Significance

Stable isotopes of nitrate have long provided a tool for tracking environmental sources and biological transformations. However, divergent interpretations of fundamental nitrate isotope systematics exist among disciplinary divisions. In an effort to transcend disciplinary boundaries of terrestrial and marine biogeochemistry, we use a quantitative model for coupled nitrogen and oxygen isotopes of nitrate founded on benchmarks established from microbial cultures, to reconcile decades of nitrate isotopic measurements in freshwater and seawater and move toward a unified understanding of cycling processes and isotope systematics. Our findings indicate that denitrification operates within the pervasive context of nitrite reoxidation mechanisms, specifically highlighting the relative importance of nitrification in marine denitrifying systems and anammox in groundwater aquifers.

Keywords: nitrate, nitrification, denitrification, isotopes, anammox

Abstract

Natural abundance nitrogen and oxygen isotopes of nitrate (δ15NNO3 and δ18ONO3) provide an important tool for evaluating sources and transformations of natural and contaminant nitrate (NO3−) in the environment. Nevertheless, conventional interpretations of NO3− isotope distributions appear at odds with patterns emerging from studies of nitrifying and denitrifying bacterial cultures. To resolve this conundrum, we present results from a numerical model of NO3− isotope dynamics, demonstrating that deviations in δ18ONO3 vs. δ15NNO3 from a trajectory of 1 expected for denitrification are explained by isotopic over-printing from coincident NO3− production by nitrification and/or anammox. The analysis highlights two driving parameters: (i) the δ18O of ambient water and (ii) the relative flux of NO3− production under net denitrifying conditions, whether catalyzed aerobically or anaerobically. In agreement with existing analyses, dual isotopic trajectories >1, characteristic of marine denitrifying systems, arise predominantly under elevated rates of NO2− reoxidation relative to NO3− reduction (>50%) and in association with the elevated δ18O of seawater. This result specifically implicates aerobic nitrification as the dominant NO3− producing term in marine denitrifying systems, as stoichiometric constraints indicate anammox-based NO3− production cannot account for trajectories >1. In contrast, trajectories <1 comprise the majority of model solutions, with those representative of aquifer conditions requiring lower NO2− reoxidation fluxes (<15%) and the influence of the lower δ18O of freshwater. Accordingly, we suggest that widely observed δ18ONO3 vs. δ15NNO3 trends in freshwater systems (<1) must result from concurrent NO3− production by anammox in anoxic aquifers, a process that has been largely overlooked.

The advent of the Haber–Bosch process late in the 19th century initiated an unprecedented increase in anthropogenic loading of reactive nitrogen (N) to the biosphere, setting into motion cascades of environmental impacts, including eutrophication and hypoxia, ecosystem acidification, and loss of biodiversity (1). This intensification of environmental N release from agricultural and industrial activities, power generation, municipal and septic wastewater, and domestic fertilizer has tremendously altered the global N cycle, effectively doubling annual global N turnover (1). In groundwater, the most common nitrogenous contaminant is nitrate (NO3−), with recognized and long-term effects on both human and ecological health. Thus, control and elimination of NO3− contamination are priorities of environmental and health agencies worldwide. Despite its significance to global health and ecosystem function, identifying sources of NO3−, tracing its dispersal and attenuation, and gauging its ecological impact remain challenging.

Mitigation of NO3− pollution has necessitated identification of its sources and hydrologic flow paths to monitor the fate and natural attenuation processes occurring in pollutant plumes. To this end, the natural abundance stable isotope ratios of nitrogen (15N/14N) and oxygen (18O/16O) in NO3− have provided an invaluable tool to differentiate sources, track their distribution, and determine the biogeochemical transformations acting on NO3−. By convention, isotope ratios are reported using δ notation, where δ15N = ([15N/14N]sample/[15N/14N]air − 1) × 1,000 and δ18O = ([18O/16O]sample/[18O/16O]VSMOW − 1) × 1,000, in units of per mille (‰). Given two isotopic tracers for a single compound, this approach can be powerful, as each isotope system provides complementary information on sources and biogeochemical transformations (2). Accurate interpretation of isotope distributions, however, strongly hinges on knowledge of the isotope composition of source terms and on a rigorous understanding of isotopic discrimination associated with biological transformations of N pools. The isotopic discrimination associated with specific N transformations is quantified by the isotope effect, ε, where ε (‰) = [(lightk/heavyk) − 1] × 1,000, and k refers to the respective specific reaction rate constants of light and heavy isotopologues (3). Although many of the important source terms and isotope effects of the N cycle are constrained, some remain equivocal. In particular, recent observations emerging from bacterial and archaeal cultures and from incubations of environmental samples have uncovered isotopic discrimination trends for NO3− isotopes that appear at odds with trends typically ascribed to analogous biological transformations in soils and aquifers (4–14). This development has led to conflicting environmental interpretations, reflecting a lack of consensus on fundamental isotope systematics of the processes driving the N cycle. Importantly, the discrepancies between isotopic trends in environmental systems and those from culture-based observations raise the possibility that biogeochemical N dynamics inferred from environmental NO3− isotopic measurements reflect more complexity than previously realized.

Conventional interpretation schemes for NO3− isotopes differ from culture observations with regard to the isotope systematic of denitrification, the stepwise reduction of NO3− to NO2− (nitrite), nitric oxide, nitrous oxide, and finally N2 by heterotrophic bacteria, which is the dominant loss term of reactive N from the biosphere. Early studies of NO3− isotope dynamics in groundwater documented parallel enrichment of δ15N and δ18O of NO3− in association with NO3− attenuation from denitrification, approximating a linear trajectory with a slope 0.5–0.8 (15–17). Indeed, this salient trend has long been considered a unique diagnostic signal of denitrification (2). However, following the advent of the denitrifier method (18, 19), measurements in cultures of both freshwater and marine denitrifying bacteria revealed dual isotope enrichments associated with assimilatory and dissimilatory NO3− consumption systematically following linear trajectories of ∼1 (9, 10, 12, 19, 20), contrasting with the lower values widely observed in freshwater systems. This invariant coupling of N and O isotopic enrichments has been shown to originate from fractionation during enzymatic bond-breakage (8, 21, 22), confirmed directly from in vitro enzyme studies of eukaryotic assimilatory and prokaryotic dissimilatory NO3− reductases (11, 23).

Interpretation schemes conventionally ascribed to nitrification are also at odds with isotope systematics uncovered in culture observations. Nitrification refers to the sequential oxidation of ammonia (NH3) to NO2− then NO3− by chemoautotrophic bacteria and archaea, coupled to aerobic respiration. Oxidation of NO2− to NO3− also occurs during the anaerobic oxidation of NH3 to N2 by anammox bacteria (24). Nitrification constitutes the sole biological production term for NO3−. The NO3− δ18O values reportedly produced by nitrification in freshwater lakes and aquifers span a contended range of 30‰, from −15‰ to 15‰ (2, 25), attributed to the origin of the oxygen atoms appended to NH3 during the two-step process of nitrification: the biological oxidation of NH3 to NO2− incorporates one oxygen atom from molecular O2 and one from water (7, 26, 27); the subsequent oxidation of NO2− to NO3− incorporates an O atom derived from water (28). Recent work, however, has revealed kinetic isotope effects associated with enzymatic incorporation of each of the three O atoms into the product NO3− (5, 6), as well an inverse kinetic isotope effect on the reactant NO2− during oxidation to NO3− (4) and the isotopic equilibration of O atoms between NO2− and water (29, 30). These isotope effects have traditionally not been considered in interpreting NO3− isotope distributions, yet play a fundamental role in defining the isotopic composition of nitrified NO3− in tandem with compositional differences of the O atom sources (7, 13, 31). Thus, moving beyond early studies in which the δ18ONO3 from nitrification was interpreted as a three-part mixture of O atom sources, it is clear that consideration of several isotope fractionation processes is required for accurate interpretation of sources and cycling mechanisms.

To date, observations in marine systems have revealed linear trajectories of ∼1 and trajectories distinctly above the nominal value of 1 associated with water–column denitrification (32–37). Positive deviations from 1 are generally interpreted as reflecting the isotopic imprints of biological NO2− reoxidation superimposed on the trajectory of biological NO3− consumption (34, 38). In freshwater studies, however, this discrepancy between cultures and environment has been scantly acknowledged. Notably, some workers have put forth a number of postulates to explain this conundrum, detailed in S1. Postulates to Explain Deviations from 1 in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N Trajectories in Freshwater. Among these, the biological production of NO3− by nitrifiers occurring in tandem with denitrification has been proposed to account for the apparent differences in δ18O vs. δ15N trajectories between cultures and freshwater environments (39, 40), although this tenet has not been examined specifically. The potential for analogous biogeochemical dynamics to affect isotope distributions in freshwater and marine systems clearly merits exploring.

To arrive at a shared understanding of environmental NO3− isotope systematics, we present the results of a multiprocess numerical model of dual NO3− isotope dynamics parameterized on the basis of fundamental features revealed from culture studies. From this improved understanding of isotopic fractionation during redox cycling of N, we explore implications for NO3− production – by NO2− oxidizing bacteria and by anammox—occurring concurrently with denitrification, specifically focusing on resulting NO3− N and O isotope trajectories. We use this framework to evaluate the potential extent of processes other than unidirectional NO3− consumption by denitrification, which may harbor the key for resolving the discrepancy between decades of groundwater NO3− observations and our physiological understanding of the isotope systematics of microbial N cycling. The scenarios explored herein call attention to the potential influence of N cycling dynamics that have been largely overlooked in aquatic environments and provide a unified framework for future investigations of N isotope biogeochemistry.

2. A Multiprocess Model of NO3− Dual Isotopes: Rationale and Assumptions

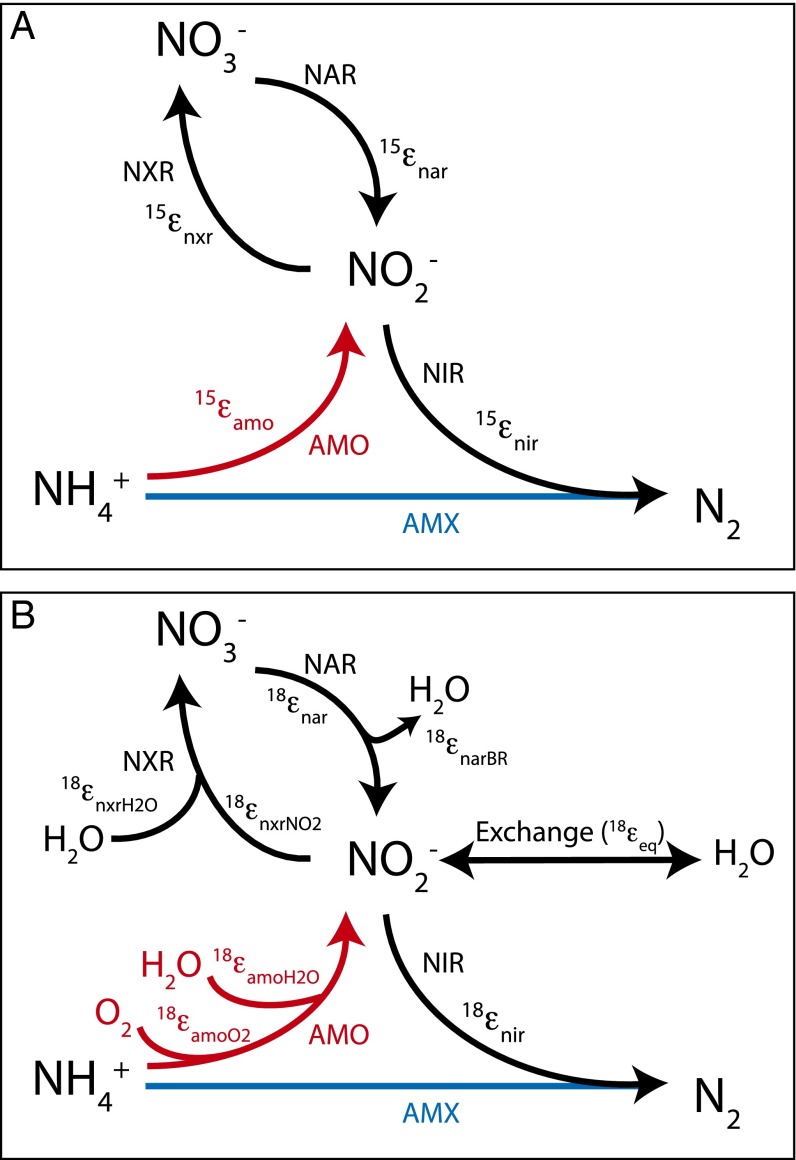

To evaluate the impact of nitrite reoxidation on coupled NO3− N and O isotope trajectories, termed ∆δ18O:∆δ15N henceforth, we devised a time-dependent one-box model simulating the evolution of N and O isotopologue pools of NO3− and NO2− in a closed system during denitrification coincident with aerobic and anaerobic NO2− oxidation by nitrifiers or by anammox bacteria, respectively (Fig. 1; terms defined in Table 1). The isotopologue-specific formulation of the model is described in S2. Equations Used in Time-Dependent NO3− Isotope 1 Box Model.

