Abstract

Secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) reaches the airway lumen by local transcytosis across airway epithelial cells or with tracheobronchial submucosal gland secretions. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), deficiency of SIgA on the airway surface has been reported, however, reduction of SIgA levels in sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) has not been consistently observed. To explain this discrepancy, we analyzed BAL fluid and lung tissue from patients with COPD and control subjects. Immunohistochemical analysis of large and small airways of COPD patients showed MUC5AC was the predominant mucin expressed by airway epithelial cells, whereas MUC5B was expressed in submucosal glands of large airways. In addition to showing a reduction of IgA on the airway surface, dual immunostaining with anti-IgA and anti-MUC5B antibodies showed an accumulation of IgA within MUC5B-positive luminal mucus plugs, suggesting that luminal SIgA originates from submucosal glands in COPD patients. Although the concentration of SIgA in BAL inversely correlated with FEV1 in COPD, the ratio of SIgA/MUC5B was a better predictor of FEV1, particularly in patients with moderate COPD. Together, these findings suggest that SIgA production by submucosal glands, which are expanded in COPD, is insufficient to compensate for reduced SIgA transcytosis by airway epithelial cells. Localized SIgA deficiency on the surface of small airways is associated with COPD progression and represents a potential new therapeutic target in COPD.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, secretory IgA, submucosal glands, MUC5B, MUC5AC

Introduction

Each breath exposes the lungs to thousands of airborne antigens, pathogens, and smaller particles (<6 μm) which can be delivered to and deposited in distal airways [1, 2], rendering these areas susceptible to immunologic, infectious, or toxic injury, respectively. To protect the airways from these environmental challenges, the airway epithelium represents the first line of mucosal host defense. In addition to facilitating mucociliary clearance and producing antimicrobial peptides, airway epithelial cells participate in humoral immune host defense by transporting polymeric immunoglobulins (predominantly secretory IgA [SIgA]) to the mucosal surface via transcytosis [3-5].

These immunoglobulins serve as a core component of the adaptive humoral immune response. Structurally, SIgA consists of a secretory component (SC) and two or more IgA monomers joined by a J chain. IgA monomers and J chains are synthesized and assembled to polymeric IgA (pIgA) by subepithelial plasma cells, whereas SC is derived from polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) expressed in ciliated cells of bronchial epithelium or glandular cells of submucosal glands. Selective binding of the J chain to pIgR and subsequent transcytosis of pIgR-pIgA complexes across airway or submucosal glandular epithelia represent the basic mechanism of SIgA secretion [6-10]. After transport to the mucosal (airway) surface, pIgR is cleaved and the secretory component (SC) remains attached to IgA to form SIgA. SIgA supports mucosal host defense by immune exclusion and prevention of adherence or invasion of the airway mucosa by foreign antigens and microorganisms [11-14].

In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the airway epithelium is structurally and functionally abnormal and unable to maintain a normal mucosal immune barrier. In addition to impairment of mucociliary clearance mechanisms, airway epithelium in COPD is characterized by decreased expression of pIgR [15, 16], resulting in deficiency of SIgA on the mucosal surface of both large and small airways [16]. However, we have demonstrated that pIgR continues to be expressed in submucosal glands of COPD patients [16]. Although we showed that SIgA levels are reduced in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from patients with severe COPD [16], others have shown that SIgA levels in BAL from mild/moderate COPD are not reduced [17, 18] and both SC/pIgR and SIgA levels are paradoxically elevated in sputum from patients with COPD [19]. We hypothesized that the explanation for these apparently contradictory findings is that expansion of submucosal glands in COPD results in increased SIgA secretion by these glands; however, SIgA released from submucosal glands does not distribute on the airway surface to provide a normal immune barrier. Rather, SIgA from submucoals glands remains primarily within mucus clumps and plugs, leaving the airway surface unprotected. Thus, SIgA levels in the airway may remain within the normal range but the SIgA barrier is dysfunctional, even in mild and moderate COPD. To investigate this hypothesis, we measured SIgA levels on the airway surface and in the airway lumen by BAL and correlated these findings with mucus proteins (MUC5B and MUC5AC) produced preferentially in either mucosal glands or airways of COPD patients.

