Abstract

Introduction. Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) is a procedure that provides access to the mediastinal staging; however, EBUS cannot be used to stage all of the nodes in the mediastinum. In these cases, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used for complete staging. Objective. To provide a synthesis of the evidence on the diagnostic performance of EBUS + EUS in patients undergoing mediastinal staging. Methods. Systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the diagnostic yield of EBUS + EUS compared with surgical staging. Two researchers performed the literature search, quality assessments, data extractions, and analyses. We produced a meta-analysis including sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratio analysis. Results. Twelve primary studies (1515 patients) were included; two were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and ten were prospective trials. The pooled sensitivity for combined EBUS + EUS was 87% (CI 84–89%) and the specificity was 99% (CI 98–100%). For EBUS + EUS performed with a single bronchoscope group, the sensitivity improved to 88% (CI 83.1–91.4%) and specificity improved to 100% (CI 99-100%). Conclusion. EBUS + EUS is a highly accurate and safe procedure. The combined procedure should be considered in selected patients with lymphadenopathy noted at stations that are not traditionally accessible with conventional EBUS.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the approach to patients with suspected non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), has changed [1]. Several diagnostic and staging methods have been developed to avoid the use of more invasive techniques [2]. Surgical methods, such as mediastinoscopy, video assisted thoracoscopy (VATS), mediastinal dissection, and lymph node resection, are the reference standard for lung cancer lymph node staging. However, minimally invasive methods, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET), as well as bronchoscopic methods, are alternatives with low complication rates and these methods are often used as the first approach for confirming or excluding metastatic disease [2, 3]. One of the limitations of radiological studies is the number of false positive and false negative cases; for this reason, tissue samples are needed for cytopathology or histopathology [2–4].

Over the last decade, bronchoscopic modalities such as endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) have emerged as safe methods to obtain tissue from mediastinal or in close proximity to central airways, with an accuracy of 80–90% and an incidence of complications of less than 1% [4, 5]. This minimally invasive approach is limited to certain mediastinal lymph nodes; however, one of the weaknesses of EBUS-TBNA is its inability to obtain tissue from stations 5, 6, 8, and 9 of the IASLC mediastinal lymph node map [6]. In such cases, a complementary approach with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a safe alternative to obtain tissue from all of the mediastinal lymph nodes, except from stations 5 and 6 [4].

Studies of combined EBUS + EUS have included retrospective, prospective, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published [7, 8] in the past. However, most of the evidence from primary studies has been published in the past five years. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the utility of EBUS + EUS for NSCLC staging or diagnosis in those patients with suspected NSCLC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search and Clinical Eligibility Criteria

Previous descriptions and the protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis are available in the PROSPERO registry (ID: CRD42015017199) [9]. In this systematic review, two independent reviewers searched the following databases: PubMed (Medline), OVID, Lilacs, Clinical Trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), and the Cochrane database. In addition, two metasearches of the TRIP database and Epistemonikos were included up to April 2015 [10]. For maximum sensitivity, meeting abstracts were searched from the European Respiratory Society (ERS; 2008 to 2014), American Thoracic Society (ATS; 2008 to 2014), and American College of Chest Physicians (2008 to 2014).

The search criteria included the following. In the PubMed database, we searched using the following MeSH terms: ((“Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung” [majr]) AND “Bronchoscopy” [majr]) AND “Ultrasonography” [MeSH]. The search also included the following non-MeSH terms: “endobronchial”, “endobronchial ultrasound” (EBUS) alone or in combination with “non-small cell lung carcinoma”, and “neoplasm staging”. The literature search and inclusion criteria were in accordance with the Cochrane handbook and this systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA statement [11].

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review and meta-analysis were the following: (1) patients older than 18 years; (2) confirmed lung cancer with an indication for mediastinal staging (based on enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes); (3) available index test defined as EBUS + EUS with different endoscopes or with the same bronchoscope (EBUS + EUS-B-FNA) and reference standard (surgical methods or clinical followup); and (4) two-by-two diagnostic yield results of specificity, sensitivity, and positive likelihood ratios (LRs).

Two independent authors (GL and CA) performed the literature search, and disagreements concerning study inclusion were resolved by discussion. The full-text versions of the included studies were retrieved, and a manual cross-reference search of the articles was performed with no language restrictions.

2.2. Quality Assessment of the Retrieved Articles

A methodological assessment and quality analysis were performed by two independent reviewers (GL and CA) using the diagnostic test accuracy approach from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [12] and disagreements concerning study inclusion were resolved by discussion.

2.3. Outcomes Measured

We included the diagnostic yield results (specificity, sensitivity, and LR) from all of the included articles in this systematic review and meta-analysis, and a secondary analysis of only EBUS + EUS with fine needle aspiration performed with the same bronchoscope (EBUS + EUS-B- FNA) was performed. In addition, we analysed adverse events related to EBUS + EUS.

