Abstract

The ascendance of the autonomy paradigm in treatment decision‐making has evolved over the past several decades to the point where few bioethicists would question that it is the guiding value driving health‐care provider behaviour. In achieving quasi‐legal status, decision‐making has come to be regarded as a formality largely removed from the broader context of medical communication and the therapeutic relationship within which care is delivered. Moreover, disregard for individual patient preference, resistance, reluctance, or incompetence has at times produced pro forma and useless autonomy rituals. Failures of this kind, have been largely attributed to the psychological dynamics of the patients, physicians, illnesses, and contexts that characterize the medical decision. There has been little attempt to provide a framework for accommodating or understanding the larger social context and social influences that contribute to this variation. Applying Paulo Freire’s participatory social orientation model to the context of the medical visit suggests a framework for viewing the impact of physicians’ communication behaviours on patients’ capacity for treatment decision‐making. Physicians’ use of communication strategies can act to reinforce an experience of patient dependence or self‐reliance in regard to the patient‐physician relationship generally and treatment decision‐making, in particular. Certain communications enhance patient participation in the medical visit’s dialogue, contribute to patient engagement in problem posing and problem‐solving, and finally, facilitate patient confidence and competence to undertake autonomous action. The purpose of this essay is to place treatment decision‐making within the broader context of the therapeutic relationship, and to describe ways in which routine medical visit communication can accommodate individual patient preferences and help develop and further patient capacity for autonomous decision‐making.

Keywords: doctor‐patient communication, doctor‐patient relationship, medical visits, treatment decision‐making

Introduction

Whilst medicine is recognized as serving patients’ needs, even above self‐interest and gain, it has traditionally relied on the judgement of physicians to define those needs. 1 Many, however, would argue that physicians’ judgement is neither a sufficient nor adequate basis for the definition of patient need. Even the very earliest medical writings have linked patient autonomy and physicians actions. In distinguishing between the actions of physicians to slaves and a freemen, Plato views the defining element to be imposition of treatment versus education and dialogue:

A physician to slaves never gives his patient any account of his illness…the physician offers some orders gleaned from experience with an air of infallible knowledge, in the brusque fashion of a dictator… The free physician, who usually cares for free men, treats their diseases first by thoroughly discussing with the patient and his friends his ailment. This way he learns something from the sufferer and simultaneously instructs him. 2

In anticipating our current attachment to the principles of autonomy and self‐determination, Plato’s admonition to learn something from the sufferer has been transformed such that a patient ought/should/must provide the physician with a definition of medical need for themselves. Ascendance of the autonomy paradigm has evolved over the past several decades to the point where few bioethicists would question that it is the guiding value driving health‐care provider behaviour. 3 Indeed, it has been argued that patient autonomy has achieved paradigmatic status superseding principles of beneficence and social justice in bioethics and medical law. 4

The formalization of decision‐making as a discrete act with legal standing has had the effect of setting these exchanges apart from the larger context of communication and the therapeutic relationship within which care is delivered. Thus, decision‐making has come to be regarded as a dichotomous outcome – either present or not present, rather than an ‘in‐context’ dynamic process reflecting the richness and depth that defines the therapeutic relationship.

The purpose of this essay is to place treatment decision‐making within the broader context of the therapeutic relationship, and to describe ways in which routine medical visit communication can accommodate individual patient preferences and help develop and further patient capacity for autonomous decision‐making.

Treatment decision‐making and the autonomy paradigm

Legal support for the doctrine of patient autonomy originated as a largely protective principle designed to inoculate patients against the possible transformation of legitimate medical authority to medical paternalism. 4 , 5 Within this context, the most fully discussed area of contention is in regard to access and ownership of medical information, as it relates to medical and treatment decision‐making and informed consent.

