Significance

In addition to neutralizing antigens, antibodies are also capable of stimulating cellular responses through Fc–Fc receptor interactions. The type of response stimulated by these interactions is influenced by both the Fc receptor type expressed on the effector cell and the isotype of antibody to which it is bound. However, how antibody specificity influences Fc receptor functions, and how antibodies of different specificities interact to modulate these functions, remain unknown. Using influenza A virus as a model, we demonstrate that antibody specificity profoundly influences the induction of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by effector cells. In addition, we show that interactions among antibodies that bind to discrete epitopes on the same antigen can influence the induction of Fc-dependent effector functions.

Keywords: influenza virus, ADCC, antibody, NK cell, Fc receptor

Abstract

The generation of strain-specific neutralizing antibodies against influenza A virus is known to confer potent protection against homologous infections. The majority of these antibodies bind to the hemagglutinin (HA) head domain and function by blocking the receptor binding site, preventing infection of host cells. Recently, elicitation of broadly neutralizing antibodies which target the conserved HA stalk domain has become a promising “universal” influenza virus vaccine strategy. The ability of these antibodies to elicit Fc-dependent effector functions has emerged as an important mechanism through which protection is achieved in vivo. However, the way in which Fc-dependent effector functions are regulated by polyclonal influenza virus-binding antibody mixtures in vivo has never been defined. Here, we demonstrate that interactions among viral glycoprotein-binding antibodies of varying specificities regulate the magnitude of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity induction. We show that the mechanism responsible for this phenotype relies upon competition for binding to HA on the surface of infected cells and virus particles. Nonneutralizing antibodies were poor inducers and did not inhibit antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Interestingly, anti-neuraminidase antibodies weakly induced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and enhanced induction in the presence of HA stalk-binding antibodies in an additive manner. Our data demonstrate that antibody specificity plays an important role in the regulation of ADCC, and that cross-talk among antibodies of varying specificities determines the magnitude of Fc receptor-mediated effector functions.

The discovery and ongoing characterization of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) that bind to the hemagglutinin (HA) stalk domain of influenza A viruses (IAVs) has galvanized promising new efforts to generate a universal influenza virus vaccine (1). A number of studies have now firmly established that stalk-specific bnAbs, normally present in low quantities, can be boosted substantially in humans following exposure to HA subtypes with antigenically foreign head domains (2–8). Sequential vaccination of animals with chimeric HAs or with “headless” vaccine constructs have effectively recapitulated the boosting of bnAbs observed in humans after exposure to foreign HAs, and also are protective against heterologous and heterosubtypic IAV challenge (9–15). These strategies are now being tested as promising “universal” influenza virus vaccine candidates (16).

Whereas traditional strain-specific antibodies neutralize virus by inhibiting receptor binding, stalk-binding bnAbs neutralize virus by distinct postbinding mechanisms (17). A direct comparison of in vitro neutralization has revealed that strain-specific mAbs that inhibit receptor binding tend to be more potent at neutralizing virus compared with monoclonal stalk-binding bnAbs (18, 19); however, this difference is minimized in the context of a polyclonal response (18). In addition to virus neutralization, recent work by DiLillo et al. (20) has demonstrated that HA stalk-binding antibodies are potent inducers of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), and that this property is essential for optimal protection in vivo. These authors also reported that strain-specific HAI+ antibodies, which bind to the head domain of HA, do not elicit ADCC (20). Although these studies were performed by passive transfer of well-defined mAbs, they nonetheless suggest that the specificity of antibodies (and thus the epitope that they bind) may play a critical role in determining their effector functions.

Whereas the differential ability of antibody isotypes to mediate Fc effector responses is determined by their relative affinities for activating and inhibitory Fc receptors, how antibody specificity (i.e., the particular epitope to which an antibody binds) affects Fc-dependent effector functions has not been studied. Given that almost all antibody responses in humans are polyclonal, we sought to define how specificity might regulate ADCC in the context of IAV infection. Using a combination of human and mouse mAbs, as well as polyclonal human IgG, we demonstrate that only bnAbs that bind to the HA stalk domain potently elicit ADCC. Classical head domain-binding antibodies that exhibit hemagglutination-inhibiting (HAI) activity did not strongly induce ADCC and, moreover, negatively regulated ADCC induction by stalk-binding bnAbs. Inhibition of ADCC by HAI+ antibodies is likely the result of competition for binding to HA in the context of infected cells or virus particles. This competition depends on both the relative affinity of each antibody and the accessibility of the epitope to which it binds. Interestingly, nonneutralizing HA-binding antibodies were not capable of potently eliciting ADCC on their own, despite being of the appropriate isotype. These antibodies also had no effect on the ability of HA stalk-binding bnAbs to induce ADCC. In contrast, neuraminidase (NA)-binding antibodies could weakly induce ADCC, and also could cooperate with HA stalk-binding bnAbs.

Taken together, the foregoing findings demonstrate that antibody specificity plays a critically important role in the regulation of Fc-dependent effector functions such as ADCC. Because induction of ADCC is known to play an important role in the protection against many viruses, including IAV and HIV (21, 22), as well as in cancer immunotherapies (23), it will be important to consider the effects not only of antibody isotype, but also of specificity in the development of both novel vaccines and therapeutics.

Results

HAI+ Antibodies Inhibit Induction of ADCC by bnAbs That Bind to the HA Stalk Domain.

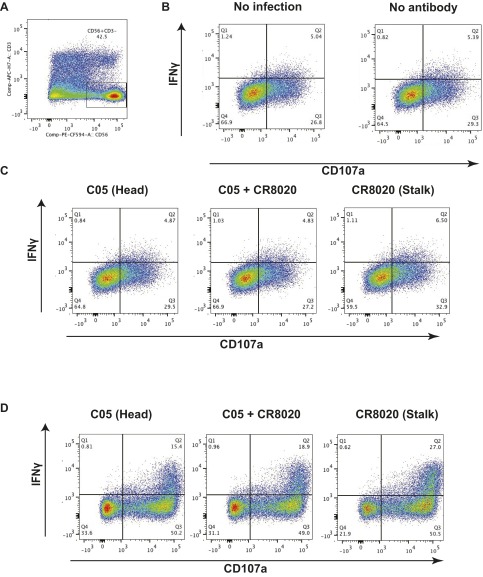

Because monoclonal bnAbs that bind to the HA stalk domain have been reported to potently induce ADCC, whereas mAbs to the HA head domain do not, we sought to investigate how ADCC would be regulated in the context of a polyclonal response, to better recapitulate in vivo conditions (20). To test this, we first made use of primary human natural killer (NK) cells freshly isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors. NK cells were incubated with target cells expressing HK/68 H3 and stained for the classical ADCC activation markers CD107a and IFNγ (Fig. S1D). As expected, the HAI+ antibody C05 induced only weak ADCC activation relative to the HA stalk-binding bnAb CR8020. However, mixing of CR8020 and C05 at equal concentrations resulted in inhibition of ADCC relative to CR8020 alone (Fig. 1 A and B). The same phenomenon occurred when NK cells grown in continuous culture with artificial antigen-presenting cells were incubated with identical antibodies on target cells infected with X-31 virus (H3N2) (Fig. 1 C and D and Fig. S1 A–C). These results suggest that HAI+ antibodies are capable of inhibiting ADCC induced by HA stalk-binding bnAbs on infected cells and cells expressing exogenous HA only.

