Significance

Recombination-activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG1/2) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) create dsDNA breaks at recombination signal sequences (RSSs), initiating the variable, diversity, and joining [V(D)J] recombination pathway for antigen–receptor gene assembly. We have discovered that RAG complex binds and bends RSS DNA at the heptamer, with different binding modes for 12RSS and 23RSS substrates. Our experimentally derived binding kinetics have established that binding, bending, and synapsis precede catalysis. We have also directly observed the dynamics of the synaptic complex, revealing that RAG1/2 bending places the nonamers at nearly perpendicular orientations and that the RAG:12RSS:23RSS synaptic complex is very stable. We provide a kinetic model that integrates physical binding, bending, and synapsis steps of the RAG1/2 pathway.

Keywords: V(D)J recombination, recombination-activating gene, single-molecule FRET, immunoglobulin, antigen receptor gene

Abstract

Single-molecule FRET (smFRET) and single-molecule colocalization (smCL) assays have allowed us to observe the recombination-activating gene (RAG) complex reaction mechanism in real time. Our smFRET data have revealed distinct bending modes at recombination signal sequence (RSS)-conserved regions before nicking and synapsis. We show that high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) acts as a cofactor in stabilizing conformational changes at the 12RSS heptamer and increasing RAG1/2 binding affinity for 23RSS. Using smCL analysis, we have quantitatively measured RAG1/2 dwell time on 12RSS, 23RSS, and non-RSS DNA, confirming a strict RSS molecular specificity that was enhanced in the presence of a partner RSS in solution. Our studies also provide single-molecule determination of rate constants that were previously only possible by indirect methods, allowing us to conclude that RAG binding, bending, and synapsis precede catalysis. Our real-time analysis offers insight into the requirements for RSS–RSS pairing, architecture of the synaptic complex, and dynamics of the paired RSS substrates. We show that the synaptic complex is extremely stable and that heptamer regions of the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates in the synaptic complex are closely associated in a stable conformational state, whereas nonamer regions are perpendicular. Our data provide an enhanced and comprehensive mechanistic description of the structural dynamics and associated enzyme kinetics of variable, diversity, and joining [V(D)J] recombination.

Variable, diversity, and joining [V(D)J] recombination is essential for Ig and T-cell receptor (TCR) formation and occurs by rearrangement of variable exon regions during lymphocyte development. Complete exons are assembled from (V), (D), and (J) segments at the Ig and TCR loci. Cutting, rearranging, and recombining the few hundred preexisting (V), (D), and (J) segments can lead to millions of permutations and a highly diverse repertoire of antigen receptors and antibodies (1–4).

The recombination-activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG1/2) are lymphocyte-specific proteins that mediate recognition and splicing of (V), (D), and (J) segments. The RAG complex, which consists of RAG1/2 and the cofactor high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), creates DNA double-strand breaks at recombination signal sequences (RSSs) that flank (V), (D), and (J) segments. All RSSs have conserved heptamer and nonamer regions separated by either 12 or 23 bp (12RSS or 23RSS) and act as specific targets for RAG1/2-mediated catalytic activity. It is thought that catalytic activity and initiation of the V(D)J pathway consists of three distinct steps. First, the RAG complex binds and nicks a single RSS substrate to create a single RSS complex (SC). Next, two partner RSSs, generally a 12RSS and 23RSS, synapse to form a paired complex (PC). Finally, RAG1/2 cleaves both RSSs through a transesterification reaction, resulting in hair pinned coding ends that are repaired by nonhomologous end joining (5–12). Whether nicking occurs before or after synapsis is unclear, as is the stability of the synaptic complex (PC). Kinetic studies favor synapsis formation before nicking and a very high stability of the synaptic complex, once formed, but these concepts are based on bulk solution (ensemble) studies, and the specific steps of the reaction mechanism are uncertain due to inevitable averaging (13).

Recently, crystallography and electron microscopy techniques have been used to resolve the structures of the SC and PC (14, 15). Although these studies provide new insights into the mechanism of the RAG complex and its structural functionality, the explicit steps, related conformational dynamics, and molecular choreography involved in this intricate process remain undefined. Here we apply single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) and single-molecule colocalization (smCL) microscopy techniques to determine the real-time activity of the RAG complex in V(D)J recombination (see SI Introduction). Single-molecule approaches are particularly advantageous in resolving important molecular features that are otherwise masked due to averaging in ensemble-based assays (16). We therefore probed the conformational dynamics of RSS DNA induced by the binding of RAG1/2 and HMGB1 using smFRET and revealed distinct bending modes of the RSS substrates at their conserved regions. The binding kinetics of fluorescently labeled RAG1/2 was derived from smCL assays, showing that binding stability is enhanced in the presence of a second RSS. Finally, using smFRET capture assays, we characterized 12/23RSS synapsis and the internal dynamics of the PC. This showed a tight heptamer–heptamer association accompanied by RSS bending, thus placing the nonamers at a nearly perpendicular orientation. We find that RAG binding, bending, and synapsis precede catalysis and that the synaptic complex is very stable. Together, our findings provide a comprehensive mechanistic depiction of the structural dynamics and associated enzyme kinetics of RAG complex-mediated V(D)J recombination.

SI Introduction

Throughout this study, we have used both smFRET and smCL assays to probe the RAG complex reaction mechanism in real time. SmFRET is a biophysical tool that monitors the dynamics of individual proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. This technique relies on a pair of fluorophores where the emission spectrum of one fluorophore, termed the donor, overlaps with the absorption spectrum of another fluorophore, termed the acceptor. By simultaneously measuring the emission from donor and acceptor fluorophores, users can determine the amount of energy transfer between these two molecules. Changes in FRET value indicate changes in the distance between the donor and acceptor fluorophores, allowing FRET to act as a spectroscopic ruler that measures DNA conformational changes and DNA–protein interactions (34).

In addition to smFRET techniques, our smCL assays enabled us to visualize RAG1/2 and the DNA substrate it binds. Previous studies have used smCL techniques for kinetic characterization (35). For our assays, we used AF546-labeled RAG1/2 and Cy5-labeled DNA and examined colocalization (and not FRET) between the two fluorescent molecules. Due to the limited evanescent field of TIRF microscopy and the diffusion rates of proteins in solution, green intensity was only detected when RAG1/2AF546 interacted with surface-tethered DNA substrates. Therefore, we were able to directly measure RAG1/2 dwell times and determine rate constants that were previously based on indirect methods.

Results

RAG Complex Induces Conformational Changes in 12RSS and 23RSS DNA.

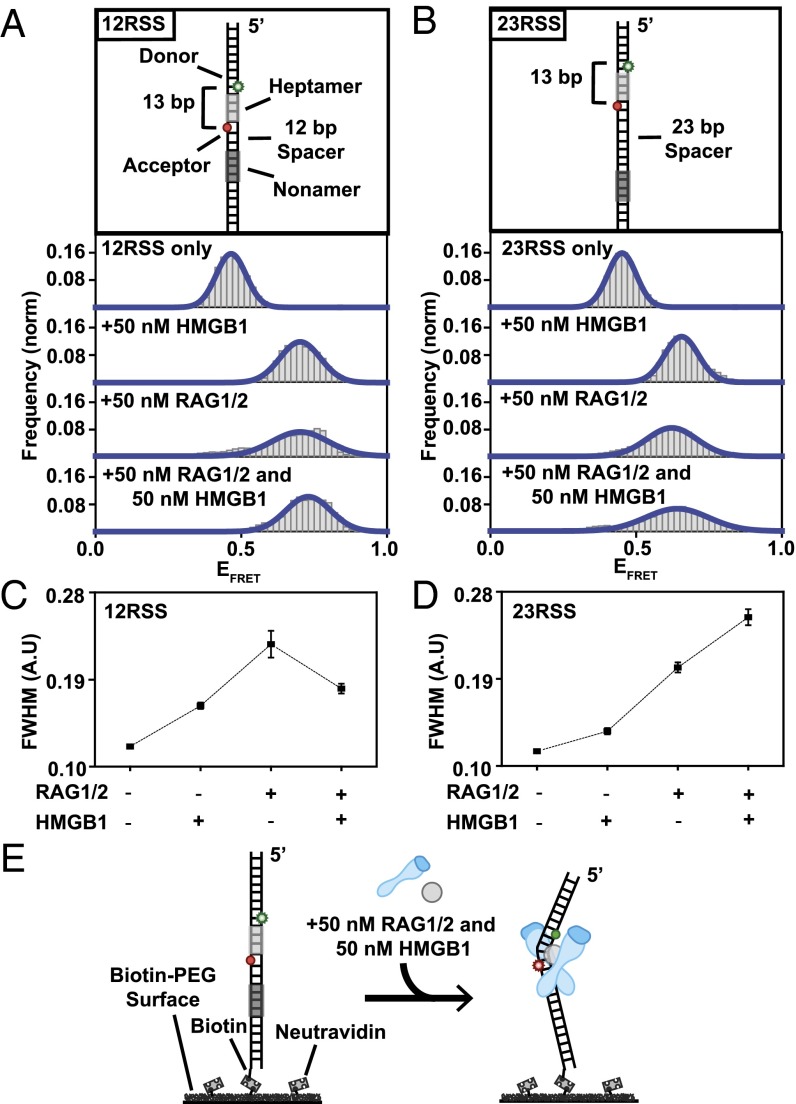

To probe RSS conformational changes associated with the binding of RAG complex to RSS sites (called single RSS complexes or SC formation), FRET probes were designed with donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) molecules flanking the heptamer region (Fig. 1 A and B). The placement of the donor and acceptor molecules in this configuration resulted in a FRET efficiency of ∼0.45 (DNA only) (Fig. S1A). Upon addition of 50 nM HMGB1, both the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates showed substantial increases in their FRET distribution, with a mean FRET value of ∼0.75. This transition to high FRET reflects the DNA bending capability induced by HMGB1 even in the absence of RAG1/2 (17). Bending was not limited to RSS substrates and was also observed with dsDNA substrates that lacked heptamer and nonamer regions, highlighting the nonspecific nature of HMGB1-induced DNA bending (Fig. S1 C–E). We note that the dsDNA bending referred to throughout this study is broadly defined and consists of the coupled twisting and bending of the double helix, which would result in a change in FRET (18).

