Significance

Political beliefs have been shown to spill over into nonpolitical domains, such as consumer spending, choice of romantic partner, and job hiring. Our evidence suggests that political beliefs predict the professional decisions of primary care physicians. On politicized health issues, like marijuana and abortion, physicians' partisan identity is highly correlated with their treatment decisions. Because physicians regularly interact with patients on politically sensitive health issues and because the medical profession is increasingly politicized (e.g., state governments are regulating politicized aspects of medicine), it is necessary to understand how doctors’ own political worldviews may impact their actions in the medical examination room.

Keywords: primary care, physicians, partisanship, politics, health care

Abstract

Physicians frequently interact with patients about politically salient health issues, such as drug use, firearm safety, and sexual behavior. We investigate whether physicians’ own political views affect their treatment decisions on these issues. We linked the records of over 20,000 primary care physicians in 29 US states to a voter registration database, obtaining the physicians’ political party affiliations. We then surveyed a sample of Democratic and Republican primary care physicians. Respondents evaluated nine patient vignettes, three of which addressed especially politicized health issues (marijuana, abortion, and firearm storage). Physicians rated the seriousness of the issue presented in each vignette and their likelihood of engaging in specific management options. On the politicized health issues—and only on such issues—Democratic and Republican physicians differed substantially in their expressed concern and their recommended treatment plan. We control for physician demographics (like age, gender, and religiosity), patient population, and geography. Physician partisan bias can lead to unwarranted variation in patient care. Awareness of how a physician’s political attitudes might affect patient care is important to physicians and patients alike.

In 2015, the US Federal Court of Appeals upheld a Florida state law that forbids physicians from discussing firearms with patients unless doing so is directly relevant to patient care (1). Firearms are hardly the only politicized issue in clinical medicine. When primary care physicians (PCPs) conduct patient interviews, they often engage patients in conversations that touch upon a range of politically sensitive issues, including sexuality, reproduction, and drugs. Because these issues bear directly on health and well-being, they are inextricably tied to a physician's routine work.

Two important bodies of research, one from medicine and the other from the social sciences, raise the possibility that physicians’ political views may influence their clinical practice. Research on clinical practice has revealed substantial variation in patient care by region and at the level of the individual provider (2). Physicians of different genders, for example, have been found to provide different care (3). Physicians have also been found to provide different care to patients based on the patients’ demographic characteristics, like race and ethnicity (4). Just as with other biases, a political or ideological bias might influence medical treatment, particularly on politically salient issues.

From the social sciences, there is recent and growing evidence that, for citizens who identify strongly as partisans, political beliefs can spill over into nonpolitical domains. For instance, whether one's favored party wins an election significantly affects one's happiness (5) as well as one's consumer spending habits (6). Political ideology affects one's evaluation of potential romantic partners (7) and job candidates (8).

Patient advocates and professional organizations seem to acknowledge that doctors with different ideological orientations will provide different care. For instance, the Human Rights Campaign, the largest gay rights organization in America, recommends patients seek referrals for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)-friendly doctors or consult an online directory where such providers are listed (9). The American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists provides an online tool enabling patients to find prolife providers (10).

Scholarly research has also demonstrated a high level of politicization in the medical profession, with sharp differences between Democratic and Republican physicians in their evaluation of the Affordable Care Act (11) and a 350% increase in physicians contributing political donations since the early 1990s (12, 13).

Altogether, the existing evidence leads us to investigate how physicians of different political worldviews engage with patients on politically sensitive issues. We focused on PCPs, who often take a patient's social history in the context of a new patient interview. Based on information gleaned from a history, practitioners may provide verbal counsel as well as particular treatment options when they learn about health risk behaviors. Counseling patients about a range of behaviors, including tobacco use, firearm storage, and obesity, results in real changes in patient behavior (14–16). We used clinical vignettes to evaluate physicians' clinical management, a technique validated by prior research (17).

We hypothesized that Republican and Democratic physicians' evaluations of the seriousness of the issue presented in the vignettes and the choices of treatment options will differ in ways consistent with political bias. We expected to see differences in evaluation and treatment on politicized issues but not on issues with less political salience.

A detailed accounting of our methodology can be found below and in Supporting Information. Our methodology consists of two main components: (i) identifying the voter registration records of PCPs, and (ii) conducting a survey of a stratified random sample of these physicians.

There are several reasons why we linked physician records to voter registration records before conducting a survey. First, we were particularly sensitive to the idea that physicians' survey responses might be influenced by the population of patients they regularly see. Physicians with different ideological worldviews might sort into different practices and thus encounter different patient populations. To control for these possibilities, we not only asked the physicians about their patient population, but we also oversampled Democratic and Republican doctors who were in practice with one another (and were thus assumed to see a similar patient population). To oversample this group, we needed to determine their political affiliation ahead of the survey.

Second, linking the records enabled us to focus the study on Democrats and Republicans. We opted not to study political independents for the sake of efficiency: if there are partisan differences in clinical practice, we expected that they would be most apparent in the comparison between Democrats and Republicans. Third, linking the records enabled us to contact physicians at their home addresses as listed on voter registration files, rather than their work addresses where gatekeepers (e.g., administrative staff) may filter inessential mail that comes their way.

Finally, by using the public record of party affiliation, we did not need to ask physicians about their political affiliation. We purposefully designed the survey to not appear as a political study. For instance, all communications originated from the School of Medicine, not the Department of Political Science. Although at the end of the survey, in a series of demographic questions, we did ask physicians about their ideology, we did not also need to ask directly about partisanship. (We did not end up using the ideology measure in our analysis below because ideology and party are so closely connected in contemporary politics. Of all the Republican respondents to our survey, only three identified as liberal or very liberal. Of all the Democratic ones, only four identified as conservative or very conservative.)

Results

Perceptions of Seriousness.

The central feature of the survey was a series of nine clinical vignettes. The vignettes covered a range of scenarios, some of which were not thought to be especially aligned with political partisanship (alcohol use, tobacco use, helmets, obesity, and depression), others of which were suspected to be more politically salient (marijuana use, elective abortion, firearm storage, and engagement with sex workers). The marijuana, abortion, and firearm vignettes were suspected of being particularly political because there is a sharp partisan divide on these issues in the United States. The nine vignettes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient vignettes

| Issue | A healthy-appearing, 38-y-old male [28-y-old female] patient comes to your office for a physical. This is his [her] first appointment with you. He [She] does not have any known prior chronic medical issues. During the patient interview, the patient... | How serious of a problem, on a 1–10 scale? |

| Alcohol | ...acknowledges consuming about 20 alcoholic beverages in a typical week but denies any related physical concerns. | 7.8 (1.6) |

| Marijuana | ...acknowledges using recreational marijuana approximately three times per week but denies any related physical concerns. | 5.7 (2.3) |

| Tobacco | ...acknowledges engaging in social smoking, consuming ∼15–20 cigarettes per week (2–3 per day), a habit that began at age 18. The patient denies any related physical concerns. | 8.2 (1.7) |

| Sex worker | ...acknowledges having had sexual intercourse with sex workers several times in the last year. The patient denies any physical symptoms related to sexual behavior. | 8.4 (1.8) |

| Depression | ...acknowledges having intermittent bouts of depression. He completed a PHQ-9 screening tool in your office and scored a 10. He denies suicidal thoughts. | 8.2 (1.5) |

| Firearms | ..., who is a parent with two small children at home, acknowledges having several firearms at home. | 7.4 (2.5) |

| Obesity | ..., who has a BMI of 31, acknowledges having no regular exercise. The patient denies any physical complaints related to his weight. | 7.8 (1.5) |

| Abortion* | ...acknowledges having had two elective abortions in the last 5 y. She denies any physical complaints or complications associated with these procedures. She is not currently pregnant. | 5.7 (2.5) |

| Helmets | ...acknowledges commuting to work by motorcycle. He acknowledges rarely wearing a helmet but that he is a safe driver and has never been in a serious collision. | 8.4 (1.9) |

Italics identify more politicized issues. The rightmost column shows unweighted overall means and SDs on a 10-point scale on which respondents indicated the seriousness of the problem presented in the vignette. Number of observations range from 231 to 233 per item. BMI, body mass index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9.

