Significance

The development of more effective arterial embolization therapy is one of the major challenges of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We showed that the addition of tirapazamine, a cytotoxic agent that can be activated by sublethal hypoxia, greatly improved the efficacy of arterial embolization in killing HCC developed in hepatitis B virus X protein transgenic mice. Nearly complete tumor necrosis was identified in most HCCs shortly after combination treatment. This preclinical study showed that the combination of tirapazamine and arterial embolization is a regimen that improved the liver tumor-killing activity, but spared the normal hepatocytes. These results form the basis for the ongoing clinical phase I trial to determine whether this treatment can be an effective therapy for intermediate stage HCC.

Keywords: hypoxia, hepatocellular carcinoma, orthotopic, transarterial embolization

Abstract

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the main treatment for intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification because of its exclusive arterial blood supply. Although TACE achieves substantial necrosis of the tumor, complete tumor necrosis is uncommon, and the residual tumor generally rapidly recurs. We combined tirapazamine (TPZ), a hypoxia-activated cytotoxic agent, with hepatic artery ligation (HAL), which recapitulates transarterial embolization in mouse models, to enhance the efficacy of TACE. The effectiveness of this combination treatment was examined in HCC that spontaneously developed in hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) transgenic mice. We proved that the tumor blood flow in this model was exclusively supplied by the hepatic artery, in contrast to conventional orthotopic HCC xenografts that receive both arterial and venous blood supplies. At levels below the threshold oxygen levels created by HAL, TPZ was activated and killed the hypoxic cells, but spared the normoxic cells. This combination treatment clearly limited the toxicity of TPZ to HCC, which caused the rapid and near-complete necrosis of HCC. In conclusion, the combination of TPZ and HAL showed a synergistic tumor killing activity that was specific for HCC in HBx transgenic mice. This preclinical study forms the basis for the ongoing clinical program for the TPZ-TACE regimen in HCC treatment.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the sixth most common solid malignancy, accounts for approximately three-quarters of a million deaths worldwide every year (1). Over the past two decades, the incidence of HCC has remained high in Asia and has steadily increased in the United States and Europe (1). Treatment for HCC largely depends on the stage of the disease. Diagnosis is usually delayed, as ∼30–40% of the patients are already in the intermediate stage at their initial visit, and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the most commonly used treatment for these patients (2). However, TACE achieves only a 20–30% tumor remission rate, and recurrence is common, resulting in a 3-y survival rate of only ∼30% (3). This poor survival rate needs to be improved.

The mechanism by which arterial embolization preferentially kills HCC but spares adjacent liver tissues arises from the unique dual blood supply to the liver. Normal liver receives 75% of its blood supply from the portal vein (PV) and the remaining 25% from the hepatic artery (HA) (4). In contrast, HCC almost exclusively receives its blood supply from the HA (5). Based on this unique pattern, embolization has been used to selectively block the arterial blood supply to HCC, causing transient but profound ischemia and depriving HCC cells from essential oxygen and nutrients, thus killing the tumors.

However, because of the heterogeneity of the tumor vessels within HCC, the embolization of the tumor-feeding arteries usually results in different degrees of ischemia and hypoxia, ranging from 0.1 to 10 μM oxygen in HCC after embolization (6). Only the cancer tissues subjected to lethal hypoxia (less than 1 μM) will eventually die; other cancer tissues that are exposed to sublethal hypoxia (greater than 1 μM) usually survive and regrow. Therefore, this result indicates that a considerable proportion of HCC can survive transient ischemic injuries after embolization, mainly because they are only exposed to sublethal hypoxia.

Strategies have been proposed to combine arterial embolization with radiofrequency ablation, radiotherapy, chemotherapeutic, or biological agents to improve the tumor killing efficacy (7). Drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (DEB-TACE) and radioembolization have also been used, but have many unresolved issues (8). Therefore, the development of a more effective TACE combination therapy for patients with intermediate stage HCC is justified.

Therefore, we propose to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of arterial embolization by combining it with hypoxia-activated cytotoxic agents. The effects of arterial embolization can be amplified if these agents are activated by sublethal hypoxia, and the surviving cancer cells can then be killed. Consequently, tirapazamine (TPZ), a hypoxia-activated cytotoxic agent, was investigated. TPZ is a bioreductive agent that can be activated at hypoxia levels similar to the sublethal zones in arterial embolization-treated HCC. Through a one-electron reduction process by cellular reductases, free radicals are produced that cause single- or double-stranded DNA breaks and kill the cells (9, 10). Under normoxic conditions, reduced TPZ is rapidly oxidized to an inactive prodrug and causes no harmful effects.

TPZ has been tested in lung, cervical, and head/neck cancers in combination with chemotherapy or chemoradiation (11–13). Although a phase II trial showed clinical advantages (14), a phase III trial failed to show additional benefits of adding TPZ (15). This failure is mainly due to inadequate hypoxia within the tumors. With the exception of the liver, cancers in most organs receive oxygenated blood from the same arteries that supply the adjacent normal tissues, thus it is extremely difficult to interrupt only the arterial blood supply to the tumors and spare the normal tissues. Therefore, HCC becomes an ideal target because it receives most of its blood supply from the HA, and the nontumor liver tissues mainly receive their blood supplies from the PV. Arterial embolization can effectively choke the arterial blood supply to HCC, which creates sufficient hypoxia to activate TPZ and kill HCC. However, it does not cause hypoxia in the nontumor tissues and, thus, TPZ cannot be activated to kill the normal hepatocytes. In this study, we conducted a proof-of-concept experiment to test this hypothesis in hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx)-transgenic mice, a spontaneous HCC mouse model, and our results confirmed this hypothesis.

Results

HCC That Spontaneously Developed in HBx Transgenic Mice, but Not the Orthotopic HCC Xenografts, Receives Its Tumor Blood Flow Exclusively from the Hepatic Artery.

We initially used a conventional orthotopic xenograft model by inoculating the left lobe of the liver in nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficient (NOD-SCID) mice with human Huh-7 hepatoma cells to identify a suitable animal model to test the efficacy of the combination of TPZ and arterial embolization. After tumor establishment, hepatic artery ligation (HAL) was used as an alternative procedure for arterial embolization because it is extremely difficult to perform arterial embolization in small animals because of the small caliber of the blood vessels. We performed a left HAL, which was followed by a PV ligation (PVL), and measured the changes in pO2 and blood flow in the tumor by using the combined OxyLite/OxyFlo probes (protocol outlined in Fig. S1A). A significant decrease in both parameters was observed after HAL plus PVL, but not HAL alone (Fig. S1 B and C). This result indicated that the blood flow of HCC in the orthotopic xenograft model was supplied by both the HA and PV and, thus, it was not an appropriate model to reflect human HCC or for subsequent experiments.

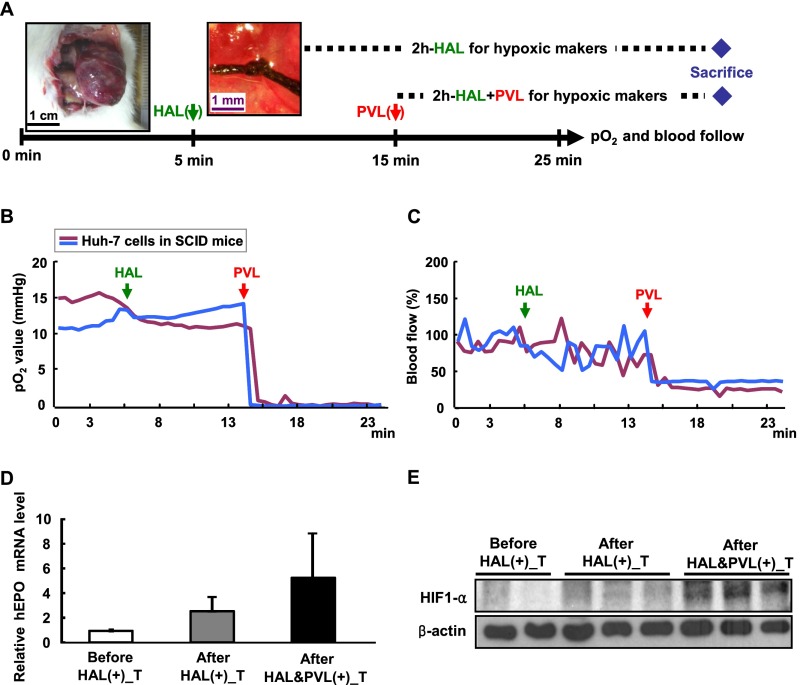

Fig. S1.

