Abstract

Background: Epidemiologic evidence on dietary carbohydrates and stroke risk remains controversial. Very few prospective cohort studies have been conducted in Asian populations, who usually consume a high-carbohydrate diet and have a high burden of stroke.

Objective: We examined dietary glycemic index (GI), glycemic load (GL), and intakes of refined and total carbohydrates in relation to risks of total, ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke and stroke mortality.

Design: This study included 64,328 Chinese women, aged 40–70 y, with no history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or cancer. A validated, interviewer-administered food-frequency questionnaire was used to assess usual dietary intakes at baseline and during follow-up. Incident stroke cases and deaths were identified via follow-up interviews and death registries and were confirmed by review of medical records and death certificates.

Results: During mean follow-ups of 10 y for stroke incidence and 12 y for stroke mortality, we ascertained 2991 stroke cases (2750 ischemic and 241 hemorrhagic) and 609 stroke deaths. After potential confounders were controlled for, we observed significant positive associations of dietary GI and GL with total stroke risk; multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for high compared with low levels (90th compared with 10th percentile) were 1.19 (1.04, 1.36) for GI and 1.27 (1.04, 1.54) for GL (both P-linearity < 0.05 and P-overall significance < 0.05). Similar linear associations were found for ischemic stroke, but the associations with hemorrhagic stroke appeared to be J-shaped. Similar trends of positive associations with stroke risks were suggested for refined carbohydrates but not for total carbohydrates. No significant associations were found for stroke mortality after multivariable adjustment.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that high dietary GI and GL, primarily due to high intakes of refined grains, are associated with increased risks of total, ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke in middle-aged and older urban Chinese women.

Keywords: dietary carbohydrates, glycemic index, glycemic load, stroke, prospective cohort

INTRODUCTION

Since being defined 3 decades ago, the glycemic index (GI)8 has been recognized as an important measure of dietary carbohydrate quality, reflecting the postprandial glucose response (1). Meanwhile, glycemic load (GL), which further incorporates the amount of available carbohydrates in foods, measures both the quality and quantity of dietary carbohydrates (2). Foods with high GI and GL can cause marked fluctuations in blood glucose and insulin concentrations, stimulate lipogenesis, increase oxidative stress, and impair endothelial function (3, 4). A high-GI and high-GL diet has been associated with several cardiometabolic diseases, notably type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease (5–8). However, epidemiologic evidence on the associations of dietary GI and GL with stroke has been less consistent.

Significant positive associations were observed between dietary GL and stroke risk in the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition)-Italy study (9) and between dietary GI and stroke mortality in an Australian cohort (10) and among Japanese women (11). Other prospective cohort studies reported associations in certain subgroups of study participants or for certain subtypes of stroke. For example, the Nurses’ Health Study found a strong GL-stroke association among women with a BMI (in kg/m2) of ≥25, but not among normal-weight women (12). The EPIC-MORGEN study found a significant GI-stroke association among Dutch men but not among women (13). A Swedish cohort reported that GL was associated with hemorrhagic stroke (14), whereas the EPIC-Greece cohort reported an association of GL with only ischemic stroke (15). It is likely that the associations of dietary GI and GL with stroke risk or mortality are population-specific and influenced by participant characteristics, exposure levels, and food sources of carbohydrates and other dietary variables (16). To our knowledge, except for a report by Oba et al. (11) on associations of GI and GL with stroke mortality among Japanese adults, no publication has examined these associations in Asian populations, who usually consume high-carbohydrate, high-GI diets while bearing a heavy and growing burden of stroke (17).

Previously, in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS), we reported that high GI and GL and high carbohydrate intakes, mainly in the form of refined carbohydrates from white rice, were associated with increases of ∼30% in risks of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease among Chinese women (18, 19). In the present investigation, we examined dietary GI, GL, and intakes of total and refined carbohydrates in relation to stroke risk and mortality and explored whether the associations differed by stroke subtypes or were modified by major stroke risk factors.

METHODS

Study population

The SWHS is a population-based, prospective cohort study that recruited 74,941 Chinese women (aged 40–70 y) from December 1996 to May 2000 in urban communities of Shanghai, China (participation rate: 92.7%). Details on the study design and recruitment methods have been published elsewhere (20). Briefly, in-person interviews were conducted at baseline by using structured questionnaires to obtain information on participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, diet, lifestyle, and medical history. Anthropometric measurements were also taken during the interviews. Participants have been re-visited every 2–4 y to update their health and lifestyle information (follow-up rates: ≥92%). Annual linkages to the Shanghai Vital Statistics Registry have been used to update participants’ vital status and to ascertain dates and causes of deaths (completion rate: >99%). The SWHS was approved by the institutional review boards of the Shanghai Cancer Institute and Vanderbilt University. All of the participants provided written informed consent.

