristics of the “prodromal” sample. Schizophrenia Research. 2003;61:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton JB, Trehub SE. Children’s understanding of emotion in speech. Child Development. 2001;72:834–843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, Yuen HP, Wood SJ, Lin A, Spiliotacopoulos D, Bruxner A, Broussard C, Simmons M, Foley DL, Brewer WJ, Francey SM, Amminger GP, Thompson A, McGorry PD, Yung AR. Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (“prodromal”) for psychosis: the PACE 400 study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:793–802. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman DH, Ruhrmann S, Dragt S, Soen F, van Tricht MJ, Koelman JH, Bour LJ, Velthorst E, Becker HE, Weiser M, Linszen DH, de Haan L. Psychosis prediction: stratification of risk estimation with information-processing and premorbid functioning variables. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40:1482–1490. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooner KB, Colcombe SJ, Tobe RH, Mennes M, Benedict MM, Moreno AL, Panek LJ, Brown S, Zavitz ST, Li Q, Sikka S, Gutman D, Bangaru S, Schlachter RT, Kamiel SM, Anwar AR, Hinz CM, Kaplan MS, Rachlin AB, Adelsberg S, Cheung B, Khanuja R, Yan C, Craddock CC, Calhoun V, Courtney W, King M, Wood D, Cox CL, Kelly AM, Di Martino A, Petkova E, Reiss PT, Duan N, Thomsen D, Biswal B, Coffey B, Hoptman MJ, Javitt DC, Pomara N, Sidtis JJ, Koplewicz HS, Castellanos FX, Leventhal BL, Milham MP. The NKI-Rockland sample: a model for accelerating the pace of discovery science in psychiatry. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2012;6:152. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF. MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery. Los Angeles, CA: MATRICS Assessment, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ozyurek A. Hearing and seeing meaning in speech and gesture: insights from brain and behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 2014;369:0130296. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez VB, Shafer KM, Cadenhead KS. Visual information processing dysfunction across the developmental course of early psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:2167–2179. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez VB, Woods SW, Roach BJ, Ford JM, McGlashan TH, Srihari VH, Mathalon DH. Automatic auditory processing deficits in schizophrenia and clinical high-risk patients: forecasting psychosis risk with mismatch negativity. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;75:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO, Jeffries CD, Addington J, Bearden CE, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, Mathalon DH, McGlashan TH, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. Towards a psychosis risk blood diagnostic for persons experiencing high-risk symptoms: preliminary results from the NAPLS project. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;41:419–428. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Brensinger C, Kohler C, Gur RE, Gur RC. Actively paranoid patients with schizophrenia over attribute anger to neutral faces. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;125:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskulic D, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, Heinssen R, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, McGlashan TH. Negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Psychiatry Research. 2012;196:220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar P, Cooke MA, Fannon D, Peters E, Michel TM, Aasen I, Murray RM, Kuipers E, Kumari V. Misattribution bias of threat-related facial expressions is related to a longer duration of illness and poor executive function in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. European Psychiatry. 2008;23:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rama P, Relander-Syrjanen K, Carlson S, Salonen O, Kujala T. Attention and semantic processing during speech: an fMRI study. Brain Language. 2012;122:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revheim NC, Corcoran CM, Dias E, Hellmann E, Martinez A, Butler PD, Lehfeld JM, DiCostanzo J, Albert J, Javitt DC. Reading deficits in established and prodromal schizophrenia: further evidence for early visual and later auditory dysfunction in the course of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171:949–959. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roalf DR, Gur RE, Ruparel K, Calkins ME, Satterthwaite TD, Bilker WB, Hakonarson H, Harris LJ, Gur RC. Within-individual variability in neurocognitive performance: age- and sex-related differences in children and youths from ages 8 to 21. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:506–518. doi: 10.1037/neu0000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenqvist J, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Laasonen M, Korkman M. Preschoolers’ recognition of emotional expressions: relationships with other neurocognitive capacities. Child Neuropsychology. 2013;20:281–302. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2013.778235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Linszen D, Dingemans P, Birchwood M, Patterson P, Juckel G, Heinz A, Morrison A, Lewis S, von Reventlow HG, Klosterkotter J. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European prediction of psychosis study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruopp MD, Perkins NJ, Whitcomb BW, Schisterman EF. Youden Index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biomedical Journal. 2008;50:419–430. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said CP, Haxby JV, Todorov A. Brain systems for assessing the affective value of faces. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 2011;366:1660–1670. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Meyer EC, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Bearden CE, Christensen BK, Hawkins K, Heaton R, Keefe RS, Heinssen R, Cornblatt BA North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study G. Neuropsychology of the prodrome to psychosis in the NAPLS consortium: relationship to family history and conversion to psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:578–588. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver H, Shlomo N, Turner T, Gur RC. Perception of happy and sad facial expressions in chronic schizophrenia: evidence for two evaluative systems. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;55:171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, MacDonald AW., III Brain mapping biomarkers of socio-emotional processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38:73–80. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Papas A, Bartholomeusz C, Allott K, Amminger GP, Nelson B, Wood S, Yung A. Social cognition in clinical “at risk” for psychosis and first episode psychosis populations. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;141:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valmaggia LR, Stahl D, Yung AR, Nelson B, Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, McGuire PK. Negative psychotic symptoms and impaired role functioning predict transition outcomes in the at-risk mental state: a latent class cluster analysis study. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:2311–2325. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijn S, Aleman A, de Sonneville L, Sprong M, Ziermans T, Schothorst P, van Engeland H, Swaab H. Misattribution of facial expressions of emotion in adolescents at increased risk of psychosis: the role of inhibitory control. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:499–508. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velthorst E, Nieman DH, Becker HE, van de Fliert R, Dingemans PM, Klaassen R, de Haan L, van Amelsvoort T, Linszen DH. Baseline differences in clinical symptomatology between ultra high risk subjects with and without a transition to psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;109:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari S, Reilly JS, Pasqualetti P, Vizzotto A, Caltagirone C. Recognition of facial expressions of emotions in school-age children: the intersection of perceptual and semantic categories. Acta Paediatrica. 2000;89:836–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Administration and Scoring Manual. third. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Wolwer W, Brinkmeyer J, Stroth S, Streit M, Bechdolf A, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, Gaebel W. Neurophysiological correlates of impaired facial affect recognition in individuals at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38:1021–1029. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolwer W, Frommann N. Social-cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: generalization of effects of the Training of Affect Recognition (TAR) Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37(Suppl. 2):S63–S70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeap S, Kelly SP, Sehatpour P, Magno E, Javitt DC, Garavan H, Thakore JH, Foxe JJ. Early visual sensory deficits as endophenotypes for schizophrenia: high-density electrical mapping in clinically unaffected first-degree relatives. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.