Orthotopic xenograft mouse HCC model is supplied by both the HA and PV. (A) Schematic illustration of the pO2 and blood flow measurement process by HAL and PVL in the left liver lobe. The black arrow indicates the combined OxyLite/OxyFlo probes inserted into the hepatic tumor to monitor the pO2 and blood flow continuously. The green arrow indicates the time of HAL, and red arrow indicates the time of PVL. The blue diamond indicates the sacrifice point. (B and C) Hypoxia cannot be established in the hepatic tumor of the orthotopic xenograft mouse model when only HAL was used. The probes were inserted into the hepatic tumor to monitor the pO2 (B) and blood flow (C) continuously. (D and E) Hypoxic markers of EPO and HIF1-α cannot be induced in the hepatic tumor of the orthotopic xenograft mouse model when only HAL was used for 2 h. Tumor tissues were harvested before, after the 2-h HAL, and after the 2-h combined HAL and PVL treatments from the left liver lobe. All samples were evaluated for the EPO mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR (D) and HIF-1α protein levels (E) by Western blotting, with the tumor of left liver lobe before L-HAL as control.

We next tried to examine the blood supply in HCC from the hepatic-specific HBx transgenic mice, which spontaneously developed HCC at the age of ∼18 mo (16). We selectively performed a transient HAL in the left HA in wild-type mice, precancerous HBx transgenic mice, and HCC-bearing HBx transgenic mice (protocol outlined in Fig. 1A). The tumors in the left liver lobe served as the target lesions, whereas those in the right lobe served as the control without HAL. Only the pO2 from the tumor of left liver lobe was decreased after HAL, which was associated with a reduction in the tumor blood flow to <25% of the baseline, whereas the pO2 in the left lobe of the normal or precancerous livers was not affected (Fig. 1 B and C).

Fig. 1.

HCC in HBx transgenic mice is mainly supplied by the HA. (A) Schematic diagram of the protocol used to measure the changes in pO2, blood flow, and the expression of hypoxic markers following transient HAL of the left lobe of liver. The black arrow indicates the continuous monitoring of pO2 and blood flow with combined OxyLite/OxyFlo probes inserted into the liver. The green and red arrows indicate the time for HAL and HAL release, respectively. The blue diamond indicates the sacrifice point. (B and C) Hypoxia can be created in the HCC of the HBx transgenic mice by HAL. The probes were inserted into different parts of the liver in mice at different ages, including the left liver lobe of wild-type mice and precancerous HBx transgenic mice, as well as the HCC of HBx transgenic mice, to continuously monitor the pO2 (B) and blood flow (C) during the transient HAL treatment period. (D and E) The expression of hypoxic markers, such as EPO and HIF-1α, can be induced in the HCC of HBx transgenic mice following HAL for 2 h. Tissues from different parts of the left lobe of the liver were collected before and 2 h after L-HAL. The tumor and nontumor parts of the right lobe of the liver were also collected for comparison. The EPO mRNA levels (D) and HIF-1α protein levels (E) in all samples were evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. The nontumor tissue of left liver lobe before L-HAL was used as a control.

The HAL-induced hypoxia in HCC was further validated by examining the expression of two hypoxic markers, erythropoietin (EPO) (mRNA level) and HIF-1α (protein level) (17). The expression of both markers was elevated in the HCC in the left lobe 2 h after HAL, whereas those in the adjacent nontumorous liver and in the HCC in the right lobe did not change significantly (Fig. 1 D and E). The specific induction of hypoxia in HCC by HAL has been further validated by IHC staining after pimonidazole treatment, which can be activated by hypoxia and forms adducts with cellular proteins for IHC detection (18). The HCC in the liver lobe targeted by HAL showed a stronger signal than that in the nontumorous tissues (Fig. S2).

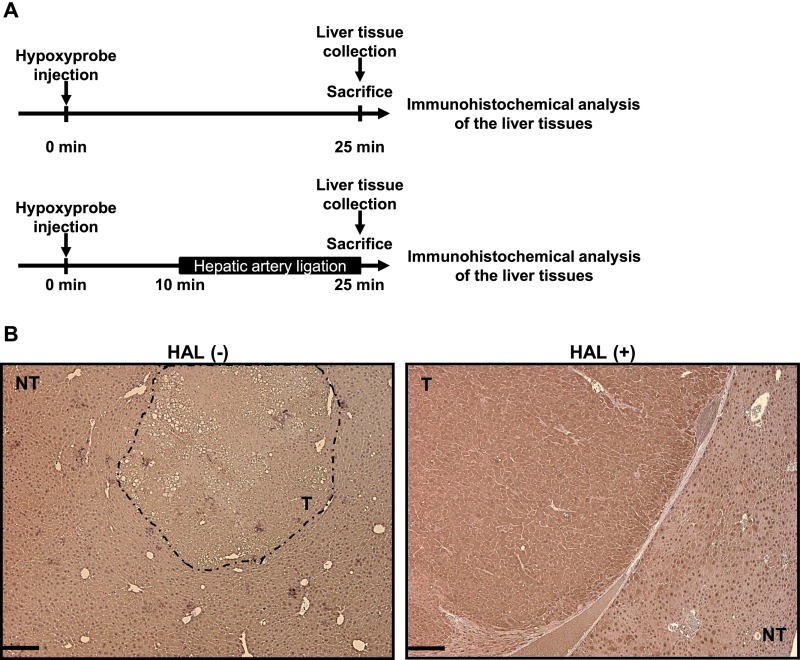

Fig. S2.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of Hypoxyprobe chemical adducts in HCC-bearing HBx transgenic mice with or without L-HAL. (A) Schematic diagram of the protocol for Hypoxyprobe injection and liver tissue analysis. (B) The representative results for the IHC staining of the nontumor and the tumor liver tissues in the left liver lobe from the control mice [HAL(-)] and the mice with L-HAL [HAL(+)]. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

In summary, transient HAL interrupted the tumor blood flow and induced hypoxia in only the HCC located in the region perfused by the target artery, but did not affect the blood flow and oxygen in the nontumorous liver tissues. This finding supports that the blood supply of HCC in the HBx transgenic mice resembles that of HCC in humans, which is thus suitable for evaluating the efficacy of the combination of TPZ and HAL.

Dose Escalation Study of Tirapazamine in Wild-Type and Precancerous Liver in Combination with the Transient Hepatic Artery Ligation.

We administered saline or 3, 6, or 20 mg/kg TPZ by i.v. infusion through the tail veins of the wild-type mice in a dose escalation study to determine the dosages of TPZ that should be combined with transient HAL. The toxicities of TPZ with transient left HAL (L-HAL) were evaluated. The pO2 and blood flow in the left liver lobe of wild-type mice showed no significant changes after HAL (Fig. 2A), indicating that the normal liver was not under hypoxia following the treatment. All mice in the treatment groups survived for 7 d and did not show significant changes in body weights or the total serum bilirubin levels (Fig. 2 B and C). However, the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels increased at day 1 after treatment in the groups that received higher doses of TPZ, particularly for the groups that were treated with 20 mg/kg TPZ (Fig. 2D).

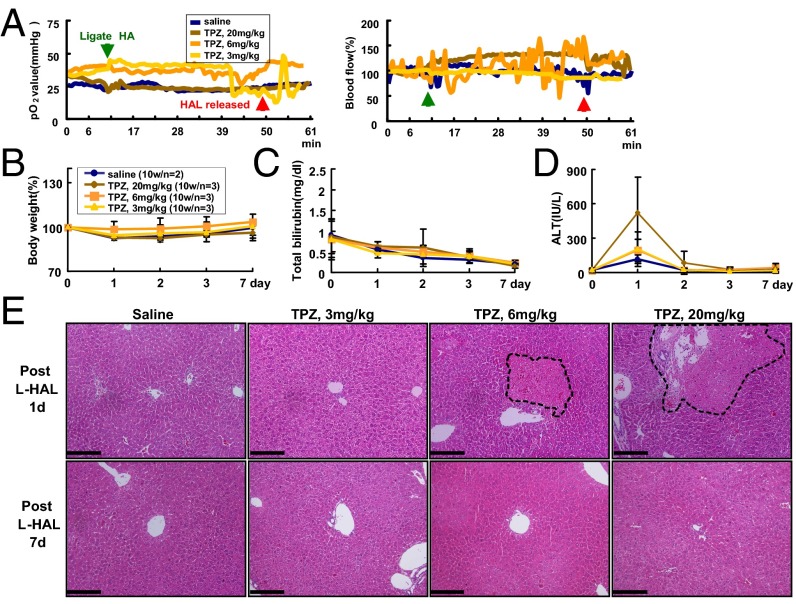

Fig. 2.