Dietary assessment

Usual dietary intakes were assessed by using a validated food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) at baseline for all cohort members and were reassessed 2–3 y later at the first follow-up interview for ∼91% of cohort members (21). Participants were asked about the frequency (daily, weekly, monthly, yearly, or never) and average amount [in liang (50 g)] they consumed for each food or food group during the preceding year. Total energy and nutrient intakes were calculated by using the 2002 Chinese Food-Composition Tables (22). The FFQ was validated in a subset of the SWHS against multiple 24-h dietary recalls that were recorded every 2 wk consecutively for 1 y. The correlation coefficients were 0.66 for total carbohydrates, 0.60 for total protein, 0.59 for total fat, 0.66 for grains, 0.48–0.58 for meats, and 0.41–0.55 for fruit and vegetables, which suggested reasonably good validity for the assessment of intakes of macronutrients and major food groups by the FFQ. The GI values of foods were extracted from the Chinese Food-Composition Tables as well as the International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values (23, 24). Methods for calculating dietary GI and GL have been described previously (19). Refined carbohydrates were defined as carbohydrates from white rice and refined-wheat products (noodles, steamed bread, and flour-based desserts). To improve the assessment of usual dietary intakes and to account for possible dietary changes during follow-up, we used both baseline intakes and the average intakes of 2 FFQs and modeled them as time-varying variables (25). For persons who did not complete the second FFQ or who reported having stroke, coronary artery disease, diabetes, or cancer diagnosed between 2 surveys, only the baseline diet was used as the exposure.

Outcome ascertainment

The primary outcome of this study was incident stroke that occurred between the baseline and the fourth follow-up interviews. A diagnosis of stroke was confirmed by reviewing medical records and by using criteria adapted from the US National Survey of Stroke: evidence of sudden or rapid onset of neurologic deficits that persist for >24 h or until death and have no apparent nonvascular causes, such as trauma, tumor, or infection (26). Only confirmed cases were considered events in the analysis. Ischemic stroke or hemorrhagic stroke was determined on the basis of clinical findings, computerized tomography, MRI scans of the brain, and/or angiographic findings. The secondary outcome was death from stroke. Stroke deaths were defined as an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code of 430–438 listed as the underlying cause of death on the death certificate.

Statistical analysis

We excluded women who had a history of cardiovascular disease or cancer at baseline (n = 7999) and women who reported extreme energy intakes (<500 or >3500 kcal/d; n = 110). We also excluded women with a history of diabetes (n = 2504), because we found that those with prevalent diabetes generally reported lower intakes of carbohydrates, suggesting diet changes after diagnosis. A total of 64,328 women were included in the analysis. For the stroke incidence analysis, follow-up time was counted from the date of the baseline interview to the date of stroke diagnosis, death, loss to follow-up, or the fourth follow-up interview (the latest date: 31 December 2011), whichever came first. For the stroke mortality analysis, follow-up time was counted from the date of the baseline interview to the date of death, loss to follow-up, or 31 December 2013 (the latest linkage to the death certificates), whichever came first.

Dietary intakes were adjusted for total energy intake by using the residual method (27). Baseline characteristics of study participants were compared across quintiles of dietary GI by using general linear regression for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess HRs and 95% CIs with age as the time scale. GI, GL, and carbohydrate intakes were modeled as restricted cubic spline functions to account for possible nonlinear relations. Three knots at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles were chosen on the basis of a better model fitness. The 10th percentile was set as the reference point; HRs (95% CIs) were estimated for the 30th, 50th, 70th, and 90th percentiles. Models were stratified by birth cohort (5-y intervals) and adjusted for potential confounders, including educational attainment (less than high school, high school, professional education, or college and above), family history of stroke (yes or no), cigarette smoking (never or ever), BMI (kg/m2), history of hypertension (yes or no), history of dyslipidemia (yes or no), total energy intake (kilocalories per day), and saturated fat intake (grams per day). Dietary intakes and disease history were updated during follow-up and modeled as time-varying covariates. We also adjusted for a partial diet quality score that was calculated for each participant by assessing adherence to the 2007 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese (28), with exclusion of a component score of grains and their products from the total score. This partial diet quality score included component scores of 9 food groups: vegetables, fruit, dairy products, legumes, meat and poultry, fish and shrimp, eggs, total fat, and salt. Additional adjustment for household income, alcohol consumption, leisure-time physical activity, waist-to-hip ratio, menopausal status, use of hormone therapy, and use of aspirin did not significantly change the associations of GI, GL, and carbohydrates with stroke risk or mortality; therefore, these variables were not included in the final model.

