Abstract

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system is a useful tool for genome editing. In this study, using a microinjection-based CRISPR/Cas9 system, we efficiently generated mouse lines carrying mutations at the Irx3 and Irx5 loci, which are located in close proximity on a chromosome and are functionally redundant. During the generation of Irx3/Irx5 double mutant mice, a deletion of ~0.5 Mb between the Irx3 and Irx5 loci was unintentionally identified in 6 out of 27 living pups by PCR based genotyping analysis. This deletion was confirmed by DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of fibroblasts. These results indicate that the mutant mice with a deletion of at least 0.5 Mb in their genome can be generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system through microinjection into fertilized eggs. Our findings expand the utility of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in production of disease model animals with large deletions.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, Genome editing, Large deletion, Mouse

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system, which comprises a single guide RNA (sgRNA) and an RNA-guided DNA nuclease Cas9, is a useful tool for genome editing [1,2,3]. Cas9 and sgRNA form a complex, which hybridizes with the target genomic sequence containing an NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) and subsequently creates a double-strand break (DSB) at the target site. This DSB is repaired by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), which is a mechanism prone to errors and introduces insertions and deletions (indels) at the DSB site. In an open reading frame, these indels can cause a frameshift mutation of the target gene. Additionally, mutated alleles with a large deletion can be generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system by designing a pair of sgRNAs targeting both ends of the target region. Therefore, this system can be used to generate genetically modified mice rapidly by microinjecting sgRNAs with Cas9 into fertilized eggs [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Several studies have reported the induction of an efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genomic rearrangement such as deletion or inversion of ~100 kb [10,11,12]. However, the maximum size of indels that can be induced by the CRISPR/Cas9 system is still unclear.

During our study on sexual differentiation, we set out to generate Irx3/Irx5 double mutant mice to analyze the phenotype in developing gonads because both genes are expressed in female but not in male developing gonads [13] and the gene products are functionally redundant [14, 15]. Previously, it has been reported that Irx3/Irx5 double knockout (dKO) mice generated by gene targeting using embryonic stem cells exhibited heart and early hindlimb bud defects and were embryonic lethal at 14.5 days post coitum (dpc); however, the gonadal phenotype was not described [14, 15]. Here, we have identified mutant mice with a 0.5 Mb deletion generated unintentionally in the course of Irx3/Irx5 dKO production by the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

