Abstract

Background

A need for follow-up recommendations for survivors of fallopian tube, primary peritoneal, or epithelial ovarian cancer after completion of primary treatment was identified by Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care.

Methods

We searched for existing guidelines, conducted a systematic review (medline, embase, and cdsr, January 2010 to March 2015), created draft recommendations, and completed a comprehensive review process. Outcomes included overall survival, quality of life, and patient preferences.

Results

The Cancer Australia guidance document Follow Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer was adapted for the Ontario context. A key randomized controlled trial found that the overall survival rate did not differ between asymptomatic women who received early treatment based on elevated serum cancer antigen 125 (ca125) alone and women who waited for the appearance of clinical symptoms before initiating treatment (hazard ratio: 0.98; 95% confidence interval: 0.80 to 1.20; p = 0.85); in addition, patients in the delayed treatment group reported good global health scores for longer. No randomized studies were found for other types of follow-up. We recommend that survivors be made aware of the potential harms and benefits of surveillance, including a discussion of the limitations of ca125 testing. Women could be offered the option of no formal follow-up or a follow-up schedule that is agreed upon by the woman and her health care provider. Education about the most common symptoms of recurrence should be provided. Alternative models of care such as nurse-led or telephone-based follow-up (or both) could be emerging options.

Conclusions

The recommendations provided in this guidance document have a limited evidence base. Recommendations should be updated as further information becomes available.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, follow-up, surveillance

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, 2700 new cases of ovarian cancer and 1750 deaths from the disease were estimated to have occurred in Canada1. The proportion of people with this cancer who are still alive 5 years after initiation of treatment ranges between 41% and 43%1. Over the past several decades, an improvement in 5-year survival has been observed, likely because of advances in surgical techniques and chemotherapeutic agents2; however, patients with ovarian cancer continue to have a lower rate of survival relative to many other cancer disease sites because diagnosis often occurs at an advanced stage. An estimated 70%–75% of patients will experience a recurrence3, with a median time to recurrence of 18–24 months4.

Structured follow-up of patients who have been classified as disease-free after primary treatment—also known as surveillance—is conducted to identify disease recurrence and to deliver therapeutic interventions that lead to improved outcomes5. Managing the side effects of primary treatment, facilitating recruitment to clinical trials, or building a relationship between the patient and the oncology team in anticipation of a subsequent recurrence have been mentioned as additional reasons for follow-up.

There is some controversy about frequent structured follow-up for patients who are disease-free after treatment for ovarian and other cancers6. Evidence from follow-up of vulvar, cervical, and endometrial cancers has called into question the value of detecting asymptomatic recurrences, and follow-up has even been shown to delay detection, because some women will not report symptoms until their next scheduled appointment7. In the case of cancer in other disease sites (such as the bowel), intensive follow-up does appear to provide a benefit over little or no follow-up8.

The Program in Evidence-Based Care (pebc) is an initiative of the Ontario provincial cancer system, Cancer Care Ontario. The pebc is mandated to improve the lives of Ontarians affected by cancer by developing, disseminating, and evaluating evidence-based products designed to facilitate clinical, planning, and policy decisions about cancer control.

The pebc has published guidelines for follow-up at other gynecologic cancer disease sites, including cervical and endometrial cancers, but there is a gap in recommendations for ovarian cancer. In the experience of the members of the Working Group for the present guideline, many women who have received primary treatment for epithelial ovarian cancer are followed at regular appointments that include history and physical examination in the cancer centre where they received treatment. Methods to detect recurrence—such as testing for serum cancer antigen 125 (ca125), which has been found to predict recurrence several months before physical symptoms are identified; examinations; and imaging tests—can vary from one centre to another, and there is currently no guidance within Ontario about appropriate tests, intervals, or models of follow-up care. To fill that gap in the disease management pathway for patients in Ontario, we created this evidence-based guideline. The intended users are clinicians who provide follow-up examinations to the target population, which can include gynecologic oncologists, medical oncologists, specialist nurses, gynecologists, family physicians, and other clinicians who deliver follow-up cancer care.