Indicates a vignette with a female patient rather than a male patient.

Following the presentation of each vignette, our survey asked physicians to rate the seriousness of the problem presented by the vignette, on a 10-point scale. Table 1 shows the mean and SD of this 10-point response. The survey offered several management options based on the particular details of each vignette, and asked how likely the physicians would be to engage in each option, also on a 10-point scale. The survey instrument, which is available for review, also asked several other questions related to medical practice, physician attitudes, and demographics.

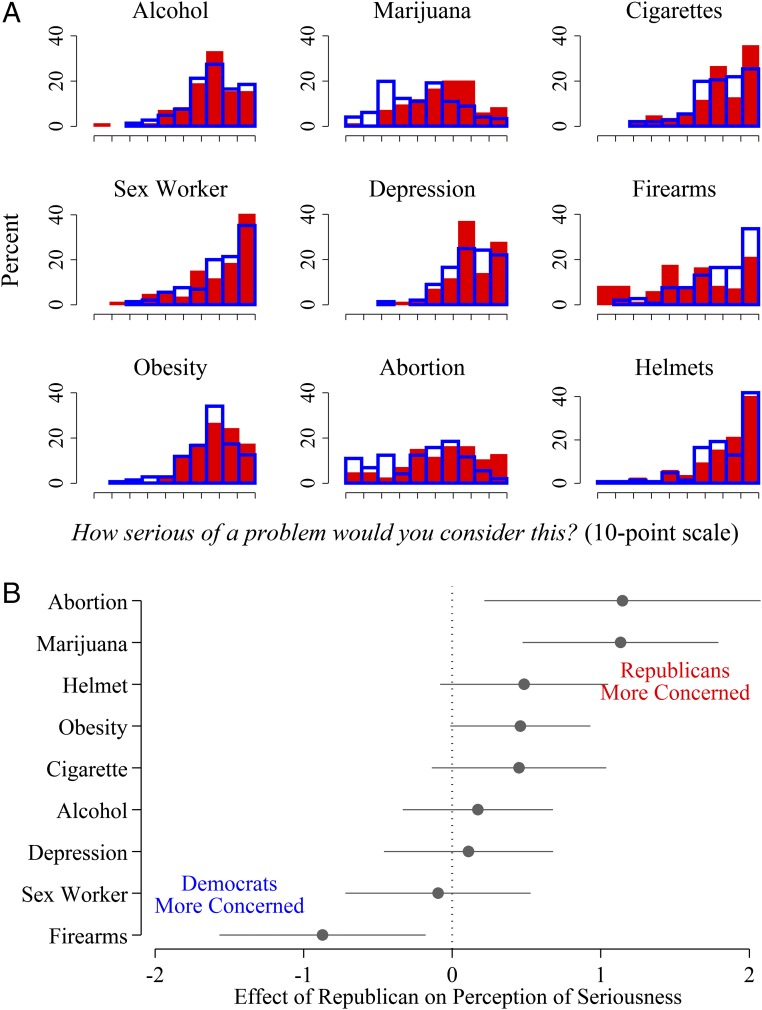

Fig. 1 shows two detailed views of physicians' ratings of seriousness. Fig. 1A illustrates the responses of Democratic versus Republican physicians. On some vignettes, like those relating to alcohol, obesity, and helmets, Republican and Democratic physicians rated the seriousness similarly. However, Democratic physicians rated vignettes related to marijuana, firearms, and abortion substantially differently than Republican physicians.

Fig. 1.

Perceptions of seriousness, by party affiliation. (A) Histograms for each vignette by party affiliation. Red represents Republicans; blue represents Democrats. (B) Circles represent coefficients from regressions, with 95% CIs.

Fig. 1B shows the average difference in seriousness rating between Democratic and Republican physicians based on the regression analysis. Democratic physicians rated the firearms vignette as more concerning, and Republican physicians rated the marijuana and abortion vignettes as more concerning. These differences are based on a 10-point scale, and the SD of these items is 2.2–2.5. Accordingly, these effect sizes are quite large, and they only appear on the politically salient vignettes.

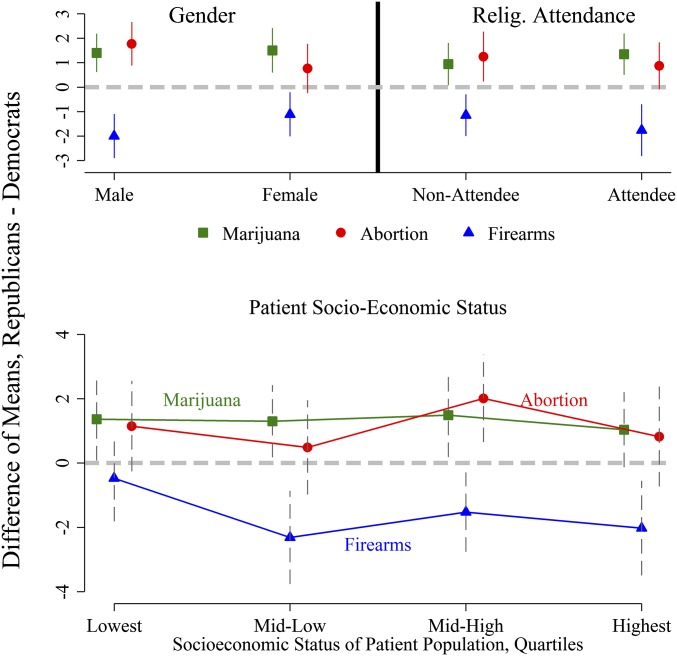

These effects do not appear to be the result of confounding by demographic factors or physician sorting. For the three vignettes that exhibited the strongest partisan differences—marijuana, abortion, and firearms—the partisan differences remain even when respondents are stratified by sex, church attendance, and patient socioeconomic status (SES) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Perceptions of seriousness, by subgroup. Difference of means with 95% confidence intervals are shown. The lower plot uses quartiles of a principal-components factor analysis based on a physicians' perceptions of their patient population.

On the marijuana and firearms vignettes, Republicans and Democrats exhibit similar differences across gender and religious categories. On the abortion vignette, the partisan effect is stronger among men (1.8-point difference for men compared with a 0.8-point difference for women) and similar among religious attendees and nonattendees. Even though Republican physicians are more likely to be male and religious than Democratic physicians, and even though male and religious physicians might treat patients differently than female and nonreligious physicians, Fig. 2 and the regression coefficients in Fig. 1 demonstrate that the partisan effect is independent of these cohort differences.

As with physician demographics, we show that patient population does not appear to explain the partisan differences that we observe. The lower part of Fig. 2 illustrates that doctors who see the lowest SES populations do not exhibit partisan differences on the firearms item, but otherwise there are no notable trends by patient population. In Supporting Information, we address two other ways to account for physician sorting and patient population. First, we compare physicians in mixed-partisan practices versus physicians in the general sample. Second, we estimate a model that employs practice-level fixed effects, analyzing just those practices for which we have multiple respondents.

