Abstract

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are cytoskeletal polymers that extend from the nucleus to the cell membrane, giving cells their shape and form. Abnormal accumulation of IFs is involved in the pathogenesis of number neurodegenerative diseases, but none as clearly as giant axonal neuropathy (GAN), a ravaging disease caused by mutations in GAN, encoding gigaxonin. Patients display early and severe degeneration of the peripheral nervous system along with IF accumulation, but it has been difficult to link GAN mutations to any particular dysfunction, in part because GAN null mice have a very mild phenotype. We therefore established a robust dorsal root ganglion neuronal model that mirrors key cellular events underlying GAN. We demonstrate that gigaxonin is crucial for ubiquitin–proteasomal degradation of neuronal IF. Moreover, IF accumulation impairs mitochondrial motility and is associated with metabolic and oxidative stress. These results have implications for other neurological disorders whose pathology includes IF accumulation.

Introduction

The accumulation of intermediate filaments (IFs) is one of the hallmarks of giant axonal neuropathy (GAN; OMIM #256850), a severe autosomal-recessive neurological disorder that causes progressive childhood- or infantile-onset degeneration of the peripheral and then central nervous system (1,2). The clinical features of GAN are accompanied by pathological neurodegeneration characterized by thickened or swollen neurons, hence the appellation ‘giant axonal neuropathy’ (1,3–5). This swelling is secondary to the accumulation, dense-packing and disorganization of neuronal IFs that form a network of 10 nm diameter cables that span the cell from the nucleus to the cell membrane (6). GAN is caused by mutations in GAN gene, encoding gigaxonin, a protein belonging to the BTB (Bric-a-brac, Tramtrack and Broad) Kelch family of E3 ligase adaptors (2). These proteins recruit substrates to a functional ubiquitination complex, which flags them for subsequent degradation (2,7); yet it has been difficult to link the loss of gigaxonin function to IF aggregation and subsequent neuronal degeneration.

The proteins composing IFs are exceedingly complex; they are encoded by ∼75 genes that fall into five major classes, each comprising individual subtypes based on their primary sequence (8). Some cell types, such as fibroblasts, express only a single sub-type that forms a homopolymer, while other cells, most notably neurons, express several IF proteins that form complex heteropolymers. In GAN, IFs of multiple types accumulate in a range of tissues—virtually all patients suffer from dermal keratoses and have characteristically kinky hair reflecting the involvement of keratins (IFs of Types I and II) (1,3–5), and dermal fibroblasts derived from GAN patients display aggregates of vimentin (IF Type III) (9). There is no doubt, however, that neurons bear the brunt of GAN pathology, and, fittingly, they have the most complex repertoire of IF. All neurons express a set of three proteins called the neurofilament triplet proteins that belong to the Type IV family (called light, middle and heavy, according to their molecular weight); some neurons also express another type IV IF called α internexin, and yet others, particularly those in the peripheral nervous system, express a type III IF protein called peripherin (10–13). To unravel the pathogenesis of GAN and the effects on these various IF proteins requires a tractable model system, but GAN−/− mice develop only subtle weakness and sensory deficits relatively late, at approximately 1 year of age (14–16). Their neuropathology is correspondingly modest, with varying levels of IF accumulation observed in different regions of the nervous system. No giant axons are visible in the peripheral nervous system, and detailed electron microscopic analyses is required to reveal IF accumulation and disarray (16). With these limitations it has been a challenge to understand pathogenic mechanisms underlying GAN at an organismal level.

In this study, we demonstrate that mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons provide an excellent experimental model system for manipulating gigaxonin levels and understanding GAN pathogenesis. We used this system to explore the effects of neuronal IF accumulation and the subcellular chain of events that links the loss of IF ubiquitination and clearance to cellular mechanisms underlying neuronal dysfunction and death. We find that IF accumulation specifically affects mitochondrial mobility and metabolism, and we show that replenishing gigaxonin can reverse subcellular IF and mitochondrial pathology. These results shed light on mitochondrial dysfunction in a range of neurological disorders where neuronal IF aggregation is a pathological leitmotif.

Results

IF accumulate in murine DRG neurons depleted of gigaxonin

Although GAN KO mice display only a mild phenotype, they do exhibit important features of GAN pathology at a cellular level (14). Given the prominent presenting feature of sensory deficits in patients, we decided to create a cellular model from DRG neurons from GAN null mice. DRG neurons are not only the first to succumb to GAN pathology but they are appealing as a model system because they express all subtypes of neuronal IF. Like all nerves they express the type IV neurofilament proteins α-Internexin (66 kDa) and the neurofilament triplet proteins NFL (68 kDa), NFM (160 kDa) and NFH (205 kDa), but they also express peripherin (57 kDa), which belongs to the type III IF family (10–13,17).

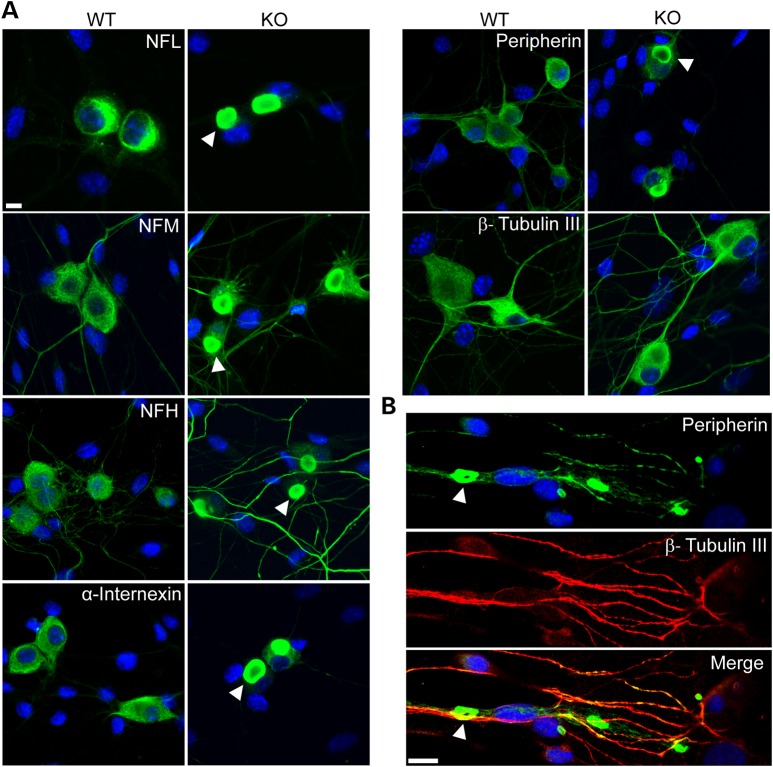

Although we expected some neurons to display IF accumulations, we were surprised to observe that ∼70% of DRG neurons showed IF accumulations after only 2 days in culture, reaching over ∼80% after 7 days (Fig. 1A). The perinuclear inclusions tended to be circular or oval with a diameter of ≥ 10 µm; neuritic inclusions detected in older cultures tended to be elongated or torpedo shaped (Fig. 1B shows accumulation of neuritic peripherin at day 21 culture, as an example).

Figure 1.

Neuronal IFs aggregate in DRG neurons from GAN KO mice. (A) DRG neurons show perinuclear accumulations of all neuronal IF subtypes (green) including NFL, NFM, NFH, α-internexin and peripherin at 7 days culture. Note that no aggregation of β-tubulin III was detected. (B) Peripherin IF (green) aggregates can be seen in neurites in older culture of 21 days. Nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). IF inclusions are indicated with arrowheads in both A and B. Scale bar: 10 µm.

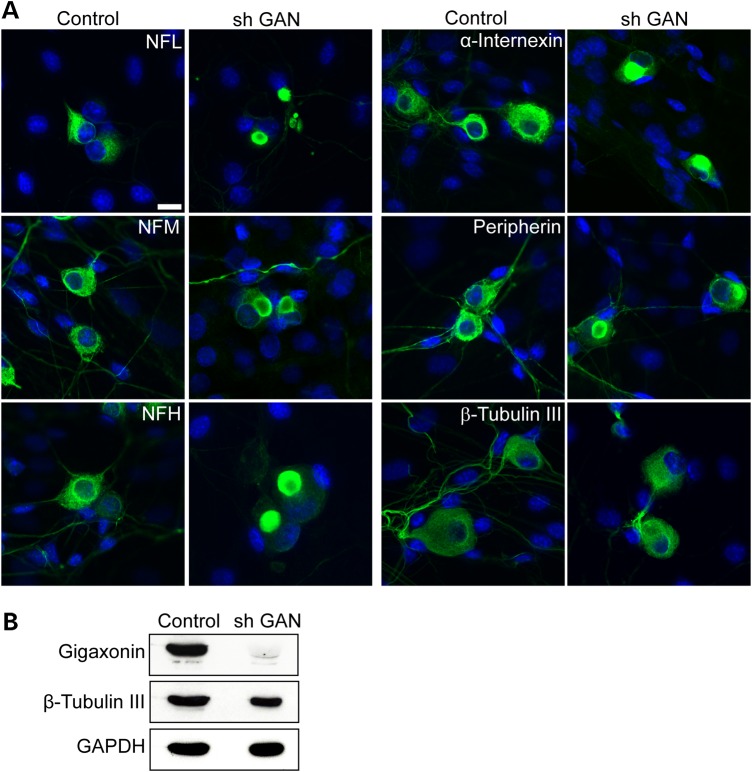

In addition to examining DRG neurons from GAN KO mice, we investigated whether acute deprivation of gigaxonin in DRG neurons from wild-type mice causes neuronal IF accumulation. Using shRNA lentivirus targeting GAN we achieved a ∼90% reduction in gigaxonin levels, which was accompanied by neuronal IF accumulation in ∼80% of neurons (Fig. 2). Gigaxonin depletion, whether early in development or in mature neurons, clearly causes IF accumulation in DRG neurons.