METHODS

The pebc uses the methods of the practice guidelines development cycle9 to produce its evidence-based and evidence-informed guidance documents. The process includes a systematic review, interpretation of the evidence, creation of draft recommendations by the members of the Working Group, internal review by content and methodology experts, and external review by clinicians and other stakeholders.

Search for Existing Guidelines

We searched for existing English-language guidelines that were based on a systematic review and that addressed survival rate, quality of life (qol), or level of anxiety associated with various follow-up intervals and methods for detection of recurrence in women with confirmation of remission after surgery and first-line chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer. The search included the National Guidelines Clearinghouse, and the Web sites of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The search yielded the Cancer Australia guideline document Follow Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer10, which closely aligned with the objectives of our project. It was current to January 2010, scored highly on the agree ii11 rigour-of-development domain (Table i), and was based on a systematic review12 that received high amstar quality scores13. The members of the Working Group agreed that the Australian guideline would be suitable for endorsement, potentially with modifications or qualifying statements to suit the Ontario context and pending a search for more recent evidence (systematic reviews and primary studies).

TABLE I.

AGREE II rigour of development scores for the Follow Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer guideline from Cancer Australia10

| Criterion | Scored by … | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Reviewer 1 | Reviewer 2 | |

| Systematic methods were used to search for evidence | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described | 7/7 | 4/7 |

| The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described | 3/7 | 3/7 |

| The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations | 7/7 | 4/7 |

| There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence | 4/7 | 5/7 |

| The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication | 5/7 | 4/7 |

| A procedure for updating the guideline is provided | 2/7 | 4/7 |

Search for Systematic Reviews and Primary Studies

A search of medline, embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for systematic reviews or primary literature that had been published between January 2010 and March 2015 used search terms related to ovarian cancer and to asymptomatic detection of recurrence and follow-up adopted from Cancer Australia’s systematic review12 (Table ii). Systematic reviews found to be directly relevant to the present guideline were assessed using the amstar tool13. The Clinicaltrials.gov database was also searched for in-progress randomized controlled trials (rcts).

TABLE II.

Search strategy (Ovid MEDLINE)

| 1. | (follow up care or |

| follow up plan or | |

| follow up visit or | |

| follow up examination or | |

| clinical follow up or | |

| routine follow up or | |

| follow up model or | |

| follow up strategies or | |

| follow up methods or | |

| follow up program or | |

| routine test or | |

| postoperative surveillance or | |

| ovarian cancer surveillance or | |

| (surveillance and survivors)).mp. | |

| 2. | aftercare/ |

| 3. | postoperative care/ |

| 4. | Ovarian Neoplasms/ |

| 5. | (Ovarian and (cancer or carcinoma or tumour)).mp. |

| 6. | (1 or 2 or 3) and (4 or 5) |

| 7. | limit 6 to yr=“2010 –Current” |

| 8. | limit 33 to English language |

Study Selection Criteria and Process

To limit the review to the highest possible level of evidence, and in view of the fact that our literature search was intended to update an existing source of primary literature, publication types other than rcts were not considered eligible for inclusion. No population size limit was specified for rcts. Studies relating to follow-up of a suspected recurrence are not included in the scope of the present guideline. Articles were limited to those reported in the English language because resources for translation were not available. The titles and abstracts that resulted from the search were reviewed by author EBK.

Synthesizing the Evidence

Given that the members of the Working Group were aware that few studies in this field had been published, a meta-analysis of outcomes was not planned.

Guideline Review

Recommendations were reviewed by an expert panel made up of individuals from Cancer Care Ontario’s Gynecologic Cancer Disease Site Group; the pebc’s Report Approval Panel (a 3-person group with clinical, methodology, and oncology expertise); targeted peer reviewers; and relevant care providers and other potential users of the guideline. The process has previously been described in detail14.