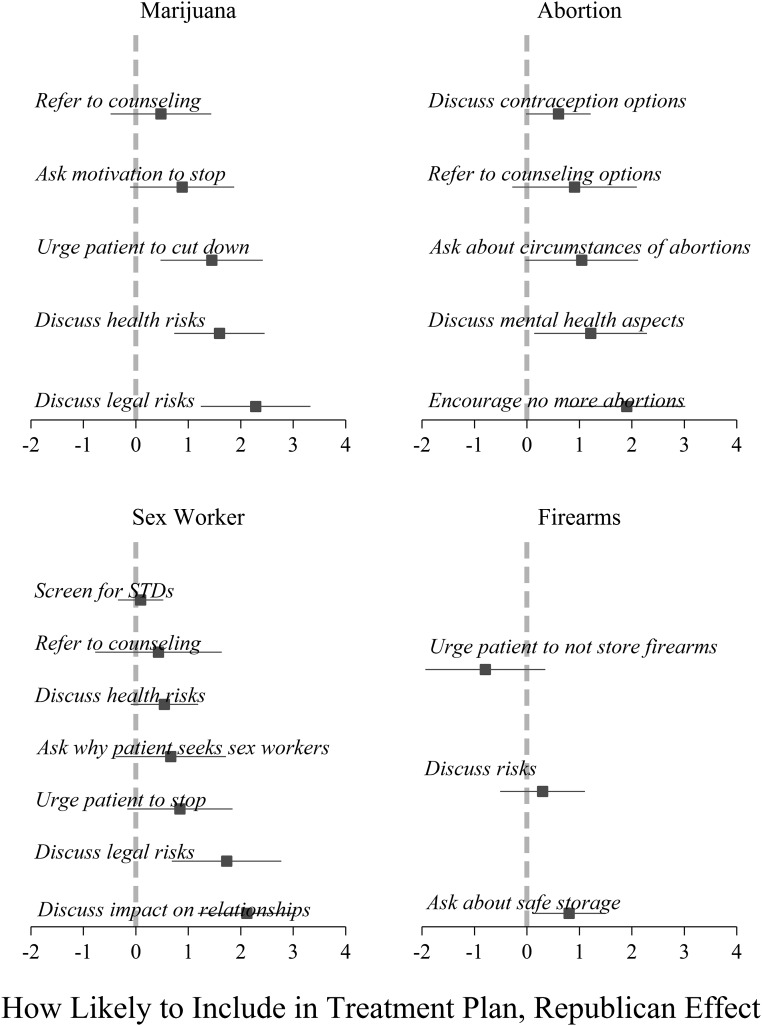

Management/Treatment Plans.

Fig. 3 shows the various treatment options offered in the survey for the four more politicized issues. Republicans are more likely to discuss health risks of marijuana, urge the patient to cut down, and discuss legal risks. Republicans are more likely to discuss the mental health aspects of abortion and to encourage the patient not to have more abortions. Although Democratic and Republican physicians did not differ on the judgment of seriousness of using sex workers (a vignette that reflects a moral issue but not one that corresponds to a sharp partisan division), Republican physicians are more likely to discuss legal risks and discuss the impact on personal relationships. Democratic physicians may be more likely to urge patients not to store firearms at home, but Republican physicians are significantly more likely to ask about the safe storage of the weapons.

Fig. 3.

Partisan differences in treatment plans on politicized issues. Points represent coefficients from regression, with 95% CIs. Positive values indicate that Republicans are more likely to include a particular item in a treatment plan; negative values indicate that Democrats are more likely to do so.

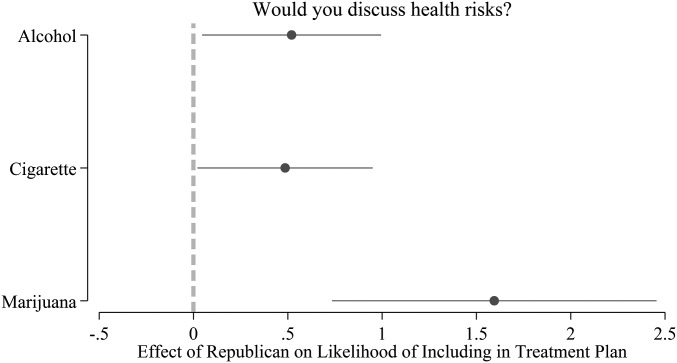

Republicans, in general, were more likely to say that they would engage in active treatment options than Democrats. However, the degree of difference varies by the politicization of the issue. As Fig. 4 shows, on the less politicized issues of alcohol and cigarettes, Republican physicians appear only slightly more likely to discuss health risks than Democratic physicians. On the marijuana vignette, the difference is over three times larger.

Fig. 4.

Partisan differences are especially pronounced on politicized issues. Note: Points represent coefficients from regression, with 95% CIs.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that Republican and Democratic physicians differently assess the seriousness of patient health issues that are politically salient. Republican physicians also differ from Democratic physicians in the treatments offered to patients who present with those health issues. The direction of the differences is consistent with expected political leanings (Democratic physicians are more concerned about guns in the home; Republicans are more concerned about patient drug use and a patient having had abortions). The data analysis suggests these differences cannot be otherwise explained by demographic traits of physicians or by the patient populations they encounter.

Of course, party identification may be a surrogate measure of some other, unmeasured characteristic (e.g., a personality trait, ideology, socialization) that is correlated both with political allegiance and with treatment approach. Evidence like that presented in Fig. 4 leads us to believe that whatever is driving our results is closely related to politics. The figure shows that Republican physicians are not just generally more assertive in treatment than Democrats (which might be attributable to a personality difference), but that they are particularly more assertive on the marijuana vignette, an issue with political salience but with a lower associated health risk (18).

To be clear, we cannot say with any certainty what the root cause of partisan differences in treatment is. However, regardless of the underlying mechanism that affects physician judgment, the evidence suggests a clear effect from the patient's perspective. If we assume that a patient selects a physician based on the physician's practice location, gender, age, and so forth (i.e., control variables in our models), but not on other factors correlated with political party, which is a reasonable assumption, then we expect patients to get different medical care depending on whether they happen to have selected a Republican or Democratic physician.

This study demonstrates the connection between provider political orientation and medical care. Our initial findings should compel further research seeking to replicate and extend our work. Our survey achieved a reasonable response rate given the lack of financial incentives offered to respondents, and although a substantial body of work suggests that response rates in this range do not generate biased responses (19), this topic merits financial support and attention to extend the work.

Future research could include examinations of partisan differences in actual clinical care, not just in survey responses. Researchers could accomplish this either by using public records of reimbursements or by linking party affiliation data to internal records of partnering provider networks. Although our initial study focused on politicized issues related to abortion, marijuana, and firearms, future studies that use clinical records might examine other politically sensitive topics, such as end-of-life care in Medicare patients and treatments related to LGBT health.

Our study faces a familiar set of limitations that should be acknowledged. We only solicited 1,529 physicians in 29 states and, without offering respondents incentives, achieved a response rate of 20%. As we report in Supporting Information, comparisons between the sample and population on observable variables are encouraging, but the respondents are not perfectly representative. Specifically, Democrats were more likely to respond to our solicitation than Republicans. As another matter, our method of linking physicians to voter registration records provided us with important tools in pursuing the research question. However, we were not able to match all physicians to public records, and this too may result in unknown biases. Finally, although survey vignettes have been validated as strong indicators of actual clinical practice, our study is limited by the potential for misreporting bias to affect the results. By not alerting physicians to the political nature of the study, we hope to have avoided one important set of concerns about misreporting bias, but the problem remains that responses may not perfectly convey the true professional judgments of the respondents.