Fig. 1.

Box model architecture showing N transformations and associated isotope effects influencing (A) δ15NNO3 and (B) δ18ONO3. See text and Table 1 for details and references.

Table 1.

Ranges of parameter values explored in the finite-differencing model exercise, including values prescribed in “standard” model parameterizations

| Initial conditions | Description | Range | Standard | Comment | Reference |

| [NO3−]initial | Initial [NO3−] | 100 µmol/L | 100 µmol/L | ||

| [NO3−]initial | Initial [NO2−] | 0 µmol/L | 0 µmol/L | ||

| δ15NNO3,initial | Initial δ15NNO3 | −10‰ to +15‰ | +5‰ | ||

| δ18ONO3,initial | Initial δ18ONO3 | −10‰ to +15‰ | +5‰ | ||

| δ15NNH4,initial | Initial δ15NNH4 | −20‰ to +15‰ | +5‰ | ||

| δ18OH2O | δ18O of ambient H2O | −20‰ to 0‰ | |||

| 15εnar | N isotope effect for NO3− reduction | +5‰ to +25‰ | +15‰ | Coupled to 18εnar | (9) |

| 18εnar | O isotope effect for NO3− reduction | +5‰ to +25‰ | +15‰ | Coupled to 15εnar | (9) |

| 18εnarBR | Branching O isotope effect for NO3− reduction | 25‰ | 25‰ | (19) | |

| 15εnir | N isotope effect for NO2− reduction | 0‰ to +20‰ | +5‰ | Coupled to 18εnir | (19, 64) |

| 18εnir | O isotope effect for NO2− reduction | 0‰ to +20‰ | 5‰ | Coupled to 15εnir | |

| 15εnxr | N isotope effect for NO2− oxidation by nitrifiers | −35 to 0‰ | −15‰ | (4) | |

| 18εnxrNO2 | O isotope effect for NO2− oxidation by nitrifiers or anammox | −7‰ to −3‰ | −4‰ | (5) | |

| 15εnxrAMX | N isotope effect for NO2− oxidation by anammox | −35‰ | (43) | ||

| 15εnxrAMX’ | NXR-enabled equilibrium isotope effect between NO2− and NO3− | −61‰ | (43) | ||

| 18εnxrH2O | O isotope effect to H2O incorporation by nitrifiers and anammox | +12‰ to +18‰ | +14‰ | (5) | |

| 18εeq | Equilibrium isotope effect between NO2− and H2O | 13.5‰ | 13.5‰ | (30) | |

| 15εamo | N isotope effect for NH3 oxidation by aerobic ammonia oxidation | +26‰* | 26‰* | (41) | |

| 18εamoH2O | O isotope effect for H2O incorporation by aerobic ammonia oxidation | +18‰ to +38‰† | 14‰ | (6) | |

| 18εamoO2 | O isotope effect for O2 incorporation by aerobic ammonia oxidation | +18‰ to +38‰† | 14‰ | (6) | |

| NXR/NAR | Ratio of NO2− oxidation by nitrifiers to NO3− reduction by denitrifiers | 0–0.9 | 0.5 | ||

| AMO/NAR | Ratio of NO2− production by aerobic ammonia oxidation vs. by NO3− reduction | 0–0.9 | 0 |

Not expressed given prescription of complete consumption of the ammonium pool.

The isotope effects of O atom incorporation from O2 and H2O during NH3 oxidation to NO2− have only been determined as a ‘combined’ isotope effect ranging between +18‰ and +38‰ at this time (7). A value of 28‰ was chosen and equally partitioned (+14‰) between the H2O and O2 pools.

In brief, the simulated NO3− pool is influenced by the dissimilative reduction of NO3− to NO2− (NAR) and the concurrent production of NO3− by NO2− oxidation (NXR; Fig. 1). The NO2− pool, in turn, reflects the balance of production by NAR and NH4+ oxidation (AMO), as well as oxidation by NXR and reduction to nitric oxide (NIR). Both reductive processes, NAR and NIR, impart normal N isotope effects, 15εnar and 15εnir, which are equivalent to their corresponding O isotope effects, 18εnar and 18εnir (9, 34). During NAR, a branching isotope effect from O atom abstraction, 18εnarBR (19, 29), also contributes to the δ18O of the NO2− product. In turn, NXR is characterized by inverse kinetic isotope effects for NO2− consumption, 15εnxr and 18εnxr (4, 5), and a normal isotope effect for O atom incorporation from water, 18εnxr,H2O (5). AMO also has normal isotope effects for N, 15εamo (3, 41), and for O atom incorporation from H2O and molecular O2, 18εamo,H2O and 18εamo,O2, respectively (6). However, we assume no accumulation of ammonium (NH4+) from the remineralization of organic material, such that there is no expression of the N isotope fractionation associated with AMO (15εamo), and the NO2− produced by AMO adopts the δ15N of ammonium (δ15NNH4). Finally, NO2− is subject to O isotope equilibration with water having an associated isotope effect, 18εeq (29, 30).

We further consider the potential role of anaerobic NH3 oxidation (anammox), which stoichiometrically produces ∼0.26 moles of NO3− per mole of NH3 oxidized (or per 1.3 moles of NO2− reduced) as a metabolic product from the NO2− pool (24, 42). The model functions as described, except that anammox operates (Fig. 1, blue line) in lieu of aerobic nitrification (Fig. 1, red lines). Notably, unlike in AMO, the δ15N of the NH4+ pool does not enter into the NO3− mass balance during anammox. Similarly, the δ18O of NO3− is not indirectly influenced by NO2− production from NH3, which only occurs aerobically. NO2− oxidation by anammox is prescribed an inverse N isotope effect, 15εnxrAMX (Table 1) (43). Given no constraint from culture work the corresponding O isotope effect, 18εnxrNO2AMX, it is assumed to be of similar magnitude to that for NO2− oxidizers (Table 1). Model parameter ranges are listed in Table 1 and justified in Section 6. For brevity, we also established “standard” model conditions having generally midrange values for isotope effects (Table 1).

3. Model Results

We discuss the contribution of distinct aspects of the reaction network, highlighting those features exerting the most influence on the isotope composition of the evolving NO3− pool, namely, the isotope composition of ambient water and the NO2− oxidation flux. We further explore features that exert moderate influence on coupled NO3− N and O isotope trajectories, including isotope effect values, the isotope composition of initial pools, and NO2− production via biological ammonia oxidation. We then consider scenarios specific to NO3− production by anammox and finally examine the isotope composition of NO2− that emerges among model scenarios. Model results are compared with environmental observations in Section 4.

3.1. Influence of δ18OH2O.

Initial tests were parameterized using standard conditions (Table 1) to explore the sensitivity of the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory to the δ18O of ambient water (from −20‰ to 0‰), for a range of relative fluxes of NO2− oxidation (NXR/NAR from 0 to 0.9) and contrasting scenarios of NO2− equilibration with water. For simplicity, we predominantly consider the case of full equilibration of NO2− oxygen isotopes with water, which likely characterizes most freshwater systems, where equilibration is probably rapid relative to biological cycling given the generally low pH (13, 14, 29, 30, 44). In marine denitrifying regions, δ18ONO2 measurements also suggest full isotopic equilibration with water (34, 35), despite the higher pH of seawater (≤8.2). Results for simulations without NO2− isotope equilibration are otherwise presented in the supplements (S3. Simulation Without Isotope Equilibration of NO2− with Water and Fig. S1).

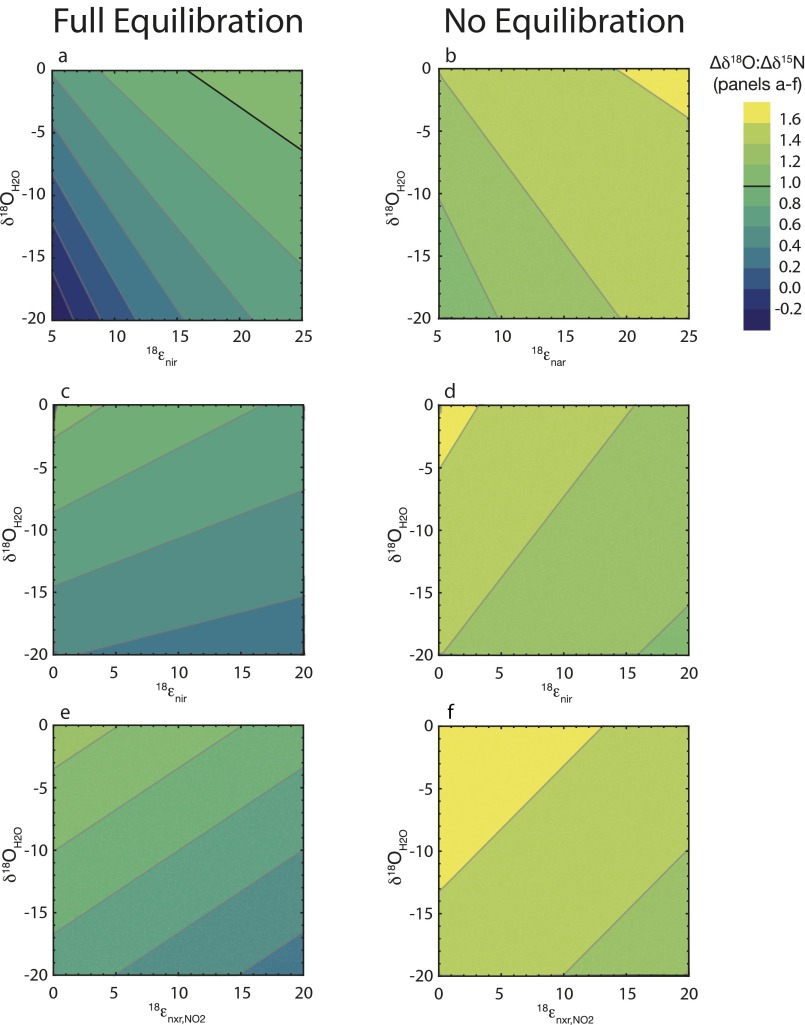

Fig. S1.

Predicted evolution of NO3− ∆δ18ONO3 (δ18ONO3 – δ18ONO3,initial) plotted on the corresponding ∆δ15NNO3 (δ15NNO3 – δ15NNO3,initial) associated with net denitrification coincident with NO3− production by nitrification. Simulations derive from standard model conditions (Table 1) for incremental prescriptions of NXR/NAR (A–C) and of δ18OH2O (colors), without oxygen isotopic equilibration of NO2− with water.