Multiplicative interactions were determined by likelihood ratio test for GI with potential stroke risk factors, including education, smoking, BMI, family history of stroke, history of hypertension, history of dyslipidemia, and saturated fat intake. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding early years (the first 2 y) of observation to address the potential influence of preclinical disease on the risk estimates. In addition, we re-conducted the analyses by examining only the baseline diet or the most recent diet, by using the density method to adjust for total energy intake (27), and by categorizing GI, GL, and carbohydrate intakes into quintiles. All P values were 2-sided and considered significant when <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

At baseline (1996–2000), the median dietary GI in the SWHS was 75.6 (10th–90th percentile range: 69.5–80.0) and the median GL was 210 (10th–90th percentile range: 173–245). On average, 93% of GL came from white rice and refined-wheat products. Women with a higher dietary GI were older, less educated, and more likely to smoke cigarettes, be overweight, and have a history of hypertension than women with a lower dietary GI (Table 1). A higher dietary GI was also associated with less saturated fat intake and a lower diet quality score.

TABLE 1.

Age-adjusted baseline characteristics by baseline dietary glycemic index in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study in 64,328 Chinese women (1996–2000)1

| Quintile of glycemic index |

||||||

| Characteristics | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P2 |

| Participants, n | 12,865 | 12,866 | 12,866 | 12,866 | 12,865 | — |

| Glycemic index3 | 34.2–71.8 | 71.8–74.5 | 74.5–76.5 | 76.5–78.6 | 78.6–86.1 | — |

| Glycemic load | 179 ± 20 | 199 ± 20 | 210 ± 20 | 220 ± 20 | 238 ± 20 | <0.0001 |

| Refined carbohydrate intake,4 g/d | 190 ± 24 | 222 ± 24 | 240 ± 24 | 256 ± 24 | 281 ± 24 | <0.0001 |

| Total carbohydrate intake, g/d | 263 ± 24 | 274 ± 24 | 281 ± 24 | 286 ± 24 | 299 ± 24 | <0.0001 |

| Age, y | 49.7 ± 7.8 | 50.6 ± 8.3 | 51.1 ± 8.5 | 51.9 ± 8.9 | 54.1 ± 9.4 | <0.0001 |

| High educational attainment,5 % | 20.0 | 17.1 | 14.2 | 11.3 | 6.0 | <0.0001 |

| Ever smoker, % | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 5.0 | <0.0001 |

| Family history of stroke, % | 18.1 | 18.4 | 17.6 | 17.4 | 15.5 | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.7 ± 3.3 | 23.8 ± 3.3 | 23.7 ± 3.3 | 23.8 ± 3.3 | 24.2 ± 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| History of hypertension, % | 17.2 | 18.6 | 18.6 | 20.2 | 22.1 | <0.0001 |

| History of dyslipidemia, % | 13.1 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 13.2 | 0.68 |

| Total energy intake, kcal/d | 1690 ± 394 | 1697 ± 393 | 1685 ± 393 | 1669 ± 393 | 1680 ± 396 | 0.72 |

| Saturated fat intake, g/d | 9.9 ± 2.8 | 8.8 ± 2.8 | 8.3 ± 2.8 | 7.7 ± 2.8 | 6.5 ± 2.8 | <0.0001 |

| Partial diet quality score6 | 29.8 ± 3.9 | 29.7 ± 3.9 | 29.2 ± 3.9 | 28.4 ± 3.9 | 26.1 ± 3.9 | 0.0001 |

Values are means ± SDs unless otherwise indicated.

Differences in continuous variables were examined by the general linear regression model and in categorical variables by the chi-square test.

Values are ranges.

Refined carbohydrates were defined as carbohydrates from white rice and refined-wheat products.

High educational attainment was defined as professional education, college, or graduate education.

Diet quality score was calculated by assessing adherence to the 2007 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese (28). To examine the health effect of carbohydrates, the component score for consumption of grains and their products was excluded from the total score.

