Summary

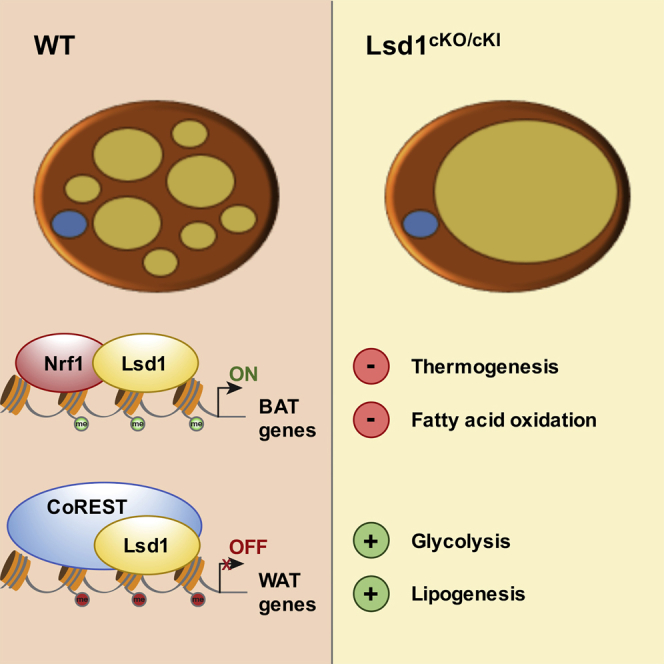

Previous work indicated that lysine-specific demethylase 1 (Lsd1) can positively regulate the oxidative and thermogenic capacities of white and beige adipocytes. Here we investigate the role of Lsd1 in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and find that BAT-selective Lsd1 ablation induces a shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism. This shift is associated with downregulation of BAT-specific and upregulation of white adipose tissue (WAT)-selective gene expression. This results in the accumulation of di- and triacylglycerides and culminates in a profound whitening of BAT in aged Lsd1-deficient mice. Further studies show that Lsd1 maintains BAT properties via a dual role. It activates BAT-selective gene expression in concert with the transcription factor Nrf1 and represses WAT-selective genes through recruitment of the CoREST complex. In conclusion, our data uncover Lsd1 as a key regulator of gene expression and metabolic function in BAT.

Keywords: lysine-specific demethylase 1, brown adipose tissue, epigenetics, lipid metabolism, white adipose tissue, adipocyte, CoREST, thermogenesis, obesity, carbohydrate metabolism

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Loss of Lsd1 in brown adipocytes induces a brown-to-white fat cell conversion

-

•

Lsd1 controls BAT- and WAT-selective genes via a dual mechanism

-

•

Lsd1 deletion in brown adipocytes shifts oxidative to glycolytic metabolism

-

•

Lsd1 controls thermogenesis in BAT to counteract obesity

Duteil et al. find that BAT-selective Lsd1 ablation downregulates BAT-selective and upregulates WAT-selective gene expression. Lsd1 deletion shifts oxidative to glycolytic metabolism, resulting in whitening of BAT. Lsd1 maintains BAT properties in concert with the transcription factor Nrf1 and CoREST.

Introduction

Adipose tissue is an important metabolic regulator of energy balance (Langin, 2010). In mammals, three types of adipose tissues exist. White adipose tissue (WAT) is essentially composed of white adipocytes containing one single large lipid vesicle. WAT is mainly located in the abdominal and subcutaneous areas of the body and is highly adapted to store excess energy in the form of triacylglycerides. Conversely, beige and brown adipocytes are highly energy-expending (Lee et al., 2014a). They are able to dissipate energy in the form of heat via the action of uncoupling protein-1 (Ucp1) (Tiraby and Langin, 2003). Brown adipocytes reside in discrete brown adipose tissue (BAT) depots, such as the interscapular area in rodents, whereas beige adipocytes are intermingled with white adipocytes in WAT. Both brown and beige adipocytes have a multilocular morphology and large numbers of mitochondria and express a common set of brown/beige fat-selective genes, including Ucp1 (Lee et al., 2014b). In rodents, heat generated by brown or beige adipocytes via Ucp1 is essential to survive the cold season (Cohen and Spiegelman, 2015). In both cell types, the cold response is mainly regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, in particular by the β3-adrenergic signaling pathway (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004). In addition to its role in thermogenesis and fatty acid oxidation, it has been reported that BAT activated by the β3-adrenergic signaling pathway can improve glucose homeostasis (Peirce and Vidal-Puig, 2013).

Because recent studies have shown that brown/beige adipocytes exist in quantifiable amounts in humans (Betz and Enerbäck, 2015), these fat types have been rediscovered as potential therapeutic targets for weight loss. Therefore, understanding brown/beige adipocyte function and finding new ways to modulate their activity has become a major scientific point of interest (Betz and Enerbäck, 2015). Among other factors (Harms et al., 2014, Kleiner et al., 2012, Puigserver et al., 1998, Vernochet et al., 2012), the epigenetic regulator lysine-specific demethylase 1 (Lsd1) (Cai et al., 2014, Metzger et al., 2005, Metzger et al., 2016), a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent amine oxidase, has been shown to regulate the differentiation and function of white and beige adipocytes (Duteil et al., 2014, Musri et al., 2010). In WAT, Lsd1 is induced by cold and involved in mediating the effects of β3-adrenergic signaling. Notably, we recently demonstrated that increased expression of Lsd1 in mouse WAT promotes the development of thermogenically active beige adipocytes and suppresses metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (Duteil et al., 2014). Moreover, in mature white adipocytes, elevation of Lsd1 levels is sufficient to activate mitochondria biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and thermogenesis (Duteil et al., 2014). In contrast, the role of Lsd1 in BAT has not been investigated in detail. Brown fat cells exhibit a gene expression profile distinct from either beige or white adipocytes (Wu et al., 2012). Because Lsd1 is a key regulator of metabolism in mature white or beige adipocytes, we asked whether Lsd1 might also play a role in controlling brown adipocyte function.

In this study, we show that selective ablation of Lsd1 or inactivation of its catalytic activity in brown adipocytes triggers a profound whitening of BAT. Lsd1 loss and genetic or chemical inhibition elicits a dramatic rise in expression of WAT-selective genes while impairing the expression of BAT-selective genes. Our data demonstrate that Lsd1 acts via a dual mechanism by positively regulating the expression of BAT-selective genes in cooperation with Nrf1 and actively repressing the expression of WAT-selective genes in concert with the CoREST complex. The whitening of BAT observed upon depletion or inhibition of Lsd1 is accompanied by a shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism associated with an accumulation of di- and triacylglycerides. This collapse of BAT function accelerates body weight gain but improves glucose tolerance. Taken together, our results demonstrate that Lsd1 is essential to maintain the metabolic function of brown adipose tissue.

