Abstract

Aims

Normalization of hypercholesterolaemia, inflammation, hyperglycaemia, and obesity are main desired targets to prevent cardiovascular clinical events. Here we present a novel regulator of cholesterol metabolism, which simultaneously impacts on glucose intolerance and inflammation.

Methods and results

Mice deficient for oxygen sensor HIF-prolyl hydroxylase 1 (PHD1) were backcrossed onto an atherogenic low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) knockout background and atherosclerosis was studied upon 8 weeks of western-type diet. PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice presented a sharp reduction in VLDL and LDL plasma cholesterol levels. In line, atherosclerotic plaque development, as measured by plaque area, necrotic core expansion and plaque stage was hampered in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice. Mechanistically, cholesterol-lowering in PHD1 deficient mice was a result of enhanced cholesterol excretion from blood to intestines and ultimately faeces. Additionally, flow cytometry of whole blood of these mice revealed significantly reduced counts of leucocytes and particularly of Ly6Chigh pro-inflammatory monocytes. In addition, when studying PHD1−/− in diet-induced obesity (14 weeks high-fat diet) mice were less glucose intolerant when compared with WT littermate controls.

Conclusion

Overall, PHD1 knockout mice display a metabolic phenotype that generally is deemed protective for cardiovascular disease. Future studies should focus on the efficacy, safety, and gender-specific effects of PHD1 inhibition in humans, and unravel the molecular actors responsible for PHD1-driven, likely intestinal, and regulation of cholesterol metabolism.

Keywords: Oxygen sensor, Cholesterol and lipids, Hyperglycaemia, Atherosclerosis, Inflammation

Cardiovascular risk management aims to lower hypertension, LDL-C, inflammation and hyperglycaemia.1 Statins are moderately effective in lowering cholesterol and cardiovascular risk, but only fewer than 1 in 3 adults in the USA with elevated LDL-C achieve desired LDL-C lowering with statins, and only 30–40% of recurrent events is prevented.2 As a more effective alternative, anti-inflammatory agents are currently evaluated in clinical trials, but results are still unknown. As atherosclerotic plaque hypoxia co-localizes with inflammation in humans and mice, and inflammation is thought to give rise to hypoxia, we aim to interfere with hypoxic signalling in atherosclerotic plaques.

Here, we present a novel universal player in cardiovascular risk management, namely the oxygen sensor HIF-prolyl hydroxylase 1 (PHD1). The three PHD isoforms are best known for their function in hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIFα) regulation. In normoxia, PHDs hydroxylate HIF1α and 2α targeting it for von Hippel–Lindau protein-mediated proteasomal degradation. In hypoxia, however, HIFα is stabilized, starting HIF-mediated transcription for cellular adjustment to hypoxia. This results in, amongst others, limited oxygen demand, restored oxygen supply, and prevention of excessive cell death.3,4 More specifically, PHD1 deficiency has recently been shown to re-programme cellular metabolism to glycolysis and thus lower oxygen consumption in an HIF2α-dependent way.5 HIFα-independent functions have also been described for PHD1, including cell cycle progression regulation.6 Our original hypothesis was to restore plaque normoxia and study the role of plaque hypoxia in atherogenesis. Indeed, PHD1 deficiency reduced atherosclerotic plaque hypoxia without changes in macrophage density (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1A). Unexpectedly, however, we uncovered a novel link between the oxygen sensor PHD1 and cholesterol homeostasis, as PHD1 deficiency reduced LDL-C levels, circulating immune cell numbers, atherogenesis, and glucose intolerance.

