Abstract

Violence against women by their husbands is a problem for women worldwide. However, the majority of women do not seek help. This article presents findings from a national survey in India on empowerment-related correlates of help-seeking behaviors for currently married women who experienced spousal violence. We examined individual-, relationship-, and state-level measures of empowerment on help-seeking from informal and formal sources. Findings indicate that help-seeking is largely not associated with typical measures of empowerment or socio-economic development, whereas state-level indicators of empowerment may influence help-seeking. Although not a target of this study, we also note that injury from violence and the severity of the violence were among the strongest factors related to seeking help. Taken together, the low prevalence of help-seeking and lack of strong individual-level correlates, apart from severe harm, suggests widespread barriers to seeking help. Interventions that affect social norms and reach women and men across social classes in society are needed in addition to any individual-level efforts to promote seeking help for spousal violence.

Keywords: domestic violence, cultural contexts, disclosure of domestic violence, intervention/treatment

Introduction

Spousal violence in the form of physical, sexual, and emotional violence is experienced by women in all socio-demographic and cultural groups, across the globe (Montalvo-Liendo, 2009). Spousal violence can have both immediate and long-term physical and psychological impairments for the woman and for any children in her household (Campbell, 2002; Danielson, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006). Data from household surveys in 10 countries indicate the lifetime prevalence of partner violence (physical or sexual partner violence or both) varied from 15% (Japan) to 71% (Ethiopia; Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). Recent results from India indicate that as of 2005-2006, 31% of ever-married women experienced physical spousal violence and 8% experienced sexual (Kimuna, Djamba, Ciciurkaite, & Cherukuri, 2013). Research also indicates that most women throughout the world who experience spousal violence do not seek help (Kishor & Johnson, 2004). Those who seek help often do so because of the severity or life-threatening nature of the abuse (Randell, Bledsoe, Shroff, & Pierce, 2012; Spencer, Shahrouri, Halasa, Khalaf, & Clark, 2014; Sylaska & Edwards, 2013). Lacking from this literature, however, is a comprehensive assessment of the role of empowerment in help-seeking for spousal violence. In fact, the basic relationship between empowerment and help-seeking has itself received little attention. This study begins to fill this gap.

Empowerment can be examined at the individual, interpersonal, and contextual levels. Researchers have applied measures of these three types of empowerment to examine the experience of marital violence (Visaria, 2008), as well as women's health care (Ahmed, Creanga, Gillespie, & Tsui, 2010; Fotso, Ezeh, & Essendi, 2009) and views on gender preferences and wife-beating (Gupta & Yesudian, 2006). To date, most research on the relationship between spousal violence and empowerment has focused on the individual or relationship level, such as income and education, or decision making (Krishnan, Subbiah, Khanum, Chandra, & Padian, 2012; Rocca, Rathod, Falle, Pande, & Krishnan, 2009; Schuler, Hashemi, & Badal, 1998; Sen, 1999; Visaria, 2008), and to a lesser extent, contextual aspects of empowerment (Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy, & Campbell, 2006; Rocca et al., 2009; Uthman, Moradi, & Lawoko, 2011). These studies and other comparative studies indicate that there is little consistency across cultures as to how aspects of empowerment are associated with violence (Abramsky et al., 2011; Hindin, Kishor, & Ansara, 2008; VanderEnde, Yount, Dynes, & Sibley, 2012). For example, in a study of intimate partner violence (IPV) in 10 countries, Hindin et al. (2008) found that more educated women in Bolivia and Zimbabwe were less likely to experience violence compared with women with less education, but the opposite was true in Haiti. In Malawi, women who made decisions jointly with their husbands were less likely to experience violence than women who made decisions alone. However, there was no association between decision making and spousal violence in Kenya, Rwanda, Zambia, or Zimbabwe (Hindin et al., 2008). Cross-cultural differences in the relationship between violence and empowerment may stem from differences in how inequalities between men and women operate to permit such violence.

Empowerment reflects a women's capacity to make “strategic life choices,” which are choices that allow her control over her life that may or may not be in accordance with prevailing social norms (Kabeer, 1999). Empowerment reflects both the process by which a woman achieves the capacity for decision making and control, such as going to school or accessing information, as well as the actualization of it, such as participation in household decision making and having autonomy to move freely in the community (Gupta & Yesudian, 2006; Jejeebhoy, 1998).

Kabeer's conceptualization of empowerment acknowledges that social norms in a woman's environment can constrain her personal aspects of empowerment (Liang, Goodman, Tummala-Narra, & Weintraub, 2005; Pinnewala, 2009). Within the household, a husband's controlling behaviors may directly shape a woman's empowerment, as his controlling actions seek to limit her opportunities and freedom of movement (International Institute for Population Sciences [IIPS] & Macro International, 2007). Outside the household, societal norms that permit controlling behaviors by husbands facilitate the institutionalization of structural inequalities between men and women. Such cultural beliefs about gender roles permeate other layers of social interaction (Jewkes, 2002; Koenig et al., 2006; Olayanju, Naguib, Nguyen, Bali, & Vung, 2013). Individual empowerment may only be realized as far as the prevailing social norms allow. To date, the examination of state-level gender equality and IPV has been very limited, but one study found that greater gender equity was related to lower violence (Ackerson & Subramanian, 2008; Martinez, 2008). Other research has found a positive relationship between gender equality and prenatal care (Gubhaju & Matthews, 2009) and the division of household labor (Ruppanner, 2010).

Kishor and Subaiya (2008) developed measures purposefully for operationalizing women's empowerment; these measures are explicitly used as indicators of empowerment in the survey on which this study is based. This study applies these indicators as individual characteristics (e.g., resources of education, wealth and living arrangements) and evidence of empowerment in women's interpersonal relationships with their partner (e.g., participation in household decision making and autonomy). Kishor and Subaiya also recognize the need to consider contextual conditions that affect women's empowerment as well (Kishor & Subaiya, 2008).

Empowerment and Help-Seeking

Although there are several theoretical frameworks that inform research on spousal violence and a woman's response to it, there has been little development of theory explicitly linking empowerment to help-seeking for spousal violence (Pinnewala, 2009). However, researchers have examined the association of empowerment with other aspects of women's care seeking, such as maternal and child health care (Ahmed et al., 2010; Fotso et al., 2009; Furuta & Salway, 2006; Ghuman, 2003). Here we draw on general models of help-seeking to begin to understand the connections between empowerment and help-seeking for spousal violence.

Pinnewala (2009) reviewed three theoretical models (i.e., the ecological, stress-coping, and the transtheoretical models) on help-seeking for partner violence among South Asian women and identified consistent features across the models that affected a woman's response, including internal cognitive processes and contextual factors.(Pinnewala, 2009). Similarly, Liang et al. (2005) described help-seeking as an outcome of the confluence of factors, including a woman's recognition of the problem, her available social support, and contextual environment. Cognitive processes include a woman's perception or identification of the abuse, coping mechanisms, and cognitively framing abuse as a problem that requires a response. Individual empowerment can influence the recognition that spousal violence is a problem by providing a woman with the capacity to reject social norms that dictate an unequal division of power and rights between men and women (Kishor & Subaiya, 2008). Identification that spousal violence is a problem that should be rectified signals a married woman's conscious rejection of social norms that may condone it.