Dose escalation study of TPZ combined with transient L-HAL in C57BL/6 mice. The mice were treated with 0.9% saline or three doses of TPZ, 3, 6, and 20 mg/kg, through tail vein injections before transient L-HAL. (A) Transient L-HAL could not induce hypoxia in the left lobe of wild-type mouse liver. The green arrow indicates the time when L-HAL was initiated, and the red arrow indicates the time when L-HAL was released. All groups exhibited similar changes in body weights (B) and total bilirubin levels (C). (D) An elevation of the ALT levels was observed on day 1 in mice that were treated with 20 mg/kg TPZ. (E) Histopathological examination of the mouse livers. The liver tissues were collected from transient L-HAL–treated liver lobes from each group after 1 d (Upper) or 7 d (Lower) of treatment and were processed for H&E staining. The data are representative of each independent group. The black dashed circle indicates the necrotic region. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

The liver tissues were collected from the left lobe of the nontumorous liver from each group on day 1 and day 7 after treatment and processed for the H&E staining; representative results are shown in Fig. 2E (Upper, day 1; Lower, day 7 after treatment). Very mild necrosis (nearly 1%) was detected in the liver tissues of only the mice that received a 1-d treatment with 6 and 20 mg/kg TPZ (Fig. 2E, Upper), but not in the saline and 3 mg/kg TPZ-treated mice. However, no pathological changes were detected in the livers of any of the four groups of mice on day 7 after treatment (Fig. 2E, Lower), suggesting that the transient hepatocyte injury recovered by day 7 after the TPZ-HAL treatment.

After the safe dosage of TPZ was determined in wild-type mice, we further evaluated its tolerability in the precancerous livers from 13- to 14-mo-old HBx transgenic mice, which already showed abnormal histological changes, as reported (19). The mice were treated with saline or 3 and 6 mg/kg TPZ in combination with the transient L-HAL and were followed for up to 7 d. None of the treatments caused significant changes in body weight or the serum bilirubin and ALT levels, and none of the animals had died at the end of the follow-up (Fig. S3 A–D). The histopathological features of the liver were also similar to those in the control mice without combination therapy (Fig. S3E). Finally, the safe dose of TPZ was tested in the mouse model of liver cirrhosis induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). Neither the 3 nor 20 mg/kg doses of TPZ in combination with the transient L-HAL caused death or significant changes in body weight or total serum bilirubin and ALT levels; necrosis of the cirrhotic liver was not detected at the end of the 7-d follow-up (Fig. S4).

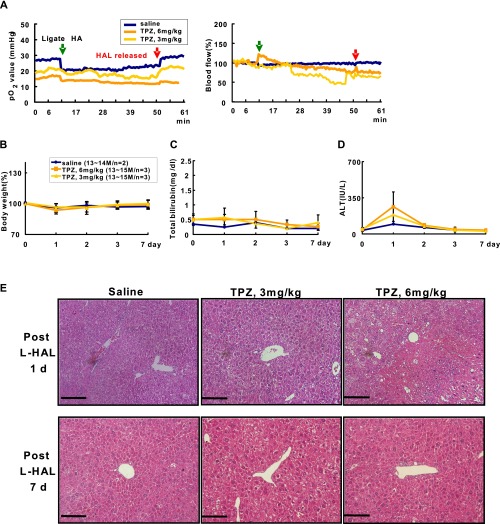

Fig. S3.

Dose escalation study of TPZ combined with transient L-HAL in precancerous liver of the HBx transgenic mice. Mice were treated with 0.9% saline and two doses of TPZ, 3 and 6 mg/kg, through tail vein injection before transient L-HAL. (A) Transient L-HAL cannot induce hypoxia in the left liver lobe of precancerous HBx transgenic mice. The green arrows indicate the time of L-HAL, and the red arrows indicate the time of L-HAL release. Body weight changes (B), total bilirubin changes (C), and ALT level changes (D) during follow up. (E) Representative H&E staining results of livers from each group of mice harvested at day 1 (Upper) and day 7 (Lower) after treatment. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

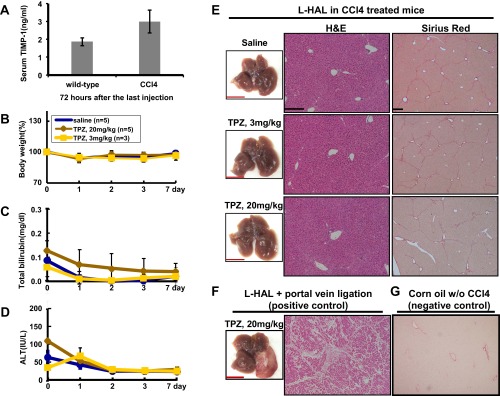

Fig. S4.

Determine the safe dose for TPZ, in combination with transient L-HAL, in the mouse model with cirrhotic livers induced by CCl4. (A) The cirrhotic livers in C57/B6 male mice induced by repeated CCl4 injection were confirmed by the elevation of serum TIMP-1. The mice were then treated with saline (control) or with 3 and 20 mg/kg TPZ through tail vein injection, in combination with transient L-HAL. The body weights (B), total bilirubin (C), and ALT levels (D) in serum of these mice were determined. (E) The liver tissues collected at the end of 7 d follow were collected from the three groups of mice for the H&E (Left) and Sirius Red staining (Right). (F) The left liver lobe treated with 20 mg/kg of TPZ in combination with L-HAL and L-PVL was served as the positive control for H&E staining with severe necrosis. (G) The male mice treated with corn oil (without CCl4) were served as negative control for the Sirius Red staining. Data are representative of each independent group. (Scale bars: black, 0.2 mm; red, 1 cm.)

Based on these results, we decided to use 3 mg/kg dose of TPZ for the further evaluations of the efficacy of the combination therapy, which was well tolerated in combination with L-HAL.

Superior Tumor Killing Effect of Tirapazamine Compared with Doxorubicin for HCC in Combination with the Transient Hepatic Artery Ligation.

Doxorubicin, a chemotherapeutic drug that is commonly used with TACE for the treatment of HCC, was used as a control to compare the antitumor effects with TPZ. The HBx transgenic mice containing palpable HCC were injected with saline, doxorubicin (10 mg/kg), or TPZ (3 mg/kg) through the tail veins, followed by transient L-HAL. The mice were examined at day 1 and day 7 after treatment to evaluate the effects on tumor necrosis.

We first analyzed the serum samples and liver tissues collected from each group of mice on day 1 after treatment. The ALT levels were transiently elevated in the TPZ-HAL–treated mice (Fig. S5 A and B). The HCC and nontumorous liver tissues collected from the transient-HAL–treated left liver lobe of each group of mice were processed for H&E staining. The control mice that were treated with 0.9% saline did not show detectable necrosis. In contrast, the TPZ-HAL–treated mice showed >99% necrosis in the HCC region and only ∼5% necrosis in the nontumorous region; however, only ∼5% necrosis was observed in the doxorubicin-HAL–treated HCC region (Fig. S5C).

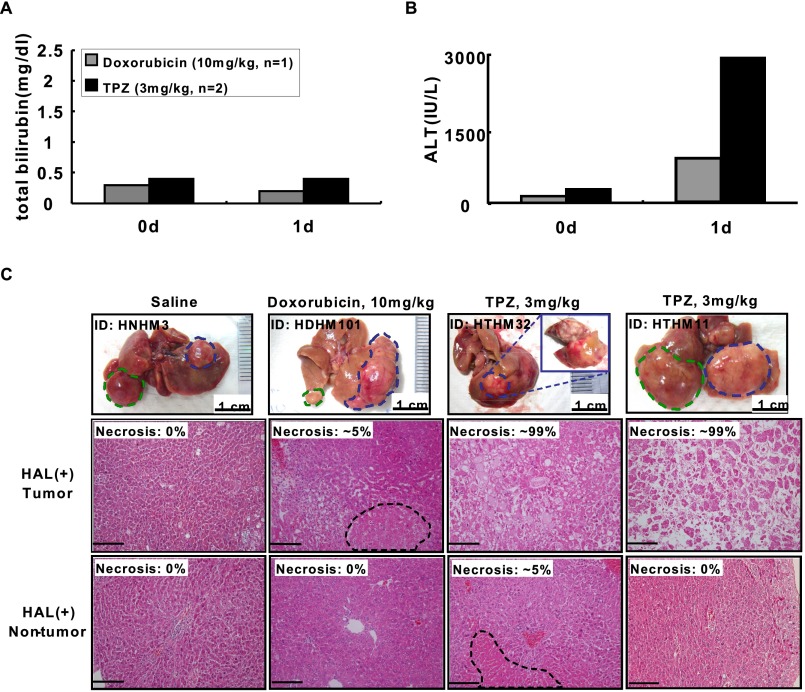

Fig. S5.