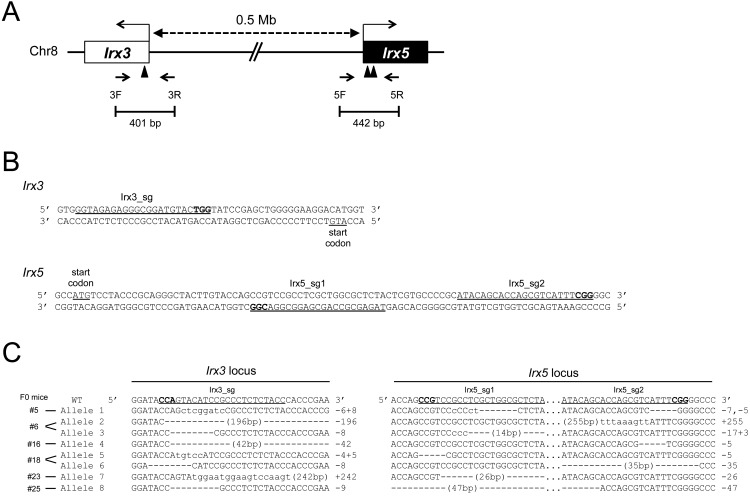

To elucidate the roles of the Irx3 and Irx5 genes in female gonadal development, we set out to generate double mutant mice using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. An online web tool was used to search for specific sgRNA sequences targeting the sequences around the start codons of Irx3 and Irx5. Specific sgRNAs, one for Irx3 (Irx3_sg) and two for Irx5 (Irx5_sg1 and 2), were identified (Fig. 1A and B). The efficiency of genome editing depends on the sgRNA sequence; therefore, all three sgRNAs were used along with the Cas9 mRNA for microinjection into 129 fertilized eggs to increase the probability of obtaining the desired mutant mice. Subsequently, 105 embryos were transferred into recipient mice at the two-cell stage. Finally, 27 founder pups survived. Analysis of the genomic DNA obtained from tail tips of these pups using primer-pairs of 3F/3R and 5F/5R showed that mutations (including biallelic, monoallelic, and mosaic) were observed in 92.6% (25/27) and 70.4% (19/27) of the mice at the Irx3 and Irx5 locus, respectively (Table 1). There was no mouse containing homozygous mutations in the Irx3 and Irx5 loci simultaneously, probably because Irx3/Irx5 dKO mice are embryonic lethal around 14.5 dpc [11]. These results showed that all designed sgRNAs efficiently induced DSBs at their respective target loci. Next, to obtain F1 mice with a mutation allele at both Irx3 and Irx5 loci (double mutant allele), ten F0 male mice were crossed with wild-type females. Genotyping analysis of F1 embryos obtained from the female mice showed that embryos obtained from 6 out of 10 founders contained mutations at both the Irx3 and Irx5 loci, suggesting that these six founders were carrying the double mutant allele. In total, eight independent double mutant alleles including four frame-shifted mutations were identified in 24% (21/89) of the embryos produced from the six founder mice (Table 2 and Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the microinjection-based method using the CRISPR/Cas9 system is effective for the production of double mutant mouse lines that have mutated genes located on the same chromosome and are functionally redundant.

Fig. 1.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated production of double mutant alleles at the Irx3 and Irx5 loci. (A) Schematic representation of the Irx3-Irx5 locus. A part of the genomic structure of the Irx3-Irx5 locus is shown. The white and black boxes represent exons of Irx3 and Irx5, respectively. The transcription start site of each gene is indicated with an arrow. Arrowheads indicate the locations of the target sites of sgRNA. The length between Irx3 and Irx5 is shown by a dotted line with arrows. Forward and reverse primers are indicated by red arrows. (B) sgRNA sequences targeting the Irx3 and Irx5 locus. The nucleotide sequence around the sgRNA targets for Irx3 (top) and Irx5 (bottom) are shown. The start codon and sgRNA target sequences are indicated with red letters. Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences are indicated with blue letters. (C) Irx3/Irx5 double mutant alleles obtained from F1 embryos. Each double mutant allele (Allele 1–8) was observed from six founder mice (shown with # and number). Hyphens and lowercase letters show deleted and inserted sequences, respectively. The numbers shown at right indicate the numbers of deleted (–) and inserted (+) nucleotides. sgRNA and PAM sequences are shown with underline and bold letters, respectively. Allele names are shown at the left.

Table 1. Generation of mutations in the Irx3-Irx5 locus of mice by the microinjection-based CRISPR/Cas9 system.

| sgRNA combination | Injected / two-cell | Transferred | Genotyped | Stage | Mutated at Irx3 | Mutated at Irx5 | 0.5 Mb deletion |

| Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1/Irx5_sg2 | 129 / 109 | 105 | 27 | Newborn | 25 (92.6) | 19 (70.4) | 6 (22.2) |

| Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1 | 138 / 132 | 108 | 24 | 13.5 dpc | 21 (87.5) | 19 (79.2) | 7 (29.2) |

| Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2 | 150 / 131 | 108 | 21 | 13.5 dpc | 20 (95.2) | 19 (90.5) | 3 (14.3) |

Numbers in parentheses represent the percentages calculated from the number of mutants relative to the number of genotyped embryos. sgRNA, single guide RNA; dpc, days post coitum.

Table 2. Production of F1 mice with double mutant alleles.

| F0 mice | No. of genotyped F1 |

No. of embryos mutated at Irx3 |

No. of embryos mutated at Irx5 |

No. of double mutant alleles |

Names of double mutant alleles |

| #3 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| #5 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2 | Allele 1 |

| #6 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 | Allele 2, 3 |

| #16 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | Allele 4 |

| #17 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| #18 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 5 | Allele 5, 6 |

| #19 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 0 | |

| #23 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | Allele 7 |

| #24 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| #25 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 1 | Allele 8 |