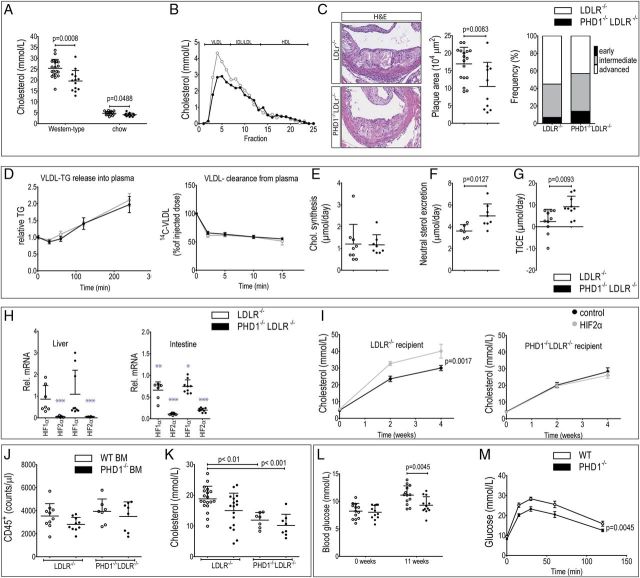

Mice double deficient for PHD1 (Chromosome 7—NC_000073.6; targeted deletion exons 2, 3) and the LDL receptor (PHD1−/−LDLR−/−) were fed a western-type diet (0.25% cholesterol) to induce hypercholesterolaemia and atherogenesis. Plasma cholesterol in LDLR−/− mice is mainly carried in IDL/LDL particles, thus resembling a lipid profile in dyslipidaemic humans.7 In this model of dyslipidaemia, PHD1−/−LDLR−/−showed reduced total, and VLDL and LDL contained plasma cholesterol compared with littermate controls (Figure 1A and B, see Supplementary material online, Figure S1B and C). Importantly, PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice also developed much smaller atherosclerotic plaques, with reduced necrotic core and less advanced plaque stages (Figure 1C, n=17 LDLR−/−, n=10 PHD1−/−LDLR−/−). Interestingly, PHD1 mRNA and immunoreactivity expression in human atherosclerotic plaques did not correlate with plaque phenotype (intraplaque haemorrhage, lipid core, necrotic core T cells, or CD31-positive vessels) (see Supplementary material online, Table S1 and Figure S2), suggesting systemic, rather than plaque-derived PHD1 as regulator of cholesterol levels. Mechanistically, the cholesterol lowering was neither due to hepatic VLDL-triglycerides (TG) release nor did it reflect hepatic VLDL clearance, as studied using dual-labelled VLDL-like particles (Figure 1D; Hepatic VLDL-TG production was assessed in two independent studies PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice compared with controls (n=10/genotype per study) using two different lipoprotein lipase (LPL) inhibitors, Poloxamer 407 and Triton WR1339, respectively. Mice were fasted for 4 h and then injected with the LPL inhibitor. This inhibits peripheral TG clearance, thus TG measured in the plasma over time reflects VLDL-TG release from the liver. To assess VLDL clearance, we generated glycerol tri[3H]oleate and [14C]cholesteryl oleate ([3H]TO, [14C]CO) double-labelled VLDL-like particles, allowing tracing of the selective clearance of triglycerides via LPL-mediated delipidation by tracing [3H]TO, in addition to clearance of cholesteryl-ester-containing remnant particles ([14C]CO)). Finally, cholesterol synthesis was not changed in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice (Figure 1E). Also, intestinal gene expression and morphology suggested preserved barrier function and viability (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1D). Whole body cholesterol flux tracing, however, revealed elevated cholesterol excretion by direct trans-intestinal cholesterol excretion (TICE) directly from the plasma, with subsequent flux to the faeces in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice, to underlie cholesterol lowering (Figure 1F and G; whole body cholesterol flux was measured using stable isotope labelling of cholesterol in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice and controls (n = 10/genotype) after 8 weeks on western-type diet. Cholesterol-D7 and -D5 were administered orally or IV, respectively, and cholesterol was traced in plasma and faeces over time. Additionally, endpoint bile production and bile composition was assessed. Based on these parameters, cholesterol flux can be calculated17). Thus, PHD1 deficiency likely affects cholesterol homeostasis in a different manner than statins or PSCK9 inhibitors.

Figure 1.

