Abstract

Purpose

The practice of medicine is shifting from a paternalistic doctor-patient relationship to a model in which the doctor and patient collaborate to decide optimal treatment. This study aims to determine if the older orthopedic population desires a shared decision making (SDM) approach to their care and to identify patient predictors for the preferred type of approach.

Methods

This cross-sectional investigation enrolled 99 patients with a minimum age of 65 years, at a tertiary hand specialty practice between March and June 2015. All patients completed the Control Preferences Scale (CPS), a validated system that distinguishes between patient preferences for patient-directed, collaborative, or physician-directed decision-making. Bivariate and logistic regression analyses assessed associations between demographic data, clinic encounter variables such as familiarity with provider, trauma, diagnosis, and treatment decision, and the primary outcome of CPS preferences.

Results

Eighty one percent of patients analyzed preferred a more patient-directed role in decision making, with 46% of the total cohort citing a collaborative approach as their most preferred treatment approach. Sixty-seven percent cited the most physician-directed approach as their least preferred model of decision-making. Forty-nine percent reported that spending more time with their physician to address questions and explain the diagnosis would be most useful when making a health care decision and 73% preferred additional written informational material. Familiarity with the provider was associated with being more likely to prefer a collaborative approach.

Conclusions

Older adult patients with symptomatic upper extremity conditions desire more patient-directed roles in treatment decision making. Given the limited amount of reliable information independently obtained outside the office visit, our data suggest that written decision aids offer an approach to shared decision making that is most consistent with the preferences of the older orthopedic patient.

Clinical Relevance

This study quantifies older adults’ desire to participate in decision making when choosing among treatments for hand conditions.

Keywords: control preferences scale, elderly, hand, older, shared decision-making

INTRODUCTION

The doctor-patient relationship is evolving. The traditional paternalistic interaction in which the doctor dictates treatment is fading as patient populations have sought to become more actively involved in determining the course of their medical care.1,2 This change is likely multifactorial and linked to shifting societal values, increased access to medical information, and healthcare providers realizing that patients often want to participate in healthcare decisions.3 Proposed shared decision making (SDM) models offer a distinct way to practice that may improve patient satisfaction, decrease patient-physician decision conflict, and improve the likelihood that patients pursue the intervention that best aligns with their personal values and goals.4

SDM relies on unbiased education of patients regarding their disease, available treatment options, and the risks and benefits of each option. SDM requires a patient to clarify their values and goals. To this end, decision aids (DA) exist in a variety of mediums including paper handouts, information videos, and interactive computer programs.5 Decision aids, with strict development and validation criteria, are distinct from pamphlets explaining what a single recommended treatment entails.6

SDM has only recently been investigated in orthopedic surgery.7 In clinic visits where patients faced the decision between operative and non-operative treatment for joint arthritis, SDM improved patients’ confidence in their decisions and decreased time to decision-making.8 Within the field of hand and upper extremity surgery, recent data has indicated discordance between surgeon and patient preferences in decision-making for trigger finger and carpal tunnel syndrome9,10. In non-traumatic conditions with an elective operative option and in traumatic conditions without a consensus optimal treatment, patient preference and values ought to be a priority.9

As the population ages, the number of older adult patients seeking treatment for electively-treated conditions such as osteoarthritis or traumatic conditions without a consensus optimal treatment, such as distal radius fractures, will continue to rise. The United States has a rapidly aging population—by 2030 there will be 75 million people >65 years old, more than double the number in 2000.11 Current data on this population’s desire to engage in a more patient-directed role in healthcare decision-making remains conflicting.2,3,12–15 This study aimed to determine the preferred decision-making role among older adult patients seeking upper extremity specialty care. Secondarily, we sought to determine if a patient’s preferred decision-making role varied according to patient demographics, health literacy, or diagnosis type. We tested the null hypotheses that this patient population would prefer the traditional physician-directed role in decision-making and that no demographic or clinical variables would impact the desired level of participation in their care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This institutional review board-approved, cross-sectional, observational investigation enrolled 99 patients to assess their desired level of participation in medical decision-making and the factors influencing that choice. All patients presented to one of six orthopedic hand surgeons at a tertiary hand practice from March 2015 through June 2015. Eligible patients were English-speaking, ≥65 years of age, and able to complete surveys with minimal assistance. Patients were excluded if they were not fluent in English or had any mental comorbid condition (n=2) that impaired their ability to consent or participate in medical decision-making. Each enrolled patient completed study-related measures a single time at their first appointment within the study timeframe.