Fig. 1.

RSS conformational changes in the SC. (A and B) Illustrations of RSS DNA FRET substrates are located above their respective histograms. Both 12RSS and 23RSS substrates display a clear shift to high FRET upon addition of 50 nM HMGB1, 50 nM RAG1/2, and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex in the presence of Mg2+. Histograms were generated after subtracting the zero FRET values and truncating photobleached portions of FRET trajectories. A minimum of 75 smFRET trajectories were used to generate each histogram. (C and D) Calculated FWHM values for RSS substrates using Gaussian fit: (C) 12RSS displayed an increase in FWHM upon addition of 50 nM RAG1/2, indicating more dynamic trajectories. The peak is narrowed upon addition of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex, implying HMGB1 stabilization of the high-FRET conformation. (D) 23RSS substrate maintained broad histograms upon addition of 50 nM RAG1/2 and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex, indicating a lack of HMGB1-stabilization of the RAG complex at the heptamer and different binding modes for the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates. (E) Illustration of RAG–HMGB1 complex-mediated bending of RSS substrates.

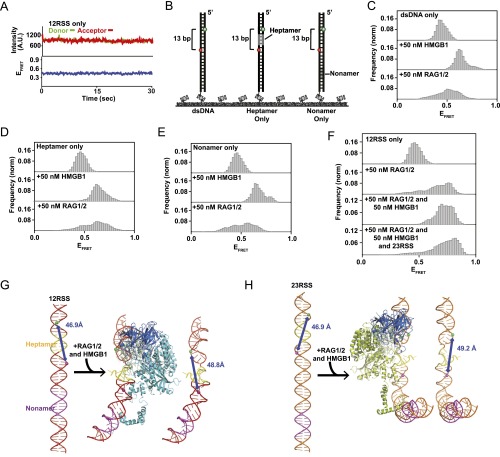

Fig. S1.

Specificity of the RAG complex reaction. (A) Representative smFRET trajectory for the DNA-only condition (12RSS). (B) Illustrations of substrates used to evaluate RAG complex specificity: dsDNA (Left), heptamer only (Middle), and nonamer only (Right). (C–E) FRET histograms of the substrates shown under different reaction conditions. The presence of 50 nM HMGB1 causes a high-FRET (bent) state regardless of conserved regions. RAG1/2 needs both heptamer and nonamer regions to effectively induce bending of the substrate. (F) FRET histograms of the 12RSS substrate under different reaction conditions. From Top to Bottom: DNA only, 50 nM RAG1/2, 50 nM RAG-HMGB1 complex, and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex with 1 nM 23RSS substrate. In the presence of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex and 1 nM 23RSS substrate (Mg2+) and upon PC formation, 12RSS shows similar bending patterns to the SC. (G and H) Modeling SC conformational changes. The distances between FRET pairs in the 12RSS (G) and 23RSS (H) substrates were calculated using recent cryo-EM structures (PDB ID code 3JBW). These distances corresponded well with our experimentally determined FRET values for the SC. In the middle structure in G, one RAG1 molecule (chain C) and 23RSS were omitted. In the middle structure in B, one RAG1 molecule (chain A) and 12RSS were omitted.

Addition of 50 nM RAG1/2 led to an increase in FRET distribution to a mean value of ∼0.75 for the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates (Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. S2 A and B). The transitions to high FRET that occurred under noncatalytic conditions (Ca2+), when both nicking and hairpin formation are inhibited (5), prompted the conclusion that Mg2+ does not limit the bending step but rather modulates subsequent catalytic activity (Fig. S2 A and B). Transitions to high FRET for substrates in the presence of Mg2+ are consistent with RAG1/2-induced bending of both 12RSS and 23RSS substrates previously reported in ensemble (i.e., bulk solution) studies (Fig. 1 A and B) (19, 20). The observed bending induced by RAG1/2 differed from HMGB1 activity in two distinct ways: specificity and stability. Unlike HMGB1, RAG1/2 was unable to bend dsDNA lacking an RSS as efficiently as RSS DNA, suggesting an RSS-specific conformational change (Fig. S1C). Although there were some FRET fluctuations upon addition of 50 nM RAG1/2 to dsDNA, the broad range of dynamics and lack of distinct FRET peaks (other than the sustained DNA-only value) indicate that any transitions visualized are most likely nonspecific and minor interactions between RAG1/2 and non-RSS DNA. Additionally, full width at half maximum (FWHM) analysis of FRET histograms showed that RAG1/2 populations had a broader FRET distribution than HMGB1 populations, representing a less stable conformational change and rapid bending fluctuations (Fig. 1 C and D). To determine HMGB1’s role as a cofactor, we conducted experiments with both 50 nM RAG1/2 and 50 nM HMGB1 in solution. Previous studies have hypothesized roles for HMGB1 in stabilizing the RAG1/2 nucleoprotein complex and increasing RAG1/2 binding affinity for RSS substrates (21, 22). We found that FRET distribution for the 12RSS substrate was narrowed in the presence of RAG–HMGB1 complex in comparison with RAG1/2-only conditions (Fig. 1C). Narrowing of the high-FRET peak may indicate less dynamic bending of the RSS heptamer region due to HMGB1-induced stabilization of the bent conformation (Fig. 1E). We note that changes in FRET distributions can also stem from a change in the distribution of values stably displayed by individual molecules. Our FRET value obtained for the 12RSS- and 23RSS-SC is in broad agreement with recent cryo-EM structures (Fig. S1 G and H) (14).

Fig. S2.

RSS DNA bending kinetics under noncatalytic conditions. (A and B) Representative smFRET trajectories for 12RSS (A) and 23RSS (B) substrates in the presence of 50 nM RAG1/2 (Ca2+) (Top) and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex (Ca2+) (Bottom). (C and D) Generated TDP matrices for 12RSS and 23RSS with different proteins and ions in solution. Color intensity corresponds to transition probability. The y axis and x axis represent the FRET values before and after the transition, respectively. Transitions above the diagonal display unbending (high to low FRET) transitions and below the diagonal display bending (low to high FRET) transitions.