RESULTS

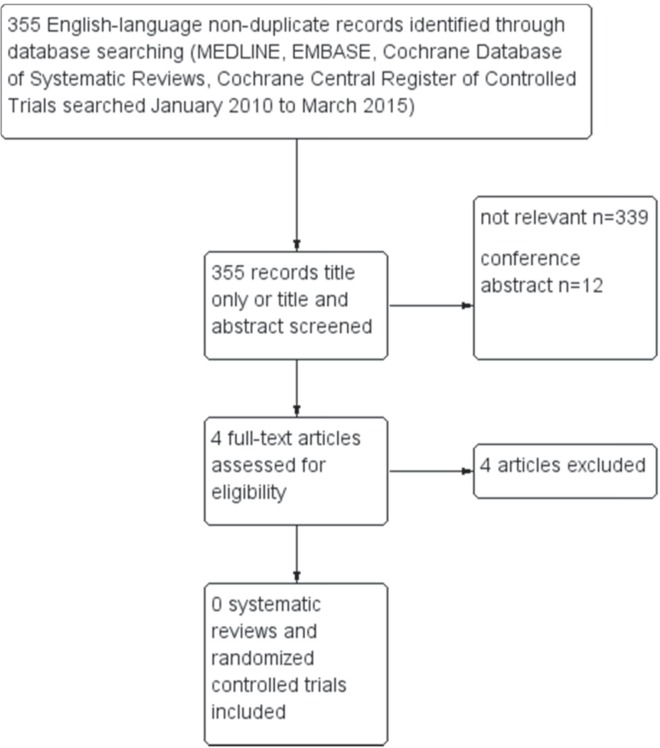

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the search for eligible rcts or systematic reviews published after January 2010. No articles were found that met the inclusion criteria, and the Working Group members therefore agreed to endorse the recommendations from Follow Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer with some consensus-based modifications.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram of search for primary literature and systematic reviews.

Twelve full-text studies constituted the evidence base for the present guideline : one rct of ca125 in follow-up15; five retrospective cohort studies on methods of detection16–20; two pilot studies21,22; and four qualitative or observational studies of psychosocial concerns, health care provider and patient preferences or satisfaction, and patterns of care23–26. Eleven of those studies fell within the scope of our guideline; one study about sexual symptomatology was out-of-scope22. The recommendations from Follow Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer are reproduced in the Recommendations, Key Evidence, and Interpretation of Evidence section, together with their pebc qualifying statements.

Internal Review

Comments were made that the recommendations did not make it clear enough that routine monitoring of ca125 for all patients is not recommended, and conditional approval of the document was given by 2 Report Approval Panel members who questioned the need for any type of routine surveillance, given the lack of evidence for the impact of such surveillance on outcomes. That feedback is addressed in the Discussion section.

External Review

Targeted peer reviewers from Ontario (n = 3), British Columbia (n = 1), and Manitoba (n = 1) reviewed the document. The document received mostly high and some moderate ratings for its development methods, guideline presentation, guideline recommendations, completeness of reporting, and overall quality.

Several comments were made that the guidelines were vague, unclear, or not stringent enough in the requirements for follow up, and could be difficult for a non-oncology specialist to implement. In response, the Working Group emphasized that an individualized treatment plan would be required before transfer of care to a non-specialist clinician and that the recommendations were intentionally written to allow for variability in patient preference about options for frequency and method of follow-up.

Feedback from health care professionals and other stakeholders who are the intended users of the guideline was obtained in a brief online survey. Gynecologic oncologists, family physicians, and advanced-practice nurses with contact information in the pebc database were contacted. Fourteen individual responses were received. Again, the opinion of several practitioners was that the option of no follow-up be given greater prominence. In response, the Working Group changed the wording of the recommendations to indicate that the option of regular follow-up could be offered to women (rather than should be offered) after a discussion of potential harms associated with the practice. When asked about barriers or enablers to implementation of the guideline, practitioners in Ontario felt that there could be some resistance to changing long-standing practice patterns regarding routine testing for ca125, as well as some difficulty in finding sufficient time to discuss with patients the evidence (or lack of evidence) for routine frequent follow-up.

The recommendations, key evidence, and interpretation of the evidence are outlined next, and the recommendations are summarized in Table iii.