Measurement Tools

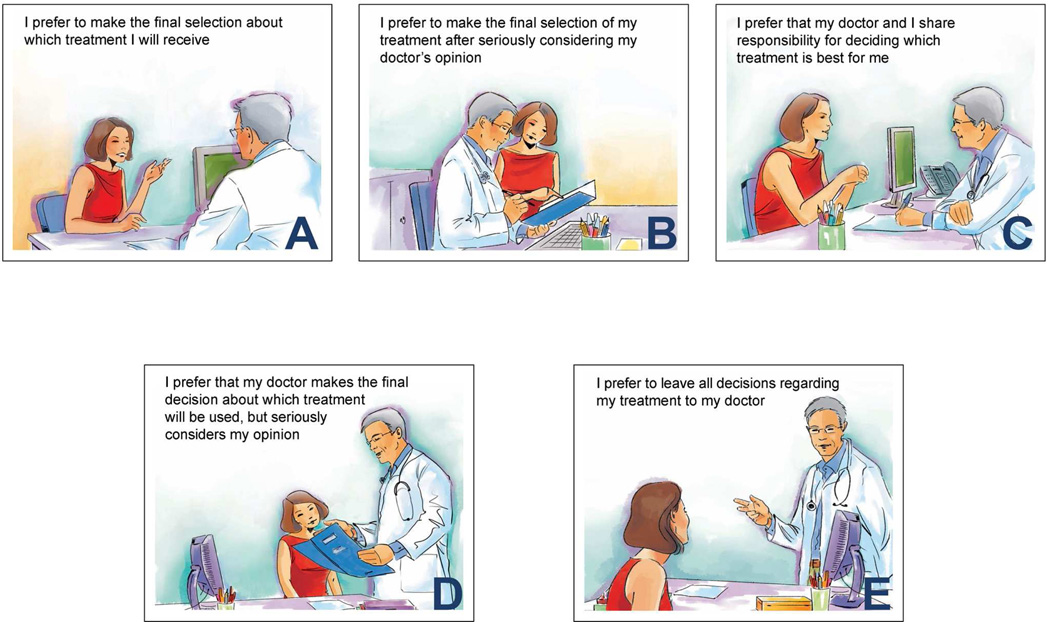

Patients completed surveys characterizing factors that could influence their decision making preferences, including demographic data (age, race, sex, education level, work status, marital status, and living situation), current medical information sources and preferred medium for medical information (physician encounters, pamphlets, videos, websites, articles, books). Health literacy was assessed with 3 standardized questions addressing ability to complete health forms,16 and the EQ-5D-3L was used to quantify perceived general health status.17 Upper extremity disability was evaluated using the Patient Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE), a validated patient-reported questionnaire that quantifies patients’ pain and function.18–20 Although patients had both hand and wrist conditions, the PRWE was chosen instead of the Quick DASH because of the ability of the PRWE to consider pain and function individually. Notably, the PRWE queries tasks performed with the “hand” and has demonstrated construct validity in hand conditions.21, 22 Preferences for participation in medical decision-making were quantified using the Control Preferences Scale. This validated survey uses 5 illustrated cards (A, B, C, D, E) to present a range of potential roles of a patient with respect to their physician during a clinic visit.23All cards illustrate and describe the depicted role of the patient in decision making. Card A illustrates the patient in the most patient-directed role in making medical decisions, C represents a collaborative shared decision approach, and E portrays the most physician-directed role, where the physician alone provides a treatment recommendation (Figure 1). Patients sorted the cards from most to least preferred role in the doctor-patient interaction prior to discussion with the treating surgeon in an effort to prevent same-day interactions from biasing patient responses.

Figure 1.

The Control Preferences Scale cards presented to patients during this study.34

Medical records were reviewed to record the clinic visit type, whether the patient was new to the provider, reason for the clinic visit, and treatment decision at the conclusion of the visit.

Statistical Analysis

The overall data were examined by descriptive statistics for the frequencies and percentages of categorical variables. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed with median and ranges reported for non-normal data.

The primary outcome of this study was the ordered response on the Control Preferences Scale. Descriptive analysis focused on each individually marked preference, particularly a participant’s most and least preferred roles, as described originally for the CPS.23 The validity of our CPS data was confirmed according to the criteria described by Coombs confirming the valid use of a 5 point preference scale in a given population.24 CPS responses were organized into the following roles23:

Active-Active (AB, BA)

Active-Collaborative (BC)

Collaborative-Active (CB)

Collaborative-Passive (CD)

Passive-Collaborative (DC)

Passive-Passive (DE, ED)

Consistent with the work of Obeidat et al., these 6 categories were condensed into 3 groups for bivariate contrasts and regression modeling: patient-directed (1, 2), shared (3, 4), and physiciandirected (5, 6) decision making.25 If a patient’s two most preferred roles did not group adjacent decision making preferences (e.g., A paired with D) then they were excluded from these analyses as that inconsistency in responding indicated potential misunderstanding of the sorting task. Demographic variables (age, sex, race, education, work status, familiarity with provider) were confirmed as not statistically different between those patients excluded and those patients included in analyses. Bivariate analyses were conducted with the chi-square test of independence for categorical patient variables or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous patient variables against the CPS preferences. The absence of confounding due to clustering of patients within physicians was confirmed by assessing the lack of association between composite preference scores and physician encountered.

Multinomial logistic regression modeling evaluated predictors of patients’ preferred treatment role. Variables were entered in a forward step-wise manner based on approaching statistical significance (p<0.10) on bivariate testing. Model fit was confirmed with Pearson and Deviance goodness-of-fit statistics. In the absence of statistically significant predictors, we planned to test for significance of PRWE and patient-reported health literacy because of the hypothesized relevance of the magnitude of upper extremity impairment and health literacy to our study question.

