Wellness is “the active process of becoming aware of and making choices toward a successful existence, both as individuals within society and within the work environment” (1). Wellness enhances physical, mental, and social well-being, and in one word, “health.” In recent years, wellness has moved into the workplace as enterprises — meaning both for-profit and not-for-profit companies, businesses, firms, institutions and organizations designed to provide goods and/or services — have recognized the role that the workplace can play in supporting worker health. While enterprises have the responsibility to provide safe and hazard-free work environments, they also have the opportunity to promote worker health and foster healthy workplaces (2). The average person spends more time working than any other daily activity of life (3), and, over a lifetime, an average of 90 000 hours on the job (4). The workplace, therefore, is an important setting, not only for health protection — to prevent occupational injury — but also health promotion —to improve overall health and well-being (2,5).

The concept of the healthy workplace is not new, but it has indeed changed, evolving from a nearly exclusive focus on occupational health and safety (managing the physical, chemical, biological, and ergonomic hazards of the workplace) to include work organization, workplace culture, lifestyle, and the community, all of which can profoundly influence worker health (6). Today’s healthy workplace includes both health protection and promotion (6). In short, it includes wellness.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has captured these elements in its definition of the healthy workplace. Based on a systematic literature and expert review, WHO proposes the following definition (5,6):

A healthy workplace is one in which workers and managers collaborate to use a continual improvement process to protect and promote the health, safety and well-being of all workers and the sustainability of the workplace by considering the following, based on identified needs:

Health and safety concerns in the physical work environment;

Health, safety and well-being concerns in the psychosocial work environment, including organization of work and workplace culture;

Personal health resources in the workplace; and

Ways of participating in the community to improve the health of workers, their families and other members of the community.

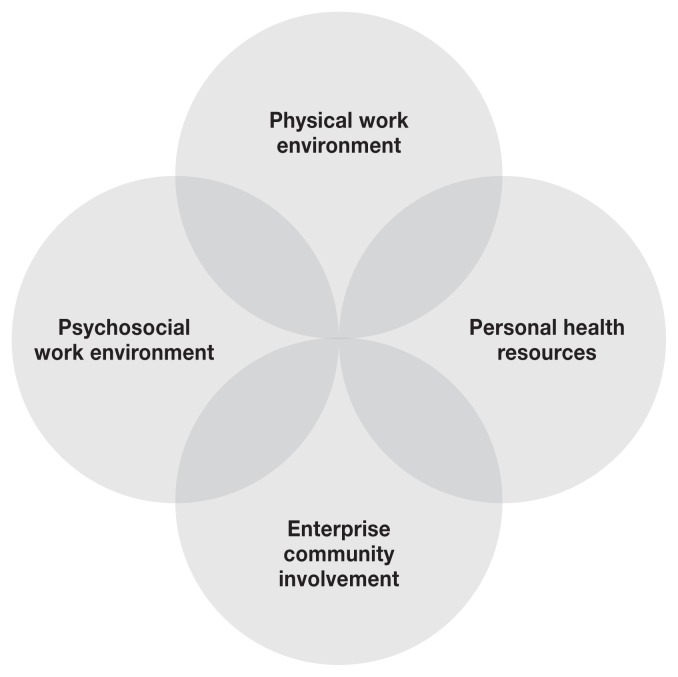

Based on this definition, healthy workplace initiatives can be cultivated in four spheres of influence (6, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spheres of influence for a healthy workplace.

Physical work environment

Psychosocial work environment

Personal health resources

Enterprise community involvement

Physical work environment

Many kinds of physical hazards can threaten the health and safety of workers. Examples of such hazards include electrical dangers; ergonomic-related risks (e.g., repetitive motion, awkward posture, or excessive force); radiation exposure, machine-related injuries; and the risk of a work-related motor vehicle crash. These hazards need to be recognized, assessed, minimized, eliminated, or controlled (6,7).