TABLE III.

Summary of recommendations

| Domain | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Follow-up after treatment | |

| ■ The optimal method of follow-up has not been established, but possible options and the implications and consequences of those options should be discussed with the woman at the completion of primary treatment. | |

| ■ Consideration should be given to how anxiety might be lessened, such as scheduling tests before the visit so that test results are available for discussion at the time of the follow-up visit. | |

| CA125 in follow-up | |

| ■ A time should be provided for the woman and her clinician to discuss the implications of monitoring progress and initiating treatment based on serum CA125. Women who choose to have serum CA125 measured should be informed that there is no evidence that monitoring CA125 improves survival outcomes, that monitoring could worsen quality of life15, and that CA125 can fluctuate because of individual and laboratory assay variations. The implications of a stable, fluctuating, and rising level should be discussed. | |

| Timing of follow-up consultations | |

| ■ Discussion with the woman about follow-up could incorporate a schedule of follow-up appointments, including the possibility of no formal follow-up schedule, based on the identified needs and wishes of the individual. | |

| ■ There is no recommended frequency of follow-up consultations, but a clear and mutually agreed arrangement should be negotiated with the woman, tailored according to risk and to individual patient characteristics, thus acknowledging the benefits of an ongoing relationship and the opportunity to deal with issues as they arise. | |

| ■ Women residing in rural and regional areas face additional challenges of access to specialist clinicians for follow-up appointments. Individual circumstances should be considered when establishing a follow-up schedule. | |

| Format for follow-up consultations | |

| ■ The basic format of consultation is to update the patient history, assess psychosocial and supportive care needs, and undertake physical examination, which can include pelvic examination. | |

| ■ Women should be encouraged to report a range of symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, cramping, pain, shortness of breath, and any other concerning symptom. | |

| ■ Radiologic imaging should not routinely be done, but should be performed in the presence of clinical or CA125 evidence of recurrence. The rationale for not undertaking routine imaging should be discussed with the woman. | |

| Models of follow-up care | |

| ■ A woman can be reviewed by either a gynecologic oncologist or a medical oncologist. Communication with a woman’s primary care physician should be maintained throughout follow-up. | |

| ■ The use of alternative models of care for women with ovarian cancer, such as follow-up led by the primary care physician or nurse, telephone follow-up, and patient-initiated care is an area for future research. Some of the issues that would have to be addressed in any future studies include patient and clinician preferences, the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the alternative models, and the ability of health services to support the models. | |

RECOMMENDATIONS, KEY EVIDENCE, AND INTERPRETATION OF THE EVIDENCE

Recommendations for Follow-Up After Treatment

■ Although the optimal method of follow-up has not been established, possible options for follow-up, and the implications and consequences of those options, should be discussed with the woman at completion of primary treatment.

■ Consideration should be given to how anxiety might be lessened—for example, scheduling tests before a visit so that test results are available for discussion at the time of the follow-up visit.

PEBC Qualifying Statement

Based on feedback received in the pebc review process, the members of the Working Group for this guideline would like to emphasize that women should clearly be given the option of no follow-up, because there is no evidence for any impact of routine follow-up on outcomes, and because follow-up appointments can be associated with stress, inconvenience, and cost. A further recommendation is to provide survivors with written information, potentially in the form of a fact sheet, outlining symptoms of concern (as described under the Recommendations for Format of Follow-up Consultations), follow-up suggestions, and when and how to contact the appropriate specialist.

Recommendations for CA125 in Follow-Up

■ Time should be provided for the woman and her clinician to discuss the implications of monitoring progress and initiating treatment based on serum ca125. Women who choose to have serum ca125 measured should be informed that there is no evidence that monitoring ca125 improves survival outcomes, that such monitoring might worsen quality of life15, and that serum ca125 can fluctuate because of individual and laboratory assay variation. The implications of stable, fluctuating, and rising levels should be discussed.

PEBC Qualifying Statement

Treatment based on rising serum ca125 alone is not recommended. Clinical or radiologic confirmation of disease progression should be obtained before re-initiation of treatment.