Sample Size Estimation

Ninety-nine patients were enrolled in this cross-sectional study. The study was designed to allow for multinomial logistic regression with at least 5 predictor variables. A conservative estimate was made that 15 subjects were required per predictor variable resulting in a need of 75 participants. We enrolled 99 to allow for potential drop out secondary to refusal to complete all surveys, incomplete data submission, or inconsistent ordering of patient preferences.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic data is provided in Table 1. Ninety-eight percent of participants achieved a minimum education level of high school graduate or GED-equivalent. Eighty percent did not work, of which 98% of this population had retired.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 70 (65–92) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 88 (88%) |

| African-American | 12 (12%) |

| Female | 58 (58%) |

| Education Level | |

| Eighth grade or less | 0 (0%) |

| Some HS | 2 (2%) |

| HS graduate or GED | 20 (20%) |

| Some college | 32 (32%) |

| Four year college graduate | 20 (20%) |

| Post graduate degree | 26 (26%) |

| Current Work Status | |

| Full-time | 9 (9%) |

| Part-time | 9 (9%) |

| Homemaker | 2 (2%) |

| None | 80 (80%) |

| If not working, why? (N=80) | |

| Unemployed | 1 (1%) |

| Retired | 78 (98%) |

| Disabled | 1 (1%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 11 (11%) |

| Living with Partner | 2 (2%) |

| Married | 62 (62%) |

| Separated/ Divorced | 9 (9%) |

| Widowed | 16 (16%) |

| Living Arrangement | |

| Independently and Alone | 28 (28%) |

| With Spouse | 60 (60%) |

| With Children | 7 (7%) |

| Retirement Home | 0 (0%) |

| Assisted Living | 0 (0%) |

| Nursing Home | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 5 (5%) |

Information about the particular clinic visit and patient-reported measures (health, wrist disability) is provided in Table 2. Sixty percent of participants were return patients, and therefore had a pre-established relationship with their hand surgeon prior to this visit.

Table 2.

Patients’ clinic visit characteristics.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinic Visit Reason | |

| OA | 20 (20%) |

| Tendonitis | 29 (29%) |

| Soft-tissue Mass | 12 (12%) |

| Neuropathy | 18 (18%) |

| Soft-tissue Injury | 3 (3%) |

| Fracture | 14 (14%) |

| Other | 4 (4%) |

| Actual Treatment Decision Day Of | |

| None | 22 (22%) |

| Non-operative | 65 (65%) |

| Operative | 13 (13%) |

| New to Provider | 40 (40%) |

| EQ-5D-3L | |

| Mobility | |

| No problems in walking about | 60 (60%) |

| Some problems in walking about | 38 (38%) |

| Confined to a bed | 0 (0%) |

| No response | 2 (2%) |

| Self-Care | |

| No problems with self-care | 86 (86%) |

| Some problems in washing or dressing | 13 (13%) |

| Unable to wash or dress self | 0 (0%) |

| No response | 1 (1%) |

| Usual Activities | |

| No problems with performing usual activities | 59 (59%) |

| Some problems with performing usual activities | 38 (38%) |

| Unable to perform usual activities | 2 (2%) |

| No response | 1 (1%) |

| Pain/ Discomfort | |

| No pain or discomfort | 16 (16%) |

| Moderate pain or discomfort | 74 (74%) |

| Extreme pain or discomfort | 8 (8%) |

| No response | 2 (2%) |

| Anxious/Depressed | |

| Not anxious or depressed | 72 (72%) |

| Moderately anxious or depressed | 27 (27%) |

| Extremely anxious or depressed | 0 (0%) |

| No response | 1 (1%) |

| Health state today (0–100), median (range) | 80 (20–100) |

| PRWE | |

| Pain subscore (0–50), median (range) | 19 (0–42) |

| Function subscore (0–50), median (range) | 16 (0–49) |

| Total (0–100), median (range) | 37 (0–86) |

Information Needs

Eighty-one percent of patients stated they preferred a more active role in decision-making. Forty percent relied on family to help with decisions and 38% relied on their primary care provider. Spending more time with a physician addressing questions and explaining the diagnosis was most frequently ranked as useful to making a healthcare decision (49%). The top 3 sources of background medical information for this population were information from their physician during a clinic appointment (69%), internet searches for credible medical websites (35%), and internet searches for any relevant information without attention to source (18%). Seventy-nine percent preferred information materials in the form of paper handouts. Sixty-two percent indicated that more information about their diagnosis prior to an appointment would improve the usefulness of the appointment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients’ decision preference responses.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Prefer a more active role in decision making? | |

| No | 16 (16%) |

| Yes | 81 (81%) |

| No Response | 3 (3%) |

| Do you rely on anyone else to help with decisions? | |

| Family | 52 (52%) |

| Friends | 12 (12%) |

| PCP | 48 (48%) |

| Other | 13 (13%) |

| Which of the following would you find useful in making a health care decision? |