Results

Lsd1 Represses the White Fat Program in Brown Adipose Tissue

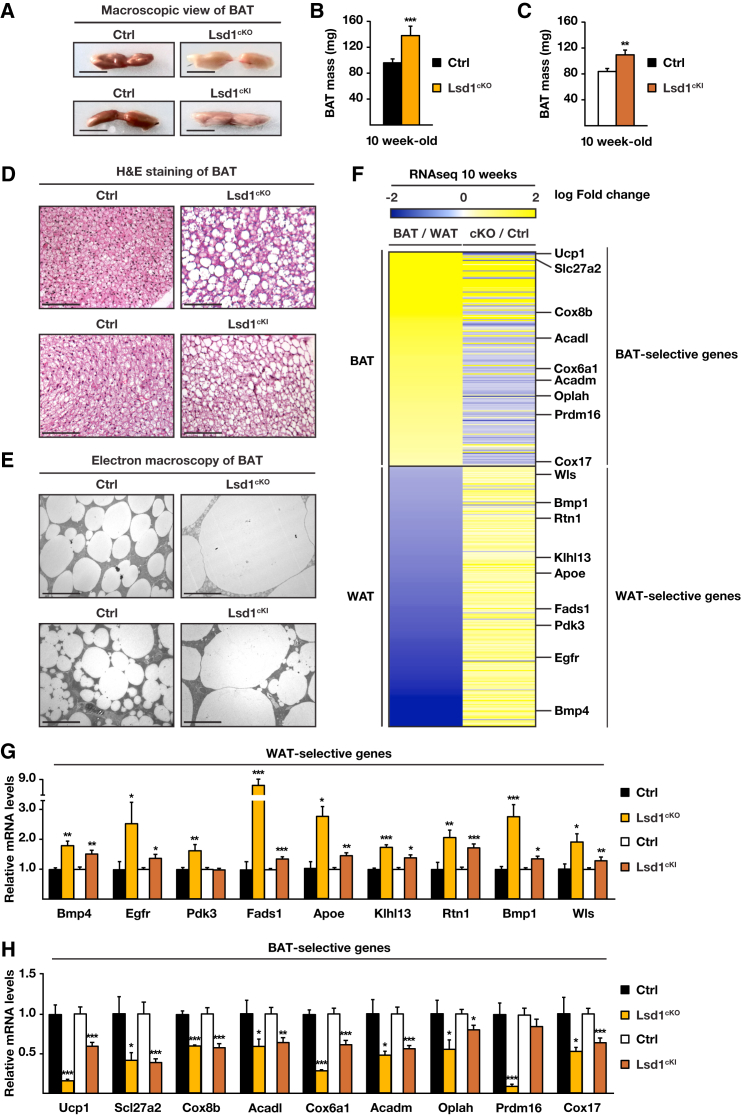

To investigate the role of Lsd1 in BAT, we crossed mice harboring conditional Lsd1 alleles (Zhu et al., 2014) with the Ucp1-Cre deleter strain (Turpin et al., 2014), which resulted in Cre-mediated loss of Lsd1 selectively in brown and beige adipocytes (Lsd1Ucp1-Cre, hereafter named Lsd1cKO) (Figures S1A and S1B). At 10 weeks of age, Lsd1cKO mice exhibited a profound morphological whitening of their BAT (Figure 1A). This whitening was accompanied by an ∼40% increase in tissue mass (Figure 1B), a switch from multilocular to unilocular morphology, and increased lipid content (Figures 1D and 1E). In Lsd1cKO mice, the morphology of mitochondria was severely altered with substantially augmented size and less densely packed cristae (Figure S1C). In accordance, the DNA content of mitochondria was decreased by around 60% in Lsd1cKO mice (Figure S1D), indicating degradation and dysfunction of this organelle. These observations suggested that loss of Lsd1 in brown adipocytes shifted BAT toward a white fat-like phenotype.

Figure 1.

Lsd1 Represses the Expression of WAT-Selective Genes in BAT

(A–E) Macroscopic view (A), mass (B and C), H&E staining (D), and ultrastructure analysis (E) of representative sections of BAT of control (Ctrl), Lsd1cKO, and Lsd1cKI mice.

(B and C) Mean + SEM, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(B) Ctrl, n = 9; Lsd1cKO, n = 7.

(C) Ctrl, n = 7; Lsd1cKI, n = 6.

(F) Heatmap comparing mRNA levels of BAT- and WAT-selective genes in BAT and WAT of control mice (BAT/WAT) and in BAT of Lsd1cKO and control mice (cKO/Ctrl) at 10 weeks of age (Ctrl, n = 4; Lsd1cKO, n = 4).

(G and H) Relative mRNA levels of WAT-selective (G) and BAT-selective (H) genes in BAT of control, Lsd1cKO, and Lsd1cKI mice (mean + SEM, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; Ctrl [black bars], n = 9; Lsd1cKO [orange bars], n = 7; Ctrl [white bars], n = 7; Lsd1cKI [red bars], n = 6).

Scale bars, 5 mm (A), 100 μm (D), 10 μm (E). See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

Accordingly, we expected to see changes in the transcriptional program of brown adipocytes of Lsd1cKO mice that resemble the gene expression profile observed in white adipocytes. We therefore determined the transcriptome of Lsd1-deleted BAT and compared it with the transcriptome of WAT of control mice, which was described previously (Fitzgibbons et al., 2011; Figure 1F; Table S1). The vast majority of WAT-selective genes (95%) was upregulated in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice, whereas 67% of BAT-selective genes showed reduced expression (Figure 1F; Table S1). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that the white fat transcriptome was enhanced to the detriment of the brown fat program, as illustrated by significantly increased expression of representative WAT-selective genes such as Bmp4, Egfr, Pdk3, Fads1, Apoe, Klhl13, Rtn1, Bmp1, and Wls (Figure 1G) and decreased expression of representative BAT-selective genes (Ucp1, Slc27a2, Cox8b, Acadl, Cox6a1, Acadm, Oplah, Prdm16, and Cox17) (Figure 1H) in Lsd1cKO mice. In line with these RNA expression data, western blot analyses showed that BAT of Lsd1cKO mice expressed higher levels of Apoe and reduced levels of Ucp1 protein (Figure S1E). These data suggest that, in BAT, Lsd1 is required to repress the expression of white fat-selective genes while supporting the brown fat-selective gene expression program.

Lsd1 Demethylase Activity Is Required to Maintain the Gene Expression Program of BAT in Mice

To determine whether Lsd1 demethylase activity is required to maintain the brown fat program, we engineered mice homozygous for a conditional, enzymatically inactive mutant Lsd1 knockin allele (Lsd1KI/KI/Ucp1-Cre, hereafter named Lsd1cKI) (Figures S1F–S1I). In BAT of these mice, the endogenous Lsd1 gene is replaced by an enzymatically inactive Lsd1 mutant allele following Ucp1-Cre-mediated recombination. As observed in Lsd1-depleted mice, we found that BAT of Lsd1cKI mice was increased in size and contained a large proportion of unilocular adipocytes (Figures 1A and 1C–1E). Although Lsd1 mRNA levels remained unchanged (Figure S1H), the expression levels of WAT-selective genes were increased, whereas the levels of BAT-selective genes were decreased (Figures 1G and 1H; Figure S1I). In conclusion, alterations in BAT morphology and transcription pattern in Lsd1cKI mice resemble those of Lsd1cKO mice, demonstrating that Lsd1 demethylase activity contributes to the phenotype observed in genetically modified mice.

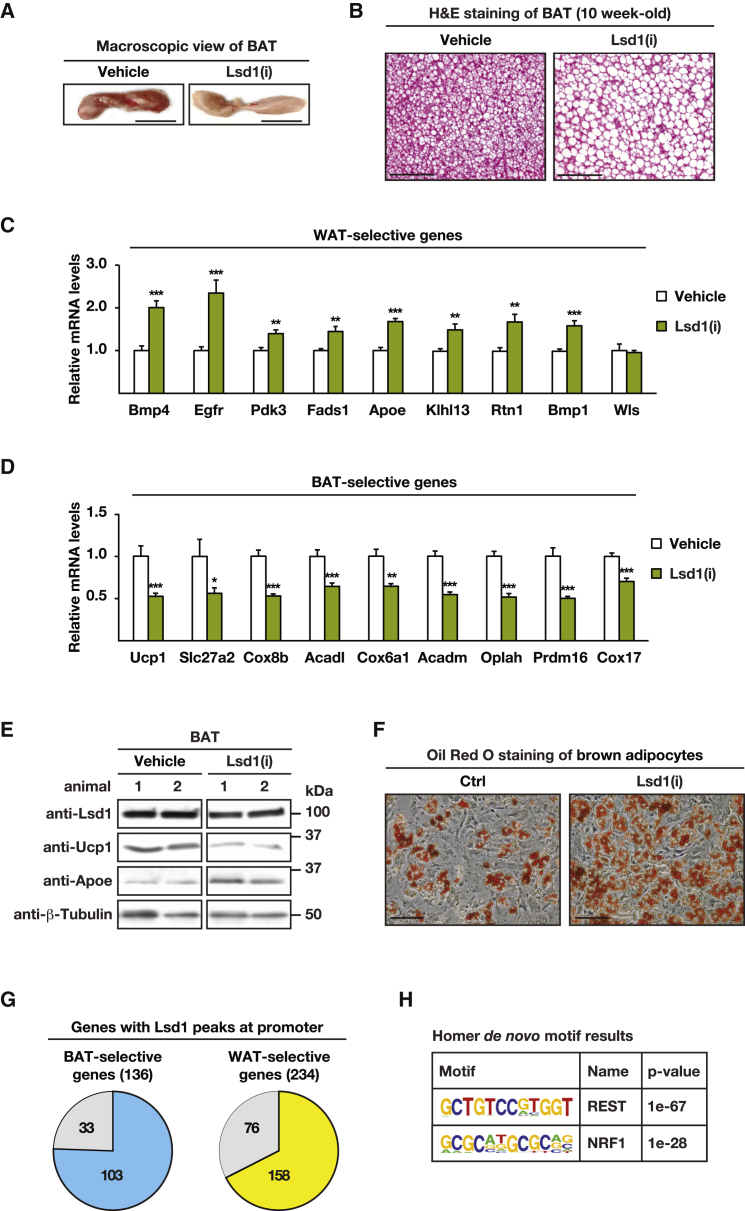

Because the expression of Ucp1 is initiated in utero between embryonic day (E) 18.5 and E19.5, Lsd1 ablation by Ucp1-Cre-mediated recombination is expected to occur around birth (Giralt et al., 1990). To investigate the role of Lsd1 in adult BAT, 10-week-old wild-type mice were treated for 5 days with the Lsd1-specific nanomolar affinity inhibitor QC6688 (Lsd1(i)) or vehicle. BAT of mice treated with Lsd1(i) showed a profoundly pale color and increased size compared with that of vehicle-treated mice (Figure 2A; Figure S2A). H&E staining of BAT sections revealed that Lsd1(i)-treated adipocytes had larger lipid droplets compared with those of vehicle-treated mice (Figure 2B). The expression levels of representative WAT-selective genes were increased at both mRNA and protein levels (Figures 2C and 2E), whereas expression of representative BAT-selective genes was decreased in QC6688-treated mice (Figures 2D and 2E). These data corroborate our findings in Lsd1cKI mice and suggest that catalytically active Lsd1 is required to maintain the metabolic properties of BAT.