PEBC Qualifying Statement

Based on feedback from the review process for this guideline, the members of the Working Group have chosen to emphasize the limitations and potential harms of routine measurement of serum ca125.

Key Evidence for CA125 in Follow-Up

The hazard ratio for the overall survival rate did not differ between asymptomatic women who received early treatment based on elevated serum ca125 alone and women who waited for the appearance of clinical symptoms before initiating treatment (hazard ratio: 0.98; 95% confidence interval: 0.80 to 1.20; p = 0.85)15.

Quality-of-life results showed that good global health scores were reported for longer by patients in the delayed treatment group than by those in the early treatment arm [9.2 months (95% confidence interval: 6.4 to 10.5 months) vs. 7.2 months (95% confidence interval: 5.3 to 9.3 months)]15.

Recommendation for Timing of Follow-Up Consultations

■ Discussion with the woman about follow-up could incorporate a schedule of follow-up appointments, including the possibility of no formal follow-up schedule, based on the identified needs and wishes of the individual.

■ There is no recommended frequency for follow-up consultations; however, a clear and mutually agreed arrangement should be negotiated with the woman, tailored according to risk and individual patient characteristics, and acknowledging the benefits of an ongoing relationship and the opportunity to deal with issues as they arise.

■ Women residing in rural and regional areas face additional challenges of access to specialist clinicians for follow-up appointments. Individual circumstances should be considered when establishing a follow-up schedule.

PEBC Qualifying Statement

No specific frequency of follow-up appointments is endorsed; however, if desired, follow-up visits could occur more frequently immediately after completion of active treatment, and might occur less frequently after more time has passed since the completion of active treatment.

Recommendations for Format of Follow-Up Consultations

■ The basic format of the consultation is to update patient history, assess psychosocial and supportive care needs, and undertake physical examination, which might include pelvic examination.

■ Women should be encouraged to report a range of symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, cramping, pain and shortness of breath, and any other concerning symptoms.

■ Radiologic imaging should not be routine, but should be performed if there is clinical or ca125 evidence of recurrence. The rationale for not undertaking routine imaging should be discussed with the woman.

PEBC Qualifying Statement

Patients should be informed that physical examination has a low level of sensitivity for detecting early recurrence of cancer, particularly if the patient is also undergoing regular monitoring for ca125.

PEBC Qualifying Statement

In the case of transfer of care from the patient’s oncologist to a clinician such as a gynecologist, family physician, or nurse practitioner, a written, individualized plan should be developed by the oncologist in consultation with the patient for provision to the clinician to whom care is being transferred. That document should include plans for patient care in the event of delayed or long-term treatment sequelae.

Key Evidence: Methods of Detection

Chan et al.16 found that women with abnormal findings on physical examination also had either suspicious symptoms, elevated serum ca125, or both. No patient presented with physical findings alone.

Signs and symptoms of recurrent ovarian cancer are based on the findings of Chan et al.16.

The recommendation for radiologic imaging to detect recurrence is based on evidence from Fehm et al.17. Their study found that imaging techniques did not add clinically relevant information during follow-up and should therefore be performed only before a planned surgical or therapeutic intervention17.

Recommendation for Models of Follow-Up Care

■ A woman could be reviewed by either a gynecologic oncologist or a medical oncologist. Communication with a woman’s primary care physician should be maintained throughout follow-up.

■ The use of alternative models of care for women with ovarian cancer, such as primary care physician–led or nurse-led follow-up, telephone follow-up, and patient-initiated care is an area for future research. Some of the issues that would have to be addressed in any future studies include patient and clinician preferences, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the alternative models, and the ability of health services to support them.

Key Evidence: Models of Follow-Up Care

A previous guideline by the pebc recommended discharge from specialist care to community-based family physician–led care or nurse-led care within an institution as a reasonable option for breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer patients27. At the time of that report, evidence for other disease sites was not available.

A pilot study21 of ovarian cancer patients agreeing to participate in a telephone follow-up study found that 73% of women preferred telephone follow-up, 18% preferred doctor or consultant appointments, and 9% were “not sure”.