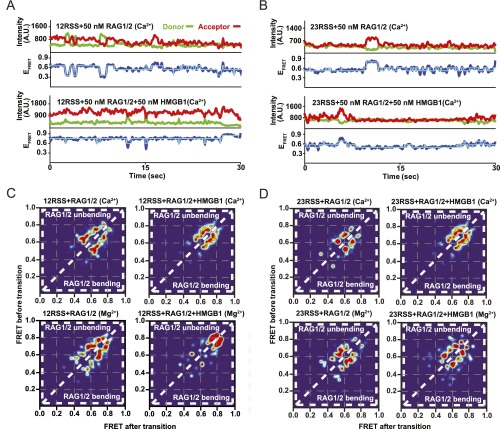

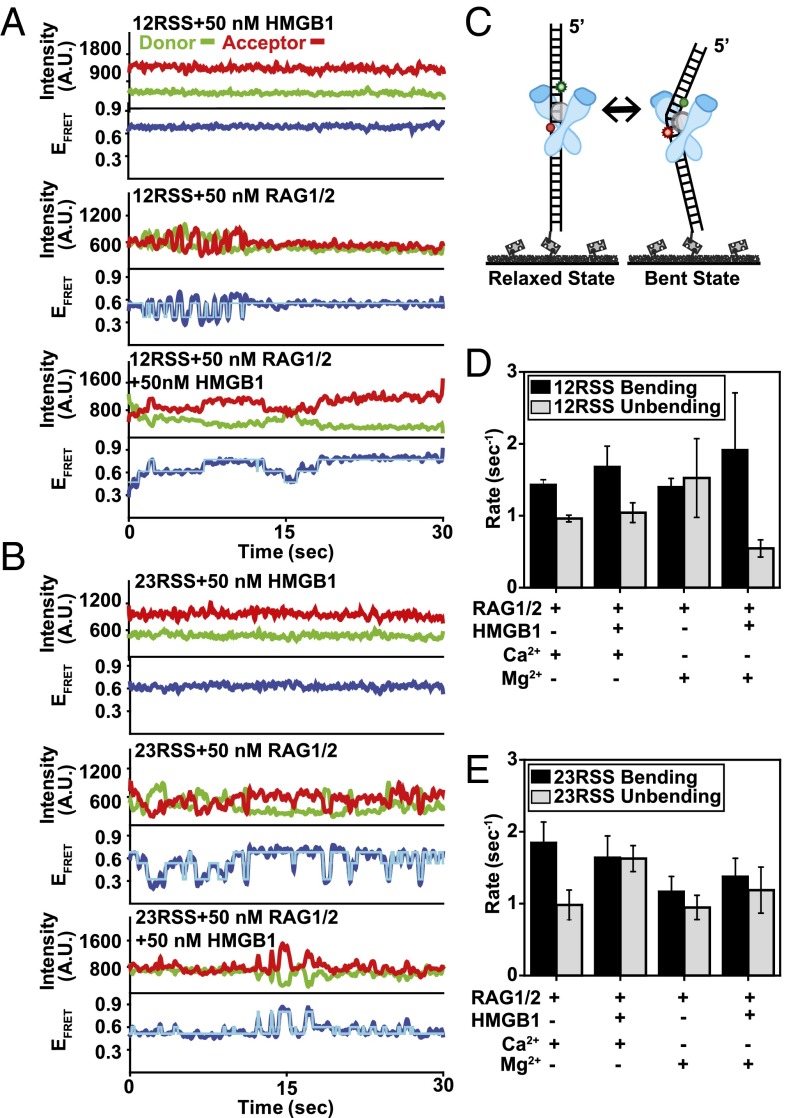

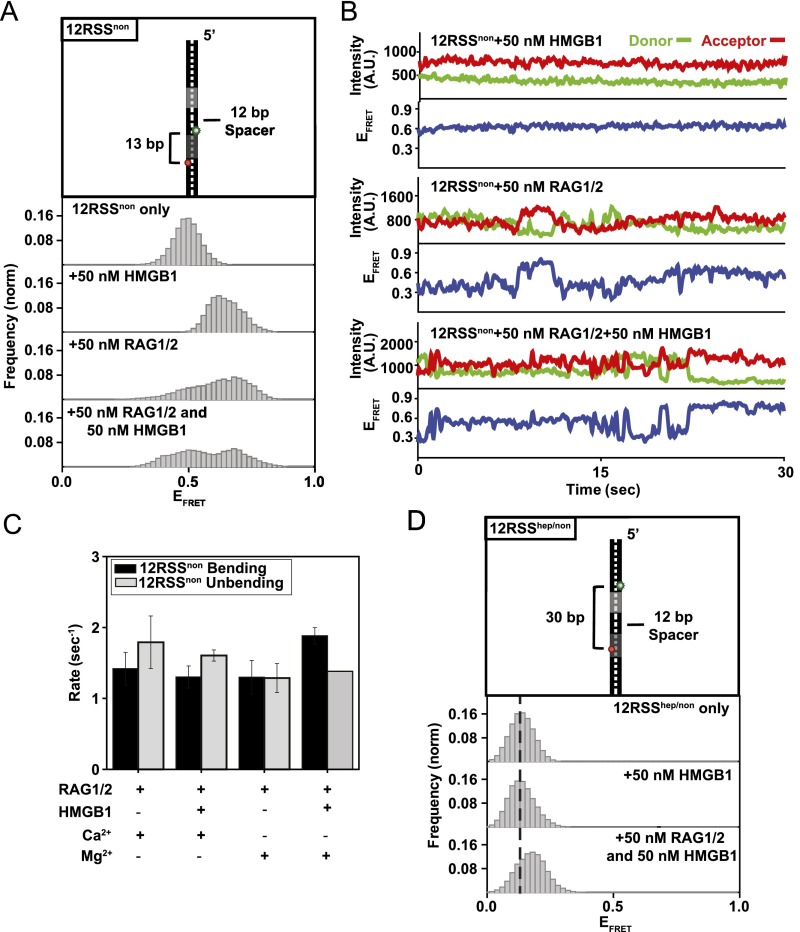

To further characterize the RAG–HMGB1 complex-induced bending conformation of the RSS heptamer region, we focused on features we observed in individual smFRET trajectories. Representative trajectories for 12RSS (Fig. 2A) and 23RSS (Fig. 2B) substrates were obtained in the presence of 50 nM HMGB1, 50 nM RAG1/2 (Mg2+), or both (Fig. 2 A and B, Top, Middle, and Bottom, respectively). The binding of HMGB1 led to persistent high FRET (Fig. 2 A and B, Top), indicative of stable bending of the heptamer region. In contrast, the presence of RAG1/2 and RAG–HMGB1 complex (RAG1/2+HMGB1) (Fig. 2 A and B, Middle and Bottom, respectively) resulted in rapid changes in FRET value, characteristic of dynamic transitions between bent and relaxed RSS conformations (Fig. 2C). Importantly, these dynamics were also prevalent under noncatalytic conditions in the presence of Ca2+ and therefore stem from RAG1/2 binding to DNA rather than any catalysis that might occur in the presence of Mg2+ but not Ca2+ (Fig. S2 A and B).

Fig. 2.

Conformational dynamics of the SC and evaluation of HMGB1 stabilization. (A and B) Representative smFRET trajectories for 12RSS (A) and 23RSS (B) substrates in the presence of 50 nM RAG1/2, 50 nM HMGB1, and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex (Mg2+) shown in the Top, Middle, and Bottom trajectories, respectively. For each smFRET trajectory, the top panel displays donor (green) and acceptor (red) intensities and the bottom panel displays the corresponding FRET efficiency (EFRET) in blue. HMM fit is in cyan. (C) Illustration of RSS substrate transitioning between the low-FRET (relaxed) state and the high-FRET (bent) state. (D and E) Calculated mean binding and dissociation rates for 12RSS (D) and 23RSS (E) substrates with different proteins and ions in solution (error bars, s.e.m.; n > 20 for all measurements).

To quantify the dynamics of these trajectories, we preformed Hidden Markov Model (HMM) analysis, yielding the transition rates between specific FRET states (23). Trajectories resulting from HMM analysis could be superimposed onto smFRET trajectories to demonstrate their correlation with the original trajectories and to exemplify the existence of well-defined states (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S2 A and B). Using the extracted frequency and transition rates for each FRET state, we constructed 2D transition density plots (TDPs) (Fig. S2 C and D). From these plots, we derived the mean rates of transition from low-to-high and high-to-low FRET states (termed bending and unbending, respectively) for the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates (Fig. 2 D and E). Addition of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex in the presence of Mg2+ significantly decreased the rate of 12RSS unbending at the heptamer (Fig. 2D). This highlights a longer dwell time in the high-FRET (bent) state and confirms stabilization of the SC at the heptamer by HMGB1 under catalytic conditions. These changes were not observed at the heptamer region of the 23RSS substrate, demonstrating that HMGB1-bending stabilization of the heptamer is specific to 12RSS (Fig. 2E). Moreover, we found that RAG1/2-induced conformational changes of the 12RSS were maintained in the presence of 23RSS, consistent with similar bending patterns in the SC and PC (Fig. S1F).

We next sought to define the conformational changes occurring in the nonamer region and between the conserved regions in the presence of RAG complex proteins. To measure conformational changes in the nonamer region and between nonamer and heptamer regions, we used 12RSS DNA substrates with FRET pairs flanking the nonamer region or FRET pairs positioned at both heptamer and nonamer regions (Fig. S3 A and D). Similar to the behavior observed for the heptamer region (Figs. 1 and 2), the nonamer region displayed an increase in FRET or bending upon addition of RAG complex proteins (Fig. S3A). SmFRET trajectories confirmed that nonamer bending was persistent for HMGB1 but dynamic in the presence of 50 nM RAG1/2 and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex (Fig. S3B). The combined effect of both HMGB1 and RAG1/2 at the nonamer resulted not in the high-FRET bending modes observed for either HMGB1 or RAG1/2 but rather in a high-FRET bent mode as well as an intermediate (nonbent) FRET mode. This result suggested that when RAG1/2 and HMGB1 bind together, their combined behavior may attribute to the reorganization of the complex and destabilization of bending at the nonamer. Although both the heptamer and nonamer are necessary for RAG1/2 bending at the RSS heptamer (Fig. S1 D and E), destabilization of bending at the nonamer by RAG–HMGB1 complex would allow for HMGB1-induced stabilization at the heptamer (Fig. S3C). HMGB1 could act as a cofactor by localizing RAG1/2 to its targeted nicking and cleavage site, which is 5′ with respect to the heptamer region. We conclude that the heptamer is the pivotal point of bending. We also note that the combined bending induced by the RAG–HMGB1 complex within the RSS region is substantial enough to bring nonamer and heptamer regions within FRET range of each other (Fig. S3D), which is in agreement with previous ensemble measurements (19, 20).

Fig. S3.

RAG complex-induced conformational changes at the nonamer region. (A) Illustration of the nonamer FRET substrate is shown above its histogram. Similar to the trends observed at the heptamer, addition of 50 nM HMGB1 resulted in a shift to higher FRET value, highlighting bending of the nonamer region. Addition of 50 nM RAG1/2 resulted in a shift to higher FRET and broadening of the FRET peak, indicating dynamic bending at the nonamer region. In the presence of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex, two distinct FRET populations were observed, corresponding to stable bending states. (B) Representative smFRET trajectories of the nonamer substrate in the presence of 50 nM RAG1/2 (Top), 50 nM HMGB1 (Middle), and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex (Mg2+) (Bottom). The presence of both 50 nM RAG1/2 and 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex cause dynamic fluctuations in the FRET value. (C) Calculated mean binding and dissociation rates for 12RSSnon substrate with different proteins and ions in solution (error bars, s.e.m.; n > 20 for all measurements). (D) Illustration of substrate used to probe the bending of the entire 12RSS region, with donor and acceptor molecules located at the heptamer and nonamer regions, respectively. The FRET histograms show that addition of 50 nM HMGB1 does not cause enough bending to change the FRET value. In contrast, the presence of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex causes the whole RSS to bend. This brings the heptamer and nonamer regions closer together, resulting in a shift of the FRET peak to a higher value.

Binding Kinetics of the RAG Complex.