Conclusion

Having acknowledged these limitations, our study suggests the following conclusions. For patients, our study suggests that they may need to be aware of their physician's political worldview, especially if they need medical counsel on politically sensitive issues. As mentioned, advocacy groups like the Human Rights Campaign already attend to this regarding LGBT patients, and our evidence suggests that such sensitivity is warranted. Just as a patient may seek out a physician of a certain gender to feel more comfortable, the evidence suggests that a patient may need to make the same calculation regarding political ideology.

For physicians, the evidence calls for heightened awareness and training surrounding treatment on politically salient issues. Given the politicization of certain health issues, it is imperative that physicians consider how their own political views may impact their professional judgments.

Methods

Survey Sample.

We downloaded the National Provider Identification (NPI) file of US physicians and identified physicians in the primary care specialties of internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, and adult medicine. (The NPI file is a comprehensive listing of physicians who are covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Some physicians who do not use electronic systems and do not accept insurance may not have an NPI number.) We restricted our attention to physicians practicing in the 29 US states in which registered voters are listed in the public record according to their party affiliation. Previous research has shown that these states are representative of the nation as a whole (20, 21). We drew a 50% simple random sample of PCPs in these states (42,861 physicians) who were listed with their name, gender, and work address.

We transmitted the identifying information from the NPI record to Catalist, a political data firm that aggregates voter registration records and vends these data to political organizations, researchers, and government agencies (22, 23). Based on the name, gender, and work address, we were able to match 57% of the physicians to a unique record on the public voter file. (Physicians would not match to a unique record either because they are not registered voters or because their name and location linked to multiple plausible matches on the voter file.) [Overall, in the United States, approximately 71% of citizens are registered (24). Among physicians who are citizens, we would expect a higher rate of registration because registration is positively correlated with SES, but, of course, many of the practicing physicians listed in the NPI file are not American citizens.] All comparisons were among physicians who were matched. On covariates available in the NPI file (e.g., gender, specialty, physicians per practice address), the matched records appeared nearly identical to the records originally transmitted to Catalist (Figs. S1–S3 and Table S1). Among physicians who matched to voter registration records, 35.9% were Democrats, 31.5% were Republicans, and the remaining 32.6% were independents or third-party registrants. Among the partisans, 53% were Democrats, and 47% were Republican. Because of this nearly even split, we did not stratify the sample based on individual physician partisanship.

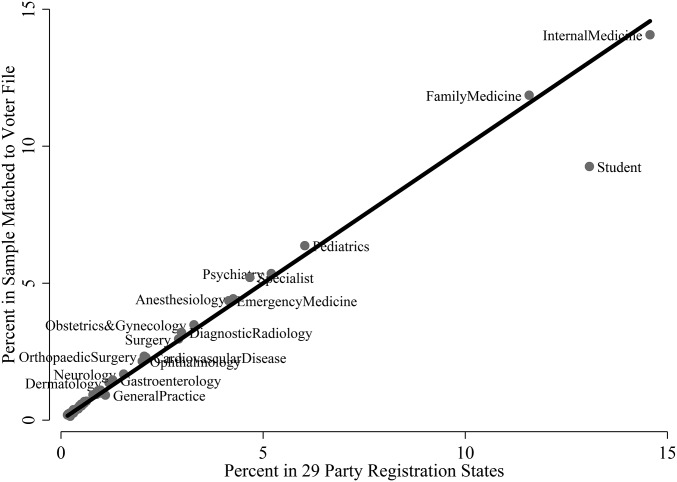

Fig. S1.

Specialty of physicians in NPI file vs. physicians in NPI-Catalist–matched sample.

Fig. S3.

Distribution of NPI physicians vs. NPI-Catalist–matched physicians on zip code population.

Table S1.

Observable traits of physicians on NPI file

| Statistics | All states (1) | Party registration states (2) | 50% Sample (3) | Catalist matched (4) |

| Percent female | 36.8 | 37.1 | 37.3 | 36.9 |

| Specialty | ||||

| Percent internal medicine | 51.2 | 53.3 | 52.9 | 51.5 |

| Percent family medicine | 44.0 | 41.7 | 42.1 | 44.0 |

| Percent adult medicine | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Percent general practice | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| No. physicians at address | ||||

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| N | 149,936 | 85,722 | 42,861 | 20,296 |

The number of physicians at the practice address is constructed based on the address information on the NPI file. For example, all physicians whose practice address is 15 Main Street, Suite 500, in a particular city and state would be grouped in a single practice.

Altogether, we solicited 1,529 physicians.

Survey Administration.

In September 2015, we sent an introductory postcard to the physicians, alerting them to a larger packet of materials forthcoming in the mail. Two weeks later, we mailed a packet that included a consent document, survey instructions, a paper version of the survey, and a prepaid return envelope. All correspondence went by mail to physicians' home addresses, which we obtained from the voter file. Respondents were invited to take the survey online or on paper. In December 2015, we resolicited individuals from whom we had not yet heard. We offered no incentives for participation, financial or otherwise.

Our study was approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Committee, Protocol 1506016032. Respondents were shown an “informed consent” script as part of the survey materials, which explained that participation in the study was voluntary and that completion of the survey implied consent.

We achieved a response rate of 20%, a rate consistent with contemporary surveys of professional elites (like physicians) that offer no incentives. [For example, a 2009 survey of scientists conducted by Pew generated a response rate of 25% (25).] As detailed in Supporting Information, respondents did not differ significantly from those solicited on characteristics including gender, medical specialty, block-group median household income, or in the proportion in the oversample of mixed-partisan practices. The respondents were slightly older (mean age: 53 vs. 49) and were more Democratic (63% vs. 53%) than the nonrespondents (Tables S2–S5). Although Democrats were more likely to respond than Republicans, the survey instrument (which can be reviewed in the replication materials) offered no obvious indication of this being a politically oriented study.

Table S2.

Construction of oversample

| Percent Republican | ||||

| Practice size | 0–20 | 20–80 | 80+ | Total |

| Small (1–3) | 5,600 | 1,253 | 5,180 | 12,033 |

| Medium (4–10) | 348 | 754 | 151 | 1,253 |

| Large (11+) | 205 | 187 | 0 | 392 |

| Total | 6,153 | 2,194 | 5,331 | 13,678 |

We derived our sample from 13,678 party-registered physicians with mailable residential addresses. We stratified the sample by practice size and practice percent Republican. Practice size here is determined by the number of Democratic and Republican physicians in our sample. For midsized mixed-partisan practices (indicated in bold), we sampled all 754 physicians. We sampled 6% of all other cells to generate an overall sample of 1,529 physicians.

Table S5.

Response bias

| Statistics | Survey sample (6) | Survey respondents (7) | P value |

| Percent Female | 39.2 | 42.9 | 0.14 |

| Specialty | |||

| Percent internal medicine | 54.3 | 56.5 | 0.39 |

| Percent family medicine | 42.2 | 41.5 | 0.78 |

| Percent adult medicine | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.12 |

| Percent general practice | 2.8 | 2.0 | 0.34 |

| No. physicians at address | |||

| Median | 9 | 6 | |

| Age | 49.5 | 53.0 | <0.01 |

| Percent Democratic | 55.3 | 62.5 | <0.01 |

| Block group median income, $ | 78,114 | 79,565 | 0.42 |

| Percent in mixed-partisan practices | 55.4 | 50.2 | 0.04 |

| N | 1,529 | 301 |

Difference of mean P value is the difference between respondents and nonrespondents.