Methods

Lung Tissue Specimens

Lung tissue specimens were collected from lifelong non-smokers and former smokers with or without COPD. Tissue specimens from 30 lifelong non-smokers without known lung or cardiovascular diseases and 6 former smokers without COPD were obtained from donor lungs which were not used for lung transplantation. Tissue specimens from 10 former smokers without COPD and 22 patients with mild and moderate COPD (GOLD Stage I-II) were obtained from lungs resected for solitary tumors, whereas tissue specimens from 32 patients with severe and very severe COPD (GOLD Stage III-IV) were obtained from explanted lungs of transplant recipients. To standardize histological and morphometrical analyses, tissue specimens of large airways were obtained from segmental or subsegmental branches in each case. Lung parenchyma from the same region was then used to identify and analyze small airways. Only membranous airways with <2 mm in diameter were selected for analysis.

The severity of airflow obstruction was determined by FEV1 and FEV1/FVC measurements according to GOLD criteria [20, 21]. All individuals included in this study had abstained from smoking for > 1 year (Table 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University.

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants *.

| Lifelong non-smokers without COPD | Former Smokers without COPD | Patients with COPD by GOLD criteria (Former Smokers) [21] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| COPD I | COPD II | COPD III | COPD IV | |||

|

| ||||||

| Tissue samples | ||||||

| Number of study participants | 30 | 17 | 8 | 14 | 10 | 22 |

| Age (years) | 54.0 (17-74) | 57.0 (27-70) | 62.5 (59-74) | 67.0 (58-80) | 62.5 (49-71) | 55.0 (44-64) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 14 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| Female | 16 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 12 |

| Smoking history | ||||||

| Pack-year | – | 32.0 (9-88) | 47.5 (30-74) | 67.3 (20-100) | 50.0 (20-84) | 45.0 (30-80) |

| Smoke free (years) | – | 10.0 (2-23) | 4.5 (2-9) | 8.0 (2-25) | 4.5 (3-21) | 3.5 (1-15) |

| FEV1 (% of predicted)** | – | 97.5 (86-121) | 86.5 (81-95) | 64.5 (53-72) | 35.5 (30-48) | 21.0 (16-28) |

| FEV1 / FVC (% of FVC)** | – | 79.3 (75-83) | 66.3 (58-69) | 55.1 (40-66) | 38.9 (32-53) | 29.6 (21-57) |

|

| ||||||

| BAL samples | ||||||

| Number of study participants | – | 26 | 23 | 24 | 6 | 1 |

| Age (years) | – | 63.5 (57-72) | 64.0 (57-74) | 65.0 (57-74) | 63.0 (60-71) | 60 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | – | 13 | 16 | 15 | 5 | 1 |

| Female | – | 13 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| Smoking history | ||||||

| Pack-year | – | 40.0 (37.5-94) | 52.0 (35-115) | 58.5 (24-126) | 49.0 (40-94) | 108 |

| Smoke free (years) | – | 14.0 (2-35) | 14.0 (1-25) | 11.5 (1-24) | 6.5 (2-11) | 10 |

| FEV1 (% of predicted) | – | 95.5 (82-114) | 89.0 (81-109) | 68.0 (52-79) | 41.5 (33-48) | 24 |

| FEV1 / FVC (% of FVC) | – | 76.0 (72-85) | 66.0 (59-69) | 63.0 (51-69) | 43.5 (42-62) | 37 |

Median and range () are indicated for each parameter.

FEV1 and FVC were not available in lifelong non-smoking donors and were available in 10 from 17 former smokers without COPD. These parameters were available in all former smokers with COPD.

FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC – forced vital capacity.

Airway Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (5 μm) were cut from each tissue block. Two serial sections from each tissue block were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for routine histologic evaluation or the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction for detection of mucus. Double immunofluorescent immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed using two different pairs of primary antibodies – IgA and pIgR or MUC5AC and MUC5B. Primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal for IgA (A0262, DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and MUC5B (ABIN739920, Antibodies-online, Atlanta, GA) or murine monoclonal for pIgR (clone SC-05, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) and MUC5AC (clone CLH2, MAB2011, EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies were labeled with FITC or Cy3, respectively (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory). The murine monoclonal anti-pIgR antibody demonstrated consistent staining on the basolateral surfaces rather than the apical surfaces of ciliated epithelial cells, suggesting that the antibody binds only pIgR, and not the SC of SIgA molecules. The specificity of IHC was verified using an antibody isotype control replacing the primary antiserum with an identical concentration of non-immunized mouse or rabbit serum (Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA).