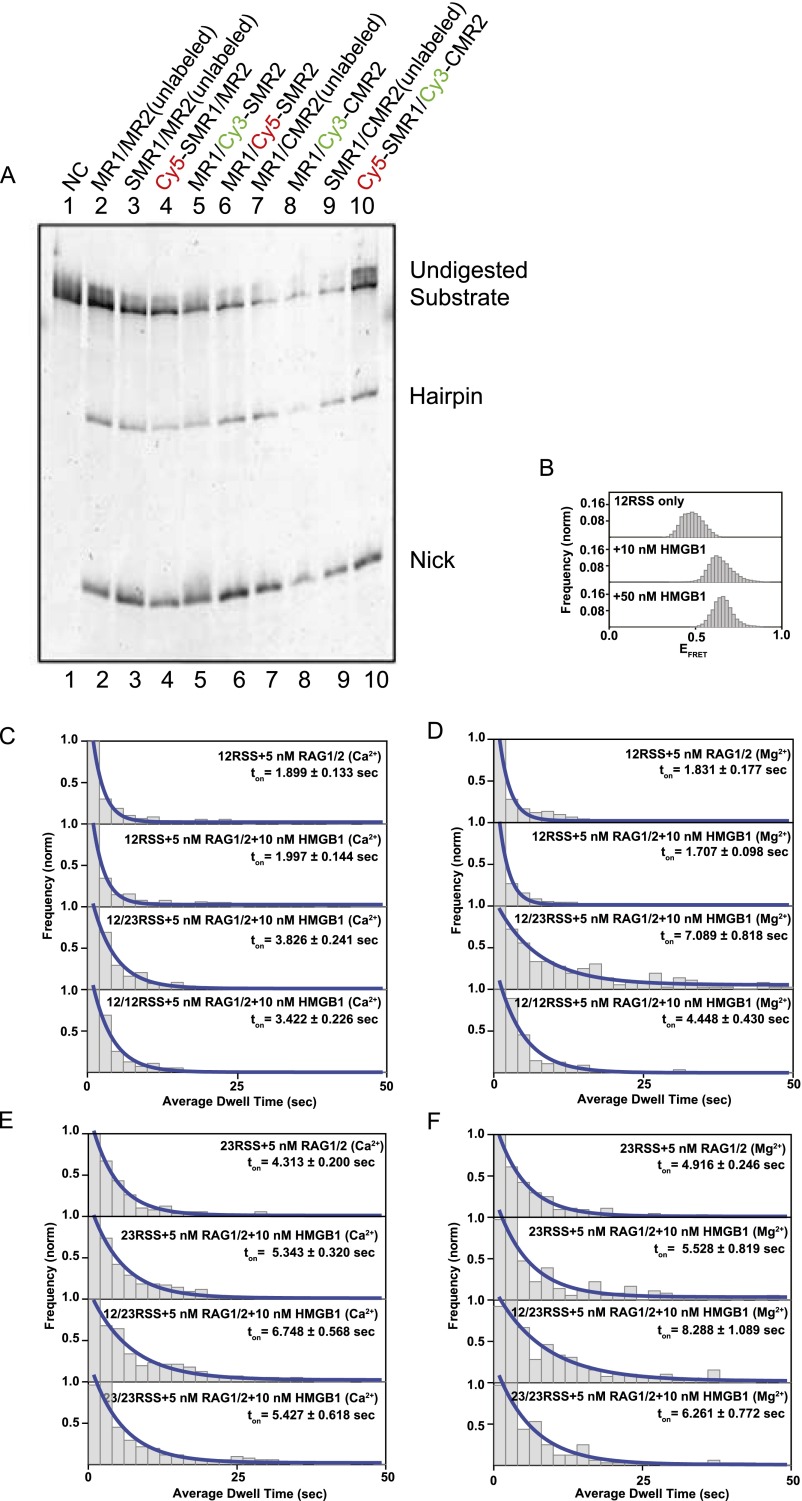

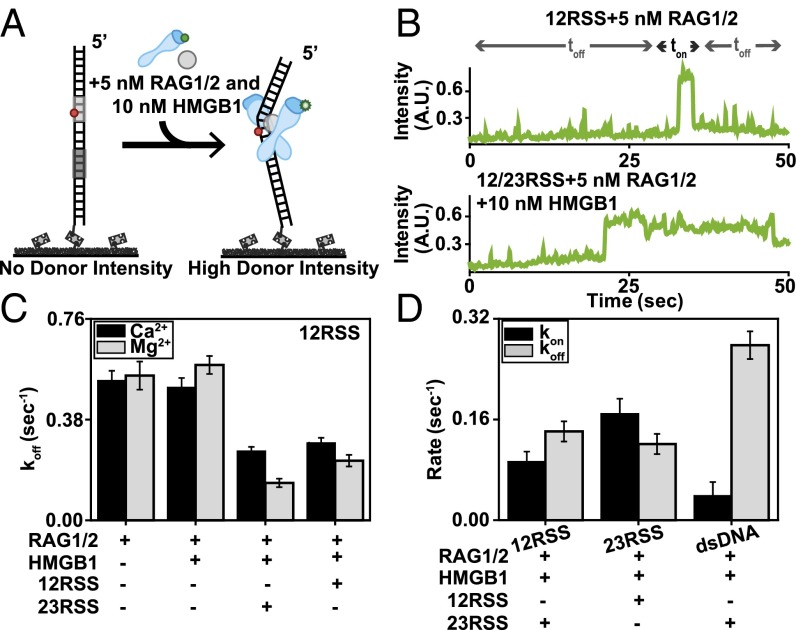

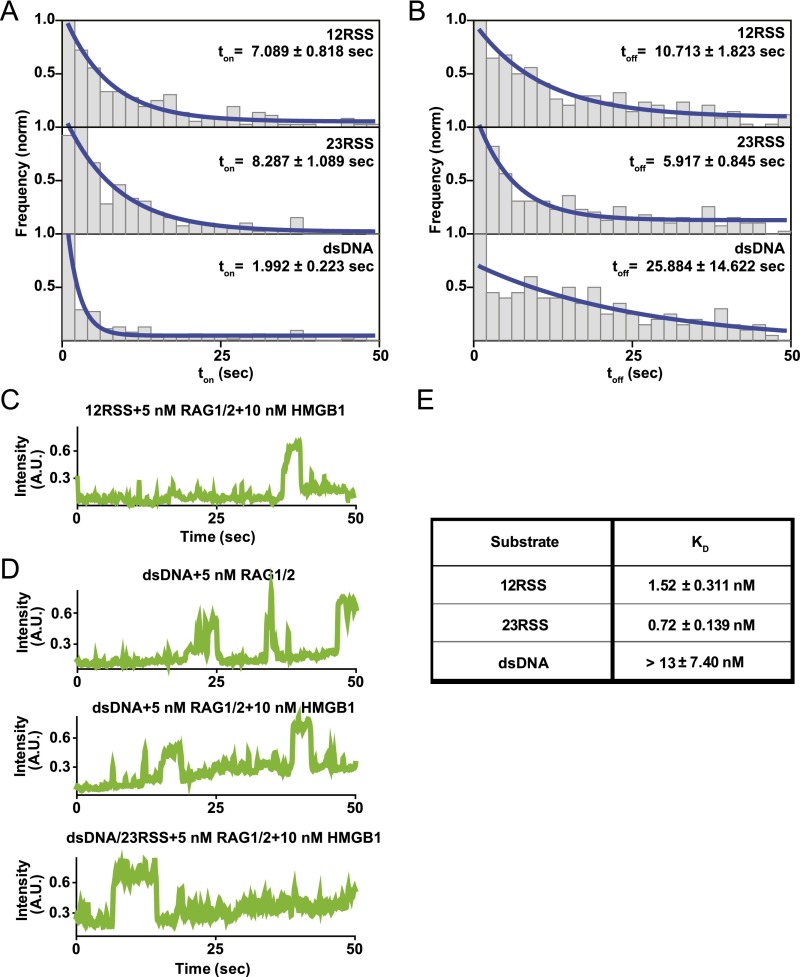

To monitor the kinetics of RAG1/2 binding to DNA substrates in real time, we developed a smCL assay using fluorescently labeled (Alexa Fluor 546) RAG1/2 (Fig. S4A). This enabled us to visualize both the RAG complex and the Cy5-labeled DNA substrate to which it binds (Figs. 3 and 4A). Surface-tethered DNA was labeled with a Cy5 fluorophore marker to confirm that RAG1/2AF546 was binding to RSS substrates and to avoid interference from nonspecific reactions. To prevent background noise due to nonspecific surface binding of RAG1/2AF546, lower concentrations of RAG1/2 and HMGB1 were used. These concentrations were shown to have similar effects on the 12RSS substrate compared with the results of higher concentrations (Fig. S4B). Due to the limited evanescent field of total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy and the diffusion rates of proteins in solution, green intensity was only detected when RAG1/2AF546 interacted with surface-tethered DNA substrates. For these experiments, we monitored fluctuations in green intensity due to RAG1/2AF546 binding events rather than FRET. Fig. 3B and Fig. S5C show representative single-molecule trajectories, each with different proteins in solution, where both binding and dissociation events are observed. Trajectories display an increase in green intensity upon RAG1/2AF546 binding and a drop back to baseline upon dissociation.

Fig. S4.

RAG complex binding assay. (A) Production of the SNAP- or CLIP-tagged RAG protein complex and confirmation of its catalytic activity. Each RAG complex is used in an in vitro cleavage assay with Cy3-labeled 12RSS and unlabeled 23RSS oligonucleotides. The positions of undigested substrate, hairpin product, and nicked product are shown in the margin on the right (C, CLIP tag; CM, CLIP-MBP double tag; M, MBP tag; S, SNAP tag; SM, SNAP-MBP double tag). (B) FRET histograms of the 12RSS substrate (heptamer probe region) showing a similar bending mode for both 10 nM HMGB1 and 50 nM HMGB1. (C–F) Dwell time histograms of RAG1/2AF546 binding to the 12RSS substrate in the presence of Ca2+ (C), the 12RSS substrate in the presence of Mg2+ (D), the 23RSS substrate in the presence of Ca2+ (E), and the 23RSS substrate in the presence of Mg2+ (F). Histograms were generated from a minimum of 75 single-molecule trajectories. Plots were fit with exponential decay curves to extract binding kinetics.

Fig. 3.

Binding kinetics of the RAG complex. (A) Illustration of RAG1/2AF546 smCL assay. Upon RAG1/2 binding, high donor intensity is detected. (B) Representative single-molecule binding trajectories for the 12RSS substrate in the presence of 5 nM RAG1/2, 10 nM HMGB1, and 1 nM 23RSS (Mg2+). Instantaneous increases in intensity indicate RAG1/2AF546 binding events. (C) koff rates for the 12RSS substrate in the presence of RAG complex proteins using the inverse of RAG1/2AF546 dwell time (1/ton). Addition of 10 nM HMGB1 did not substantially change the dwell time for the 12RSS substrate, whereas addition of the 23RSS substrate to the solution decreased koff. (D) kon and koff rates for 12RSS, 23RSS, and dsDNA substrates in the presence of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex and 1 nM RSS (Mg2+).