Ovarian cancer patients who agreed to participate in the pilot trial of nurse-led follow-up reported significant improvements in post-treatment well-being with nurse-led telephone follow-up (p = 0.016)21.

Further Qualifying Statements

The Working Group members emphasize that, if women opt not to engage in routine follow-up, they must be fully informed about signs and symptoms of recurrence and be instructed to contact their oncologist or primary care provider if signs and symptoms suggestive of recurrence appear.

DISCUSSION

Follow-Up Methods

Serum ca125 can accurately predict recurrence approximately 4.5 months before symptoms become apparent28; however, the only rct to compare early with delayed chemotherapy for treatment of recurrence found that early treatment based on elevated serum ca125 did not translate into a survival rate advantage and had a potential detrimental effect on qol15. Despite those findings, the European Society for Medical Oncology recommends that clinicians can continue to conduct follow-up with serum ca12529; and, while agreeing that routine use of serum ca125 does not provide patient benefit in terms of survival rate or qol, the society recommends its use for epithelial ovarian cancer survivors who currently are or who will be participating in a study, who will not have frequent (every 3 months) follow-up, or for whom secondary surgery will be considered upon recurrence.

This issue of ca125 testing will be better understood when the results of desktop iii are published. The desktop iii rct is comparing debulking surgery plus chemotherapy with chemotherapy alone for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer; it recruited patients up to August 201530. A previous desktop study (desktop ii31) found that, with an experienced surgeon, complete resection is possible at first relapse (predicted by an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 at relapse, complete resection at the original surgery, and no ascites at relapse). Earlier detection by ca125 testing might increase the likelihood that patients meet the criteria and thus become candidates for debulking5. The feeling of some clinicians is that, if ca125 monitoring is curtailed, then reintroduction, should it prove to be of value, could be confusing and difficult—that is, if the results of desktop iii confirm the value of surgery plus chemotherapy at recurrence29.

Regarding other methods of detection, physical examination has low sensitivity16,28,32, and ultrasonography has not been shown to be more useful than a combination of ca125 testing and clinical examination8. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have a role in treatment planning when a recurrence has been diagnosed; the roles of positron-emission tomography and Doppler ultrasonography are currently unclear8.

In spite of the sparse evidence base underpinning the recommendations for follow-up, it is the consensus of the members of the Working Group that the benefits of surveillance might outweigh the harms for some women in this patient population, and thus, the option of regular follow-up could be offered to that patient population, conditional on a discussion of the potential for harm. In the Working Group’s opinion, the greatest potential benefit of ongoing follow-up—given the high likelihood of recurrence—is maintenance of a relationship with the oncologist and the reassurance associated with continued involvement in the cancer care system. A study found that 45% of patients with cancer cite the emotional effects of cancer as the most difficult to cope with21, and unmet psychological needs could be more prevalent than unmet physical needs in this patient population33. A possible benefit of follow-up is the potential opportunity to identify women who might need referral for counselling for psychological needs or for social support services21. Other potential benefits include prompt identification of women who could be candidates for open clinical trials and the opportunity to discuss the importance of genetic testing and familial counselling. In addition, some patients may view appointments as reassuring25.

The Working Group members identified several harms that are associated with routine surveillance, including a potentially shorter time living in a progression-free status, with no corresponding increase in overall survival duration, and a decrease in qol because of earlier initiation of treatment, anxiety associated with follow-up, inconvenience and cost of attending follow-up appointments, and potential for unnecessary and costly follow-up testing in the case of falsely elevated serum ca125. Testing for ca125 has been associated with depression and anxiety in early-stage ovarian cancer33. Fear of recurrence, defined as “fear that the cancer will return or progress in the same place or a different part of the body”3, is one of the greatest concerns expressed by survivors. It is possible that frequent follow-up testing for ovarian cancer can elevate fear of recurrence34. Of respondents in the pilot study reported by Cox et al.21, 33% discussed fear of recurrence with the nurse during telephone-based follow-up. That study was associated with improvements in emotional well-being among patients.