Histomorphometry

Areas of bronchial mucosa involved by goblet cell hyperplasia were determined by measuring the total circumference of the basement membrane and the length of basement membrane subjacent to epithelium with goblet cell hyperplasia on consecutive non-overlapping images of bronchial mucosa. To determine submucosal gland volume density in large airways, the area of each individual submucosal gland was measured. Total glandular area (VVglands) was summed and then divided by the length of the reticular basement membrane (RBM).

In small airways, IgA quantification was performed by measurement of IgA-specific fluorescent signal. One tissue section from each block was immunostained with primary antibodies against IgA using fluorescent labeling (FITC). Digital images of individual small airways (less than 2 mm diameter) were captured with the same magnification (×10 objective) and the same digital camera settings. Intensity of IgA-specific fluorescent signal was measured in 8 spots equally spaced along the circumference of the epithelial surface (by 45° angle). Intensity of fluorescent signal was measured in actual pixel value (apv) using the Line Profile to obtain a plot of actual intensity values of a single perpendicular line crossing the mucosal layer localized on epithelial surface. Average intensity was calculated for each individual airway and each study participant.

Percent of airways containing luminal mucus plugs was also calculated. 1514 small airways were analyzed, including 449 airways in lifelong non-smokers, 275 airways in former smokers without COPD, 296 airways in former smokers with mild and moderate COPD, and 492 airways in former smokers with severe and very severe COPD.

Immunofluorescent images were captured using an Olympus IX81 Inverted Microscope with Spinning Disc Confocal Configuration (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Images of large and small airways were captured using Olympus microscope and DP71 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). All morphometric measurements were made by calibrated image analysis with standard Image-Pro Express software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD).

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Samples

BAL fluids were obtained from 26 former smokers without COPD and 54 former smokers with stable COPD (not having an acute exacerbation) (Table 1). BAL fluid was recovered using 150 ml (3×50 ml) normal saline lavage with the bronchoscope wedged in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe. The second and third returns were collected as small airway and alveolar lavage, and then used in this study. Collected fluids were centrifuged at 300×g for 10 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was immediately frozen at -80°C. SIgA and MUC5B concentrations were measured using specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA).

For quantification of SIgA, we used rabbit polyclonal anti-IgA antibody (1:1000, #A0262, DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) as coating antibody and goat polyclonal anti-SC/pIgR antibody (1:5000, #AF2717, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as detecting antibody. 10 μl of each BAL sample was diluted five-fold with bicarbonate-carbonate buffer, placed in triplicate in 384-well plate and incubated for 2 hours. HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat polyclonal antibody (1:5000, #PA1-28664, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used for detection. Pooled normal human colostrum SIgA was used for calibration (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA).

To measure MUC5B concentration, 10 μl of each BAL sample was diluted four-fold with bicarbonate-carbonate buffer, placed in triplicate in 384-well plate and then incubated overnight at 4°C. To detect MUC5B, mouse polyclonal anti-MUC5B antibody (1:1000, #H00727897-A01, Abnova, Walnut, CA) was used. Then, the plate was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:5000, #31462, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Human MUC5B recombinant protein (#H00727897-Q01, Abnova) was used for calibration. Because we used non-glycosylated recombinant protein as a standard, relatively low level of MUC5B was detected by using this assay.

Color reaction was performed with developing TMB substrate solution (Clinical Science Products, Mansfield, MA) and terminated with 1M H2SO4 stop solution. All procedures were performed at room temperature. Absorbance was read at 450 nm.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as medians and inter-quartile range. A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied for comparisons between study groups. Correlations were assessed using a Spearman test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant in two-tailed hypothesis tests.