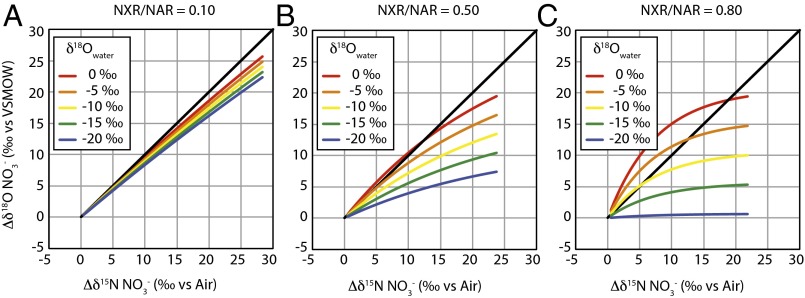

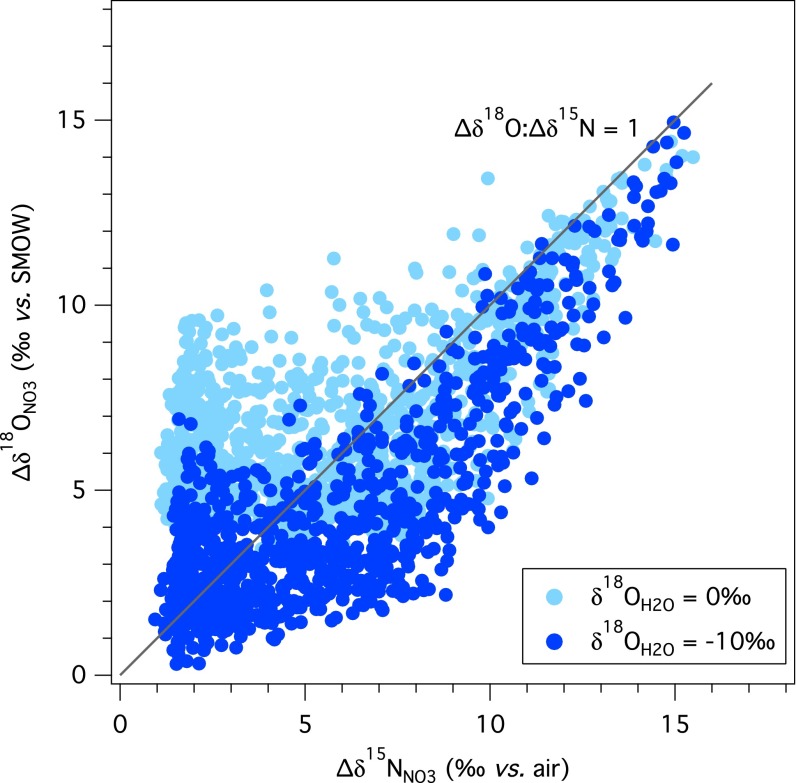

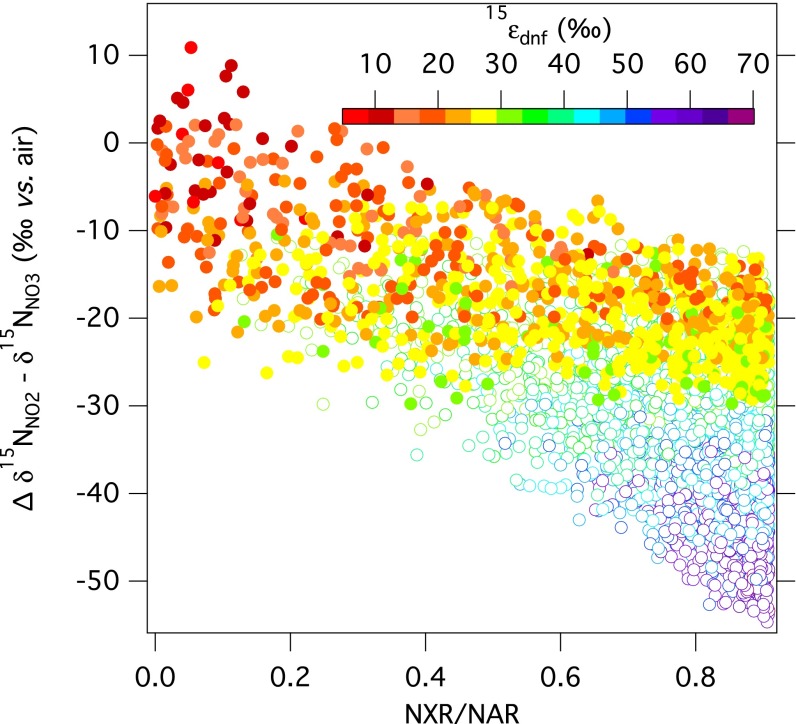

Foremost, results reveal that the evolution of the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory during net denitrification can be substantially deflected from a value of 1 by a co-occurring contribution of newly nitrified NO3− (Fig. 2). Resulting ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories correspond to a broad range of solutions, from 0.1 to 3.2 (in terms of linear fits relating the dual isotopic composition of initial NO3− to that of any evolved modeled composition), of which a larger share yields slopes below the canonical value of 1.

Fig. 2.

Predicted evolution of NO3− ∆δ18ONO3 (δ18ONO3 – δ18ONO3,initial) plotted on the corresponding ∆δ15NNO3 (δ15NNO3 – δ15NNO3,initial) associated with net denitrification coincident with NO3− production by nitrification. Simulations derive from standard model conditions (Table 1) for incremental prescriptions of NXR/NAR (A–C) and of δ18OH2O (colors), for full oxygen isotopic equilibration of NO2− with water.

In all cases, the water δ18O emerges as a strong determinant of the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory: the lowest trajectories are associated with the lowest δ18OH2O and the highest trajectories with the highest δ18OH2O (Fig. 2). Mechanistically, the δ18O of nitrified NO3− is directly related to the water δ18OH2O through both O isotope equilibration of intermediate NO2− and the incorporation of an O atom from water during NO2− oxidation. Under conditions of full isotopic equilibration of NO2−, ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories are thereby insensitive to incorporation of O atoms from water or O2 during any oxidation of NH3 to NO2−. The ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories below 1 are associated with relatively lower δ18OH2O values that contribute to lower δ18O values for nitrified NO3− (Fig. S2). By comparison, the few model solutions in which ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories are above 1 at standard conditions are associated with higher δ18OH2O values, characteristic of marine systems. Conversely, lower δ18OH2O values, characteristic of freshwater systems, are largely associated with ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories below 1.

Fig. S2.

Predicted evolution of the δ18O vs. the δ15N of nitrified NO3− produced from the oxidation of NO2− concurrently with denitrification (Fig. 2). Simulations from standard model conditions (Table 1) for incremental prescriptions of NXR/NAR (right to left) and of δ18OH2O (colors), and for full vs. negligible oxygen isotopic equilibration of NO2− with water (dotted vs. full color lines). The black line delineates the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory for denitrification given no addition of NO3− from nitrification (and/or anammox).

3.2. Importance of the NO2− Oxidation Flux.

Given its importance in linking the composition of water with that of the evolving NO3− pool, the extent to which NO3− is produced relative to that reduced (expressed as NXR/NAR) is also clearly an influential driver of ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory. However, this flux is central not only because it governs the extent to which nitrified NO3− is added back to the NO3− pool, but also because it modulates the δ15NNO3 returned to the NO3− pool. The influence of NXR/NAR on the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory can be summarized as follows (Fig. 2): when NO2− oxidation is nearly equal to NO3− reduction (NXR/NAR ≥ 0.8), the δ15NNO3 produced by nitrification converges on that removed by denitrification (notwithstanding the contribution to the NO2− pool from AMO; S4. Impact of NO3− Production by AMO), thus nearly “restoring” the δ15N of the NO3− pool to its original value. In turn, the δ18O of nitrified NO3− is insensitive to NXR/NAR, deriving primarily from the δ18OH2O when NO2− is fully equilibrated, such that it can be either higher or lower than the δ18ONO3 removed by denitrification depending on the δ18OH2O. Thus, the largest excursions in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories, both above and below 1, occur at the higher values of NXR/NAR. In this respect, trajectories above 1, characteristic of marine denitrifying systems, congruently arise at elevated δ18OH2O.

When NXR/NAR ratios are low (Fig. 2A), the transient NO2− pool is mostly reduced to NO rather than oxidized to NO3−, rendering the δ15N of the NO2− pool relatively more 15N-enriched due to isotopic discrimination by 15εnir. The NO3− produced from the oxidation of NO2− is further 15N-enriched by the inverse effects of 15εnxr. Therefore, the δ15N of nitrified NO3− will be greater than that removed by denitrification, driving the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories to values below 1. The corresponding δ18O of nitrified NO3− (again insensitive to the prescribed NXR/NAR ratio due to full isotopic equilibration of NO2−; Fig. S2) either counters or otherwise augments the negative offset in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N from 1 imposed by the δ15NNO3 of nitrified NO3− depending on the δ18O of this nitrified NO3− (and thus, the δ18O of water). Regardless, all ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories remain below 1 at low NXR/NAR ratios (Fig. S3), even for δ18OH2O values characteristic of seawater.

Fig. S3.

Predicted NO3− ∆δ18ONO3 (δ18ONO3 – δ18ONO3,initial) plotted on the corresponding ∆δ15NNO3 (δ15NNO3 – δ15NNO3,initial) associated with net denitrification and concurrent NO3− production by nitrification in relation to (A) 15εnar (all solutions), (B) 15εnar, (C) NXR/NAR, (D) 15εnir, (E) 15εnxr, and (F) δ15NNO2-NO3. Gray points indicate invalid 15εdnf solutions that exceed 30‰, where 15εdnf is derived from the change in δ15NNO3 vs. the fraction of NO3− remaining. Discrete simulations derive from randomized sets of boundary conditions encompassing the parameter ranges in Table 1 where δ18OH2O = −10‰ and NO2− is fully equilibrated with water.

3.3. Influence of N and O Isotope Effects.

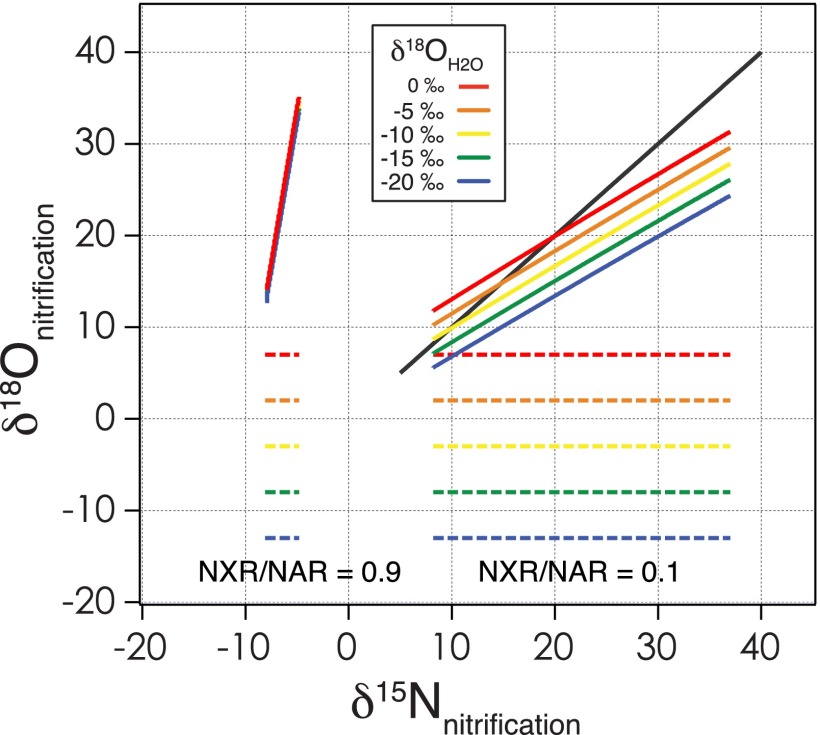

To investigate the leverage of specific isotope effects on the evolving ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories, we examine the response of NO3− trajectories while holding all other parameters constant (standard conditions; Table 1), plotting them against δ18OH2O as a master variable (Fig. 3), given its central role in the composition of nitrified NO3− as described above.