Contextual factors are social forces and structures that influence her capacity to seek help, such as the marital relationship, her social support, social institutions, and the broader cultural views on gender norms and patriarchal social structures. Contextual factors are a prominent feature of the ecological model of gender-based violence (Heise, 1998) and frame the analysis of this study. For example, interpersonal empowerment, for example, as visible through a woman's ability to participate in decisions in her marital relationship or have contact with the outside community, may provide psychological or material resources for help-seeking. Contextual factors that influence a woman's empowerment, such as strong patriarchal norms, may also discourage help-seeking (Pinnewala, 2009). However, research to date has not comprehensively examined the relationship between empowerment and help-seeking, including in India.

Spousal Violence and Help-Seeking in India

Spousal violence in India is widespread, and the majority of women who experience abuse endure it repeatedly for several months or longer before seeking help (Kamat, Ferreira, Mashelkar, Pinto, & Pirankar, 2013; Krishnan et al., 2012; Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005). As of the 2005-2006 India National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) Final Report, only 23% of currently married women (aged 15-49) who experienced spousal violence sought help from any source, with little variation in help-seeking across socio-demographic characteristics (IIPS & Macro International, 2007).

When Indian women do seek help, it is usually from informal sources, such as other family members or close friends, as women often believe violence to be a problem best resolved within the family (Krishnan et al., 2012). For example, in a study in Goa, the most common reason abused women (n = 197) gave for not seeking help (n = 135, or about 69%) was to avoid distressing their parents and to maintain the family coherence (Kamat et al., 2013). However, seeking help from family may provide only minimal support; in a study of married women seeking help in Chennai in Tamil Nadu (n = 90), about half of the women found family members to be only moderately useful (Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005). The limited response of family members and institutions to spousal abuse reflects strong cultural norms that encourage acceptance of violent behaviors and discourage confronting situations of abuse (Kapadia-Kundu, Khale, Upadhaye, & Chavan, 2007; A. Mitra & Singh, 2007; Tichy, Becker, & Sisco, 2009). Social norms, stemming from cultural and religious traditions, emphasize that a woman should be submissive to her husband (Ahmed-Ghosh, 2004; Kanagaratnam et al., 2012). Patriarchal norms also dictate a lower status for women (Ahmed-Ghosh, 2004; Jejeebhoy, Santhya, & Sabarwal, 2013). Women often marry young and are expected to raise children, take care of the domestic chores, and respect their husband and his family (Go et al., 2003; Krishnan et al., 2012). Women's lower status in society and inequality in social opportunities leave women less empowered in domestic relationships, which perhaps “underlie” partner violence (Krishnan et al., 2012; Pallitto & O'Campo, 2005) and likely hinder help-seeking.

Help-seeking from formal authorities is rare, and many women do not view the police or help centers as acceptable resources (Chandrasekaran, 2013). In the Chennai city study, about 66% of women thought the police were “less useful or useless” (Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005). In the NFHS-3, only 2% of women went to the police (IIPS & Macro International, 2007). Few women seek help at health care facilities, in part due to the lack of training on care for victims or referral networks (Chibber, Krishnan, & Minkler, 2011; Krishnan et al., 2012). It may also be difficult for women to disclose, even if resources are available. In a survey of women in Gujarat who were seeking health care at a community organization, only 8.4% ever sought help for IPV at such organizations (Kamimura, Ganta, Myers, & Thomas, 2014). Few women resort to any legal action, as legal counsel often does not take them seriously (Bhatia, 2012; Rao, 1997). The present study is situated within the Indian context to examine the relationship between measures of empowerment and help-seeking behavior of spousal violence victims.

The Present Study

To address the gap in the literature on the relationship between empowerment and help-seeking for violence, we use nationally representative data on married women of child-bearing age from India to examine individual-, relationship- and state-level measures of empowerment on women's help-seeking for spousal violence in India. We also analyze the interaction effect of relationship and state-level measures of empowerment on help-seeking to understand if relationship-level empowerment measures are moderated by contextual measures of empowerment. We examine separately the influence of these measures on help-seeking from informal (family or friends) and formal sources (institutional resources), as the literature suggests that there are qualitative differences in the characteristics and circumstances under which women seek help from formal authorities. We build on smaller, within-state, qualitative studies of help-seeking that have provided powerful and useful insights (Chibber et al., 2011; Naved, Azim, Bhuiya, & Persson, 2006; Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005; Pandey, Dutt, & Banerjee, 2009). Specifically, this article examines the following research questions:

Research Question 1: What are the independent associations of individual-, relationship-, and state-level empowerment measures with help-seeking for spousal violence among women in India?

Research Question 2: Do state-level aspects of empowerment moderate the influence of empowerment at the spousal relationship level for help-seeking behaviors?

In summary, multiple individual and contextual factors influence help-seeking. This exploratory study examines whether empowerment will be positively associated with help-seeking. Given previous evidence of the role of empowerment for other aspects of women health and socio-economic outcomes, we speculate that empowerment at the individual level may promote help-seeking, but this may be moderated or dampened in social contexts where spousal violence is socially condoned.

Method

Data

This study uses the 2005-2006 India NFHS-3, a nationally representative stratified household survey that uses in-person (face-to-face) interviews. In sampled households, interviews are conducted with all women aged 15 to 49 who were residents or visitors who spent the preceding night in the household. In each sampled households, one women aged 15 to 49 was selected to be interviewed for a domestic violence survey module (n = 83,703).

We restricted the analysis to women who were currently married and reported any physical or sexual violence by their husband (n = 21,376). We restricted it further to women whose interviews were not interrupted by another household member (n = 1,059) and who were not missing data on help-seeking responses (n = 269) or background characteristics (n = 915), leaving a study sample of 19,133 women for analysis.

Dependent variables

The NFHS-3 domestic violence questions are based on the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus & Douglas, 2004), which includes questions on whether the woman ever experienced emotional, physical, and sexual violence. The questions on domestic violence and the use of the Conflict Tactics Scales were informed by World Health Organization (World Health Organization,2001) guidelines on collection of such sensitive information and by research on valid and reliable measurement of domestic violence (Hindin et al., 2008). Violence was defined by self-reports that the woman was pushed, shook, slapped, hit with a fist or something harmful, kicked or dragged, had an object thrown at hear, or her husband attempted to strangle or burn, threatened her with a knife, gun or other weapon, or forced sex or other sexual acts.

Women who had experienced violence were asked about help-seeking with the question, “Thinking about what you yourself have experienced, among the different things we have been talking about, have you ever tried to seek help to stop the person from doing this to you again?” If the woman answered affirmatively, she was asked, “From whom have you sought help to stop this?” followed by a probe (“Anyone else?”) to ensure all responses were collected. The woman can identify as many persons contacted for help as necessary. Help-seeking was then categorized as informal (family, her husband's family, neighbors, and friends) and formal (police, lawyers, religious leaders, and health care professionals). Cronbach's alpha was .99 for both dependent variables. About 97% of women who sought help from informal sources did not seek formal help, whereas about 34% of women who sought formal help did not seek informal help. Given this pattern, women who sought help from both informal and formal sources were coded as having sought formal help (only 58 of the 170 women sought help from formal sources only).

Independent variables

Individual-level empowerment measures

We included the woman's educational attainment (continuous), her wealth quintile (ordinal; Kishor & Johnson, 2006), whether she has her own money, and exposure to media (whether she has read a newspaper or listened to the radio or watched television at least once in the past week; Kishor & Subaiya, 2008).