Results

Total luminal content of SIgA does not correlate with airway surface SIgA deficiency in COPD

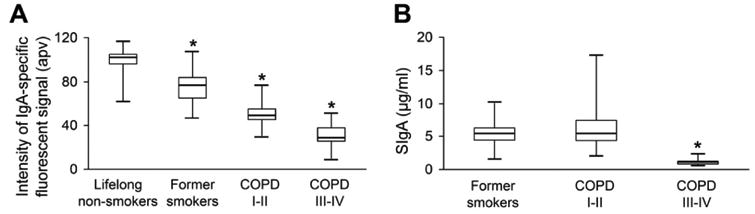

Similar to our previous report [16], we found that IgA-specific fluorescence intensity on the epithelial (mucosal) surface of small airways showed reduction of SIgA in patients with COPD compared to control subjects (Figure 1A; p < 0.01). However, levels of SIgA in BAL samples from patients with mild/moderate COPD were not significantly different from former smokers without COPD, while patients with severe COPD showed reduced BAL SIgA concentration (Figure 1B; p < 0.01). Together, these data point to a discrepancy between airway SIgA concentration measured in BAL compared with the SIgA barrier present on the airway surface.

Figure 1.

Measurements of SIgA levels from different clinical specimens. A – boxplot showing -specific fluorescent signal on the epithelial surfaces of small airways from lifelong non-smokers and former smokers without COPD, and patients with mild-moderate (GOLD Stage I-II) or severe-very severe (GOLD Stage III-IV) COPD. * – p < 0.01 compared to lifelong non-smokers. B – boxplot showing reduced SIgA concentrations in BAL fluids obtained from severe-very severe COPD (GOLD Stage III-IV) compared to former smokers without COPD and COPD patients with mild-to-moderate disease severity (GOLD stage I-II). * – p < 0.01 compared to former smokers without COPD and former smokers with mild-moderate COPD.

SIgA secretion in submucosal glands does not compensate its surface deficiency in airways

Evaluation of large airways showed goblet cell hyperplasia and enlargement of submucosal glands in patients with COPD compared to non-diseased control subjects (Figure 2). We defined goblet cell hyperplasia as the ratio of goblet cells to total airway surface epithelial cells ≥1:2 (this ratio typically varies from 1:8 to 1:20 in normal airways [22-24]. In contrast to the progressive increase in goblet cell hyperplasia with disease severity, enlargement of submucosal glands was similar in patients with mild-moderate and severe COPD (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Histological assessment of mucus-producing elements in large airways. A, B – representative images showing segments of large airways from lifelong non-smoker (A) and a patient with severe (GOLD stage III) COPD (B). Extensive goblet cell hyperplasia of airway surface epithelium and enlargement of submucosal glands are seen a patient with severe (GOLD stage III) COPD (PAS-stained tissue sections, ×100). C – graph showing degree of goblet cell hyperplasia of surface airway epithelium in different clinical groups. D – graph showing increased volume of submucosal glands in COPD patients compared to lifelong non-smokers and former smokers (VVglands – gland volume density, measured as the total area of submucosal glands normalized to length of basement membrane). Mean ± SD is indicated for each epithelial subtype. * – p < 0.01 compared to lifelong non-smokers and former smokers without COPD.