Given the relatively small number of physicians solicited and the response rate, our sample size is not large. For our key dependent variables, our sample size is 231–233 physicians. Despite the sample size, we witness strong and consistent support for our hypotheses. As indicated above, the relationship between partisanship and medical treatment persists even within subgroups of our sample, such as gender and religiosity cohorts, and among Democratic and Republican physicians in practice with one another. Although we approach small samples with caution, such caution here is balanced against the consistency and strength of the evidence.

Statistical Analysis.

In addition to simple histograms and differences of means, we used regression analysis. The dependent variable was either the physician's rating of the seriousness of the issue or the physician's assessment of their likelihood of choosing a specific management plan. The key independent variable was a binary indicator that distinguishes Republicans (1) from Democrats (0). We included controls for physician age, gender, and religious attendance, and an indicator that distinguishes physicians in the oversample of mixed-partisan practices from physicians in the general sample.

We controlled for patient population by using a scale generated from respondents' estimates of the percentage of their patients who are college educated, on Medicaid, generally healthy, black/African American, and non-English speaking. These items were combined using principal-components analysis to generate a single continuous scale indicative of the patient population's SES.

In addition to controlling for patient population of the individual physician, our regression analysis employs state fixed effects, such that average state differences in responses are accounted for. Our model also employs robust SEs clustered at the physician's practice address.

Linking Physicians to Voter Data

A key innovation in this study is the linking of physicians to their voter registration records. There are several reasons why this is an important feature of our study. First, we did not want to alert survey respondents to the political nature of our study. By obtaining public records of physicians' political party affiliation, we did not need to ask questions about political affiliations. The public record of political party affiliation is very highly correlated with one's self-reported partisan identity and with vote choice in elections (20).

Second, and more importantly, by linking to party registration data, we were able to pinpoint the sample and gain efficiency. Because we conjectured that any partisan spillover effects would be most pronounced among partisans, we were able to survey known partisan affiliates. We were also able to oversample partisan physicians in mixed partisan practices. We could not have done this oversampling if we were unaware of the physicians' partisanship before conducting the survey.

Third, linking physician records to voter registration data allowed us to obtain up-to-date residential addresses for physicians. Targeting home addresses is useful for two reasons. First, the work address listed on a physician's National Provider Identification (NPI) is not likely to be updated as frequently as a voter registration file. Moreover, physicians typically have gatekeepers (e.g., administrative staff) at their offices who may filter inessential mail that comes their way. In our study, we bypassed gatekeepers by targeting physicians at their home addresses.

Data and Linkage Technique.

The first step in linking physicians to their voter file records was to obtain a list of physicians. Our database began with the NPI file of US physicians. The NPI file is maintained by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and it is updated monthly. It can be downloaded from download.cms.gov/nppes/NPI_Files.html. We downloaded the NPI file that was updated as of September 7, 2014.

The NPI file is a comprehensive listing of physicians who are covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). When we downloaded the file, it contained records of 560,896 individual physicians. Each physician is listed with a number of characteristics, including name, practice address, gender, medical specialty, and various state license numbers (e.g., Medicaid identification numbers). Although physicians who make electronic HIPAA transactions are expected to update their NPI information regularly, an agent at CMS informed us that not all physicians do this. However, because we did not rely on practice address as a basis for contacting physicians, old addresses were not a major concern.

For the purpose of linking the NPI with other public records, we engaged in a standard set of data-cleansing techniques, such as removing characters like dashes and apostrophes from names.

Next, we restricted our sample in two important ways. First, we concentrated on physicians in primary care specialties. These include the specialties of internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, and adult medicine. Not all physicians with these specialties practice primary care, an issue we deal with at a later stage of analysis. Second, we further restricted our sample to physicians with practice addresses in 29 states in which registered voters can register with a party affiliation. As discussed in previous work, the states that use party registration are representative of the entire nation (18, 19). On the observable traits available on the NPI file, this representativeness is borne out, as illustrated in Table S1.

There were 85,722 physicians with primary care specialties in the 29 party registration states. We drew a simple random sample of 50% of these physicians. In March 2015, we transmitted this sample to a voter file data vendor called Catalist LLC. Catalist maintains a continuously updated national voter file, with detailed information about all registered voters in the United States. Catalist data are generally used by political campaigns engaged in electioneering, but the firm also regularly services academic and governmental requests.

For each physician, we transmitted to Catalist the first, middle, and last name; name suffix; alternate last names (usually maiden names); genders; and work addresses. Catalist performed a one-to-many distance match on our records. Specifically, Catalist used the name, gender, and the geographic centroid of the physician's workplace address, and assigned matching confidence scores to registered voters. For each physician, Catalist searched for plausible matches within a commuting distance of 50 miles from the work address.

Of the 42,861 records we sent, 43% of them had a single unique match in the Catalist file. The remaining physicians had no matches or multiple matches, but from some of the ones with multiple matches, we were able to confidently obtain unique matches. Specifically, if one record on the physician list matched to multiple records on the voter list, but if there was a single record on the voter list with the same middle initial or middle name as the physician list, and if all of the other plausible matches were listed with middle initials or names but they did not match the physician record, then this would result in a match. Similarly, if a John Doe, Jr., matched to two records, a junior and a senior, we treat the match to the junior record as a unique match. Finally, if there was one plausible match on the voter file that was much closer, in terms of geographical distance, to the work address than all of the other matches (i.e., if the second closest residential address on the voter file was more than 15 miles farther from the work address than the closest match), then we considered this a match.

After executing these procedures, we obtained a matched list of 24,250 physician records matched to Catalist voter registration records, 57% of the initial sample. For this particular match between NPI records and voter registration records, our objective was to minimize false positives. That is, we wanted to avoid sending our survey to individuals who were not actually our target physicians. If we wanted to maximize matches rather than minimize false positives, we could have allowed for a more permissive matching process, but we wanted to avoid sending our survey to individuals who are not physicians.

Generating the Survey Sample.

To generate our survey sample, we took the list of 24,250 primary care physicians (PCPs) and deleted those whom Catalist determined were either unmailable or were obsolete records. An obsolete record is one in which Catalist determined the person does not live or vote at that particular household. This brought us to a list of 20,296 records.

Table S1 shows several traits of physicians at four stages of our procedure. Column 1 shows physicians in the four specialties in our study in the US column 2 is restricted just to party registration states. Although we have only a few observable characteristics to compare, there appear no stark differences between these columns. Column 3 is a simple random sample of the second column, and the statistics remain the same. The fourth column represents only those physicians who matched to unique voter file records and had mailable addresses. A comparison between columns 1 and 4 shows that the matched records are almost identical to the full national population of PCPs.

From the 20,296 matched records, we restricted the sample just to registered Democrats and Republicans, ignoring unaffiliated and third-party registrants. This brought our list to 13,678 records. Again, we focused on partisans because we conjectured that, if any differences were to emerge, they would be especially pronounced in the comparison of Republicans to Democrats. Because two-thirds of the physicians in our sample are partisans (i.e., 13,678/20,296), it is clear that we are studying differences among a large subset of PCPs, not an outlier contingent of hyperpoliticized individuals.