The traditional sociological debates proffer two views: the first is one of consensual accommodation and the second is outright conflict. The consensual view has been articulated by Talcott Parsons 6 who argued that conflict between physician and patient is diffused by well‐defined societal expectations for role performance; both doctors and patients have their job to do. In contrast, Freidson 7 sees conflict over information as fundamental to the very nature of the doctor‐patient relationship. Parsons argues that inherent in the definition of a physician is the dedication of a lifetime to mastery of knowledge and the gaining of experience in the application of that knowledge. The fund of medical knowledge is so vast and complex, the schooling so intense and gruelling, and the daily experience so unique, that an unbridgeable competence gap exists between physicians and the lay world. Moreover, the knowledge is learned and transmitted only in the encrypted foreign code of medical jargon. Thus, medical knowledge is earned and owned by doctors and impossible to share, at least not in any meaningful manner with the lay person. There are protections afforded patients since they must accept medical practice on faith. Central to this protection is a higher order of moral conduct that physicians are held to, including a code of ethics defining the special duty of physicians to protect the interests of their patients. Patients, for their part, rely on physician adherence to this moral code and therefore trust that they will be given what information they need, if not all that they want.

In contrast, Freidson views information exchange in terms of rights and obligations; patients have the right to information and physicians have the obligation to convey it in an understandable and useful manner. 7 Freidson sees the disinclination of physicians to share information with patients less as a function of an irreducible competence gap than as a safeguard for high status and professional standing. A less knowledgeable patient is less likely to contest medical conduct, second‐guess medical decisions, or detect medical errors. 7

Agreeing fundamentally with Freidson, others have elaborated the conflict between the physician and patient to reside not only in the control of information but in a paradigmatic conflict of perspectives and language. 8 , 9, 10, –11 Depending on the resolution of this conflict, the patient’s problem will be anchored in either medicine’s biomedical and disease context or the broader and more integrated context of the patient’s illness experience. Based on this anchor, the visit’s agenda and therapeutic course will be set and the foundation for treatment decision‐making will be established.

The vehicle through which the competition over paradigms and perspectives takes place is the medical dialogue. The boundaries of autonomy and paternalism are negotiated through the determination of how much information, with what level of detail, given when, under what circumstances, in whose language, and in what context. As a result of the great variability in patients’ ability to negotiate the medical dialogue, ethicists have identified protection from verbal coercion with almost universal regard as a necessary and important element of civilized and enlightened medical care. 11

Is the autonomy paradigm illusory?

That the protections against medical paternalism have achieved some success is evident in such pronouncements of victory as those made by Arthur Caplan:

The Freddy Kruger of bioethics for the better part of two decades has been the doctor who pushes his or her values onto the patient… This devil has been completely exorcised and a large part of contemporary bioethics scholarship seems to be devoted to the task of assuring that the paternalistic doctor stays dead and buried… 3 (p. 259).

This victory, however, may only be illusory; whilst the letter of the law has produced the appearance of protection against paternalism, the spirit has often been neglected. More often than recognized by either bioethicists or the law, disregard for individual patient preference, resistance, reluctance, or incompetence has resulted in pro forma and useless autonomy rituals. 4

The failure of the autonomy principle in practice has been attributed to a growing depersonalization of the doctor‐patient relationship, exacerbated within the context of increasingly technological and bureaucratic care. 4 , 12 , 13 Ironically, the legal protections designed to encourage and support open communication have often acted as a constraint. As argued by Schneider:

Rights exacerbate the impersonality of the relations between doctor and patient…and the process is self‐reinforcing: trust wanes as relationships become more bureaucratic and less personal. This creates a call for rights. The rights solution further alienates doctor and patient because it distances them and because the doctor resents the distrust that motivated the solution 4 (p. 201).

Although patients want information from their physicians, information is not all that they want. Physicians are not simply expert consultants, although they are that; they are also someone to whom people go when they are particularly vulnerable. 6 There are some patients, and perhaps many patients at especially vulnerable junctures and in particular circumstances, that do not want to or cannot assume the burden for their medical decisions. 4

Individual variation in preferences and capacity along the autonomy continuum have been largely attributed to the psychological dynamics of the patients, physicians, illnesses, and contexts that characterize the medical decision. 4 There has been little attempt to provide a framework for accommodating or understanding the larger social context and social influences that contribute to this variation.