Figure 2.

The Demethylase Activity of Lsd1 Is Required to Maintain BAT Properties

(A and B) Macroscopic view (A) and H&E staining (B) of representative sections of BAT of mice treated with vehicle or Lsd1(i).

(C and D) Relative mRNA levels of WAT-selective (C) and BAT-selective (D) genes in BAT of mice treated with vehicle or Lsd1(i) (mean + SEM, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; vehicle, n = 6; Lsd1(i), n = 7).

(E) Western blot analysis of Lsd1, Ucp1, and Apoe in BAT of mice treated with vehicle or Lsd1(i). β-Tubulin was used as a loading control.

(F) Oil red O staining of differentiated primary brown adipocytes treated with vehicle or Lsd1(i).

(G) Pie chart depicting BAT- and WAT-selective genes with Lsd1 peaks at promoters in differentiated primary brown adipocytes.

(H) HOMER motif analysis of Lsd1 ChIP-seq data unraveled Rest and Nrf1 binding sites among the top-scoring motifs.

Scale bars, 5 mm (A), 100 μm (B), 50 μm (F). See also Figure S2.

To investigate the cell autonomy of Lsd1(i) in BAT, we treated differentiated primary brown adipocytes (hereafter named brown adipocytes) isolated from the stromal vascular fraction with Lsd1(i) or vehicle for 3 days. As shown by oil red O staining, Lsd1(i)-treated brown adipocytes accumulated more fat than vehicle-treated cells (Figure 2F) and shifted their transcription pattern to a white adipocyte-like program (Figures S2B–S2D). Together, these data demonstrate that the gene expression program of brown adipocytes is controlled by the catalytic activity of Lsd1 in a cell-autonomous manner.

Lsd1 Has a Dual Role in Controlling Expression of BAT- and WAT-Selective Genes

Next we determined genome-wide Lsd1 chromatin occupancy in brown adipocytes by chromatin immunoprecipitation using Lsd1 antibody followed by massive parallel sequencing (ChIP-seq). The antibody was validated previously and specifically recognizes Lsd1 (Duteil et al., 2014). We found that Lsd1 occupied the promoter of 75% of the BAT-selective genes (103 genes) and 68% of the WAT-selective genes (158 genes) differentially regulated in Lsd1cKO mice (Figure 2G), suggesting a dual mechanism by which Lsd1 represses the expression of WAT-selective genes while activating that of BAT-selective genes.

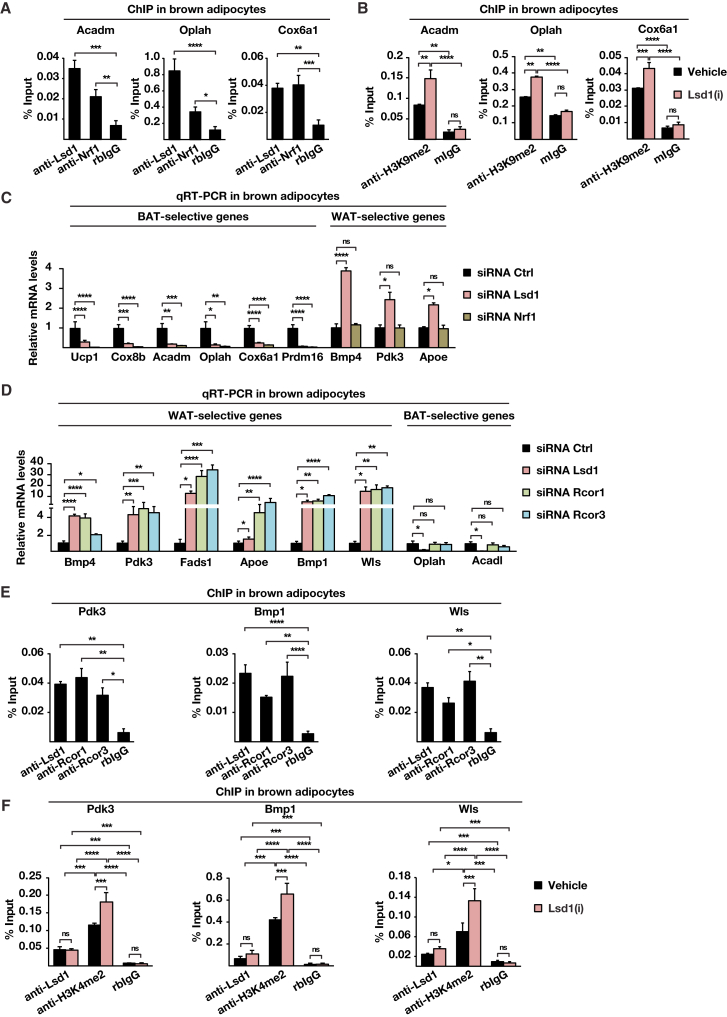

Hypergeometric optimization of motif enrichment (HOMER) motif searches revealed that promoter occupancy of Lsd1 significantly correlated with the presence of binding sites for the transcription factors Nrf1 and Rest (Figure 2H). Thus, we hypothesized that Lsd1 might positively regulate BAT-selective genes in cooperation with Nrf1 while repressing WAT-selective gene expression in concert with the CoREST complex. ChIP with Nrf1 antibody followed by qPCR analysis in brown adipocytes showed that Lsd1 and Nrf1 co-localized at promoters of representative BAT-selective genes such as Acadm, Oplah, and Cox6a1 (Figure 3A). Ucp1 was not part of the analysis because our genome-wide cistrome analysis by ChIP-seq showed no Lsd1 occupancy. Importantly, Nrf1 was not present at the promoter of WAT-selective genes, as illustrated by Figure S3A. Because Lsd1 is known to activate gene expression by erasing dimethyl groups at lysine 9 of histone 3 (H3K9me2), we hypothesized that inhibition of Lsd1 would modify methylation levels of H3K9 at BAT-selective genes. ChIP-qPCR analysis for H3K9me2 revealed that levels of H3K9me2 were increased upon Lsd1(i) treatment at promoters of BAT-selective genes (Figure 3B). In parallel, levels of H3K4me2 were reduced in Lsd1(i)-treated cells (Figure S3B), indicating a repressive transcriptional context. To investigate whether Lsd1 and Nrf1 are present in the same protein complex, nuclear extracts from brown adipocytes were subjected to size exclusion chromatography. Western blot analysis showed that Lsd1 and Nrf1 co-fractionate, suggesting the existence of an Nrf1/Lsd1complex (Figure S3C). Furthermore, Lsd1 and Nrf1 co-immunoprecipitated, confirming interaction between these two endogenously expressed proteins in BAT (Figure S3D). Accordingly, small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of Nrf1 (Figure S3E) significantly decreased transcript levels of BAT-selective genes but did not impair WAT-selective gene expression (Figure 3C). Together, these data demonstrate that Lsd1 controls the expression of BAT-selective genes in cooperation with Nrf1 by targeting H3K9 methylation levels.

Figure 3.

Lsd1 Regulates the Brown Fat Program through a Dual Mechanism

(A and B) ChIP analysis to detect promoter occupancy performed with anti-Lsd1 and anti-Nrf1 antibodies or rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (rbIgG) in wild-type brown adipocytes (A) and anti-H3K9me2 antibody or mouse IgG (mIgG) in brown adipocytes treated with Lsd1(i) or vehicle (B). The precipitated chromatin was quantified by qPCR analysis with primers flanking Lsd1-binding sites in the indicated genes.

(C and D) Relative mRNA levels of the indicated BAT- or WAT-selective genes in brown adipocytes transfected with unrelated control siRNA (siRNA Ctrl) or siRNA directed against Lsd1 (siRNA Lsd1) or Nrf1 (siRNA Nrf1) (C) and with siRNA Ctrl or siRNA directed against Rcor1 (siRNA Rcor1) or Rcor3 (siRNA Rcor3) (D).

(E and F) ChIP analysis to detect promoter occupancy performed with anti-Lsd1, anti-Rcor1, and anti-Rcor3 antibodies or rbIgG in brown adipocytes (E) and anti-Lsd1 and anti-H3K4me2 antibody or rbIgG in brown adipocytes treated with Lsd1(i) or vehicle (F). The precipitated chromatin was quantified by qPCR analysis with primers flanking Lsd1-binding sites in the indicated genes

Data are mean + SEM. (A), (C), (D), and (E): one-way ANOVA. (B) and (F): two-way ANOVA; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; n = 3; qPCRs were run in triplicate. See also Figure S3 and Tables S2, S4, and S5.