| Total | 89 | 40 | 54 | 21 | |

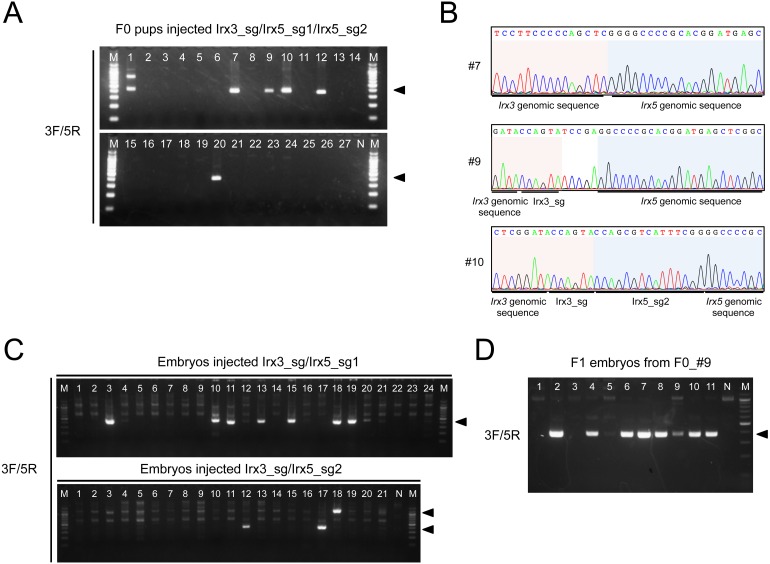

Irx3 and Irx5 are located on mouse chromosome 8 with ~0.5 Mb between them; therefore, a large genomic rearrangement (large deletion or inversion) could have occurred by the microinjection of the three sgRNAs with Cas9. To test this possibility, we performed genotyping analyses of the 27 pups using the 3F and 5R primers. A 400–500 bp fragment was detected in 6 out of 27 (22.2%) F0 pups (Fig. 2A). Sequencing these PCR products revealed that the DSB was located between the sequences targeted by Irx3_sg and Irx5_sg2 and the 557 kb deletion was identified (Fig. 2B). To examine whether microinjecting two sgRNAs but not three is sufficient to cause a large deletion, we generated embryos by microinjecting the Cas9 mRNA with pairs of sgRNAs, Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1 or Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2. Genotyping analysis using the primer-pairs 3F/3R and 5F/5R showed that 87.5% (21/24) and 79.2% (19/24) of the embryos injected with Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1 were mutated at the Irx3 and Irx5 locus, respectively, and 95.2% (20/21) and 90.5% (19/21) of the embryos injected Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2 were mutated at the Irx3 and Irx5 locus, respectively (Table 1). Genotyping analysis using the 3F and 5R primers revealed a large deletion in 29.2% (7/24) and 14.3% (3/21) of the embryos injected with Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1/Cas9 and Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2/Cas9, respectively, suggesting that microinjecting a pair of sgRNAs is sufficient to cause a large genomic deletion (Fig. 2C and Table 1). To examine whether or not the 0.5-Mb-deleted allele could be transmitted to the F1 generation, genotyping analysis for detection of 0.5-Mb-deletion allele was also carried out. F1 embryos were obtained by crossing F0 mice that possessed the deleted allele with wild-type mice. Some of the F0 mice with the 0.5 Mb deletion began to exhibit growth retardation at approximately 10 days after birth. This eventually became lethal when the mice were around 4 weeks old (Supplementary Fig. 1: online only), possibly due to skeletal and/or heart defects similar to those shown in Irx3/Irx5 compound heterozygous mutants [14]. F1 embryos were obtained by crossing an F0 mouse (F0_#9) with no such observed severe phenotypes and a wild-type mouse. The results obtained showed that a 0.5 Mb deletion occurred in 8 of 11 embryos (Fig. 2D), suggesting that a large deletion allele produced by this microinjection method could be transmitted to the F1 generation.

Fig. 2.

Detection of 0.5 Mb deletion in mutant mice. (A) Detection of the 0.5 Mb deletion in the genome of pups injected with Irx3_sg/Ix5_sg1/Irx5_sg2 with Cas9. Agarose gel electrophoresis image of PCR products amplified using 3F and 5R. Arrowheads indicate the position at which bands containing the amplified fragments appear. (B) Representative electropherograms of PCR fragment sequences. The genomic sequences of Irx3 and Irx5 are shaded in red and blue backgrounds, respectively. (C) Detection of the 0.5 Mb deletion in the genome of mouse embryos injected with Cas9 and Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1 or Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2, respectively. Agarose gel electrophoresis image of PCR products amplified using 3F and 5R. (D) Detection of the 0.5 Mb deletion in the F1 embryos obtained from mouse F0_#9. Arrowheads indicate the position at which bands containing the amplified fragments. N, no template control; M, 100 bp DNA ladder marker.