Relationship-level empowerment measures

We used a continuous measure of her spouse's educational attainment (in years) and a dichotomous measure of whether she has less education than her spouse. We included a binary indicator of early marriage (before age 18), as well as the age difference of the couple (in years; Pandey, Dutt, and Banerjee, 2009). Early marriage (before age 18) can be disempowering to a women and preclude her attaining education or other life goals (Desai & Andrist, 2010). Since 1978, laws in India have prohibited girls’ marriage before age 18 (UNICEF, 2001). However, in 2005-2006, about 45% of women aged 20 to 24 were married before age 18 (Raj, Saggurti, Balaiah, & Silverman, 2009).

The woman's justification of wife-beating (tolerance toward it) was measured through a question on whether a man is ever justified in beating his wife for any of seven specific reasons: if she goes out alone, neglects the kids, burns the food, argues with him, refuses sex, is unfaithful, or disrespects her in-laws. Cronbach's alpha was .85. We used a dichotomous indicator to indicate the woman's justification of wife-beating under any condition (Abramsky et al., 2011).1 A positive response to any question was coded 1, and coded 0 otherwise. We included her justification on wife-beating as a relationship-level measure reflecting acceptance or rejection of spousal violence as it indicative empowerment to counter social norms that condone violence by husbands toward wives (Kishor & Subaiya, 2008; Sen, 1999).

Decision making in the spousal relationship was modeled as a count of responses to five items related to decisions in which the wife participates. These decisions included obtaining health care for herself, major household purchases, visits to her family or relatives, how to spend the money her husband earns, and using contraception (Ahmed et al., 2010; Schatz & Williams, 2009). Cronbach's alpha was .80. For each decision, the woman was asked if the couple decides jointly, if the woman makes those decisions by herself, or if her husband/someone else decides. If she reported deciding alone or jointly, then she participated in decision making, which was coded 1 and 0 otherwise, and these were summed. Although some of these items may be a stronger indicator of empowerment, in the absence of an appropriate weighting approach, all decisions had equal weight.

Freedom of movement was modeled as a count of responses to four questions on places to which the respondent could go alone, including to the market, to a medical facility, out alone into the community, and to seek health care for herself. Cronbach's alpha was .77. A summary score (0-4) was computed (so a higher score meant more freedom of movement).

For controlling behaviors, we used six questions on the husband's level of trust and restrictiveness that intended to capture the extent of his spousal control. The husband's controlling behavior was modeled as a count of responses as to whether her husband becomes jealous or angry if she talks to other men, frequently accuses her of being unfaithful, does not permit her to meet her female friends, tries to limit her contacts with her family, insists on knowing where she is at all times, and does not trust her with any money. Cronbach's alpha was .72. A summary score (0-6) was computed, with a higher score reflecting a more controlling husband. All spousal characteristics were reported by the woman.2

State-level empowerment measures

India is divided into 29 states, which are the first-level administrative units and which exercise considerable autonomy. There is substantial variation among the states with respect to development and gender equality. For each state, we calculated the percentage of women in the survey (age 15-49) who justify wife-beating for any reason and the state-level prevalence of IPV.3 We also merged state-level data of the Gender Development Index (GDI) and Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM; Ministry of Women & Child Development, 2009). We use the GDI and GEM that were developed by the Government of India (GOI), partly in response to criticisms of earlier GDI and GEM developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP; for example, Geske Dijkstra, 2006; Syed, 2010). The GDI assesses gender disparities in development based on infant mortality, life expectancy, literacy, education, and estimated earned income per capita differences between men and women. The GEM assesses three areas of gender inequality in the ability to participate in economic and political spheres: political participation and decision-making power, economic participation and decision-making power, and power over economic resources. The appendix provides a listing of the indicators for each dimension. Higher GEM values reflect greater empowerment at the state level for women.

Background Control Variables

We included in the model other individual and household characteristics and characteristics of the violence that were conceptually or empirically identified in the literature as associated with IPV and help-seeking (for conceptual and empirical reviews, see Heise, 2011, and Pinnewala, 2009). Little is known about the relationship of these characteristics with help-seeking in India, and their relationship with IPV is not consistent. Examining the potential mediating and moderating impacts of these factors is beyond the scope of this article, but an important area for further research.

Individual characteristics

These included the following aspects of the woman's personal history: total number of children, age (continuous), employment (any form vs. not employed), and religion (i.e., Muslim, Hindu, Christian, Neo-Buddhist, and Other). Older women may be less likely to seek help due to tolerance or adjustment to the situation (Morrison, Luchok, Richter, & Parra-Medina, 2006). However, older women are more likely to have children, and the presence of children may promote help-seeking (Ellsberg et al., 2001). Women who have children may be more likely to seek help due to concerns for their safety and also fear reporting the violence due to concerns they would be taken away (Ahmed-Ghosh, 2004). Employment was treated as a background characteristic because of the mixed findings in the literature about whether employment indicated empowerment (Krishnan et al., 2012; Rocca et al., 2009). We also included a measure of whether the woman ever saw her father beat her mother. Women who saw their mother beat their father may be more likely to experience violence (Panda & Agarwal, 2005) or view abuse as fitting with social norms, and be less likely to seek help (Kapadia-Kundu et al., 2007).

We included a binary measure of severity of the violence, following the WHO classification (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006). Severe violence was indicated if the woman reported being slapped, hit with a fist or something harmful; kicked or dragged, strangled or burned; threatened with a knife; or forced sex or other sexual acts. Less severe violence was defined as reports of being shaken or having had an object thrown at her. We also included a measure of whether the woman ever experienced an injury from the violence and of whether her partner drinks alcohol. Qualitative studies indicate that women often seek help only when the violence becomes severe (Go et al., 2003; Heise, 2011; Tichy et al., 2009). Alcohol is known to play a role in many incidents of violence (Heise, 2011; Rao, 1997). Bivariate pairwise correlation for severity and injury was 0.35.

Household characteristics

These included a dichotomous indicator of urban versus rural location, the average educational level of the household members (continuous), and a dichotomous measure whether the woman has in-laws in the household. Women's help-seeking behaviors in India have not been examined in terms of these socio-demographic factors. For IPV, rural households are less likely to seek help (Kimuna et al., 2013), whereas women who live with in-laws may be more likely to experience violence (Mogford, 2011).

Analysis

First, we report the percentage of women who seek help from formal and informal sources by background measures and individual-, relationship-, and state-level empowerment measures. Then, for each source of help, we conceptually build a regression model: Model 1 included only background characteristics, and Model 2 examined the empowerment measures, controlling for background characteristics.4 Finally, in Model 3, we tested whether relationship-level empowerment measures that were statistically significant in Model 2 were moderated by the state-level measures of acceptance of wife-beating and the GEM using interaction terms.

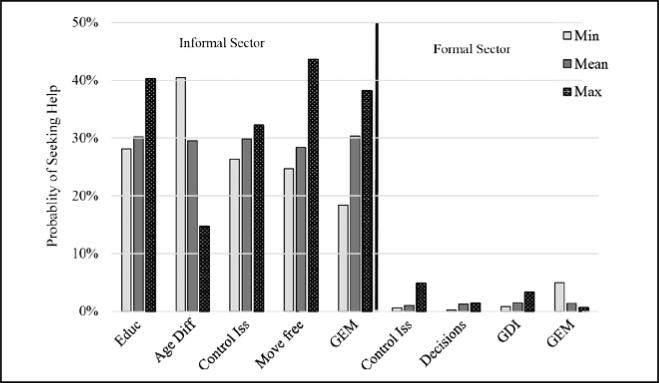

We computed the predicted probabilities of help-seeking from the odds ratios of Model 3. Odds ratios are informative as to the relative size and direction of the effects, but they do not inform us about the percentage of women who seek help for specific values of the predictor variables. The probability calculated here is the average marginal effect while holding the values for all other variables as constants.