Next we analyzed whether an Lsd1-associated repressor complex might regulate the WAT-selective gene program in BAT. For this purpose, nuclear protein extracts from BAT were used for immunoprecipitation with three distinct anti-Lsd1 antibodies directed against various Lsd1 domains followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The intersection of the three interactomes uncovered 163 proteins commonly interacting with Lsd1 (Figure S3F) and revealed the repressive CoREST complex as a significantly enriched protein group (Table S2). Interaction between Lsd1 and CoREST has already been well established (Lee et al., 2005, Metzger et al., 2005, Shi et al., 2004). Accordingly, co-immunoprecipitation experiments and size exclusion chromatography demonstrated that, also in BAT, endogenous Lsd1 interacts with members of the CoREST complex (Figures S3G and S3H). To test whether the CoREST complex indeed represses the expression of WAT-selective genes, we knocked down the complex members Rcor1 and Rcor3 in brown adipocytes (Figure S3I). Cells treated with Rcor1 or Rcor3 siRNA upregulated WAT-selective genes (Figure 3D) without affecting BAT-selective genes, as exemplified by Oplah and Acadl (Figure 3D), and accumulated more lipids than cells treated with control siRNA (Figure S3J). In addition, ChIP-qPCR analyses confirmed the colocalization of Rcor1 and Rcor3 with Lsd1 specifically at promoters of WAT-selective genes (Figure 3E) but not at promoters of BAT-selective genes (Figure S3K). Because Lsd1 is known to repress gene expression by erasing dimethylation of lysine 4 of histone 3 (H3K4me2), we analyzed whether inhibition of Lsd1 is sufficient to alter methylation levels of H3K4 at WAT-selective genes. ChIP-qPCR analysis showed that levels of H3K4me2 were increased upon Lsd1(i) treatment at promoters of WAT-selective genes (Figure 3F). Concomitantly, levels of H3K9me2 were decreased at these promoters (Figure S3L), indicating an active transcriptional context. Together, our data demonstrate that Lsd1 represses WAT-selective gene expression in cooperation with the CoREST complex in BAT by reciprocal modulation of H3K4 and H3K9 methylation levels.

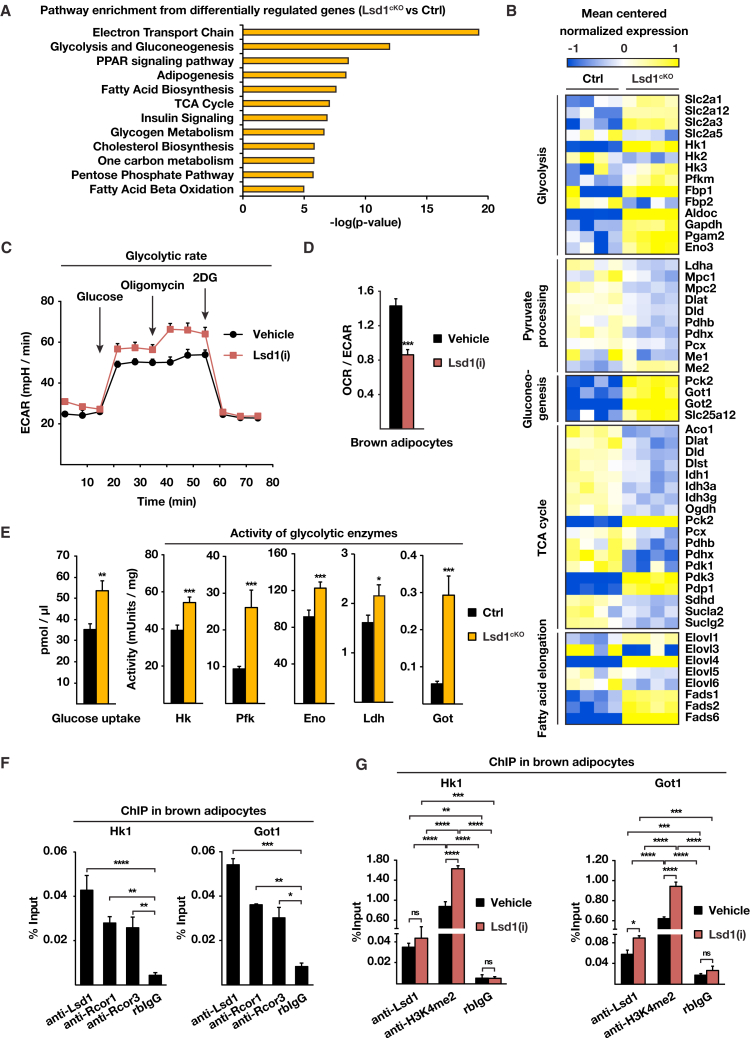

Loss of Lsd1 Induces Glycolysis while Repressing Oxidative Metabolism in BAT

Lsd1cKO mice exhibit a profound morphological whitening of BAT associated with large lipid accumulation. To identify further changes in global gene expression in Lsd1cKO mice that might account for the observed whitening of Lsd1-depleted brown fat, we performed a pathway enrichment analysis of the transcriptome data. The analysis (Figure 4A) uncovered pathways regulating energy production and fatty acid catabolism such as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, electron transport chain (ETC), and β-oxidation. The expression of genes representing these pathways was downregulated (Figure 4B; Figure S4A), suggesting that oxidative metabolism is lowered in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice, confirming our data in WAT (Duteil et al., 2014). Interestingly, the second most enriched pathway was “glycolysis and gluconeogenesis,” which we did not observe in WAT. In line with these findings, we observed increased expression of glucose transporters and the majority of glycolytic enzymes catalyzing glucose-to-pyruvate conversion in Lsd1cKO mice (Figure 4B; Figure S4B). We thus hypothesized that Lsd1 deficiency in BAT not only leads to reduction of oxidative functions but also increases glycolytic capacities. To evaluate bioenergetic changes upon inhibition of Lsd1, we employed a Seahorse XF analyzer (Agilent Technologies) to measure the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as an index of glycolytic activity (using a glycolysis stress kit) and the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) as an index of respiratory capacity (using the Cell Mito stress test kit) in brown adipocytes treated with Lsd1(i) or vehicle. The rate of glycolysis following glucose administration was higher upon Lsd1(i) treatment compared with vehicle (Figure 4C; Figure S4C). After addition of oligomycin, an inhibitor of mitochondrial ATP synthesis, the maximum glycolytic capacity of Lsd1(i)-treated cells remained higher than in control cells, demonstrating that not only the rate of glycolysis but also the glycolytic reserve capacity were enhanced in Lsd1-inactivated cells (Figure 4C; Figure S4C). In parallel, the OCR was lower in Lsd(i)-treated cells compared with vehicle (Figures S4D and S4E), and, subsequently, the OCR/ECAR ratio was decreased, demonstrating that Lsd1 inhibition shifted mitochondrial metabolism toward the glycolytic pathway in brown adipocytes (Figure 4D). Furthermore, oxygen consumption resulting from mitochondrial respiration measured in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice was reduced compared with control mice, confirming lower oxidative phosphorylation (Figure S4F). Taken together, our data show that glycolytic activity is enhanced in the absence of Lsd1, whereas oxidative phosphorylation is reduced.

Figure 4.

Lsd1 Represses Glycolysis in BAT

(A) Enriched pathways obtained from gene ontology (GO) term analysis for genes differentially expressed in BAT of Lsd1cKO and control mice.

(B) Heatmaps depicting mean centered normalized mRNA expression of selected genes involved in the TCA cycle, fatty acid elongation, glycolysis, pyruvate processing, and gluconeogenesis in BAT of Ctrl and Lsd1cKO mice at 10 weeks of age (Ctrl, n = 4; Lsd1cKO, n = 4).

(C and D) Representative ECAR (C) and OCR divided by ECAR (D) for Lsd1(i)- or vehicle-treated brown adipocytes determined with the Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer (mean + SEM, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n = 6).

(E) Determination of glucose uptake, Hk, Pfk, Eno, Ldh, and Got activities in BAT of Ctrl and Lsd1cKO mice at 10 weeks of age (mean + SEM, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n = 5).

(F and G) ChIP analysis to detect promoter occupancy performed with anti-Lsd1, anti-Rcor1, and anti-Rcor3 antibodies or rbIgG in brown adipocytes (F) and anti-Lsd1 and anti-H3K4me2 antibody or rbIgG in brown adipocytes (G) treated with vehicle or Lsd1(i). The precipitated chromatin was quantified by qPCR analysis with primers flanking Lsd1-binding sites in the indicated genes (mean + SEM). (F): one-way ANOVA. (G): two-way ANOVA. ns: p > 0.05, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; n = 3; qPCRs were run in triplicate).

See also Figure S4.

In addition, glucose uptake and activity of key glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase (Hk), phosphofructokinase (Pfk), enolase (Eno), and lactate dehydrogenase (Ldh) were higher in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice compared with control mice (Figure 4E), promoting increased glycolytic capacity.

