Abstract

We conclude that patients presenting with level 5 lymphadenopathy should be investigated with heightened clinical vigilance. Our results suggest that up to 80 % will harbour clinically significant pathology requiring further medical treatment, three quarters of which will be malignancy. We report an observational study of histological outcomes of level 5 lymph node biopsies from a regional histopathology department across 5 years. 184 subjects were identified as having a biopsy of a lymph node from the level 5 region within the study period. One hundred and fifty six cases (84.8 %) had clinically significant pathology on final histology requiring further medical treatment. Lymphoma accounted for the highest number of cases (n = 72, 39.1 %), followed by metastatic carcinoma (n = 65, 35.3 %) and granulomatous change (n = 17, 9.2 %). Gender and laterality were not shown to be independent predictors of pathology significance (p > 0.05).

Keywords: Neck lump, Malignancy, Lymphoma, Metastatic carcinoma, Histology

Introduction

Patients with persistent neck lumps are commonly referred to otolaryngologists from both primary and secondary care physicians. The obvious concern in the majority of cases is malignancy and the otolaryngologist is obliged to investigate based upon the clinical presentation and risk factors in each individual case. After conducting a thorough clinical examination, serological, radiological and histological investigations are carried out as necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Clinical features of particular concern include: large size, a firm, rubbery or hard consistency, skin ulceration or fixation or if the node lies in a supraclavicular position [1, 2].

Commonly, fine needle aspiration for cytology (FNAC) is performed in the outpatient setting as the initial ‘biopsy’ [3]. This can be performed with or without ultrasound guidance depending on whether the lump is easily palpable, or depending upon the risk of damage to surrounding structures. Where FNAC is unable to give a definitive diagnosis, core or excision biopsy is undertaken for formal histology to guide further management of the patient.

Anatomically, level 5 of the neck is also referred to as the posterior triangle. Its boundaries are the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid anteriorly, the anterior border of trapezius posteriorly and the superior border of the clavicle inferiorly. The lymph nodes contained within level 5 of the neck include the supraclavicular nodes [4]. It is known that occipital and mastoid, lateral neck, scalp, nasal pharyngeal regions drain to level 5 nodes. Large level 5 nodes may contain metastases from nasopharyngeal and thyroid primary malignancies [4]. The pattern of lymph node drainage in the head and neck to other levels in the neck relative to the most commonly diagnosed primary sites of malignancy have been previously acknowledged in the literature [5].

There are few previous publications limited specifically to level 5 and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. We present our experiences from a five year review of the histology results of patients presenting with level 5 neck masses to inform current clinical practice.

Method

We conducted a retrospective review of reports obtained at a regional histopathology department for level 5, posterior triangle and supraclavicular lymph nodes during the period between November 2009 and October 2014. Only cases where the clinical history entered by the requesting clinician explicitly mentioned the site of lymph node being “level 5”, “posterior triangle” or “supraclavicular” were included for analysis. A total of 252 cases were reviewed. Where there was insufficient specimen obtained for a diagnosis, or where the lymph node sampled was part of a neck dissection, these cases were excluded. This yielded a total of 184 cases for final analysis. Statistical calculations were made using GraphPad Prism software version 5. Cases where laterality was not recorded were excluded from data analysis against laterality. Where full year data was available between 2010 and 2013, pathological outcome was reviewed to examine for regional trend in diagnoses.

Results

The age range was 4–96 years, with a median age of 62 years. Six of our patients were aged less than 18 years (3.3 %), all were male, the remainder were “adult” (19–96). The male:female ratio was 88:96. Laterality was not included in the report for 6 cases. The majority of patients presented with a left sided neck mass (n = 101, 56.7 %).

Excision biopsy was the most common method of obtaining tissue (n = 132, 71.7 %), but our series also included core biopsies (n = 45, 24.5 %) and fine needle aspiration biopsies (n = 7, 3.8 %). The majority of clinicians labelled their forms as a supraclavicular mass (n = 128, 69.6 %), compared to posterior triangle (n = 20, 10.9 %) or level 5 (n = 36, 19.6 %).

Clinically significant pathology was classed as a condition where further medical treatment was required. This included malignancy (solid organ, mucosal and haematological), granulomatous change (sarcoid, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis), cystic inflammation and amyloidosis. Non-significant change was defined as reactive follicular hyperplasia only.

Overall, 156 cases (84.8 %) showed evidence of clinically significant pathology. The most common significant pathology identified was lymphoma (n = 72, 39.1 %, Fig. 1). Metastatic carcinoma accounted for 35.3 % (n = 65, Fig. 1), and granulomatous change 9.2 % (n = 17). Histology identified a single case of inflamed cystic change and 1 case of amyloidosis infiltrating the lymph node. Results relative to patient age, type of biopsy and side of presenting node are presented in tabulated (Table 1) and graphical forms (Figs. 2, 3).