Next, we performed IHC analysis of serial tissue sections for IgA, pIgR, MUC5AC and MUC5B. In both lifelong non-smokers and former smokers without COPD, we observed expression of pIgR along the basolateral surfaces of ciliated epithelial cells and the presence of IgA on the mucosal surface, indicative of an intact SIgA immune barrier. Expression of pIgR was also detected in glandular epithelial cells of serous acini of submucosal glands. Most goblet cells of the airway epithelium were positive for MUC5AC, with fewer goblet cells positive for MUC5B or both mucins. In submucosal glands, mucous acini contained mainly MUC5B positive cells (Figure 3A). In contrast, goblet cells on the airway surface of COPD patients expressed only MUC5AC, whereas mucous acini of submucosal glands exclusively expressed MUC5B (Figure 3B). While pIgR expression by airway epithelial cells and surface SIgA levels were markedly reduced, pIgR expression was preserved in serous glandular cells and IgA was detectable in MUC5B-positive mucus within collecting ducts. Luminal mucus in large airways was positive for MUC5B (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Relationship of mucus dysfunction and surface SIgA deficiency in large airways in COPD. A – panel showing airway surface epithelium (top row) and submucosal gland (bottom row) from a lifelong non-smoker. Normal-appearing, pseudo-stratified epithelium shows expression of pIgR on basolateral surface of ciliated cells (insert, red) and SIgA on the mucosal surface (green); goblet cells are positive for MUC5AC, MUC5B, or both mucins. Expression of pIgR in serous acini and predominant production of MUC5B in submucosal glands is also demonstrated. B – panel showing airway surface epithelium (top row) and submucosal gland (bottom row) from a patient with severe (GOLD stage III) COPD. Down-regulation of pIgR expression in airway epithelial cells (insert, red) is associated with reduced SIgA expression on the mucosal surface (green). Goblet cells of surface airway epithelium are positive for MUC5AC, but not for MUC5B. Both SIgA and MUC5B, but not MUC5AC, are detected in luminal mucus plugs. Expression of pIgR is retained in some serous acini of submucosal glands, whereas MUC5B is the predominant mucin expressed in mucus acini of submucosal glands. Note collecting ducts (D) filled with IgA and MUC5B-positive secretions. Left column – PAS-stained tissue sections; middle column – double immunostain with primary antibodies against IgA (green) and pIgR (red); right column – double immunostain with primary antibodies against MUC5B (green) and MUC5AC (red). Confocal microscope images, ×100; inserts, ×400.

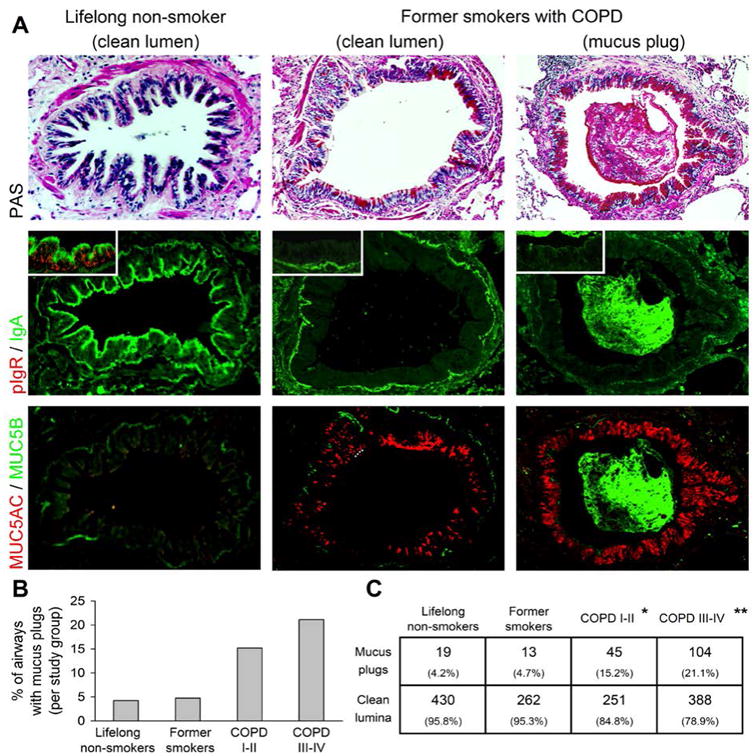

As shown in Figure 4A, most small airways from lifelong non-smokers were characterized by widespread pIgR expression in airway epithelial cells and IgA accumulation on the epithelial surface. Similar findings were present in former smokers without COPD (data not shown). In contrast, small airways from patients with COPD were characterized by goblet cell metaplasia and SIgA deficiency on the mucosal surface. While SIgA was reduced on the surface of small airways in COPD patients, SIgA was present in mucus plugs within these airways and the percentage of small airways containing mucus plugs increased with disease severity (Figure 4BC; p < 0.05). Analysis of mucins in airway plugs showed the exclusive presence of MUC5B as well as SIgA (Figure 4A, right panels); however, MUC5AC was expressed by epithelial goblet cells. Together, these data demonstrate that luminal mucus plugs in COPD likely originate from submucosal glands and SIgA secreted from submucosal glands remains sequestered within these mucus plugs.