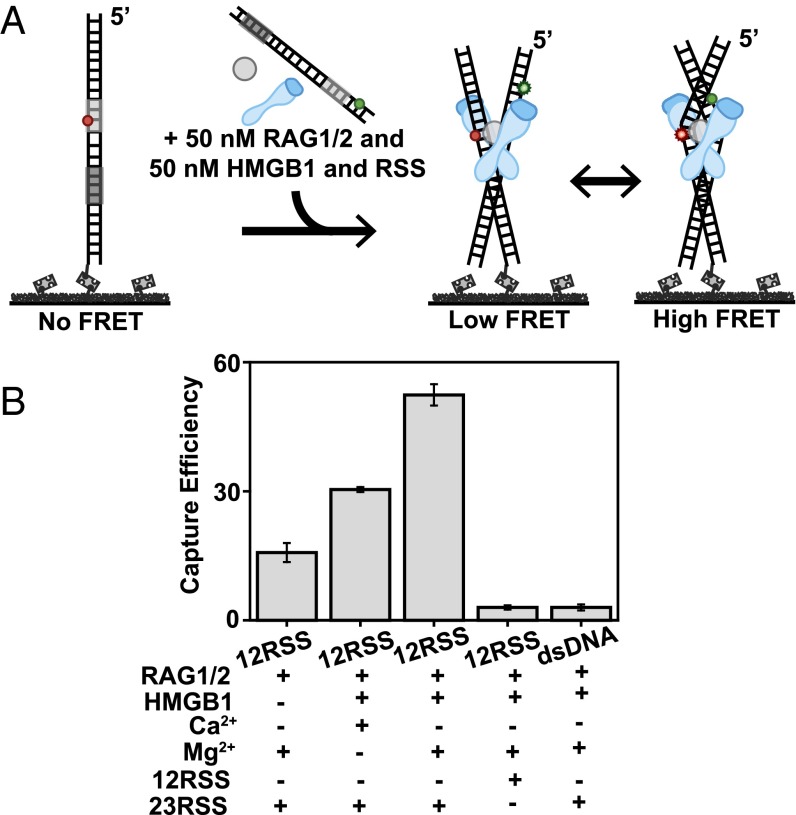

Fig. 4.

Synapsis requirements and visualization of the PC. (A) Illustration of smFRET capture assay for RSS/RSS synapsis. (B) Capture efficiency was measured as the average number of smFRET pairs per imaged area (error bars, s.e.m.; n > 3). The RSS listed directly below the graph represents the RSS tethered to the surface, and those in the subsection represent RSSs in solution.

Fig. S5.

Calculation of koff and kon. (A and B) ton (A) and toff (B) histograms of RAG1/2AF546 for surface-tethered 12RSS, 23RSS, and dsDNA substrates in the presence of 5 nM RAG1/2, 10 nM HMGB1, and 1 nM RSS (Mg2+). Plots were fit with exponential decay curves to extract binding kinetics. koff and kon were generated using the inverse of ton (1/ton) and toff (1/toff), respectively. (C) Representative single-molecule FRET trajectory for the 12RSS substrate in the presence of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex. (D) Representative single-molecule trajectories for dsDNA substrate in the presence of 5 nM RAG1/2, 10 nM HMGB1, and 1 nM 23RSS (Mg2+). Regardless of cofactors in solution, RAG1/2 has minimal interaction with the non-RSS substrate. (E) Calculated KD for 12RSS, 23RSS, and dsDNA substrates.

To derive RAG complex-binding kinetics, we measured the dwell times, ton and toff, in individual trajectories and generated dwell time histograms for 12RSS and 23RSS substrates (Fig. S4 C–F). Histograms were fitted with exponential decay curves, which enabled the determination of kon and koff rates (Fig. 3 D and E). For the 23RSS substrate, there was an increase in RAG1/2 dwell time in the presence of the HMGB1 cofactor (Fig. S5 E and F), which highlights HMGB1’s role in stimulating RAG1/2 binding (5). This may also be reflected in their kinetics where koff transitioned from 0.20 ± 0.01 s−1 for RAG1/2-only conditions to 0.18 ± 0.02 s−1 upon addition of RAG–HMGB1 complex proteins. Reflecting the trend observed in trajectories, there was also a clear increase in dwell time when both 12RSS and 23RSS were included in solution with RAG–HMGB1 complex (Mg2+). This change was more drastic under catalytic conditions than in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. S4C). Overall, a decrease in koff highlighted an increase in RAG1/2 binding stability upon PC formation (Fig. 3C). This increase in stability was observed when either a 12RSS or 23RSS was in solution with the surface-bound 12RSS, implying an attempt at synapsis despite the 12/23 pair rule. From our data, we experimentally determined that the koff of RAG1/2 is 0.14 ± 0.02 s−1 and the kon is 0.09 ± 0.02 nM–1·s−1 (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5 A and B). This provides an experimental KD of 1.52 ± 0.31 nM, which is close to previous kinetic models of RAG1/2 enzyme binding (4.7 ± 0.8 nM) (Fig. S5E) (13). The metrics were also similar to the koff and kon rates measured for synapsis reactions with surface-tethered 23RSS and 12RSS in solution, which yielded the following: koff = 0.12 ± 0.02 s−1 and kon= 0.17 ± 0.02 nM–1·s−1 (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5 A and B). Additionally, RAG1/2 showed high substrate specificity. RAG1/2 had fleeting interactions with dsDNA lacking an RSS with a measured koff of >0.50 ± 0.06 s−1 and kon of 0.04 ± 0.02 nM–1·s−1 (Fig. 3D and Fig. S5D). These are in agreement with previous studies showing that RAG1/2 has a decreased affinity for non-RSS substrates (24).

Visualizing RAG1/2-Mediated RSS Pairing and Synapsis in Real Time.

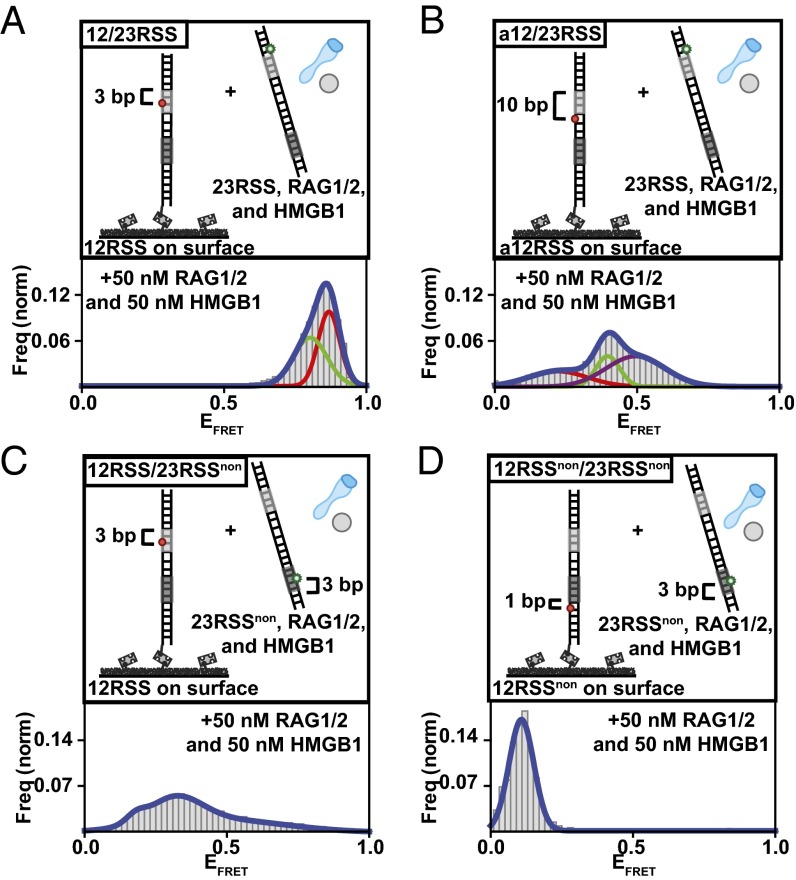

To investigate the requirements for synapsis and to monitor PCs in real time, we established a smFRET capture assay (Fig. 4A). This assay used an acceptor-labeled RSS substrate tethered to the surface and a donor-labeled RSS substrate with RAG complex proteins in solution. Because only donor molecules were being excited, no signal was produced until donor- and acceptor-labeled substrates synapsed. By positioning donor and acceptor molecules near the heptamer region of the synapsed RSS substrates, we were able to visualize the heptamer–heptamer dynamics of the PC. To visualize a substantial number of molecules despite low synapsis efficiency, proteins were incubated for 90 min for all reactions (Fig. S6A). To ensure that the selected molecules exhibited comparable conformational changes at 20-min and 90-min time points, we compared their smFRET histograms. Similar peaks confirmed that we were not visualizing highly stable complexes that were unable to undergo hairpin formation but were rather visualizing highly stable complexes that were very similar populations despite the time difference (Fig. S6 B and C). By quantifying the number of PCs formed on the surface (Fig. S6D), we obtained the efficiency of synapsis as a function of DNA substrate and added proteins. This revealed that both HMGB1 and Mg2+ are important in increasing synapse efficiency (Fig. 4B). Although there was 12/23RSS synapsis in the presence of Ca2+, it occurred with lower efficiency than in the presence of Mg2+. Adding HMGB1 to the solution increased 12/23RSS synapsis by over threefold. Conversely, both dsDNA/23RSS and 12/12RSS reactions led to unsuccessful PC formation, confirming the 12/23 pair rule (25).

Fig. S6.

Synapsis efficiency at earlier time points. (A) Capture efficiency for 12/23RSS and a12/23RSS reactions over time. There are an increased number of molecules detected at the 90-min time point. (B and C) Illustrations of RSS substrates used are located above their respective 20-min and 90-min histograms. 12RSS (B) and a12RSS (C) substrates differ in the location of the acceptor molecule. FRET histograms for both 12RSS and a12RSS had corresponding peaks at both time points, confirming a similar population of molecules despite the time difference. (D) Fluorescence images of individual DNA substrates in synapsis reaction under different conditions, showing their respective donor (green spots) and acceptor (red spots) intensities. The reaction was carried out in the presence of 50 nM RAG1/2 or 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex and allowed a 90-min incubation time. For each reaction, the first listed RSS was tethered to the surface and the second listed RSS is in solution. For example, “12/23RSS” would indicate that 12RSS is tethered while 23RSS is in solution. Both 50 nM HMGB1 and Mg2+ in solution increased the number of PCs. DsDNA acted as a control for nonspecific reactions. (E–G) Representative smFRET trajectories and their histograms for the heptamer–heptamer and 12RSShep/23RSSnon substrates showing dynamic transitions within the PC. The instantaneous drop in FRET signal at the end of the trajectory in E is due to acceptor photobleaching. The trajectories show the following substrates: 12RSShep and 23RSShep (E), a12RSShep and 23RSShep (F), and 12RSShep and 23RSSnon (G).