All analyses were performed in Stata v.12.0 (StataCorp, 2012).

Results

Table 1 shows the percentage of women who sought help according to measures of socio-demographic, partner, empowerment, and state-level characteristics. The p value for each characteristic reflects whether the bivariate association between help-seeking and the characteristic was statistically significant, separately for each source of help (informal and formal sources). Overall, about 24% sought help for violence from any source, with the overwhelming majority from informal sources. For example, 37.4% of women who saw their father beat their mother sought help whereas 31.3% of women who did not see their father beat their mother sought help. As these are unadjusted analyses, we comment on few associations here. Most differences between those who seek help and those who do not are small, though statistically significant. Informal help-seekers were more likely to be Muslim, Buddhist, or other religion, to witnessed spousal violence as a child, to be employed, to have experienced severe violence or injury, and to have a husband who drinks alcohol. Informal help-seekers were also more likely to reside in households with a higher average educational attainment, and to co-reside with their in-laws. Women in wealthier households, those who participated in decision making, or who had husbands with more education or were older were less likely to seek help. Women whose husbands had more control issues, who had their own money, or had more autonomy were more likely to seek help as well. Informal help-seekers were also more likely to live in states that were more tolerant of wife-beating and had lower GEM scores.

Table 1.

Percentage of Currently Married Women Aged 15 to 49 Who Sought Help for Spousal Violence by Source of Help and Selected Characteristics, India, 2005-2006 (N = 20,048).

| Informal | Formal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did Not Seek Help (n = 14,842) | Sought Help (n = 44,291) | Did Not Seek Help (n = 18,963) | Sought Help (n = 170) | |||

| M or % | M or % | p Value | M or % | M or % | p Value | |

| Overall | 77.1% | 22.9% | 98.8% | 1.1% | ||

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Age (M) | 31.5 | 31.4 | .918 | 31.5 | 34.3 | .007 |

| Total no. of children (M) | 3.2 | 3.3 | .558 | 3.3 | 3.1 | .007 |

| Religion (%) | ||||||

| Hindu | 81.4 | 81.6 | .098 | 81.4 | 81.8 | .938 |

| Muslim | 14.5 | 12.7 | .001 | 14.1 | 13.9 | .987 |

| Christian | 1.6 | 2.6 | .120 | 1.8 | 1.9 | .393 |

| Buddhist/neo-Buddhist | 1.0 | 0.7 | .001 | 0.9 | 1.8 | .103 |

| Other | 1.6 | 2.4 | .000 | 1.8 | 0.7 | .495 |

| Wife saw father beat her mother (%) | 31.3 | 37.4 | .000 | 32.8 | 29.8 | .495 |

| Employed (%) | 40.5 | 43.7 | .014 | 44.0 | 56.0 | .001 |

| Wife experience severe violence (%)a | 87.1 | 90.8 | .000 | 88.0 | 100.0 | NA |

| Wife experienced injury (%) | 28.0 | 59.1 | .000 | 34.7 | 79.2 | .000 |

| Husband drinks alcohol (%) | 41.5 | 56.6 | .000 | 44.8 | 65.1 | .000 |

| Household characteristics | ||||||

| Urban (%) | 26.1 | 25.3 | .491 | 25.9 | 32.0 | .131 |

| Average education of household (years) | 3.7 | 3.5 | .033 | 3.6 | 4.2 | .000 |

| Daughter-in-law of the householder (%) | 36.7 | 33.3 | .007 | 36.0 | 27.1 | .063 |

| Empowerment measures | ||||||

| Individual-level empowerment | ||||||

| Education level (0-23) | 3.0 | 2.9 | .258 | 3.7 | 3.5 | .021 |

| Wealth quintile (M) | 2.7 | 2.6 | .040 | 2.7 | 2.7 | .429 |

| Exposed to media (%) | 43.7 | 44.3 | .682 | 43.8 | 53.1 | .039 |

| Relationship-level empowerment | ||||||

| Husband education level (0-24) | 5.5 | 5.0 | .000 | 5.4 | 5.4 | .602 |

| Husband has more education (%) | 43.0 | 40.1 | .000 | 42.4 | 38.9 | .470 |

| Husband older in age (mean years) | 5.8 | 5.5 | .018 | 5.7 | 6.5 | .079 |

| Early marriage (<18 years old) | 67.7 | 67.2 | .655 | 67.6 | 63.7 | .348 |

| No. of control issues (0-6) | 1.2 | 1.7 | .000 | 1.3 | 2.7 | .000 |

| Wife participates in decision making (%) | 88.7 | 84.9 | .042 | 87.9 | 73.4 | .017 |

| Wife has money for own use (%) | 45.1 | 48.0 | .031 | 45.8 | 47.5 | .697 |

| No. of ways wife moves freely (0-4) | 2.1 | 2.3 | .000 | 2.2 | 2.8 | .000 |

| Wife's tolerance of IPV for any reason (%) | 37.3 | 35.7 | .197 | 63.2 | 55.7 | .095 |

| State-level empowerment | ||||||

| % of women who tolerate IPV | 49.6 | 51.1 | .000 | 50.0 | 51.5 | .127 |

| % of women who experienced IPV | 39.7 | 40.0 | .759 | 39.8 | 37.4 | .004 |

| Gender Development Index (0-1) | 0.567 | 0.567 | .982 | 0.566 | 0.596 | .000 |

| Gender Empowerment Measure (0-1) | 0.458 | 0.462 | .048 | 0.459 | 0.464 | .351 |

Source. Authors’ analysis of the 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey.

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Severe violence is defined as punched, kicked, dragged, attempts to strangle or burn, or threatened with a knife, gun, or other weapon.

Findings were similar across background characteristics for the formal help-seekers, except that older age and higher mean number of children were also related to help-seeking but religion and witnessing spousal violence as a child were not. Across empowerment measures, women with less education, who were exposed to media, whose husbands had more control issues, or who had more autonomy were more likely to seek help. Women in more developed states or with lower prevalence of IPV were also more likely to seek help.