Figure 2.

Silencing GAN by shRNA produces IF aggregation in WT neurons. (A) Silencing of gigaxonin by shRNA GAN in cultured WT DRG neurons leads to aggregate formation of all neuronal IF (green) compared with Sh RNA control. Nuclei stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Western blot of lysate from WT DRG culture overexpressed with shRNA GAN, showing the level of gigaxonin reduction ∼90% of 7 days post infection. β-Tubulin III and GAPDH were used as loading controls.

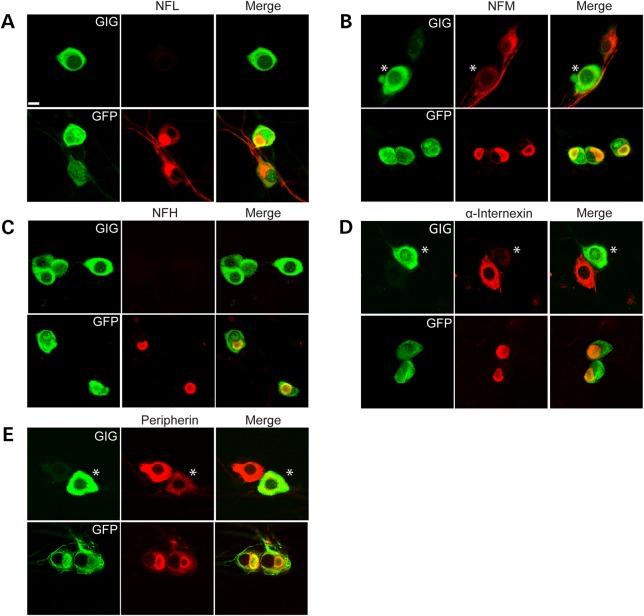

Gigaxonin overexpression clears IF accumulation in DRG neurons

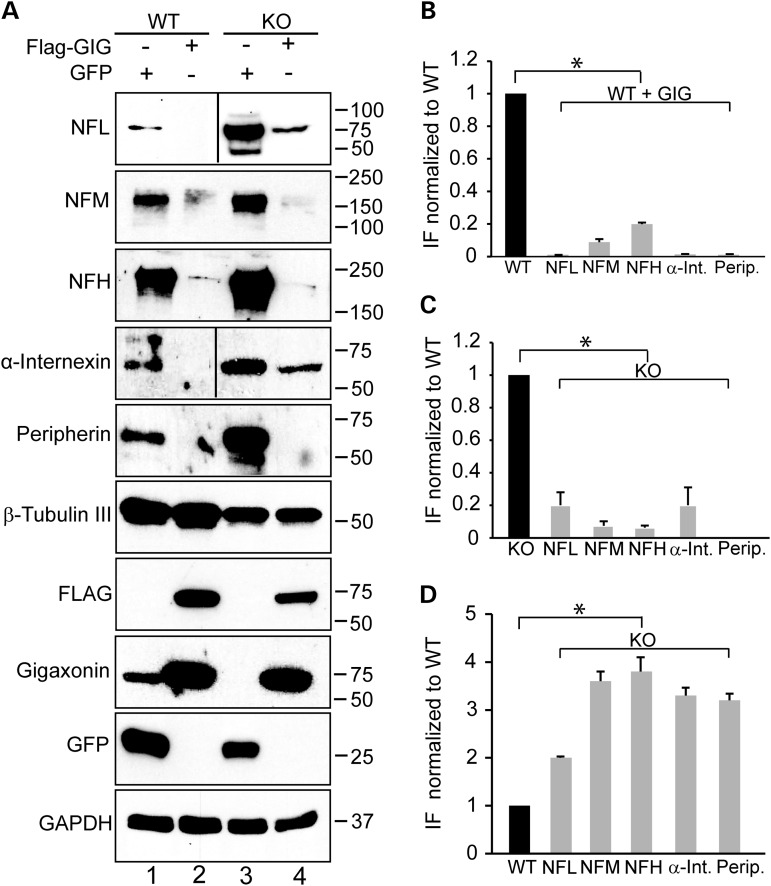

We next wished to test whether overexpression of gigaxonin can clear neurofilament aggregation in DRG neurons. We infected DRG neurons with a lentivirus expressing FLAG-gigaxonin or a control lentivirus expressing GFP. Seven days post infection, we analyzed DRG neurons by both microscopy and biochemistry. We found that expression of exogenous gigaxonin, visualized by its FLAG tag, completely cleared all IF aggregates in neurons (NFL, NFM, NFH, α-internexin and peripherin) (Fig. 3A–E). It is important to note that gigaxonin cleared both normal IF as well as aggregated neuronal IF. The number of cells showing inclusions reduced from over 80% to virtually none. The decrease in the levels of neuronal IF was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 4A–C). No changes in β-tubulin III levels were observed, demonstrating the selective role of gigaxonin in IF clearance. From these western blots it is also clear that the levels of the neurofilament triplet proteins are significantly higher in GAN KO mice compared with controls: NFL is approximately 2-fold higher, while NFM, NFH, peripherin and α-internexin were more than 3-fold higher (Fig. 4D).

Figure 3.

Overexpression of gigaxonin clears neuronal IF aggregation in GAN KO neurons. DRG neurons were transduced with lentiviruses that express either FLAG-tagged gigaxonin or GFP (as a control). There was a significant reduction in the levels of all subtypes of neuronal IF: NFL (A), NFM (B), NFH (C), α-internexin (D) and peripherin (E). Note that when cells expressed different levels of gigaxonin, then the cell with a greater expression of gigaxonin (asterisks) show decreased levels of the neuronal IF, as shown in B, D and E. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Figure 4.

Quantification of IF levels in GAN KO and WT overexpressing gigaxonin. (A) Immunoblot analysis of IF levels in DRG from WT and GAN KO mice overexpressing GFP as control neurons (lanes 1 and 3) or FLAG-gigaxonin (lanes 2 and 4). (B) IF levels are significantly reduced in DRG from WT mice when gigaxonin is overexpressed (comparison between lanes 1 and 2). (C) IF levels are significantly reduced in DRG from KO mice when gigaxonin is overexpressed (comparison between lanes 3 and 4). (D) Neuronal IF accumulates in DRG neurons of GAN KO mice (compare lanes 1 and 3). The levels of IF in all experiments were normalized to the levels of β-tubulin III. Experiments were conducted three times for each group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Intermediate filaments are degraded by the ubiquitin proteasomal pathway

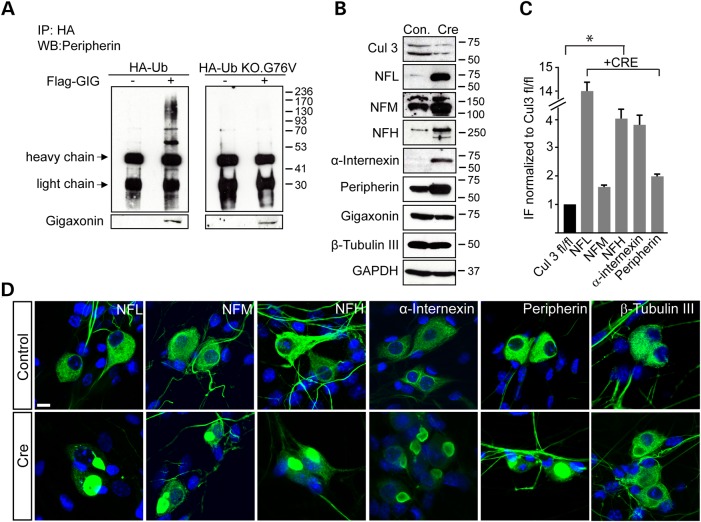

Gigaxonin is a member of the BTB Kelch family of E3 adaptor proteins that target substrates for protein degradation via ubiquitination (2,7). To determine whether gigaxonin is responsible for ubiquitination of neuronal IF, we transduced GAN KO neurons with HA-Ubiquitin with or without FLAG-gigaxonin. Cells were treated with proteasomal inhibitor N-acetyl-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-norleucinal (ALLN) so as to prevent the clearance of IF. Using peripherin as a prototypical IF, we would expect gigaxonin-dependent ubiquitination to cause it to run as a smear of ubiquitinated adducts. Indeed, this is what we observed (Fig. 5A, left panel).