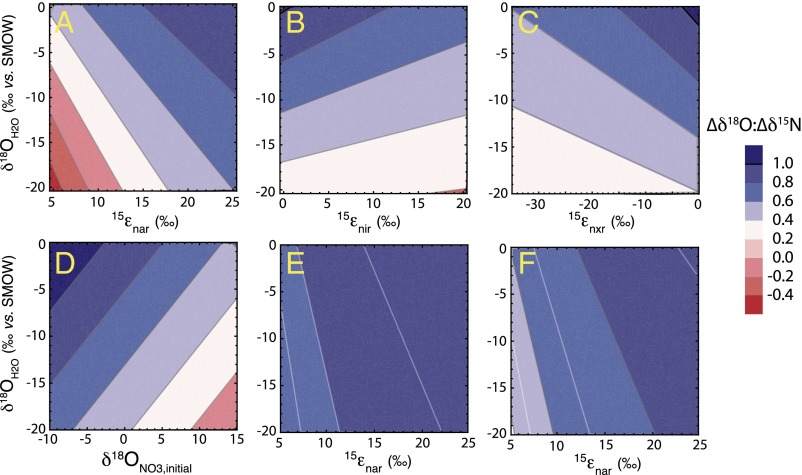

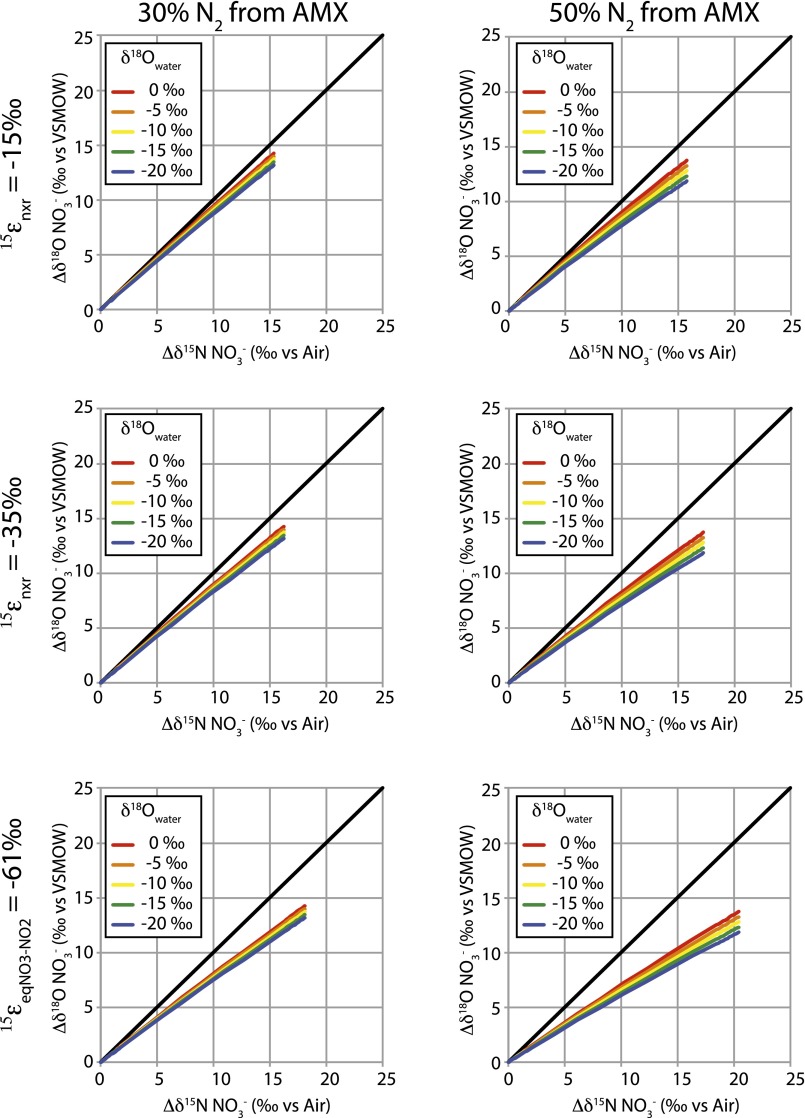

Fig. 3.

Predicted NO3− ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (represented as the apparent linear slope calculated with respect to the initial NO3− isotope composition; color scale) associated with net denitrification and coincident NO3− production for a range of δ18OH2O given full oxygen isotopic equilibration of NO2−, plotted over (A) 15εnar, (B) 15εnir, (C) 15εnxr, and (D) δ15NNO3,initial. Trajectories plotted over 15εnar for NO3− production by anammox only for (E) 30% of total N2 production by anammox and for (F) 50% N2 production by anammox, with 15εnirAMX = 20‰, and 15εnxrAMX = −35‰. Parameter values are otherwise anchored at standard conditions (Table 1).

Results indicate that the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory increases progressively with increasing 15εnar, the N isotope effect of nitrate reduction (Fig. 3A). This dynamic is best understood by considering the influence of 15εnar on the composition of the transient NO2− pool subject to reoxidation to NO3−. The δ15NNO2 returned to the NO3− pool by nitrification is more 15N-depleted at higher 15εnar values, tending to more elevated ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories. However, although trajectories above 1 emerge more readily at higher prescribed 15εnar, the majority of these solutions are not viable, resulting in observed (or apparent) isotope effects for denitrification (15εdnf, derived from the change in δ15NNO3 relative to the fraction of NO3− removed) substantially higher than the empirical maximum of ∼30‰ observed in the environment (Fig. S3). This dynamic arises because the N isotope effects for NO2− reduction (15εnir), NO2− oxidation (15εnxr), and the NXR/NAR flux ratio amplify the 15N-enrichment of the NO3− pool relative to its consumption beyond that imparted specifically by 15εnar, thus increasing apparent values of 15εdnf. Thus, viable solutions (i.e., 15εdnf ≤ 30‰) for ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1 emerge predominantly at 15εnar amplitudes of ≤15‰. Conversely, viable solutions stemming from more elevated 15εnar amplitudes are only produced at relatively low NO3− production (NXR/NAR), corresponding to ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories close to 1. Therefore, ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1, characteristic of marine denitrifying systems, and of ∼0.6 for freshwater systems, do not result at high 15εnar values, suggesting that the organism-level isotope effect for denitrification (15εnar) in environmental settings is generally not as high as the 15εnar of ∼25‰ often observed in culture conditions (10) (Section 4).

The amplitude of 15εnir for the reduction of NO2− also modulates the isotopic evolution of the NO3−, with higher 15εnir (coupled here to 18εnir) corresponding to lower ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (Fig. 3B). Stronger 15N discrimination during NO2− reduction to NO acts to increase the δ15N of the NO2− pool, thereby increasing the δ15N of NO3− produced from any oxidation of NO2− and lowering the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory (Fig. S3).

The amplitude of the inverse isotope effect prescribed to 15εnxr also has an important influence on the δ15NNO3 of newly nitrified NO3−. Lower 15εnxr values (i.e., more negative) give rise to lower δ15NNO2, countered by production of correspondingly higher δ15NNO3, thereby acting to lower the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory (Fig. 3C). Conversely, less negative 15εnxr amplitudes produce NO3− having a relatively lower δ15N, leading to higher ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories.

In the model, 18εnar is, by design, equivalent to the corresponding 15εnar. As such, its influence on ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories appears identical to 15εnar (Fig. S4A). This congruence, however, is only incidental because the δ18ONO2 produced from NO3− reduction is entirely erased given full isotopic equilibration of NO2− with water. Therefore, 18εnar actually has no bearing on the δ18O of newly nitrified NO3−. Similarly, the oxygen isotope effect for NO2− reduction, 18εnir, also has an apparent influence on the NO3− ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory related to its coupling with the corresponding 15εnir (Fig. S4C). Here again, however, any increase in the δ18ONO2 imposed by its reduction to NO is ultimately erased due to isotopic equilibration of the NO2− with water, such that the value of 18εnir is inconsequential to the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory.

Fig. S4.

Predicted NO3− ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (color scale) associated with net denitrification and coincident NO3− production for a range of δ18OH2O plotted over (A and B) 18εnar, (C and D) 18εnir, and (E and F) 18εnxrNO2. Simulations include full oxygen isotopic equilibration of NO2− with water (Left) or no oxygen isotopic equilibration of NO2− (Right) at standard conditions (Table 1).

In contrast, the amplitude of 18εnxrNO2 does affect the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory because the influence of 18εnxrNO2 occurs downstream of NO2− equilibration. Given this inverse isotope effect, lower (more negative) values of 18εnxrNO2 are associated with an increase in the δ18O of newly nitrified NO3−, and consequently, a relative increase in corresponding ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (Fig. S4E). However, the influence of 18εnxrNO2 on ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories is generally muted because 18εnxrNO2 only affects two-thirds of the O atoms in the newly nitrified NO3− and because the corresponding 15εnxr has a greater amplitude than 18εnxrNO2 (Table 1) but opposing influence on ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories.

Finally, the isotope effect associated with the incorporation of an O atom from water during NO2− oxidation, 18εnxrH2O, also plays a role in determining the δ18O of nitrified NO3−. As prescribed, the δ18O of the O atom incorporated from water during NO2− oxidation is ∼14‰ lower than that of ambient water, thus contributing a lower δ18O than that from the two oxygen atoms in NO2−. Because the amplitude of 18εnxrH2O has so far proven to be relatively invariant among cultures and experimental strains (5, 7), we do not consider variations of this value on ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories.

3.4. Initial Isotope Composition of the NO3− Pool.

The initial isotopic composition of NO3− is also linked to the evolution of its dual isotopic trajectory during net consumption coupled with contemporaneous production. Under conditions of a fully equilibrated NO2− pool, this dependence stems chiefly from the difference between the δ18ONO3 and the δ18OH2O. Mechanistically, the difference in δ18O values between NO3− and water imposes a corresponding difference between the δ18ONO3 removed by NO3− reduction and the δ18ONO3 returned to the NO3− pool by NO2− oxidation, in relation to the δ15NNO3 concurrently being removed and returned.

For nearly all combinations of model conditions, the δ15NNO3 added by nitrification is greater than that removed concurrently by denitrification, owing to the compounding influences of isotope effects associated with NO2− reduction (normal) and oxidation (inverse), 15εnir and 15εnxr. On its own, the higher δ15N of nitrified NO3− thus tends to lower the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory from a value of 1 for most model conditions.

The δ18ONO3 produced by nitrification either counters or otherwise amplifies the negative deviations from a ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory of 1 imposed by the corresponding δ15NNO3. When the initial δ18ONO3 is nearer to the δ18OH2O, the δ18ONO3 produced during nitrification is higher than that removed by denitrification, such that the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory increases (Fig. 3D). Conversely, when the initial δ18ONO3 is elevated relative to the δ18OH2O, denitrification removes a δ18ONO3 that is similar to, or greater than, that added by nitrification, contributing further to a decrease in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory from a value of 1 imposed by corresponding δ15NNO3 dynamics.

The difference in δ18O between water and NO3− thus provides a first order rule of thumb to explain the magnitude of the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory. For instance, in marine systems, the difference between the δ18O of subsurface NO3− (≥2‰) and seawater (∼0‰) is small. At any value of 18εnar, the δ18O of nitrified NO3− is greater than the δ18ONO3 removed by denitrification, thus generating ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1 for numerous model conditions (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5). In contrast, in freshwater systems, the difference between the δ18O of NO3− and water can be large (e.g., δ18ONO3 of +20‰ and δ18OH2O of −10‰ would not be unusual), such that the δ18O of nitrified NO3− tends to be similar to, or can be lower than, the δ18ONO3 removed by denitrification, promoting ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories below 1 under most conditions (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5). In this light, ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above a nominal value of 1 have an intrinsically greater likelihood of emerging in marine systems, whereas trajectories below 1 are more likely for freshwater systems.

Fig. S5.

Predicted NO3− ∆δ18ONO3 (δ18ONO3 – δ18ONO3,initial) plotted on the corresponding ∆δ15NNO3 (δ15NNO3 – δ15NNO3,initial) for δ18OH2O = 0‰ vs. -10‰. Discrete simulations derive from randomized sets of boundary conditions for parameter ranges in Table 1, with full oxygen isotopic exchange of NO2−, AMO/NXR = 0, δ15NNO3,initial = 5‰, and δ18ONO3,intial = 0‰, where 15εdnf ≤ 30‰ (15εdnf is derived from the change in δ15NNO3 vs. the fraction of NO3− remaining).