Psychosocial work environment

“Psychosocial hazards” can also threaten the health and safety of workers. These are better known as work stressors and are related to the psychological and social conditions of the workplace, including the organizational culture and the attitudes, values, beliefs and daily practices, as opposed to the physical conditions of the workplace (6). They can be harmful to the mental and physical health of workers, with evidence of 2 to 3 times greater risk of mental illness, injuries, back pain, and workplace conflict and violence (6).

As derived directly from the WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model (6):

Examples of psychosocial hazards include but are not limited to:

Poor work organization (problems with work demands, time pressure, decision latitude, reward and recognition, support from supervisors, job clarity, job design, poor communication)

Organizational culture (lack of policies and practice related to dignity or respect for all workers, harassment and bullying, gender discrimination, intolerance for ethnic or religious diversity, lack of support for healthy lifestyles)

Command and control management style (lack of consultation, negotiation, two-way communication, constructive feedback, and respectful performance management)

Lack of support for work/life balance

Examples of ways to influence the psychosocial work environment:

-

Eliminate or modify at the source:

– Reallocate work to reduce workload, remove supervisors or retrain them in communication and leadership skills, enforce zero tolerance for workplace harassment and discrimination

-

Lessen impact on workers:

– Allow flexibility to deal with work/life conflict situations; provide supervisory and co-worker support (resources and emotional support); allow flexibility in the location and timing of work; and provide timely, open, and honest communication

Protect workers by raising awareness and providing training to workers, for example regarding conflict prevention or harassment situations

Personal health resources

The provision of personal health resources in the workplace can support or motivate worker efforts to improve or maintain their personal health practices or lifestyle, as well as monitor and support their physical and mental health (6,7). Such resources include health services, information, opportunities, and flexibility. Although work can get in the way of making healthy lifestyle choices, motivated and innovative employers do what they can to remove the barriers and support the personal health goals of their employees.

As derived directly from the WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model (6):

Examples of personal health resource issues in the workplace:

Employment conditions or lack of knowledge may make it difficult for workers to adopt healthy lifestyles or remain healthy. For example:

Physical inactivity may result from long work hours, cost of fitness facilities or equipment, and lack of flexibility in when and how long breaks can be taken

Poor diet may result from lack of access to healthy snacks or meals at work, lack of time to take breaks for meals, lack of refrigeration to store healthy foods, or lack of knowledge

Examples of ways to enhance workplace personal health resources:

These may include medical services, information, training, financial support, facilities, policy support, flexibility, and promotional programs to enable and encourage workers to develop healthy lifestyle practices. Some examples are:

Provide fitness facilities for workers or a financial subsidy for fitness classes or equipment

Encourage walking and cycling in the course of work functions by adapting workload and processes

Provide and subsidize healthy food choices in cafeterias and vending machines

Allow flexibility in timing and length of work breaks to allow for exercise

Enterprise involvement in the community

Community involvement refers to the ways in which a workplace goes above and beyond to involve itself within the community in which it operates, offering expertise and resources (beyond its day-to-day offerings) to support the social and physical well being of the community (6). Activities that positively influence the physical and mental health, safety, and well-being of workers and their families offer the greatest advantage. Examples include spearheading a community project and volunteering in community initiatives to benefit those in need.

Ultimately, as stated in the WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model (Burton, 2010):

A healthy workplace aims to:

Create a healthy, supportive, and safe work environment

Ensure that health protection and health promotion become an integral part of management practices

Foster work styles and lifestyles conducive to health

Ensure total organizational participation

Extend positive impacts to the local and surrounding community and environment

Those in veterinary medicine might ask, “But how does all of this apply to me in the veterinary workplace? Why would I want to think beyond the necessities of occupational health and safety when there’s already more than enough to think about — and do — with running a practice?” These are valid questions, and the answers are just as important as the questions.

First, it is the right thing to do. Ensuring employee health and safety follows one of the most basic of universally accepted ethical principles, “do no harm” (6). There is a moral imperative to create healthy veterinary workplaces that do not harm the mental or physical health, safety, or well-being of its employees (6).