Figure 5.

Intermediate filaments are ubiquitinated and degraded through a gigaxonin- Cul3 ubiquitin dependent pathway. (A) DRG cultures of GAN KO mice were transduced with HA-Ub (left panel) or HA-Ub KO.G76 V (right panel), with or without co-expression of FLAG-gigaxonin in the presence of the proteasomal inhibitor ALLN. Immunoprecipitation was performed by anti-HA antibody and western blot with anti-peripherin antibodies. (B) DRG from Cul3 fl/fl mice were cultured and infected with LV-CRE virus to deplete Cul3 (detected as a doublet protein between 50–75 kDa). Reduction of ∼70% in Cul3 level resulted in a significant elevation of all neuronal IF; β-tubulin III and GAPDH were used as loading controls. (C) Quantification of IF protein levels detected in western blot. Experiments were conducted three times for each group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. (D) Depletion of Cul3 (Cre) results in IF accumulations by immunofluorescence reminiscent to that seen in DRG neurons of GAN KO mice. Controls represent un-infected Cul3 fl/fl DRG neurons. Scale bar: 10 µm.

As a control we also transfected cells with HA-Ub G76 V.KO, a ubiquitin construct in which glycine 76, the last amino acid of ubiquitin that forms a bond with a lysine on the substrate, is mutated, along with all seven lysines (to arginines) to prevent the formation of a polyubiquitin chain. As can be seen in Figure 5A (right panel), with HA-pull down in GAN KO neurons no higher order structures were visible upon gigaxonin overexpression.

We took an independent approach to test whether the accumulation of IF occurs through loss of gigaxonin's presumed role as an adaptor to recruit substrates to the ubiquitin proteasome system: we tested whether depleting Cul3, another protein that binds to gigaxonin when it functions as an E3 adaptor (7) also causes neurofilament aggregation. This would demonstrate that gigaxonin indeed clears IF through its canonical role as a Cul3-based E3 ligase adaptor. For these experiments, we cultured DRG neurons from conditional Cul3 fl/fl mice and expressed Cre by viral transduction. We found that depleting Cul3 levels by ∼70% (note that Cul3 runs as a doublet, 18) (Fig. 5B)—does in fact increase the levels of neuronal IF (quantified in Fig. 5C) and lead to IF aggregation (Fig. 5D; typically >50% of cells show IF aggregates). We should point out that depleting Cul3 does not decrease the levels of gigaxonin. These results suggest that GAN does indeed act via a Cul3-E3 ligase adaptor complex.

IF aggregation disrupts mitochondrial dynamics

We next turned our attention to downstream subcellular events. We decided to look at mitochondria one of the normal roles of neurofilament polymers is to bind mitochondria and regulate their motility (19–21), and large IF aggregates could conceivably restrict this movement.

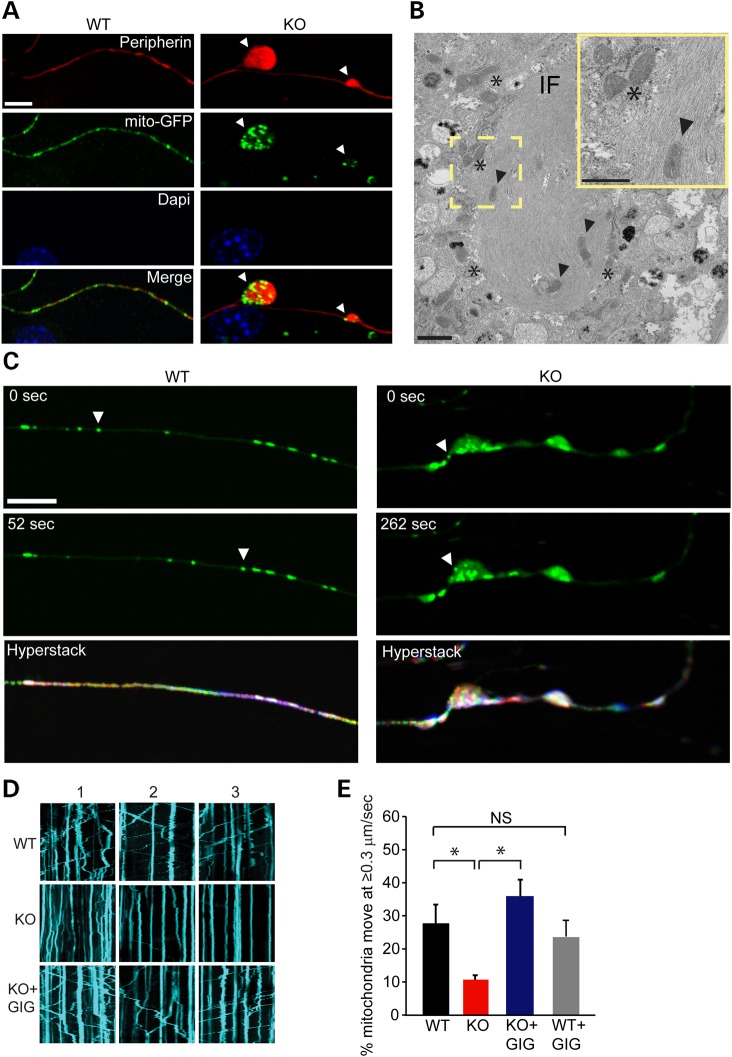

We first studied the localization of mitochondria in relation to IF aggregates. To visualize mitochondria, we expressed in DRG neurons the mitochondrially targeted fluorescent protein mito-GFP. Co-staining for GFP and peripherin revealed that mitochondria co-localized with IF axonal aggregates (Fig. 6A), often seen embedded or clustered within IF bundles (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Mitochondria are enriched at sites of IF accumulation and their motility is reduced in axons of GAN KO neurons. (A) DRG neurons cultured for 21 days and infected with mito-GFP lentivirus were fixed for Peripherin (red), GFP (mitochondria, green) and DAPI stained nuclei (blue). Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) TEM analysis of DRG cultures showing IF bundle with embedded (arrow heads) or clustered mitochondria (asterisks). Scale bar: 1 µm. Higher magnitude is shown in the yellow frame. Scale bar: 0.5 µm. (C) Arbitrary frames from movies of mitochondrial movement are shown as examples. In GAN KO neurons mitochondria particle were detected in axonal inclusion showing slow or no motility of mitochondria. All frames were stacked in ImageJ software and encoded with rainbow colour setting. Owing to the superposition of multiple colours, stationary mitochondria particles appear white, whereas moving mitochondria particles appear as rainbow-coloured paths at the end of seven minutes' exposure (hyperstack) Scale bar: 10 µm. (D) Representative tracking of mitochondria movement were also described as Kymographs. Straight kymographs indicate static mitochondria (higher level in KO) and moving mitochondria are described as diagonal kymographs. Replenishing gigaxonin by viral delivery of FLAG-gigaxonin restores mitochondrial movement (E) The percentage of mitochondria that show rapid movement (≥0.3 µm/s) was 28% (±5.6%) in WT axons (162 cells, 1562 mitochondria) compared with only 10% (±1.35%) in the GAN KO (134 cells, 2044 mitochondria). Replenishing gigaxonin by virally introducing FLAG-gigaxonin in GAN KO culture (KO + GIG) significantly increases the percentage of mitochondria that move 34% (±4.9%) (132 cells, 2028 mitochondria). No significant change (NS) in mitochondrial movement was detected between WT overexpressing FLAG-gigaxonin (WT + GIG, 87 cells, 1029 mitochondria) compare to mitochondrial movement in WT neurons. Experiments were conducted at least three times for each group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

We next tracked mito-GFP labeled mitochondria in real time to assess their motility (22). Focusing on the neuritic compartment, we found that mitochondria in GAN KO axons were static, suggesting that bundled IF impede mitochondrial transport in axons (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Material, Movie S1A and B). Mitochondrial motility was also visualized by kymographs showing static or slowly motile mitochondria in GAN KO neurons as compared with WT neurons (Fig. 6D). This phenotype was reversed by gigaxonin overexpression (Fig. 6D). DRG neurons from WT mice showed nearly three times as many mitochondria moving at ≥0.3 µm/s as DRG neurons from GAN KO mice (Fig. 6E). Restoration of gigaxonin expression in DRG neurons from GAN KO mice restored the velocity of mitochondria to a level 3.5 times higher than in GAN KO neurons without gigaxonin expression (Fig. 6E). No significant change in motility rate was detected in WT neurons overexpressing gigaxonin (Fig. 6E).