The work of Paulo Freire may be helpful in this regard. 14 Whilst originally applied to the teaching of basic literacy skills to adults, and more widely used in the area of community development and health education, 15 Freire sees the economic, political, and social relations that often characterize vulnerable populations as mirrored in their educational experiences. Traditional approaches to teaching in which learners are treated as passive and dependent objects act to reinforce powerlessness and helplessness. In contrast, participatory learning strategies that treat people as active subjects of their own learning can have the effect of changing patterns of dependence and passivity by providing and reinforcing empowering experiences.

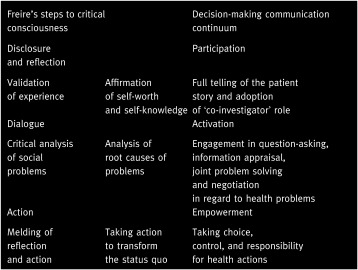

Empowering experiences foster the competence and confidence necessary for personal transformation and the realization of ‘critical consciousness’. This transformation is attributed to three key consciousness raising experiences: relating and reflecting on experience, engaging in dialogue, and taking conscious action. These steps provide a framework for Freire’s participatory social orientation approach to the design of effective educational strategies. As illustrated in Fig. 1(a) parallel approach reflecting a participatory social orientation to treatment decision‐making maps the experience of patients to those steps delineated by Freire. The areas of overlap are highlighted in the central boxes of the figure; key Freirian consciousness raising experiences are listed on the left and key aspects of the medical dialogue are on the right.

Figure 1.

Participatory social orientation approach to treatment decision‐making.

Applying these ideas to the social context of the medical visit, implications for the impact of physicians’ communication behaviours on patients’ capacity for treatment decision‐making can be drawn. As is the case for educators, the use of particular communication strategies act to reinforce an experience of dependence or self‐reliance. Some communication strategies enhance patient participation in the medical visit’s dialogue, contribute to patient engagement in problem posing and problem‐solving, and finally, facilitate patient confidence and competence to undertake autonomous action.

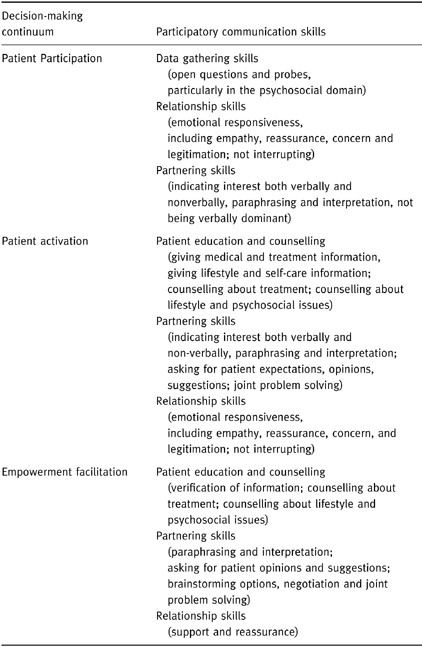

Table 1 identifies participatory physician communication skills likely to enhance autonomy in decision‐making by enabling patient experience of participation, activation, and empowerment. (For illustrative purposes, the Appendix presents examples of medical dialogue drawn from studies using the Roter Interaction Analysis System [RIAS] 16 ).

Table 1.

Physicians’ participatory communication skills related to the facilitation of patient autonomy in medical decision‐making

Participation continuum

Relating and reflecting life experiences with all of their emotional and social significance carries a force that Freire found to be critical in building confidence at the most fundamental level in which the self is expressed. A similar sentiment has been expressed by George Engel in recognizing the power for the patient in telling his/her story:

…interpersonal engagement required in the clinical realm rests on complementary and basic human needs, especially the need to know and understand and the need to feel known and understood 17 (p. 124).