(A) Total plasma cholesterol levels in LDLR−/− (n=20) and PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice (n=13) on western-type diet and on normal chow (n=20 per genotype). (B) Lipoprotein fractioning of plasma pools of n=13 PHD1−/−LDLR−/− and n=20 LDLR−/− mice on western-type diet. (C) Representative pictures and quantification of atherosclerotic plaque area, necrotic core and plaque stage frequency per genotype in n=17 LDLR−/− and n=13 PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice. (D) VLDL-TG release from liver and VLDL-cholesteryl-ester clearance from plasma over time (n=10 per genotype). (E) Cholesterol synthesis upon 13-C acetate administration in drinking water (separate study, n=10 per genotype). (F) Neutral sterol excretion measured in faeces of PHD1−/−LDLR−/− (n=8) and control mice (n=6). (G) Trans-intestinal cholesterol excretion assessed upon whole body cholesterol flux analysis in n=10 mice per genotype. Messenger RNA knockdown efficiency in liver and intestines of LDLR−/− (n = 16 ctrl ASO, n = 7 HIF-2α ASO) and PHD1−/−LDLR−/− (n = 9 ctrl ASO, n = 10 HIF-2α ASO) mice receiving control or HIF2α targeting ASO combined with Western-type diet twice weekly. Data is presented relative to HIF1α and HIF2α expression respectively in LDLR−/− mice receiving control ASO injections (***p < 0.0001, **p = 0.0013, *p = 0.0394). J Plasma cholesterol levels after ASO treatment. Homogeneity of variances was first tested and confirmed using Levene's (IBM SPSS statistics 22). Subsequently, variables were analysed using repeated measured (mixed model) ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post-test. (J) Blood leukocyte count and (K) plasma cholesterol levels upon PHD1−/− or WT bone marrow transplantation into LDLR−/− (n=17/19, respectively) or PHD1−/−LDLR−/− recipient mice (n=8/7, respectively), analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. (L) Fasting blood glucose levels and (M) glucose tolerance test in PHD1−/− and WT controls (n=13 per genotype). For the glucose tolerance test, area under the curve was calculated with subsequent normal distribution testing using Shapiro–Wilk, followed by the Student's t-test.

At the molecular level, PHD enzymes 1–3 have different affinity for the HIFα subunits, with PHD1 inhibition mainly resulting in HIF2α stabilization.3 Unexpectedly, HIF2α stabilization could not explain the phenotype observed, as antisense oligonucleotide (ASO)-mediated HIF2α silencing in liver and intestines (80–90% knockdown efficiency) did not alter plasma cholesterol levels in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice, while it elevated cholesterol in control mice (Figure 1H and I; ASOs were injected twice weekly intraperitoneally (25 mg/kg). Western-type diet was initiated simultaneously with first ASO injections).

Besides normalization of hypercholesterolaemia, PHD1 deficiency also reduced leucocyte counts in blood. Although this reduction was seen across all leucocyte subsets investigated, the effect was most pronounced for natural killer (NK), NK-T cells, and Ly6Chigh monocytes in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice (Table 1), both implicated in atherosclerosis.8 Of particular importance for plaque development, the ratio of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Clow monocytes was substantially reduced in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice (Table 1), potentially partly explaining atheroprotection upon PHD1 deficiency. A similar trend was observed for PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice on normal chow diet compared with their littermate controls, while myeloid progenitors in bone marrow did not show aberrant leucocyte differentiation (see Supplementary material online, Table S2).

Table 1.

Blood leukocyte patterns in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice and controls on a western-type diet (n=10 per genotype)

| Blood parameter | LDLR−/− (mean ± D) | PHD1−/−LDLR−/− (mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD45+ leucocytes (counts/µL)a | 2954 ± 829.9 | 1792 ± 627.1 | 0.0014* |

| CD3+ T cells (counts/µL)a | 283.5 ± 69.17 | 213.7 ± 73.93 | 0.0553 |

| CD4+ T cells (counts/µL)a | 162.3 ± 43.91 | 124.6 ± 40.90 | 0.1088 |

| CD8a+ T cells (counts/µL)a | 106.4 ± 22.81 | 78.06 ± 29.77 | 0.033* |

| NK-T cells (counts/µL)a | 34.33 ± 16.43 | 11.91 ± 9.144 | 0.0012* |

| NK cells (counts/µL)a | 98.66 ± 24.28 | 46.15 ± 13.12 | 0.0001* |

| B220+ B cells (counts/µL)a | 749.6 ± 279.8 | 522.1 ± 261.5 | 0.0702 |

| Ly6Chigh monocytes (counts/µL)a | 180.5 ± 104.2 | 68.23 ± 67.18 | 0.025* |

| Ly6Cint monocytes (counts/µL)a | 17.37 ± 5.370 | 10.17 ± 6.826 | 0.0418* |

| Ly6Clow monocytes (counts/µL)a | 65.89 ± 16.51 | 55.21 ± 29.18 | 0.1416 |

| Ly6Chigh/Ly6Clow ratioa | 2.48 ± 1.166 | 1.067 ± 0.7174 | 0.0164* |

| Red Blood cells (·1012/L)a | 9.036 ± 1.097 | 8.610 ± 1.404 | 0.1027 |

| Haematocrit (L/L) | 0.4149 ± 0.03968 | 0.4418 ± 0.03707 | 0.1104 |

| Haemoglobin (mmol/L)a | 8.400 ± 0.8230 | 8.844 ± 0.8110 | 0.1326 |

| Platelets (·109/L)a | 823.1 ± 69.29 | 817.8 ± 239.7 | 0.937 |

All data were tested for normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Variables indicated with the letter ‘a’ did not pass normality test and were subsequently analysed using Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. All other variables were tested with the Student's t-test. * indicates p-value <0.05.