Fig. S1.

Primary NK cell ADCC assay. (A) Primary human NK cells were grown in continuous culture on K562 cells. Gates were set on the CD56+CD3- subset (NK cells) for downstream analysis. (B) IFNγ and CD107a expression was monitored on uninfected A549 target cells and on infected A549 cells not treated with antibody. (C) On incubation of infected target cells with C05, CR8020, or C05 and CR8020, NK cell activation was assessed by measuring IFNγ and CD107a expression. (D) Primary NK cells freshly isolated from PBMCs using a CD56+ selection kit were incubated with 293T cells expressing HK/68 H3. Cells were incubated with C05, CR8020, or C05 and CR8020. NK cell activation was assessed by measuring the IFNγ and CD107a expression.

Fig. 1.

HAI+ antibodies inhibit induction of ADCC by bnAbs that bind to the HA stalk domain. (A and B) The ADCC assay was performed using primary NK cells. ADCC was measured as a percentage of activation above HK/68 H3-expressing target cells without antibody. The data shown represent the mean of technical replicates from each independent donor. (C and D) ADCC activation of NK cells grown in continuous culture was also assessed after incubation on infected A549 target cells incubated with the indicated antibodies. Data represent the mean and SEM of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. (E–G) ADCC reporter assays were performed on X-31 (H3N2) cells (E and G) and on Cal/09-infected A549 cells (F) using combinations of murine mAbs (E and F) or human mAbs (G). The mean and SEM values for biological experiments performed in triplicate are shown.

To study the relationship between antibody specificity and ADCC induction using a more reductionist and high-throughput system, we made use of a well-validated, commercially available ADCC assay in which A549 cells are infected with IAV and express HA on the cell surface in its natural context. After antibodies were added to the HA-expressing cells, a luciferase reporter cell line expressing murine FcγRIV was added to wells to allow for the quantification of ADCC induction. Cells infected with IAV strain X-31 (H3N2) were incubated with the murine HA stalk-binding bnAb 9H10 (IgG2a) (24) or the H3 head domain neutralizing antibody XY102 (IgG2a) (25) at concentrations ranging from 0.0008 to 5 µg/mL. As expected, 9H10 potently induced ADCC, whereas XY102 did not.

Surprisingly, when the concentration of 9H10 was held constant at 5 µg/mL and XY102 was titrated into the system, ADCC was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1E). To ensure that this phenomenon was not subtype-specific, we repeated the experiment by infecting cells with A/California/04/09 (Cal/09) H1N1, followed by incubation with the H1 stalk-binding bnAb 6F12 (IgG2b) or the Cal/09-specific head domain neutralizing antibody 7B2 (IgG2a). Consistent with our previous results, 6F12 potently induced ADCC, whereas 7B2 failed to activate the reporter cell line; however, when the two antibodies were mixed, 7B2 antagonized ADCC induction by 6F12 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1F).

To confirm that our findings are indeed relevant in the context of human IAV infection, we repeated the aforementioned experiments using human antibodies and a reporter cell line expressing human FcγRIIIa. This served the dual purpose of ensuring that our observations were not artifacts of the murine FcγRIV cell line or of hybridoma-derived antibodies. CR8020 (IgG1) is a human H3 stalk-binding bnAb, whereas C05 binds to the H3 head domain and displays classical HAI activity (26, 27). Both were produced by recombinant expression in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK 293T) cells. In agreement with our earlier results, CR8020 potently stimulated ADCC, and this activity could be blocked with increasing concentrations of C05. This antagonism specifically required C05 binding, given that a nonbinding IgG1 isotype control antibody failed to inhibit ADCC activation (Fig. 1G). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the induction of ADCC is regulated by the relative ratio of neutralizing antibodies that bind to the HA head domain and exhibit classical HAI activity to bnAbs that bind to the stalk domain of HA.

Nonneutralizing Antibodies Against HA Neither Potently Induce nor Inhibit ADCC.

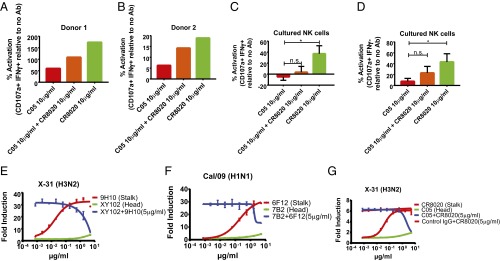

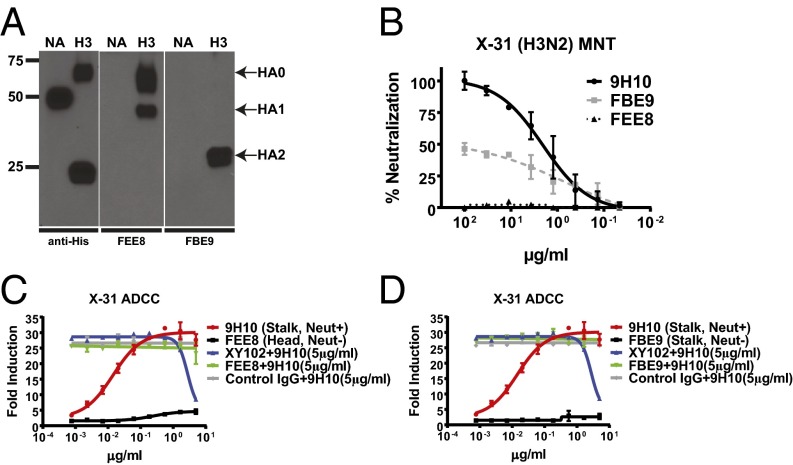

In addition to neutralizing antibodies that bind to the HA head and stalk or to NA, numerous cross-reactive antibodies are produced during infection or vaccination that are capable of binding to HA or NA but lack neutralization activity in vitro (6). Because these antibodies are plentiful in individuals who have been previously exposed to IAV, it was important to assess whether they too might modulate ADCC induction. FEE8 (IgG2a) is a murine nonneutralizing antibody that binds to the HA1 domain (most of which comprises the HA head) of A/Hong Kong/1/1968 (HK/68) H3, whereas FBE9 (IgG1) is a nonneutralizing antibody that binds to the stalk domain (Fig. 2 A and B). On its own, FEE8 was unable to stimulate ADCC, recapitulating the phenotype observed with neutralizing antibodies that bind to the HA head domain. However, unlike neutralizing antibodies, FEE8 did not inhibit ADCC induction when mixed with the HA stalk-binding bnAb 9H10 (Fig. 2C). Because it is a murine IgG1 antibody, FBE9 cannot stimulate ADCC on its own; however, like FEE8, it did not inhibit the induction of ADCC by the bnAb 9H10 (Fig. 2D). Thus, only HA stalk-binding bnAbs are capable of robustly inducing ADCC, and this activity can be antagonized by HA head-binding antibodies that exhibit classical HAI activity.