|

| Second opinion from another provider | 28 (28%) |

| Discussion group with patients facing similar decision | 5 (5%) |

| Unbiased information regarding diagnosis & treatment options | 27 (27%) |

| More time with physician to address questions & explain diagnosis | 57 (57%) |

| Where do you currently get background info on your health issues? | |

| Internet searches for credible medical websites | 35 (35%) |

| Internet searches for any relevant information | 18 (18%) |

| Information packets provided by physicians | 17 (17%) |

| Information from family/friends | 16 (16%) |

| Information from physician during clinic appointment | 69 (69%) |

| Books/articles | 10 (10%) |

| What format would you prefer for informational material? | |

| Paper handouts | 79 (79%) |

| Web page | 18 (18%) |

| Video | 6 (6%) |

| Other | 6 (6%) |

| What should the information packet include? | |

| Information about diagnosis | 90 (90%) |

| Comparison of treatment options | 78 (78%) |

| Pictures demonstrating relevant anatomy | 50 (50%) |

| Risks and benefits associated with treatment | 80 (80%) |

| Graphs or statistics that provide evidence for risks/benefits | 36 (36%) |

| Help considering how personal goals & values align with treatment options |

36 (36%) |

| Guidance in decision-making steps | 36 (36%) |

| Area to brainstorm questions for physicians before clinic appt | 37 (37%) |

| Links to reliable references with more detailed & thorough info | 56 (56%) |

| Would providing more information regarding your diagnosis before your appointment improve the usefulness of the appointment? |