Table 2 presents the adjusted effects of significant background and individual, relationship, and state-level empowerment measures on help-seeking. The odds ratios shown in Table 2 were adjusted for background control variables, although findings did not substantially change from the unadjusted models presented above.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Help-Seeking for Spousal Violence Among Currently Married Women Aged 15 to 49 in India, by Source of Help, 2005-2006.

| Informal | Formal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| AOR | p Value | AOR | p Value | AOR | p Value | OR | p Value | |

| Women's empowerment characteristics | ||||||||

| Educational attainment | 1.02 | .073 | 1.04 | .364 | ||||

| Wealth | 1.01 | .807 | 0.96 | .736 | ||||

| Any media exposure | 1.06 | .422 | 0.83 | .517 | ||||

| Relationship level | ||||||||

| Husband's educational attainment | 0.99 | .183 | 1.02 | .615 | ||||

| Husband has more education | 1.03 | .740 | 1.04 | .916 | ||||

| Age difference (husband age – wife age) | 0.98** | .003 | 1.02 | .477 | ||||

| Early marriage (<18 years old) | 0.93 | .230 | 1.05 | .837 | ||||

| No. of husband's control issues | 1.17*** | .000 | 1.45*** | .000 | ||||

| Wife tolerates wife-beating (any reason) | 0.96 | .489 | 0.69 | .131 | ||||

| No. of ways wife can move freely | 1.07** | .006 | 1.28* | .015 | ||||

| Wife participates in decision making | 1.08 | .448 | 8.22** | .007 | ||||

| Has her money for own use | 0.97 | .630 | 0.89 | .632 | ||||

| State level | ||||||||

| % of women who tolerate IPV | 1.22** | .004 | 1.38 | .140 | ||||

| % of women who experience IPV | 1.01 | .294 | 0.99 | .378 | ||||

| Gender Development Index | 0.93 | .149 | 1.39* | .029 | ||||

| Gender Empowerment Measure | 1.23*** | .000 | 0.62*** | .001 | ||||

Note. Adjusted for age, total number of children, religion, urban residence, employment, family history of abuse, daughter-in-law status and household education, and severity of violence, which were all not significant at p < .05, with the exception of women who were of “other/none” religion who were more likely than Hindu women to seek help from informal sources (OR = 1.7, p = .001). Older women were more likely (OR = 1.05, p = .003) and Muslims were less likely (AOR = 0.24, p = .030) to seek help from institutions. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; OR = odds ratio; IPV = intimate partner violence.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Two of the strongest factors related to help-seeking from informal and formal sources was suffering an injury from the husband's violence (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.80, p < .001 and AOR = 4.38, p < .001, respectively) and severity of the violence. Women whose spouses drink alcohol were also more likely to seek help from informal sources (AOR = 1.38, p < .001).

As for the empowerment measures, there were no significant effects of individual empowerment on help-seeking at (p ≤ .05). A greater spousal age difference was negatively associated with help-seeking from family/friends (AOR = 0.98, p = .003). Women whose spouses exerted a greater number of controlling behaviors were significantly more likely to seek help from both informal and formal sources; the odds increased by 17% and 45%, respectively (p < .001, for both). Joint decision making by the couple was unrelated to seeking informal help, but strongly related to seeking help from the formal sector: Women who participate in decision making had more than 6 times the odds of seeking recourse from an institution (AOR = 8.22, p = .007). Women who reported having money for their own use were no more likely to seek help.

Greater freedom of movement was associated with 7% higher odds of help-seeking from informal (p = .006) and 28% higher odds in the formal sector (p = .015).5

Turning to the state-level measures, tolerance of IPV was related to help-seeking in the informal sector (AOR = 1.22, p = .004). Women in states with higher scores of the GEM had about 23% higher odds of seeking help from informal sources, and 38% lower odds of seeking help from the formal sector (p < .001, for both). However, the GDI was positively related to seeking help from the formal sector (AOR = 1.39, p = .029).

In Table 3, we investigated whether the significant relationship measures of empowerment (identified in Model 2) were moderated by state-level acceptance of wife-beating and the GEM. As specified conceptually in the analytic plan, even though state-level acceptance of IPV was not significant at the α = .05 level in the formal sector, examining moderation may reveal subgroup differences. We found that in states with higher state-level female empowerment, women with greater involvement in spousal decision making were more likely to seek help (AOR = 0.01, p = .039). Interactions of GEM with women's freedom of movement, and GEM with husband's control issues were not significant; interactions with state-level acceptance of wife-beating and the relationship-level measures of empowerment were also not significant.

Table 3.

Results of Interactions of Relation-Level Empowerment Measures and State-Level Characteristics.

| Interaction |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model 3. | AOR | p Value |

| Help from informal sources | ||

| GEM × Educational Attainment | 1.01 | .553 |

| GEM × Age Difference | 0.99 | .108 |

| GEM × Control Issues | 1.02 | .495 |

| GEM × Freedom of Movement | 1.04 | .176 |

| State-Level Tolerance of IPV × Age Difference | 1.00 | .610 |

| State-Level Tolerance of IPV × Control Issues | 1.05 | .080 |

| State-Level Tolerance of IPV × Freedom of Movement | 1.03 | .340 |

| Help from formal sources | ||

| GEM × Control Issues | 1.13 | .186 |

| GEM× Decision Making | 0.01* | .039 |

| State-Level Tolerance of IPV × Control Issues | 1.03 | .720 |

| State-Level Tolerance of IPV × Decision Making | 1.10 | .670 |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; GEM = Gender Empowerment Measure; IPV = intimate partner violence.

p < .05.

aAdjusted for all covariates in Model 2 aside from those shown in the left column.

Finally, we illustrated the differences in the probability of help-seeking based on Model 3 results, which included GEM and decision-making interaction terms. Figure 1 shows the predicted probability for seeking help from informal and formal sources, for the minimum, mean, and maximum levels of selected measures that were significant in the final model. For freedom of movement, women with the highest levels of autonomy were 6% more likely to seek help compared with those with the lowest levels. Women whose husbands exhibited all of the controlling behaviors were about 19% more likely to seek help compared with women whose husbands had only some controlling behaviors. The chart also shows the significant effect of state-level empowerment on seeking help from informal sources, with a nearly 36% difference in help-seeking for states with the highest and lowest scores on the GEM. In contrast, the range of probabilities for seeking help from the formal sector is much smaller and the levels of help-seeking from formal sources are much lower.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of seeking help, by selected characteristics and sector, India, 2005-2006.

Discussion

This is the first national study of the role of individual-, relation-, and state-level female empowerment measures for formal and informal help-seeking in India. Our findings regarding the empowerment measures are mixed and indicate there are limits to which empowerment in any one sphere (e.g., wealth or decision making) transfers to a behavioral action for recourse from abuse. Consistent with other studies from India and other cultures, most women did not seek help and injury was the strongest correlate of help-seeking (Bhatia, 2012; Jayasuriya, Wijewardena, & Axemo, 2011; N. Mitra, 2000; Montalvo-Liendo, 2009; Okenwa, Lawoko, & Jansson, 2009). We note that the measures of empowerment used here may not capture all dimensions of women's empowerment; they reflect some important ones, and show that even empowered women face many barriers to seeking help.

Educational attainment was only marginally related to informal help-seeking (p = .07), and not at all to formal help-seeking, despite the conceptual link that education can promote self-esteem (Mahmud, Shah, & Becker, 2012), agency, and control (Mirowsky & Ross, 1998) or enable women to recognize violence. Qualitative studies from other cultures also suggest education is not strongly associated with seeking help (Okenwa et al., 2009). More work is needed to understand if the benefits of education can facilitate overcoming personal or cognitive barriers, such as fear and stigma that are strong deterrents of seeking help (Coast, Leone, & Malviya, 2012; Dhawan et al., 1999; Montalvo-Liendo, 2009). Concerning wealth, we found no significant relationship with help-seeking, consistent with other studies from India that show that women from wealthier families who experience IPV are the least likely to seek help (Visaria, 2008). Although both income and education wealth may confer resources that can expand women's choices and improve their quality of life, wealthier women may face a greater loss of status, financial problems, and/or threatening repercussions as a consequence of having the problem exposed (Tichy et al., 2009). For example, Mitra and Singh explored the Kerala Paradox, finding that although the state of Kerala has the highest level of human capital development, wealth, and female education, patriarchal norms persist and a higher percentage of women reported tolerance of wife-beating compared with the national average (60.8% compared with 53.3%; A. Mitra & Singh, 2007). Rocca et al. (2009), using a sample of woman from Bangalore, India, found that women who participated in vocational training, employment opportunities, and social groups were more likely to experience domestic violence relative to those who did not. This supports our inference that empowerment without the social acceptance of gender equality can have unintended consequences. An important implication of these findings is that interventions and screening programs should target women from all socio-economic classes.