3.5. Influence of NH3 Oxidation to NO2−.

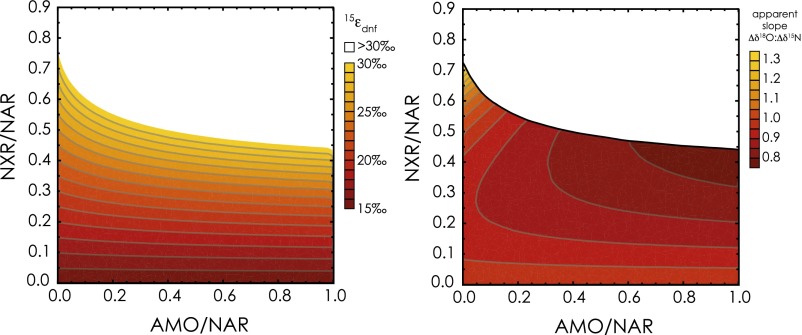

As parameterized, the production of NO2− by AMO yields invalid 15εdnf values (>30‰) at elevated NO2− oxidation fluxes (NXR/NAR ratios ≥ 0.5) while exerting little influence on ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories with lower NO2− oxidation (Fig. S6). For these reasons, we relegate detailed discussion of the impact of AMO to S4. Impact of NO3− Production by AMO.

Fig. S6.

(A) Predicted apparent isotope effect for denitrification, 15εdnf (color scale), as a function of the NO2− production by AMO (AMO/NAR) vs. NO3− production by NXR (NXR/NAR; Fig. 1). (B) Predicted NO3− ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (color scale) as a function of AMO/NAR vs. NXR/NAR. Parameter values are anchored at standard conditions (Table 1) and δ18OH2O = 0‰. White region represents conditions under which predicted values of 15εdnf exceed an empirical maximum of 30‰.

3.6. NO3− Production by Anammox.

To assess whether NO3− production by anammox is potentially sufficient to induce departures of ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories from a value of 1, we consider two scenarios, the first in which anammox rates are bounded by the organic matter remineralization stoichiometry of denitrification, and the second in which anammox rates contribute an equal proportion of the N2 flux relative to denitrification (45). In the first scenario, anammox rates are controlled by NH4+ supplied only from the decomposition of organic material coupled with NO3− respiration, wherein the release of 1 mol of NH4+ from organic matter requires respiration of 5.9 mol of NO3− to N2 (46). Each mole of NH4+ then reacts with 1 mol NO2− (produced transiently by denitrification) to form N2 (24, 42). Concurrently, an additional 0.3 mol NO2− is returned to the NO3− pool (42). Of the total N2 produced, 30% originates from anammox and the rest from canonical denitrification. The oxidation of NO2− by anammox therein corresponds to a relatively small NXR/NAR flux ratio of 0.05.

The ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories generated from these model conditions are consistently below 1, regardless of δ18OH2O (Fig. 3E). In this respect, trajectories as low as 0.6, characteristic of freshwater system, are only attained with prescriptions of relatively low 15εnar of ≤5‰. Thus, within this scenario, anammox can only explain excursions in freshwater ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories assuming specifically low values of 15εnar.

When the anammox rate is parameterized to account for 50% of N2 production, the corresponding NXR/NAR flux ratio increases to ∼0.1 and ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories are on the order of ∼0.6 for a relatively broader ranges of 15εnar amplitudes (Fig. 3F). Therefore, if anammox rates in freshwater systems are not strictly bounded by ammonification coupled to NO3− respiration—namely, if NH4+ is also released via de-sorption from clays (47, 48) or from organic matter degradation pathways fueled by fermentation or other oxidants [e.g., Fe(III), Mn(III/IV)]—the production of NO3− by anammox could easily account for ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories of 0.6 commonly observed in freshwater systems.

The amplitude of 15εnxrAMX is subject to some uncertainty. A recent study showed that enrichment cultures of anammox produced NO3− with a δ15NNO3 ∼61‰ greater than corresponding δ15NNO2 following initial resuspension of cells (interpreted as an “enzyme-catalyzed equilibrium isotope effect” between NO3− and NO2−), after which NO3− production was associated with a 15εnxrAMX amplitude of −35‰ (43). Accordingly, if NO3− produced by anammox had a δ15N ∼61‰ greater than that of corresponding NO2−, then an even smaller contribution of NO3− from anammox would be required to influence ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (Fig. S7). From any perspective, anammox clearly emerges as a compelling candidate to explain negative deviations from ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories of 1 observed in freshwater systems.

Fig. S7.

Predicted evolution of NO3− ∆δ18ONO3 (δ18ONO3 – δ18ONO3,initial) plotted on the corresponding ∆δ15NNO3 (δ15NNO3 – δ15NNO3,initial) associated with net denitrification and coincident NO3− production by anammox. Simulations derive from standard model conditions (Table 1) for discrete contributions of anammox to total N2 production (left vs. right panels), and incremental prescriptions of 15εnxrAMX (top to bottom panels) and δ18OH2O (colors).

Notably, ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories remain below 1 regardless of anammox rate or 15εnxrAMX values, owing to the relatively small NO2− oxidation flux permitted by anammox stoichiometry. By itself, anammox thus fails to reproduce ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1 observed in marine systems. In our model, even if anammox accounts for 100% of N2 production, the corresponding NXR/NAR ratio amounts to a mere 0.23, a value insufficient to generate ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories akin to those observed in oxygen deficient zones, regardless of prescribed 15εnxrAMX amplitudes (Fig. S8). Thus a significant input of NO3− from aerobic NO2− oxidation (or NO2− oxidation coupled to other electron acceptors) is required to explain ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories >1 in oceanic oxygen deficient zones (Section 4.1).

Fig. S8.

Predicted NO3− ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories associated with net denitrification and coincident NO3− production by anammox plotted over % of total N2 production by anammox for (A) δ18OH2O = 0‰ and (B) δ18OH2O = -10‰, in relation to 15εnar (colors). Discrete simulations derive from randomized sets of boundary conditions encompassing the parameter ranges in Table 1, with full oxygen isotopic exchange of NO2−, 15εnirAMX = 20‰, and 15εnxrAMX = −35‰.

3.7. NO2− Isotope Dynamics.

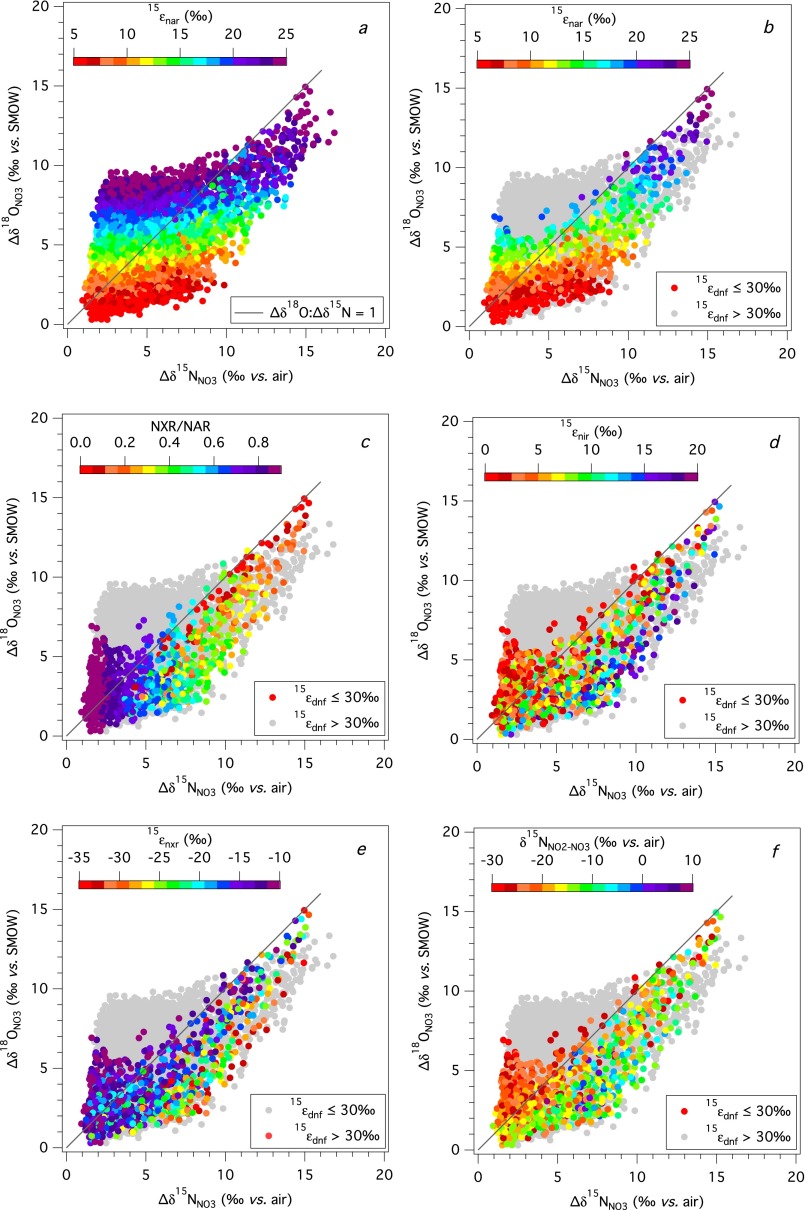

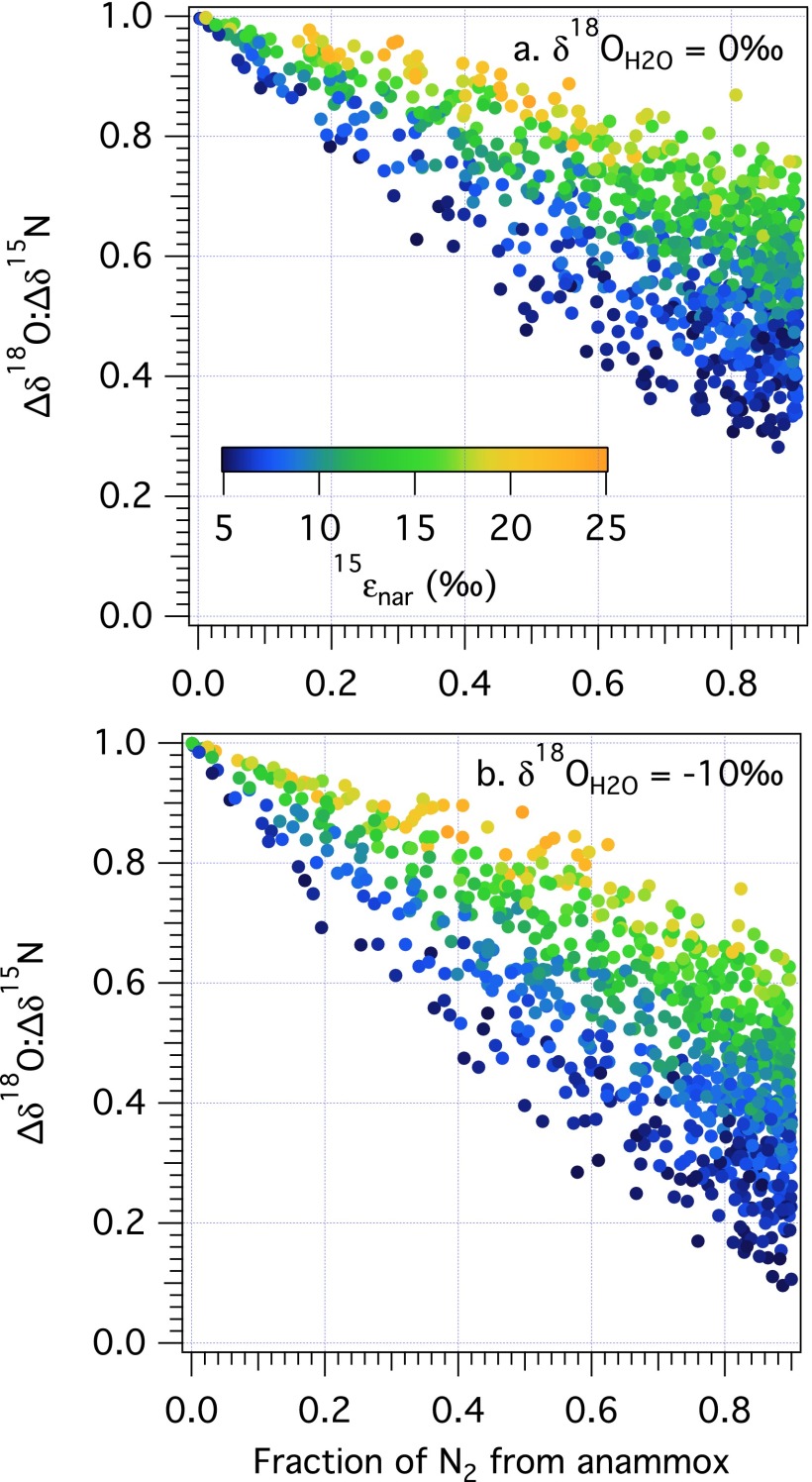

Recent methodological advances enable the direct quantitation of NO2− δ15N and δ18O at environmental concentrations (49, 50), providing a complementary tracer from which to diagnose environmental N cycling. Under conditions examined here, the predicted δ15N of the NO2− pool ranges from 30‰ lower than the corresponding δ15NNO3 (∆δ15NNO2-NO3 = δ15NNO2 − δ15NNO3 = −30‰), to 10‰ greater than the corresponding δ15NNO3 (Fig. 4). In the context of observed ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories, δ15NNO2 emerges as sensitive to the prescribed NXR/NAR flux ratio (Fig. 4 and Fig. S3). Relatively large negative ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 offsets correspond to elevated ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories and elevated NXR/NAR amplitudes. Conversely, more modest ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 values are more prevalent at lower NXR/NAR amplitudes (≤0.2) and ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories below 1. The δ18ONO2, in turn, can provide affirmation that NO2− is equilibrated with water, which we anticipate in freshwater systems, and which has been observed in most denitrifying marine systems (34, 35). Therefore, if measured concurrently with those of NO3− (and ambient water), the δ15N and δ18O of NO2− offer added quantitative constraints on the relative flux of NO2− returned to NO3− pool under denitrifying conditions (29, 30, 33, 34).