Cytotoxic effect of TPZ in combination with transient L-HAL and compared with doxorubicin. The HCC-bearing HBx transgenic mice were treated with 0.9% saline (n = 1), doxorubicin (10 mg/kg, n = 1), and TPZ (3 mg/kg, n = 2) through tail vein injection before transient L-HAL and killed at day 1. Total bilirubin (A) and ALT (B) in serum of these mice were determined. (C, Top) Representative gross appearance of the liver harvested from each treatment group of mice (blue dashed lines: the tumors in HAL-liver lobe; green dashed lines: the tumors in non-HAL-liver lobe). Representative H&E staining results of the tumor (C, Middle) and adjacent nontumor (C, Bottom) liver tissues of the HAL-liver lobe harvested from these mice, with the percent of the necrosis as indicated. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

For the follow-up analysis, the mice were killed on day 7 after treatment to evaluate the effects on the tumor. The gross appearance of the entire liver isolated from the TPZ-HAL–treated mice initially showed a distinct pale white color consistent with necrotic HCC in the left lobe. This finding was not present in the saline- or doxorubicin-treated mice (Fig. 3A). The histopathological analysis showed that only HCC treated with TPZ-HAL showed necrosis (Fig. 3B). Approximately 99% of the entire HCC underwent coagulative necrosis, including both the central and the peripheral regions (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6 A and B). In contrast, no overt histopathological changes were detected in the HCC from mice treated with saline or doxorubicin in combination with transient HAL (Fig. 3C and Fig. S6 C and D).

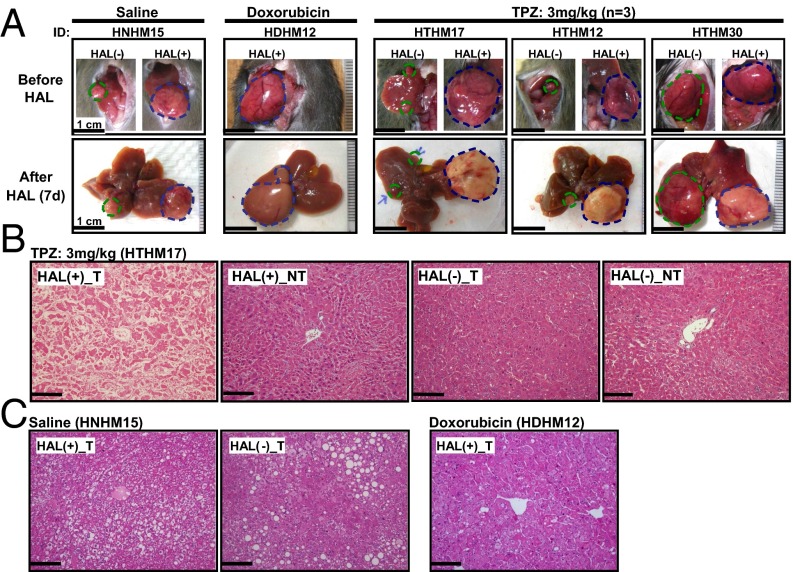

Fig. 3.

Tumor-killing effect of TPZ in HCC following transient L-HAL in the HBx transgenic mice model. The mice were treated with 0.9% saline (n = 2), doxorubicin (10 mg/kg, n = 2), or TPZ (3 mg/kg, n = 3) through tail vein injections before transient L-HAL and were killed on day 7. (A) Representative gross morphology of the liver and tumors. Tumor necrosis occurred in the HCC treated with TPZ, and transient HAL was revealed as a pale color. The blue and green dashed cycles indicate the tumor regions with and without HAL treatment, respectively. (B) Representative histopathological examination of the TPZ-treated mice. Nearly complete coagulative necrosis was observed in the left lobe HCC after treatment with the L-HAL and TPZ, but not in the HCC in the right lobe or the nontumor region. (C) No necrotic changes were detected in HCC from the groups treated with the combination of transient HAL and saline or doxorubicin. The data are representative of each independent group. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

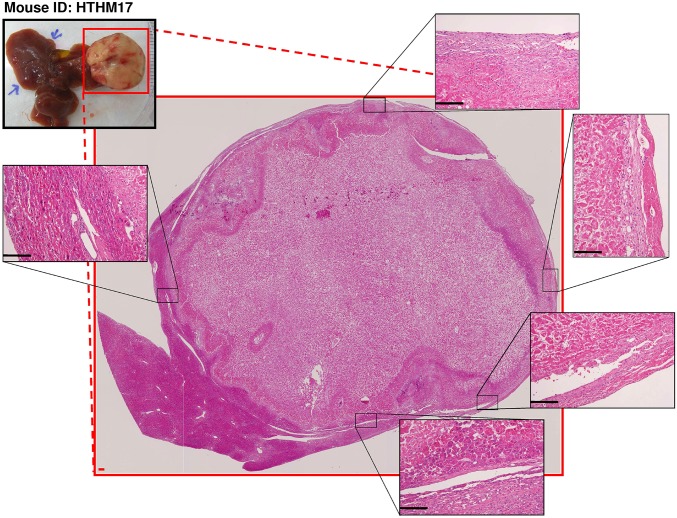

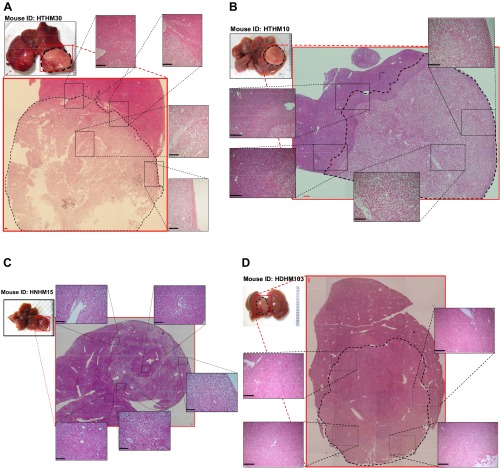

Fig. 4.

Nearly complete necrosis of an HCC tumor region of an HBx transgenic mouse after treatment with transient L-HAL and TPZ (3 mg/kg). Representative H&E staining of an HCC liver tissue sections from an HBx transgenic mouse (HTHM17) covering the whole cross-section of the tumor region. Several areas at the tumor boundary, marked by black dashed squares, are shown at a higher magnification in Insets to show that there were no detectable residual, viable tumor cells after the treatment. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

Fig. S6.

Comparison of tumor necrosis of HCC after treatment with TPZ or doxorubicin in combination with transient L-HAL. The representative H&E staining results for HCC liver tissue sections from HBx transgenic mice treated with TPZ (3 mg/kg) (A and B), 0.9% saline (C), and doxorubicin (D), in a manner covering the whole cross-section of the tumor. Several areas at the boundary or central part of the tumors marked by black dashed squares were demonstrated in a higher magnification manner in Insets. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

We noted that a few mice had HCC in some other liver lobes that did not receive TPZ and L-HAL. The histopathological analysis revealed that only the HCC in the left lobe underwent extensive tumor necrosis, whereas the HCC in other lobes remained intact (Fig. 3 A–C). As all HCC in the liver was exposed to TPZ after i.v. injection, the results indicated that TPZ alone was not effective without the hypoxia induced by L-HAL. These results confirmed that when combined with HAL, TPZ is highly effective compared with doxorubicin.

Expanding the Territory of Hypoxia Induced by the Combination of Common Hepatic Artery Ligation and Tirapazamine.

The above results indicated that TPZ can selectively kill HCC following transient HAL of the tumor-bearing liver lobe. Next, we transiently ligated the common hepatic artery (CHAL) to test whether TPZ could provide sufficient antitumor effects on HCC in a larger area of the liver. Three groups of mice were subjected to different treatments, including CHAL only, TPZ (3 mg/kg) only, and CHAL combined with TPZ (3 mg/kg). The blood flow to the tumor was reduced to nearly 25% of the baseline by CHAL, thereby establishing a hypoxic environment for the TPZ treatment (Fig. 5A).