|

| Yes | 62 (62%) |

| No | 7 (7%) |

| Maybe | 30 (30%) |

| No Response | 1 (1%) |

| How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials? | |

| Always | 15 (15%) |

| Often | 8 (8%) |

| Sometimes | 9 (9%) |

| Occasionally | 25 (25%) |

| Never | 41 (41%) |

| No Response | 2 (2%) |

| How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information? |

|

| All of the time | 0 (0%) |

| Most of the time | 1 (1%) |

| Some of the time | 16 (16%) |

| A little of the time | 29 (29%) |

| None of the time | 52 (52%) |

| No Response | 2 (2%) |

| How confident are you filling out forms by yourself? | |

| All of the time | 64 (64%) |

| Most of the time | 23 (23%) |

| Some of the time | 2 (2%) |

| A little of the time | 4 (4%) |

| None of the time | 5 (5%) |

| No Response | 2 (2%) |

Decision-Making Preferences/ Control Preferences Scale

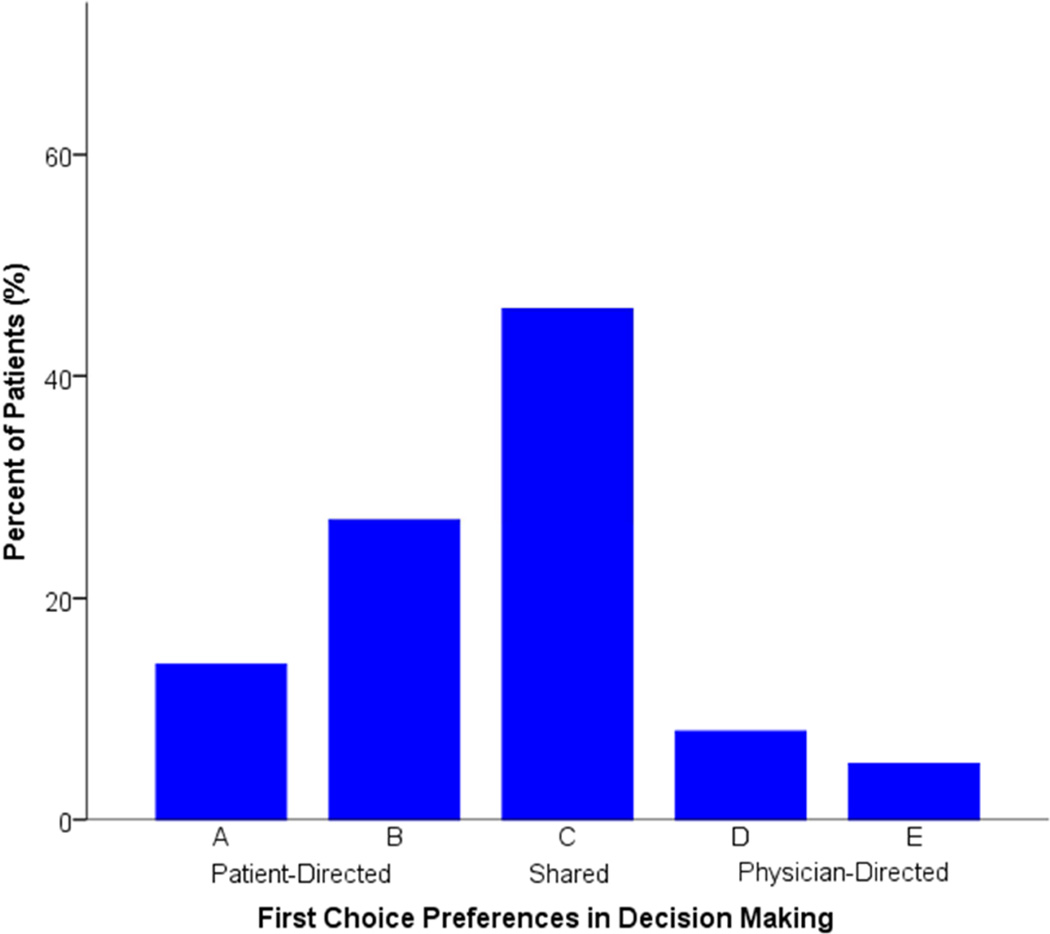

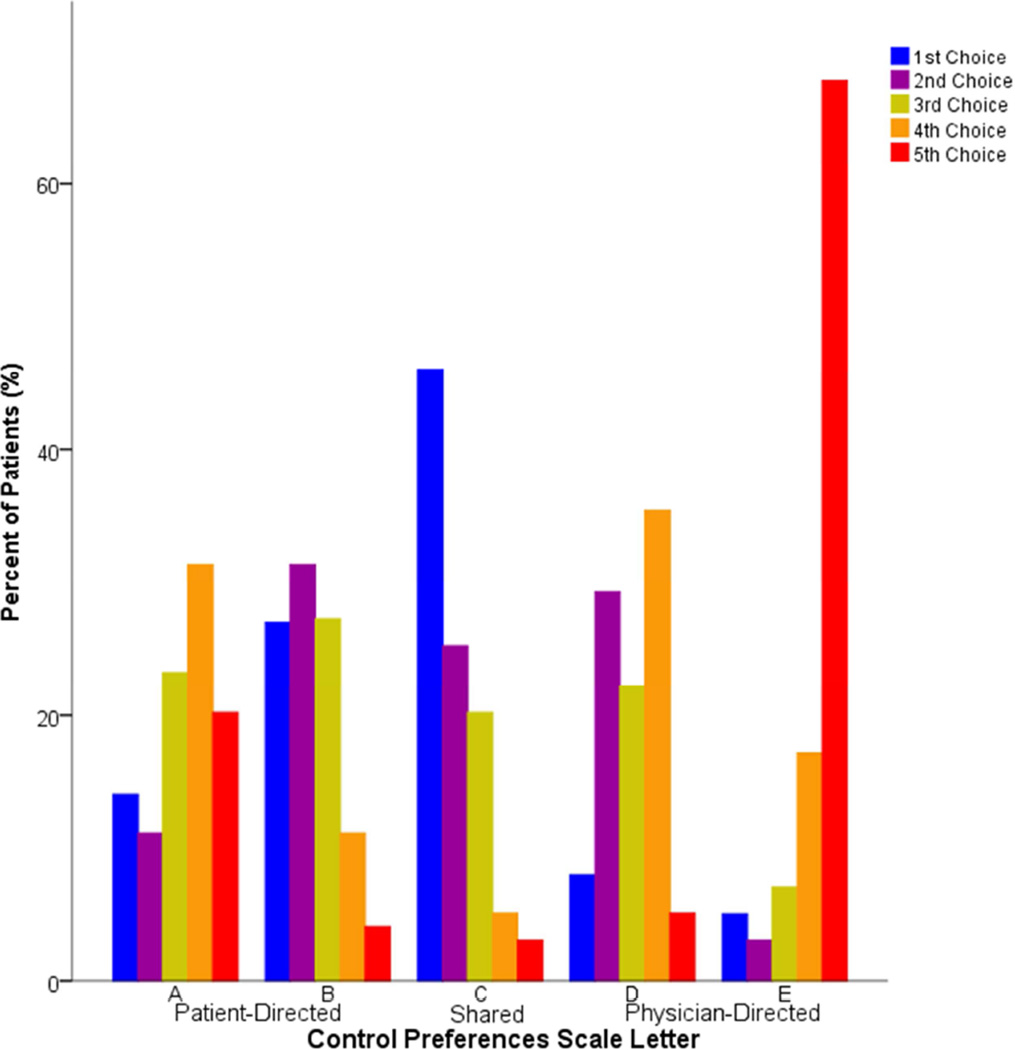

Figure 2 outlines patients’ most preferred CPS interaction card for the 99 enrolled participants. The most frequently preferred card on the Control Preferences Scale was C, which illustrated equitable decision-making with shared responsibility between the patient and doctor, chosen by 46 participants (46%). Card B, representing patient-directed collaboration, was second most preferred, chosen by 27 participants (27%), followed by card A, the most patient-directed end of the scale by 14 subjects (14%). Combined, 87% of patients preferred to be in the shared to patient-directed spectrum of the scale, indicating they wanted to have at least an equal, if not dominant, rolein their ideal health care visit. The least preferred card was E, the completely physician-directed role for the patient, with 67% of participants ranking it as their least preferred role (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Patients’ first choice preferences

Figure 3.