For this study we defined the following terms: sensitivity = positive endosonography (EBUS + EUS)/true positive via surgical staging + false negative; specificity = negative endosonography (EBUS + EUS)/true negative via surgical staging + false positive. The patients that were positive during endosonography were considered as true positive.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers (GL and FO). Two-by-two tables were generated that included true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives. Primary study descriptions, population descriptions, types of studies, and reported adverse events were also extracted, and a new summary table was created.

The extracted data were imported into Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA, USA). For the qualitative and quantitative analyses, we used Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.3, and a random effects model was used for the quantitative meta-analysis of diagnostic yield. We defined significant heterogeneity as i 2 > 50% and created a symmetrical summary receiver operatic characteristic curve (SROC); the area under the curve was analysed using MetaDisc, version 1.4. Statistical significance was defined by a p value less than 0.05. We created a summary table of the findings based on the GRADE approach using GRADEpro software.

3. Results

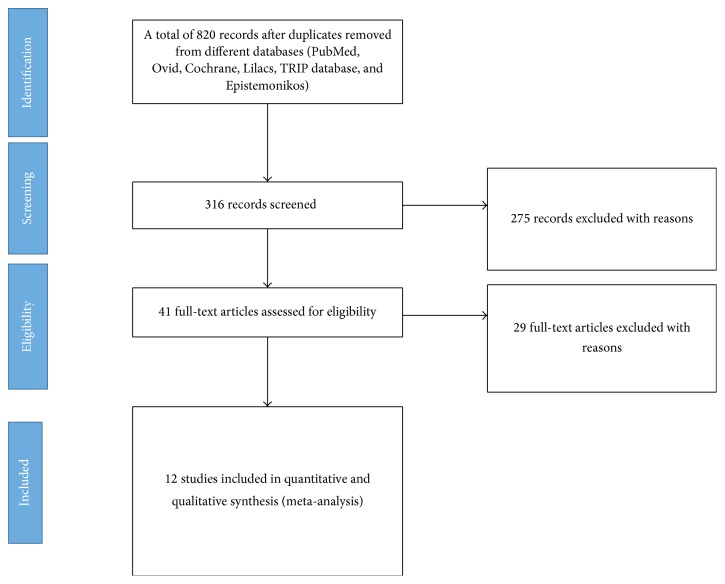

Our search identified 820 records after removing duplicates. 775 references were excluded and a total of 41 potentially eligible primary studies were evaluated in full-text format. After the full-text screening, 29 primary studies were excluded for various reasons [25–54], and 12 primary studies (1515 patients) were included in the qualitative and quantitative analyses and the meta-analysis (Figure 1) [7, 8, 55, 56] [47–54]. No additional studies were identified from conference abstracts. The characteristics of the included and excluded studies are reported in Tables 1 and 5.

Figure 1.

Study of flow diagram following PRISMA statements.

Table 1.

Primary studies included and their characteristics.

| Author | Year | Sample | Patient | Image study | Index test | Outcome | Reference standard | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vilmann et al. [13] | 2005 | 31 | Lung cancer staging or suspected lung cancer | CT scan with suspected mass or lymph node | EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA | Lung cancer staging or diagnosis | Thoracotomy or clinical followup | Prospective trial, non-RCT. 9 patients underwent thoracotomy and 19 had clinical followup. |

|

| ||||||||

| Wallace et al. [14] | 2008 | 138 | Lung cancer staging or suspected lung cancer | CT scan and PET CT with enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA | Lung cancer staging or diagnosis | Thoracotomy, mediastinoscopy, lobectomy, and thoracoscopy | Prospective trial, non-RCT. 33 patients underwent thoracotomy, 4 mediastinoscopy, 4 lobectomy, and 1 thoracoscopy. The rest had 6–12-month clinical followup. |

|

| ||||||||

| Annema et al. [15] | 2010 | 241 | Lung cancer staging, resectable | CT scan and PET CT with enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Mediastinoscopy and/or thoracotomy | RCT, 1 : 1. One arm to endoscopic staging and one arm to surgical staging. Standard reference for this study included thoracotomy in patients without positive endosonography. |

|

| ||||||||

| Herth et al. [16] | 2010 | 139 | Lung cancer staging or suspected lung cancer | CT scan, PET CT in some patients | EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Thoracoscopy, thoracotomy, or clinical followup to 12 months | Prospective study, non-RCT. Timing flow since inclusion is 6–12 months. |

|

| ||||||||

| Hwangbo et al. [17] | 2010 | 150 | Lung cancer staging or suspected lung cancer | CT scan and PET CT with enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Surgery, lymph node dissection | Prospective trial, non-RCT. |

|

| ||||||||

| Szlubowski et al. [18] | 2010 | 120 | Lung cancer staging, stage IA-IIB | CT scan with normal size lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Bilateral transcervical extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy | Prospective trial, non-RCT. Patients with negative EBUS/EUS underwent bilateral transcervical extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy. |