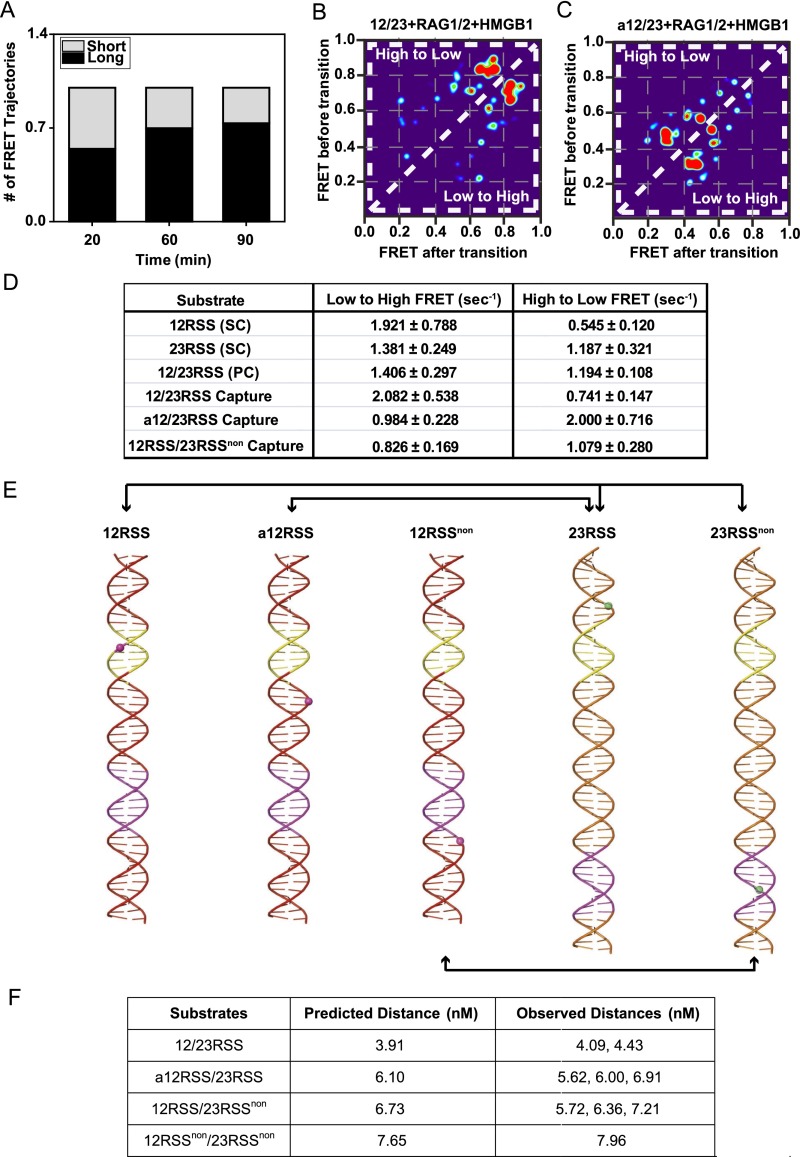

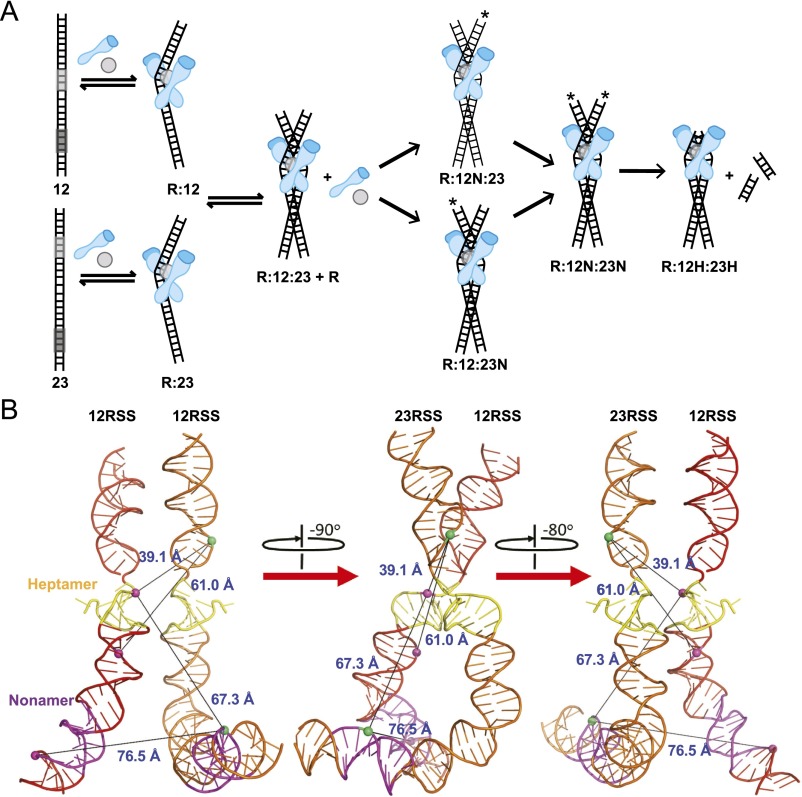

To determine the position and dynamics of the conserved regions within the 12/23RSS PC, we carried out synapsis experiments with 12/23RSS DNA substrates, probing different portions of RSS substrates (Fig. 5 A–D and Fig. S7E). These substrates enabled us to monitor FRET changes between the heptamer–heptamer, nonamer–nonamer, and heptamer–nonamer regions within the paired 12/23RSS complex. The FRET histograms for these substrates revealed substantial high and medium FRET populations for the 12/23RSS heptamer regions (Fig. 5 A and B), indicating a close association between them. The PC also showed distinctive medium–low FRET interaction between the 23RSS nonamer and 12RSS heptamer regions (Fig. 5C), but little to no FRET was observed between nonamer regions (Fig. 5D). We note that these findings are consistent with the recently published PC structure (14) and the coordination of the conserved regions within it (Fig. S7F). The observed FRET populations indicate that PCs retained not a single state but rather multiple conformations. This is evident in the smFRET trajectories of individual 12/23RSS synaptic complexes where transitions between different conformational states in the heptamer–heptamer (Fig. S6 E and F) and nonamer–heptamer (Fig. S6G) regions can be observed. HMM analysis was used to resolve their internal dynamics and extract their transition rates (Fig. S7 B–D). Importantly, the obtained rates are within the range of the bending rates of the conserved regions and likely correspond to the respective bending of the heptamers within the PCs. Despite being a dynamic process, the stability of PCs increased over time. After 20 min, 54% of 12/23RSS complexes displayed FRET behavior for the entire trajectory, and after 90 min, 73% of complexes displayed FRET behavior for the entire trajectory (Fig. S7A). Our data confirm increased stability and decreased dissociation of RSS substrates upon PC formation (13). Taken together, our analysis reveals that the PC is stabilized in a conformation where the heptamer regions are in close association, which would be an optimal configuration for cleavage (Fig. S8).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of the internal organization and conformational dynamics of the PC. (A–D) Illustrations of RSS substrates used are located above their respective histograms. The 12RSS (A) and a12RSS (B) substrates differ in the location of the acceptor molecule. FRET histograms for both 12RSS and a12RSS displayed broad FRET distributions corresponding to multiple FRET states. This indicates internal dynamics within the PC. To emphasize the different states, histograms were fit with multiple-peak Gaussian fits. (C) FRET histogram for 12RSShep and 23RSSnon substrates displayed broad FRET distribution corresponding to multiple intermediate-low FRET states. This indicates that bending of 23RSS brings its nonamer region within FRET distance of the 12RSS heptamer region. (D) Unlike at the heptamer–heptamer and nonamer–heptamer regions, there is little to no FRET between nonamer regions within the PC. A minimum of 75 smFRET trajectories were used to generate each histogram.

Fig. S7.

Internal dynamics of the PC. (A) Stability of PCs formed for the 12/23RSS reaction. Long trajectories displayed FRET behavior for the entire 30-s duration, whereas short trajectories dissociate. PCs show increased stability over time. (B and C) Generated TDP matrices for 12/23RSS and a12/23RSS in the presence of 50 nM RAG–HMGB1 complex (Mg2+). (D) Calculated mean transition rates for the different substrates (error bars, s.e.m.; n > 20 for all measurements). (E) Structural models of the B-form RSS substrates used in capture assays. Heptamer and nonamer regions are shown in yellow and purple, respectively. The phosphates linked to Cy3 and Cy5 are represented as green spheres and magenta spheres, respectively. (F) Comparison of predicted distances based on cryo-EM models with observed distances based on the FRET peaks determined in our experiments.

Fig. S8.

RAG-mediated steps of V(D)J recombination. (A) Integration of structural and catalytic steps of RAG complex binding, bending, and synapsis. Asterisks indicate a nicked RSS substrate. RAG complex reactions occur sequentially: binding, followed by synapsis, followed by nicking and hairpinning catalytic activity. (B) Conformational changes of the 12RSS and 23RSS in the PC based on integration of smFRET with structural data (cryo-EM RAG PC structure; PDB ID code 3JBW). Relative positions of phosphates linked to Cy3 and Cy5 were indicated as green spheres and magenta spheres, respectively. The distance between FRET pairs in tested combinations of substrates is shown. Heptamer regions of the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates are in close association in a stable conformational state, whereas nonamer regions are perpendicular, allowing for FRET between the 23RSS nonamer and 12RSS heptamer.