Autonomy was positively associated with help-seeking in both sectors, whereas decision making was positively related to help-seeking from the formal sector. Findings from our analysis also point to the interaction of person-level and contextual-level factors, whereby tolerance of wife-beating can dampen the positive association of autonomy with help-seeking. Our analysis also relies on a measure of autonomy that reflects only “freedom of movement,” which does not fully capture a woman's ability to act or think independently from social norms or her self-assertion. Although she may have freedom in her movement which could increase her access to help, such help may not be available in contexts where abuse tolerated. Moreover, such environments may limit her cognitive and emotional capacity to engage in seeking change (Pinnewala, 2009). More research is needed to understand the situational factors that diminish a woman's autonomy and what community supports can bolster a woman's autonomy to enable her to seek help. At the same time, though community-based resources for women may facilitate help-seeking, it is also important to reach women who may be suffering but do not have the autonomy to enter the community. Our findings also suggest that medical facilities could be settings for intervention. However, to date, there is little research on how providers identify and assist women in India when they seek help and there is a need for training on assisting victims among health care professionals (Chibber et al., 2011).

We found evidence that state-level indicators of empowerment were positively related to help-seeking, and some evidence that individual aspects of empowerment can be enhanced by state-level factors. This suggests that the social environment is key to help-seeking and improving help-seeking will be supported by efforts to create broad social changes in addition to individual-level interventions. Yet there have been few studies that have quantitatively examined the role of state- or community-level factors in help-seeking, with more attention on characterizing contexts and social norms that tolerate a high prevalence of IPV. Rao (1997) examined three villages in Southern India, and found that community tolerance of wife-beating or community resistance to and resources for victims of violence promoted help-seeking.

Uthman et al. (2011) found that women in communities tolerant of IPV are more likely to experience spousal violence compared with less tolerant communities (Uthman et al., 2011). The findings of the current study support more research aimed at understanding how the cognitive and contextual aspects of empowerment can be realized by a married woman to overcome personal, interpersonal, and social factors that prevent her from seeking help. At the same time, research should also understand men's views on wife-beating and on what factors sustain violence in relationships and in communities. Because the social system interacts with a woman's own capacities, strong advocacy against social norms that condone violence are needed from community and political leaders.

Although not central to the study, it is also noteworthy that the husband's controlling behaviors and alcohol use were related to help-seeking. Controlling behaviors by the husband may be positively related to help-seeking due to the capacity for women to acknowledge their husbands’ behaviors as problematic and seek recourse. Alcohol use may be related to a help-seeking due to particular aspects of the violence and household situation among men (Rao, 1997). These findings point to the need for a stronger focus on targeting men and couples for interventions. Interventions to promote seeking help could screen women about their husbands’ controlling behaviors and alcohol use, and target men on such behaviors. Targeting young men and boys is also important due to the intergenerational nature of domestic violence: young men who witness violent behaviors toward women are more likely to commit partner violence in adulthood (Dalal & Lindqvist, 2012; Koenig et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2002; Reitzel-Jaffe & Wolfe, 2001).

Women who witnessed their father beat their mother were more likely to seek formal help. Research from other cultures suggest that this may be due to the unavailability of the woman's family due to violence and the need to seek outside sources of help (Clark, Silverman, Shahrouri, Everson-Rose, & Groce, 2010; Spencer et al., 2014). Therefore, though most women rely on informal sources for disclosure and help-seeking, the availability of formal sources of assistance is essential for those whose informal options are limited (Spencer et al., 2014). This finding suggests that asking women about witnessing abuse in childhood could be an entry point for health services personnel to start conversations with women around spousal violence.

Injury was one of the strongest predictors of women seeking help, consistent with studies from several other countries and cultures (Fanslow & Robinson, 2009; Fugate, 2005; Zhao & Becker). Qualitative studies indicate that abuse must often be prolonged and has severe physical consequences before women seek help (Naved et al., 2006; Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005). Women in India have acknowledged that the social consequences of drawing attention to abuse can outweigh the physical harm. Such social consequences include fear they may lose their children, be unable to marry in the future, or face blame or retaliation from the community (N. Mitra, 2000). As a result of these barriers, women may view coping, rather than resolving the violence, as the best option (Pinnewala, 2009). Qualitative research is needed to learn more about how women process and cope with violence so that interventions can reach women before injury occurs. However, our finding that throughout India, injury remains more strongly related to seeking help than a woman's personal or relationship factors indicates that marital violence with or without visible injury is a critical public health concern. Injury suffered by these women affects their personal and economic well-being and consequently their children and the household members whom they support. Our finding is consistent with other qualitative and quantitative consistent work, but national in scope and should provide substantial support for action and advocacy among community leaders, public health professionals, and policy makers.

Limitations

We note several limitations. We were not able to include several measures that may affect help-seeking, including the type of marriage (whether dowry was paid or not), how frequently the woman was able to contact kin, or the availability of institutional resources. We are also limited to aggregation at the state level for describing the woman's macro context, as the NFHS-3 does not represent any units of geography below the state level that sufficiently support the estimation of standard errors. Further research could use smaller units of geography to assess the impact of a woman's social context. Others researchers have also been critical of the UNDP GEM as measure of empowerment (Geske Dijkstra, 2006; Syed, 2010). Although the GEM we use here was developed by the GOI, it may still not reflect the ways in which women were empowered at the state level. In addition, our study uses cross-sectional data, which obscures the causal ordering of empowerment, attitudes toward abuse, experiences of violence, and help-seeking behaviors. Due to small sample sizes and limitations in scope, we did not examine women who sought help only from formal sources (n = 58) or help-seeking among unmarried women who experience abuse from their current partners (n = 41); future studies could examine these populations as well. Finally, we are limited in the ability to compare our findings on the association of empowerment with help-seeking in other countries, as little research has explored this relationship.

Conclusion

Together these findings point to the need for societal level interventions. Efforts to enhance empowerment at the individual level may do little to improve help-seeking, as relationship and contextual factors that allow patriarchal notions about gender roles to exist create barriers to recourse. Norms that dictate a husband has control over his wife allow men to justify and women to tolerate abuse. Women in India may come to frame abuse as expected within social norms (Kamat et al., 2013) or as “benevolent guidance” from their husband (Tichy et al., 2009) or a result of their own “mistakes” (Jejeebhoy, 1998; Kapadia-Kundu et al., 2007). They may accept abuse in accordance with the subservient role of women and gender inequality in marriage (Ahmed-Ghosh, 2004; A. Mitra & Singh, 2007; Panda & Agarwal, 2005; Tichy et al., 2009).

Social norms affect not only a woman's decision to seek help, but also the response she receives should she seek it (Dhawan et al., 1999). Policies aimed at changing norms around marital violence and strengthening formal institutional recourse for domestic violence, such as in the legal and health care sectors, are necessary. For example, despite the passing of the 2005 Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act, many women still face financial interpersonal consequences for taking legal action, and less than half of the cases resulted in women obtaining the protective orders they sought (Bhatia, 2012).