|

| ||||||||

| Ohnishi et al. [19] | 2011 | 110 | Staging for suspected resectable lung cancer | CT scan and PET CT with enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Surgery without any specification | Prospective trial, non-RCT. |

|

| ||||||||

| Szlubowski et al. [20] | 2012 | 214 | Lung cancer staging, stage 1A-IIIB | CT scan | EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Systematic lymph node dissection | Prospective trial, non-RCT. 110 EBUS + EUS and 104 EBUS + EUS-B-FNA. |

|

| ||||||||

| Kang et al. [21] | 2014 | 148 | Staging for confirmed or suspected resectable lung cancer | CT scan and PET CT with enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Surgery without any specification | RCT, 1 : 1. EBUS centered arm versus EUS centered arm using the same bronchoscope. Patients without definitive data were excluded for sensitivity analysis. |

|

| ||||||||

| Lee et al. [22] | 2014 | 44 | Staging for confirmed or suspected lung cancer | PET CT without M1 disease | EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Mediastinoscopy or lymph node resection | Retrospective analysis. 4 patients underwent mediastinoscopy and 4 underwent lymph node resection. |

|

| ||||||||

| Liberman et al. [23] | 2014 | 144 | Staging for confirmed or suspected resectable lung cancer | CT scan and PET CT with enlarged and/or PET positive lymph nodes | EBUS-TBNA + EUS-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Mediastinoscopy or lymph node dissection | Prospective trial, non-RCT. AS per protocol, patients underwent surgical staging following endosonographic staging. |

|

| ||||||||

| Oki et al. [24] | 2014 | 150 | Staging for confirmed or suspected resectable lung cancer | CT scan and PET CT | EBUS-TBNA and EUS-B-FNA | Lung cancer staging | Surgical resection with lymph node dissection or clinical followup | Prospective trial, non-RCT. 5 patients were excluded from analysis without clinical followup. Clinical followup was 6 months after the procedure. |

Table 5.

Excluded studies and motive for exclusion.

| Author | Year | Motive for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Sánchez-Font et al. [25] | 2014 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Schuhmann et al. [26] | 2014 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Yarmus et al. [27] | 2013 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Yarmus et al. [28] | 2013 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Navani et al. [29] | 2012 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Fielding et al. [30] | 2012 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Oki et al. [31] | 2012 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Casal et al. [32] | 2012 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Steinfort et al. [33] | 2011 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Ishida et al. [34] | 2011 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Rintoul et al. [35] | 2009 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Chao et al. [36] | 2009 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Lee et al. [37] | 2008 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Yoshikawa et al. [38] | 2007 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Chung et al. [39] | 2007 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Yasufuku et al. [40] | 2006 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Herth et al. [41] | 2006 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Herth et al. [42] | 2006 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Herth et al. [43] | 2003 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Herth et al. [44] | 2002 | Noninclusion criteria |

| Verhagen et al. [45] | 2013 | Noninclusion criteria |

Two of the included primary studies were RCTs. Annema et al. allocated patients 1 : 1 to an endoscopic staging arm and a surgical arm. In the other RCT, Kang et al. allocated patients 1 : 1 to an EBUS followed by EUS arm and an EUS followed by EBUS arm. These trials were evaluated by two independent researchers and were defined as the best evidence available.

The remaining studies included in the quantitative and qualitative analyses were observational studies. Eleven of these studies were prospective trials, and the other one trial was retrospective in nature.