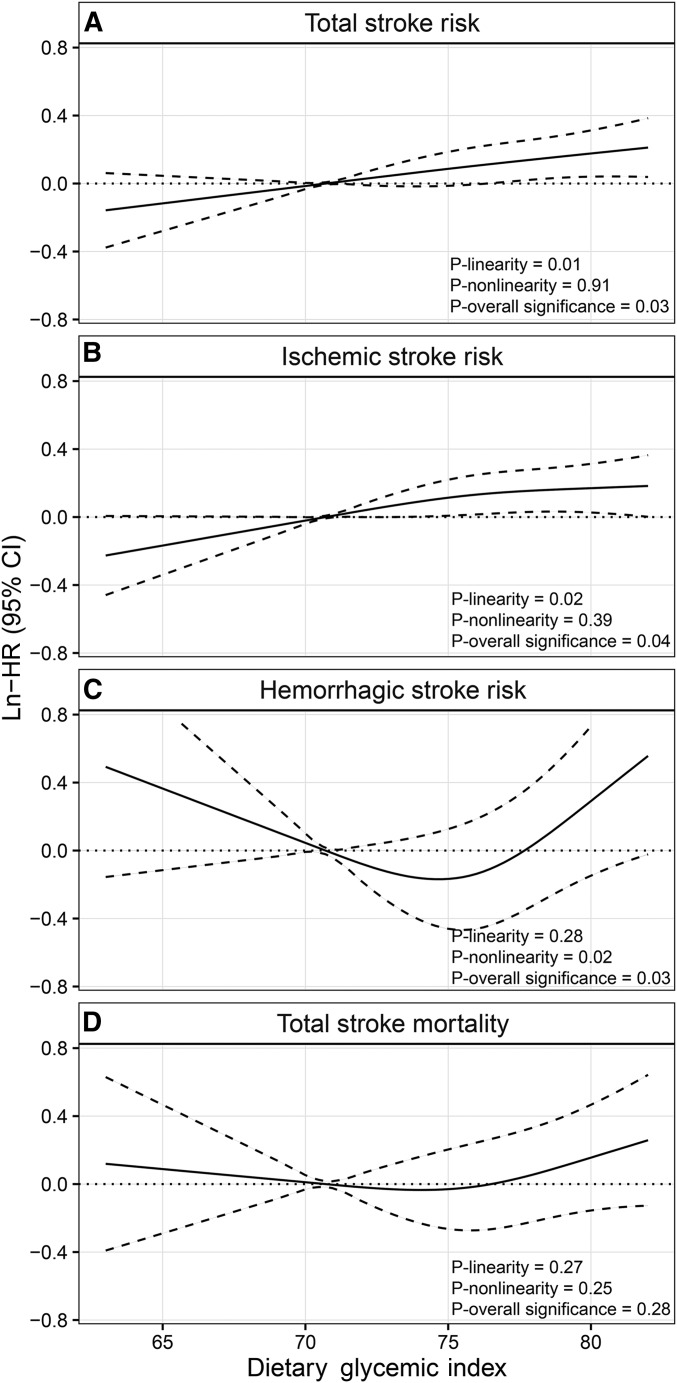

During a mean follow-up of 10 y (618,412 total person-years), we ascertained 2991 incident strokes. In the age- and energy-adjusted model, GI, GL, and intakes of refined and total carbohydrates were all significantly associated with an increased risk of developing stroke (Table 2). In models that further adjusted for other potential confounders, dietary GI and GL remained significantly associated with total stroke risk. HRs (95% CIs) at the 90th compared with the 10th percentile were 1.19 (1.04, 1.36) for GI (P-linearity = 0.01, P-nonlinearity = 0.91, and P-overall significance = 0.03; Table 2, Figure 1A) and 1.27 (1.04, 1.54) for GL (P-linearity = 0.02, P-nonlinearity = 0.36, and P-overall significance = 0.047). Refined carbohydrates and their main food sources, white rice and refined-wheat products, showed similar trends of positive, linear associations with total stroke risk, although these were not significant: HRs (95% CIs) at the 90th compared with the 10th percentile were 1.20 (1.01, 1.42) for refined carbohydrates (P-overall significance = 0.08) and 1.18 (0.99, 1.40) for refined grains (P-overall significance = 0.11). Total carbohydrate intake was not associated with stroke risk in the multivariable-adjusted model.

TABLE 2.

HRs (95% CIs) for total stroke by dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and intakes of refined and total carbohydrates in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study in 64,328 Chinese women (1996–2011)1

| Percentile of dietary measures |

||||||||

| 10th | 30th | 50th | 70th | 90th | P-linear | P-nonlinear | P-overall | |

| Glycemic index | 71 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 80 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21) | 1.20 (1.08, 1.33) | 1.28 (1.15, 1.43) | 1.39 (1.25, 1.56) | <0.0001 | 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) | 1.11 (1.00, 1.24) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29) | 1.19 (1.04, 1.36) | 0.01 | 0.91 | 0.03 |

| Glycemic load | 174 | 194 | 207 | 220 | 239 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.23 (1.11, 1.35) | 1.31 (1.18, 1.45) | 1.42 (1.28, 1.58) | <0.0001 | 0.45 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32) | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | 1.27 (1.04, 1.54) | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.047 |

| Refined carbohydrates, g/d | 189 | 217 | 236 | 254 | 280 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.23 (1.11, 1.35) | 1.30 (1.17, 1.45) | 1.40 (1.26, 1.56) | <0.0001 | 0.35 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.09 (1.00, 1.18) | 1.14 (1.01, 1.28) | 1.17 (1.02, 1.34) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.42) | 0.048 | 0.30 | 0.08 |

| Total carbohydrates, g/d | 246 | 266 | 278 | 291 | 308 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.29) | 1.25 (1.13, 1.37) | 1.35 (1.22, 1.50) | <0.0001 | 0.90 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) | 1.10 (0.95, 1.28) | 1.13 (0.94, 1.36) | 1.17 (0.92, 1.47) | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

ref, referent.