A further potential harm of frequent follow-up is the deterioration in qol that can potentially occur with earlier initiation of treatment when asymptomatic disease is detected by ca125 testing at routine follow-up appointments15. In addition, there is some evidence showing that patients might delay reporting of symptoms until a routine scheduled follow-up appointment, which could possibly result in a delay in the diagnosis of recurrent disease7. Finally, there is some disagreement about whether management of residual side effects should be a goal of follow-up5,35, because such effects can resolve independently over time5.

Follow-Up Schedule

No published studies have compared one follow-up schedule with another. Several guidelines recommend a frequent schedule of follow-up. For example, the European Society for Medical Oncology29 recommends history and physical examination, including pelvic examination, every 3 months for 2 years, every 4 months during the 3rd year, and every 6 months during years 4 and 5, or until progression is documented.

Models of Follow-Up Care

Delivery of follow-up by providers other than the primary treating specialists might be feasible, provided that prompt access to specialized services is available. A previous guideline published by the pebc recommended discharge from specialist care to community-based family physician–led care or nurse-led care within an institution as a reasonable option for patients with breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer27. Further recommendations specific to gynecologic oncology patients or to other models of care such as shared care or nurse-led care in a community setting could not be made in that guideline because of a lack of published evidence27. Since then, the nurse-led telephone-based intervention study mentioned earlier was published; its results show that its method of follow-up is likely to be feasible in the ovarian cancer survivor population. The high satisfaction ratings given by the patients in that study suggest that nurses are well-equipped to address the psychosocial concerns of patients, which are among the highest needs of ovarian cancer patients, and that this type of follow-up could be an area for further research. The pebc is also awaiting the findings of a British rct investigating a similar model of care (http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN59149551), which has been completed but not yet reported.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the lack of evidence for any particular follow-up schedule or method of recurrence detection, follow-up for ovarian cancer requires a critical appraisal5. Survivors should be made fully aware of the potential harms and benefits of surveillance, including a thorough discussion of the limitations of ca125 testing. Women could be offered the option of no formal follow-up or a follow-up schedule on which the woman and the health care provider have mutually agreed. Regardless of the follow-up schedule adopted, women should be educated about the most common symptoms of recurrence, which include abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort or distension, nausea or vomiting, and shortness of breath16, with abdominal pain being the most commonly reported symptom10. They should also be provided with clear information about how to contact appropriate health care professionals when and if potential symptoms are detected. A further recommendation is to provide survivors of ovarian cancer with written information, potentially in the form of a fact sheet outlining symptoms of concern, follow-up suggestions, and when and how to contact the appropriate specialist.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The pebc’s Gynecologic Cancer Disease Site Group thanks the following individuals for providing feedback on draft versions of this guideline: Alon Altman, Melissa Brouwers, Craig Earle, Paul Hoskins, Monique Lefebvre, Jake McGee, Sheila McNair, Hans Messersmith, Fulvia Baldassarre, Raymond Poon, and Rebecca Wong. Crystal Su are also thanked for conducting a data audit.