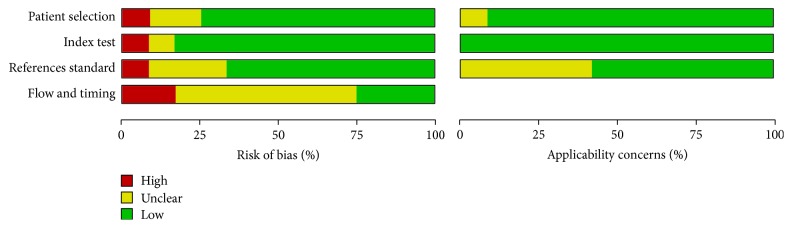

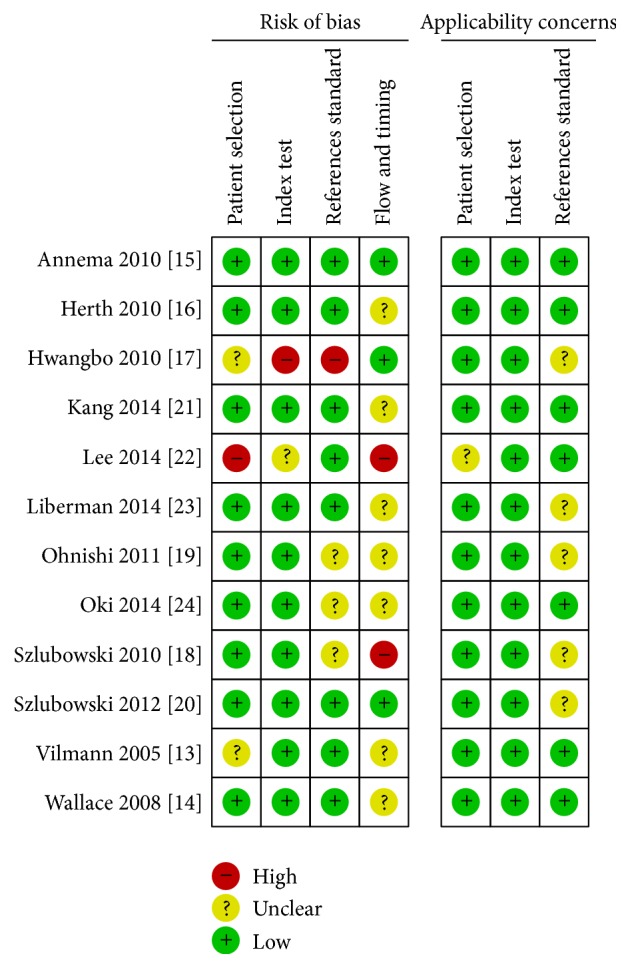

3.1. Risk of Bias in the Included Reviews

A quality assessment of the primary studies was performed using the Cochrane assessment tool. Most of the primary studies reported and addressed a specific question (diagnostic yield from EBUS + EUS for mediastinal staging) without any concern for index testing or reference standard. The limitations of the included studies were the following: (1) no data on the interval since the index test or the reference standard; (2) a risk of bias in the results because some patients in the prospective trials were excluded from the data analysis; (3) some tests including “surgical methods” as reference test, without any specification between mediastinoscopy, thoracotomy, and others; and (4) the study type (10 of the 12 trials were prospective). The results are presented in Figures 2 and 5.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review of authors' judgments about each domain presented as percentages across included studies.

Figure 5.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review of authors' judgments about each domain for each included study.

3.2. Diagnostic Accuracy

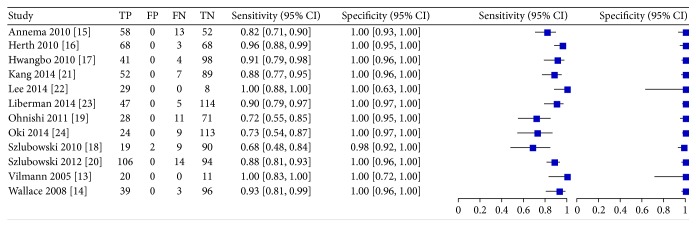

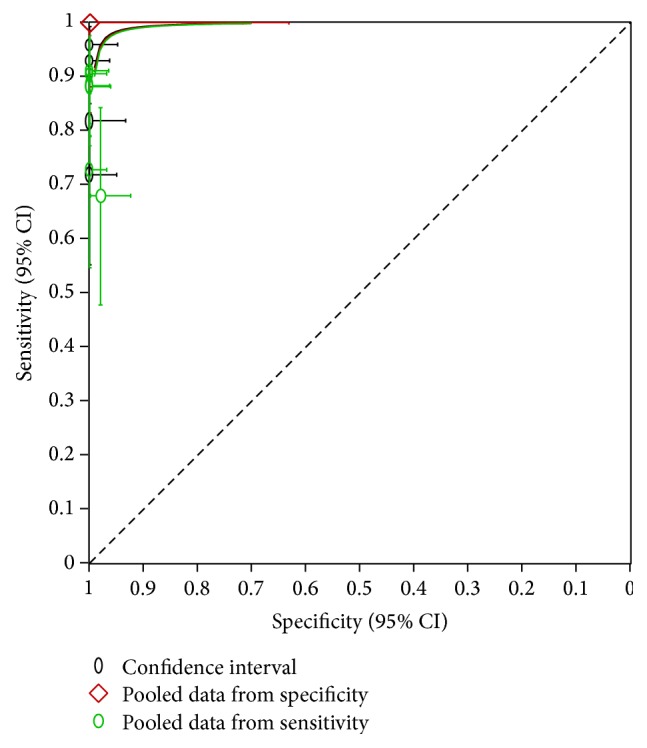

The pooled data from the primary studies that evaluated the diagnostic yield of EBUS + EUS versus surgical methods or clinical followup are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison 1. Forest plot of diagnostic yield from all included studies.