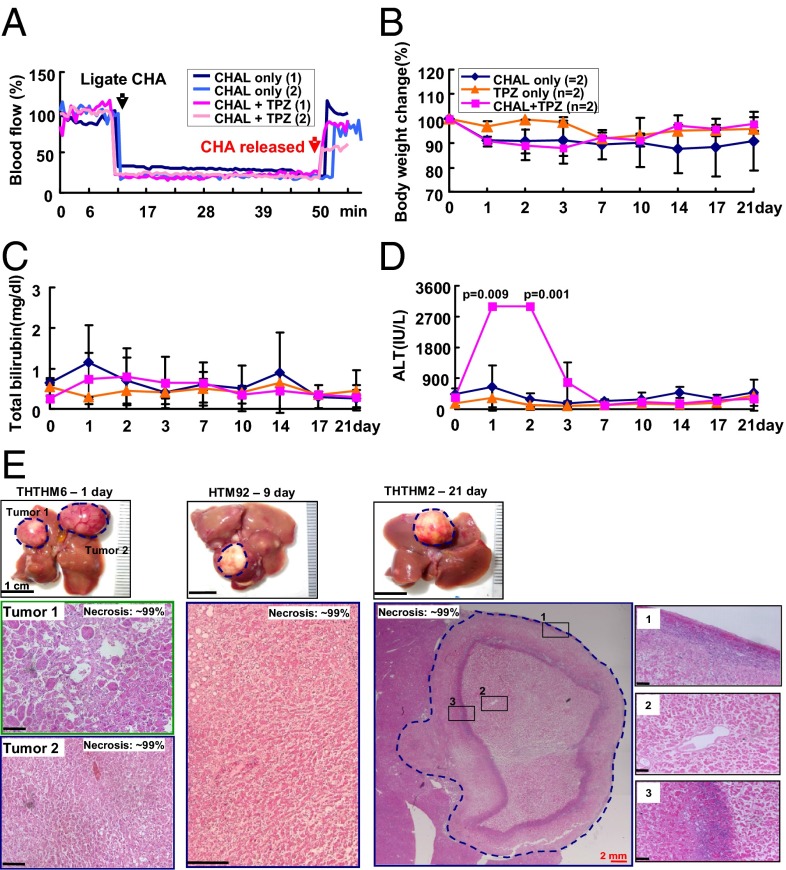

Fig. 5.

Treatment effect of transient CHAL and TPZ, alone or in combination, on HCC. (A) Transient CHAL-induced hypoxia in the HCC, as revealed by the change in blood flow to the HCC following transient CHAL with or without TPZ treatment. No significant changes in body weights (B) and the total serum bilirubin levels (C) were observed among all groups. (D) Elevation of the serum ALT levels in mice that were treated with transient CHAL and TPZ for 2 d. (E) Gross morphology and histopathological examination of the tumors in the transient-CHAL+TPZ-treated group. Tumor necrosis was first revealed by the pale color in the gross morphological examination of three mice that were treated for 1, 9, and 21 d (Upper). The H&E-stained tumor tissues from these three mice were shown in Lower. All HCC in these three mice showed nearly complete necrosis. Representative necrosis of the HCC in THTHM2 was observed throughout the cross-section of the tumor region. Several tumor boundary areas, marked by black dashed squares, were shown at a higher magnification in Insets to show that no residual, viable tumor cells were detected after the treatment. (Scale bars: black, 0.2; red, 2 mm.)

A follow-up of 1–21 d after treatment revealed that only HCC from the mice that were treated with TPZ and CHAL was killed, resulting in an estimated 99% necrosis (Fig. 5E), similar to the HCC that was treated with TPZ and L-HAL; no necrotic changes were detected in the HCC from the other two groups (Fig. S7). Near-complete necrosis was observed in all HCC from the four mice that were treated with the combination of CHAL and TPZ (Fig. 5E), except for one derived from the caudate lobe, in which the blood supply was not from the common HA, but from a separate branch of the aorta (Fig. S8).

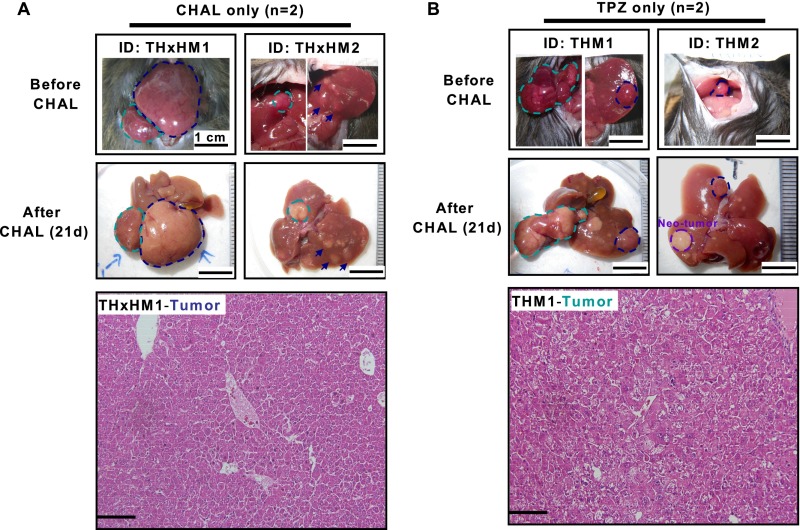

Fig. S7.

Tumor-killing effect did not occur in HCC treated with either CHAL or TPZ alone. Gross morphology and histopathology examination of the liver and tumors in transient-CHAL–treated group (n = 2) (A) and TPZ-treated group (n = 2) (B), which were killed at day 21 after treatment, without detectable necrosis in the tumor regions (marked with dashed cycles). (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

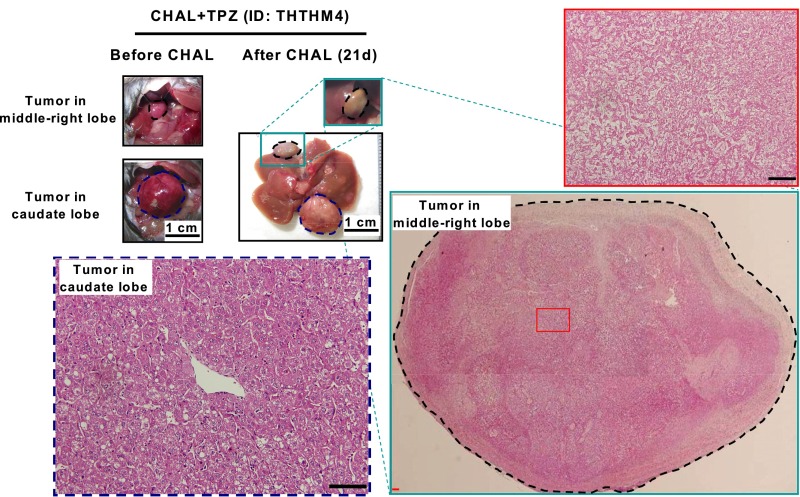

Fig. S8.

Near-complete tumor necrosis were achieved for all HCCs except the one in the caudate lobe, after treatment with CHAL and TPZ. Gross appearance and histopathology examination of two tumors in an HBx transgenic mouse treated with transient CHAL and TPZ (3 mg/kg) for 21 d. One tumor locates in middle-right lobe (marked with black dashed circle) showed near-complete necrosis (Right), but the other locates in caudate lobe (marked with blue dashed circle) did not show necrosis (Lower Left). (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

Longer Follow-Up of the Treated Mice to Determine any Recurrence.