The pebc is a provincial initiative of Cancer Care Ontario, supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (mohltc). All work produced by the pebc is editorially independent from the mohltc.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2015. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantia-Smaldone G, Edwards R, Vlad A. Targeted treatment of recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: current and emerging therapies. Cancer Manag Res. 2010;3:25–38. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozga M, Aghajanian C, Myers-Virtue S, et al. A systematic review of ovarian cancer and fear of recurrence. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:1771–80. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ushijima K. Treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer-at first relapse. J Oncol. 2010;2010:497429. doi: 10.1155/2010/497429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoskins P. Follow-up of epithelial ovarian cancer: overdue for a major rethink. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:204–6. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0310-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brada M. Is there a need to follow-up cancer patients? Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:655–7. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00079-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olaitan A, Murdoch J, Anderson R, James J, Graham J, Barley V. A critical evaluation of current protocols for the follow-up of women treated for gynecological malignancies: a pilot study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:349–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke T, Galaal K, Bryant A, Naik R. Evaluation of follow-up strategies for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer following completion of primary treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD006119. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006119.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browman GP, Levine MN, Mohide EA, et al. The practice guidelines development cycle: a conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:502–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Australia . Follow Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Surry Hills, Australia: Cancer Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. on behalf of the agree Next Steps Consortium agree ii: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (nbocc) Follow-Up of Women with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review. Surry Hills, Australia: NBOCC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of amstar: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung-Kee-Fung M, Kennedy EB, Biagi J, et al. An organizational guideline for gynecologic oncology services. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:551–8. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rustin GJ, van der Burg ME, Griffin CL, et al. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer (mrc OV05/eortc 55955): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1155–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan KK, Tam KF, Tse KY, Ngan HY. The role of regular physical examination in the detection of ovarian cancer recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:158–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehm T, Heller F, Kramer S, Jager W, Gebauer G. Evaluation of ca125, physical and radiological findings in follow-up of ovarian cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1551–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gadducci A, Fuso L, Cosio S, et al. Are surveillance procedures of clinical benefit for patients treated for ovarian cancer?: A retrospective Italian multicentric study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:367–74. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a1cc02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Velloso MJ, Jurado M, Ceamanos C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fdg pet in the follow-up of platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1396–405. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Georgi R, Schubert K, Grant P, Munstedt K. Post-therapy surveillance and after-care in ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114:228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox A, Bull E, Cockle-Hearne J, Knibb W, Potter C, Faithfull S. Nurse led telephone follow up in ovarian cancer: a psychosocial perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:412–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amsterdam A, Krychman ML. Sexual dysfunction in patients with gynecologic neoplasms: a retrospective pilot study. J Sex Med. 2006;3:646–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kew FM, Cruickshank DJ. Routine follow-up after treatment for a gynecological cancer: a survey of practice. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:380–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kew FM, Galaal K, Manderville H, Verleye L. Professionals’ and patients’ views of routine follow-up: a questionnaire survey. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:557–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lydon A, Beaver K, Newbery C, Wray J. Routine follow-up after treatment for ovarian cancer in the United Kingdom (UK): patient and health professional views. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:336–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer C, Pratt J, Basu B, Earl H. A study to evaluate the use of ca125 in ovarian cancer follow-up: a change in practice led by patient preference. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sussman J, Souter LH, Grunfeld E, et al. Models of Care for Cancer Survivorship. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rustin GJ. What surveillance plan should be advised for patients in remission after completion of first-line therapy for advanced ovarian cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(suppl 2):S27–8. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181f63a28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verheijen RH, Cibula D, Zola P, Reed N, on behalf of the Council of the European Society of Gynaecologic Oncology Cancer antigen 125: lost to follow-up?: a European Society of Gynaecological Oncology consensus statement. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:170–4. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318226c636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer Research UK . A trial looking at surgery for ovarian cancer that has come back (desktop 3) [Web page] London, UK: Cancer Research UK; 2015. [Available at: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/trials/a-trial-looking-surgery-ovarian-cancer-that-come-back-desktop-3; cited 11 May 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harter P, Sehouli J, Reuss A, et al. Prospective validation study of a predictive score for operability of recurrent ovarian cancer: the Multicenter Intergroup Study desktop ii. A project of the ago Kommission ovar, ago Study Group, noggo, ago-Austria, and mito. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289–95. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31820aaafd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menczer J, Chetrit A, Sadetzki S, Golan A, Levy T. Follow-up of ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma: the value of physical examination in patients with pretreatment elevated ca125 levels. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:137–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matulonis UA, Kornblith A, Lee H, et al. Long-term adjustment of early-stage ovarian cancer survivors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1183–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donovan KA, Donovan HS, Cella D, et al. Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms and quality-of-life domains to measure in ovarian cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju128. pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.United Kingdom Department of Health National Health Service . Guidance on Commissioning Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes in Gynaecological Cancers – The Manual. Wetherby, U.K.: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]