Of note, the expression levels of genes involved in pyruvate metabolism, including the rate-limiting mitochondrial pyruvate transporters (Mpc1 and Mpc2) and enzymes catalyzing the conversion from pyruvate to acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) (e.g., Dlat and Pdhx), were decreased in Lsd1cKO mice (Figure 4B; Figure S4G). Our genome-wide analysis also revealed that expression of glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1 (Got1) and 2 (Got2) as well as Slc25a12 and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 (Pck2) was upregulated in Lsd1cKO mice compared with control (Figure 4B; Figure S4G). Got1 and 2 are responsible for conversion of downstream pyruvate intermediate oxaloacetate into aspartate and phosphoenolpyruvate, respectively (Birsoy et al., 2015). In particular, Got1 was shown to be essential for aspartate regeneration to restore ETC dysfunction (Birsoy et al., 2015). ETC dysfunction is associated with a drop in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)/NADH ratio because NAD+ cannot be oxidized by complex I. However, despite decreased oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), the NAD+/NADH ratio was increased in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice (Figure S4H). This might be, at least in part, mediated by higher Got1 activity (Figure 4E). An Increased NAD+/NADH ratio is also in favor of increased glycolysis (Zhang et al., 2007).

Similarly, expression profiling of metabolic genes in Lsd1cKI mice and mice treated with Lsd1(i) revealed that Lsd1 demethylase activity strongly contributes to maintaining proper energy metabolism in BAT (Figures S4B, S4G, and S4I). Taken together, these data show that glycolysis is enhanced in Lsd1-inactivated BAT, whereas oxidative metabolism is lowered.

The analysis of genome-wide Lsd1 chromatin occupancy in BAT by ChIP-seq revealed that glucose transporters and genes involved in glycolysis are direct targets of Lsd1 (Figure S4J). ChIP-qPCR of brown adipocytes showed promoter occupancy of representative genes by Rcor1, Rcor3, and Lsd1 (Figure 4F). In parallel, the levels of H3K4me2 were enriched, whereas the levels of H3K9me2 were lowered upon Lsd1(i) treatment (Figure 4G; Figures S4K and S4L). These results demonstrate that Lsd1 is directly repressing glycolytic genes to ensure physiological metabolic processes in brown adipocytes.

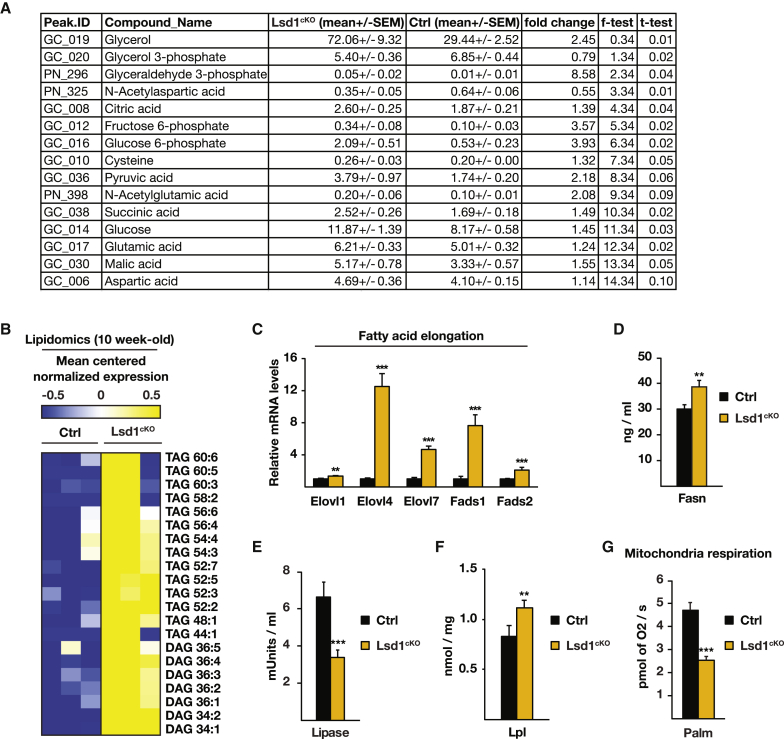

Lsd1 Regulates Lipid Accumulation in BAT

To further investigate our phenotype, we performed metabolomic and lipidomic analyses of BAT of 10-week-old control and Lsd1cKO mice. These analyses revealed an accumulation of intermediates of glycolysis, including glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and glycerol, in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice (Figure 5A) accompanied by augmentation of long-chain diacyl- and triacylglycerides (DAGs and TAGs, respectively) (Figure 5B). In accordance with an increase in long-chain fatty acids, the transcript levels of fatty acid elongases (Elovl1, Elovl4, and Elovl7) and fatty acid desaturases (Fads1 and Fads2) were upregulated in the absence of Lsd1 (Figures 4B and 5C) or Lsd1 demethylase activity (Figures S5A and S5B). The analysis of genome-wide Lsd1 chromatin occupancy in BAT by ChIP-seq revealed that genes encoding enzymes involved in fatty acid elongation are direct targets of Lsd1 (Figures S5C–S5F).

Figure 5.

Lsd1 Limits Fat Accumulation in BAT

(A) Metabolomic analysis of BAT of control and Lsd1cKO mice.

(B) Lipidomic analysis of BAT from 10-week-old control and Lsd1cKO mice.

(C) Relative mRNA levels of the indicated enzymes involved in fatty acid elongation in BAT of control and Lsd1cKO mice (mean + SEM; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; Ctrl, n = 9; Lsd1cKO, n = 7).

(D–F) Determination of fatty acid synthase (Fasn), lipase, and Lpl activities in BAT of Ctrl and Lsd1cKO mice at 10 weeks of age (mean + SEM, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n = 6).

(G) Mitochondrial respiration of BAT extracts from Ctrl and Lsd1cKO mice assessed with a high-resolution respiratory Oxygraph-2K system using palmitoyl-L-carnitine as substrate (mean + SEM, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n = 6).

DAG and TAG are glycerol esters derived from dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and fatty acids. Allocation of fatty acids necessary for glyceride synthesis might be due to decreased lipolysis, increased de novo lipogenesis, or increased fatty acid uptake in BAT of Lsd1cKO mice. Increased fatty acid synthase (Fasn) activity (Figure 5D) and low acetyl-CoA carboxylase phosphorylation (Figure S5G) are in favor of enhanced de novo lipogenesis in Lsd1cKO mice. To assess lipolysis efficiency, we measured lipase activity. The activity of lipases present in brown adipocytes was reduced by 50% in Lsd1cKO mice, suggesting that hydrolysis of lipids into fatty acids is severely impaired (Figure 5E). In addition, the activity of lipoprotein lipase (Lpl), which hydrolyzes triglycerides in lipoproteins such as those found in chylomicrons and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) to facilitate fatty acid uptake from the bloodstream, was increased upon loss of Lsd1 (Figure 5F). Finally, to test whether fatty acid oxidation was altered, we measured mitochondrial respiration in the presence of palmitoyl-L-carnitine as substrate in saponine-permeabilized BAT. The data revealed that Lsd1-deficient BAT failed to properly use fatty acids (Figure 5G). Increased fatty acid synthesis and lower lipolysis are in agreement with the observation of an increased NAD+/NADH ratio (Figure S4H). Altogether, these findings show that Lsd1 regulates lipid accumulation in BAT.

In summary, our data show that Lsd1 positively regulates the expression of oxidative metabolism-related genes with concomitant repression of the gene program responsible for glycolysis and fatty acid biosynthesis. Accordingly, loss of Lsd1 in brown adipose tissue drives a shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism accompanied by aberrant triglyceride accumulation.