Cox model, with age as the time scale, was stratified by 5-y birth cohort and adjusted for education, cigarette smoking, BMI, family history of stroke, history of hypertension, history of dyslipidemia, total energy intake, saturated fat intake, and a partial diet quality score. Dietary intakes and disease history were modeled as time-varying variables.

FIGURE 1.

Smoothed plot for multivariable-adjusted HRs in a natural-log scale for total stroke risk (A), ischemic stroke risk (B), hemorrhagic stroke risk (C), and stroke mortality (D) (number of events = 2991, 2750, 241, and 609 for panels A–D, respectively) in association with dietary glycemic index in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (n = 64,328). The ln-HRs were estimated by using the restricted cubic spline proportional hazards model with 3 knots at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of glycemic index. The 10th percentile was treated as the referent. Point estimates are indicated by solid lines and 95% CIs by dashed lines.

Among incident stroke cases, there were 2750 cases of ischemic stroke and 241 cases of hemorrhagic stroke. After potential confounders were controlled for, significant associations were found for dietary GI with both risks of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (Table 3; P-overall significance < 0.05 for both). Interestingly, cubic spline curves suggested a linear association of GI with ischemic stroke (Figure 1B; P-linearity = 0.02), whereas the association with hemorrhagic stroke appeared to be J-shaped (Figure 1C; P-nonlinearity = 0.02). The risk of hemorrhagic stroke increased after GI reached 78 (the 70th percentile). Again, the results for GL and refined carbohydrates were similar to those for GI but were not significant. Total carbohydrate intake was not associated with a risk of any subtype of stroke.

TABLE 3.

HRs (95% CIs) for ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke by dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and intakes of refined and total carbohydrates in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study in 64,328 Chinese women (1996–2011)1

| Percentile of dietary measures |

||||||||

| 10th | 30th | 50th | 70th | 90th | P-linear | P-nonlinear | P-overall | |

| Ischemic stroke | ||||||||

| Glycemic index | 71 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 80 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.15 (1.05, 1.25) | 1.23 (1.10, 1.38) | 1.30 (1.16, 1.46) | 1.38 (1.22, 1.55) | <0.0001 | 0.60 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.10 (1.00, 1.20) | 1.14 (1.02, 1.28) | 1.17 (1.03, 1.32) | 1.18 (1.03, 1.36) | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

| Glycemic load | 174 | 194 | 207 | 220 | 239 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.24) | 1.25 (1.12, 1.38) | 1.32 (1.18, 1.47) | 1.40 (1.25, 1.56) | <0.0001 | 0.16 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.11 (1.02, 1.22) | 1.18 (1.03, 1.35) | 1.22 (1.04, 1.43) | 1.25 (1.02, 1.53) | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.049 |

| Refined carbohydrates, g/d | 189 | 217 | 236 | 254 | 280 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.16 (1.08, 1.25) | 1.26 (1.13, 1.40) | 1.32 (1.18, 1.48) | 1.38 (1.23, 1.55) | <0.0001 | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.11 (1.02, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.32) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.37) | 1.18 (0.99, 1.42) | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Total carbohydrates, g/d | 246 | 266 | 278 | 291 | 308 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.11 (1.03, 1.19) | 1.18 (1.07, 1.30) | 1.24 (1.12, 1.37) | 1.33 (1.19, 1.48) | <0.0001 | 0.63 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.19) | 1.12 (0.96, 1.30) | 1.15 (0.95, 1.39) | 1.18 (0.92, 1.51) | 0.21 | 0.50 | 0.36 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | ||||||||

| Glycemic index | 71 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 80 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 0.87 (0.69, 1.12) | 0.95 (0.70, 1.29) | 1.18 (0.86, 1.62) | 1.69 (1.20, 2.39) | 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.21) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.43) | 1.29 (0.85, 1.97) | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Glycemic load | 174 | 194 | 207 | 220 | 239 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.23) | 1.04 (0.76, 1.43) | 1.22 (0.87, 1.71) | 1.73 (1.22, 2.44) | 0.0003 | 0.04 | 0.0002 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 0.98 (0.73, 1.30) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.56) | 1.13 (0.67, 1.92) | 1.43 (0.73, 2.80) | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Refined carbohydrates, g/d | 189 | 217 | 236 | 254 | 280 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 0.91 (0.73, 1.14) | 0.96 (0.70, 1.30) | 1.14 (0.82, 1.58) | 1.70 (1.21, 2.39) | 0.0001 | 0.006 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 0.90 (0.70, 1.17) | 0.92 (0.62, 1.34) | 1.03 (0.65, 1.63) | 1.36 (0.76, 2.44) | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Total carbohydrates, g/d | 246 | 266 | 278 | 291 | 308 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.05 (0.83, 1.33) | 1.14 (0.83, 1.58) | 1.31 (0.93, 1.84) | 1.70 (1.19, 2.42) | 0.002 | 0.23 | 0.003 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 0.95 (0.68, 1.34) | 0.94 (0.56, 1.58) | 0.95 (0.50, 1.81) | 0.99 (0.43, 2.27) | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.90 |

ref, referent.