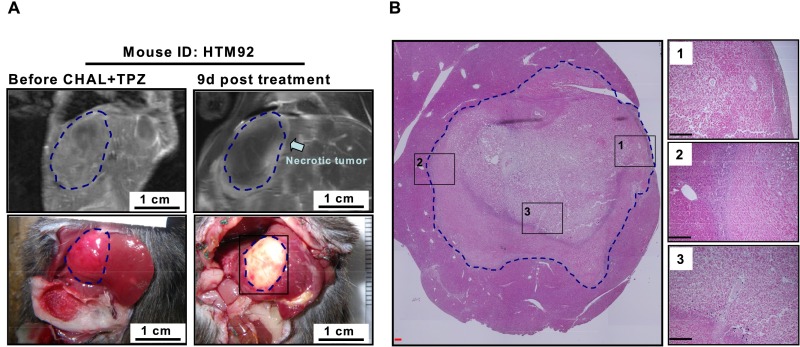

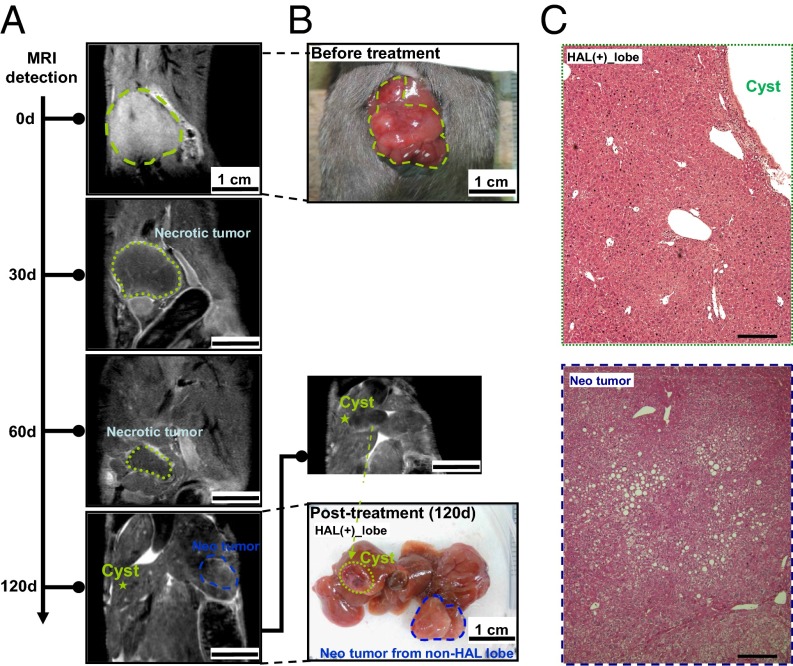

We next tried to examine the long-term effects of this combined treatment by using noninvasive imaging. The coronal contrast-enhanced liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detection platform was first established in two HCC-bearing mice undergoing TPZ and transient CHAL treatment (Fig. S9). We then showed one example of long-term follow-up after combination therapy. Before the therapy, the MRI indicated only a single HCC located in the middle-right lobe of the liver (Fig. 6A, 0 d), which was confirmed by explorative laparotomy (Fig. 6B). After the TPZ and transient HAL treatments, the HCC appeared to be necrotic, which was shown as a region with reduced signal and a clear border in the image taken at day 30 after treatment (Fig. 6A, 30 d). As time went on, the total area of necrotic HCC decreased, which was subsequently absorbed and completely disappeared by the 120th day (Fig. 6A, 60 d and 120 d). The tumor did not grow again after treatment with TPZ and transient HAL, but became cystic. H&E staining indicated a normal histology of the liver tissue at this site on the 120th day (Fig. 6C). However, both contrast MRI and gross examination revealed another new HCC growing in the non-HAL–treated liver lobe (Fig. 6A and B, Neo-tumor). This result further supports the long-term effectiveness of the combination of TPZ and HAL in the targeted lesion.

Fig. S9.

Contrast-enhanced MRI can detect the necrosis in HCC caused by TPZ combined with transient CHAL. (A) The MRI images and the gross appearance of an HCC in liver (marked in blue dashed circles), at time points before treatment (Left) and at 9 d after treatment (Right). (B) The liver tissues were collected for H&E staining, with the results shown in a manner covering the whole cross-section of the tumor region to support the near-complete necrosis after treatment. Several areas at the boundary or central parts of the tumor marked by black dashed squares were demonstrated in a higher magnification manner in Insets. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

Fig. 6.

Long-term follow-up with contrast-enhanced MRI showed that the necrotic HCC observed after treatment with TPZ and transient HAL eventually disappeared. (A) A single HCC located in the middle-right liver lobe of an HBx transgenic mouse was identified by coronal contrast-enhanced liver MRI (marked with a green dashed line at 0 d). After the combined therapy, the HCC appeared to be necrotic, as indicated by the region with a low MRI signal and clear border at 30 and 60 d (marked with green dashed line at 30 d and 60 d). The volume of this HCC decreased with time (from 0 d to 30 d and 60 d), and it was completely absorbed and disappeared at the end point (120 d). Meanwhile, another new tumor was growing in the non-HAL–treated liver lobe and was detected by contrast-enhanced MRI (marked by blue dashed circle). (B) Gross morphology of the HCC before treatment and 120 d after treatment. A cystic lesion was formed at the site of the original HCC, and a neo-tumor was identified at the end of follow-up (the green dashed circle indicates the original tumor and the blue dashed circle indicates the new tumor). (C) H&E staining for the liver tissues collected from the cystic lesion (original tumor area) and the neo-tumor. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

Discussion

In this study, we show that the pattern of blood supply to HCC in the HBx transgenic mouse model, but not in the orthotopic xenograft model, is similar to that of HCC in humans. The proof-of-principle of the induction of hypoxia in the HCC of this animal model was accomplished by using the combined OxyLite/OxyFlo probes to continuously monitor blood flow and pO2. The average pO2 of HCC in the HBx transgenic mouse model is 10 mmHg, which is equivalent to 15 μM O2 (1 mmHg = 1.5 µM O2) (20). A reduction in the blood flow to <25% of the baseline can induce hypoxia in HCC, with an average pO2 of 0.75 mmHg during the period of HAL. The physiological consequences of hypoxia, elevation of the EPO mRNA and HIF-1α protein levels, were confirmed in the target HCC at 2 h after HAL, but not in the nontumorous liver or HCC without HAL. Therefore, although the spontaneous development of HCC in HBx transgenic mice requires a lengthy period of ∼18 mo, this model is ideal for studying the therapeutic efficacy of TPZ in combination with HAL.

In clinical practice, transarterial embolization can induce hypoxia in HCC, with a progressively descending O2 gradient from the central to the peripheral region, ranging from 0.1 to 10 μM (6). The tumor regions that were exposed to lethal hypoxia (0.1–1 μM O2) were killed, and the regions that were exposed to “intermediate” hypoxia (∼1–10 μM O2) were not killed and, instead, survived and contributed to tumor regrowth. In addition, hypoxia can stabilize the cellular HIF-1α levels and can increase the transcription of several angiogenic genes to induce angiogenesis (21). Extrahepatic collateral arteries develop rapidly after hepatic artery ligation (22). After TACE, the collaterals support the residual tumor in most patients, which limits the efficacy of TACE (23). Therefore, we included TPZ, which is a bioreductive prodrug (KO2 ∼ 1 μM) (6) that can be activated at intermediate oxygen concentrations (1–10 μM O2) (24) caused by hepatic arterial embolization, as a strategy to overcome the limitation of TACE.

This hypothesis was strongly supported by our proof-of-concept experiments in HBx transgenic mice, showing superior tumor killing effect of this TPZ-TACE treatment compared with the traditional doxorubicin-TACE regimen (tumor necrosis: TPZ-TACE, mean ± SD = 98.2 ± 2.7%; doxorubicin-TACE, mean ± SD = 1.67 ± 2.89%; P < 0.001). The antitumor activities of TPZ and arterial embolization are highly synergistic with each other, showing a successful induction of tumor necrosis in ∼99% of the HCC located within the region with targeted blood supply. In the histopathological analysis, 10/11 of HCC that received this combined therapy showed 99% necrosis, including the peripheral region that may potentially obtain oxygen by diffusion from the surrounding normal liver. In the only HCC lesion showing 90% tumor necrosis, the tumor region that did not exhibit necrosis exhibited a portal triad structure (Fig. S10), indicating a dual blood supply that fails to activate TPZ. The only observed adverse event was a transient elevation of the serum ALT levels on day 1, which completely recovered afterward by day 7 after treatment. This phenomenon might be attributed to the tumor necrosis because the necrotic tumor could be clearly observed from day 1 after treatment.

Fig. S10.

The HCC region not killed by combination treatment of L-HAL and TPZ has dual blood supply from HA and PV. (A) The HCC-bearing HBx transgenic mouse (HTHM12) was treated with transient L-HAL and TPZ (3 mg/kg), which was killed at day 7 after treatment and the liver was collected for histopathologic examination. The gross appearance and overall H&E staining showed ∼90% of the tumor to be near-complete necrosis but ∼10% of the tumor remained alive (green dashed lines indicate the border between necrotic and nonnecrotic tumor regions; black dashed lines indicate the boundary of the tumor region viable after treatment). Several areas at the boundary were demonstrated in a higher magnification manner in Insets. There contains typical portal triad structure in the alive tumor region (marked by blue squares). (B) The tissue sections for the alive tumor region were processed to immunohistochemistry staining with cytokeratin 19 (CK19). As a marker for the bile duct cells in the portal triad structure, the positive signal of CK19 (marked in green arrows) supported the dual blood supply for the minor alive tumor region. (Scale bars: 0.2 mm.)