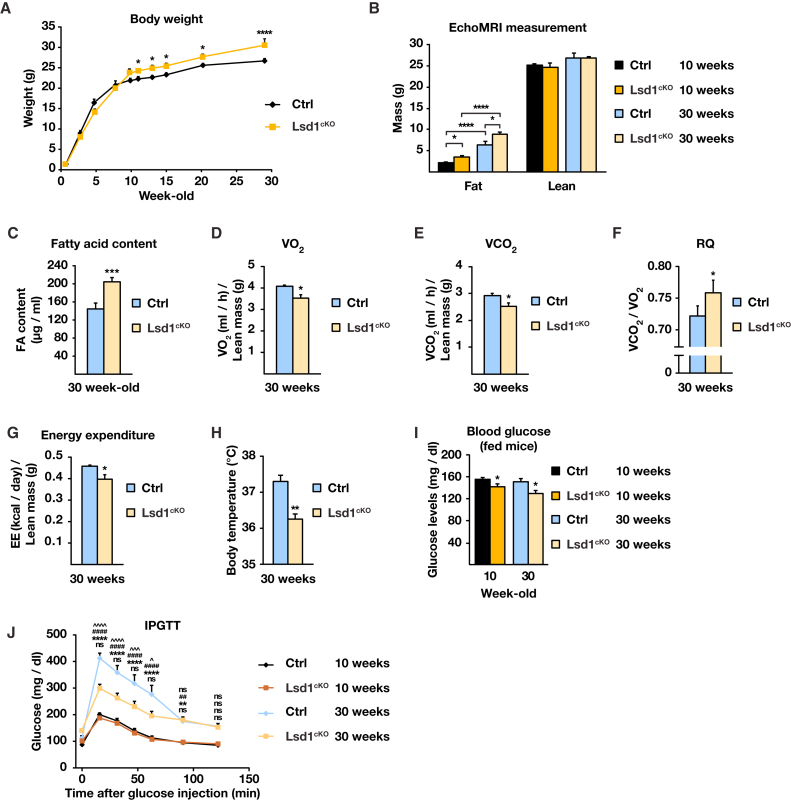

Absence of Lsd1 Improves Glucose Uptake Despite Increasing Body Weight

Finally, we examined the consequences of Lsd1 loss in BAT with aging. Lsd1cKO male mice gained significantly more weight (∼40%) than their control littermates between 10 and 30 weeks of age (Figure 6A). No weight differences were observed in females (Figure S6A). The weight gain of Lsd1cKO mice was not due to increased food intake or decreased mobility (Figures S6B–S6D). Body composition analysis assessed with a whole-body magnetic resonance analyzer (EchoMRI) revealed that 30-week-old Lsd1cKO mice accumulated more fat than their control littermates, resulting in a lower lean/fat mass ratio compared with control mice (Figure 6B). These data were corroborated by a dramatically increased BAT mass in 30-week-old Lsd1cKO mice as well as in Lsd1cKI mice (Figures S6E and S6F), associated with ∼45% augmentation in fatty acid content of BAT (Figure 6C). In accordance, histological analyses revealed a robust phenotypic conversion of BAT in Lsd1cKO and Lsd1cKI mice to a WAT-like appearance (Figure S6G). In addition, we noticed robustly reduced Ucp1 protein levels, as shown by immunocytochemistry (Figure S6G). Observed morphological changes in BAT are accompanied by increased levels of intermediates of glycolysis, glycerol, DAG, and TAG (Figures S6H and S6I).

Figure 6.

Lsd1cKO Mice Have Higher Glucose Uptake Despite Increased Body Weight

(A) Body weight of control and Lsd1cKO mice at the indicated age (mean + SEM; two-way ANOVA with repeated measures; factor interaction, pgenotype/time < 0.0001; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; n = 7).

(B and C) Body fat and lean content(B) and fatty acid content (C) of 30-week-old control and Lsd1cKO mice. (B) and (C): mean + SEM, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. (B): two-way ANOVA, n = 7. (C): n = 5.

(D–G) VO2 (D), VCO2 (E), RQ (F), and energy expenditure (G) of 30-week-old control and Lsd1cKO mice (mean + SEM; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01; Ctrl, n = 8; Lsd1cKO, n = 7). VO2, VCO2, and energy expenditure are normalized to the lean mass.

(H) Body temperature of 30-week-old control and Lsd1cKO mice (mean + SEM; ∗∗p < 0.01; Ctrl, n = 8; Lsd1cKO, n = 7).

(I) Serum glucose levels of fed Ctrl and Lsd1cKO mice at the indicated ages (mean + SEM; ∗p < 0.05; Ctrl, n = 8; Lsd1cKO, n = 7).

(J) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) for 10-week-old or 30-week-old control and Lsd1cKO mice starved for 6 hr prior to analysis (mean + SEM; two-way ANOVA; Ctrl 10-week-old versus Lsd1cKO 10-week-old, ns p > 0.05; Ctrl 10-week-old versus Ctrl 30-week-old, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; Lsd1cKO 10-week-old versus Lsd1cKO 30-week-old, ##p < 0.01, ####p < 0.0001; Ctrl 30-week-old versus Lsd1cKO 30-week-old, ns p > 0.05, ˆp < 0.05, ˆˆˆp < 0.001, ˆˆˆˆp < 0.0001; Ctrl, n = 8; Lsd1cKO, n = 7).

See also Figure S6.

In 30-week-old Lsd1cKO mice, we observed lower energy expenditure, determined by decreased whole-body oxygen consumption (VO2) (Figure 6D; Figures S6J and S6K) and CO2 production (VCO2) (Figure 6E; Figures S6L and S6M), resulting in an increased respiratory quotient (RQ, VCO2/VO2 ratio) (Figure 6F). This confirmed a shift in fuel consumption from fatty acids to carbohydrates. In addition, calorimetric parameters deduced from these analyses indicated that energy expenditure was decreased in Lsd1cKO mice (Figure 6G; Figures S6N and S6O). This was confirmed by body temperature measurements (Figure 6H).

Next we analyzed mice for glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. We observed that circulating glucose levels in 10-week-old Lsd1cKO mice were lower compared with control littermates (Figure 6I). Nevertheless, we did not notice any difference in glucose tolerance of Lsd1cKO mice relative to control mice at this age (Figure 6J). Importantly, with aging, control mice developed progressive glucose intolerance, contrary to Lsd1cKO mice, which conserved efficient glucose uptake (Figure 6J). Age-developed glucose intolerance is generally associated with loss of insulin sensitivity and contributes to type 2 diabetes. To unravel whether Lsd1cKO mice are resistant to age-induced type 2 diabetes, we performed an intraperitoneal insulin sensitivity test (IPIST) and determined serum insulin levels. Despite dramatic alterations in glucose metabolism, we did not observe any difference in insulin sensitivity (Figure S6P) or in total insulin levels (Figure S6Q), showing that only glucose but not insulin metabolism is altered in Lsd1cKO mice. In summary, these data show that Lsd1 is required in BAT to maintain a proper energy balance with aging.

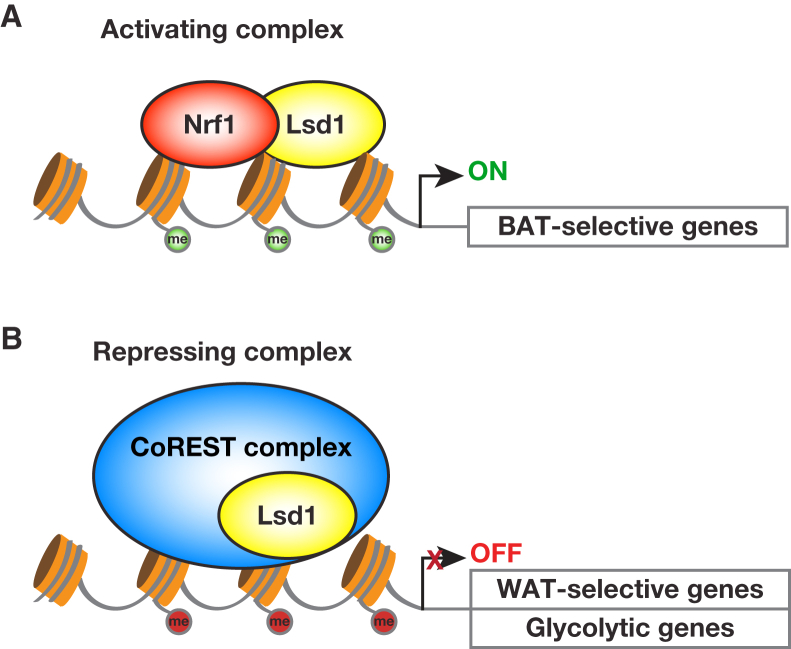

Discussion

White and brown adipocytes have distinct transcriptional programs that facilitate long-term lipid storage or thermogenesis, respectively. Understanding these programs is of the highest interest for developing new strategies to counteract obesity. The epigenetic determinants that regulate white versus brown fat-selective gene expression have not yet been completely elucidated. In this study, we show that the histone demethylase Lsd1 plays a key role in the maintenance of brown fat metabolic properties. Lsd1 accomplishes this mission via a dual mechanism by inhibiting the expression of WAT-selective genes and simultaneously promoting the expression of BAT-selective genes. These opposing functions of Lsd1 are orchestrated by the assembly in different protein complexes: a repressive CoREST complex to inhibit the expression of WAT-selective genes and an Nrf1-containing complex to promote the expression of BAT-selective genes (Figure 7). Our data point out the importance of Lsd1 demethylase activity in controlling BAT metabolism in vivo. Indeed, our engineered mouse model, Lsd1cKI mice, as well as wild-type mice treated with an Lsd1-specific inhibitor, basically recapitulate the phenotype observed in Lsd1cKO mice. Alterations in BAT morphology and transcriptome in Lsd1cKI and Lsd(i)-treated mice resemble that of Lsd1cKO mice and suggest that catalytically active Lsd1 significantly contributes to the maintenance of the BAT gene expression program and function. However, additional scaffolding functions of Lsd1, which might be independent of the enzymatic activity (i.e., the recruitment of proteins and/or the assembly in different protein complexes) might be impaired upon loss of Lsd1 in Lsd1cKO mice. In contrast, in knockin mice, the enzymatically inactive Lsd1 mutant protein might be able to perform, at least in part, these functions, which might explain a less severe phenotype.

Figure 7.