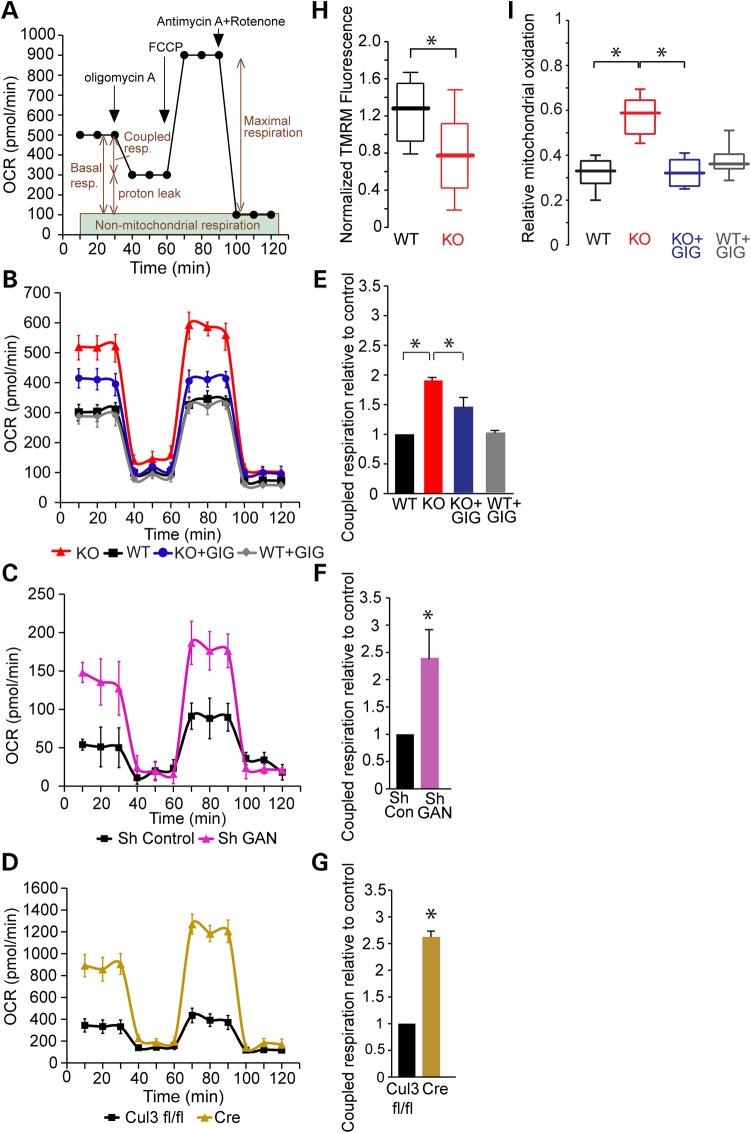

GAN knockout alters mitochondrial bioenergetics

We next tested the oxygen consumption rate (OCRs) of mitochondria using the Seahorse XF-24 metabolic flux analyzer. The advantage of this device is that it gives comprehensive information on several key respiratory parameters: basal respiration, proton leak (after inhibiting ATP synthase using oligomycin A) and maximal respiration (after using the mitochondrial un-coupler FCCP). We also assessed non-mitochondrial respiration using the complex 1 inhibitor rotenone in conjunction with the complex III inhibitor antimycin A (Fig. 7A). We explored the effects of neurofilament aggregation on metabolism in GAN KO (Fig. 7B) and WT DRG cultures depleted by shRNA for GAN (Fig. 7C). In addition, we tested for metabolic alterations in DRG culture where Cul3 has been depleted given that it produced a very similar phenotype with respect to IF accumulation (Fig. 7D). Surprisingly, we found that in all three paradigms (GAN KO, shRNA GAN and Cul3 depletion) there was a higher level of basal (1.9-, 3-, 3.5-fold, respectively) and maximal (4.5-, 2.4-, 3.6-fold, respectively) respiration compared with the controls. Since coupled respiration—defined as the oxygen consumption involved in mitochondrial ATP generation—is a good measure of mitochondrial ATP generation, we plotted coupled respiration demonstrating 1.9-, 2.4- and 2.6-fold higher rates in GAN KO (Fig. 7E), shRNA GAN (Fig. 7F), Cul3 depleted (Fig. 7G) cultures, respectively, compared with their controls. Replenishing gigaxonin in GAN KO neurons (by viral delivery of FLAG-gigaxonin) significantly decreased basal (2.3-fold), maximal (3.3-fold) and coupled respiration (1.4-fold) compared with GAN KO rates (Fig. 7B and E), consistent with a normalization of metabolic parameters.

Figure 7.

Mitochondria bioenergetics are altered in GAN KO cultures and accompanied by elevation in oxidative stress. (A) OCR was measured using XF24 Seahorse Biosciences Extracellular Flux Analyzer (see Materials and Methods). (B) OCR measurements of GAN KO and WT DRG cultures at baseline and after expression of FLAG-gigaxonin. (C) OCR measurements of WT DRG cultures after depleting gigaxonin by shRNA (Sh GAN) compared with Sh RNA control (Sh Control). (D) OCR measurements of Cul3-deficient DRG cultures (neurons from Cul3 fl/fl mice infected by lentivirus expressing Cre) compared with uninfected control (Cul3 fl/fl). (E) Coupled respiration rates of cultures described in B. Rates were normalized to WT control and plotted in graph. WT: 1; KO: 1.9 (±0.02); KO + GIG: 1.48 (±0.17): WT + GIG: 1 (±0.02). (F) Coupled respiration rates of cultures described in C normalized to Sh RNA control and plotted in graph. Sh Control: 1; sh GAN: 2.4 (±0.54). (G) Coupled respiration rates of cultures described in D normalized to Cul3 fl/fl-control and plotted in graph. Cul3 fl/fl:1 ; Cre: 2.62 (±0.11). (H) Mitochondrial membrane potential, as measured by TMRM fluorescence, was reduced in DRG neurons from GAN KO mice. Data are presented as box and whisker plots: WT: median 1.28, n = 16; GAN KO: median 0.77, n = 16; KO + GIG median 0.76, n = 19; WT + GIG median 1.14, n = 13. Statistical significance was determined by Mann–Whitney test. *P < 0.05. (I) DRG cultures were infected with adeno-viruses expressing mito-roGFP and oxidative stress was tested by ratiometric measurement of mitochondrial-ro-GFP signal. Relative mitochondrial oxidation presented as box and whisker plots shows approximately two times higher levels in GAN KO neurons compare with WT (WT: median 0.33, n = 21; KO: median 0.59, n = 18). Expression of FLAG-gigaxonin in GAN KO neurons reduced mitochondrial oxidation by ∼2-fold (KO + GIG: median 0.32, n = 20) to levels similar to WT neurons with no effect of expression on WT (WT + GIG: median 0.36, n = 13). Experiments were performed at least four times for each group and statistical significance was determined by Mann–Whitney test. *P < 0.05.

We next asked whether this increase in coupled respiration and ATP production was associated with alterations in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) potential, which is generated by the proton-pumping electron transport chain and controls the coupling between OCR and ATP generation. We measured IMM potential using the cationic dye TMRM, which exhibits a greater fluorescence intensity when IMM potential is more negative (23). For these experiments we focused on mitochondria in the soma since they are more static and easier to assess for the duration of the experiment. We found that TMRM signals in GAN KO neurons were 1.7-fold lower than the TMRM of WT neurons (Fig. 7H). The decrease in TMRM fluorescence in conjunction with the high rate of basal oxygen consumption in GAN KO compared with WT neurons suggests that ATP utilization is increased in the GAN KO cells.

Oxidative stress is elevated in mitochondria of GAN KO DRG neurons

One potential consequence of increased oxidative phosphorylation is an increase in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can lead to toxic sequelae (24). We therefore tested whether GAN KO neurons show an increase in the level of thiol oxidant stress. In order to assess oxidation in the mitochondria, we infected our cultures with an adenovirus carrying a redox-sensitive variant of GFP (ro-GFP) that incorporates a pair of surface-exposed cysteine residues so that disulphide bond formation (when oxidized) alters the fluorescence emissions during excitation at 410/470 nm. This allows for ratiometric, real-time visualization of oxidative stress (25,26). The ro-GFP was targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (mito-roGFP, Fig. 7I) to measure mitochondrial oxidation. The percent oxidation of roGFP was calibrated in each experiment by using DTT (to fully reduce the roGFP) and ALD (to fully oxidize the roGFP). Oxidation was significantly higher in the mitochondria in the GAN KO neurons than in WT neurons (Fig. 7I). Moreover, rescue of IF aggregation by overexpressing of FLAG-gigaxonin in GAN KO neurons attenuated oxidation levels in the mitochondria to the levels detected in WT control neurons (Fig. 7I). We observed no effect of gigaxonin expression on ROS levels in WT neurons (Fig. 7I).