In affirming the worth and relevance of life‐experience, self‐reflection is encouraged and the patient is transformed from a reporter of symptoms to a ‘coinvestigator’ of his/her health problems. 15 The issues uncovered in self‐reflection may then constitute the agenda of the medical visit.

The critical communication skills that facilitate active patient participation in the medical visit include those originally derived from the psychotherapy literature and applied to interviewing skills: data gathering, relationship‐building, and partnering skills. 18 At its most elementary level, patient participation in the medical visit can be seen as reactive; physicians inquire and patients respond. Data gathering skills reflect a variety of questioning behaviours that encompass variation in both form and content. Restricted opportunities for patient participation in the visit are provided through closed‐ended questions to which the patient provides direct answers. The transformation from restricted to full participation is contingent on broadening the parameters of elicitation so that patients can fully and most meaningfully tell their story. Open questions by their very nature allow more room for patient discretion in response than closed‐ended questions. Questions about things patients know and care about and that are relevant to daily experience and context will enhance the parameters and meaning of disclosure.

Relationship‐building skills, include emotional support, empathy, reassurance, and personal regard create an atmosphere that facilitates open and sensitive disclosure by optimizing rapport and trust. Partnership skills also make it easier for a patient to tell their story by actively facilitating patient input through prompts and signals of interest, interpretations, paraphrase, requests for opinion and probes for understanding. In addition, patients may be encouraged to more actively participate in the visit by having the physician assume a less dominating relationship stance. This includes lowered verbal dominance by listening more and talking less, using head nods and eye contact and forward body lean to signal interest.

Activation continuum

The second Frierian step is ‘dialogue’. This raises the level of active engagement from disclosure to critical analysis and includes a process that encourages examination of one’s situation and the core conditions and circumstances that have contributed to it. As applied to health, the medical dialogue provides the vehicle of patient activation in agenda setting, information‐seeking, reflection, problem‐posing and joint problem‐solving.

Active involvement in the dialogue transforms the patient role from reactive to proactive with patients taking the initiative in assuring that their agenda is presented and their needs met. Activation interventions have generally included guides or algorithms to help patients identify, phrase, and rehearse questions, concerns, and issues to be included in the agenda of the visit. 19 , 20 Physicians can assist patients by providing full and relevant information and counselling, by the use of partnership‐building skills, including the solicitation of patient questions, expectations, preferences, probing the patient’s explanatory framework, and by engaging in a process of negotiation and problem solving related to treatment and lifestyle regimens. A particularly important partnership‐building behaviour is simply not to interrupt. A frequently cited study by Beckman and colleagues found that patients were interrupted after an average of 18 seconds with follow‐up of the first but not necessarily most important stated concern. 21

Empowerment continuum

The third and final step to autonomy in the Freirian process transforms the dialogue of problem posing and problem solving to recognition of one’s ability to control and transform life circumstances through action. Patient empowerment implies the ability to assume control and responsibility for one’s health and health related actions.

Whilst medicine has long recognized the importance of patient responsibility for health behaviours, there has been relatively little attention to the extent to which physicians may facilitate this process. A contribution in this regard has been made by the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS). 22 This study surveyed over 7000 patients after visits with 300 physicians to determine the extent to which the patients report having been offered choice, control, and responsibility over treatment decisions. Physician practices and patient experience in terms of shared decision‐making was found to vary widely. Most notably, physicians with primary care or interviewing skills training were reported to be more facilitative of active patient engagement in the decision‐making process than were other physicians.