Intriguingly, transplantation of PHD1−/− bone marrow into LDLR−/− or PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice did not affect inflammatory cell counts (Figure 1J). Plasma cholesterol levels, in turn, were again reduced by stromal PHD1 knockout compared with minor changes in cholesterol upon haematopoietic PHD1 deficiency (Figure 1K). Although this suggests a cholesterol-independent effect of PHD1 on leucocyte count, irradiation effects on inflammation cannot be excluded.9 Overall, general PHD1 deficiency reduced leucocyte counts, whether this is secondary to cholesterol-lowering remains to be established.

In addition to beneficial cholesterol- and Ly6Chigh-lowering effects, the potential of PHD1 deficiency to improve glucose intolerance in response to diet-induced obesity was investigated, as PHD1 deficiency enhanced glycolysis.5 Indeed, PHD1−/− mice were protected against high-fat diet-induced hyperglycaemia and glucose intolerance (Figure 1L and M; After 11 weeks of high-fat diet, PHD1−/−, and WT controls (n=13/genotype) were fasted for 6 h and subsequently injected with 1 g/kg glucose intraperitoneally. Plasma glucose levels were traced over time in blood (0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after initial injection)).

The relevance of these findings for human cardiovascular disease is shown by PHD2-selective inhibitors Roxadustat and GSK1278863 mirroring the cholesterol-lowering seen in PHD1−/−LDLR−/− mice.10,11 Also, murine PHD2 hypomorphism lowers plasma cholesterol levels on chow.12 Yet, these compounds and PHD2 hypomorphism additionally lower HDL, and effects on atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events remain uninvestigated. The mentioned PHD inhibitors are currently advancing to phase 3 clinical trials as erythropoietin-stimulating agents to alleviate anemia.13 However, erythropoiesis was fully untouched by PHD1 deficiency (Table 1). Thus at least for PHD1 deficiency, the mechanism of cholesterol lowering is independent of erythropoietic effects and HDL was unchanged (Figure 1B). This is of particular importance for patients with heightened cardiovascular risk as raising erythropoiesis and elevated haematocrit is known to enhanced the risk of thrombotic events.14–16

Overall, we show that oxygen sensor PHD1 deficiency lowers plasma cholesterol levels independent of erythropoiesis and HIF2α, by stimulation TICE in male mice. Additionally, PHD1 deficiency improves glucose tolerance in diet-induced obesity in male mice. Future studies should focus on the efficacy, safety, and gender-specific effects of PHD1 inhibition in humans and unravel the molecular mechanism of PHD1-driven, likely intestinal, regulation of cholesterol metabolism.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Authors' contributions

T.H.v.D., E.M., M.R.B., P.C.N.R., A.K.G., J.C.S., J.A.F.D. performed statistical analysis; J.C.S., M.J.A.P.D. handled funding and supervision; E.M., J.A.F.D., T.L.T., B.M.E.T., M.R.B., K.W., M.J., T.H.v.D., L.J.D., S.J.R.M., M.M. acquired the data; E.M., E.A.F, M.J.A.P.D., P.C.N.R., P.C., A.K.G., J.C.S. conceived and designed the research; E.M., J.C.S., E.A.L.B. drafted the manuscript; P.C., E.A.L.B., M.J.A.P.D., M.R.B., P.C.N.R., A.K.G., T.H.v.D., E.A.F., J.C.S., E.M., L.J.D., K.W. made critical revision of the manuscript for key intellectual content.

Funding

This work was supported by the Cardiovascular Research Institute (CARIM PhD fellowship to T.L.T.), the Netherlands Scientific Organization (NWO VENI, to J.C.S.); the Dutch Heart Foundation (NHS2009T038 to P.C.N.R.); “the Netherlands CardioVascular Research Initiative” (CVON, funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation, Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research, and Development and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences, CVON2011-19 to P.C.N.R.); by the Belgian Science Policy (IAP P7/03 to P.C.); long-term Methusalem funding by the Flemish Government (to P.C.), and grants from the FWO—Flemish Government (G.0595.12.N, G.0671.12N to P.C.), and the National Institutes of Health (HL127930 to E.A.F.).