Second, it is the smart thing to do. Worker health, safety and well-being not only benefit workers and their families but also have substantial implications for the productivity, competitiveness and sustainability of enterprises (5). There is a wealth of data demonstrating that in the long term, businesses that protect and promote employee health tend to be the most successful (6). They have the most physically and mentally healthy and satisfied employees; less sick leave, disability, and turnover; and higher productivity and quality of products and services (6,7). As recognized by the WHO, “The wealth of business depends on the health of workers” (6). Accordingly, to support workers is to support the enterprise. The two are inextricably entwined. Businesses that do not protect and promote employee health incur significant costs on multiple levels.

And third, it is the legal thing to do (sort of!). A safe and healthy work environment is considered a fundamental human right (8). The legislation varies tremendously across geographies, but at minimum, there is always legislation requiring employers to protect workers from hazards in the workplace that could cause injury or illness.

Accreditation Canada, an independent, not-for-profit organization that accredits health care and social services organizations across Canada, addresses the need for health care organizations to create a culture that supports a safe and healthy work environment (9). A safe and healthy work environment is classified as “a strategic and high priority.” The situation is the same in the United States. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, an independent, not-for-profit organization that accredits and certifies nearly 21 000 health care organizations and programs in the US (10), mandates that hospitals have processes to promote physician wellness (11). To this author’s knowledge, the veterinary accreditation bodies of North America do not refer to the necessity of including processes to promote veterinary wellness or create organizational cultures that support a safe and healthy work environment. This does not mean, however, that we can be complacent. On the contrary, we have the opportunity to follow the lead in medicine — and even take the lead with the ability to customize, from the ground up, the most personal, creative, meaningful, and sustainable wellness initiatives that best meet employees’ needs and interests.

To clarify, it’s not that work is generally regarded as bad for physical and mental health and well-being. On the contrary, when compared to worklessness or unemployment, work is good for physical and mental health and well-being (12). Work is usually the main source of income to make a living and fully participate in society, and it is strongly connected to individual identity and social status (12). However, it can have harmful as well as beneficial effects on health and well-being depending on the workplace. There are costs in all directions — for workers, the workplace, the community, and beyond — if worker health and wellness and the imperative to create healthy workplaces are disregarded.

Increasingly, enterprises large and small and from all sectors are bringing wellness into the workplace (13). It’s time we take a critical view of what we, in the veterinary profession, are doing to promote health and well-being in the workplace, and ask ourselves what else we can be doing. Along with the responsibility to provide safe and hazard-free workplaces, we have the opportunity to promote health and well-being and foster healthy workplaces. We can encompass the opportunities if we expand our circles of responsibility. In so doing, we meet the moral imperative to create workplaces that do not harm the mental or physical health, safety, or well-being of our employees; we gainfully increase the productivity, competitiveness, and sustainability of our practices; and we take the lead in our profession.

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.American Veterinary Medical Association. Guiding Principles for State Veterinary Wellness Programs. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: https://www.avma.org/ProfessionalDevelopment/Personal/PeerAndWellness/Pages/wellnessprinciples.aspx.

- 2.Workplace Health Model. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Workplace Health Promotion. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/model/

- 3.Bureau of Labour Statistics: American Time Use Survey. United States Department of Labour; [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/tus/charts/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pryce-Jones J. Happiness at work: Maximizing your psychological capital for success. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healthy workplaces: A model for action. World Health Organization; [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/healthy_workplaces_model.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton J. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices. 2010. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/healthy_workplace_framework.pdf.

- 7.Burton J. The Business Case for a Healthy Workplace. 2008. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: http://www.iapa.ca/pdf/fd_business_case_healthy_workplace.pdf.

- 8.Seoul declaration on safety and health at work. XVIII World Congress on Safety and Health at Work; [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/statement/wcms_095910.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Accreditation Canada. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: https://www.accreditation.ca/

- 10.The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/

- 11.Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waddell G, Burton AK. Is work good for your health and well-being? Department of Work and Pensions; UK: 2006. [Last accessed September 20, 2016]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214326/hwwb-is-work-good-for-you.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caloyeras JP, Liu H, Exum E, Broderick M, Mattke S. Managing manifest diseases, but not health risks, saved PepsiCo money over seven years. Health Affairs. 2014;33:124–131. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]