Figure 4.

Relationship of mucus dysfunction and surface SIgA deficiency in small airways in COPD. A – images of serial sections of small airways from a lifelong non-smoker (left column) show strong pIgR expression in epithelial cells (inset) and SIgA on the mucosal surface; MUC5AC and MUC5B are non-detectable in the normal-appearing surface epithelium. The middle and right columns are representative of small airways without (middle) or with (right) associated mucus plugs from a patient with severe (GOLD stage III) COPD. pIgR expression is absent in surface epithelial cells and SIgA undetectable on the mucosal surface. There is expression of MUC5AC, but not MUC5B, in goblet cells of lining epithelium. Mucus plugs contain abundant IgA and MUC5B. B – progressive increase in the percentage of small airways containing mucus plugs in different clinical groups. C – table showing numbers and percentages of airways containing luminal mucus plugs. p < 0.05 compared to lifelong non-smokers; p < 0.05 compared to all other groups by Chi-square test.

Relationship of bronchial mucosal SIgA deficiency with mucus dysfunction in COPD

Measurements of SIgA in different clinical samples (tissue sections vs. BAL fluid) showed that airway surface SIgA deficiency in patients with mild and moderate COPD was not associated with significant changes in total luminal SIgA levels. Scatterplots of SIgA concentrations in BAL samples and FEV1 show that despite a significant positive correlation coefficient (r = 0.519, p < 0.001), some patients with moderate COPD had unexpectedly high SIgA levels (Figure 5A). We measured MUC5B in BAL samples and documented progressive elevation with increasing disease severity (Figure 5B; p < 0.05). To explain the outliers with SIgA elevation out of proportion to FEV1, we analyzed MUC5B concentration in BAL from the moderately severe COPD patient group and found a significant elevation of MUC5B in the 8 patients with high SIgA levels (Figure 5C; p < 0.01). Based on these observations, we propose that elevation of luminal SIgA in these patients results from increased delivery of submucosal gland secretions. Therefore, we calculated an SIgA/MUC5B index and related this parameter to FEV1. Compared to SIgA levels alone, we identified improved correlation between these parameters (Figure 5D; r = 0.519 vs. r = 0.674).

Figure 5.

Relationship of MUC5B and SIgA in COPD. A – scatterplot showing significant correlation between SIgA concentration in BAL fluids and FEV1. Eight patients with moderate COPD (GOLD stage II) had elevated SIgA levels and appear to be outliers from the regression line (open diamonds). B – boxplots showing increased concentrations of MUC5B in BAL fluids from patients with COPD (GOLD stages I-IV) compared to former smokers without COPD. * – p < 0.05 compared to former smokers without COPD. C – boxplot showing increased levels of MUC5B in patients with moderate COPD (GOLD stage II) with high BAL SIgA levels compared to other COPD patients with low SIgA levels. * – p < 0.01 compared to both other groups. D – scatterplot showing significant correlation between SIgA/MUC5B ratio in BAL fluid and FEV1.

Discussion

Our results provide new information about the nature of bronchial mucosal SIgA deficiency in COPD. While pIgR-mediated transcytosis across airway surface epithelium was reduced, we demonstrated that SIgA secretion from tracheobronchial submucosal glands is intact. However, SIgA from submucosal glands is unable to compensate for the airway surface deficiency. Airway luminal mucus aggregates and mucus plugs in small airways appear to originate from tracheobronchial submucosal glands of more proximal airways and SIgA secreted from submucosal glands remains trapped within luminal mucus plugs. SIgA in mucus plugs fails to distribute along the airway mucosal surface and therefore does not result in an intact airway SIgA barrier in COPD.