The sensitivity across all the primary studies was 85% (CI 80–89%) and the specificity was 99% (CI 98–100%). The meta-analysis of sensitivity, specificity, and positive likelihood ratio of all the studies and subgroups of EBUS-B-FNA and EBUS + EUS using different endoscopes is reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of meta-analysis of all included studies and subgroup analysis.

| Comparison | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR (+) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All included studies | 87.3% (CI 80–89%; i 2 = 22.86%) | 99% (CI 99-100%; i 2 = 6.69%) | 60.66 (CI 25.27–145.60; i 2 = 3.42%) |

| EBUS + EUS | 85% (CI 80–89%; i 2 = 22.86%) | 99.6% (CI 98.5–100%; i 2 = 6.69%) | 60.66 (CI 25.27–145.6; i 2 = 3.42%) |

| EBUS + EUS-B-FNA | 88% (CI 83.1–91.4%; i 2 = 25.64%) | 100% (CI 99-100%; i 2 = 0%) | 87.67 (CI 28.35–271.07; i 2 = 1.85%) |

LR (+): positive likelihood ratio.

In a subgroup analysis of the EBUS + EUS using different endoscopes revealed a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.6%, compared with EBUS-EUS-B-FNA with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 100%. Finally, SROC analysis revealed an AUC of 0.98 for all of the included primary studies and 0.99 for the EBUS + ESU-B-FNA only. Summaries of these results are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

SROC from all included studies.

Adverse events related to endoscopic procedures were reported in 12 primary studies. The most common adverse event was minor bleeding. Table 2 shows the number of adverse events reported in each trial.

Table 2.

EBUS + EUS adverse events reported in primary studies.

| Author | EBUS + EUS adverse events |

|---|---|

| Vilmann et al. [13] | No complications |

| Wallace et al. [14] | No complications |

| Annema et al. [15] | One case of pneumothorax and 5 minor complications |

| Herth et al. [16] | No complications |

| Hwangbo et al. [17] | One case of lymph node abscess |

| Szlubowski et al. [18] | No complications |

| Ohnishi et al. [19] | No complications |

| Szlubowski et al. [20] | Two cases of nausea and 3 cases of self-limiting abdominal pain |

| Kang et al. [21] | 12 cases of minor bleeding and 1 case of pneumomediastinum |

| Lee et al. [22] | No complications |

| Liberman et al. [23] | One case of bronchial laceration and 1 case of major bleeding |

| Oki et al. [24] | Two cases with severe cough |

Finally, the quality of the evidence in the EBUS + EUS and EBUS + EUS-B-FNA methods was LOW for sensitivity and MODERATE for specificity based on the GRADE approach. A summary of the findings is provided in Tables 4(a) and 4(b).

Table 4.

Summary of finding using GRADE approach. (a) shows EBUS + EUS-B-FNA only; (b) shows pooled data from all included primary studies.

(a) EBUS + EUS pooled sensitivity: 0.87 (95% CI: 0.83 to 0.89) | pooled specificity: 0.99 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.00)

| Test result | Number of results per 1000 patients tested (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 40.2% | |||

|

True positives

(patients with staging) |

350 (334 to 358) | 609 (12) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW1,2 |

|

False negatives

(patients incorrectly classified as not having staging) |

52 (68 to 44) | ||

|

True negatives

(patients without staging) |

592 (592 to 598) | 906 (12) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE3 |

|

False positives

(patients incorrectly classified as having staging) |

6 (6 to 0) |

(b) EBUS-EUS-B-FNA pooled sensitivity: 0.88 (95% CI: 0.83 to 0.91) | pooled specificity: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.00)

| Test result | Number of results per 1000 patients tested (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 40.8% | |||

|

True positives

(patients with staging) |

359 (339 to 371) | 297 (6) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ LOW1,2 |

|

False negatives

(patients incorrectly classified as not having staging) |

49 (69 to 37) | ||

|

True negatives

(patients without staging) |

592 (586 to 592) | 431 (6) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE3 |

|

False positives

(patients incorrectly classified as having staging) |

0 (6 to 0) |

1Low-quality studies.

2Imprecision between different studies

3Different standard reference.

4. Discussion

EBUS is a minimally invasive procedure with good accuracy in confirming or excluding lung cancer or mediastinal lung cancer metastasis. The addition of EUS to EBUS mediastinal staging, however, has improved the sensitivity and accuracy of this method, thereby decreasing the number of unnecessary thoracotomies and surgical procedures [3, 29, 57]. Based on the published data, we recommend EBUS + EUS as the first step for evaluating patients with suspected operable lung cancer or with known operable lung cancer who require mediastinal staging. In the subgroup analysis of EBUS + EUS-B-FNA data only, the sensitivity improved to 88% and the specificity increased to 100%. In addition, there was a significant decrease in the heterogeneity in the EBUS + EUS-B-FNA only group; these data were consistent with the evidence quality of the primary studies. In a systematic review of surgical mediastinal staging published by Silvestri et al. in 2013, traditional mediastinoscopy had a pooled median sensitivity of 78% and NPV of 91% and video assisted mediastinoscopy had a median sensitivity of 89% and NPV of 92% [57]. EBUS + EUS is a safe procedure. In our review, major adverse related events were reported for less than 1% of the procedures; pneumothorax was the most commonly reported complication, these data confirm the safety of this method across multiple studies in different settings [5].