To detect a large inversion at the Irx3-Irx5 locus, genotyping analysis of the founder pups was conducted by PCR using the primer pairs 3F2/5F2 and 3R/5R (Supplementary Fig. 2A: online only). The fragment amplified using 3R/5R was detected in 14.8% (4/27) of the pups, whereas the fragment amplified using 3F2/5F2 was not detected in any of the pups (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Sequencing the fragments amplified using 3R/5R revealed that the fragment had an inverted orientation compared with that of the wild-type sequence at a DSB around the sgRNA target sequences (Supplementary Fig. 2C). These results indicate that NHEJ occurred at one DSB location between two fragments that were 0.5 Mb apart. Currently, we cannot explain what happened at the other DSB location. Genomic DNA extracted from embryos generated by microinjecting Cas9 with two sgRNAs was also analyzed. The results indicated that the fragment amplified using the 3F2/5F2 primers was detected in 29.2% (7/24) and 14.3% (3/21) of the embryos injected with Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1 and Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3A: online only). The fragment amplified using the 3R/5R primers was detected in 20.8% (5/24) and 28.6% (6/21) of the embryos injected with Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg1 and Irx3_sg/Irx5_sg2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3B). However, there was one embryo in which the fragments amplified using both primer pairs, 3F2/5F2 and 3R/5R, were detected, indicating that a 0.5 Mb inversion had occurred. We cannot explain what happened in the rest of embryos, which had only one detected fragment amplified using either primer set 3F2/5F2 or 3R/5R. Therefore, a 0.5 Mb inversion can be caused by microinjecting two sgRNAs and Cas9 into zygotes; however, its efficiency is low compared with that of a 0.5 Mb deletion.

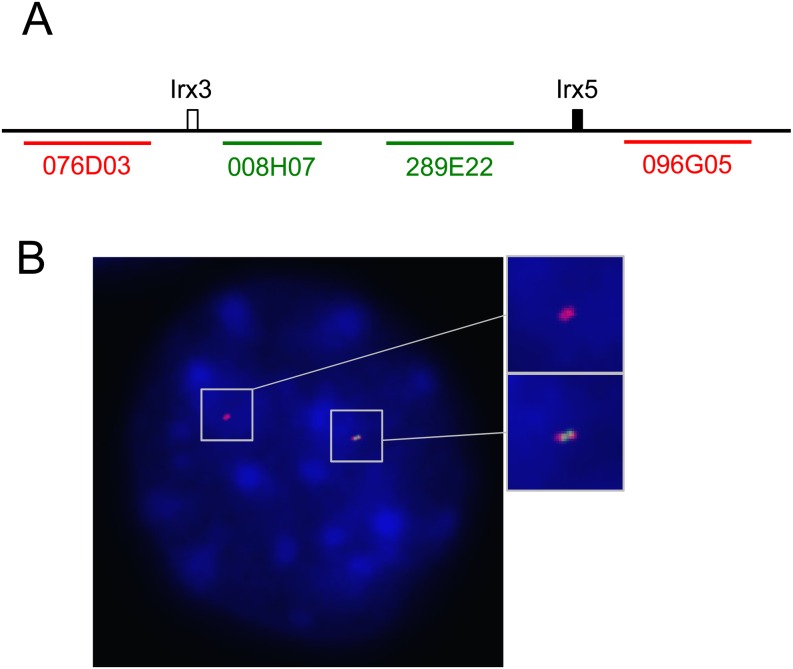

In order to confirm the deletion of the 0.5 Mb region, we carried out DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis using fibroblasts extracted from the tail tip of mutant pup #7 (see Figs. 2A and B). Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) harboring inside (B6Ng01-008H07 and B6Ng01-289E22) and outside (B6Ng01-076D03 and B6Ng01-096G05) the Irx3_sg and Irx5_sg1 sequences were used as probes (Fig. 3A). Two nucleic foci were observed in most cells; one showed signals from the probes that were inside and outside, and the other showed signals from only the outside probes (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the mutant pup #7 had a 0.5 Mb deletion allele.