Whilst the MOS study did not identify particular facilitative skills for participatory decision‐making, other observational studies have found that physicians trained in interviewing skills differed from other physicians in key ways: trained physicians were more likely to engage in discussion of psychosocial issues, be emotionally supportive, ask questions in an open manner, ask for patient opinion, be skilled in interpersonal communication, be psychologically minded, and be less verbally dominant. 23 , 24, –25 These skills are likely to extend the influence of the therapeutic relationship to the building of patient confidence and competence to act on one’s own behalf. 26 In using these skills for empowerment, the physician’s communication role is to provide an atmosphere in which confidence and competence is built, emotional support given, and in which support for choice, control, and responsibility for health behaviour is recognized and reinforced. Key skills are those related to relationship‐building to provide emotional support and reassurance and partnering skills to enhance behavioural competence and confidence in following through on an action plan.

Conclusions

The incorporation of patient preferences into treatment decisions is far from simple or direct. Patients are not all of one mind in this matter, nor are individual patients always consistent in their preferences. 4 , 5 , 27 Although most patients will express a desire (to interviewers) for more information about their illness and treatment options than they are generally given by their physician, they rarely explicitly demand either more information or increased involvement in decision‐making. 5 , 19 , 27 Moreover, physicians are largely unaware of patients views on these matters, and their time, commitment, and capability to elicit patients’ preferred choices appears limited. 4 , 27

Fortunately, physician training in patient‐ centred communication skills may provide the mechanism of address for these difficulties. Whilst communication skills still constitute only a small part of most medical school curriculum, its’ contribution has increased steadily over the past 30 years to the point where virtually all medical schools offer some kind of interviewing skills training. 28 , 29 Evidence suggests that teaching of these skills can be effective 30 , 31, –32 and even short postgraduate training programmes can produce significant changes in the interviewing performance of clinically experienced physicians. 23 , 24, –25 , 33

Despite these training successes, medicine has been slow to embrace the patient‐centred paradigm of medicine, and the patient perspective is still largely absent. 8 , 10 , 26 The need for a paradigm shift may be all the more pressing as practice efficiencies pressure physicians to see more patients in shorter time periods. For Mechanic, 12 the consequences of time pressures go to the very core of the doctor‐patient relationship by undermining patient trust and inhibiting patient disclosure of concerns, particularly of a sensitive psychosocial nature. Mechanic suggests that it is the socio‐emotional rather than the technical aspects of care which are most likely to be abandoned under time pressures, further reinforcing the most alienating aspects of the biomedical model of care and undermining the possibility of negotiating perspectives and the definition of patient need. Similarly, Emanuel and Dubler 13 suggest that time efficiencies may act to encourage medical paternalism by limiting discussion of patient values, alternative treatments, or the impact of therapy on the patient’s overall life. Arguments for a more patient‐centred and mutual medicine are not limited to societal demand and ethical deliberations, although these are indeed present and convincing. Patient‐centred medicine and its associated communication skills are important because they are linked to both patient and physician well‐being. 34 Stewart’s 35 comprehensive review of physician‐patient communication interventions found strong supporting evidence linking patient‐centred communication elements with a variety of patient health outcomes, including emotional health, symptom resolution, function, physiologic measures (i.e. blood pressure and blood sugar level) and pain control. The supportive function of communication may be seen at the intersection of the patient’s experience and the physician’s expertise. Patient‐centred skills hold the key to personal, responsive, and fulfilling communication between patients and physicians. These skills will continue to be the most meaningful training challenge to help nurture and develop the capacity of meaningful autonomy and sensitive and respectful medical care.

References

- 1. Maloney T & Paul B. Rebuilding public trust and confidence. In: Gerteis M, Edman‐Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco T (eds) Through the Patient’s Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient‐Centred Care. San Francisco (CA): Jossey‐Bass, 1993: 280–293.

- 2. Hamilton E, Cairns H, Emaunel EJ (translator). Plato: the Collected Dialogues. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 1961: 720 c‐e.

- 3. Caplan A. Can autonomy be saved? In: If I Were a Rich Man Could I Buy a Pancreas? and Other Essays on the Ethics of Health Care. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992: 259.