Fig. 2.

Nonneutralizing HA-binding antibodies neither induce nor inhibit ADCC induced by HA stalk-binding bnAbs. (A) Western blot analysis was performed against 293T cells transfected with plasmids expressing His-tagged HK/68 H3 or N2 (negative control) using anti-His, FEE8, or FBE9. (B) The neutralization activities of 9H10, FEE8, and FBE9 were tested against X-31 by a microneutralization assay on MDCK cells. (C and D) The ability of FEE8 (Neut−, HA head-binding) and (C) FBE9 (Neut−, HA stalk-binding) (D) to induce ADCC or inhibit ADCC induced by 9H10 was evaluated on X-31–infected A549 cells. Because these assays were performed in parallel, the curves for 9H10, XY102 + 9H10, and control IgG + 9H10 are duplicated in C and D for clarity and ease of comparison. Data represent the mean and SEM values of biological experiments performed in triplicate.

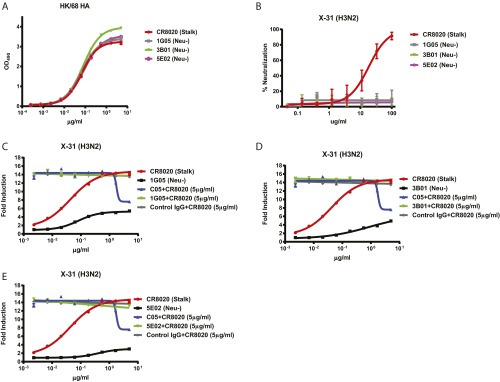

Both FEE8 and FBE9 bound to HA with substantially lower affinity compared with 9H10 (Table S1). Therefore, to determine whether the lack of potent ADCC induction by nonneutralizing antibodies is related to affinity, we analyzed three additional human nonneutralizing antibodies―1G05 (stalk-binding), 3B01 (stalk-binding), and 5E02 (head-binding)―that bound to HA with affinity equivalent to the human stalk-binding bnAb CR8020 (Fig. S2A), yet did not neutralize virus in vitro (Fig. S2B). These antibodies were capable of only modest ADCC induction and did not affect the induction of ADCC by CR8020 (Fig. S2 C–E).

Table S1.

Affinity measurements of mAbs

|

Fig. S2.

Lack of potent ADCC induction by nonneutralizing antibodies is independent of affinity. (A) ELISAs were performed using recombinant HK/68 H3 HA to compare the binding affinities of CR8020, 1G05, 3B01, and 5E02. (B) The neutralization activities of CR8020, 1G05, 3B01, and 5E02 were measured against X-31 by a microneutralization assay on MDCK cells. (C–E) In vitro ADCC assays were performed on X-31–infected A549 cells using the human HA stalk-binding bnAb CR8020 either alone or in combination with human nonneutralizing mAb 1G05 (C), 3B01 (D), or 5E02 (E). Because the experiments were performed in parallel, the curves for CR8020, C05 + CR8020, and control IgG + CR8020 are shown in triplicate in C, D, and E for clarity and ease of comparison. Data represent the mean and SEM of biological experiments run in triplicate.

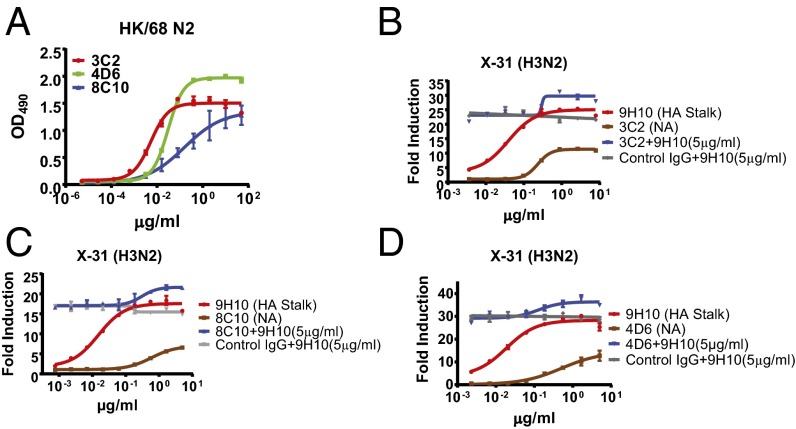

NA-Inhibiting Antibodies Cooperate with HA Stalk-Binding bnAbs to Enhance Induction of ADCC in an Additive Manner.

In addition to HA, a substantial antibody response is also generated against the second major IAV surface glycoprotein, NA. Although present in substantially lower quantities than HA-binding antibodies, NA-binding antibodies can inhibit NA activity, which has been shown to confer protection from infection in vivo (28–30). Certain HA-binding antibodies have been shown to exhibit NA-inhibiting (NAI) activity through steric hindrance of the NA enzymatic site (28). Therefore, we examined whether NA-binding antibodies by themselves could induce ADCC or influence ADCC induced by HA stalk-binding bnAbs. We studied three NAI+ mAbs: 3C2, 8C10, and 4D6 (all IgG2a) (Fig. 3A). Alone, these antibodies were capable of only modest ADCC induction; however, when combined with the bnAb 9H10, these NAI+ antibodies exhibited cooperative activity and enhanced induction of ADCC in an additive manner (Fig. 3 B–D). These data demonstrate that although NAI+ antibodies do not potently induce ADCC on their own, they are capable of enhancing bnAb-mediated ADCC.

Fig. 3.

NAI+ antibodies are capable of cooperating with HA stalk-binding bnAbs to boost ADCC induction. (A) ELISAs were performed using recombinant HK/68 N2 protein to test the binding affinities of 3C2, 4D6, and 8C10. (B–D) In vitro ADCC assays were performed on X-31–infected A549 cells using the HA stalk-binding antibody 9H10 either alone or in combination with the NAI+ antibodies 3C2 (B), 8C10 (C), or 4D6 (D). Data represent the mean and SEM values of biological experiments performed in triplicate.