We aimed to oversample a particular set of physicians—those in mixed-partisan practices. As we discuss in the article, we did this to accommodate a concern that physicians of different political worldviews may sort into different practices and therefore see different patient populations.

To generate our oversample, we clustered the sample in two ways. First, we counted the number of doctors who matched to the voter file at each practice address, such as a particular suite in an office building. To focus on physicians who are in a small enough practice such that they might share a patient population, we focused on doctors in practices for which we had between 4 and 10 matched, party-affiliated physicians. Next, we focused on the partisan composition of these doctors who shared a practice address. We classify practices as mixed partisan if between 20% and 80% of the doctors are Republican affiliates. Seven hundred and fifty-four physicians who matched to Catalist were party affiliated, and practice in midsize, mixed-partisan practices. We included all of these physicians in our survey sample. To obtain a final survey sample of ∼1,500 physicians, we drew a 6% simple random sample of all of the party-registered matched physicians who were not in the midsize mixed-partisan practices. This resulted in a final sample of 1,529 physicians. Table S2 illustrates the sample construction based on the practice size and practice percent Republican strata.

Table S3 shows observable traits from the NPI database and from the Catalist voter file for three steps in our procedure. The first column is labeled column 4 because it is a repetition of column 4 from Table S1 representing the 20,296 physicians who matched to unique records on the voter file. In this table, we show a number of characteristics obtained from the Catalist voter file, including the average age, percent Democratic (among Democrats and Republicans), and median household income of the physician's Census block group. We also show the percentage of physicians who are in the mixed-partisan practices as defined by the two strata in Table S2.

Table S3.

Observable traits of Catalist matches and survey sample

| Statistics | Catalist matched (4) | Catalist matched, Democrats and Republicans only (5) | Survey sample, unweighted (6) |

| Percent Female | 36.9 | 36.4 | 39.2 |

| Specialty | |||

| Percent internal medicine | 51.5 | 48.6 | 54.3 |

| Percent family medicine | 44.0 | 46.7 | 42.2 |

| Percent adult medicine | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Percent general practice | 3.3 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| Median physicians at address | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Age | 50.9 | 52.0 | 49.5 |

| Percent Democratic | 53.3 | 53.3 | 55.3 |

| Block group median income, $ | 83,052 | 82,152 | 78,114 |

| Percent in mixed-partisan practices | 14.1 | 16.0 | 55.4 |

| N | 20,296 | 13,678 | 1,529 |

The second column of data in Table S3 restricts the analysis only to Democratic and Republican physicians, ignoring independents. Notice that, on the observable traits like gender, age, block group income, and medical specialty, the partisan physicians are quite similar to the full sample of physicians. Finally, the third column shows the final survey sample. This represents the 1,529 physicians whom we solicited. Notice that the percentage in mixed-partisan practices goes from about 15% in the first two columns to 55% in the third column. Purposefully, one-half of our solicitations were sent to doctors in these kinds of practices. Because of the oversample, slight differences emerge on other observable traits; however, even with the oversample, the overall set of solicited physicians looks quite similar to the full population. Of particular interest is the percent Democratic. Among all matched records, 53% of party registrants are Democratic. In our final survey sample, 55% are Democratic. In the population and in our sample, there is approximate balance between Democrats and Republicans, so we did not stratify our sample based on physician partisanship.

Survey Method and Response

We sent three communications to physicians in our sample, all by US mail to physicians' home addresses. In the first week of September 2015, we sent an introductory postcard. This postcard alerted physicians of the packet of materials to come and invited physicians to learn more about the study and fill out the survey online by navigating to a website we established. The website contained all of the materials that were included in the larger mailer. Two weeks later, we then sent the main mailer. All of the materials are available for review on E.D.H.’s website, www.eitanhersh.com. Finally, in December 2015, we recontacted only those physicians from whom we had not yet heard. Our study was approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Committee, Protocol 1506016032.

Of the 1,529 physicians solicited, we received undeliverable mail from 47 individuals. One respondent contacted us to let us know that he refused to participate. We asked individuals who received the mailer in error—because they were not physicians—to let us know of the error. Using the methodology of linking the NPI file to matches on the voter file, only eight individuals contacted us to tell us that they were not the intended recipients of the survey.

We received responses from 301 physicians, which, as Table S4 shows, results in a response rate of 20%. Not every physician whom we solicited regularly engages in primary care. We asked respondents to notify us if they did not perform primary care services. These physicians may work as specialists or as researchers. Accordingly, our survey analysis is focused on the 233 respondents who are engaged in primary care. Focusing on this subset does not result in an alteration of the response rate because the population of solicited physicians is necessarily inflated; not all those solicited are the target of our study because not all those solicited are PCPs.

Table S4.

Response rate

| Row | Classification | N |

| 1 | Solicited | 1,529 |

| 2 | Returned mail | 47 |

| 3 | Refused | 1 |

| 4 | Not physician | 8 |

| 5 | Physician response | 301 |

| 6 | Not PCP | 68 |

| 7 | Complete/near complete | 233 |

| 8 | Response: (5)/(1-2-4) | 0.20 |

Table S5 shows comparable observable traits between the 301 respondents and the 1,529 physicians in our sample. Notice the first column here is labeled column 6 as it is the same subset of data as in the last column of Table S3. As we report in the article, the respondents to our survey are fairly representative of the solicited physicians on most variables available, with one important exception. Democratic physicians were significantly more likely to respond to our survey. Whereas Democratic physicians composed 55.3% of our sample (column 6), they composed 62.5% of our respondents, a 7 percentage point difference.

Although we cannot be certain, we do not suspect the partisan differential in response rate affects our results. We made an effort to make sure respondents were not alerted to the political nature of the study. The mail solicitations came from Yale School of Medicine (not the Yale Department of Political Science), and as can be seen from the survey materials at the end of this document, there are no obvious signs in the study that our focus is political. We did ask physicians about their ideology at the end of the survey, when we also asked them questions about demographics, religious participation, and so forth. We ended up not using this question simply because political party and political ideology are so closely tied (we had almost no Democrats who identified as conservative or Republicans who identified as liberal). We do not think that this question at the end of the survey would have caused Democratic and Republican physicians to respond differently on account of the political focus of the study. Nevertheless, as with any survey that does not have complete participation, there is the potential for response bias to affect results.

Supplementary Tables and Analysis

Figs. 1, 3, and 4 in the article show regression coefficients. The full regression outputs can be recovered through the code and data files provided in the replication folder. For Fig. 1, the dependent variable is the 10-point scale on which respondents rated the seriousness of the health issue presented in the vignette. The key independent variable is an indicator where Republicans have a value of 1 and Democrats have a value of 0.

The control variables are as follows. Age is included in years. Gender is included as an indicator for female. For religious attendance, we used a survey question that asked physicians, “Apart from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services?” Forty-two percent of respondents claimed to attend at least once a month. We distinguish this group from those who said they attend a few times a year or less using an indicator.

As discussed in the paper, we generated a scale that reflects the socioeconomic status (SES) of the physician's patient population. We asked physicians to estimate the percentage of their patients who were college educated, on Medicaid, generally healthy, black/African American, and non-English speaking. (We also asked about the percentage of patients under age 30, over age 60, and white/Caucasian, but we did not include these in building our SES scale.) We used principal-components analysis to combine the five percentages. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 2.2, and no other factor had an eigenvalue above 1. The scale ranges from −3.5 to 2.2, with mean 0 and SD 1. Higher values indicate that the physician estimates the patient population is higher in SES.