The evidence quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed using Cochrane tools, which include the most influential aspects of diagnostic test methods (patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow, and timing) [12]. We considered the overall quality of all the included primary studies to be low.

The studies included patients with known lung cancer who required mediastinal staging or lesions suspected to be NSCLC. In most cases, a positive pathologic diagnosis with EBUS + EUS was considered a true positive; in patients with negative diagnoses, a second test was performed (surgical methods or clinical followup). This approach is common in clinical practice, and we considered it to be of little concern to the applicability of our results.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis was published by Zhang et al. [8]. In that meta-analysis, the risk of bias was evaluated with the STARD and QUADAS tools, and several trials reported low-quality data. In their study, a positive biopsy with an EBUS + EUS procedure was sufficient to confirm the pathological diagnosis, and surgery was not necessary to confirm the disease [58].

According to ACCP guidelines and previous systematic review and meta-analysis, EBUS alone reports a higher diagnostic yield than EBUS/EUS, Dong et al report a sensitivity of 90% (CI, 84.4–95.7%) and a specificity of 98.4% [55, 57]. However, no head to head comparing EBUS, EBUS/EUS, and mediastinoscopy were identified; we found that a network meta-analysis that includes different mediastinal methods for staging in NSCLC is needed.

According to our results, we suggest that EBUS/EUS performed with the same bronchoscope has a higher yield than these performed with separate bronchoscope and endoscope; however, these are not head to head comparisons; so it is difficult to determine what to make of these findings but they are intriguing.

Finally, training is certainly an issue that merits further research. There appears to be a paucity of training in these combined techniques; EUS performed by an interventional pulmonology (not by gastroenterologist trained in EUS) is not taught in most interventional pulmonary fellowships; this fact should be considered as a potential training for interventional pulmonary fellowship programs.

We found some bias in our study. In several studies the reference standards were suboptimal. Mediastinoscopy has an accuracy that is comparable to endosonography. Mediastinoscopy is potentially therefore a suboptimal reference standard and, if used alone, this will lead to overestimations of the accuracy of endosonography. We considered this fact as a major source of bias, and we determined that the protocol of another systematic review was incomplete (PROSPERO ID: CRD42014009792) [56]. We considered this systematic review and meta-analysis as part of the current body of evidence for our study. Limitations of this approach to integrating evidence include the following. First, several nonrandomized studies had different inclusion criteria such as mediastinal masses or lung masses suspected of cancer and included patients with potentially benign lesions. Second, the preprocedure evaluation was not reported in several studies. Some did include the use of PET-CT as part of the preprocedure evaluation. Third, for negative endoscopic procedures, we had concerns about the reference standard. Some patients were excluded from the data analysis in some studies, and in other studies, the final diagnosis was declared using methods other than mediastinoscopy or surgical procedures. All of these various criteria might have introduced heterogeneity in the trials and the RCT data were limited to two trials. More primary studies and RCTs are needed to improve the body of evidence.