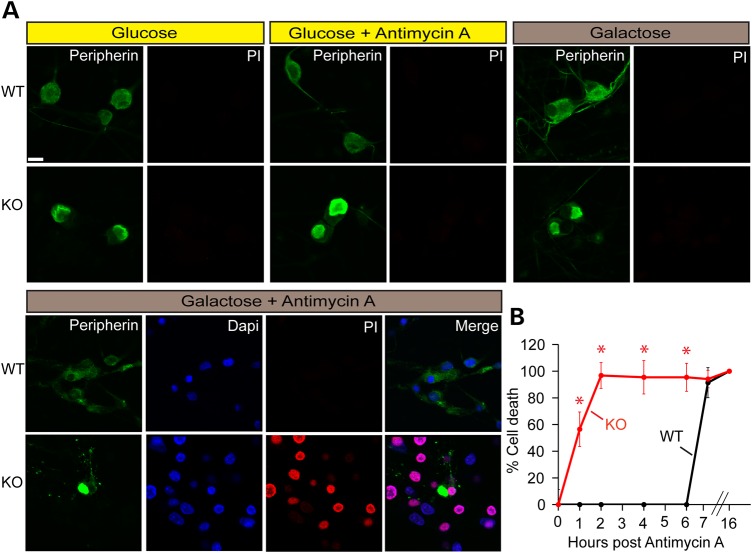

GAN KO DRG neurons are more vulnerable to mitochondrial stress than WT neurons

To determine whether GAN KO cells are vulnerable to higher metabolic demands, we tested cell survival under different metabolic inhibitions (Fig. 8). We found no cell death in WT or KO cultured cells growing under normal conditions (media containing glucose). Inhibition of mitochondrial function by antimycin A did not affect cell survival, demonstrating that GAN KO cells can survive utilizing glycolysis alone. When glycolysis is not an option, however, such as when growing cells on galactose (with no glucose), then GAN KO cells are more sensitive to mitochondrial inhibition, showing rapid cell death compared with wild-type neurons. These results are consistent with the increased metabolic demands of GAN KO neurons and the importance of their enhanced functioning mitochondria in enabling them to survive.

Figure 8.

Cell death assessment of GAN KO cells upon different metabolic conditions. Cell death of DRG cultures from WT and GAN KO mice was measured at different metabolic states by propidium iodide assay. (A) Metabolic media used were: regular Neurobasal medium (Glucose), Neurobasal medium with 100 µm antimycin A (glucose + antimycin A) added for 4 h, Neurobasal medium with neither glucose nor pyruvate but with galactose without (galactose) or with antimycin A (galactose + antimycin A). Medium with galactose (25 mm) was added to cultures 48 h before cell death assay. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-peripherin (green), propidium iodide (PI, red), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Cell death assay of DRG cultures maintained in galactose medium after different time points post treatment with antimycin A. Experiments were performed three times. Data are represented as mean ± SEM and statistical significance was determined by t-test. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Despite the discovery of fifteen years ago that mutations in GAN gene underline giant axonal neuropathy (1,2,5,27), it has thus far been difficult to link the loss of gigaxonin function to IF aggregation and subsequent neuronal degeneration. One impediment has been the limited pathological samples from human patients; another has been the relatively mild phenotype of GAN null mice. The mice do exhibit important features of GAN pathology at a cellular level, however, and we recently showed that IF aggregation can be productively studied in fibroblasts (9). Johnson-Kerner et al. (28) also showed accumulation of neurofilament light chain and peripherin using motor neurons derived from induced pluripotent cells (iPS) from GAN patients, but the modest levels of neuronal IF accumulation, the relative lack of dense IF aggregation, and the considerable expense required to generate and differentiate iPS neurons point to the need for better cell-based systems to study neuronal IF degradation.

In this study, we address this shortcoming by demonstrating that mouse DRG neurons provide a tractable approach to understanding the dysfunctions caused by loss of GAN, either by genetic deletion or suppression by shRNA. We show that gigaxonin is not only directly responsible for degradation of all neuronal IF but also functions as part of a Cul3-based E3 ligase complex. The primary structure of gigaxonin had suggested this possibility, but it had so far resisted experimental validation. Our results describing the rapid clearance of gigaxonin from neurons are especially impressive given that neuronal IF polymers are thermodynamically very stable. In fact, by some estimates neuronal IF have a half-life of approximately 2.5 months (29). These results help explain why gigaxonin is normally maintained at a very low level of expression for normal neuronal house-keeping purposes (30).

It is important to note that several other proteins have been implicated in the degradation of neuronal IF. These include the E3 ligase CHIP that plays a role in the degradation of NFM and the tripartite motif protein TRIM2 that plays a role in the degradation of NFL (31,32). It is unclear whether these proteins co-ordinate their activity with gigaxonin or whether their activities are increased compensatorily in the context of gigaxonin deficiency. The severe IF accumulation phenotype suggests that even if there is an attempt at compensation, it is vastly inadequate, and emphasizes the importance of gigaxonin as a master regulator of IF clearance. Moreover, as we show here gigaxonin singularly clears all neuronal IF. Indeed, this makes teleological sense given that IF subunits are extremely well-regulated stoichiometrically (33,34) and an imbalance of the levels of subunits causing by preferential degradation of only some neuronal IF subtypes would in itself cause aggregation.

This current work also appears to link IF aggregation in the context of GAN to subcellular events such as mitochondrial dysmotility and metabolic derangements. We already had hints of this from our most recent work in fibroblasts (35), but the inclusions are likely to serve especially as steric barriers in neurites with their thin caliber. Future experiments will be required to formally test the role of neurofilament aggregates in inhibiting axonal transport and the broader consequences of altered vesicular transport. Regardless, the mitochondrial pathology in GAN has enormous consequences for neurons, whose mitochondria must constantly move to locations where they are especially needed, such as synapses and the nodes of Ranvier, to produce ATP and buffer calcium (36,37). Mitochondrial dysmotility could provide one explanation for why peripheral nerves, which are the longest neurons in the body, are most vulnerable to disorders of axonal transport and are involved early and severely in GAN. It could also help explain why mice with their smaller size and correspondingly smaller neurons do not develop the severe pathophysiology of the human patients.

Even though the GAN KO mitochondria are poorly motile, they continue to respire, indeed with a higher OCR. We envisage that this is to compensate for their inability to provide ATP along the length of the neuron in an efficient manner. This increased oxygen consumption comes at a cost, however: the increased oxidative phosphorylation with a corresponding activation of molecular oxygen produces deleterious ROS. In addition, the increased metabolic demand renders neurons teetering on the brink of energy failure more susceptible to additional stressors. Each of these sequelae could set off multiplying toxic pathways; for instance, ROS could damage proteins, membrane lipids and DNA, adding stress and oxygen demands, at the same time damaging mitochondrial proteins that are working close to their functional capacity. These toxic pathways could thus create a vicious feed-forward reaction that could account for the rapidly progressive nature of the disease.

There are still a number of important questions that remain to be answered. In the context of neurodegeneration it would be important to test whether mitochondrial dysmotility and metabolic derangements occur preferentially in a few subtypes of neurons explaining cell specific vulnerability in this disease. It would also be important to test whether glia—in particular, astrocytes (that show GFAP inclusions called Rosenthal fibres) demonstrate metabolic changes given that gliosis and white matter changes have been observed in GAN patients (38–44).

Likewise, even though our experiments suggest that the absence of the E3 ligase adaptor gigaxonin, causes a build-up of IF subunits that form bundles of IF, there are still important mechanistic questions at the heart of the issue of IF disassembly and degradation that remain to be addressed: Does gigaxonin bind and recruit subunits away from the surface of the IF polymer? Is degradation coupled to disassembly processes that are typically orchestrated by phosphorylation of IF subunits (45)? Is there a change in the normal stoichiometry of neurofilament subunits within these IF bundles that make them aggregation prone—a phenomenon that has been observed to occur by experimentally altering the ratios of the different IF subunits (33)? Does the bundling of IF cause other pathological dysfunction from their role as integrators of signalling pathways that might adversely affect metabolic processes independent of mitochondria (46)? These questions are beyond the scope of the current study, but we now have the tools to address them. It is intriguing that in a recent study it appears that gigaxonin binds IF via its Kelch domain opening up a biochemical avenue to address gigaxonin–IF recruitment and subsequent degradation (47).