Fig. 3.

DNA Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of tail tip fibroblasts derived from pup #7. (A) Schematic representation of the positions of BAC probes. BACs located outside of the Irx3-Irx5 locus are shown by red lines and letters. BACs located between Irx3 and Irx5 are indicated by green lines and letters. (B) An image showing fluorescently labeled fibroblast nuclei and probe foci by DNA FISH analysis. Signals were detected in red (B6Ng01-076D03 and B6Ng01-096G05) and green (B6Ng01-008H07 and B6Ng01-289E22) fluorescence, respectively. Blue signals are nuclear DAPI stains. Higher magnifications of areas indicated by boxes are shown at the right side.

This study demonstrated the efficient generation of double mutant mice via microinjection of a pair of sgRNA with Cas9 into zygotes, thereby indicating that the CRISPR/Cas9 system is useful for introducing mutations into two genes that are functionally redundant and whose deficiency leads to embryonic lethality. High efficiency of genome editing at the loci essential for embryonic development is assumed to cause lethality. However, in this study, 27 F0 pups were produced, all of which possessed the mutation at Irx3 and/or Irx5. Since a wild-type allele was identified in all mutants, it can be suggested that severe phenotypes derived from Irx3 and/or Irx5 deficiency were rescued by this mosaicism. [9, 16]

Mice with a large deletion were also observed, indicating that this method of using two sgRNAs and Cas9 has a possibility of producing a large deletion of at least 0.5 Mb at a given target locus. This type of side-reaction has been observed in previous studies [17,18,19]. Conversely, this also indicates that NHEJ-mediated concomitant mutagenesis of multiple genes located on the same chromosome is capable of producing F0 animals with large chromosomal rearrangements, rather than the induction of expected indels. Thus, it is important to consider the possibility that the animals possess mutations of large deletions/inversions as well as indels when phenotypes are analyzed in the F0 generation. In mice, mutation alleles can be isolated in the next generation. Nevertheless, PCR genotyping to detect large deletions/inversions should be performed in the F1 generation, since there is a risk that F1 littermates containing large deletions/inversions would be judged as wild-type if PCR genotyping is performed using a primer pair for the detection of indels only. Taken together, these results suggest that it is necessary to set up genotyping analyses not only for indels at the target loci but also for large chromosomal rearrangements such as deletions/inversions.

In conclusion, our findings expand the utility of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the production of disease model animals with multiple gene mutations or large deletions in their genome.