The airway epithelium generates the first line of mucosal host defense by facilitating mucociliary clearance, producing antimicrobial peptides and proteins, and transporting immunoglobulins to the airway surface [3-5]. In normal conditions, inhaled particulates and microorganisms are trapped in surface mucus, agglutinated by specific SIgA, and then removed via mucociliary escalator. In this study, we focused on SIgA due to its high specificity to antigens and its unique function which cannot be compensated by other host defense components. Here we demonstrated a link between airway mucus dysfunction and surface SIgA deficiency. Optimal production and effective clearance of mucus are essential for lung health, whereas mucus dysfunction occurs in virtually all inflammatory lung diseases [25, 26]. Increased mucus production in COPD has deleterious consequences for airway health, including mucus plugging and infection [24, 26]. Whereas healthy mucus is a gel with low viscosity and elasticity, pathologic mucus in COPD loses these properties due to increased solid content, up to 15% in COPD compared to 3% in normal [24, 25]. We speculate that the disproportionate increase of mucous acini in submucosal glands [27, 28] and dehydration of airway mucosa [29-31] are additional factors predisposing to mucus dysfunction in COPD. As a result, mucus secreted from submucosal glands in COPD forms sticky plugs and does not distribute on the epithelial surfaces of airways. We further speculate that widespread epithelial remodeling [27, 32] and malfunction of the ciliary clearance apparatus [33, 34] are also responsible for mucus stasis and ineffective mucus plug removal from airways in patients with COPD. Our finding that the number of small airways with mucus plugs increases with disease severity suggests a direct link between mucus plugging and airflow limitation in patients with COPD.

Mucus dysfunction in COPD affects the function of the SIgA immune system. This conclusion is based on the histological findings of MUC5B expression exclusively in submucosal glands and co-localization of IgA and MUC5B within the collecting ducts of submucosal glands and mucus plugs within airway lumina. We suggest that SIgA secreted from submucosal glands remains trapped within luminal mucus plugs, does not distribute properly on bronchial mucosal surface, and does not compensate for deficient surface SIgA resulting from limited transcytosis across airway epithelium. These findings would also explain the apparent discrepancy between measurements of SIgA levels in different clinical samples (tissue specimens vs. BAL). In mild and moderate COPD, SIgA secreted by submucosal glands increases total luminal SIgA content and is detectable within BAL fluid, masking the presence of surface SIgA deficiency in small airways. In severe COPD, with more profound surface SIgA deficiency, the total luminal content of SIgA decreases such that it is also reduced in BAL fluid.