The model includes a final indicator that distinguishes physicians in the oversample of mixed-partisan practices from physicians in the general sample. Consult Table S2 and related discussion about the criteria for the oversample. Finally, the models all use state fixed effects and robust SEs clustered at the practice address.

The regression coefficients in Figs. 3 and 4 use exactly the same regression models as those just described, except the dependent variables are the respondents' assessments of how likely they are to include particular items in their treatment plans.

Physician Sorting and Patient Population.

In Fig. 2, we show evidence that physicians' perceptions of seriousness do not vary with the physicians' patient population. In particular, we use the SES scale and show that Democratic and Republican physicians evaluate politicized issues differently from one another, in both high-SES and low-SES patient populations. There are three other ways we can explore differences by patient population.

First, as we discuss above, all of the regression analysis employs state fixed effects, so the partisan differences emerge even when controlling for patient SES within states. Second, as we mention in the paper, the physicians in the oversample of mixed-partisan practices evaluate the vignettes similarly to physicians in the general sample. For the marijuana vignette, the Democrats in the oversample evaluated the issue as 1.7 points less serious than Republicans (n = 101; P < 0.001). In comparison, the Democrats in the regular sample evaluated the issue as 1.1 points less serious (n = 130; P < 0.01). For the firearms vignette, Democrats in the oversample evaluated the issues as 1.6 points more serious (n = 104; P < 0.001). In comparison, the Democrats in the regular sample evaluated the issue as 1.8 points more serious (n = 128; P < 0.001). Finally, in the abortion vignette, the Democrats in the oversample evaluated the issue as 1.1 points less serious than Republicans (n = 104; P = 0.02). In comparison, the Democrats in the regular sample evaluated the issue as 1.4 points less serious (n = 129; P < 0.01). In short, physicians in the mixed-partisan practices responded much the same way as physicians who do not practice with members of the other party.

Another approach to studying how the physician responses vary by patient population is to use practice-level fixed effects. For a small subset of practices—20 in total—we received responses from Democrats and Republicans in the same practice. Fixed effects ignores all respondents except those for whom we have multiple respondents per practice. Obviously, focusing on just 20 practices and fewer than 50 respondents in those practices does not provide us with much statistical power; however, it is worthwhile to use fixed effects to determine whether the partisan effects hold up within practice.

Consider fixed-effects regression models in which the dependent variable is the respondent's perception of the seriousness of the marijuana, abortion, and firearm vignettes. The same set of control variables are used as in the rest of the analysis, but now we use practice-level fixed effects instead of state-level fixed effects. In the marijuana model, the coefficient on Republican is 1.81 (SE = 0.90; P = 0.06). In the abortion model, the coefficient on Republican is 2.44 (SE = 1.36; P = 0.09). In the firearm model, the coefficient on Republican is −1.57 (SE = 1.02; P = 0.14). In all three cases, the coefficient estimate is larger than in models that leverage the full set of data, but because there are only about 50 observations in the 20 practices for which we have multiple responses, the estimates are not significant at the 0.05 level, although in all cases they approach conventional thresholds for statistical significance.

Is it possible that Democratic and Republican physicians within the same practice see different patient populations? Per a reviewer's suggestion, we evaluate this possibility by predicting the SES scale, as generated by respondents' assessments of their patient population, with the indicator distinguishing Democratic and Republican physicians, in a regression that employs practice fixed effects. In this regression, the coefficient on Republican is −0.12 (SE = 0.25; P = 0.62). Thus, partisanship does not predict patient SES among respondents in practice with one another.

The evidence from the model using practice fixed effects, in addition to the evidence regarding patient SES, is strongly suggestive that the partisan effect is not a function of physician sorting into different patient populations.

Political Contextual Factors.

Do survey responses vary by political context? A helpful reviewer of this manuscript suggested a few tests to evaluate this question. First, we explore whether the effect is different in Republican-leaning states than in Democratic-leaning ones. As indicated, all of the analysis in the paper use state fixed effects, so the analysis is accounting for average differences between, say, Iowa and Massachusetts. However, the paper does not explore interactive effects with respect to political context. Of course, given the sample size, we are limited in how much we can subdivide the data.

Suppose we divide the states in our sample into those where President Obama won the popular vote in 2012 and those in which he lost. It happens that we have about three times as many respondents from states that went to the Democrat than went to the Republican. For our key political vignettes (marijuana, abortion, and firearms), we run a regression in which the dependent variable is the 10-point rating and the independent variable is an indicator for Republicans. We cluster SEs around the practice, but we do not here incorporate other controls or fixed effects. This is simply because in the states that President Obama lost, we only have 47–48 respondents and so we lack power for a more complete analysis. Dividing the sample into Democratic-voting states and Republican-voting states, we see similar coefficients on Republican for the marijuana vignette: 1.40 (SE = 0.33; P < 0.001) in Democratic states and 1.16 (SE = 0.56; P = 0.04) in Republican states. We also see similar effects in Democratic and Republican states for the abortion vignette, although the effect is stronger in Republican states. The coefficient in the Democratic states is 0.99 (SE = 0.41; P = 0.02). The coefficient in the Republican states is 2.17 (SE = 0.60; P = 0.001). For the firearms vignette, we see stronger effects in the Democratic states [coefficient is −1.87 (SE = 0.41; P < 0.001)] compared with the Republican states [coefficient is −0.84 (SE = 0.68; P = 0.22)]. However, we should use caution when interpreting these differences as the sample was not drawn to be representative of political context and the sample size is small in the states that President Obama lost.

A separate question of political context is whether the marijuana vignette exhibits a different pattern in the states that have legalized marijuana. Marijuana legalization laws are in flux and fairly nuanced. However, if we focus on the party registration states that have the most liberal marijuana laws (e.g., Colorado, Oregon, Alaska), we observe that the partisan effect is just as strong as in the full sample. Specifically, if the dependent variable is the marijuana rating, the independent variable is the indicator for Republicans, and we use clustered SEs at the practice level, the coefficient on Republican is 1.39 (SE = 0.28; P < 0.001) in the full sample and 1.45 (SE = 0.87; P = 0.12) for 22 respondents in the states where marijuana is legal.

A third question of political context relates to state firearm laws. Here, we wanted to see whether the effects are similar in states with strict firearm laws as those with less strict laws. Specifically, we look at states as categorized by the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence (26). The more restrictive states include California, Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. The less restrictive states include Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, New Mexico, Nevada, and Wyoming. In the full sample, if we treat the firearm vignette rating as the dependent variable and the indicator for Republicans as the independent variable (using SEs clustered at the practice), the coefficient on Republican is −1.72 (SE = 0.35; P < 0.001). In the most restrictive states, the coefficient is similar at −1.76 (SE = 0.62; P = 0.006). In the least restrictive states, the effect is smaller at −0.67 (SE = 0.70; P = 0.34).

In sum, we see the most consistent effects across political context with regard to the marijuana vignette. The abortion and firearm vignette are consistent in the direction of the effect but not in the magnitude of the effect size across contexts. This variation may be the result of a small sample and limited power to evaluate subpopulations or it may be a real difference across contexts. This suggests an opportunity for future work to design studies appropriate for evaluating political effects as they vary by political context.

More Details on Link Between NPI File and Catalist.

The sample of PCPs was just one of four samples that we matched to Catalist records. We also matched a general sample of all physicians (across all specialties) in party registration states. We also oversampled physicians in two states (North Carolina and Massachusetts) for future research. In total, we sent 92,831 records to Catalist and obtained unique matches for 57.8% of these records. Slightly more male providers (58.6%; n = 60,944) matched than female providers (55.8%; n = 31,887). Although the bias is not very large, it is likely the result of surname changes among married female providers.