Another limitation for TACE in current clinical practice is that the embolization of HA using geofoam or lipiodol is usually only transient instead of permanent. In most cases, the obstructed HA that supplies the HCC will resume its blood flow. This observation is supported by the fact that the arteriogram performed in the second or later embolization usually showed that the previously embolized HA was no longer occluded (25). Our results showed that a transient HAL, 40–50 min (the reported half-life of TPZ), is sufficient to induce TPZ to efficiently kill the tumor cells. Therefore, we expect that TPZ will be compatible with the current clinical practice using geofoam or lipiodol for embolization, which would be sufficient to cause extensive tumor killing by TPZ although the embolization is transient. It would be interesting to test whether the combination of TPZ with hepatic embolization by DC-Beads, which causes permanent embolization (26), could further improve the tumor killing efficacy.

We noted that Sonoda et al. performed a similar study by examining the effectiveness of combining TPZ with transarterial embolization (TAE) in an implanted rabbit VX2 liver tumor model (27). However, their study did not show significant tumor killing effects of the combination treatment, which only slowed and decreased the tumor growth as shown by magnetic resonance imaging. The discrepancy could come from the different animal models and experimental protocol used in the two studies. For example, the systems that supply blood to the implanted tumor model might be different from human HCC, as revealed in our study. Meanwhile, the sarcoma origin of VX2 might not be able to reflect primary HCC. Furthermore, in their protocol, the arterial embolization with gelatin microspheres was conducted before the i.p. injection of TPZ, which might likely interfere with the delivery of TPZ into the target HCC through the artery. The spontaneous HCC model used in our present study, along with the protocol of i.v. injecting TPZ before HAL, might provide significant advantages to recapitulate the treatment of human HCC.

As revealed by our study, the safe and effective TPZ dosage that achieved ∼99% tumor necrosis in combination with HAL was determined to be 3 mg/kg. A previous human phase III study of TPZ used a dose of 290 mg/m2 (15), representing a dose of 7.8 mg/kg by mg/kg-to-mg/m2 (conversion factor of 37 for a 60-kg person) (28). According to the same formula, the safe and effective TPZ dose derived from the current study, 3 mg/kg, is equal to 0.24 mg/kg for humans, which is considerably lower than that used in previous clinical trials. However, the safe dose of TPZ might need to be adjusted when considering liver cirrhosis, which frequently coexists with HCC in humans. Only mild liver fibrosis was identified in the nontumorous region of the HBx transgenic mice, which limits our analysis to the effect of TPZ in the presence of cirrhosis. However, it is well documented that the blood supply for cirrhotic livers is contributed by both HA and PV (29). Consequently, arterial embolization is not expected to achieve sufficient hypoxia to activate the TPZ in cirrhotic livers. In fact, this hypothesis has been validated by our test in the mouse model of cirrhotic liver induced by CCl4. However, most intermediate stage HCC usually outgrows as several satellites around the main tumor. These small satellite tumors may also be perfused by the portal vein and may resist TACE or TPZ-TACE. A clinical phase I trial can be started with intermediate HCC patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis to determine the optimal dose and tolerability of i.v. TPZ to address these issues with efficacy or limitations of the current approach. Hopefully, the ongoing clinical trial combining TPZ and TAE in the appropriate HCC patients will help examine whether this TPZ-TACE regimen can be an effective therapy to increase the survival of patients with intermediate stage HCC.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and Chemicals.

TPZ (SR 4233, 3-amino-l,2,4-benzotriazine-l,4-dioxide, WIN59075, and Tirazone) was provided by Lestoni. Doxorubicin hydrochloride was obtained from National Taiwan University Hospital. TPZ and doxorubicin hydrochloride were dissolved in 0.9% sterile NaCl on the day of the tail vein injection, and the solution was protected from light until its use.

HBx Transgenic Mice and Animal Care.

The HBx transgenic mice were established as described (19). The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Taiwan University College of Medicine Laboratory Animal Center (NTUCMLAC). All of the HBx transgenic mice were bred and followed-up in a specific pathogen-free facility; the tails of individual mice were subsequently collected upon weaning at 3 wk of age for the genotyping process by using a described method (19).

HCC developed spontaneously in >95% of the male HBx transgenic mice at the age of 17–18 mo. The transgenic mice containing 0.5–2 cm in diameter tumors were used for this study. The livers in 13- to 14-mo-old HBx transgenic mice were considered at the precancerous stage, which already showed degeneration, inflammation, and even some small hyperplastic nodules, as revealed by histopathological examination (19).

Transient HAL.

The mice were subjected to left or common hepatic artery ligation for 40 min, and the silk ligation was subsequently untied. For the studies on the effects of the drugs, 0.9% saline, doxorubicin, and TPZ were injected into the tail vein of each mouse for 7 min before the hepatic artery ligation. After completion of the injection, a midline laparotomy was performed to expose the left lobe of liver and liver hilum to dissect the left or common hepatic artery for transient ligation. All mice were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of 400 mg/kg Avertin (Sigma-Aldrich) during the experiments. The liver tissues were collected for quantitative real-time PCR, Western blotting, and H&E staining, and serial serum samples were collected to evaluate the ALT and total bilirubin levels by using an ARKRAY Spotchem EZ Chemistry Analyzer SP-4430 (Arkray).

In Vivo pO2 and Blood Flow Measurements.

The tissue oxygen levels and blood flow can be directly measured by using the combined OxyLite/OxyFlo probes (Oxford Optronix). The OxyLite is a fiber-optic probe that can detect the O2-dependent fluorescent lifetime at the tip to measure pO2. The OxyFlo continuously monitors tissue blood perfusion by using laser-Doppler flowmetry. In this study, the tip size of the combined probes was ∼450 μm, and the probes were directly inserted into liver tumor or nontumor tissue of an anesthetized mouse to continuously monitor pO2 and blood flow before, during, and after ligation of the hepatic artery or both the hepatic artery and portal vein. The pO2 and blood flow signals from the probes were a 5-s average value and were recorded and analyzed with a data-acquisition system (LabChart Reader, Chart version 6 for Windows; AD Instruments).

MRI Detection.

Mice with HCC were imaged under isoflurane anesthesia (Abbott Laboratories), and contrast-enhanced MRI was acquired by using 1 mmol/kg gadobutrol (gadolinium-DO3A-butriol, Gadovist 1.0; Bayer Schering Pharma) on a 7 Tesla Animal MR Scanner (Bruker BioSpin). We performed scans before HAL as a baseline (day 0), and scans were collected every 30 d thereafter for 120 d of follow-up. The coronal image sets were collected by using the following parameters: repetition time, 1,300 ms; echo time, 9 ms; flip angle, 90°; field of view, 3 × 2.5 cm; matrix, 256 × 256; spatial resolution, 117 × 98 μm/pixel; slice thickness, 1.0 mm. The mice were killed on days 9, 13, and 120 after treatment, and the livers were processed for H&E staining.

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Line and Cell Culture.

We purchased the Huh-7 human hepatoma cell line from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center and cultured the cell line in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Biological Industries) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Gibco/Invitrogen) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Conventional Orthotopic Xenograft Model and Animal Care.

The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of NTUCMLAC. The conventional orthotopic xenograft model was generated by horizontally inoculating 5 × 106 Huh-7 cells in 30 μL of PBS into the left lobe of liver beneath the capsule of a 6- to 8-wk-old NOD-SCID mouse purchased from NTUCMLAC. After 3–4 wk, the diameter of the transplanted liver tumor grew by ∼1.5 cm and it was used for the experiments.

Hepatic Artery Ligation and Portal Vein Ligation.

For selection of the animal model, the conventional orthotopic xenograft model were subjected to ligate the left hepatic artery for 10 min and then ligate the left portal vein for 10 min by using a silk thread. All mice were anesthetized with i.p. injection of 400 mg/kg avertin (Sigma-Aldrich) during experiments. The liver tissues were collected for Western blotting.

Mouse Model of Liver Fibrosis.