Patients’ ranked preferences

Factors Associated with Decision-Making Preferences

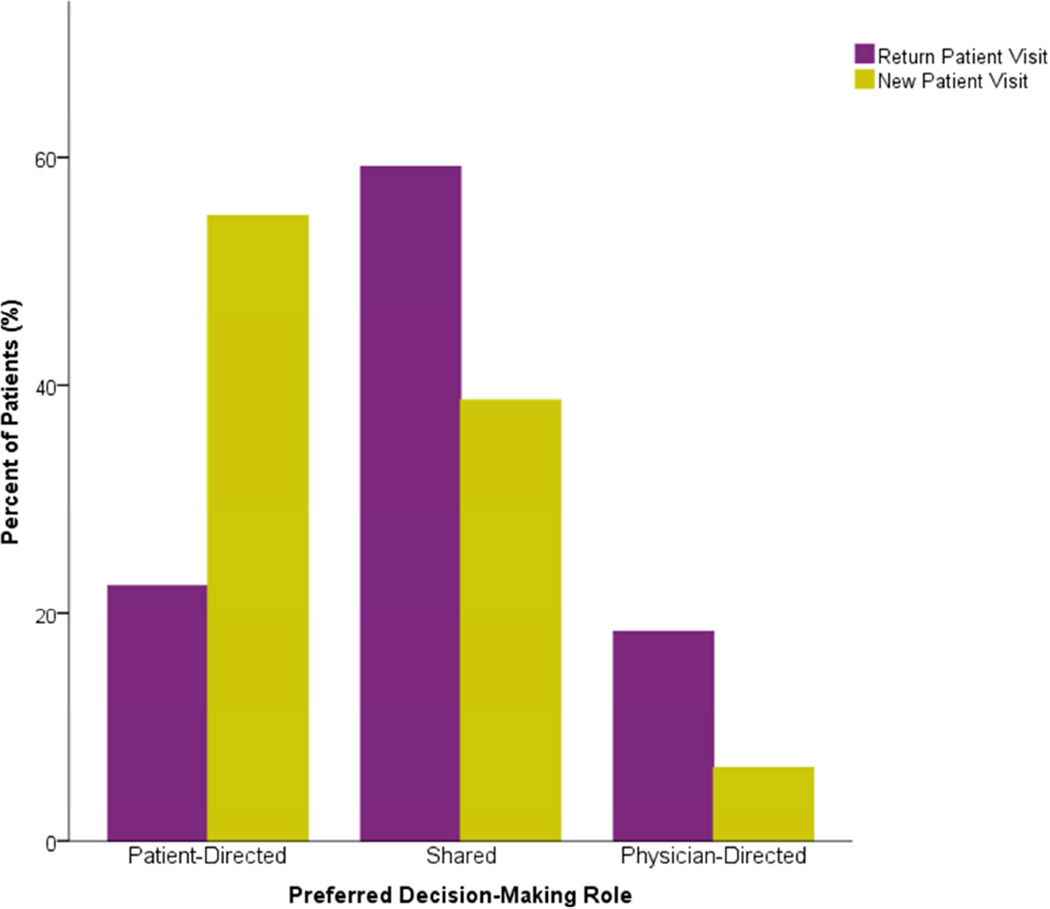

Eighty patients ranked first and second choices that were consistent with the 3-group choice classification, contributing to bivariate contrasts and regression modeling. Bivariate analyses revealed a number of clinic-visit-dependent variables associated with decision-making preferences. Being a return patient to a provider (P<0.05) was associated with being more likely to prefer a shared decision-making (Figure 4). There were no associations between patient age, sex, education level, working status, living arrangement, health literacy measures, patient-reported health status, or magnitude of upper extremity disability with the preferred role in treatment decision-making (Table 4).

Figure 4.

Patients’ preferences by familiarity with provider

Table 4.

Bivariate associations between patients’ demographic, clinic visit, health literacy, quality of life, clinical characteristics, and preferred decision-making role.

| P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Demographic Characteristics |

Age | 0.31 |

| Education Level | 0.20 | |

| Current Work Status | 0.18 | |

| Not Working | 0.72 | |

| Marital Status | 0.82 | |

| Living Arrangement | 0.13 | |

| Race | 0.99 | |

| Sex | 0.51 | |

|

Health Literacy |

How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials? |

0.46 |

| How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information? |

0.85 | |

| How confident are you filling out forms by yourself? | 0.43 | |

|

Clinic Visit Characteristics |

New to Provider | <0.05 |

| Trauma | 0.62 | |

|

EQ-5D Scores |

Mobility | 0.81 |

| Self-Care | 0.40 | |

| Activity | 0.99 | |

| Pain | 0.77 | |

| Anxiety | 0.19 | |

| Health State Today | 0.86 | |

| PRWE Scores | Pain Subscore | 0.37 |

| Function Subscore | 0.24 | |

| Total Score | 0.25 | |

Multi-nomial logistic regression revealed that being new to a provider significantly predicted patient preference for a patient-directed role in decision making against a reference standard of the physician-directed role (P<0.05, ExpB 6.2, 95% CI 1.1–36.0) even when accounting for health literacy (P=0.90) and PRWE score (P=0.46). No independent variables significantly distinguished patient preference for a collaborative role versus a physician-directed role in treatment decisions.

Discussion

Our data contradict prior studies indicate that older adult patients prefer a more physician-directed role in the doctor-patient relationship in comparison to younger adult patients.3,12–15 The Medical Outcomes Study, a four-year observational study exploring American participatory decision making, found a quadratic relationship between age and decision making, where patients <30 and >75 years of age experienced the least participation in making treatment decisions.12 A closer assessment of this older population, however, reveals a changing pattern of preferences. While age continues to impact decision-making preferences, 82% of patients over 60 years old want to share or direct their medical decisions when discussing advanced care planning.2 Our data similarly indicate that when receiving elective specialty hand surgical care, older adult patients want to remain actively involved in their treatment decisions and use their physician visit as their primary source of information.