Our findings gain wider significance in light of the fact that neuronal IF aggregation is not just observed in this rare familial disorder, but indeed is a hallmark of a large array of neurological disorders, from degenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Lewy body dementia, neuronal IF inclusion disease, spinal muscular atrophy and some forms of Charcot–Marie–Tooth diseases, to neuropathic disorders resulting from metabolic and toxic insults stemming from diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency or organic solvent and acrylamide ingestion (5,10,48). In all these diseases, it has been difficult to dissect the contribution of IF accumulation to degeneration. By addressing the role of IF aggregation in GAN, it is likely that we will be able to draw valuable insights pertaining to degeneration in these myriad contexts.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of GAN knockout (GANΔexon1/Δexon1; henceforth GAN−/−) and Cullin 3 conditional knockout mice (Cul3 fl/fl) has been previously described (14,18). Mice were housed in a specific pathogen free (SPF) facility and all experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Northwestern University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

DRG primary neurons

DRG neurons were isolated from 3- to 5-day-old mice using established protocols with a few modifications (49). Briefly, DRG neurons were dissected and placed in a 37°C Hibernate A medium (BrainBits, Springfield, IL) containing 35 U papain/ml (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ). Following a 3 min centrifugation at 200g, the pellets containing neurons were resuspended and incubated for 10 min at 37°C in Hibernate A medium containing Collagenase type II (4 mg/ml; Worthington) and Dispase type II (4.6 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). An additional centrifugation step was performed and cells were re-suspended in Neurobasal-A medium (that contains 25 mm d-glucose) supplemented with B27 (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 0.5 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. To select for dissociated neurons, the re-suspended cells were filtered through a 100 µm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and then plated onto polyethylenimine (Sigma) coated coverslips placed in 24- or 6-well plates (at a density of 100 000 or 300 000 cells per well, respectively). Primary neurons were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. To preserve conditioning of the media only 25% of the old media was replaced with fresh media twice a week. In experiments where cells were forced to produce ATP without glucose, regular Neurobasal A medium was replaced with a d-glucose and sodium pyruvate free version (Gibco) that contained 25 mm galactose as an energy source.

Lentiviruses and constructs.

The lentiviral vector FCIV with a ubiquitin C promoter (50) was used to express FLAG-tagged gigaxonin and GFP (both cloned into XbaI and EcoRI sites), HA-ubiquitin (cloned from addgene#18712 into XbaI and EcoRI sites) (51) and HA-ubiquitin KO G76V (cloned from addgene#11932 into XbaI and SbfI sites) (52). For live-cell imaging of mitochondria we used the same vector to express GFP fused to the mitochondrial-targeting sequence of subunit VIII of human cytochrome c oxidase (mito-GFP) (53) (The mito-GFP cassette was PCR cloned into the XbaI and EcoRI sites of FCIV from the pSL6-CMV vector; a kind gift of Dr R.S. Morrison, University of Washington) (53). For silencing GAN in DRG primary neurons we used lentivector pLKO.1 that expresses shRNA targeting GAN (henceforth called shRNA GAN) under the phosphoglycerate kinase promoter (MISSION® vector TRC # TRCN0000251146, Sigma) and a control vector that expresses an shRNA that does not target any known mammalian RNA (#SHC002, Sigma). For delivering Cre to primary neurons we used the lentiviral construct LV-CRE (Addgene#12106) (54).

Lentivirus production and transduction

All lentiviruses were produced in HEK293T cells grown in DMEM high glucose medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS; 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. HEK293 T cells were transfected with the relevant lentiviral construct along with the packaging vectors—pCMV-VSV-G and pCMV Gag/Pol—using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) (55). The supernatants containing virus particles were collected 48–72 h post transfection, filtered through a 0.45 µm filter and concentrated by a Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The relative infectivity of viral particles was determined by the multinuclear activation of a galactosidase indicator (MAGI) assay (56). Briefly, HeLa-CD4+-LTR-βgal cells (NIH AIDS Reagent Program, catalog no. 1470) were infected with several virus dilutions and after 48 h, the cells were stained with X gal (Sigma); the blue cells arising from acquired βgal activity were counted. Infectivity was calculated by multiplication of the number of positive stained cells and the virus dilution and determined as U/ml. DRG cultures were transduced with viruses (at a titer of 5 U/cell as described in 57) on 2–4 days in vitro (DIV) and experiments were conducted 7–9 days post infection. Under these conditions >90% of the neurons were infected as determined by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Primary antibodies

We used the following primary antibodies: anti-NFL (Cat#MCA-DA2, EnCor Biotechnology, Gainesville, FL), anti-NFM (Cat#CPCA-NF-M; EnCor Biotechnology), anti-NFH (Cat#CPCA-NF-H; EnCor Biotechnology), anti-Peripherin (Cat#AB1530, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-α-Internexin (Cat#RCPA-a-int; Encor Biotechnology), anti-gigaxonin (Cat#SAB4200104; Sigma), anti-Flag (monoclonal Cat#F1804; Sigma; polyclonal Cat#F7425; Sigma), anti-β-Tubulin III (monoclonal #MAB1637, EMD Millipore; polyclonal #T2200; Sigma), anti-Cullin 3 (Cat#2759; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-GAPDH (Cat#14C10; Cell Signaling), anti-GFP (Cat#11814460001; Roche) and anti HA (Cat#3724, Cell Signaling).

Immunofluorescence assay

To visualize IF by immunofluorescence, neurons were fixed in −20°C methanol for 7 min; then exposed to a blocking solution of 5% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min, before being incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody diluted in blocking solution. Following two washes with PBS-T (0.05% Tween 20) and three with PBS, the cells were stained with fluorophore conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and washed again similarly. For mitochondrial studies, neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min at room temperature followed by a 10 s permeabilization with −20°C methanol, three washes in 50 mm glycine (in PBS) and three washes in PBS before processing for immunofluorescence staining as described above. The cover slips were then mounted on slides in Prolong© Gold with DAPI to stain nuclei (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Images were obtained using a CTR6500 confocal microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) equipped with Leica LAS AF software.

Immunoblotting assay

DRG neurons were scraped from the culture dish, washed twice with PBS and lysed by boiling in 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) in 100 mm Tris–Cl pH 7.4 for 10 min. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA 58). Protein extracts were prepared with Laemmli buffer (59), boiled for 5 min and separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel before being electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, which were then blotted sequentially with the appropriate primary antibody and the horse radish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies before detection using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Detection kit (Thermo Scientific). Images were quantified with ImageJ-based software (National Institutes of Health) (60).

Ubiquitination assay

DRG KO neurons were infected with lentiviruses expressing HA-Ub or HA-Ub.G76V. In some experiments, the neurons were also co-infected with FLAG-tagged gigaxonin. Seven hours post-infection, cells were treated for 16 h with the proteasome inhibitor 5 µm ALLN (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA). Before harvesting, the cells were washed with PBS, lysed in 1% SDS in 100 mm Tris–Cl and boiled for 10 min. Samples (100 µg) were diluted 1:7 with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer without SDS (10 mm Tris–Cl pH 8, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5 mm ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 140 mm NaCl) containing 2 mm N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma), 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 20 mm sodium fluoride, 100 mm β-glycerophosphate and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Cell lysates were pre-cleared by rotation with protein-G PLUS-agarose beads (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) for 1 h at 4°C. Following a 5 min spin at 20 000g at 4°C, the clarified lysates were incubated in a rotary shaker with anti HA-antibody to form protein–antibody complexes (16 h, 4°C). Protein G beads were then added and the mixture was additionally incubated for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer and then boiled in Laemmli buffer prior to loading on SDS gels.

Electron microscopy

Cultured DRG neurons were fixed in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) containing 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Cultures were post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer, rinsed with water and stained with 3% uranyl acetate, followed by a rinse with water and subsequent dehydration in ethanol of ascending grades (50, 70, 80, 90 and 100%) (61). Cultures were then embedded in resin mixture of Embed 812 kit (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and cured in a 60°C oven. Sample blocks were sectioned into 70 nm sections on a Leica Ultracut UC6 ultramicrotome and the sections were collected on 200 mesh Cu grids before being stained with 3% uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate (61).

Mitochondrial motility

DRG neurons were cultured on 35 mm glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek) and infected with FCIVmito-GFP to visualize mitochondria. Spinning disk confocal microscopy was performed using an Andor XDI Revolution microscope (60× oil-immersion objective) equipped with MetaMorph software. Images were captured every 2 s for 7 min. Movies of mitochondrial movement were opened in ImageJ (NIH) (60) and 100 µm segments were tracked by DiaTrack 3.1 software (version 3.01; Semasopht, North Epping, Australia) (62) to tabulate and graph the number and velocity of mitochondria. Instantaneous velocity was calculated based on the movement of individual mitochondria over each 2 s time frame. A cut-off threshold of 0.1 µm/s was used to exclude non-motile mitochondria (63) (∼60% of mitochondrial are non-motile). The rest of the mitochondria were divided into two groups: those that move at <0.3 µm/s and those that move at ≥0.3 µm/s (64). Differential movement of the fast migrating group as a percentage of this number was graphed to compare velocities of GAN KO versus WT control mitochondria and kymographs were generated by ImageJ (Multi Kymograph plugin; J. Rietdorf, FMI Basel and A. Seitz, EMBL Heidelberg) (65).