Methods

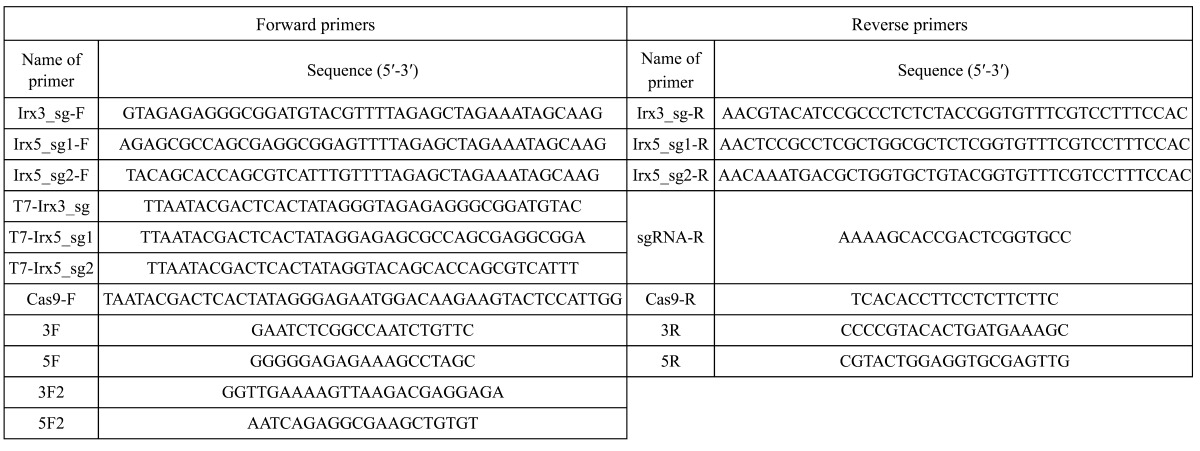

Preparation of sgRNAs and Cas9 mRNA

Human codon-optimized Cas9 (hCas9) and sgRNA cloning vector were gifted from George Church (Addgene plasmid #41815 and #41824, respectively) [3]. Specific sgRNA sequences were designed using the CRISPR Design Tool (http://genome-engineering.org/). sgRNAs for Irx3, Irx5, and Cas9 mRNA were prepared as previously described [20, 21]. Three sgRNA target sequences were cloned into sgRNA cloning vectors by inverse PCR using primers pairs Irx3_sg-F/Irx3_sg-R, Irx5_sg1-F/Irx5_sg1-R, and Irx5_sg2-F/Irx5_sg2-R (Table 1). In vitro transcription was performed using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Transcription Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). PCR products amplified using T7-added primers (T7-Irx3_sg for Irx3_sg, T7-Irx5_sg1 for Irx5_sg1, T7-Irx5_sg2 for Irx5_sg2, and Cas9-F and Cas9-R for Cas9 mRNA; Table 3 ) were used as templates. Transcribed RNAs were purified using the MEGAclear RNA Kit (Ambion).

Table 3. Primer sequences.

Microinjection

Superovulated F1 hybrid (C57BL/6 × DBA/2) BDF1 female mice were crossed with BDF1 male mice. The fertilized eggs were collected in M2 medium. Microinjection was carried out as previously described [21]. Embryos were cultured and transferred to pseudopregnant ICR female mice at the two-cell stage. All mice were obtained from the Sankyo Labo Service (Tokyo, Japan). All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan. All experiments were conducted in accordance with these approved animal protocols.

Genotyping and sequencing analysis

For genotyping analyses, genomic DNA was extracted from tail tips of F0 pups and embryos at 13.5 dpc. Genotypes were analyzed by PCR using KOD-FX neo (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan); primers are listed in Table 1. PCR products were analyzed by 1% (for 3F2/5F2 products) or 2.5% (for other products) agarose gel electrophoresis and treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and then sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA). For examination of germline transmission, F0 mice were crossed with C57BL/6N. F1 embryos at 9.5–11.5 dpc were obtained and genotyping analyses were carried out by PCR as described above. To determine the nucleotide sequence of mutated alleles, PCR products, amplified using the listed primers and phosphorylated by the T4 Kinase (Toyobo), were cloned into a HincII-digested pUC118 vector (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) and sequenced.

FISH analysis

Fibroblast cells were obtained from the tail tip of mutant mice. The tail tips were sequentially treated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 15 min and 0.1% collagenase for 15 min (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Biological Industries, Cromwell, CT, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 1 mM non-essential amino acids (Gibco), 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco), and 100 µM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cultured cells were then trypsinized to form a single cell suspension, which was subjected to hypotonic treatment with 0.5% KCl. Cells were fixed with 3:1 methanol:acetic acid and chromosome spreads were obtained by air-dry methods.

C57BL/6N mouse BAC clones were obtained from the RIKEN BRC through the National Bio-Resource Project of MEXT, Japan. BAC DNAs were extracted using NucleoBond BAC 100 (Takara Bio) and digested with EcoRI. The Probe DNAs were labeled by nick translation using the DIG (digoxigenin: for inside) or the BIO (biotin: for outside) -nick translation Mix (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). To denature the chromatin DNA, chromosome spreads were dipped in 70% formamide/2x SSC at 70°C. After dehydration in ethanol, hybridization was performed by incubating 10 µg/ml labeled probes in 50% formamide/2 × SSC containing 10% dextran sulfate, 2 mg/ml BSA, and 100 µg/ml COT human DNA (Roche) at 42°C overnight. After washing with 2 × SSC and 50% formamide/2 × SSC, digoxigenin and biotin were detected by 4 µg/ml FITC-conjugated anti-digoxigenin sheep polyclonal antibody (Roche) and 2 µg/ml Alexa 555-conjugated streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20. The ProLong Gold Antifade mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was then applied to the slides. Images were obtained using a Microscope Axio Imager A2 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a 600 × magnification.