Discussion

In the work reported here, we used single-molecule assays to define the steps and dynamics of the RAG1/2 reaction mechanism in real time. SmFRET analysis of the RAG complex as it binds to its target (RSS) DNA site revealed that bending occurs at the heptamer, even under noncatalytic conditions (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). This bending is substantial and comparable to conformational changes in the synaptic complex (Fig. S1). Additionally, our assays allowed us to determine HMGB1’s role as a cofactor and how this protein stabilizes RAG1/2-induced bending at the 12RSS heptamer (Fig. 2). HMGB1 also destabilizes RAG1/2-induced bending at the nonamer, highlighting different functionalities of the conserved regions in binding, bending, and catalytic activity (Fig. S3). Using smCL assays, we have derived the DNA binding kinetics of individual RAG1/2–12RSS, –23RSS, and –non-RSS substrates, values that were previously based on inferential assays (Fig. 3). Our data revealed that HMGB1 stimulates RAG1/2 binding to 23RSS and that RAG1/2 dwell time is longer upon synaptic complex formation. We have also derived the kon and koff values of RAG1/2 on dsDNA, showing exceedingly short dwell times and highlighting RAG1/2 substrate specificity. The internal conformational dynamics and architecture of the conserved regions within the synaptic complex were characterized with smFRET capture assays, resolving stable association of the heptamer regions and extreme bending of the 23RSS substrate in the 12/23RSS synaptic complex. These assays also revealed that 12/23RSS synapsis can occur before catalytic activity (i.e., nicking) and that the stability of the synaptic complex increases over time (Figs. 4 and 5). Our results provide an integrated structural and kinetic description of RAG1/2 complex activity and the formation and coordination of the synaptic complex in initiation of V(D)J recombination (SI Discussion).

The effect of RAG1/2 complex binding to RSS DNA was previously addressed using biochemical and biophysical techniques (19, 20, 22, 26) and more recently visualized within the PC in structural analysis (see SI Discussion) (14). These studies indicated that binding of HMGB1 and RAG1/2 induced bending in both the 12RSS and 23RSS DNA substrates as well as in each substrate within the PC. To examine these, we used smFRET analysis and monitored the bending and conformational dynamics of the heptamer and nonamer regions within the RSS substrate. Our measurements revealed that HMGB1 induces persistent bending of DNA substrates that is not RSS sequence-specific, whereas binding of RAG1/2 to DNA substrates results in dynamic bending that is specific for the RSS sequence (Figs. 1 and 2 and Fig. S1). These bending modes were observed around the nonamer and heptamer regions in both the 12RSS and 23RSS substrates (Fig. S3). Additionally, we found that in the presence of HMGB1, RAG1/2-induced transient bending is stabilized at the heptamer but destabilized at the nonamer for the 12RSS substrate (Figs. 1 and 2 and Fig. S3). For the 23RSS substrate, we did not find any change in stabilization by HMGB1 at the heptamer but rather did find an increased RAG1/2 dwell time in the presence of its cofactor. Together our findings demonstrate that the RAG1/2 complex induces dynamic bending within the RSS substrates but with distinctive bending modes exhibited within the 12RSS and 23RSS in the PC.

The DNA substrate specificity of the RAG complex is fundamental to the V(D)J recombination process, uniquely designating the role of RSS regions (5, 6). This specificity, along with the 12/23 rule, has been the subject of several ensemble studies as well as a recent single-molecule study (22). Although these data provided important characteristics of RAG1/2 DNA binding activity, they were mostly derived from inferential assays. Here, we used smCL assays to directly monitor the binding kinetics and substrate specificity of fluorescently labeled RAG1/2 in real time. Our measurements reveal that RAG1/2 binding to RSS is specific and dramatically increases in the presence of both 12RSS and 23RSS and Mg2+ (Fig. 3). The binding kinetics derived from our experiments provide a basis for a description of the progression of the different steps in the recombination process, including RAG1/2-mediated binding, nicking, and synapsis, as recently outlined in molecular models (13). Lower boundaries that were predicted for kon and koff for 12RSS binding (designated a12 and b12, respectively, in supplemental table 1 of ref. 13) are reasonably close to our measured values here. Specifically, their predicted lower boundary is a12 = 1.55 nM–1·min−1 or 0.0258 nM−1·s−1, and our measured kon here is 0.09 ± 0.02 nM–1·s−1. Their predicted lower boundary is b12 = 6.9 min−1 or 0.115 s−1, and our measured koff is 0.14 ± 0.02 s−1. Given the koff and kon values, we conclude that RAG1/2 binds to each RSS substrate sequentially before any catalytic reactions (nicking or hairpinning). Subsequently, RAG1/2 will nick both RSSs in the PC before proceeding to hairpin formation. This kinetic model is illustrated in Fig. S8A.

Beyond the conformation of the RSS substrate and RAG complex binding kinetics, we also determined the efficiency of pairing and the architecture and association of the substrates within the 12/23RSS synaptic complex (Figs. 4 and 5). Consistent with recent cryo-EM studies of the 12/23RSS RAG1/2 synaptic complex (14), our data show a stable and close association between the heptamer regions (Fig. S8B), whereas the nonamer regions are perpendicular (crossed or X conformation), such that the RSS nonamer ends are positioned further away from each other (Fig. S7F). Additionally, the extreme bending (∼120°) of the 23RSS substrate brings its nonamer region within FRET distance of the heptamer region in the 12RSS substrate. The observed bending dynamics of the RSS substrates (Figs. 1 and 2) are also evident within the synaptic complex (Fig. 5), where the rates of FRET transitions measured between opposing heptamer regions are within the range of bending transitions (Fig. S7D). Although the heptamer regions have minor variations in FRET value, the large dynamics at locations farther away from the site of cleavage could be associated with the flexible nonamer-binding domain (NBD) (14, 27).

Overall, the unique single-molecule assays we developed in the course of this work provide a powerful platform for probing RAG1/2-mediated V(D)J recombination. The assays we describe provide a basis for the future determination of the role of RAG complex in disease and how these proteins are modulated by other factors. For example, experiments with RSS-like motifs of cryptic RSSs (cRSSs) and mutated RAG1/2 would offer an opportunity to decipher faulty molecular mechanisms and potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

SI Discussion

Our innovative assays and techniques have allowed us to conclude a number of findings about the RAG complex reaction mechanism. We have concluded that (a) RAG complex binds and bends the RSS at the heptamer; (b) RAG complex bending positions the nonamers at nearly perpendicular orientation even under the dynamic conditions visualized by smFRET (rather than the static crystallography or cryo-EM conditions); (c) RAG binding, bending, and synapsis precede catalysis; and (d) the RAG:12RSS:23RSS synaptic complex assembly is very stable. Our studies also provide single-molecule determination of rate constants that were previously only possible using ensemble (i.e., bulk solution) enzyme kinetics, which can be complicated by inhibition by catalytically inactive RAGs. The matching of our data here with the enzyme kinetic rate constants is not merely confirmatory, given the provisional nature of the rate constants determined by any one method (ensemble enzyme kinetics). Therefore, the fact that the rate constants match is an important fifth finding, in addition to the four points enumerated above. Beyond this, our study adds to the existing knowledge about the assembly and disassembly of the synaptic complex, which was previously only possible via (a) EMSA, (b) kinetic modeling, or (c) particle tethering. Our assays have allowed us to measure specific features of the RAG1/2 pathway that could not be obtained by these other methods (i.e., information about the rates of assembly or disassembly under conditions in free solution), thus providing a sixth finding.

We note that the differences between kinetic constants in our study and another important recent single-molecule study using a different method (tethered particle motion, or TPM) may have several possible explanations (22). One reason could be that although the TPM DNA substrates were over 1 kb long, the minimal length of our substrates (measuring less than 60 nt) would eliminate a large amount of nonspecific reactions. In addition to the substrate length differences, it is important to consider that in our assays 12RSS and 23RSS substrates were not physically linked by intervening DNA, whereas the earlier TPM study had both RSS sites on the same DNA molecule. Additionally, our studies have used truncated HMGB1, whereas the TPM study may have used full-length HMGB1.

As with any scientific method/assay, certain assumptions and limitations exist. Those that apply to the smFRET and smCL techniques used in this study are described as follows:

-

i)

Our measurements provide information about bending, binding, and kinetics, under different experimental conditions (catalytic and noncatalytic). These are proxies for the various steps rather than direct observation of these steps. Therefore, we have relied on the differences between the smFRET for catalytic and noncatalytic conditions (magnesium and calcium divalent conditions, respectively) as the basis for making any inferences about events that occur with or without catalysis. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that future static and dynamic studies of a variety of types will be needed to confirm these inferences.

-

ii)

FRET measurements cannot and do not provide the absolute distance between the donor and acceptor pair, as the FRET factor R0 incorporates additional variables, such as the relative orientation of the fluorophores (18, 36). Consequently, the FRET efficiency provides an estimate of distance rather than an absolute linear distance, as it may also convolve other important changes such as twisting of the DNA double helix. Therefore, distances extracted from FRET data may slightly deviate from those expected from structural models (37).

Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Detailed protein production, purification, and labeling protocols are provided in SI Methods. Murine RAG1 (core region: amino acids 384–1008) or RAG2 (full-length: amino acids 1–527, or core region: amino acids 1–383) vectors were designed as previously described (28). Fluorescently labeled RAG proteins carried a SNAP tag. Proteins were purified as described in ref. 29. Mouse recombinant C-terminal truncated HMGB1 was expressed in bacteria and purified as previously described (30, 31).

SmFRET.

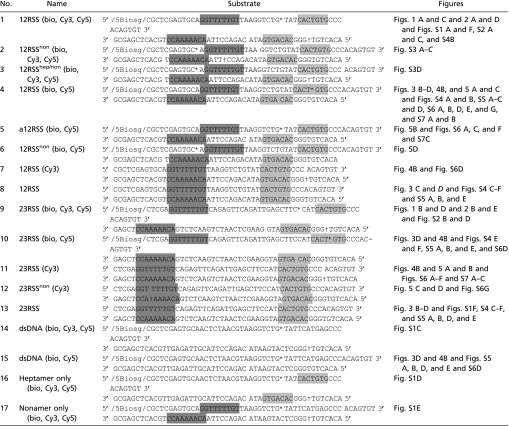

A full description of the DNA preparation and smFRET and smCL assays is provided in SI Methods. All oligonucleotides (Table S1) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology (IDT). SmFRET experiments were carried out as previously described (32, 33).

Table S1.

DNA substrates used in this study

|

*, Cy5 †, Cy3. 5Biosg, biotin; light gray, heptamer region; dark gray, nonamer region.