Cox model, with age as the time scale, was stratified by 5-y birth cohort and adjusted for education, cigarette smoking, BMI, family history of stroke, history of hypertension, history of dyslipidemia, total energy intake, saturated fat intake, and a partial diet quality score. Dietary intakes and disease history were modeled as time-varying variables.

During a mean follow-up of 12 y (956,144 total person-years), we ascertained 609 stroke deaths. All of these 4 measures of dietary carbohydrates were significantly associated with increased stroke mortality in age- and energy-adjusted model (Table 4). However, after full adjustment for potential confounding factors, the positive association disappeared.

TABLE 4.

HRs (95% CIs) for total stroke death by dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and intakes of refined and total carbohydrates in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study in 64,328 Chinese women (1996–2013)1

| Percentile of dietary measures |

||||||||

| 10th | 30th | 50th | 70th | 90th | P-linear | P-nonlinear | P-overall | |

| Glycemic index | 71 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 80 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) | 1.13 (0.88, 1.46) | 1.32 (1.02, 1.71) | 1.67 (1.29, 2.16) | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 0.97 (0.79, 1.18) | 0.99 (0.76, 1.28) | 1.05 (0.80, 1.38) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.56) | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| Glycemic load | 174 | 194 | 207 | 220 | 239 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.24) | 1.14 (0.91, 1.44) | 1.32 (1.03, 1.68) | 1.73 (1.36, 2.20) | <0.0001 | 0.06 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.00 (0.82, 1.22) | 1.04 (0.78, 1.40) | 1.13 (0.79, 1.61) | 1.33 (0.86, 2.08) | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| Refined carbohydrates, g/d | 189 | 217 | 236 | 254 | 280 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.06 (0.90, 1.25) | 1.15 (0.91, 1.45) | 1.32 (1.04, 1.69) | 1.73 (1.36, 2.21) | <0.0001 | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 1.00 (0.83, 1.20) | 1.03 (0.78, 1.35) | 1.11 (0.81, 1.53) | 1.30 (0.88, 1.93) | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| Total carbohydrates, g/d | 246 | 266 | 278 | 291 | 308 | |||

| Age- and energy-adjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | 1.25 (1.00, 1.56) | 1.63 (1.30, 2.04) | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted2 | 1 (ref) | 0.94 (0.76, 1.18) | 0.94 (0.68, 1.32) | 0.99 (0.66, 1.50) | 1.12 (0.66, 1.91) | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

ref, referent.

Cox model, with age as the time scale, was stratified by 5-y birth cohort and adjusted for education, cigarette smoking, BMI, family history of stroke, history of hypertension, history of dyslipidemia, total energy intake, saturated fat intake, and a partial diet quality score. Dietary intakes and disease history were modeled as time-varying variables.

In stratified analyses (Supplemental Table 1), we found no significant interactions between dietary GI and stroke risk factors, although the GI and stroke association appeared to be more pronounced among women who had a family history of stroke or had no history of hypertension. Results were basically unchanged in sensitivity analyses and in analyses that used alternative analytic approaches. When omitting the first 2 y of follow-up, the multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI) for total stroke risk at the 90th compared with the 10th percentile of GI was 1.24 (1.07, 1.42) (P-overall significance = 0.01). HRs (95% CIs) for total stroke risk at the 90th compared with the 10th percentile of GI were 1.13 (1.00, 1.27) when examining only the baseline diet and 1.15 (1.00, 1.31) when examining only the recent diet. Results were similar when using the nutrient density method to adjust for total energy intake, with an HR (95% CI) of 1.21 (1.02, 1.45) at the 90th compared with the 10th percentile of refined-carbohydrate intake. HRs (95% CIs) for stroke risk and mortality by quintiles of GI, GL, and carbohydrate intakes are shown in Supplemental Tables 2–4. Results for total and ischemic stroke risk from the categorical analysis were consistent with those from the analysis that used the restricted cubic spline approach (Tables 2–4). However, only the latter approach showed a nonlinear (J-shaped) association between GI and hemorrhagic stroke risk (Figure 1C).

DISCUSSION

In this large, prospective cohort study in urban Chinese women, dietary GI, GL, and probably refined carbohydrates, but not total carbohydrates, were associated with increased risks of total, ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke. These associations were independent of several established cardiovascular disease risk factors and were robust in analyses that used different methods of dietary assessment, energy adjustment, and statistical modeling.