5. Conclusion

Based on previous primary studies published, this systematic review is the most complete evidence-based synthesis today, including all diagnostic test studies and best quality studies (RCTs) analysed by Cochrane criteria. Based upon this analysis, we believe that EBUS + EUS is a minimally invasive and highly accurate method for mediastinal staging that is associated with a low incidence of complications. While the diagnostic yield is not superior to EBUS alone, the combined procedure should be considered in selected patients with lymphadenopathy noted at stations that are not traditionally accessible with conventional EBUS. However, most of the available data are from high-quality observational studies. Additional studies are necessary to improve the quality of evidence.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Dr. Carlos Aravena and Gonzalo Labarca perform conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, data analysis, preparation of the manuscript, and final proof read. Dr. Francisco Ortega, Alex Arenas, and Sebastian Fernandez-Bussy perform the acquisition of data, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Adnan Majid, Erik Folch, Hiren J. Mehta, and Michael A. Jantz perform the critical analysis and final proof read. All authors approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Alberg A. J., Brock M. V., Ford J. G., Samet J. M., Spivack S. D. Epidemiology of lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5):e1S–e29S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivera M. P., Mehta A. C., Wahidi M. M. Establishing the diagnosis of lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5, supplement 1):e142S–e165S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dincer H. E. Linear EBUS in staging non-small cell lung cancer and diagnosing benign diseases. Journal of Bronchology & Interventional Pulmonology. 2013;20(1):66–76. doi: 10.1097/lbr.0b013e31827d1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilmann P., Puri R. The complete ‘medical’ mediastinoscopy (EUS-FNA + EBUS-TBNA) Minerva Medica. 2007;98(4):331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Bartheld M. B., Van Breda A., Annema J. T. Complication rate of endosonography (endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound): a systematic review. Respiration. 2014;87(4):343–351. doi: 10.1159/000357066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rusch V. W., Asamura H., Watanabe H., Giroux D. J., Rami-Porta R., Goldstraw P. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2009;4(5):568–577. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3181a0d82e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu P., Zhao Y.-Z., Jiang L.-Y., Zhang W., Xin Y., Han B.-H. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45(8):1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang R., Ying K., Shi L., Zhang L., Zhou L. Combined endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer. 2013;49(8):1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VRV6BJPF8VM. Minimally invasive methods for staging of mediastinum in lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2015, http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015017199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Rada G., Perez D., Capurro D. Epistemonikos: a free, relational, collaborative, multilingual database of health evidence. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2013;192:486–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7, article e1000100) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shuster J. J. Review: cochrane handbook for systematic reviews for interventions, Version 5.1.0, published 3/2011. Julian P.T. Higgins and Sally Green, Editors. Research Synthesis Methods. 2011;2(2):126–130. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilmann P., Krasnik M., Larsen S. S., Jacobsen G. K., Clementsen P. Transesophageal endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) biopsy: a combined approach in the evaluation of mediastinal lesions. Endoscopy. 2005;37(9):833–839. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace M. B., Pascual J. M. S., Raimondo M., et al. Minimally invasive endoscopic staging of suspected lung cancer. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(5):540–546. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Annema J. T., Van Meerbeeck J. P., Rintoul R. C., et al. Mediastinoscopy vs endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(20):2245–2252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herth F. J. F., Krasnik M., Kahn N., Eberhardt R., Ernst A. Combined endoscopic-endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes through a single bronchoscope in 150 patients with suspected lung cancer. Chest. 2010;138(4):790–794. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwangbo B., Lee G.-K., Lee H. S., et al. Transbronchial and transesophageal fine-needle aspiration using an ultrasound bronchoscope in mediastinal staging of potentially operable lung cancer. Chest. 2010;138(4):795–802. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szlubowski A., Zieliński M., Soja J., et al. A combined approach of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided needle aspiration in the radiologically normal mediastinum in non-small-cell lung cancer staging—a prospective trial. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2010;37(5):1175–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohnishi R., Yasuda I., Kato T., et al. Combined endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer. Endoscopy. 2011;43(12):1082–1089. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szlubowski A., Soja J., Kocoń P., et al. A comparison of the combined ultrasound of the mediastinum by use of a single ultrasound bronchoscope versus ultrasound bronchoscope plus ultrasound gastroscope in lung cancer staging: a prospective trial. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2012;15(3):442–446. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang H. J., Hwangbo B., Lee G.-K., et al. EBUS-centred versus EUS-centred mediastinal staging in lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2014;69(3):261–268. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee K. J., Suh G. Y., Chung M. P., et al. Combined endobronchial and transesophageal approach of an ultrasound bronchoscope for mediastinal staging of lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091893.e91893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberman M., Sampalis J., Duranceau A., Thiffault V., Hadjeres R., Ferraro P. Endosonographic mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer. Chest. 2014;146(2):389–397. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oki M., Saka H., Ando M., Kitagawa C., Kogure Y., Seki Y. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: are two better than one in mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer? The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2014;148(4):1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sánchez-Font A., Giralt L., Vollmer I., Pijuan L., Gea J., Curull V. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions. A Controlled Study with Fluoroscopy. Archivos de Bronconeumologia. 2014;50(5):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuhmann M., Bostanci K., Bugalho A., et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided cryobiopsies in peripheral pulmonary lesions: a feasibility study. The European Respiratory Journal. 2014;43(1):233–239. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00011313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarmus L. B., Akulian J., Lechtzin N., et al. Comparison of 21-gauge and 22-gauge aspiration needle in endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: results of the american college of chest physicians quality improvement registry, education, and evaluation registry. Chest. 2013;143(4):1036–1043. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarmus L. B., Akulian J. A., Gilbert C., et al. Comparison of moderate versus deep sedation for endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2013;10(2):121–126. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201209-074OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navani N., Brown J. M., Nankivell M., et al. Suitability of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration specimens for subtyping and genotyping of non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study of 774 patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;185(12):1316–1322. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0294oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fielding D. I., Chia C., Nguyen P., et al. Prospective randomised trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guide sheath versus computed tomography-guided percutaneous core biopsies for peripheral lung lesions. Internal Medicine Journal. 2012;42(8):894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oki M., Saka H., Kitagawa C., et al. Randomized study of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy: thin bronchoscopic method versus guide sheath method. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2012;7(3):535–541. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3182417e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casal R. F., Staerkel G. A., Ost D., et al. Randomized clinical trial of endobronchial ultrasound needle biopsy with and without aspiration. Chest. 2012;142(3):568–573. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinfort D. P., Vincent J., Heinze S., Antippa P., Irving L. B. Comparative effectiveness of radial probe endobronchial ultrasound versus CT-guided needle biopsy for evaluation of peripheral pulmonary lesions: a randomized pragmatic trial. Respiratory Medicine. 2011;105(11):1704–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida T., Asano F., Yamazaki K., et al. Virtual bronchoscopic navigation combined with endobronchial ultrasound to diagnose small peripheral pulmonary lesions: a randomised trial. Thorax. 2011;66(12):1072–1077. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.145490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rintoul R. C., Tournoy K. G., El Daly H., et al. EBUS-TBNA for the clarification of PET positive intra-thoracic lymph nodes-an international multi-centre experience. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2009;4(1):44–48. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3181914357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chao T.-Y., Chien M.-T., Lie C.-H., Chung Y.-H., Wang J.-L., Lin M.-C. Endobronchial ultrasonography-guided transbronchial needle aspiration increases the diagnostic yield of peripheral pulmonary lesions: a randomized trial. Chest. 2009;136(1):229–236. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H. S., Lee G. K., Lee H.-S., et al. Real-time endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: how many aspirations per target lymph node station? Chest. 2008;134(2):368–374. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshikawa M., Sukoh N., Yamazaki K., et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath for peripheral pulmonary lesions without X-ray fluoroscopy. Chest. 2007;131(6):1788–1793. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung Y.-H., Lie C.-H., Chao T.-Y., et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography with distance for peripheral pulmonary lesions. Respiratory Medicine. 2007;101(4):738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasufuku K., Nakajima T., Motoori K., et al. Comparison of endobronchial ultrasound, positron emission tomography, and CT for lymph node staging of lung cancer. Chest. 2006;130(3):710–718. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herth F. J. F., Eberhardt R., Becker H. D., Ernst A. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in fluoroscopically invisible solitary pulmonary nodules: a prospective trial. Chest. 2006;129(1):147–150. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herth F. J. F., Ernst A., Eberhardt R., Vilmann P., Dienemann H., Krasnik M. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes in the radiologically normal mediastinum. European Respiratory Journal. 2006;28(5):910–914. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00124905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herth F. J., Becker H. D., Ernst A. Ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: an experience in 242 patients. Chest. 2003;123(2):604–607. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herth F. J. F., Ernst A., Becker H. D. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in solitary pulmonary nodules and peripheral lesions. The European Respiratory Journal. 2002;20(4):972–974. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00032001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verhagen A. F., Schuurbiers O. C. J., Looijen-Salamon M. G., van der Heide S. M., van Swieten H. A., van der Heijden E. H. F. M. Mediastinal staging in daily practice: endosonography, followed by cervical mediastinoscopy. Do we really need both? Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2013;17(5):823–828. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Navani N., Nankivell M., Lawrence D. R., et al. Lung cancer diagnosis and staging with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration compared with conventional approaches: an open-label, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2015;3(4):282–289. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00029-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharples L. D., Jackson C., Wheaton E., et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound relative to surgical staging in potentially resectable lung cancer: results from the ASTER randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment. 2012;16(18):1–81. doi: 10.3310/hta16180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dooms C., Tournoy K. G., Schuurbiers O., et al. Endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of clinical N1 non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective multicenter study. Chest. 2015;147(1):209–215. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cerfolio R. J., Bryant A. S., Eloubeidi M. A., et al. The true false negative rates of esophageal and endobronchial ultrasound in the staging of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2010;90(2):427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bugalho A., Ferreira D., Eberhardt R., et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for accessible lung cancer lesions after non-diagnostic conventional techniques: a prospective study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13, article 130 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Block M. I. Transition from mediastinoscopy to endoscopic ultrasound for lung cancer staging. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2010;89(3):885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhooria S., Aggarwal A., Singh N., et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration with an echobronchoscope in undiagnosed mediastinal lymphadenopathy: first experience from India. Lung India. 2015;32(1):6–10. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.148399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rintoul R. C., Skwarski K. M., Murchison J. T., Wallace W. A., Walker W. S., Penman I. D. Endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided real-time fine-needle aspiration for mediastinal staging. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;25(3):416–421. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00095404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zielinski M., Szlubowski A., Kołodziej M., et al. Comparison of endobronchial ultrasound and/or endoesophageal ultrasound with transcervical extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy for staging and restaging of non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8(5):630–636. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e318287c0ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dong X., Qiu X., Liu Q., Jia J. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2013;96(4):1502–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. VRWDaZPF8VM, Minimally invasive endoscopic staging for mediastinal lymphadenopathy in lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2014, http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014009792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Silvestri G. A., Gonzalez A. V., Jantz M. A., et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5):e211–e250. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bossuyt P. M., Reitsma J. B., Bruns D. E., et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(1):W1–W12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]