OCR measurements

OCRs were measured utilizing the XF24 Seahorse Biosciences Extracellular Flux Analyzer. 105 cells were plated in each well and analyzed 3 days later. In overexpression experiments, cells were infected with FCIV virus expressing the relevant construct one day after plating and analyzed 3 days post-infection. In knock-down experiments, DRG were also infected with shRNA, or in the case of Cul 3 fl/fl with LV-CRE virus, one day after plating, but were analyzed 7 days post infection. 30 min prior to running the assay, the media were changed to 500 μl of fresh Neurobasal A media. All mitochondrial respiration rates were calculated by subtraction of non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption—determined by inhibiting the electron transport of the mitochondria with the complex III inhibitor antimycin A (Sigma, 1 μm) and the complex I inhibitor rotenone (Sigma, 1 μm), both of which block oxidative phosphorylation—from the total OCR. The basal mitochondrial respiration was assessed at baseline by measuring oxygen consumption per minute (OCR). OCR associated with proton leak was determined after inhibition of the ATP synthase with oligomycin A (Sigma, 1.5 µm). Coupled respiration, defined as the oxygen consumption involved in mitochondrial ATP production, was determined by subtracting OCR associated with proton leak from basal OCR. Maximal respiration was the OCR after treating cells with the protonophore carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 5 μm) that uncouples mitochondrial ATP generation from oxygen consumption. At the end of each assay the cells were washed with PBS and lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer. To normalize for total protein content per well, protein concentration was measured by Bradford protein assay (Biorad 58). Statistical analysis was determined by the unpaired t-test.

Cell death assay

DRG cultures were incubated with 5 μg/ml propidium iodide (Life technologies) for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 and stained as described earlier (66). Cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at 4°C and 10 min room temperature followed by permeabilization for 10 s at −20°C methanol. Cells were then washed in 50 mm glycine in PBS and PBS (three times each wash) and were co-stained with anti-peripherin antibody. Dead cells stained with propidium iodide were counted under the microscope at 561 nm excitation/615 nm emission and plotted into a graph.

Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester mitochondrial imaging

Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) assay was used to determine mitochondrial membrane potential as previously described (23). Briefly, DRG cultures were incubated in the culture media with non-quenching concentration of TMRM (25 nm) (Life Technologies) for 20 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cultures were transferred to an imaging chamber (maintained at physiological temperature; 34–35°C) mounted on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71) running MetaFluor imaging software (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA). Cells were imaged with a cooled CCD camera (I-PentaMax, Princeton Instruments; Trenton, NJ). The imaging chamber was superfused with carbogen-saturated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 125 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 25 mm NaHCO3, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 25 mm d(+) glucose, 10 nm TMRM, pH 7.4, osmolality ∼310 mOsm/L at a flow rate of 2–3 ml/min. Cultures were left in the chamber for at least 10 min before any imaging was started in order for the cells to equilibrate with ACSF. Cells were imaged using a 40×/1.35NA oil-immersion objective (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Regions of interest (ROIs) were chosen in the soma of neurons. Fluorescent signals (F) were acquired using a 545 nm excitation filter, and emission was monitored at 580 nm. Images were taken every 20 s with 100 ms exposure time. The cells were incubated with 1 µm carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (Tocris Biosciences; Minneapolis, MN) to get the minimum fluorescence (FFCCP). The normalized TMRM fluorescence (ΔF) was then calculated using the equation: ΔF= (F −FFCCP)/FFCCP. The maximum fluorescence of each individual pixel was calculated using ImageJ. Statistical analysis was determined by non-parametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney rank-sum test.