The positive associations of dietary GI and GL with stroke were not unexpected in our study population. We previously reported significant associations in the SWHS of GI and GL with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease (18, 19), which share many risk factors with stroke, such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. The inclusion of these comorbidities (dyslipidemia and hypertension) in the model as potential mediators and/or confounders attenuated but did not eliminate the associations between GI and GL and stroke risk. Current studies that measured retinal venular caliber and cerebral oxygen metabolic rate suggested mechanisms involving microvascular injuries and cerebral oxidative stress, which may, in part, further explain the detrimental effects of a high-GI and high-GL diet and high postprandial glycemia on cerebrovascular health (10, 29). When discussing dietary GI and GL in relation to cardio-cerebrovascular disease, it is important to consider intake amounts and food sources of carbohydrates in different populations. Our study population of middle-aged and older urban Chinese women habitually consumed a high-GI and high-GL diet. The average dietary GI of 76 and GL of 210 are among the highest reported by existing studies, in which the average GI ranges from 53 to 78 and GL ranges from 100 to 210 (9–15). Moreover, in the SWHS, dietary GI and GL are predominantly contributed by white rice and refined-wheat products, which are high-GI, high-carbohydrate, low-fiber, and low-micronutrient staple foods. It was carbohydrates from these refined grains, rather than total carbohydrates, that were associated with stroke risk in our population. Similarly, the EPIC-Italy study found a significant association with stroke risk for high-GI carbohydrates (mainly from white bread) but not for low-GI carbohydrates (cutoff = 57) (9); and the Japanese study found that the association of GI with stroke mortality was mainly driven by GI related to white rice consumption (11). Therefore, when taking into consideration both exposure amounts and carbohydrate sources, the association of dietary GI and GL and stroke risk may be more likely to be detected in populations with high intakes of carbohydrates from refined grains, such as our urban Chinese population and the Japanese and Italian populations mentioned above (9, 11). Conversely, a null association may be more likely to be found in populations with relatively low intakes of carbohydrates and refined grains (13–15, 30).

The GI/GL–stroke association may differ by stroke subtypes; however, few individual cohorts have had sufficient power to examine stroke risk by subtype, especially for hemorrhagic stroke. A meta-analysis that summarized 5 prospective studies and included 1595 ischemic and 670 hemorrhagic stroke cases and deaths estimated that RRs (95% CIs) were 1.35 (1.06, 1.72) for ischemic stroke and 1.09 (0.81, 1.47) for hemorrhagic stroke in the highest compared with the lowest GL category (15). In the SWHS, we observed an ∼20% increase in ischemic stroke risk and a 30–40% increase in hemorrhagic stroke risk when comparing women at the 90th percentile with those at the 10th percentile of GI and GL. We also observed that the increase in ischemic stroke risk appeared to be linear, although it seemed to slow down after GI reached a high level (>78, the 70th percentile); in contrast, hemorrhagic stroke risk increased significantly beyond a GI of 78. It is intriguing to observe a J-shaped association between GI and hemorrhagic stroke risk in our study population who generally consumes a high-GI and high-GL diet. In the future, large studies or pooling analyses are needed to further examine stroke subtypes and to quantify the dose-response relation of GI and GL with stroke risks.