Lsd1 Governs the Gene Expression Program and Metabolic Functions of Brown Adipose Tissue

Lsd1 controls the properties of BAT via a dual mechanism, resulting in inhibition of WAT-selective and promotion of BAT-selective gene expression. This opposing function of Lsd1 is orchestrated via interaction with (A) the activating transcription factor Nrf1 (H3K4me2 marks are depicted in green) and (B) an Lsd1-containing repressive CoREST complex (H3K9me2 marks are depicted in red).

Lsd1 exerts its function in brown adipocytes by engaging in different protein complexes. Coordinated action of Lsd1 with members of the CoREST complex, in particular Rcor1 and Rcor3, represses the expression of WAT-selective genes. Although Lsd1 has been shown to interact with CoREST in various tissues (Lee et al., 2005, Metzger et al., 2005, Shi et al., 2004, Yang et al., 2011), the physiological function of CoREST in vivo remains unclear. Here we demonstrate for the time that the CoREST complex plays a critical role in the repression of the WAT-selective genes in BAT, thereby strongly contributing to the maintenance of brown fat characteristics. In BAT, Lsd1 specifically associates with Rcor1 and Rcor3 but not Rcor2. Similar to Lsd1, Rcor1 is ubiquitously expressed in somatic cells, whereas the expression of Rcor2 and Rcor3 seems to be more restricted (Yang et al., 2011). This suggests that the Lsd1 corepressor complex might assemble with different Rcor family members to carry out specific functions in different cell types.

Furthermore, Lsd1 interacts with Nrf1 to activate the expression of BAT-selective genes. We have shown previously that, in WAT, Lsd1 acts together with Nrf1 to positively regulate OXPHOS and thermogenesis (Duteil et al., 2014). Elevated Lsd1 levels favor beigening of WAT by increasing oxidative metabolism, uncoupling, thermogenesis, and the number and size of mitochondria. Our data provide evidence that the absence of Lsd1 in BAT causes dramatic mitochondrial dysfunction associated with decreased transcript levels of OXPHOS-related genes. It is interesting that Lsd1 in cooperation with Nrf1 shares comparable functions in beige and brown adipocytes. Whether the mechanism of regulation of oxidative metabolism is conserved in all metabolically active tissues remains unclear. To clarify this hypothesis, it would be necessary to analyze the metabolism of skeletal muscle and liver in Lsd1 knockout mice.

Our analyses uncovered that Lsd1 is necessary to regulate metabolism, particularly fatty acid oxidation, de novo lipogenesis, and lipolysis, leading to increased DAG and TAG accumulation and whitening of Lsd1cKO BAT. In addition, Lsd1 depletion/inhibition leads to elevated glucose uptake and increased glycolytic capacities in mice. This may contribute to DAG and TAG accumulation because the glycerol backbone for triglyceride synthesis can be derived from the glycolytic intermediate dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Furthermore, pyruvate is converted into citrate in the TCA cycle and utilized to provide acetyl-CoA to initiate de novo lipogenesis. However, further experiments would be necessary to provide a direct link between these processes. Nevertheless, the role of Lsd1 in lipid metabolism has been confirmed in this study because Lsd1cKO mice show increased activity of fatty acid synthase and decreased activity of lipases. Altogether, alterations in glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation might contribute to aberrant production of DAG and TAG, which leads to increased fat accumulation.

Transcriptional and metabolic changes induced by Lsd1 ablation have secondary effects on body weight gain and glucose tolerance with aging. Indeed, Lsd1cKO mice gained significantly more weight than their control littermates. These findings are of interest, considering that many mouse models possessing defects in adipose tissue function and metabolism, such as loss of mitochondrial uncoupling (Liu et al., 2003) and fatty acid or ceramide metabolism (Ellis et al., 2010, Lee et al., 2016, Schoiswohl et al., 2015, Turpin et al., 2014), do not develop obesity. A hypothesis might be that Lsd1-deficient brown adipocytes secrete signaling molecules that exert a potential inhibitory function on energy expenditure in other metabolic organs such as white adipose tissue, liver, or muscle. Consequently, we carefully inspected our transcriptome analysis for differential expression of endocrine molecules, cytokines, or other signaling molecules. This analysis failed to identify any known candidates that might explain the phenotype in our mice. This, however, does not exclude the possibility that Lsd1 regulates the expression of yet undescribed endocrine molecules in brown adipocytes. Future studies will be required to elucidate this issue.

Previous studies showed that the ablation of the brown fat-determining transcriptional regulator Prdm16 is required to suppress the expression of WAT-selective genes in BAT (Harms et al., 2014) similar to Lsd1. However, the expression of the most typical BAT-selective genes was only slightly reduced upon Prdm16 ablation, which could explain why Prdm16 knockout mice are not prone to obesity (Harms et al., 2014). In line with this publication, Zeng et al. (2016) showed that Lsd1 associates with Prdm16 to repress expression of WAT-selective genes. Of note, our ChIP-seq data identified Prdm16 as a direct Lsd1 target, and Prdm16 expression was reduced in Lsd1-deleted BAT. However, immunoprecipitation, size exclusion chromatography, and mass spectrometry analyses did not provide any evidence for association of Lsd1 and Prdm16 in BAT, suggesting that Lsd1 acts upstream of Prdm16. Zeng et al. (2016) also claim that Lsd1 represses the expression of hydroxysteroid 11-β-dehydrogenase isozyme 1 (Hsd11b1) independently from Prdm16. Even though Hsd11b1 is 1.5-fold upregulated in our Lsd1cKO mice, our cistrome analysis did not provide any evidence for binding of Lsd1 to the Hsd11b1 promoter. Even though the phenotypes of our Lsd1cKO mice and the mice engineered by Zeng et al. (2016) are close, the differences observed in the follow-up cistrome and transcriptome analyses and the interpretation of the molecular mechanism could be explained by the fact that they did not use a brown fat-specific Cre deleter strain.

Recently, Sambeat et al. (2016) proposed that Zfp516 associates with Lsd1 to promote Ucp1 promoter occupancy and gene expression. In clear contrast, our mass spectrometry analysis does not confirm interaction of endogenously expressed Lsd1 and Zfp516 in brown adipocytes. In addition, our ChIP-seq showed that the Ucp1 promoter is not occupied by Lsd1 in brown adipocytes.

Our findings indicate that the use of Lsd1 inhibitors would lead to a shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism in BAT, resulting in weight gain but improved glucose tolerance. These findings need to be considered because Lsd1 inhibitors entered clinical trials, for example in the treatment of mixed-lineage leukemia (Feng et al., 2016). In conclusion, our data identify Lsd1 as a key epigenetic regulator of BAT metabolism.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse Studies

All mice were housed in the pathogen-free barrier facility of the University Medical Center Freiburg in accordance with institutional guidelines approved by the regional board. Mice were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal facility with a 12-hr light/dark cycle, free access to water, and a standard rodent chow (Kliba, breeding, 3807). Male mice were analyzed at 10 or 30 weeks of age. Animals were killed by cervical dislocation, and tissues were immediately collected, weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, or processed for further analyses. In vivo experiments, including food consumption, serum analysis, glucose tolerance tests, temperature measurements, and energy expenditure, were described previously (Duteil et al., 2014). The Lsd1 inhibitor QC6688 was administrated per os at 5 mg/kg in 0.5% methylcellulose (Sigma; product M0512-110G; viscosity, 4,000 centipoise [cP]).

Cellular Metabolism

Cellular metabolic rates were measured using an XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Immediately before the measurement, cells were washed with unbuffered DMEM as described previously (Wu et al., 2007). Plates were placed into the XF24 instrument for measurement of OCR and ECAR with the XFp glycolysis stress kit (103017-100, Seahorse) for ECAR measurements (glucose, 10 mM; oligomycin, 1 μM; and 2 deoxiglucose (2-DG), 50 mM) or the Cell Mito stress kit (103010-100, Seahorse) for OCR measurements (oligomycin, 1 μM; carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), 0.5 μM; and rotenone/antimycin A, 0.25 μM).

Lipid Quantification

Total lipids were extracted from 50 mg of BAT using a lipid extraction kit (STA-612, Cell Biolabs) and quantified using a lipid quantification kit (STA-613, Cell Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Quantification of Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA

BAT was digested overnight with Proteinase K, and DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform. Mitochondria and nuclear DNA were amplified by qPCR using Cox2 and Fasn primers (Table S4), respectively.

Metabolomic and Lipidomic Analyses

Tissue samples were grinded with a Retsch MM440 instrument and further extracted as described in Giavalisco et al. (2009). LC-MS measurements were performed using a Waters ACQUITY ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system coupled to a Thermo Fisher Scientific QExactive mass spectrometer. Details of the analysis are presented in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Data Analysis

Data are represented as mean + SEM. Significance was calculated by

-

(1)

two-tailed Student’s t test for Figures 1G and 1H, 2C and 2D, 4D and 4E, 5C–5G, and 6C–6I and Figures S1A, S1D, S2A, S2C, S2D, S4B, S4C, S4E–S4I, S5A, S5B, S6B–S6E, S6J, S6L, S6N, and S6Q;

-

(2)

one-way ANOVA for Figures 3A and 3C–3E and 4F and Figures S3A, S3E, S3K, and S5D;

-

(3)

two-way ANOVA for Figures 3B and 3F, 4G, and 6A, 6B, and 6J and Figures S3B, S3L, S4K, S4L, S5E, S5F, S6A, and S6P;

-

(4)

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for Figures 5A and 5B and Figures S6H and S6I; and

-

(5)

analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for Figures S6K, S6M, and S6O.