Conflict of interest: Relationships to industry do not exist for E.M., J.A.F.D., T.L.T., B.M.E.T., K.W., M.R.B., T.H.v.D., M.J.G., L.J.D., E.A.F., E.B., M.J.A.P.D., P.C., S.J.R.M., M.M., A.K.G., and J.C.S. P.C.N.R. received research funding from MSD (unrelated to this work). G.H. is employed by ISIS Pharmaceuticals, supplying the ASOs used in this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. NIH. Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents – NHLBI, NIH [Internet]. Report. 2012. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/current/cardiovascular-health-pediatric-guidelines (16 January 2016).

- 2. CDC. National Health Report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors—United States, 2005–2013. 2014;63:3–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Appelhoff RJ, Tian Y-M, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. 2004;279:38458–38465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. 2001;107:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aragonés J, Schneider M, Van Geyte K, Fraisl P, Dresselaers T, Mazzone M, Dirkx R, Zacchigna S, Lemieux H, Jeoung NH, Lambrechts D, Bishop T, Lafuste P, Diez-Juan A, Harten SK, Van Noten P, De Bock K, Willam C, Tjwa M, Grosfeld A, Navet R, Moons L, Vandendriessche T, Deroose C, Wijeyekoon B, Nuyts J, Jordan B, Silasi-Mansat R, Lupu F, Dewerchin M, Pugh C, Salmon P, Mortelmans L, Gallez B, Gorus F, Buyse J, Sluse F, Harris RA, Gnaiger E, Hespel P, Van Hecke P, Schuit F, Van Veldhoven P, Ratcliffe P, Baes M, Maxwell P, Carmeliet P. Deficiency or inhibition of oxygen sensor Phd1 induces hypoxia tolerance by reprogramming basal metabolism. 2008;40:170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moser SC, Bensaddek D, Ortmann B, Maure J-F, Mudie S, Blow JJ, Lamond AI, Swedlow JR, Rocha S. PHD1 links cell-cycle progression to oxygen sensing through hydroxylation of the centrosomal protein Cep192. 2013;26:381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The Jackson Laboratory. Which JAX mouse model is best for atherosclerosis studies: Apoe or Ldlr knockout mice?. 2015. https://www.jax.org/news-and-insights/jax-blog/2013/november/which-jax-mouse-model-is-best-for-atherosclerosis-studies-apoe-or-ldlr-knoc (27 February 2016).

- 8. Selathurai A, Deswaerte V, Kanellakis P, Tipping P, Toh B-H, Bobik A, Kyaw T. Natural killer (NK) cells augment atherosclerosis by cytotoxic-dependent mechanisms. 2014;102:128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stewart FA, Heeneman S, Te Poele J, Kruse J, Russell NS, Gijbels M, Daemen M. Ionizing radiation accelerates the development of atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE-/- mice and predisposes to an inflammatory plaque phenotype prone to hemorrhage. 2006;168:649–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bakris GL, Yu K-HP, Leong R, Shi W, Lee T, Saikali K, Henry E, Neff TB. Late-breaking orals. 2012;14:487–489. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olson E, Demopoulos L, Haws TF, Hu E, Fang Z, Mahar KM, Qin P, Lepore J, Bauer TA, Hiatt WR. Short-term treatment with a novel HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (GSK1278863) failed to improve measures of performance in subjects with claudication-limited peripheral artery disease. 2014;19:473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rahtu-Korpela L, Karsikas S, Hörkkö S, Blanco Sequeiros R, Lammentausta E, Mäkelä KA, Herzig K-H, Walkinshaw G, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J, Serpi R, Koivunen P. HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase-2 inhibition improves glucose and lipid metabolism and protects against obesity and metabolic dysfunction. 2014;63:3324–3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. ClinicalTrials.gov. ClinicalTrials.gov – HIF-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in clinical trials. 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=prolyl+hydroxylase+CKD&Search=Search (16 January 2016).

- 14. Holliger P, Prospero T, Winter G. ‘Diabodies’: small bivalent and bispecific antibody fragments. 1993;90:6444–6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Musallam KM, Porter JB, Sfeir PM, Tamim HM, Richards T, Lotta LA, Peyvandi F, Jamali FR. Raised haematocrit concentration and the risk of death and vascular complications after major surgery. 2013;100:1030–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H. Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: a meta-analysis. 2007;369:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Veen JN, van Dijk TH, Vrins CLJ, van Meer H, Havinga R, Bijsterveld K, Tietge UJF, Groen AK, Kuipers F. Activation of the liver X receptor stimulates trans-intestinal excretion of plasma cholesterol. 2009;284:19211–19219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.