Eight-week-old male C57/B6 mice (National Laboratory Animal Center) were treated with CCl4 (2 μL/g body weight; 1:4 dilution with corn oil) by i.p. injection at 3-d intervals for a total of 12 injections. Three days after the last CCl4 injection, the mice were treated with 0.9% saline and two doses of TPZ, 3 and 20 mg/kg, through tail vein injections before transient L-HAL. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of NTUCMLAC.

The establishment of liver fibrosis was examined by analyzing the TIMP-1 levels in serum and by Sirius Red staining of the liver tissues. The TIMP-1 levels were determined by using Quantikine mouse TIMP-1 ELISA kit (R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mouse liver tissues were fixed overnight in 10% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and the sections were subjected to Sirius Red staining and histological analysis.

Immunohistochemistry Staining.

Liver tissues were freshly fixed in 10% formalin, and then embedded in paraffin for subsequent tissue section preparation. Liver sections at 3 μm were prepared for immunohistochemistry staining to detect the signal of cytokeratin 19 (CK19) [diluted 1:50 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology)] by the N-Histofine Polymer Detection System Kit (Nichirei Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of the Human and Mouse EPO mRNA Levels.

The total RNA from mouse hepatic tissue was extracted by using a TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and 1 μg of RNA was processed for reverse transcription using the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted by using the LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I Kit in a LightCycler PCR machine (Roche). The PBGD (porphobilinogen deaminase) gene was amplified for each sample in the same run as an internal control for the relative quantification. The primers used for specific amplification of the EPO and PBGD genes were as follows. Human EPO: forward primer: 5′-TCTATGCCTGGAAGAGGATGG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GTGTCAGCAGTGATTGTTCGG-3′. Human PBGD: forward primer: 5′-CATGAAGATGGCCCTGAGGAT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GGCATCTGTGCCCCACAAACCAG-3′. Mouse EPO: forward primer: 5′-ACTCTCCTTGCTACTGATTCCTC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GCCTGTTCTTCCACCTCCATTC-3′. Mouse PBGD: forward primer: 5′-TGAAGGATGTGCCTACCATACTA-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GAGGTTTCCCCGAATACTCTTGA-3′. Cp values were determined by using the second derivative maximum methodology, and the detailed procedures for the quantification were similar to those described in our previous study (19).

Detection of Tissue Hypoxia Using the Hypoxyprobe-1 Kit.

The Hypoxyprobe-1 solution (Natural Pharmacia International) containing solid pimonidazole HCl was injected into the HCC-bearing HBx transgenic mice via the tail vein (60 mg/kg body weight) for 10 min before L-HAL. The mice were then killed 15 min after L-HAL. The control mice without L-HAL were killed 25 min after the injection with the hypoxyprobe. The nontumorous and tumorous liver tissues were processed for IHC staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The affinity-purified rabbit anti-pimonidazole Ab (PAb2627AP) was used to detect the adducts formed by the covalent binding of pimonidazole to the thiol groups in proteins, which was specifically observed in the hypoxic cells (30).

Western Blot Analysis.

Total protein was extracted from the liver tissue by homogenizing the tissue in 8 M urea lysis buffer that had been freshly supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. We centrifuged the crude lysates at 15,000 rpm (20,630 × g; AT-2724M rotor, KUBOTA 5922, Tokyo) for 30 min and quantified the protein concentration by using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Sixty micrograms of proteins were separated on 10% SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF-1α antibody [diluted 1:1,000 (Novus Biologicals)] and mouse monoclonal anti–β-actin [diluted 1:10,000 (Sigma-Aldrich)]. The proteins were detected by using enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Statistical Analysis.

The EPO mRNA levels in the liver tissues collected before and after HAL; the ALT levels and tumor necrosis (%) in the different treatment groups of mice were compared and analyzed by using two-sided Student’s t tests. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All analyses were performed by using Stata statistical software (version 12.0; Stata).

Histological and Morphometric Analysis of Tumor Necrosis.

For each mouse, the liver tissue containing the whole tumor and the adjacent nontumorous region was fixed in 10% formaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. The liver tissue sections (5-µm thickness) encompassing the whole tumor were stained with H&E for the histological analysis. The percentage of necrosis in each tumor was quantified by dividing the necrotic area by the total tumor area in five cross-sections covering the whole tumor, using ImageJ software (Version 1.46r, National Institutes of Health).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a collaboration project with Lestoni company and by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan Grants MOST 103-2321-B-002-025 and MOST 104-2314-B-002-023-MY3.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1613466113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lencioni R, Chen XP, Dagher L, Venook AP. Treatment of intermediate/advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the clinic: How can outcomes be improved? Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 4):42–52. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu L, et al. Hepatic artery injection of ¹³¹I-labelled metuximab combined with chemoembolization for intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective nonrandomized study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39(8):1306–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautt WW, Greenway CV. Conceptual review of the hepatic vascular bed. Hepatology. 1987;7(5):952–963. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodd GD, 3rd, et al. Minimally invasive treatment of malignant hepatic tumors: At the threshold of a major breakthrough. Radiographics. 2000;20(1):9–27. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.1.g00ja019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(6):393–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian J, Feng GS, Vogl T. Combined interventional therapies of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(9):1885–1891. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i9.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forner A, Gilabert M, Bruix J, Raoul JL. Treatment of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(9):525–535. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders MP, Patterson AV, Chinje EC, Harris AL, Stratford IJ. NADPH:cytochrome c (P450) reductase activates tirapazamine (SR4233) to restore hypoxic and oxic cytotoxicity in an aerobic resistant derivative of the A549 lung cancer cell line. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(3):651–656. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JM. SR 4233 (tirapazamine): A new anticancer drug exploiting hypoxia in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 1993;67(6):1163–1170. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le QT, et al. Phase II study of tirapazamine, cisplatin, and etoposide and concurrent thoracic radiotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: SWOG 0222. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):3014–3019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craighead PS, Pearcey R, Stuart G. A phase I/II evaluation of tirapazamine administered intravenously concurrent with cisplatin and radiotherapy in women with locally advanced cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(3):791–795. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00720-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rischin D, et al. Tirapazamine, Cisplatin, and Radiation versus Fluorouracil, Cisplatin, and Radiation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer: A randomized phase II trial of the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG 98.02) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(1):79–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maluf FC, et al. Phase II study of tirapazamine plus cisplatin in patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(3):1165–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rischin D, et al. Tirapazamine, cisplatin, and radiation versus cisplatin and radiation for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (TROG 02.02, HeadSTART): A phase III trial of the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):2989–2995. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang WJ, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein enhances the transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor through c-Src and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta kinase pathways. Hepatology. 2009;49(5):1515–1524. doi: 10.1002/hep.22833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plock J, et al. Activation of non-ischemic, hypoxia-inducible signalling pathways up-regulate cytoprotective genes in the murine liver. J Hepatol. 2007;47(4):538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy AS, et al. Proliferation and hypoxia in human squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: First report of combined immunohistochemical assays. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37(4):897–905. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu BK, et al. Blocking of G1/S transition and cell death in the regenerating liver of Hepatitis B virus X protein transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340(3):916–928. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiarotto JA, Hill RP. A quantitative analysis of the reduction in oxygen levels required to induce up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA in cervical cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(10):1518–1524. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407(6801):249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koehler RE, Korobkin M, Lewis F. Arteriographic demonstration of collateral arterial supply to the liver after hepatic artery ligation. Radiology. 1975;117(1):49–54. doi: 10.1148/117.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung JW, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: Prevalence and causative factors of extrahepatic collateral arteries in 479 patients. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7(4):257–266. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2006.7.4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch CJ. Unusual oxygen concentration dependence of toxicity of SR-4233, a hypoxic cell toxin. Cancer Res. 1993;53(17):3992–3997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geschwind JF, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of liver tumors: Effects of embolization protocol on injectable volume of chemotherapy and subsequent arterial patency. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):111–117. doi: 10.1007/s00270-002-2524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varela M, et al. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: Efficacy and doxorubicin pharmacokinetics. J Hepatol. 2007;46(3):474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonoda A, et al. Enhanced antitumor effect of tirapazamine delivered intraperitoneally to VX2 liver tumor-bearing rabbits subjected to transarterial hepatic embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34(6):1272–1277. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freireich EJ, Gehan EA, Rall DP, Schmidt LH, Skipper HE. Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(4):219–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huet PM, Du Reau A, Marleau D. Arterial and portal blood supply in cirrhosis: A functional evaluation. Gut. 1979;20(9):792–796. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.9.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morani A, et al. Lung dysfunction causes systemic hypoxia in estrogen receptor beta knockout (ERbeta-/-) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(18):7165–7169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]