Heatmaps were generated by centering and normalizing expression values with Cluster 3.0 and importing them to MeV viewer.

Author Contributions

R.S. generated the original hypothesis. D.D., M.T., J.M.M., S.U., F.L., T.K., and H.Z.N. performed the experiments. L.A. and T.M. performed the ChIP-seq analysis. D.W. and D.D. performed the bioinformatics analyses. K.P. and J.D. performed the mass spectrometry analysis. N.M. performed the electron microscopy analysis. V.Z. and M.M. performed the lipidomic and metabolomics analyses. J.W.K. and J.C.B. provided the Ucp1-Cre mice. D.D. and R.S. took primary responsibility for writing the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are obliged to F. Pfefferle and L. Walz for providing excellent technical assistance and T. Günther, H. Greschik, and M.J. Castex Armendariz for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the European Research Council (ERC AdGrant 322844 to R.S.) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 992, 850, 746, and Schu688/12-1 to R.S.).

Published: October 18, 2016

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and five tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.053.

Accession Numbers

The accession numbers for the RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data reported in this paper are GEO: GSE81557 and GEO: GSE81557, respectively. The accession number for the mass spectrometry proteomics data reported in this paper is ProteomeXchange Consortium/PRIDE (Vizcaíno et al., 2016) partner repository: PXD004745.

Supplemental Information

The calculation of log2-value is described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

References

- Betz M.J., Enerbäck S. Human Brown Adipose Tissue: What We Have Learned So Far. Diabetes. 2015;64:2352–2360. doi: 10.2337/db15-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birsoy K., Wang T., Chen W.W., Freinkman E., Abu-Remaileh M., Sabatini D.M. An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell. 2015;162:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C., He H.H., Gao S., Chen S., Yu Z., Gao Y., Chen S., Chen M.W., Zhang J., Ahmed M. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 has dual functions as a major regulator of androgen receptor transcriptional activity. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1618–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B., Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P., Spiegelman B.M. Brown and Beige Fat: Molecular Parts of a Thermogenic Machine. Diabetes. 2015;64:2346–2351. doi: 10.2337/db15-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duteil D., Metzger E., Willmann D., Karagianni P., Friedrichs N., Greschik H., Günther T., Buettner R., Talianidis I., Metzger D., Schüle R. LSD1 promotes oxidative metabolism of white adipose tissue. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4093. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J.M., Li L.O., Wu P.C., Koves T.R., Ilkayeva O., Stevens R.D., Watkins S.M., Muoio D.M., Coleman R.A. Adipose acyl-CoA synthetase-1 directs fatty acids toward beta-oxidation and is required for cold thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Yao Y., Zhou C., Chen F., Wu F., Wei L., Liu W., Dong S., Redell M., Mo Q., Song Y. Pharmacological inhibition of LSD1 for the treatment of MLL-rearranged leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016;9:24. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons T.P., Kogan S., Aouadi M., Hendricks G.M., Straubhaar J., Czech M.P. Similarity of mouse perivascular and brown adipose tissues and their resistance to diet-induced inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;301:H1425–H1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00376.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavalisco P., Köhl K., Hummel J., Seiwert B., Willmitzer L. 13C isotope-labeled metabolomes allowing for improved compound annotation and relative quantification in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomic research. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6546–6551. doi: 10.1021/ac900979e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt M., Martin I., Iglesias R., Viñas O., Villarroya F., Mampel T. Ontogeny and perinatal modulation of gene expression in rat brown adipose tissue. Unaltered iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase activity is necessary for the response to environmental temperature at birth. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;193:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms M.J., Ishibashi J., Wang W., Lim H.W., Goyama S., Sato T., Kurokawa M., Won K.J., Seale P. Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab. 2014;19:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner S., Mepani R.J., Laznik D., Ye L., Jurczak M.J., Jornayvaz F.R., Estall J.L., Chatterjee Bhowmick D., Shulman G.I., Spiegelman B.M. Development of insulin resistance in mice lacking PGC-1α in adipose tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:9635–9640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207287109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langin D. Recruitment of brown fat and conversion of white into brown adipocytes: strategies to fight the metabolic complications of obesity? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1801:372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.G., Wynder C., Cooch N., Shiekhattar R. An essential role for CoREST in nucleosomal histone 3 lysine 4 demethylation. Nature. 2005;437:432–435. doi: 10.1038/nature04021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.H., Jung Y.S., Choi D. Recent advance in brown adipose physiology and its therapeutic potential. Exp. Mol. Med. 2014;46:e78. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.H., Mottillo E.P., Granneman J.G. Adipose tissue plasticity from WAT to BAT and in between. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Choi J., Aja S., Scafidi S., Wolfgang M.J. Loss of Adipose Fatty Acid Oxidation Does Not Potentiate Obesity at Thermoneutrality. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Rossmeisl M., McClaine J., Riachi M., Harper M.E., Kozak L.P. Paradoxical resistance to diet-induced obesity in UCP1-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:399–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI15737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger E., Wissmann M., Yin N., Müller J.M., Schneider R., Peters A.H., Günther T., Buettner R., Schüle R. LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature. 2005;437:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature04020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger E., Willmann D., McMillan J., Forne I., Metzger P., Gerhardt S., Petroll K., von Maessenhausen A., Urban S., Schott A.K. Assembly of methylated KDM1A and CHD1 drives androgen receptor-dependent transcription and translocation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:132–139. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musri M.M., Carmona M.C., Hanzu F.A., Kaliman P., Gomis R., Párrizas M. Histone demethylase LSD1 regulates adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:30034–30041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce V., Vidal-Puig A. Regulation of glucose homoeostasis by brown adipose tissue. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1:353–360. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P., Wu Z., Park C.W., Graves R., Wright M., Spiegelman B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambeat A., Gulyaeva O., Dempersmier J., Tharp K.M., Stahl A., Paul S.M., Sul H.S. LSD1 Interacts with Zfp516 to Promote UCP1 Transcription and Brown Fat Program. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2536–2549. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoiswohl G., Stefanovic-Racic M., Menke M.N., Wills R.C., Surlow B.A., Basantani M.K., Sitnick M.T., Cai L., Yazbeck C.F., Stolz D.B. Impact of Reduced ATGL-Mediated Adipocyte Lipolysis on Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3610–3624. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Lan F., Matson C., Mulligan P., Whetstine J.R., Cole P.A., Casero R.A., Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiraby C., Langin D. Conversion from white to brown adipocytes: a strategy for the control of fat mass? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;14:439–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpin S.M., Nicholls H.T., Willmes D.M., Mourier A., Brodesser S., Wunderlich C.M., Mauer J., Xu E., Hammerschmidt P., Brönneke H.S. Obesity-induced CerS6-dependent C16:0 ceramide production promotes weight gain and glucose intolerance. Cell Metab. 2014;20:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C., Mourier A., Bezy O., Macotela Y., Boucher J., Rardin M.J., An D., Lee K.Y., Ilkayeva O.R., Zingaretti C.M. Adipose-specific deletion of TFAM increases mitochondrial oxidation and protects mice against obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;16:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno J.A., Csordas A., del-Toro N., Dianes J.A., Griss J., Lavidas I., Mayer G., Perez-Riverol Y., Reisinger F., Ternent T. 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D447–D456. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Neilson A., Swift A.L., Moran R., Tamagnine J., Parslow D., Armistead S., Lemire K., Orrell J., Teich J. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C125–C136. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Boström P., Sparks L.M., Ye L., Choi J.H., Giang A.H., Khandekar M., Virtanen K.A., Nuutila P., Schaart G. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P., Wang Y., Chen J., Li H., Kang L., Zhang Y., Chen S., Zhu B., Gao S. RCOR2 is a subunit of the LSD1 complex that regulates ESC property and substitutes for SOX2 in reprogramming somatic cells to pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2011;29:791–801. doi: 10.1002/stem.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Jedrychowski M.P., Chen Y., Serag S., Lavery G.G., Gygi S.P., Spiegelman B.M. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 promotes brown adipose tissue thermogenesis via repressing glucocorticoid activation. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1822–1836. doi: 10.1101/gad.285312.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Wang S.Y., Fleuriel C., Leprince D., Rocheleau J.V., Piston D.W., Goodman R.H. Metabolic regulation of SIRT1 transcription via a HIC1:CtBP corepressor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:829–833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610590104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhu D., Hölz S., Metzger E., Pavlovic M., Jandausch A., Jilg C., Galgoczy P., Herz C., Moser M., Metzger D. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 regulates differentiation onset and migration of trophoblast stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3174. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The calculation of log2-value is described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.