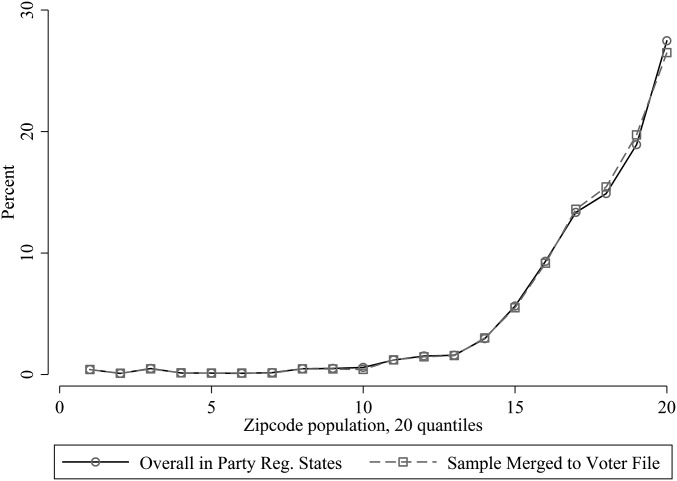

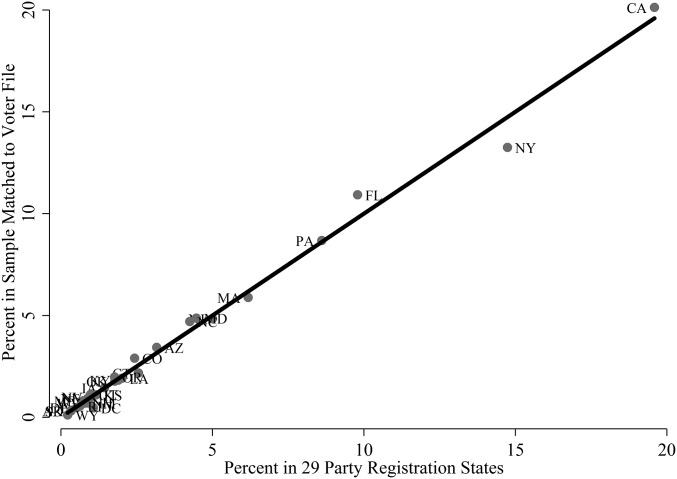

Three graphs speak to the representativeness of the matched physicians. Each of these figures compares the 92,831 physician transmitted to Catalist (weighted to recover the population distribution of all physicians in the NPI file in the 29 party registration states) with the 53,610 physicians who matched to unique records in Catalist (also weighted). In other words, for these graphs, we are showing all records sent to Catalist, not just those in the study of PCPs.

Fig. S1 shows the comparison of specialties. With one exception, the physicians who matched to Catalist reflect the same distribution of specialties as the population. For example, internal medicine doctors make up 14.6% of all physicians in party registration states and 14.1% of physicians who linked to unique records in Catalist. The only outlier here are physicians whose specialty is listed as student. This is likely attributable to (i) the lower rate of registration among younger people and (ii) higher rate of residential mobility among those listed as students.

Fig. S2 shows the distribution of the state that is listed for each physician's practice address on the NPI file. Again, the points all fall very close to the 45° line that indicates perfect representativeness. There is no indication that physicians are more difficult to match in larger states like California, New York, Florida, and Pennsylvania than in smaller states.

Fig. S2.

Work state of physicians in NPI file vs. physicians in NPI-Catalist–matched sample.

Finally, Fig. S3 speaks to the ability to match physicians in high-population zip codes. We divided US zip codes into 20 quantiles based on population. For instance, the first quantile represents the 5% of zip codes with the smallest populations. Fig. S3 calculates the percentages of physicians' work addresses listed in each of these zip codes. For example, 27% of physicians have work addresses in the 5% of zip codes with the high populations. As the figure shows, the distribution of physicians who matched to registration records parallels the distribution of physicians in the population.

Acknowledgments

For outstanding research assistance, we thank Jane Strauch. For helpful advice, we thank Peter Aronow, Adam Bonica, Zach Cooper, Deborah Erlich, Mark Friedberg, Shira Fischer, Jacob Hacker, Ben Hagopian, John Henderson, Dan Hopkins, Greg Huber, and Kelly Rader. E.D.H. thanks Yale University’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies for financial support. M.N.G. thanks Yale University's Department of Psychiatry for financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1606609113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1. Wollschlaeger v. Governor of Florida, 797 F. 3d 859 (US Ct. App., 11th Cir. 2015)

- 2.Wennberg JE. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: Implications for academic medical centres. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):961–964. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krähenmann-Müller S, et al. Patient and physician gender concordance in preventive care in university primary care settings. Prev Med. 2014;67:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall WJ, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–e76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce L, Rogers T, Snyder JA. Losing hearts: The happiness impact of partisan electoral loss. J Exp Pol Sci. 2015;3(1):44–59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber AS, Huber GA. Partisanship and economic behavior. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2009;103(3):407–426. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson A, Goel S, Huber G, Malhotra N, Watts DJ. Political ideology and racial preferences in online dating. Sociol Sci. 2014;1:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyengar S, Westwood SJ. Fear and loathing across party lines. Am J Pol Sci. 2015;59(3):690–707. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Human Rights Campaign 2015 Coming Out to Your Doctor. Available at www.hrc.org/resources/coming-out-to-your-doctor. Accessed December 28, 2015.

- 10.American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2016 Pro-Life OB/GYN Directory. Available at aaplog.wildapricot.org/directory. Accessed January 5, 2016.

- 11.Kaiser Family Foundation The Commonwealth Fund 2015. Experiences and Attitudes of Primary Care Providers Under the First Year of ACA Coverage Expansion. Issue Brief (The Commonwealth Fund, New York), Publication 1823, Vol 17, pp 1–21.

- 12.Bonica A, Rosenthal H, Rothman DJ. The political polarization of physicians in the United States: An analysis of campaign contributions to federal elections, 1991 through 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1308–1317. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank E, Carrera J, Dharamsi S. Political self-characterization of U.S. medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4):514–517. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2(2):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Post RE, et al. The influence of physician acknowledgment of patients’ weight status on patient perceptions of overweight and obesity in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):316–321. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albright TL, Burge SK. Improving firearm storage habits: Impact of brief office counseling by family physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(1):40–46. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peabody JW, et al. Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: A prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):771–780. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachenmeier DW, Rehm J. Comparative risk assessment of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and other illicit drugs using the margin of exposure approach. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8126. doi: 10.1038/srep08126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer G. 2003. About response rates. Public Perspective 2003(May/June):16–18.

- 20.McGhee E, Krimm D. Party registration and the geography of party polarization. Polity. 2009;41(3):345–367. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersh ED, Nall C. The primacy of race in the geography of income-based voting. Am J Pol Sci. 2015;60(2):289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hersh ED. Hacking the Electorate. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hersh ED. Long-term effect of September 11 on the political behavior of victims’ families and neighbors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(52):20959–20963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315043110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau 2012 Reported voting and registration, by sex and single years of age, November 2012. Voting and Registration. Available at www.census.gov/hhes/www/socdemo/voting/publications/p20/2012/tables.html. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- 25.Pew Research Center . Scientific Achievements Less Prominent Than a Decade Ago. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence 2015 The Brady Campaign State Scorecard, March 2015. Available at www.crimadvisor.com/data/Brady-State-Scorecard-2014.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2016.