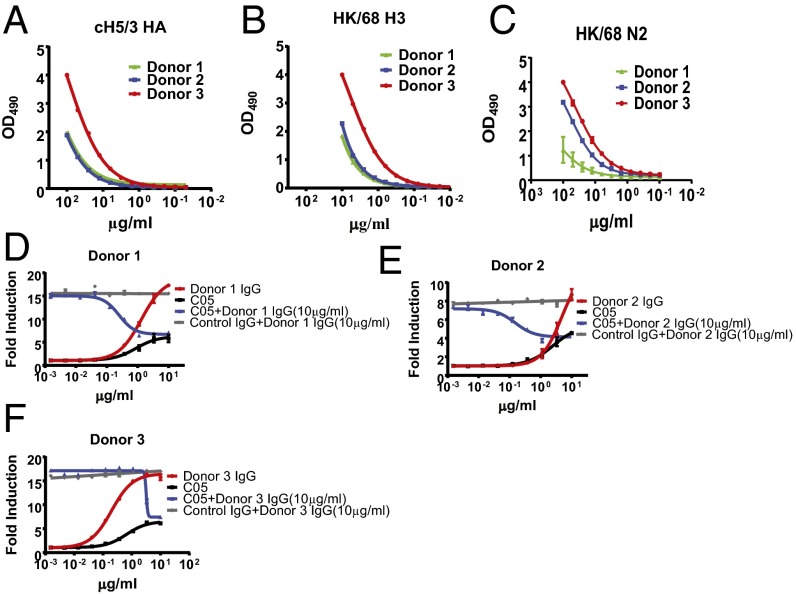

Induction of ADCC by Human Polyclonal IgG Is Influenced by the Ratio of ADCC-Inducing and -Inhibiting Antibodies.

The foregoing results clearly demonstrate that antibody specificity (i.e., the HA epitope to which a particular antibody binds) profoundly influences both the ability to induce ADCC and the induction of ADCC by antibodies of other specificities in a polyclonal response. Thus, we turned our attention to investigating whether our model would hold true in the natural context of human polyclonal serum. To do this, we purified polyclonal IgG from the serum of three healthy adult donors (Table S2), and assessed the ability of these antibodies to induce ADCC in X-31–infected cells. We first performed ELISAs to quantify the extent of H3 stalk-binding antibodies using recombinant cH5/3 HA (Fig. 4A), total HK/68 HA-binding antibodies (Fig. 4B), and total HK/68 NA-binding antibodies (Fig. 4C), as described previously (2, 3, 18). As expected, IgG antibodies from each donor were capable of inducing ADCC when added to the infected monolayer. Notably, antibodies purified from donor 3, who had the strongest cH5/3 reactivity (which specifically measures stalk-binding antibodies) and the strongest NA reactivity, also most potently induced ADCC (compare Fig. 4 A–C and F). Consistent with our earlier results, the extent of ADCC induction was influenced by the proportion of ADCC-activating antibodies (stalk and NA binding) and ADCC-inhibiting antibodies, given that spiking the polyclonal IgG samples with C05 (HAI+) could inhibit ADCC induction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 D–F). Thus, during infection of influenza-exposed humans, the extent of ADCC induction seems to be regulated by the relative proportion of ADCC- activating and ADCC-inhibiting antibodies. Owing to the complex nature of antibody specificities in polyclonal mixtures, it is possible that other species of ADCC-activating and -inhibiting antibodies (i.e., ADCC-inhibiting antibodies that bind to NA) may exist that influence the magnitude of response observed for each donor.

Table S2.

Donor information

|

Fig. 4.

The induction of ADCC by antibodies in human polyclonal serum is regulated by the relative proportion of ADCC activating and inhibiting antibodies. Polyclonal IgG was purified from the serum of human donors over protein G-Sepharose columns. (A) Quantities of H3 stalk-binding antibodies were determined by ELISA against recombinant cH5/3 HA. (B and C) Quantities of total HA-binding antibodies (B) and N2-binding antibodies (C) were determined by ELISA against recombinant HK/68 HA or NA. (D–F) In vitro ADCC assays were performed on X-31–infected A549 cells using polyclonal IgG isolated from healthy adult donors either alone or in combination with the HAI+ human mAb antibody C05. (D) Donor 1. (E) Donor 2. (F) Donor 3. Data represent the mean and SEM values of biological experiments performed in triplicate.

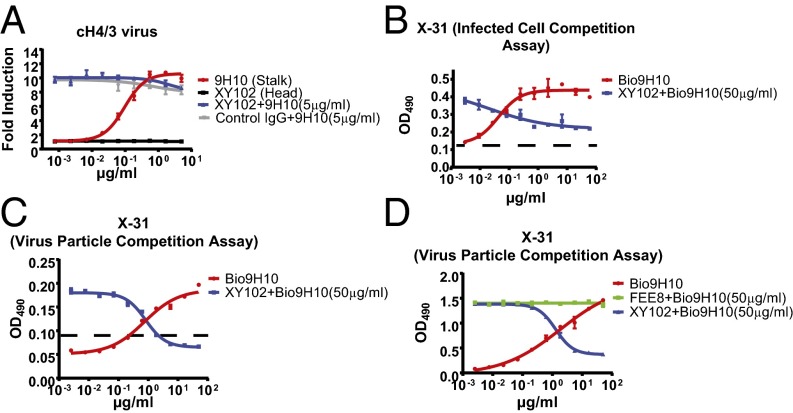

ADCC Inhibition by HAI+ Antibodies Is Achieved Through Competitive Binding to HA on Virus Particles and on the Surface of Infected Cells.

We next sought to define the mechanism responsible for HAI+ antibody-mediated inhibition of ADCC induced by HA stalk domain-binding bnAbs. To establish whether binding of HAI+ antibodies to HA was required for their inhibitory activity, we performed an ADCC assay on cells infected with a recombinant A/Puerto/Rico/8/1934 (PR8) virus expressing a chimeric 4/3 HA protein (cH4/3). This protein contains the stalk domain of A/Perth/16/2009 H3 and the head domain of an H4 avian virus. As expected, the HA stalk-binding bnAb 9H10 was capable of inducing ADCC in a dose-dependent manner. However, XY102, which is specific for the H3 head domain of A/Hong Kong/1/1968 (HK/68) and thus unable to bind to cH4/3 HA, lost its ability to inhibit ADCC activation (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

ADCC inhibition by HAI+ antibodies is mediated by competition for binding HA on the surface of infected cells and virus particles. (A) In vitro ADCC assays were performed on cH4/3 virus-infected A549 cells using XY102 (HAI+), 9H10 (stalk-binding bnAb), or combinations thereof. (B and C) ELISA-based binding competition assays were performed on X-31–infected A549 cells (B) or on purified X-31 (C) using XY102 (HAI+), biotinylated 9H10 (HA stalk-binding bnAb), or both. The limit of detection of these assays is shown as a dashed line (background + 3 SD). (D) Another binding competition assay was performed on purified X-31 using biotinylated 9H10 and FEE8 (HAI−, head-binding). Data represent the mean and SEM values of biological experiments performed in triplicate.