- 4. Schneider CE. The Practice of Autonomy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- 5. Roter DL & Hall JA. Doctors Talking to Patients/ Patients Talking to Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits Westport: Auburn House, 1992.

- 6. Parsons T. The Social System. Glencoe: The Free Press, 1951.

- 7. Freidson E. Professional Dominance. Chicago: Aldine Press, 1970.

- 8. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science, 1977; 196: 129 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mishler EG. The Discourse of Medicine: Dialectics of Medical Interviews Norwood: Ablex, 1984.

- 10. McWhinney I. The need for a transformed clinical method. In: Stewart M, Roter D (eds) Communicating with Medical Patients. Newbury Park: Sage, 1989.

- 11. US Government . President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioural Research. Making Health Care Decisions and Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient‐Practitioner Relationship Vol. 1. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1982.

- 12. Mechanic D. Changing Medical Organization and the Erosion of Trust. The Milbank Quarterly, 1996; 74: 171 189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Emanuel EJ & Dubler NN. Preserving the physician‐patient relationship in the era of managed care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1995; 273: 323 329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum Press, 1983.

- 15. Wallerstein N & Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly, 1988; 15: 379 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roter DL. Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS). Coding Manual. Baltimore (MD) Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, 1999.

- 17. Engel GL. How much longer must medicine’s science be bound by a seventeenth‐century world view? In: White K (ed.) The Task of Medicine: Dialogue at Wickenburg. Menlo Park: The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 1988.

- 18. Lazare A, Putnam SM, Lipkin M. Three functions of the medical interview. In: Lipkin M, Putnam S, Lazare A (eds) The Medical Interview: Clinical Care, Education, and Research. New York: Springer‐Verlag, 1995: 3–19.

- 19. Roter DL. Patient participation in the patient–provider interaction: the effects of patient question asking on the quality of interaction, satisfaction, and compliance. Health Education Monographs, 1977; 50: 281 315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care: Effects on patient outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1985; 102: 520 528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beckman HB, Frankel RM, Darnley J. The effect of physician behaviour on the collection of data. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1984; 101: 692 696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers W, Ware JE. Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision‐making styles. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1996; 124: 497 504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1995; 155: 1877 1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levinson W & Roter D. The effects of two continuing medical education programmes on communication skills of practising primary care physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1993; 8: 318 324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roter DL, Cole KA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Grayson M. An evaluation of residency training in interviewing skills and the psychosocial domain of medical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1990; 5: 347 454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tresolini CP. …and the Pew‐Fetzer Task Force on Advancing Psychosocial Health Education. Health Professions Education and Relationship‐Centred Care San Francisco: Pew Health Professions Commission, 1994.

- 27. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P. Shared decision‐making in primary care: the neglected second half of the consultation. British Journal of General Practice, 1999; 49: 477 482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Makoul G & Schofield T. Communication teaching and assessment in medical education: an international consensus statement. Patient Education and Counselling, 1999; 137: 191 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Novack DH, Volk G, Drossman DA, Lipkin M Jr. Medical interviewing and interpersonal skills teaching in US medical schools: progress, problems and promise. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1993; 269: 2101 2105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lipkin M, Kaplan C, Clark W, Novack DH. Teaching medical interviewing: the Lipkin Model. In: Lipkin M, Putnam S, Lazare A (eds) The Medical Interview: Clinical Care, Education and Research. New York: Springer‐Verlag, 1995: 422–435.

- 31. Stewart M, Brown BJ, Weston WW, McWhinney I, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR (eds) Patient‐Centred Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1995.

- 32. Kurtz SM, Silverman JD, Draper JD. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

- 33. Hulsman RL, Ros WJG, Winnubst AM, Bensing JM. Teaching clinically experienced physicians communication skills. A review of evaluation studies. Medical Education, 1999; 33: 655 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta‐analysis of correlates of provider behaviour in medical encounters. Medical Care, 1988; 26: 657 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stewart MA. Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 1996; 152: 1423 1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]