Supplementary

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the Takada lab for helpful discussions and encouragement. This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Center for Child Health and Development, Grant Number 24-3 to ST.

References

- 1.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012; 337: 816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013; 339: 819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 2013; 339: 823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen B, Zhang J, Wu H, Wang J, Ma K, Li Z, Zhang X, Zhang P, Huang X. Generation of gene-modified mice via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting. Cell Res 2013; 23: 720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Qiu Z, Shao Y, Chen Y, Guan Y, Liu M, Li Y, Gao N, Wang L, Lu X, Zhao Y, Liu M. Heritable gene targeting in the mouse and rat using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31: 681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F, Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 2013; 153: 910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii W, Kawasaki K, Sugiura K, Naito K. Efficient generation of large-scale genome-modified mice using gRNA and CAS9 endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41: e187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mashiko D, Fujihara Y, Satouh Y, Miyata H, Isotani A, Ikawa M. Generation of mutant mice by pronuclear injection of circular plasmid expressing Cas9 and single guided RNA. Sci Rep 2013; 3: 3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen ST, Zhang M, Deng JM, Usman SJ, Smith CN, Parker-Thornburg J, Swinton PG, Martin JF, Behringer RR. Somatic mosaicism and allele complexity induced by CRISPR/Cas9 RNA injections in mouse zygotes. Dev Biol 2014; 393: 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Jia R, Palange NJ, Satheka AC, Togo J, An Y, Humphrey M, Ban L, Ji Y, Jin H, Feng X, Zheng Y. Large genomic fragment deletions and insertions in mouse using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0120396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Shao Y, Guan Y, Li L, Wu L, Chen F, Liu M, Chen H, Ma Y, Ma X, Liu M, Li D. Large genomic fragment deletion and functional gene cassette knock-in via Cas9 protein mediated genome editing in one-cell rodent embryos. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 17517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Shou J, Guo Y, Tang Y, Wu Y, Jia Z, Zhai Y, Chen Z, Xu Q, Wu Q. Efficient inversions and duplications of mammalian regulatory DNA elements and gene clusters by CRISPR/Cas9. J Mol Cell Biol 2015; 7: 284–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen JS, Gao L. Irx3 is differentially up-regulated in female gonads during sex determination. Gene Expr Patterns 2005; 5: 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Sakuma R, Vakili NA, Mo R, Puviindran V, Deimling S, Zhang X, Hopyan S, Hui CC. Formation of proximal and anterior limb skeleton requires early function of Irx3 and Irx5 and is negatively regulated by Shh signaling. Dev Cell 2014; 29: 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaborit N, Sakuma R, Wylie JN, Kim KH, Zhang SS, Hui CC, Bruneau BG. Cooperative and antagonistic roles for Irx3 and Irx5 in cardiac morphogenesis and postnatal physiology. Development 2012; 139: 4007–4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh BA, Beckman DL, Patel SJ, White JM, Yokoyama WM. Detailed phenotypic and molecular analyses of genetically modified mice generated by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0116484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizuno S, Takami K, Daitoku Y, Tanimoto Y, Dinh TT, Mizuno-Iijima S, Hasegawa Y, Takahashi S, Sugiyama F, Yagami K. Peri-implantation lethality in mice carrying megabase-scale deletion on 5qc3.3 is caused by Exoc1 null mutation. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 13632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boroviak K, Doe B, Banerjee R, Yang F, Bradley A. Chromosome engineering in zygotes with CRISPR/Cas9. Genesis 2016; 54: 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraft K, Geuer S, Will AJ, Chan WL, Paliou C, Borschiwer M, Harabula I, Wittler L, Franke M, Ibrahim DM, Kragesteen BK, Spielmann M, Mundlos S, Lupiáñez DG, Andrey G. Deletions, Inversions, Duplications: Engineering of Structural Variants using CRISPR/Cas in Mice. Cell Reports 2015; 5: 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inui M, Miyado M, Igarashi M, Tamano M, Kubo A, Yamashita S, Asahara H, Fukami M, Takada S. Rapid generation of mouse models with defined point mutations by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hara S, Tamano M, Yamashita S, Kato T, Saito T, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Inui M, Takada S. Generation of mutant mice via the CRISPR/Cas9 system using FokI-dCas9. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 11221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.