Mitochondrial matrix redox measurements

To measure ROS, we expressed roGFP—a modified GFP construct—engineered to give a read-out on the reduction/oxidation state in mitochondria (mito-roGFP) using adenoviral delivery (25,26). DRG cultures were infected with adenovirus expressing mito-roGFP under the control of the CMV promoter for 24–36 h. Cells were then transferred to the same microscope system as described for the TMRM studies. ROIs in the neuronal soma were selected and ratiometric imaging was performed (excitation at 410 and 470 nm using filters mounted on a Lambda 10–2 filter wheel (Sutter Instruments; Novato, CA); emission was monitored at 535 nm). Images were taken every 60 s with exposure time of 600 ms. Results were reported as the ratio of F470/F410. After each experiment, mito-roGFP were fully reduced with 2 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), and further fully oxidized with 100 µm aldrithiol-4 (ALD). DTT and ALD were applied to establish the dynamic range of roGFP. Relative oxidation was calculated as 1−[(F − FALD)/(FDTT− FALD)], where 0 describes un-detectable oxidation and 1 describes full oxidation. Because of the ratiometric properties of roGFP, this number is independent of the expression level of the reporter construct or optics. Statistical analysis was determined by non-parametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney rank-sum test.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01NS062051 and 1R01NS082351]. The project was also helped by seed funding from the Hannah's Hope fund. The Goldman Laboratory is funded by grants from Hannah's Hope Fund and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (National Institutes of Health grant number PO1GM096971).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Opal lab for their intellectual input, Vicky Brandt for editorial assistance, Jessica Huang for help with histopathology and mouse genotyping, Tammy McGuire for her assistance with DRG culture, Dr Richard Miller for providing equipment for live fluorescence imaging, Dr Vladimir Gelfand for help with mitochondrial motility assays, and members of Dr Navdeep Chandel and Dr Dimitri Krainc labs for help with analysis of metabolic data. Imaging work for mitochondrial motility was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. Spinning disk confocal microscopy was performed on an Andor XDI Revolution microscope, purchased through the support of NCRR 1S10 RR031680-01.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Yang Y., Allen E., Ding J., Wang W. (2007) Giant axonal neuropathy. Cell Mol. Life Sci., 64, 601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bomont P., Cavalier L., Blondeau F., Ben Hamida C., Belal S., Tazir M., Demir E., Topaloglu H., Korinthenberg R., Tuysuz B. et al. (2000) The gene encoding gigaxonin, a new member of the cytoskeletal BTB/kelch repeat family, is mutated in giant axonal neuropathy. Nat. Genet., 26, 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asbury A.K., Gale M.K., Cox S.C., Baringer J.R., Berg B.O. (1972) Giant axonal neuropathy—a unique case with segmental neurofilamentous masses. Acta Neuropathol., 20, 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg B.O., Rosenberg S.H., Asbury A.K. (1972) Giant axonal neuropathy. Pediatrics, 49, 894–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson-Kerner B.L., Roth L., Greene J.P., Wichterle H., Sproule D.M. (2014) Giant axonal neuropathy: an updated perspective on its pathology and pathogenesis. Muscle Nerve, 50, 467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrmann H., Strelkov S.V., Burkhard P., Aebi U. (2009) Intermediate filaments: primary determinants of cell architecture and plasticity. J. Clin. Invest., 119, 1772–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pintard L., Willems A., Peter M. (2004) Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases: Cul3-BTB complexes join the family. EMBO J., 23, 1681–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksson J.E., Dechat T., Grin B., Helfand B., Mendez M., Pallari H.M., Goldman R.D. (2009) Introducing intermediate filaments: from discovery to disease. J. Clin. Invest., 119, 1763–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahammad S., Murthy S.N., Didonna A., Grin B., Israeli E., Perrot R., Bomont P., Julien J.P., Kuczmarski E., Opal P. et al. (2013) Giant axonal neuropathy-associated gigaxonin mutations impair intermediate filament protein degradation. J. Clin. Invest., 123, 1964–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liem R.K., Messing A. (2009) Dysfunctions of neuronal and glial intermediate filaments in disease. J. Clin. Invest., 119, 1814–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan A., Sasaki T., Kumar A., Peterhoff C.M., Rao M.V., Liem R.K., Julien J.P., Nixon R.A. (2012) Peripherin is a subunit of peripheral nerve neurofilaments: implications for differential vulnerability of CNS and peripheral nervous system axons. J. Neurosci., 32, 8501–8508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan A., Rao M.V., Veeranna ., Nixon R.A. (2012) Neurofilaments at a glance. J. Cell Sci., 125, 3257–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan A., Rao M.V., Sasaki T., Chen Y., Kumar A., Veeranna, Liem R.K., Eyer J., Peterson A.C., Julien J.P. et al. (2006) Alpha-internexin is structurally and functionally associated with the neurofilament triplet proteins in the mature CNS. J. Neurosci., 26, 10006–10019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dequen F., Bomont P., Gowing G., Cleveland D.W., Julien J.P. (2008) Modest loss of peripheral axons, muscle atrophy and formation of brain inclusions in mice with targeted deletion of gigaxonin exon 1. J. Neurochem., 107, 253–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding J., Allen E., Wang W., Valle A., Wu C., Nardine T., Cui B., Yi J., Taylor A., Jeon N.L. et al. (2006) Gene targeting of GAN in mouse causes a toxic accumulation of microtubule-associated protein 8 and impaired retrograde axonal transport. Hum. Mol. Genet., 15, 1451–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganay T., Boizot A., Burrer R., Chauvin J.P., Bomont P. (2011) Sensory-motor deficits and neurofilament disorganization in gigaxonin-null mice. Mol. Neurodegener., 6, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lariviere R.C., Julien J.P. (2004) Functions of intermediate filaments in neuronal development and disease. J. Neurobiol., 58, 131–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEvoy J.D., Kossatz U., Malek N., Singer J.D. (2007) Constitutive turnover of cyclin E by Cul3 maintains quiescence. Mol. Cell Biol., 27, 3651–3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirokawa N. (1982) Cross-linker system between neurofilaments, microtubules, and membranous organelles in frog axons revealed by the quick-freeze, deep-etching method. J. Cell Biol., 94, 129–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leterrier J.F., Rusakov D.A., Nelson B.D., Linden M. (1994) Interactions between brain mitochondria and cytoskeleton: evidence for specialized outer membrane domains involved in the association of cytoskeleton-associated proteins to mitochondria in situ and in vitro. Microsc. Res. Tech., 27, 233–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner O.I., Lifshitz J., Janmey P.A., Linden M., McIntosh T.K., Leterrier J.F. (2003) Mechanisms of mitochondria-neurofilament interactions. J. Neurosci., 23, 9046–9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz T.L. (2013) Mitochondrial trafficking in neurons. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol., 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteith A., Marszalec W., Chan P., Logan J., Yu W., Schwarz N., Wokosin D., Hockberger P. (2013) Imaging of mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial responses in cultured rat hippocampal neurons exposed to micromolar concentrations of TMRM. PLoS ONE, 8, e58059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auten R.L., Davis J.M. (2009) Oxygen toxicity and reactive oxygen species: the devil is in the details. Pediatr. Res., 66, 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanson G.T., Aggeler R., Oglesbee D., Cannon M., Capaldi R.A., Tsien R.Y., Remington S.J. (2004) Investigating mitochondrial redox potential with redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators. J. Biol. Chem., 279, 13044–13053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dooley C.T., Dore T.M., Hanson G.T., Jackson W.C., Remington S.J., Tsien R.Y. (2004) Imaging dynamic redox changes in mammalian cells with green fluorescent protein indicators. J. Biol. Chem., 279, 22284–22293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bomont P., Ioos C., Yalcinkaya C., Korinthenberg R., Vallat J.M., Assami S., Munnich A., Chabrol B., Kurlemann G., Tazir M. et al. (2003) Identification of seven novel mutations in the GAN gene. Hum. Mutat., 21, 446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson-Kerner B.L., Ahmad F.S., Diaz A.G., Greene J.P., Gray S.J., Samulski R.J., Chung W.K., Van Coster R., Maertens P., Noggle S.A. et al. (2015) Intermediate filament protein accumulation in motor neurons derived from giant axonal neuropathy iPSCs rescued by restoration of gigaxonin. Hum. Mol. Genet., 24, 1420–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan A., Sasaki T., Rao M.V., Kumar A., Kanumuri V., Dunlop D.S., Liem R.K., Nixon R.A. (2009) Neurofilaments form a highly stable stationary cytoskeleton after reaching a critical level in axons. J. Neurosci., 29, 11316–11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleveland D.W., Yamanaka K., Bomont P. (2009) Gigaxonin controls vimentin organization through a tubulin chaperone-independent pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet., 18, 1384–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q., Song F., Zhang C., Zhao X., Zhu Z., Yu S., Xie K. (2011) Carboxyl-terminus of Hsc70 interacting protein mediates 2,5-hexanedione-induced neurofilament medium chain degradation. Biochem. Pharmacol., 81, 793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balastik M., Ferraguti F., Pires-da Silva A., Lee T.H., Alvarez-Bolado G., Lu K.P., Gruss P. (2008) Deficiency in ubiquitin ligase TRIM2 causes accumulation of neurofilament light chain and neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 12016–12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straube-West K., Loomis P.A., Opal P., Goldman R.D. (1996) Alterations in neural intermediate filament organization: functional implications and the induction of pathological changes related to motor neuron disease. J. Cell Sci., 109 (Pt 9), 2319–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Julien J.P. (1999) Neurofilament functions in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol., 9, 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowery J., Jain N., Kuczmarski E.R., Mahammad S., Goldman A., Gelfand V.I., Opal P., Goldman R.D. (2015) Abnormal intermediate filament organization alters mitochondrial motility in giant axonal neuropathy fibroblasts. Mol. Biol. Cell, 27, 608–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheng Z.H., Cai Q. (2012) Mitochondrial transport in neurons: impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci., 13, 77–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schon E.A., Przedborski S. (2011) Mitochondria: the next (neurode)generation. Neuron, 70, 1033–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peiffer J., Schlote W., Bischoff A., Boltshauser E., Muller G. (1977) Generalized giant axonal neuropathy: a filament-forming disease of neuronal, endothelial, glial, and Schwann cells in a patient without kinky hair. Acta Neuropathol., 40, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alkan A., Kutlu R., Sigirci A., Baysal T., Altinok T., Yakinci C. (2003) Giant axonal neuropathy: MRS findings. J. Neuroimaging, 13, 371–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brockmann K., Pouwels P.J., Dechent P., Flanigan K.M., Frahm J., Hanefeld F. (2003) Cerebral proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of a patient with giant axonal neuropathy. Brain Dev., 25, 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pena S.D. (1982) Giant axonal neuropathy: an inborn error of organization of intermediate filaments. Muscle Nerve, 5, 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar K., Barre P., Nigro M., Jones M.Z. (1990) Giant axonal neuropathy: clinical, electrophysiologic, and neuropathologic features in two siblings. J. Child Neurol., 5, 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kretzschmar H.A., Berg B.O., Davis R.L. (1987) Giant axonal neuropathy. A neuropathological study. Acta Neuropathol., 73, 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas C., Love S., Powell H.C., Schultz P., Lampert P.W. (1987) Giant axonal neuropathy: correlation of clinical findings with postmortem neuropathology. Ann. Neurol., 22, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eriksson J.E., Opal P., Goldman R.D. (1992) Intermediate filament dynamics. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 4, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pallari H.M., Eriksson J.E. (2006) Intermediate filaments as signaling platforms. Sci. STKE, 2006, pe53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson-Kerner B.L., Garcia Diaz A., Ekins S., Wichterle H. (2015) Kelch domain of gigaxonin interacts with intermediate filament proteins affected in giant axonal neuropathy. PLoS ONE, 10, e0140157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cairns N.J., Lee V.M., Trojanowski J.Q. (2004) The cytoskeleton in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Pathol., 204, 438–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malin S.A., Davis B.M., Molliver D.C. (2007) Production of dissociated sensory neuron cultures and considerations for their use in studying neuronal function and plasticity. Nat. Protoc., 2, 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeanneteau F., Garabedian M.J., Chao M.V. (2008) Activation of Trk neurotrophin receptors by glucocorticoids provides a neuroprotective effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 4862–4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamitani T., Kito K., Nguyen H.P., Yeh E.T. (1997) Characterization of NEDD8, a developmentally down-regulated ubiquitin-like protein. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 28557–28562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dantuma N.P., Groothuis T.A., Salomons F.A., Neefjes J. (2006) A dynamic ubiquitin equilibrium couples proteasomal activity to chromatin remodeling. J. Cell Biol., 173, 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uo T., Dworzak J., Kinoshita C., Inman D.M., Kinoshita Y., Horner P.J., Morrison R.S. (2009) Drp1 levels constitutively regulate mitochondrial dynamics and cell survival in cortical neurons. Exp. Neurol., 218, 274–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfeifer A., Brandon E.P., Kootstra N., Gage F.H., Verma I.M. (2001) Delivery of the Cre recombinase by a self-deleting lentiviral vector: efficient gene targeting in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 11450–11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiscornia G., Singer O., Verma I.M. (2006) Production and purification of lentiviral vectors. Nat. Protoc., 1, 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimpton J., Emerman M. (1992) Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated beta-galactosidase gene. J. Virol., 66, 2232–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li M., Husic N., Lin Y., Christensen H., Malik I., McIver S., LaPash Daniels C.M., Harris D.A., Kotzbauer P.T., Goldberg M.P. et al. (2010) Optimal promoter usage for lentiviral vector-mediated transduction of cultured central nervous system cells. J. Neurosci. Methods, 189, 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradford M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem., 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laemmli E.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B. et al. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods, 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bozzola J.J. (2014) Conventional specimen preparation techniques for transmission electron microscopy of cultured cells. Methods Mol. Biol., 1117, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuzmenko A., Tankov S., English B.P., Tarassov I., Tenson T., Kamenski P., Elf J., Hauryliuk V. (2011) Single molecule tracking fluorescence microscopy in mitochondria reveals highly dynamic but confined movement of Tom40. Sci. Rep., 1, 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Misko A., Jiang S., Wegorzewska I., Milbrandt J., Baloh R.H. (2010) Mitofusin 2 is necessary for transport of axonal mitochondria and interacts with the Miro/Milton complex. J. Neurosci., 30, 4232–4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris R.L., Hollenbeck P.J. (1995) Axonal transport of mitochondria along microtubules and F-actin in living vertebrate neurons. J. Cell Biol., 131, 1315–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X., Schwarz T.L. (2009) Imaging axonal transport of mitochondria. Methods Enzymol., 457, 319–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aras M.A., Hartnett K.A., Aizenman E. (2008) Assessment of cell viability in primary neuronal cultures. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci., Chapter 7, Unit 7.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.