Our findings indicate that changes that improve the contextual aspects of women's empowerment can help improve seeking help for spousal abuse. Although policies aimed at empowering women through education and other skills to provide them autonomy and income are important, they will do little to avert their exposure to marital violence. National, state, and local leaders will need to participate in reforms to change institutions that discourage help-seeking, and enact stronger protection, support, and recourse for spousal violence.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Miriam King, Elizabeth Boyle, and the Integrated Demographic and Health Survey Team for their feedback on this study.

Part of the study was completed during Dr. Rowan's graduate assistantship, working on the Integrated Demographic and Health Series (IDHS; NIH Grant 5R01HD069471-03) IDHS data and documentation are disseminated at www.idhsdata.org or available at http://dhsprogram.com/data/

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Biography

Kathleen Rowan, PhD, is a health services researcher at NORC at the University of Chicago, a social science research organization that collects and analyzes data on key social issues. Her research interests include social factors that affect access to mental health care and the design and evaluation of innovations in health care delivery innovations under the Affordable Care Act. She has a background in international health and comparative health systems research.

Elizabeth Mumford, PhD, is a social epidemiologist at NORC at the University of Chicago, a social science research organization that collects and analyzes data on key social issues. Her research includes studies of the epidemiology and prevention of aggressive behavior in intimate partnerships. She also maintains an active research portfolio in tobacco epidemiology and control policies.

Cari Jo Clark, ScD, is an assistant professor in the University of Minnesota Medical School and adjunct assistant professor in the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. She received a U.S. Department of Education Foreign Language and Area Studies Grant and completed her dissertation research in Jordan as a Fulbright Recipient. Her research is focused on the health effects of exposure to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence and the design and evaluation of violence prevention strategies. She has led studies examining the role of violence in the development of obesity and cardiovascular disease and is currently leading a randomized controlled trial of an intervention designed to prevent violence against women and girls in Nepal.

Appendix

Indicators for political participation and decision-making power: (a) percent share of parliamentary seats (elected), (b) percent share of seats in legislature (elected), (c) percent share of seats in zilla parishads (elected), (d) percent share of seats in gram panchayats (elected), (e) percent candidates in electoral process in national parties in the parliamentary election, and (f) percent electors exercising the right to vote in the parliamentary election.

Indicators for economic participation and decision-making power: (a) percent share of officials in service in Indian Administrative Service, Indian Police Service, and Indian Forest Service and (b) percent share of enrollment in medical and engineering colleges.

Indicators for power over economic resources: (a) percent female/male with operational land holdings, (b) percent females/males with bank accounts in scheduled commercial banks (with credit limit above Rs. 2 lakhs), and (c) female/male estimated earned income share.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We also examined analyses using a count of the number scenarios under which the wife expresses conditional tolerance of wife-beating, and the findings were consistent with the dichotomous measure.

Using the partner reported data would limit the sample to women whose partners answered the men's survey.

We also constructed state-level education and wealth variables, but factor analysis indicated that these loaded with Gender Development Index (GDI), so we used a more parsimonious model that included only GDI.

We initially examined the intra-state correlation using multilevel models (unconditional random intercept models) to obtain the intra-class correlation (ICC), or variation due to shared unobserved state-level factors. We found the ICC was about 3%, which is unsubstantial, so we proceeded with models that do not account for this nesting of persons within states. We also tested models with state as a dummy variable and results did not change. We also examined a bivariate probit model that considered selection bias in the sample (only women who were abused were asked about help-seeking); this did not provide a better fit. Rho (ρ) was not significant at .084. Finally, we also estimated for moderate and severe violence separately and found that for a large extent, results were consistent.

We conducted supplemental analyses (not shown in table) and entered each type of autonomy and decision making in the model as binary variables and found that in the formal sector, freedom to go to a market and to a medical facility was associated with help-seeking in the informal sector, whereas going to a medical facility and alone into the community was correlated with formal help-seeking. Each decision measure independently was not associated with help-seeking. In our supplemental analyses, only the measures of freedom to go to a market and to a medical facility were associated with help-seeking in the informal sector, whereas going to a medical facility and alone into the community was associated with formal help-seeking. These types of autonomy may reflect a capacity to interact in social spheres in ways that enhance empowerment to a larger extent than autonomy measured as ability to access health care for herself. Seeking her own health care may be a necessary reason for a woman to leave the household, and less indicative of autonomy.

References

- Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, Devries K, Kiss L, Ellsberg M, Heise L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. Article 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson LK, Subramanian S. State gender inequality, socioeconomic status and intimate partner violence (IPV) in India: A multilevel analysis. Australian Journal of Social Issues. 2008;43:81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: Implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed-Ghosh H. Chattels of society: Domestic violence in India. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:94–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia M. Domestic violence in India: Cases under the protection of women from domestic violence act, 2005. South Asia Research. 2012;32:103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran K. A statistical study on women's perception on violence against women in Puducherry. International Journal of Criminology & Sociological Theory. 2013;6(3):61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chibber KS, Krishnan S, Minkler M. Physician practices in response to intimate partner violence in Southern India: Insights from a qualitative study. Women & Health. 2011;51:168–185. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2010.550993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CJ, Silverman JG, Shahrouri M, Everson-Rose S, Groce N. The role of the extended family in women's risk of intimate partner violence in Jordan. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.024. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coast E, Leone T, Malviya A. Gender-based violence and reproductive health in five Indian states. In: Keerty N, editor. Gender-based violence and public health. Routledge; New York, NY: 2012. pp. 163–183. Available at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/46132/ [Google Scholar]