Fig. 4.

Predicted difference between δ15NNO2 and δ15NNO3 (∆δ15NNO2-NO3) associated with net denitrification and coincident NO3− production plotted against the NXR/NAR ratio, in relation to 15εdnf (color scale). Discrete simulations derive from randomized parameter ranges (Table 1), with full oxygen isotopic exchange of NO2−, AMO/NAR = 0, δ18OH2O = -10‰, δ15NNO3,initial = 5‰, and δ18ONO3,intial = 0‰. Open symbols correspond to model solutions where 15εdnf > 30‰.

4. Links to Environmental Studies

4.1. Marine Systems.

Discrete lines of evidence suggest that a substantial fraction of the NO2− produced by denitrification in low oxygen zones of the ocean is returned to the NO3− pool by aerobic NO2− oxidation (34, 51, 52). Mechanistically, the redox potential of waters bounding oxygen-deficient zones may be dynamic, responding to periodic advection of oxygenated waters near redox boundaries (51, 53). Evidence that NO2− reoxidation occurs concurrently with denitrification originates in part from observations of ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories exceeding an expected value of 1. Measurements of the δ15N and δ18O of NO3− and NO2− from the Eastern Tropical Pacific and the Peru Upwelling region suggest that NO2− reoxidation is the more likely cause of such patterns (32–34). Specifically, the δ15N of NO2− at the subsurface is 30–40‰ lower than the coincident NO3− δ15N, reaching δ15N values as much as 60‰ lower than the coexisting NO3− (∆δ15NNO2-NO3 = −30 to −60‰). Best fit solutions to an inverse finite-difference model tracking the evolution of NO3− and NO2− isotopes along isopycnals indicated substantial NO2− reoxidation flux, with NXR/NAR ≥ 0.50 (34). Model fits further diagnosed moderate 15εnar values of ∼13‰, 15εnxr values on the order of −30‰, no fractionation during NO2− reduction (15εnir of 0‰), complete oxygen isotope equilibration of NO2− with seawater, and no significant input of NO2− from AMO.

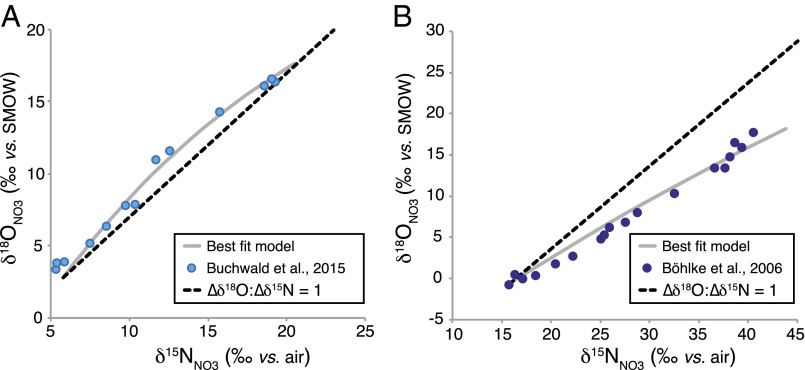

The interpretations of recent observations in marine denitrifying waters generally corroborate the predictions from the model presented here. For illustration, we adapted the model architecture outlined above to use an inverse approach to numerically optimize NO3− isotope measurements along a subsurface isopycnal at the Costa Rica Dome (35) (Fig. 5). The measurements evidenced a progressive NO3− decrease along the isopycnal surface with a concurrent increase in δ15N and δ18O, corresponding to a ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory >1 and an apparent isotope effect, 15εdnf, of 28‰. Values of 15εnar, 15εnir, 15εnxr, and NXR/NAR were numerically optimized, iteratively finding the least squares fit to measured NO3− concentration, δ15N and δ18O, assuming negligible NO2− production by AMO and full equilibration of NO2− with water (S5. Model Inversion). Accordingly, the apparent ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory corresponds to an elevated NXR/NAR flux ratio of 0.64 ± 0.07, and diagnoses of moderate values for 15εnar, 15εnxr, and 15εnir of 14.1 ± 2.3‰, 10.9 ± 4.4‰, and −16.0 ± 4.5‰, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

(A) Best inverse fit ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory describing NO3− δ15N and δ18O in an oceanic oxygen deficient zone in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific (35). Initial NO3− concentrations were interpolated based on the “initial” profiles outside the oxygen deficient zone (35), δ18OH2O = 0‰, and the AMO flux is assumed to be negligible. Best-fit estimates of 15εnar, 15εnir, and 15εnxr are +14.1 ± 2.3‰, +10.9 ± 4.4‰, and −16.0 ± 4.5‰, respectively, with a diagnosed NXR/NAR of 0.64 ± 0.07. Model-predicted Δδ15NNO2-NO3 values are between −20‰ and −22‰ and the apparent isotope effect, 15εdnf, is 28‰. (B) Best inverse fit ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory for NO3− δ15N and δ18O in a contaminated aquifer in Cape Cod, MA (54). Best-fit estimates of 15εnar, 15εnir, and 15εnxr for the ETNP are +10.2 ± 1.3‰, +9.6 ± 4.2‰, and −24.0 ± 7.7‰, respectively, with a diagnosed NXR/NAR of 0.31 ± 0.08, model-predicted Δδ15NNO2-NO3 values between −6‰ and −7‰, and an apparent isotope effect, 15εdnf, of 16‰.

Interestingly, the curvature in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories apparent in our model results (Fig. 2) is substantiated by analogous curvature in dual NO3− isotope trajectories documented in denitrifying ocean waters (34–37) (Fig. 5). The increase of NO3− N and O isotope ratios associated with net denitrification along isopycnals in the subsurface follows apparent ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories distinctly above a nominal slope of 1 that show clear curvature at higher extents of net NO3− consumption. In our model, the degree of curvature increases in proportion to the NO2− oxidation flux (Fig. 2), because the δ15N of nitrified NO3− increases progressively as a function of net NO3− consumption, whereas the corresponding δ18O of nitrified NO3− remains directly dependent on the δ18O of water (Fig. S2). The curvature in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory in our model simulations thus appear validated by analogous patterns in NO3− isotope distributions in marine denitrifying environments.

Anammox has been detected in oxygen minimum zones of the ocean, where its potential contribution to the total N2 flux has generated considerable debate (54–57), with estimates ranging from 30% to 100% of the total N2 flux. The model exercise here suggests that NO3− production by anammox cannot, by itself, explain ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories exceeding 1, given diagnoses of NO2− reoxidation to the NO3− pool that far exceed stoichiometric constraints of anammox. Even if anammox is assumed to account for 100% of N2 production, the corresponding NO2− flux remains insufficient to generate ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1. Accordingly, analyses of NO3− and NO2− isotope ratios in other denitrifying regions of the Pacific and Indian Oceans have converged on similar interpretations, ultimately diagnosing a substantial return flux of NO2− to the NO3− pool catalyzed largely by aerobic nitrification (34–37).

Despite general agreements between model and observations, some aspects remain puzzling. For one, the δ15NNO2 in denitrifying marine waters can be substantially lower than predicted by the current exercise, with ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 values ranging between −30‰ and −60‰ in situ (34, 35), compared with −20% and −30‰ in our model (Fig. 4). Indeed, the best-fit parameters to the Costa Rica Dome data predict corresponding ∆δ15NNO3-NO2 values on the order of −20% to −22‰ (Fig. 5) compared with measured ∆δ15NNO3-NO2 values between −20‰ and −50‰ (35). Lower ∆δ15NNO3-NO2 values can only be generated in the current model framework by assuming an elevated reoxidation to reduction flux (NXR/NAR), as well as large amplitude isotope effects for 15εnar and 15εnxr on the order of 30‰ and −30‰, respectively. However, while realizing ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 values as low as −60‰ and ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1, such simulations result in apparent values of 15εdnf that far exceed the empirical limit of 30‰ (Fig. 4). Otherwise, 15εnxr may be effectively subsumed into an equilibrium isotope effect of −61‰, the purported enzyme-catalyzed equilibrium isotope effect between NO2− and NO3− (43), such that the net production of NO3− by the NO2− oxidoreductase enzyme can generate ∆15NNO2-NO3 values of ∼−60‰, albeit at elevated NXR/NAR flux ratios. This scenario, however, still results in apparent 15εdnf values that far exceed 30‰, thus inconsistent with observations. Arguably, isotopically catalyzed enzymatic isotope equilibration by NO2− oxidoreductase need not be associated with a net oxidative flux. Such a scenario is analogous to simulations here where NXR is nearly equal to NAR (with NAR representing NO3− reduction by NO2− oxidoreductase in lieu of NO3− reductase). The equilibrium isotope effect of −61‰ is then implicitly the sum of the oxidative and reductive isotope effects with respect to NO2−, −31‰ for NO2− oxidation vs. −30‰ for NO2− production from NO3−, wherein the resulting ∆15NNO2-NO3 of the NO2− pool is ∼−60‰. Again, apparent values of 15εdnf emerging from such simulations are unrealistic (on the order of 60‰). Thus, within the current model framework, the putative enzyme-catalyzed equilibrium isotope effect between NO2− and NO3− does not appear to readily explain the very low ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 observed in marine denitrifying systems.

The discrepancy between our modeled ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 and observations may otherwise derive in part from the constant N transformation rates in our simulations, as more negative δ15NNO2 values could be generated within representative model conditions given time/space-variable rates of NO2− accumulation and depletion and/or isotope effects. Nevertheless, inverse fits allowing for time-variable rates of N transformations still implicate 15εnxr values on the order of −30‰ (34, 35), distinctly lower than values observed in nitrifier cultures of –15‰ (5, 7). Additionally, the inverse-model fits are contingent on the diminished expression of 15εnir (5, 7), a diagnosis that is also echoed in our model (Fig. S3). Such low 15εnir amplitudes appear contradictory to expectations from cultures and enzymatic studies (19, 43, 58, 59) and are also inconsistent with some recent field observations (36), where an increase in δ15NNO2 along isopycnal surfaces in a denitrifying eddy at the Peru margin (in which no NO3− remained) was associated with an apparent 15εnir of 12‰. The very low δ15NNO2 observed in marine denitrifying zones thus remains perplexing and merits further inquiry.

4.2. Freshwater Systems.

As demonstrated here, the empirical ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories between 0.5 and 0.8 recurrently observed in freshwater systems can be explained by superimposing the isotopic systematics of denitrification with those of oxidative NO3− production. This dynamic could arise on the premise that redox conditions in aquifers may be dynamic, owing to intercalated microzonation within sediments (60) and/or periodic downward percolation of oxygenated waters. However, nitrifying organisms and their biogeochemical activity are rarely detected at the heart of denitrifying aquifers (61, 62). Thus, in the absence of any O2-requiring transformations, it is likely that any return of NO2− to the NO3− pool in anaerobic aquifers is associated with anammox, the anaerobic oxidation of NH3 coupled to reduction of NO2−, which yields NO3− (as well as N2) as a metabolic product (24, 42). Indeed, recent studies suggest that a substantial fraction of N2 production in aquifers originates from anammox (63–65), rivaling N2 production by canonical denitrification in some instances (45).