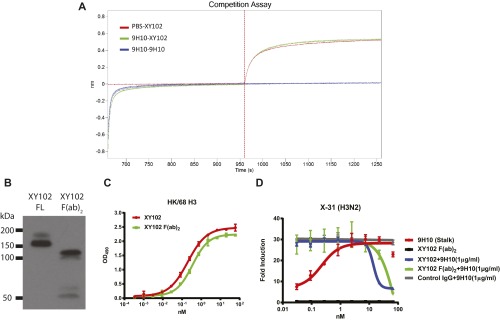

Because binding of XY102 was clearly required to mediate inhibition of ADCC by 9H10, we then examined the possibility that XY102 might interfere with 9H10 binding to HA. To do this, we first performed a competitive binding assay using biolayer interferometry. Recombinant HK/68 H3 was immobilized on probes, and binding to XY102 alone, to 9H10 followed by XY102, or to 9H10 followed by 9H10 again (as a positive control for competition), was measured. As expected, XY102 alone bound to the probe efficiently. Furthermore, 9H10 and XY102 were able to bind to the probe at the same time without any interference/competition (Fig. S3A).

Fig. S3.

The Fc region of the HAI+ antibody is not required for blocking of the ADCC mediated by HA stalk-binding bnAbs. (A) Binding of 9H10, XY102, or both was assayed by biolayer interferometry against immobilized recombinant HK/68 H3 protein. (B) Western blot analysis was performed to test the purity of XY102 F(ab)2 using anti-murine F(ab)2 antibody. (C) ELISAs were performed using recombinant HK/68 H3 to compare the binding affinities of XY102 IgG and XY102 F(ab)2. XY102 IgG and XY102 F(ab)2 were tested at equal molarity. (D) In vitro ADCC assays were performed on X-31–infected A549 cells using XY102, XY102 F(ab)2, 9H10, or combinations thereof. XY102 IgG and XY102 F(ab)2 were tested at equal molarity. Data represent the mean and SEM of biological experiments run in triplicate.

Despite the fact that no competition in binding to immobilized recombinant HA was observed between 9H10 and XY102, we recognized that this does not accurately recapitulate the natural arrangement of HA on the surface of infected cells. Thus, we also performed ELISA-based binding competition assays against HA on the surface of infected cells, in the same context in which it is found naturally. (This is also the context in which our ADCC assays were performed.) Indeed, when the assay was performed under these conditions, XY102 was able to outcompete 9H10 for binding to HA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). The same phenotype could be recapitulated by assessing competition using purified virus particles (Fig. 5C). If competition for binding to HA can explain the ADCC inhibition observed previously, then it stands to reason that antibodies that are unable to inhibit ADCC also should not compete with HA stalk-binding bnAbs.

Consistent with this line of reasoning, we observed no competition for binding to purified virus particles between the nonneutralizing antibody FEE8 and 9H10 (Fig. 5D). Thus, direct competition for binding to HA expressed on virus particles and the surface of infected cells is sufficient to explain the inhibition of stalk antibody-mediated ADCC by HAI+ antibodies. This competition is influenced by both antibody affinity and epitope accessibility (Fig. S3 and SI Results).

SI Results

Antibody Affinity and Epitope Accessibility Influence Competition-Mediated ADCC Inhibition.

To better understand the role of binding affinity in influencing ADCC inhibition, we performed biolayer interferometry to measure the binding affinities of the murine mAbs used in this study against recombinant HK/68 HA (the HA expressed by X-31) (Table S1). Interestingly, the stalk-binding bnAb 9H10 exhibited the strongest binding affinity (Kd = 2.14e−11 M), whereas the HAI+ head-binding antibody XY102 had a Kd of 3.73e−10 M. Each of the nonneutralizing antibodies had considerably lower affinities (Table S1). The ability of XY102 to outcompete 9H10 despite having lower affinity likely can be attributed to the relatively greater accessibility of the head domain compared with the stalk.

To determine whether the Fc region of HAI+ antibodies was required for inhibition of bnAb-mediated ADCC, we generated F(ab)2 fragments from XY102 (Fig. S3B). Binding of the XY102 F(ab)2 was unchanged (Fig. S3C), and indeed F(ab)2 fragment was able to inhibit ADCC induced by 9H10 (Fig. S3D). Therefore, the ability of HAI+ head-binding antibodies to inhibit ADCC induction by HA stalk-binding bnAbs by competition for HA binding is influenced by the relative affinity of the two antibodies, but is independent of the Fc region of the inhibiting antibody.

Discussion

Owing to the exquisite neutralization potency exhibited by HAI+ IAV strain-specific antibodies, the role of Fc-dependent effector functions in contributing to protection from homologous infection is thought to be negligible (20). However, extensive work by the Ravetch, Kent, and Ennis laboratories has demonstrated that cross-reactive antibodies are capable of eliciting ADCC against nonhomologous IAVs, and that the induction of ADCC by these antibodies might contribute to protection in vivo (22, 31–37). Furthermore, work by DiLillo et al. (20) has demonstrated that ADCC induction by HA stalk-binding bnAbs is required for optimal protection on a lethal challenge of mice that received a passive transfer of a monoclonal HA stalk-binding bnAb.

The most prominent targets of ADCC-inducing antibodies are the two major surface glycoproteins of IAV, HA and NA. Whereas the ability of different antibody isotypes to mediate downstream Fc-effector functions has been well established, how antibody specificity affects the induction of FcR-dependent mechanisms like ADCC has not been addressed. We therefore systematically characterized multiple antibody specificities that bind to the IAV surface glycoproteins for their ability to induce ADCC and for ADCC-modifying interactions among antibodies of distinct specificities (Fig. S4). Although we have limited our studies to ADCC specifically, these findings are likely to extend to other FcR-dependent mechanisms as well, such as antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP).

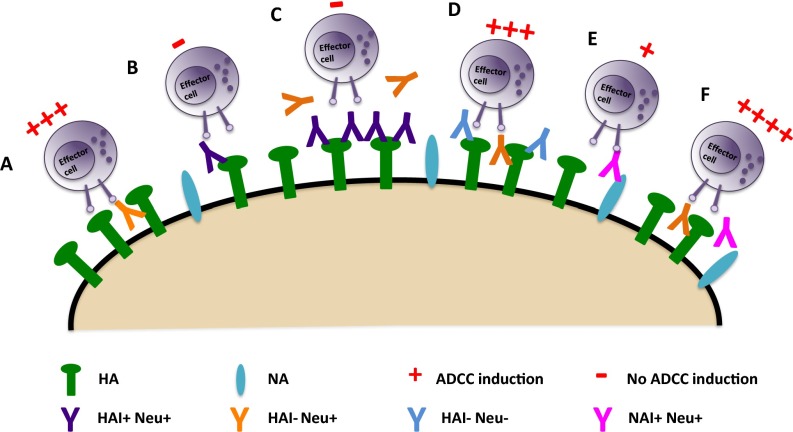

Fig. S4.