- Dalal K, Lindqvist K. A national study of the prevalence and correlates of domestic violence among women in India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2012;24:265–277. doi: 10.1177/1010539510384499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Comorbidity between abuse of an adult and DSM-III-R mental disorders: Evidence from an epidemiological study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:131–133. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Andrist L. Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography. 2010;47:667–687. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan N, Punetha D, Sinha Y, Gaur SP, Tyler SL, Tyler FB. Family conflict/violence patterns in India. Psychology and Developing Societies. 1999;11:195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A. Researching domestic violence against women: Methodological and ethical considerations. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanslow J, Robinson E. Help-seeking behaviors and reasons for help seeking reported by representative sample of women victims of intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;(5):929–951. doi: 10.1177/0886260509336963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotso J, Ezeh AC, Essendi H. Maternal health in resource-poor urban settings: How does women's autonomy influence the utilization of obstetric care services. Reproductive Health. 2009;6(9):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugate M, Landis L, Riordan K, Naureckas S, Engel B. Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):290–310. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta M, Salway S. Women's position within the household as a determinant of maternal health care use in Nepal. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2006;32:17–27. doi: 10.1363/3201706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. The Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geske Dijkstra A. Towards a fresh start in measuring gender equality: A contribution to the debate. Journal of Human Development. 2006;7:275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman S. Women's autonomy and child survival: A comparison of Muslims and non-Muslims in four Asian countries. Demography. 2003;40:419–436. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0021. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Johnson SC, Bentley ME, Sivaram S, Srikrishnan A, Celentano DD, Solomon S. Crossing the threshold: Engendered definitions of socially acceptable domestic violence in Chennai, India. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2003;5:393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gubhaju B, Matthews SA. Women's empowerment, sociocultural context, and reproductive behavior in Nepal. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2009;24:25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K, Yesudian PP. Evidence of women's empowerment in India: A study of socio-spatial disparities. GeoJournal. 2006;65:365–380. doi:10.1007/s10708-006-7556-z. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview (Report for the UK Department for International Development) STRIVE Research Consortium, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; London, United Kingdom: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hindin MJ, Kishor S, Ansara DL. Intimate partner violence among couples in 10 DHS countries: Predictors and health outcomes. Macro International, Inc.; Calverton, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences & Macro International . National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India. International Institute for Population Sciences; Mumbai, India: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasuriya V, Wijewardena K, Axemo P. Intimate partner violence against women in the capital province of Sri Lanka: Prevalence, risk factors, and help seeking. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:1086–1102. doi: 10.1177/1077801211417151. doi:10.1177/1077801211417151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ. Wife-beating in rural India: A husband's right? Evidence from survey data. Economic & Political Weekly. 1998;33(15):855–862. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Santhya KG, Sabarwal S. Gender-based violence: A qualitative exploration of norms, experiences and positive deviance. Population Council; New Delhi, India: 2013. Retrieved from http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/pdf/outputs/ORIE/Qualitative_report_Formative_Study_VAWG_Bihar_DFID_India.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women's empowerment. Development and Change. 1999;30:435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kamat US, Ferreira A, Mashelkar K, Pinto NR, Pirankar S. Domestic violence against women in rural Goa (India): Prevalence, determinants and help-seeking behaviour. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research. 2013;3(9):65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura A, Ganta V, Myers K, Thomas T. Intimate partner violence and physical and mental health among women utilizing community health services in Gujarat, India. BMC Women's Health. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-127. Article 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagaratnam P, Mason R, Hyman I, Manuel L, Berman H, Toner B. Burden of womanhood: Tamil women's perceptions of coping with intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:647–658. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9461-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia-Kundu N, Khale M, Upadhaye S, Chavan D. Whose mistake? Gender roles and physical violence among young married women. Economic & Political Weekly. 2007;42(44):71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, Cherukuri S. Domestic violence in India: Insights from the 2005-2006 national family health survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:773–807. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455867. doi:10.1177/0886260512455867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S, Johnson K. Profiling domestic violence: A multi-country study. MEASURE DHS. Macro International Inc.; Calverton, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S, Johnson K. Reproductive health and domestic violence: Are the poorest women uniquely disadvantaged? Demography. 2006;43:293–307. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S, Subaiya L. Understanding women's empowerment: A comparative analysis of demographic and health surveys (DHS) data. Macro International; Calverton, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:132–138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Subbiah K, Khanum S, Chandra PS, Padian NS. An intergenerational women's empowerment intervention to mitigate domestic violence: Results of a pilot study in Bengaluru, India. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:346–370. doi: 10.1177/1077801212442628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, Weintraub S. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:71–84. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud S, Shah NM, Becker S. Measurement of women's empowerment in rural Bangladesh. World Development. 2012;40:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Moracco KE, Garro J, Tsui AO, Kupper LL, Chase JL, Campbell JC. Domestic violence across generations: Findings from Northern India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:560–572. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias SM. Gender, the state and patriarchy: Partner violence in Mexico (ProQuest) University of Texas; Austin: 2008. Unpublished dissertation. Available at https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/3878. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Women & Child Development . Gendering human development indices: Recasting the gender development index and gender empowerment measure for India. Ministry of Women & Child Development, Indian Institute of Public Administration; New Delhi, India: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, personal control, lifestyle and health. Research on Aging. 1998;20:415–449. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A, Singh P. Human capital attainment and gender empowerment: The Kerala paradox. Social Science Quarterly. 2007;88:1227–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra N. Responses to domestic violence in the states of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. International Center for Research on Women; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mogford E. When status hurts: Dimensions of women's status and domestic abuse in rural Northern India. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:835–857. doi: 10.1177/1077801211412545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo-Liendo N. Cross-cultural factors in disclosure of intimate partner violence: An integrated review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:20–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KE, Luchok KJ, Richter DL, Parra-Medina D. Factors influencing help-seeking from informal networks among African American victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1493–1511. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naved RT, Azim S, Bhuiya A, Persson LÅ. Physical violence by husbands: Magnitude, disclosure and help-seeking behavior of women in Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:2917–2929. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okenwa L, Lawoko S, Jansson B. Factors associated with disclosure of intimate partner violence among women in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Injury & Violence Research. 2009;1:37–47. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v1i1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayanju L, Naguib R, Nguyen Q, Bali R, Vung N. Combating intimate partner violence in Africa: Opportunities and challenges in five African countries. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto CC, O'Campo P. Community level effects of gender inequality on intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy in Colombia: Testing the feminist perspective. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:2205–2216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchanadeswaran S, Koverola C. The voices of battered women in India. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:736–758. doi: 10.1177/1077801205276088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda P, Agarwal B. Marital violence, human development and women's property status in India. World Development. 2005;33:823–850. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey G, Dutt D, Banerjee B. Partner and relationship factors in domestic violence perspectives of women from a slum in Calcutta, India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:1175–1191. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburúa E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women's mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women's Health. 2006;15:599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnewala P. Good women, martyrs, and survivors: A theoretical framework for South Asian women's responses to partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:81–105. doi: 10.1177/1077801208328005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: A cross-sectional, observational study. The Lancet. 2009;373:1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randell K, Bledsoe L, Shroff P, Pierce M. Mothers' motivations for intimate partner violence help-seeking. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:55–62. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9401-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rao V. Wife-beating in rural South India: A qualitative and econometric analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44:1169–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wolfe DA. Predictors of relationship abuse among young men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca CH, Rathod S, Falle T, Pande RP, Krishnan S. Challenging assumptions about women's empowerment: Social and economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38:577–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppanner LE. Cross-national reports of housework: An investigation of the gender empowerment measure. Social Science Research. 2010;39:963–975. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E, Williams J. Understanding gender in Africa: Using qualitative methods to enhance DHS analyses of women's empowerment.. Paper prepared for the IUSSP Scientific Panel on Gender; Nairobi, Kenya. 24-26 August 2009.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Badal SH. Men's violence against women in rural Bangladesh: Undermined or exacerbated by microcredit programmes? Development in Practice. 1998;8:148–157. doi: 10.1080/09614529853774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen P. Enhancing women's choices in responding to domestic violence in Calcutta: A comparison of employment and education. The European Journal of Development Research. 1999;11:65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RA, Shahrouri M, Halasa L, Khalaf I, Clark CJ. Women's help seeking for intimate partner violence in Jordan. Health Care for Women International. 2014;35:380–399. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.815755. doi:10.1080/07399332.2013.815755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. StataSE. Author; College Station, TX: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed J. Reconstructing gender empowerment. Women's Studies International Forum. 2010;33:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/1524838013496335. doi:10.1177/ 1524838013496335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichy LL, Becker JV, Sisco MM. The downside of patriarchal benevolence: Ambivalence in addressing domestic violence and socioeconomic considerat ions for women of Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:547–558. [Google Scholar]

- Uthman OA, Moradi T, Lawoko S. Are individual and community acceptance and witnessing of intimate partner violence related to its occurrence? Multilevel structural equation model. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e27738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderEnde KE, Yount KM, Dynes MM, Sibley LM. Community-level correlates of intimate partner violence against women globally: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75:1143–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visaria L. Violence against women in India: Is empowerment a protective factor? Economic & Political Weekly. 2008;43(48):60–66. [Google Scholar]