We turn to a well-studied site of groundwater contamination on Cape Cod, MA (47), to estimate isotope effects and relative NO2− oxidation rates that could explain NO3− isotope distributions therein. Within the contaminant plume, ∼180 μM NO3− decreased to ∼35 μM along an anoxic groundwater flow path. Concomitant with this decrease in NO3− concentration, pronounced changes in δ15NNO3 and δ18ONO3 were also observed, increasing from ∼+15‰ to +45‰ and from −1‰ to +18‰, respectively, yielding a corresponding ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory of ∼0.73 and an apparent N isotope effect for the observed denitrification, 15εdnf, of ∼16‰ (47). We use the inverse approach outlined above to numerically optimize values of 15εnar, 15εnir, 15εnxr, and NXR/NAR, iteratively finding the least squares fit to measured NO3− concentration, δ15N and δ18O (S5. Model Inversion). We also make a simplifying assumption that AMO is negligible in the anoxic portion of the aquifer. Given the pH and δ18O of groundwater at this site (∼6.5 and −6.5‰, respectively) (47), we also assume that any NO2− will be fully equilibrated with water.

As expected, deviation of the dual isotopic composition from a ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory of 1–0.73 can be accommodated by concomitant production of NO3− along this flow path (Fig. S8). Best-fit solutions yield estimates of 15εnar, 15εnir, and 15εnxr of 10.6 ± 0.2‰, 10.2 ± 3.9‰, and −31.3 ± 7.7‰, respectively. Consistent with expectations, lower actual values of 15εnar are diagnosed (i.e., below the observed 15εdnf of ∼16‰), as the increase in δ15NNO3 is also influenced by NO3− production with a relatively high δ15N via NXR. Under these conditions, the required amount of NO3− production relative to its removal is on the order of 13 ± 0.3% (i.e., NXR/NAR = 0.13), much lower than that predicted by recent dual isotope models of ocean denitrifying zones in which the diagnosed NXR/NAR can be as high as 0.9 (34). Although not measured in the original aquifer study, these best-fit parameters also allow us to predict the δ15N of coexisting NO2−—for which we arrive at ∆δ15NNO2-NO3 values between −6.1‰ and −4.4‰. This prediction of a relatively small δ15N difference between coexisting pools of NO3− and NO2− under aquifer conditions provides a target for future studies and a means for refining our estimates of N cycling in groundwater and other environments.

Notably, the estimated value for 15εnxr of ∼−31‰ for the aquifer is higher than that observed in cultures of NO2− oxidizing bacteria (7), yet largely consistent with that for anammox (43), potentially implicating anammox as an important N removal process in this aquifer. The diagnosis of NXR/NAR ratio of 0.13 corresponds to ∼65% of total N2 production in the aquifer fueled by anammox, a value also consistent with recent independent estimates made in the same aquifer (45). Indeed, given the stoichiometric constraints of NO3− production by anammox, we suggest these model results may prove diagnostic of the role of anammox in ground waters globally.

5. Summary and Conclusions

Foremost, our results demonstrate that deviations from the canonical ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory of 1 for denitrification must emerge due to concurrent NO3− production catalyzed by nitrification and/or anammox, not only in marine systems, but also in freshwater systems, where this tenet has been given limited consideration. Assuming that full O isotopic equilibration of NO2− is pertinent to both freshwater and marine denitrifying systems, our results emphasize the sensitivity of the δ18O of newly produced NO3− to the δ18O of ambient water and the isotope effects for O atom equilibration and incorporation. Trajectories above 1 emerge specifically where the NXR/NAR flux ratio is high (≥0.5) and predominantly where the difference between the δ18O of NO3− and that of water is small. The diagnosis of high NO3− production in the generation of ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1 disputes the notion that anammox could be the sole NO3−-producing reaction in marine denitrifying systems, given stoichiometric and biochemical limitations on the amount of NO2− that anammox can return to the NO3− pool, and thus implicates a significant contribution by aerobic NO2− oxidation.

Importantly, the majority of solutions to randomized combinations of model conditions yield ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories <1 for simulations using a fully equilibrated NO2− pool. In this respect, our analysis of NO3− isotopes from a representative aquifer (47) suggests that the characteristic ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory therein (∼0.73) arises from relatively low NXR/NAR flux ratios (∼0.13), which is well aligned with the stoichiometric and biochemical constraints of anammox. Thus, in addition to the leverage of distinctive δ18OH2O between freshwater and marine systems, characteristic NO3− isotope trends between denitrifying groundwater and marine systems also appear to reflect fundamental differences in key N transformation pathways operative in these systems.

Within this model framework, the δ15N of NO2− provides an additional diagnostic to estimate the relative contribution of nitrification (and/or anammox) to the NO3− pool. In particular, very deplete δ15NNO2 values relative to the NO3− pool may be characteristic of elevated NXR/NAR flux ratios: a dynamic that appears corroborated by analogously low δ15NNO2 values in marine denitrifying zones, albeit lower than those predicted by our model simulations.

Some uncertainties also remain that require resolution to ensure accuracy of interpretations. For one, O isotope effects associated with NO3− production by anammox remain undocumented; whereas dynamics may be similar to those for NO2− oxidizing bacteria, this should be confirmed. Second, the nature and environmental extent of the purported “enzyme-catalyzed equilibrium N isotope effect” between NO3− and NO2− during anammox should also be further explored. Diagnostic estimates of NXR/NAR flux ratios are sensitive to the broad potential range of N isotope effects during NO2− oxidation to NO3−. Third, the apparent discrepancy between model and measured δ15NNO2 in marine systems merits examination to assess the involvement of NO2− in potential abiotic/inorganic reactions. Finally, the premise that NO2− oxygen isotopes in marine and freshwater denitrifying systems are fully equilibrated with water should be further interrogated, as even partial O isotope disequilibrium could influence diagnostics of N fluxes and associated isotope effects (S3. Simulation Without Isotope Equilibration of NO2− with Water). Continued inquiry into isotope systematics of N cycling will lead to an increasingly robust framework from which to examine N cycle dynamics across ecosystems.

6. Materials and Methods

Given the number of variables involved in calculating the model solutions, we made a number of decisions for model parameterizations to maintain clarity. First, we chose a range of isotope effects based on published studies using pure cultures of representative organisms and/or purified enzymes when possible (Table 1). As studies of organism-level isotope effects have demonstrated broad variability, whether by bacterial strain or growth conditions, for brevity and simplicity, we also established “standard” model conditions having generally midrange values for isotope effects (Table 1). Second, a study published this year demonstrates that the N and O isotope effects for NIR are coupled differently depending on the type NO2− reductase involved (59). Our simulations, however, are based on parameterization of 15εnir and 18εnir coupled in a ratio of 1:1, assumed before this insight. Regardless, this inaccuracy does not ultimately impact the conclusions reached herein (Section 3.3 and S3.2. Influence of 18εnar and 18εnir). Third, the N and O isotope effects for NXR in the model parameterization remain uncoupled because studies of NO2−-oxidizing organisms have evidenced no connection in their magnitudes (5). Finally, we allow the initial N and O isotopic composition of NO3− to vary across a representative range (−10‰ to +15‰ for both δ15N and δ18O) while using values of +5‰ for both as standard conditions.

To date, no information exists on O isotope systematics of anammox, such that we assume O isotope effects similar to that of NO2− oxidizing bacteria, as enzymatic pathways are analogous (66). However, the organism-level inverse N isotope effect reported for anammox cultures for NO3− production driven by NXR exhibits higher values (−35‰) (43) than those observed in cultures of bacterial NO2− oxidizing bacteria (−13‰) (4) and may also include a very large enzymatically driven isotope equilibrium between NO3− and NO2− of −61‰ (43).

S1. Postulates to Explain Deviations from 1 in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N Trajectories in Freshwater

The discrepancy between field observations and culture estimates of could stem from a methodological artifact and the lack of established δ18ONO3 reference materials (67). Early δ18ONO3 measurements were made by off-line sealed-tube pyrolysis, which may suffer from exchange of O-atoms with the glass and/or contamination by O-bearing contaminants (68). Such δ18O scale contraction is now corrected by use of calibrated NO3− reference materials (67). Importantly, the establishment of international NO3− isotopic reference materials has not eliminated the persistence of ∆δ18O:∆δ15N ∼0.6 found in freshwater systems (69). The activity of an auxiliary Nap NO3− reductase has been evoked to explain ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trends in freshwater environments (70), on the basis that NO3− reduction mediated by Nap has been shown to exhibit lower ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (9, 23, 70). However, evidence for this nonrespiratory pathway as a major environmental sink for NO3− is lacking and largely inconsistent with the enzymatic basis of heterotrophic respiratory NO3− consumption, which specifically implicates the Nar NO3− reductase. Plasticity in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories for Nar-mediated denitrification could also explain the apparent discrepancy between cultures and the environment and was reported among denitrifying cultures in one study (71). The δ18ONO3 trends therein, however, were indirectly inferred from NO2− δ18O and may have been affected by NO2−-water oxygen isotopic exchange (29, 30). Given lower δ18OH2O values in freshwater systems relative to seawater, oxygen isotopic equilibration between NO3− and water could hypothetically lead to lower δ18ONO3 values in freshwater systems and to a consequent decrease in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories. The timescale of this abiotic exchange process (>109 y), however, precludes its overall relevance for modern biosphere processes (72). Nevertheless, the potential ingrowth of water oxygen atoms into NO3− could result from reverse activity of the Nar enzyme. Such enzymatic reversibility has been demonstrated to influence the evolving δ18O of sulfate during sulfate reduction (73). Although a similar dynamic has been suggested for NO3− (73), there is no evidence for enzymatic reversibility of Nar in the literature. Importantly, denitrifier cultures amended with incremental concentrations of 18O-enriched water showed no differences in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories among treatments, indicating that Nar activity is not reversed in vivo (12). In addition, the biological production of NO3− occurring in tandem with denitrification has been postulated to account for the apparent differences in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories between cultures and freshwater environments (39). Wunderlich et al. (40) showed that some NO2−-oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Nitrobacter vulgaris) under suboxic conditions use NO2− oxidoreductase (Nxr) reversibly to reduce NO3−, modifying apparent ∆δ18ONO3:∆δ15NNO3 trajectories during denitrification. Although intriguing, the environmental ubiquity of this specific process is difficult to assess. Nevertheless, this scenario raises a key premise that the biological oxidation of NO2− invariably results in the incorporation of water-derived O atoms into the NO3− pool.

S2. Equations Used in Time-Dependent NO3− Isotope 1 Box Model

S3. Simulation Without Isotope Equilibration of NO2− with Water

S3.1. Influence of δ18OH2O.

Model simulations in which NO2− does not equilibrate with water yield ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories that are predominantly above 1 (Fig. S1). The relative amplitudes of positive deviations correlate with the amplitude of the NXR/NAR flux ratio, with theoretical ∆δ18O:∆δ15N values upward of 7.0 at NXR/NAR ratios of 0.9. The δ18OH2O in these parameterizations accounts for only modest differences among ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories for any given NXR/NAR ratio, unlike corresponding parameterizations with completely equilibrated NO2−, due to a lack of NO2−–water equilibration. The reduced influence of the δ18OH2O on ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories arises because only a single O atom is incorporated during oxidation of NO2− to NO3− (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). The δ18O of nitrified NO3− is otherwise determined largely by the δ18O of the NO2− pool, which is comparatively elevated due to the branching O isotope effect associated with NO3− reduction, 18εnarBR, producing NO2− having a δ18O 25‰ greater than the NO3− δ18O concurrently abstracted (19, 33). Consequently, the δ18O of nitrified NO3− in simulations without O isotope exchange is considerably more elevated than the δ18ONO3 removed concurrently by denitrification, resulting in net increases in δ18O relative to δ15N and, therefore, positive deviations in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories from a nominal value of 1.