Model of ADCC activation by IAV-specific antibody specificity. (A and B) HA stalk-binding bnAbs potently stimulate the activation of ADCC (A), whereas HAI+ antibodies that bind to the HA head domain do not (B). (C) However, HAI+ antibodies are able to inhibit ADCC induction by stalk-binding bnAbs through direct competition for binding to HA on the surface of viral particles and infected cells. (D) HA-reactive nonneutralizing antibodies do not inhibit ADCC mediated by HA stalk-binding bnAbs. (E) NAI+ antibodies do not potently activate ADCC on their own. (F) However, they can cooperate with HA stalk-binding bnAbs to boost ADCC induction.

Consistent with previous studies, we found that HA stalk-binding bnAbs were able to potently induce ADCC, whereas HAI+ antibodies were not (20). Nonneutralizing antibodies directed against HA were not capable of potent ADCC induction, despite being of the appropriate isotype (IgG2a). Nevertheless, these antibodies have been reported to have the capability to protect from lethal infection in vivo (37, 38). Interestingly, NAI+ antibodies induced ADCC weakly on their own, and cooperated with HA stalk-binding bnAbs to enhance ADCC induction. These results are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that some NA-specific mAbs are capable of protecting against influenza virus challenge in vivo, albeit at much higher concentrations than for HA stalk-binding bnAbs (37). This firmly demonstrates that antibody specificity plays a critical role in the stimulation of Fc-dependent effector functions like ADCC.

The reason why bnAbs targeting the HA stalk domain seem to be the most potent activators of ADCC in the context of IAV infection remains elusive. The fact that HAI+ antibodies do not elicit ADCC suggests that binding of HA to the sialic acid residues on the surface of effector cells may potentiate ADCC. These dual interactions might increase receptor clustering or the strength and/or duration of the interaction between target cells and effector cells. This also would explain why NAI+ antibodies cooperate with HA stalk-binding bnAbs, because binding of the antibodies to NA inhibits their enzymatic activity. This model does not explain why nonneutralizing HA-specific antibodies fail to induce ADCC, however. It has been suggested that in vivo antibodies have unique glycoforms that potentiate activating Fc–Fc receptor interactions (39, 40). It is also possible that binding to the HA stalk domain alters the conformation of the Fc region in a way that promotes the Fc receptor binding and/or clustering required for ADCC activation. Given the requirement for Fc receptor clustering to achieve optimal downstream signaling, it is possible that the relatively weak ADCC induced by NAI+ antibodies is related to the relatively sparse expression of NA relative to HA on the surface of virus particles and infected cells, which may not be sufficient to promote downstream signaling (41).

Importantly, we found that antibodies with discrete specificities have the ability to cross-talk to regulate ADCC induction. Here we report that HAI+ antibodies are capable of inhibiting ADCC induction by HA stalk-binding bnAbs in a concentration-dependent manner. This has important consequences not only for IAV, but also in many natural scenarios in which ADCC might occur in the context of a polyclonal antibody response. In the case of IAV specifically, these observations imply that when sufficient quantities of HAI+-neutralizing antibodies are present, ADCC is inhibited, and neutralization functions as the primary mode of protection. This scenario would most likely occur in the context of reexposure to a homologous IAV strain, after either infection or vaccination. However, when HAI+ antibodies are absent or limiting, bnAbs targeting the HA stalk domain engage effector cells to stimulate ADCC and thereby limit the spread of infection. This is likely to be the primary mechanism through which a “universal” IAV vaccine would confer protection. Thus, it is encouraging that we also observed no inhibition of ADCC by cross-reactive, nonneutralizing antibodies, which are likely to be present in most preexposed individuals.

The ability of HAI+ antibodies to inhibit HA stalk antibody-mediated ADCC on both virus particles and on the surface of infected cells suggests that other Fc-dependent effector functions, such as ADCP and antibody-mediated complement-dependent cell lysis, also may be regulated by interactions among antibodies of differing specificities. Indeed, the signaling pathways that regulate these processes are largely conserved (42). Given that in the case of IAV, the inhibition of ADCC relies on competition for binding to HA, both affinity and epitope accessibility play roles in determining the eventual outcome. Despite having lower affinity than 9H10, XY102 is capable of competing for binding, because the HA head domain on virus particles and on the surface of infected cells is substantially more accessible than the HA stalk domain. These data are consistent with recent studies showing that poor accessibility of the stalk domain is partly responsible for the relatively low quantities of HA stalk-specific antibodies produced under normal conditions (43).

Taken together, our findings identify a previously unappreciated role for antibody specificity in regulating Fc-dependent effector functions such as ADCC. We also demonstrate that interactions among antibodies of unique specificities in polyclonal mixtures can modulate the extent of Fc receptor activation. These findings should be carefully considered in the design of novel vaccines and therapeutics in which induction of Fc-dependent effector functions are important for achieving efficacy, including those targeting HIV and cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses.

Adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial cells (A549; American Type Culture Collection) and Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (HyClone) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). X-31 and cH4/3 viruses are reassortant viruses that have six internal proteins of PR8. X-31 viruses express the HA and NA of HK/68 H3N2. cH4/3 viruses express chimeric cH4/3 HA (H4 globular head domain from A/duck/Czechoslovakia/1956 and H3 stalk domain from A/Perth/16/2009) and N1 of PR8 virus.

IgG F(ab)2 Preparation.

XY102 F(ab)2 antibody fragments were created using the F(ab′)2 Preparation kit (Pierce). XY102 IgG was digested by immobilized pepsin at acidic pH. Then the digested product was passed through an immobilized NAb Protein A Plus Spin Column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to separate undigested IgG. Flowthrough was collected and dialyzed against PBS using Amicon Ultra centrifugal 50-kDa filter units (Millipore) to separate small peptides of the Fc portion. The final product was XY102 F(ab)2.

ELISA.

ELISA was performed as described previously (18).

Microneutralization Assays.

Microneutralization assays were performed as described previously (19).

Biolayer Interferometry.

For binding competition assays, biotinylated recombinant HA proteins (20 µg/mL) were immobilized onto streptavidin-coated biosensors (ForteBio) for 5 min. After the baseline signal was measured in kinetics buffer for 3 min, biosensor tips were immersed into the wells containing primary antibody at a concentration of 50 µg/mL for 5 min. Biosensors then were immersed into wells containing competing mAbs at a concentration of 50 µg/mL for 5 min. The values of y-axes were recorded in real time.