SI Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

To produce unlabeled RAG1/2, vectors were designed to express murine RAG1 (core region: amino acids 384–1008) or RAG2 (full-length: amino acids 1–527, or core region: amino acids 1–383) that are N-terminally tagged with maltose binding protein (MBP) as previously described (28). To produce fluorescently labeled RAG proteins, the SNAP tag was derived from a pSNAPtag(m) vector (New England Biolabs, cat. no. N9172S) and ligated into pGEM-T Easy. MBP–RAG sequences were derived from existing plasmids, then ligated into pUC19, and the SNAP sequence was then added. The SNAP–MBP–RAG cassette was transferred to a pEBB vector for expression in 293T cells. Proteins were purified using an amylose resin column (New England Biolabs, cat. no. E8021L) as previously described (29). Mouse recombinant C-terminal truncated HMGB1 was expressed in bacteria and purified as previously described (30, 31). SNAP-tagged RAG proteins were fluorescently labeled by incubating overnight at 4 °C with 200 μM SNAP-Surface Alexa Fluor 546 substrate (New England Biolabs, cat. no. S9132S) followed by the isolation of labeled protein using a G25 spin column (Enzymax LLC, cat. no. G25).

DNA Preparation.

To anneal oligonucleotides purchased from IDT (Table S1), appropriate concentrations of oligonucleotides were mixed, heated for 8 min at 94 °C, and then cooled slowly.

SmFRET.

All experiments were carried out at room temperature using a standard buffer composed of 25 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 40 mM NaCl, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and an oxygen scavenging system [1 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.4% (wt/vol) d-glucose, 0.02 mg/mL catalase, and 2 mM Trolox] (38). Buffer also contained either 5 mM MgCl2 (Figs. 1–5 and Figs. S1–S7) or 2.5 mM (Figs. 3 and 4 and Figs. S2, S4, and S6). For all experiments, 50–300 pM DNA was tethered to a PEG-coated quartz surface through biotin–neutravidin linkage. For all experiments, including capture assays, there was no aggregate formation.

Microscopy Set-Up and SmFRET Data Analysis.

We used a custom-built microscopy set-up based on a Leica DMI3000 microscope equipped with a high NA TIRF objective (HCX PL APO; 63×; NA, 1.47; OIL CORR TIRF) followed by achromatic two-tube lens magnification. The microscope was coupled to 532- and 640-nm solid-state lasers to excite the sample at Total-Internal-Reflection illumination mode for improved signal-to-noise ratio and to reject out-of-plane fluorescence. Sample emission was collected and split into two channels through the use of proper dichroic and emission narrow-band bandpass filters (filter for green channel, 580/60; filter for red channel, 680/40; Semrock) in conjunction with the use of a Dual View (DV2-Photometrics) to image two colors simultaneously, side-by-side, onto a single EM-CCD camera (Andor iXon+ 897) acquiring at 33 Hz. For accurate alignment and mapping of the two color channels, we first imaged diffraction-limited fluorescent beads that have wide emission spectra spanning both channels (Invitrogen). The location of the beads was matched for both channels, and a mapping matrix was generated using an Interactive Data Language (IDL) (Exelis Visual Information Solutions) custom mapping routine. Briefly, this routine is based on the use of a polynomial morph-type mapping function, whereby mapping coefficients are generated by Gaussian and centroid fits to the subdiffraction limit point-spread functions of the fluorescence beads. Another IDL code was used, along with the mapping matrix, to extract corresponding single-molecule donor and acceptor spots into single-molecule trajectories. FRET efficiency (EFRET) was estimated as the ratio between the acceptor intensity and the sum of the acceptor and donor intensities. Programs written in Matlab were used to view and analyze FRET trajectories. Normalized histograms were created using over 75 representative molecules. Histograms were generated after subtracting the zero FRET values and truncating photobleached portions of FRET trajectories. HMM analysis and TDPs were done using free software as previously described (32). Briefly, we applied the same unconstrained HMM multistate analysis to all traces, and the resulting transitions were averaged to provide the mean bending/unbending rates rather than specific transition between the different substrates. The resulting two-state transition rates provided an accurate representation of the kinetics in our system and are described in detail in McKinney et al. (23).

Structural Modeling of Measured FRET Values.

All B-form dsDNA helices (substrates 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, and 12) were constructed from the nucleotide sequences used in this experiment by a web server, make-na (structure.usc.edu/make-na/). The figures for RAG structures with bent 12/23RSS were created based on the deposited cryo-EM structure of RAG PC (with NBD, no symmetry) [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 3JBW] (14). The phosphates between nucleotides where Cy3 and Cy5 were linked were shown as green spheres and magenta spheres, respectively. All structures were generated and the distances between those phosphates were measured using PyMOL (39).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1606721113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jung D, Giallourakis C, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW. Mechanism and control of V(D)J recombination at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:541–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumari G, Sen R. Chromatin interactions in the control of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene assembly. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:41–92. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung D, Alt FW. Unraveling V(D)J recombination; insights into gene regulation. Cell. 2004;116(2):299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson PC. Fine structure and activity of discrete RAG-HMG complexes on V(D)J recombination signals. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(5):1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1340-1351.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schatz DG, Swanson PC. V(D)J recombination: Mechanisms of initiation. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: RAG proteins, repair factors, and regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:101–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.150203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JM, Gellert M. Ordered assembly of the V(D)J synaptic complex ensures accurate recombination. EMBO J. 2002;21(15):4162–4171. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swanson PC. A RAG-1/RAG-2 tetramer supports 12/23-regulated synapsis, cleavage, and transposition of V(D)J recombination signals. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(22):7790–7801. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7790-7801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson PC, Kumar S, Raval P. Early steps of V(D)J rearrangement: Insights from biochemical studies of RAG-RSS complexes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;650:1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0296-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ropars V, et al. Structural characterization of filaments formed by human Xrcc4-Cernunnos/XLF complex involved in nonhomologous DNA end-joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(31):12663–12668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100758108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lescale C, et al. RAG2 and XLF/Cernunnos interplay reveals a novel role for the RAG complex in DNA repair. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10529. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy S, et al. XRCC4’s interaction with XLF is required for coding (but not signal) end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(4):1684–1694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Askary A, Shimazaki N, Bayat N, Lieber MR. Modeling of the RAG reaction mechanism. Cell Reports. 2014;7(2):307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ru H, et al. Molecular mechanism of V(D)J recombination from synaptic RAG1-RAG2 complex structures. Cell. 2015;163(5):1138–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim MS, Lapkouski M, Yang W, Gellert M. Crystal structure of the V(D)J recombinase RAG1-RAG2. Nature. 2015;518(7540):507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature14174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornish PV, Ha T. A survey of single-molecule techniques in chemical biology. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2(1):53–61. doi: 10.1021/cb600342a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Giraldo R, et al. Two high-mobility group box domains act together to underwind and kink DNA. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71(Pt 7):1423–1432. doi: 10.1107/S1399004715007452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iqbal A, et al. Orientation dependence in fluorescent energy transfer between Cy3 and Cy5 terminally attached to double-stranded nucleic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(32):11176–11181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801707105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciubotaru M, et al. The architecture of the 12RSS in V(D)J recombination signal and synaptic complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(2):917–931. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciubotaru M, et al. RAG and HMGB1 create a large bend in the 23RSS in the V(D)J recombination synaptic complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(4):2437–2454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas JO, Travers AA. HMG1 and 2, and related ‘architectural’ DNA-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26(3):167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovely GA, Brewster RC, Schatz DG, Baltimore D, Phillips R. Single-molecule analysis of RAG-mediated V(D)J DNA cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(14):E1715–E1723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503477112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKinney SA, Joo C, Ha T. Analysis of single-molecule FRET trajectories using hidden Markov modeling. Biophys J. 2006;91(5):1941–1951. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao S, Gwyn LM, De P, Rodgers KK. A non-sequence-specific DNA binding mode of RAG1 is inhibited by RAG2. J Mol Biol. 2009;387(3):744–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiom K, Gellert M. Assembly of a 12/23 paired signal complex: A critical control point in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell. 1998;1(7):1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciubotaru M, Kriatchko AN, Swanson PC, Bright FV, Schatz DG. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis of recombination signal sequence configuration in the RAG1/2 synaptic complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(13):4745–4758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00177-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin FF, et al. Structure of the RAG1 nonamer binding domain with DNA reveals a dimer that mediates DNA synapsis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(5):499–508. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimazaki N, Tsai AG, Lieber MR. H3K4me3 stimulates the V(D)J RAG complex for both nicking and hairpinning in trans in addition to tethering in cis: Implications for translocations. Mol Cell. 2009;34(5):535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergeron S, Anderson DK, Swanson PC. RAG and HMGB1 proteins: Purification and biochemical analysis of recombination signal complexes. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:511–528. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West RB, Lieber MR. The RAG-HMG1 complex enforces the 12/23 rule of V(D)J recombination specifically at the double-hairpin formation step. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(11):6408–6415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianchi ME, Falciola L, Ferrari S, Lilley DM. The DNA binding site of HMG1 protein is composed of two similar segments (HMG boxes), both of which have counterparts in other eukaryotic regulatory proteins. EMBO J. 1992;11(3):1055–1063. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatterjee S, et al. Mechanistic insight into the interaction of BLM helicase with intra-strand G-quadruplex structures. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5556. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid DA, et al. Organization and dynamics of the nonhomologous end-joining machinery during DNA double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(20):E2575–E2584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420115112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy R, Hohng S, Ha T. A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat Methods. 2008;5(6):507–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman LJ, Gelles J. Mechanism of transcription initiation at an activator-dependent promoter defined by single-molecule observation. Cell. 2012;148(4):679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cisse II, Kim H, Ha T. A rule of seven in Watson-Crick base-pairing of mismatched sequences. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(6):623–627. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothenberg E, Trakselis MA, Bell SD, Ha T. MCM forked substrate specificity involves dynamic interaction with the 5′-tail. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(47):34229–34234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothenberg E, Ha T. Single-molecule FRET analysis of helicase functions. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;587:29–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-355-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]