In parameterizations without oxygen isotope equilibration of NO2−, curvature in the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory is also apparent (Fig. 2) because the δ18O of nitrified NO3− does not increase in step with the δ18O increase of the NO3− pool, whereas the δ15N of nitrified NO3− still increases in constant proportion to the δ15N increase of the NO3− pool (Fig. S2). In this case, however, two of the oxygen atoms in nitrified NO3− deriving from NO2− do increase in proportion to the δ18O of the NO3− pool, whereas the δ18O of the single oxygen atom deriving from water remains constant. Curvature of the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory thus arises because of a lower degree of increase of the δ18O of nitrified NO3− relative to the corresponding rate of increase of the δ18O of the NO3− pool. Accounting for more representative 18εnir to 15εnir ratios (65) than those prescribed here would result in differences in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N amplitude and curvature, but would nevertheless yield largely analogous patterns.

S3.2. Influence of 18εnar and 18εnir.

In the case of no oxygen isotope equilibration of NO2− with water, the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory is, in fact, sensitive to variations in amplitude of 18εnar, in conjunction with that of the enzymatic branching isotope effect of NO3− reductase, 18εnarBR, leading to ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1 (Fig. S4B). The δ18O removed from the NO3− pool is a function of 18εnar, whereas the NO2− produced concurrently has a δ18ONO2 that is ∼25‰ greater than the δ18O abstracted from the NO3− pool, due to the branching isotope effect (19, 29). The δ18O of NO3− produced by subsequent NO2− oxidation is thus consistently elevated compared with that removed by denitrification, consistently leading to ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories above 1 (Fig. S1).

Without full equilibration, 18εnir has leverage on the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory that is counter to that of the corresponding 15εnir, but quantitatively less important than that of 15εnir because the 18O-enrichment of NO2− due to 18εnir is effectively diluted by the subsequent incorporation of an additional oxygen atom from water into NO3− during NO2− oxidation (Fig. 1 and Fig. S4D). More representative parameterizations of 18εnir relative to 15εnir would yield quantitatively different yet qualitatively analogous ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories.

S3.3. Influence of Initial δ18ONO3.

In simulations without oxygen isotope equilibration, the difference between δ18ONO3 and δ18OH2O has a comparatively diminished influence on the ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory, because the δ18O of nitrified NO3− is no longer influenced by oxygen isotope equilibration with water, but only sensitive to oxygen atom incorporation from water during NO2− oxidation (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). We note that the δ18O of nitrified NO3− is also rendered sensitive to oxygen atom incorporation from water during ammonium oxidation to NO2−; however, an AMO flux is not prescribed under our standard model conditions (Table 1 and S4. Impact of NO3− Production by AMO). The δ18ONO3 produced by nitrification when NO2− is not equilibrated is then comparatively 18O-enriched due to the branching isotope effect of NO3− reduction, 18εnarBR, resulting in positive deviations in ∆δ18O:∆δ15N from a nominal trajectory of 1 (Figs. S1 and S2).

In simulations without isotopic equilibration of NO2−, in which nearly all ∆δ18O:∆δ15N solutions are above 1, the amplitude of the positive offset from 1 is proportional to the NXR/NAR ratio for a given δ18OH2O (Fig. S1), reflecting the relative amount of 18O-enriched NO3− returned to the NO3− pool by NO2− oxidation.

S4. Impact of NO3− Production by AMO

The presence of AMO in the model architecture, parameterized as the ratio of AMO/NAR, constitutes a net input of N to the system whose magnitude is not constrained numerically by that of other fluxes (S2. Equations Used in Time-Dependent NO3− Isotope 1 Box Model). AMO thus contributes directly to the NO2− pool (Fig. 1), where it is subject to reduction (NIR) and/or oxidation (NXR). The AMO flux is then compensated by increases NIR and/or NXR. We consider here only conditions resulting in the net removal of NO3−, where the increased contribution of AMO is not allowed to result in the net production of NO3− (NAR ≥ NXR). Regardless, most model solutions at relatively elevated NXR/NAR ratios (NXR/NAR ≥ 0.5 and standard conditions) produce nonviable solutions in which apparent 15εdnf values exceed the empirical limit of 30‰ (Figs. S1 and S3A). The prescription of any AMO flux exacerbates this dynamic, increasing the NO2− δ15N, consequently producing relatively 15N-enriched NO3− that amplifies 15εdnf. Thus, where NXR/NAR ratios are ≥0.5, viable solutions persist only at very low prescriptions of AMO/NAR (≤0.05; Fig. S6). This general dynamic extends to the entire parameterized range of δ15NNH4 values (−20‰ to 15‰; Table 1), which result in the production of 15N-enriched NO2− by AMO and a consequent increase in the δ15NNO3 produced by NXR, under nearly all combinations of boundary conditions. Among the few viable solutions that remain at elevated NXR/NAR ratios, slight increases in the AMO/NAR ratio result in a marked reduction in the corresponding ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectory (Fig. S6B), due to an increase in 15εdnf that is not matched by a corresponding increase in 18εdnf. Together, the tendency for increasing AMO to lower ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories while increasing the likelihood of generating invalid 15εdnf solutions appears to exclude any substantial flux of AMO in marine denitrifying systems. Trajectories therein reach upward of 1.3, values that are produced exclusively at elevated NXR/NAR ratios and thus minimal AMO (34, 35).

At lower NXR/NAR flux ratios, increasing the AMO flux leads to comparatively modest increases in 15εdnf and correspondingly modest reductions of ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trajectories (Fig. S6). The limited sensitivity of NO3− isotopes to any NO2− production from AMO thus renders the potential importance this flux difficult to detect from NO3− isotopes distributions alone. Nevertheless, we consider that any NO3− production in anaerobic aquifers (where NXR/NAR flux ratios may be relatively low; Section 3.5.2) is likely associated with anammox rather than aerobic nitrification, potentially discounting the involvement of ammonium δ15N in modulating NO3− ∆δ18O:∆δ15N trends altogether (Section 3.5.2). If correct, this inference would facilitate a more quantitative interpretation of relative N cycle fluxes in soils and aquifers from natural abundance NO3− (and NO2−) isotope distributions, a topic addressed in Section 3.5.2.

S5. Model Inversion

Adapting the model architecture outlined above, we use an inverse approach to numerically optimize values of 15εnar, 15εnir, 15εnxr, and NXR/NAR. As the model system of equations is underdetermined, we use a genetic solving algorithm method in Solver (mutation rate = 0.75, convergence = 0.0000001, population size = 100; Frontline Systems; Microsoft Excel) and a least-squares criterion to iteratively find the best fit to the published values for NO3− concentrations (estimating the fraction of consumption or fNO3) along with δ15NNO3 and δ18ONO3. Uncertainty in parameter estimates (1 SD) is expressed as the SE of successive model-runs (n > 25).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript benefited from comments by two anonymous reviewers. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants EAR-1252089 (to J.G.) and EAR-1252161 (to S.D.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1601383113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gruber N, Galloway JN. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature. 2008;451(7176):293–296. doi: 10.1038/nature06592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendall C, Elliott EM, Wankel SD. Tracing Anthropogenic Inputs of Nitrogen to Ecosystems. Wiley-Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2007. pp. 375–449. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariotti A, et al. Experimental determination of nitrogen kinetic isotope fractionation: Some principles; illustration for the denitrification and nitrification processes. Plant Soil. 1981;62(3):413–430. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casciotti KL. Inverse kinetic isotope fractionation during bacterial nitrite oxidation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2009;73(7):2061–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchwald C, Casciotti KL. Oxygen isotopic fractionation and exchange during bacterial nitrite oxidation. Limnol Oceanogr. 2010;55(3):1064–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casciotti KL, McIlvin M, Buchwald C. Oxygen isotopic exchange and fractionation during bacterial ammonia oxidation. Limnol Oceanogr. 2010;55(2):753–762. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchwald C, Santoro AE, McIlvin MR, Casciotti KL. Oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate and nitrite produced by nitrifying cocultures and natural marine assemblages. Limnol Oceanogr. 2012;57(5):1361–1375. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granger J, Sigman DM, Needoba JA, Harrison PJ. Coupled nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation of nitrate during assimilation by cultures of marine phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr. 2004;49(5):1763–1773. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granger J, Sigman DM, Lehmann MF, Tortell PD. Nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation during dissimilatory nitrate reduction by denitrifying bacteria. Limnol Oceanogr. 2008;53(6):2533–2545. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kritee K, et al. Reduced isotope fractionation by denitrification under conditions relevant to the ocean. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2012;92:243–259. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karsh KL, Granger J, Kritee K, Sigman DM. Eukaryotic assimilatory nitrate reductase fractionates N and O isotopes with a ratio near unity. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(11):5727–5735. doi: 10.1021/es204593q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wunderlich A, Meckenstock R, Einsiedl F. Effect of different carbon substrates on nitrate stable isotope fractionation during microbial denitrification. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(9):4861–4868. doi: 10.1021/es204075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snider DM, Spoelstra J, Schiff SL, Venkiteswaran JJ. Stable oxygen isotope ratios of nitrate produced from nitrification: (18)O-labeled water incubations of agricultural and temperate forest soils. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(14):5358–5364. doi: 10.1021/es1002567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kool DM, Wrage N, Oenema O, Van Kessel C, Van Groenigen JW. Oxygen exchange with water alters the oxygen isotopic signature of nitrate in soil ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43(6):1180–1185. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Böttcher J, Strebel O, Voerkelius S, Schmidt HL. Using isotope fractionation of nitrate nitrogen and nitrate oxygen for evaluation of microbial denitrification in a sandy aquifer. J Hydrol (Amst) 1990;114(3-4):413–424. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aravena R, Robertson WD. Use of multiple isotope tracers to evaluate denitrification in ground water: Study of nitrate from a large-flux septic system plume. Ground Water. 1998;36(6):975–982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amberger A, Schmidt H-L. Natürliche isotopengehalte von nitrat als Indikatoren für dessen herkunft. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1987;51(10):2699–2705. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigman DM, et al. A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater. Anal Chem. 2001;73(17):4145–4153. doi: 10.1021/ac010088e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casciotti KL, Sigman DM, Hastings MG, Böhlke JK, Hilkert A. Measurement of the oxygen isotopic composition of nitrate in seawater and freshwater using the denitrifier method. Anal Chem. 2002;74(19):4905–4912. doi: 10.1021/ac020113w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigman DM, Lehman SJ, Oppo DW. Evaluating mechanisms of nutrient depletion and C-13 enrichment in the intermediate-depth Atlantic during the last ice age. Paleoceanography. 2003;18(3):1072–1089. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shearer G, Schneider JD, Kohl DH. Separating the efflux and influx components of net nitrate uptake by Synechococcus-R2 under steady-state conditions. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137(5):1179–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Needoba J. Nitrogen Isotope Fractionation by Four Groups of Marine Algae During Growth on Nitrate. Univ of British Columbia; Vancouver: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treibergs LA, Granger J. Enzyme level N and O isototope effects of assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reduction. Limnol Oceanogr. 2016 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jetten MSM, et al. Biochemistry and molecular biology of anammox bacteria. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44(2-3):65–84. doi: 10.1080/10409230902722783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer B, Bollwerk SM, Mansfeldt T, Hütter B, Veizer J. The oxygen isotope composition of nitrate generated by nitrification in acid forest floors. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2001;65(16):2743–2756. [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiSpirito AA, Hooper AB. Oxygen exchange between nitrate molecules during nitrite oxidation by Nitrobacter. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(23):10534–10537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollocher TC. Source of the oxygen atoms of nitrate in the oxidation of nitrite by Nitrobacter agilis and evidence against a P-O-N anhydride mechanism in oxidative phosphorylation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;233(2):721–727. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Nicholas DJD, Williams EH. Definitive 15N NMR evidence that water serves as a source of ‘O’ during nitrite oxidation by Nitrobacter agilis. FEBS Lett. 1983;152(1):71–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casciotti KL, Böhlke JK, McIlvin MR, Mroczkowski SJ, Hannon JE. Oxygen isotopes in nitrite: Analysis, calibration, and equilibration. Anal Chem. 2007;79(6):2427–2436. doi: 10.1021/ac061598h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]