For Kd determination, purified mAbs were loaded onto AMC (anti-mIgG Fc capture) biosensors (ForteBio) in kinetics buffer for 180 s. For the measurement of kon, the association was measured for 180 s by exposing the sensors to seven concentrations of purified HA of HK/68 in 1× kinetics buffer. For the measurement of koff, the dissociation was measured for 180 s in 1× kinetics buffer. Experiments were performed at 30 °C. Kd values were calculated according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Primary NK Cell ADCC Assay.

NK cells were either purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cellsd (PBMCs) isolated from peripheral blood using Lymphoprep density gradient medium (Stem Cell Technologies), followed by a CD56+ magnetic selection kit (Stem Cell Technologies), or were isolated from peripheral blood and put into continuous culture with K562 cells (clone 9) at a 1:2 ratio in RPMI supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 1 mM HEPES, 1 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, and 100 ng/mL IL-2 (Peprotech) every 2–3 d, as reported previously (44). As targets, HEK 293T cells were transfected with a HK/68 HA plasmid or A549 cells were infected with X-31 (H3N2) for 18 h to allow for HA expression. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were incubated with antibodies for 1 h. Antibodies were then removed, and 4 × 105 CD56+ cells were added to the transfected cells along with anti-human CD107a-APC (H4A3; BD Biosciences). After 1 h of incubation, 5 µg/mL brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) and Golgistop (BD Biosciences) were added following the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by incubation for another 5 h. Cells were then washed and stained extracellularly with anti-human CD56-PECF594 (NCAM-16.2) and anti-human CD3-APCH7 (SK7; BD Biosciences). Cells were washed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm and then stained intracellularly with anti-human IFNγ-BV421 (4S.B3; BD Biosciences). All samples were run on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo 10.0.6 (TreeStar). All experiments using primary human cells were approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board. All donors provided informed consent.

ADCC Reporter Assay.

A549 cells were seeded on 96-well white flat-bottom plates. At 24 h later, cells were infected with influenza viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3. On the day of assay, the medium was replaced with assay buffer (RPMI 1640 with 4% (vol/vol) low IgG FBS), followed by the addition of serial dilutions of antibodies. The infected cells were incubated together with antibodies at 37 °C for 30 min. Jurkat effector cells (Promega) were resuspended in assay buffer and then added to assay plates at a concentration of 7.5 × 104 cells per well. After incubation at 37 °C for 6 h, Bio-Glo Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) was added, and luminescence was quantified using a Synergy 4 plate reader (Bio-Tek).

Infected Cell-Based Competition Assay.

A549 cells were infected with influenza viruses at an MOI of 3 on the day before the assay. At 16 h later, the cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 3% BSA. A mixture of biotinylated (EZ-link Micro NHS-PEG4-Biotinylation Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) stalk and unlabeled head antibodies were added to the cells, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were washed with PBST. Secondary HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Millipore) was added at 1:5,000 dilution for 1 h. After the addition of HRP substrate (Sigmafast OPD; Sigma-Aldrich), reactions were stopped by the addition of 3 M HCl, and the optical densities were read at 490 nm on a Synergy 4 plate reader (Bio-Tek).

Virus Particle-Based Competition Assay.

The 96-well plates were coated with 2 µg/mL sucrose gradient-purified X-31 virus particles overnight in bicarbonate-carbonate coating buffer (100 mM, pH 9.6). All other steps were performed as described above.

SI Materials and Methods

Antibodies.

XY102 (1), 9H10 (2), 6F12 and 7B2 (3), C05 (4), CR8020 (5), 1G05, 3B01, and 5E02 (6) have been described previously. 3C2, 8C10, and 4D6 hybridomas were generated using a previously described protocol (2). FEE8 and FBE9 hybridomas were produced by sequential infection of 6- to 8-wk-old female BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories) with a sublethal dose of HK/68 H3N2, A/Victoria/361/2011 H3N2, and rPhil/82 (HA and NA of A/Philippines/2/82; the remaining segments from PR8 viruses) over 3-wk intervals. The mice were killed at 3 d after the last infection. Spleens were harvested and dissociated into single-cell suspensions in serum-free DMEM. Fusion of splenocytes and SP2/0 myeloma cells was performed using polyethylene glycol (Sigma-Aldrich). Fused cells were grown for 10–12 d, and cell colonies were picked and grown for screening.

Supernatants were collected from hybridoma cultures and filtered before IgG purification. IgG antibodies were purified using a gravity flow column containing protein G-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). The supernatants were passed through the column once, and the resins were washed with PBS. The antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine HCl (pH 2.7), and the eluate was quickly neutralized with 2 M Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 10). Antibodies were concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (Millipore) with a 30-kDa molecular mass cutoff.

ELISA.

In brief, plates were coated with 2 µg/mL purified recombinant HK/68 HA or cH5/3 HA (H5 head domain of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 and H3 stalk domain of A/Perth/16/2009) overnight in bicarbonate-carbonate coating buffer (100 mM, pH 9.6). On the day of the assay, the plates were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk for 1 h. Antibodies were diluted in 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk and then incubated on plates for 1 h. The plates were washed three times with PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). Secondary sheep anti-mouse IgG-HRP (GE Healthcare) was incubated on plates at 1:5,000 dilution in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. Before the addition of HRP substrate (Sigmafast OPD; Sigma-Aldrich), the plates were washed extensively with PBST. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 3 M HCl, and the optical densities were read at 490 nm on a Synergy 4 plate reader (Bio-Tek).

Microneutralization Assays.

In brief, mAbs and viruses (1,000 pfu/50 µL) were preincubated for 30 min at room temperature before inoculation of confluent MDCK cells in 96-well plates. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h at 5% CO2 to allow for adsorption. After washing with PBS, the plates were reincubated with infection medium containing equivalent concentrations of diluted antibody supplemented with 1 µg/mL TPCK-trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 20 h, the cells were fixed with 80% acetone and then stained for NP to quantify virus replication.

Polyclonal IgG Purification.

Polyclonal IgG was purified from human serum as described previously (7). In brief, human serum was heat-inactivated by incubation at 56 °C for 30 min and then diluted 1:4 in PBS for filtration through a 0.22-µm-pore filter unit. The filtered serum was then applied to a gravity flow column (Qiagen) containing protein G-Sepharose resin (InvivoGen) to purify IgG. After the serum was passed over the column three times, the resins were washed with five column volumes of PBS. IgG was eluted using 0.1 M glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.7) and then quickly neutralized in 2 M Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 10). Purified IgG was concentrated and dialyzed against PBS using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (Millipore) with a 30-kDa molecular mass cutoff.

Western Blot Analysis.