Shared decision making is the process by which patients and physicians make treatment decisions together with the goal of aligning available treatment options with a patient’s personal values. Federally, shared decision-making is recognized as a key component to patient care. Section 3506 of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) calls for a “Program to Facilitate Shared Decision making”.26 However, increases in cost-consciousness and clinical volume demands decrease the amount of time physicians spend with their patients. The conflict between limited physician time and the need for “preference-sensitive care” requires tools that help assess patient goals and provide unbiased information without creating an undue time burden on providers in clinic. Validated patient decision aids are powerful tools to educate patients about the risks and benefits regarding available treatment options and engage them in discussing personal preferences and beliefs about their care and condition.26 In doing so, patient knowledge and satisfaction improves and patient decision conflict diminishes.4 These tools have been adopted in many other specialties but are lagging in surgical decision making. While this provision remains unfunded today, Section 3506’s message has been incorporated by several other government branches including the Department of Health and Human Service’s Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality’s SHARE approach,27 the Department of Veteran Affairs’ focus on SDM in geriatrics and extended care,28 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service’s quality performance standards set for Accountable Care Organizations to qualify for shared savings.29

Within the field of hand surgery, existing investigations indicate that the values of patients and physicians do not uniformly coincide during treatment for trigger finger or carpal tunnel syndrome.9,10 One survey assessing patients’ and hand surgeons’ preferences on trigger finger treatment found that physicians more strongly preferred corticosteroid injections and surgery while patients exhibited a stronger preference for orthotics.10When assessing operative risk perception among that same group, patients were most concerned about nerve injury while surgeons were most concerned about postoperative stiffness, revealing an opportunity for decision aid use to educate patients about operative risks and align treatment with patients’ values.10 Similarly, physicians and patients agree on the frequency of choosing operative treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome but differ in preferences for non-operative treatment choice and use of electrodiagnostic testing.9 Differences between patient and physician treatment of trigger finger and carpal tunnel syndrome could be due to differences in knowledge of risks and benefits of treatments or priorities in goals of care highlighting two of several preference-sensitive hand conditions for which decision aids could be developed for clinical use. While it is unclear whether decision aids affect one’s choice to pursue elective operative treatment,8,30 patients consistently demonstrate increased knowledge, more accurate risk perception, and make decisions more congruent with their values.4, 31

Our data demonstrate that familiarity with the physician may be a modifier of patient preferences in decision making as return patients were more likely to prefer a shared approach and new patients were more likely to prefer a patient-directed role. This may reflect increased patient trust in a provider’s understanding of their goals and values and willingness to share a decision. This difference may especially be important for older adults presenting with upper-extremity fractures. The management of distal radius fractures in older adults, in particular, has become debated as malunion may be well tolerated.32,33 Provided that a decision for operative fracture treatment is often made at the initial office encounter, using patient decision aids to facilitate SDM may allow patients to decide on a treatment most consistent with their values and long-term goals.

This study has several inherent limitations. The data reflect the experience of one tertiary hand specialty practice in the setting of an academic hospital and may not generalize to all care settings or regions of the country. All enrolled patients lived relatively independently, alone or with spouses, friends, roommates, pets, or children, leaving out a portion of the older adult population living in retirement homes, assisted living facilities, or nursing homes. This skewed sample may be partially due to our exclusion criteria of a mental handicap, dementia, or other degenerative mental disease. Furthermore, the majority of the population was Caucasian, retired, and well-educated. We cannot assume that our data generalize to patients of all cultural or educational backgrounds. While the Control Preferences Scale serves as a widely-accepted validated tool, scoring and presentation of patient preferences varies across studies.23 Preferences can be assessed in multiple ways including focusing on the most preferred role across the 5 categories, or via combining the most preferences into condensed groups.23 In designing this study we felt that analysis was best performed on a summary category system based on patient preferences as previously described25 since it filtered out inconsistent responses where patients marked opposite roles as their two most preferred treatment roles. While this reduced the number of patients available for comparisons, we believe the remaining cohort provided more consistent decision making preferences for analysis. Lastly, while we characterized patients’ initial preferences for decision making and collected data on decisional satisfaction after the encounter, we did not collect data on patients’ perceived level of decision making during their physician encounter, in order to compare the match between initial and perceived decision making preferences to decisional satisfaction as this was beyond the scope of our current study. This may be a future focus of interest, however, especially since older adults patients experience physician-directed decision making more often than their younger counterparts.12, 15