Strengths of our study include its population-based prospective design, high follow-up rates, repeated dietary measurements, and a large sample size of medical record–confirmed stroke cases. Nevertheless, we acknowledge several limitations of the study. First, measurement errors could affect the estimation of dietary GI and GL. Due to an incomplete coverage of GI in the Chinese Food-Composition Tables, we had to extract some GI values from the International Tables (24), which may not well represent the GI values of local foods in Shanghai. Even the GI values from the Chinese tables were only estimates, because GI of foods can vary with botanical variety and cooking methods (24). However, the homogeneity of our participants (all were ethnic Chinese women from a small geographic area, of similar age, and free of major chronic diseases) should reduce the measurement errors. Moreover, GI and GL were primarily determined by intakes of staple foods, and their intakes assessed by our FFQ have been shown to be fairly accurate (21). Second, residual or unknown confounders could bias the observed associations. Although we adjusted for a number of stroke risk factors (e.g., sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diet quality), we could not rule out confounding from poorly measured or unmeasured confounders.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence that a high-GI and high-GL diet, mainly due to a high consumption of refined grains, may increase stroke risk among middle-aged and older urban Chinese women. To our knowledge, this is the first large Asian cohort to examine dietary GI, GL, and intakes of total and refined carbohydrates in relation to risks of stroke in general, ischemic stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke. Given the high intakes of refined carbohydrates and the high burden of stroke in Asian populations, our findings may have important public health implications for stroke prevention in these populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bethanie Rammer for her assistance in editing the manuscript.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—DY, XZ, X-OS, Y-BX, Y-TG, WZ, and GY: were responsible for the study concept and design; DY, XZ, X-OS, HC, WZ, and GY: analyzed and interpreted the data; DY and GY: drafted the manuscript; GY: had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: collected and managed the data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors had any conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; GI, glycemic index; GL, glycemic load; SWHS, Shanghai Women’s Health Study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, Barker H, Fielden H, Baldwin JM, Bowling AC, Newman HC, Jenkins AL, Goff DV. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmerón J, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Wing AL, Willett WC. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 1997;277:472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2002;287:2414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson S, Brand-Miller J. Glycemic index, postprandial glycemia and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 2005;16:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwood DC, Threapleton DE, Evans CEL, Cleghorn CL, Nykjaer C, Woodhead C, Burley VJ. Glycemic index, glycemic load, carbohydrates, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 2013;36:4166–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhupathiraju SN, Tobias DK, Malik VS, Pan A, Hruby A, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 3 large US cohorts and an updated meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:218–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirrahimi A, de Souza RJ, Chiavaroli L, Sievenpiper JL, Beyene J, Hanley AJ, Augustin LSA, Kendall CWC, Jenkins DJA. Associations of glycemic index and load with coronary heart disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:e000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong J-Y, Zhang Y-H, Wang P, Qin L-Q. Meta-analysis of dietary glycemic load and glycemic index in relation to risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:1608–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sieri S, Brighenti F, Agnoli C, Grioni S, Masala G, Bendinelli B, Sacerdote C, Ricceri F, Tumino R, Giurdanella MC, et al. Dietary glycemic load and glycemic index and risk of cerebrovascular disease in the EPICOR cohort. PLoS One 2013;8:e62625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaushik S, Wang JJ, Wong TY, Flood V, Barclay A, Brand-Miller J, Mitchell P. Glycemic index, retinal vascular caliber, and stroke mortality. Stroke 2009;40:206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K, Fujii K, Kawachi T, Takatsuka N, Shimizu H. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and intake of carbohydrate and rice in relation to risk of mortality from stroke and its subtypes in Japanese men and women. Metabolism 2010;59:1574–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh K, Hu FB, Cho E, Rexrode KM, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Liu S, Willett WC. Carbohydrate intake, glycemic index, glycemic load, and dietary fiber in relation to risk of stroke in women. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burger KNJ, Beulens JWJ, Boer JMA, Spijkerman AMW, van der A DL. Dietary glycemic load and glycemic index and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in Dutch men and women: the EPIC-MORGEN study. PLoS One 2011;6:e25955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitan EB, Mittleman MA, Håkansson N, Wolk A. Dietary glycemic index, dietary glycemic load, and cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and older Swedish men. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1521–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossi M, Turati F, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, La Vecchia C, Trichopoulou A. Relation of dietary glycemic load with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: a cohort study in Greece and a meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 2015;54:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan J, Song Y, Wang Y, Hui R, Zhang W. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and stroke mortality: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e52182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston SC, Mendis S, Mathers CD. Global variation in stroke burden and mortality: estimates from monitoring, surveillance, and modelling. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villegas R, Liu S, Gao Y-T, Yang G, Li H, Zheng W, Shu XO. Prospective study of dietary carbohydrates, glycemic index, glycemic load, and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged Chinese women. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu D, Shu X-O, Li H, Xiang Y-B, Yang G, Gao Y-T, Zheng W, Zhang X. Dietary carbohydrates, refined grains, glycemic load, and risk of coronary heart disease in Chinese adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1542–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng W, Chow W-H, Yang G, Jin F, Rothman N, Blair A, Li H-L, Wen W, Ji B-T, Li Q, et al. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:1123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shu XO, Yang G, Jin F, Liu D, Kushi L, Wen W, Gao Y-T, Zheng W. Validity and reproducibility of the food frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Wang G, Pan X, editors. [Chinese Food-Composition Tables 2002.] Beijing (China): Peking University Medical Press; 2002 (in Chinese).

- 23.Yang Y-X, Wang H-W, Cui H-M, Wang Y, Yu L-D, Xiang S-X, Zhou S-Y. Glycemic index of cereals and tubers produced in China. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:3430–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care 2008;31:2281–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Ascherio A, Rosner BA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:531–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker AE, Robins M, Weinfeld FD. The National Survey of Stroke: clinical findings. Stroke 1981;12:I13–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(Suppl):1220S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu D, Zhang X, Xiang Y-B, Yang G, Li H, Gao Y-T, Zheng W, Shu X-O. Adherence to dietary guidelines and mortality: a report from prospective cohort studies of 134,000 Chinese adults in urban Shanghai. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu F, Liu P, Pascual JM, Xiao G, Huang H, Lu H. Acute effect of glucose on cerebral blood flow, blood oxygenation, and oxidative metabolism. Hum Brain Mapp 2015;36:707–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beulens JWJ, de Bruijne LM, Stolk RP, Peeters PHM, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. High dietary glycemic load and glycemic index increase risk of cardiovascular disease among middle-aged women: a population-based follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]