The 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing H3 HA or N2 NA of HK/68. Cell lysates were collected 16 h later and then boiled for 5 min at 100 °C in loading buffer containing SDS and 0.6 M DTT. SDS migration buffer was used for electrophoresis. Samples were separated on 4–20% SDS/PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were then blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk for 1 h and incubated with either a monoclonal anti-His antibody (H3 HA and N2 NA are His-tagged), FEE8, or FBE9 overnight. After three washes with PBST, the blots were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and then developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ariana Hirsch for technical assistance and Sea Lane Biotechnologies for the kind gift of C05. Funding for this work was provided in part by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant (to M.S.M.), the Center for Research on Influenza Pathogenesis, a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–funded Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance [Contract HHSN272201400008C (PI, Adolfo Garcia-Sastre)] (to P.P. and F.K.), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grants P01-AI097092 (to P.P.), and U19-AI109946 (to P.P. and F.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.R.B. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1609316113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Krammer F, Palese P. Advances in the development of influenza virus vaccines. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(3):167–182. doi: 10.1038/nrd4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller MS, et al. 1976 and 2009 H1N1 influenza virus vaccines boost anti-hemagglutinin stalk antibodies in humans. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(1):98–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller MS, et al. Neutralizing antibodies against previously encountered influenza virus strains increase over time: A longitudinal analysis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(198):198ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellebedy AH, et al. Induction of broadly cross-reactive antibody responses to the influenza HA stem region following H5N1 vaccination in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(36):13133–13138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414070111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G-M, et al. Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(23):9047–9052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118979109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wrammert J, et al. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2011;208(1):181–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halliley JL, et al. High-affinity H7 head and stalk domain-specific antibody responses to an inactivated influenza H7N7 vaccine after priming with live attenuated influenza vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(8):1270–1278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pica N, et al. Hemagglutinin stalk antibodies elicited by the 2009 pandemic influenza virus as a mechanism for the extinction of seasonal H1N1 viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(7):2573–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200039109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krammer F, et al. H3 stalk-based chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus constructs protect mice from H7N9 challenge. J Virol. 2014;88(4):2340–2343. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03183-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Tan GS, Palese P. Hemagglutinin stalk-reactive antibodies are boosted following sequential infection with seasonal and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in mice. J Virol. 2012;86(19):10302–10307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01336-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krammer F, et al. Assessment of influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based immunity in ferrets. J Virol. 2014;88(6):3432–3442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03004-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel J, et al. Influenza virus vaccine based on the conserved hemagglutinin stalk domain. MBio. 2010;1(1):e00018-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00018-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wohlbold TJ, et al. Vaccination with soluble headless hemagglutinin protects mice from challenge with divergent influenza viruses. Vaccine. 2015;33(29):3314–3321. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yassine HM, et al. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat Med. 2015;21(9):1065–1070. doi: 10.1038/nm.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Impagliazzo A, et al. A stable trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem as a broadly protective immunogen. Science. 2015;349(6254):1301–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krammer F, Palese P. Universal influenza virus vaccines: Need for clinical trials. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(1):3–5. doi: 10.1038/ni.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandenburg B, et al. Mechanisms of hemagglutinin targeted influenza virus neutralization. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He W, et al. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza virus antibodies: Enhancement of neutralizing potency in polyclonal mixtures and IgA backbones. J Virol. 2015;89(7):3610–3618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03099-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He W, Mullarkey CE, Miller MS. Measuring the neutralization potency of influenza A virus hemagglutinin stalk/stem-binding antibodies in polyclonal preparations by microneutralization assay. Methods. 2015;90:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):143–151. doi: 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramski M, Stratov I, Kent SJ. The role of HIV-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in HIV prevention and the influence of the HIV-1 Vpu protein. AIDS. 2015;29(2):137–144. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jegaskanda S, Reading PC, Kent SJ. Influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity: Toward a universal influenza vaccine. J Immunol. 2014;193(2):469–475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiLillo DJ, Ravetch JV. Differential Fc-receptor engagement drives an anti-tumor vaccinal effect. Cell. 2015;161(5):1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan GS, et al. Characterization of a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody that targets the fusion domain of group 2 influenza A virus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 2014;88(23):13580–13592. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02289-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moran TM, et al. Characterization of variable-region genes and shared cross-reactive idiotypes of antibodies specific for antigens of various influenza viruses. Viral Immunol. 1987;1(1):1–12. doi: 10.1089/vim.1987.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekiert DC, et al. Cross-neutralization of influenza A viruses mediated by a single antibody loop. Nature. 2012;489(7417):526–532. doi: 10.1038/nature11414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekiert DC, et al. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science. 2011;333(6044):843–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1204839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wohlbold TJ, et al. Hemagglutinin stalk- and neuraminidase-specific monoclonal antibodies protect against lethal H10N8 influenza virus infection in mice. J Virol. 2015;90(2):851–861. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02275-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wohlbold TJ, et al. Vaccination with adjuvanted recombinant neuraminidase induces broad heterologous, but not heterosubtypic, cross-protection against influenza virus infection in mice. MBio. 2015;6(2):e02556. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02556-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monto AS, et al. Antibody to influenza virus neuraminidase: An independent correlate of protection. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(8):1191–1199. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jegaskanda S, et al. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in intravenous immunoglobulin as a potential therapeutic against emerging influenza viruses. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(11):1811–1822. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jegaskanda S, et al. Age-associated cross-reactive antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity toward 2009 pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(7):1051–1061. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jegaskanda S, Weinfurter JT, Friedrich TC, Kent SJ. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity is associated with control of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection of macaques. J Virol. 2013;87(10):5512–5522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03030-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jegaskanda S, et al. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies in the absence of neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol. 2013;190(4):1837–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Co MDT, et al. Relationship of preexisting influenza hemagglutination inhibition, complement-dependent lytic, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies to the development of clinical illness in a prospective study of A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in children. Viral Immunol. 2014;27(8):375–382. doi: 10.1089/vim.2014.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terajima M, Co MDT, Cruz J, Ennis FA. High antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibody titers to H5N1 and H7N9 avian influenza A viruses in healthy US adults and older children. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(7):1052–1060. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiLillo DJ, Palese P, Wilson PC, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(2):605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI84428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henry Dunand CJ, et al. Both neutralizing and non-neutralizing human H7N9 influenza vaccine-induced monoclonal antibodies confer protection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(6):800–813. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang TT, et al. Anti-HA glycoforms drive B cell affinity selection and determine influenza vaccine efficacy. Cell. 2015;162(1):160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pincetic A, et al. Type I and type II Fc receptors regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(8):707–716. doi: 10.1038/ni.2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palese P, Shaw M. Orthomyxoviridae: The viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, et al., editors. Fields Virology. 5th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1647–1690. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrews SF, et al. Immune history profoundly affects broadly protective B cell responses to influenza. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(316):316ra192–316ra192. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denman CJ, et al. Membrane-bound IL-21 promotes sustained ex vivo proliferation of human natural killer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]