Since small airborne particles (<6 μm) can be delivered to the transitional region of small airways and deposited there [1, 2], the functional status of mucosal host defense mechanisms plays a critical role in the protection against these antigenic challenges. Chronic bombardment of defenseless epithelium in COPD by inhaled antigens and pathogens can damage airway epithelial cells and lead to activation of pro-inflammatory signaling and release of pro-inflammatory mediators, thus promoting airway inflammation [35, 36]. Correlations of SIgA deficiency on the surface of small airways with immune/inflammatory cell accumulation, airway wall fibrous remodeling and airflow limitation in COPD [16] support our concept that surface SIgA deficiency in COPD seriously compromises mucosal host defense mechanisms and might be responsible for persistent inflammation and remodeling in susceptible humans even after smoking cessation. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which the airway epithelium maintains an effective immunobarrier could lead to development of new therapeutic strategies for COPD targeting mucus overproduction, impaired mucociliary clearance, and abnormal immune-barrier function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH NHLBI HL092870, HL085317, HL105479, T32 HL094296, NIH HL088263, NIH HL126176, NIH NCRR UL1 RR024975, NCI U01 CA152662), the Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award 1l01BX002378, and Forest Research Institute grant (DAL-IT-07).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Peterson JB, Prisk GK, Darquenne C. Aerosol deposition in the human lung periphery is increased by reduced-density gas breathing. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2008;21:159–168. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2007.0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darquenne C. Aerosol deposition in health and disease. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2012;25:140–147. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2011.0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilette C, Ouadrhiri Y, Godding V, et al. Lung mucosal immunity: immunoglobulin-A revisited. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:571–588. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00228801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight DA, Holgate ST. The airway epithelium: structural and functional properties in health and disease. Respirology. 2003;8:432–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilette C, Durham SR, Vaerman JP, et al. Mucosal immunity in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a role for immunoglobulin A? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:125–135. doi: 10.1513/pats.2306032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman MR, Link DW, Brown WR, et al. Ultrastructural evidence of transport of secretory IgA across bronchial epithelium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123:115–119. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haimoto H, Nagura H, Imaizumi M, et al. Immunoelectronmicroscopic study on the transport of secretory IgA in the lower respiratory tract and alveoli. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404:369–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00695221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunziker W, Kraehenbuhl JP. Epithelial transcytosis of immunoglobulins. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1998;3:287–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1018715511178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen FE, Braathen R, Brandtzaeg P. The J chain is essential for polymeric Ig receptor-mediated epithelial transport of IgA. J Immunol. 2001;167:5185–5192. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandtzaeg P, Johansen FE. Mucosal B cells: phenotypic characteristics, transcriptional regulation, and homing properties. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:32–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandtzaeg P. Role of secretory antibodies in the defence against infections. Int J Med Microbiol. 2003;293:3–15. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woof JM, Kerr MA. The function of immunoglobulin A in immunity. J Pathol. 2006;208:270–282. doi: 10.1002/path.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandtzaeg P. Induction of secretory immunity and memory at mucosal surfaces. Vaccine. 2007;25:5467–5484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corthesy B. Roundtrip ticket for secretory IgA: role in mucosal homeostasis? J Immunol. 2007;178:27–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilette C, Godding V, Kiss R, et al. Reduced epithelial expression of secretory component in small airways correlates with airflow obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:185–194. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.9912137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polosukhin VV, Cates JM, Lawson WE, et al. Bronchial secretory immunoglobulin A deficiency correlates with airway inflammation and progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:317–327. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1629OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockley RA, Burnett D. Local IgA production in patients with chronic bronchitis: effect of acute respiratory infection. Thorax. 1980;35:202–206. doi: 10.1136/thx.35.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atis S, Tutluoglu B, Salepci B, et al. Serum IgA and secretory IgA levels in bronchial lavages from patients with a variety of respiratory diseases. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2001;11:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohlmeier S, Mazur W, Linja-Aho A, et al. Sputum proteomics identifies elevated PIGR levels in smokers and mild-to-moderate COPD. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:599–608. doi: 10.1021/pr2006395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–1276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Revised 2014. [Accessed on January 23, 2014];Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2014 Available online: www.goldcopd.org.

- 22.Davis CW, Dickey BF. Regulated airway goblet cell mucin secretion. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:487–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boucherat O, Boczkowski J, Jeannotte L, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of goblet cell metaplasia in the respiratory airways. Exp Lung Res. 2013;39:207–216. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2013.791733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos FL, Krahnke JS, Kim V. Clinical issues of mucus accumulation in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:139–150. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S38938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voynow JA, Rubin BK. Mucins, mucus, and sputum. Chest. 2009;135:505–512. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fahy JV, Dickey BF. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2233–2247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeffery PK. Remodeling in asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:S28–S38. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.supplement_2.2106061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maestrelli P, Saetta M, Mapp CE, et al. Remodeling in response to infection and injury. Airway inflammation and hypersecretion of mucus in smoking subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:S76–S80. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.supplement_2.2106067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clunes LA, Davies CM, Coakley RD, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure induces CFTR internalization and insolubility, leading to airway surface liquid dehydration. FASEB J. 2012;26:533–545. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-192377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh A, Boucher RC, Tarran R. Airway hydration and COPD. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1946-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seys LJ, Verhamme FM, Dupont LL, et al. Airway Surface Dehydration Aggravates Cigarette Smoke-Induced Hallmarks of COPD in Mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polosukhin VV. Ultrastructure of the bronchial epithelium in chronic inflammation. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2001;25:119–128. doi: 10.1080/01913120120916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wanner A. The role of mucus in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1990;97:11S–15S. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.2_supplement.11s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganesan S, Comstock AT, Sajjan US. Barrier function of airway tract epithelium. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1:e24997. doi: 10.4161/tisb.24997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hallstrand TS, Hackett TL, Altemeier WA, et al. Airway epithelial regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2014;151:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holtzman MJ, Byers DE, Alexander-Brett J, et al. The role of airway epithelial cells and innate immune cells in chronic respiratory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:686–698. doi: 10.1038/nri3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]