Older adult patients with symptomatic hand conditions desire patient-directed shared roles in orthopedic treatment decision making. Patients’ most strongly desired to actively direct their care when first meeting a physician, suggesting a need for shared decision making and decision aid development for older adults with fractures that are potentially treated operatively after a single office visit. In an era when surgeons may find it difficult to spend more time providing face-to-face counseling as desired by patients during office encounters, educating patients with written materials may improve the productivity and efficiency of conversations regarding treatment options. Although not always possible, screening of patients referred with established diagnoses (e.g., specific fractures or nerve compressions) may allow distribution of educational materials to some new patients. Furthermore, our data suggest that it would be beneficial for surgeons to encourage family involvement during encounters with older adults and that written supplementary information or decision aids for this older population, offer an approach to SDM that is most consistent with the preferences of this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448, sub-award TL1TR000449, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Siteman Comprehensive Cancer Center and NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA091842, which supported the maintenance and use of REDCap electronic data capture tools, hosted in the Biostatistics Division of Washington University School of Medicine.. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. This funding did not play a direct role in this investigation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu C, Feuz M, McMahan R, Miao Y, Sudore R. “Doctor, make my decisions”: decision control preferences, advance care planning, and satisfaction with communication among diverse older adults. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benbassat J, Pilpel D, Tidhar M. Patients’ preferences for participation in clinical decision making: a review of published surveys. Behav Med. 1998;24(2):81–88. doi: 10.1080/08964289809596384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu JH. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slover J, Alvarado C, Nelson C. Shared decision making in total joint replacement. JBone Joint Surg Rev. 2014;2(3):e1. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.M.00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, Durand MA, Sivell S, Stacey D, O'Connor A, Volk RJ, Edwards A, Bennett C, Pignone M, Thomson R, Elwyn G. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified delphi consensus process. Med Decis Mak. 2014;34(6):699–710. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13501721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slover J, Shue J, Koenig K. Shared decision-making in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(4):1046–1053. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozic KJ, Belkora J, Chan V, Youm J, Zhou T, Dupaix J, Bye AN, Braddock CH, 3rd, Chenok KE, Huddleston JI., 3rd Shared decision making in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1633–1639. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hageman MG, Kinaci A, Ju K, Guitton TG, Mudgal CS, Ring D Science of Variation Group. Carpal tunnel syndrome: assessment of surgeon and patient preferences and priorities for decision-making. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(9):1799–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doring A-CD, Hageman MG, Mulder FJ, Guitton TG, Ring D Science of Variation Group. Trigger finger: assessment of surgeon and patient preferences and priorities for decision making. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2208–2213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besdine R, Boult C, Brangman S, Coleman EA, Fried LP, Gerety M, Johnson JC, Katz PR, Potter JF, Reuben DB, Sloane PD, Studenski S, Warshaw G American Geriatrics Society Task Force on the Future of Geriatric Medicine. Caring for older americans: the future of geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(6 Suppl):S245–S256. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan S, Gandek B, Greenfield S, Rogers W, Ware J. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(12):1176–1187. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199512000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2004:531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulter A, Jenkinson C. European patients’ views on the responsiveness of health systems and healthcare providers. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(4):355–360. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, Smith T, Hack TF, Huschka MM, Rummans TA, Clark MM, Diekmann B, Degner LF. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDermid JC, Turgeon T, Richards RS, Beadle M, Roth JH. Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(8):577–586. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt JS, Di Fabio RP. Reliable change and minimum important difference (MID) proportions facilitated group responsiveness comparisons using individual threshold criteria. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1008–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta SP, MacDermid JC, Richardson J, MacIntyre NJ, Grewal R. A systematic review of the measurement properties of the patient-rated wrist evaluation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(4):289–298. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander M, Franko OI, Makhni EC, Zurakowski D, Day CS. Validation of a modern activity hand survey with respect to reliability, construct and criterion validity. J Hand Surg Eur. 2008;33(5):653–660. doi: 10.1177/1753193408093810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imaeda T, Uchiyama S, Wada T, Okinaga S, Sawaizumi T, Omokawa S, Momose T, Moritomo H, Gotani H, Abe Y, Nishida J, Kanaya F Clinical Outcomes Committee of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association and the Functional Evaluation Committee of the Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Japanese version of the Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(4):509–517. doi: 10.1007/s00776-010-1477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coombs CH. A Theory of Data. Wiley; 1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obeidat R. Decision-making preferences of Jordanian women diagnosed with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2281–2285. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.H.R 3590 — 111th Congress: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 27.The SHARE Approach. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed October 2015];2015 Sep; http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html. Updated September 2015.

- 28.Shared Decision Making - Overview. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. [Accessed October 2015];2015 Sep; http://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/Guide/LongTermCare/Shared_Decision_Making.asp.

- 29.Accountable Care Organization 2015 Program Analysis Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 2015];2015 Jan; https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACO-NarrativeMeasures-Specs.pdf.

- 30.Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E, Rutter C, Ross T, McCulloch D, Handley M, Jung C. Introducing decision aids at Group Health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(9):2094–2104. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Weert JC, van Munster BC, Sanders R, Spijker R, Hooft L, Jansen J. Decision aids to help older people make health decisions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:45. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day CS, Daly MC. Management of geriatric distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(12):2619–2622. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldhahn J, Angst F, Simmen BR. What counts: outcome assessment after distal radius fractures in aged patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(8 Suppl):S126–S130. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31817614a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solari A, Giordano A, Kasper J, Drulovic J, van Nunen A, Vahter L, Viala F, Pietrolongo E, Pugliatti M, Antozzi C, Radice D, Köpke S, Heesen C on behalf of the AutoMS project. Role preferences of people with multiple sclerosis: image-revised, computerized self-administered version of the Control Preference Scale. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]