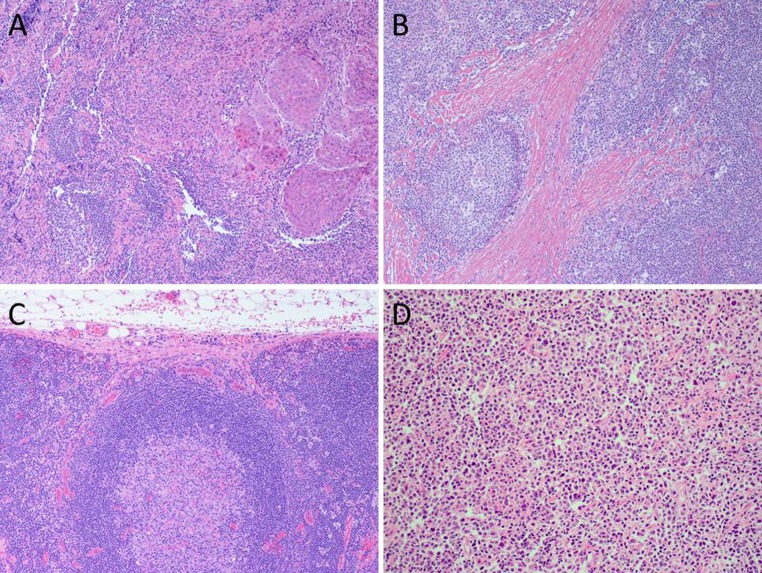

Fig. 1.

a Lymph node metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma. Malignant cells with ample cytoplasm and evidence of keratinisation on the left. Note background lymph node on the right. b Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Note the dense and eosinophilic fibrosis with characteristic mono-bi-nucleated Hodgkin’s cells. c Reactive lymph node. Note nodal capsule (top), subcapsular sinus and cortex where a large follicle with germinal centre is seen. d Diffuse large B cell lymphoma. The lymph node is replaced by pleomorphic cells with vesicular nuclei and visible nucleoli. The cells show positive staining for me cell markers

Table 1.

Summary of histological diagnosis and patient factors

| Pathology | Age | Gender | Laterality | Type of biopsy | Year of diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4–18 years | ≥19 years | Male | Female | Left | Right | Excision | Core | FNA | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Lymphoma | 3 | 69 | 33 | 39 | 40 | 31 | 65 | 7 | 18 | 14 | 9 | 12 | |

| Carcinoma | 65 | 32 | 33 | 36 | 25 | 25 | 34 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 6 | 15 | |

| Granulomatous | 17 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | |

| Amyloid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Inflamed cyst | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Subtotal | 3 | 153 | 74 | 82 | 87 | 64 | 107 | 42 | 7 | 29 | 31 | 18 | 34 |

| Reactive | 3 | 25 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 25 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | |

| Subtotal | 3 | 25 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Total | 184 | 184 | 178 | 184 | 133 | ||||||||

| p value | 0.0463 | 0.8395 | 0.6743 | 0.0734 | 0.5052 | ||||||||

| Test | Fisher’s exact | Fisher’s exact | Fisher’s exact | Chi-square | Chi-square | ||||||||

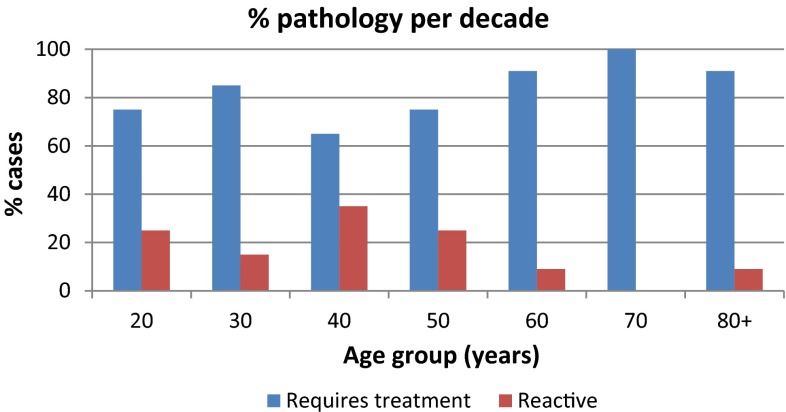

Fig. 2.

Percentage of pathological versus reactive level 5 lymphadenopathy

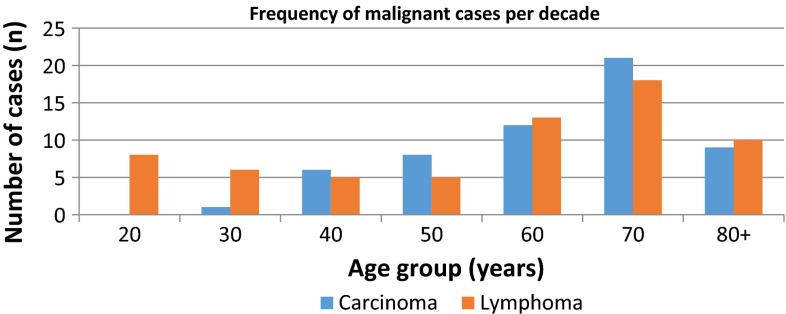

Fig. 3.

Distribution of malignant pathology per decade of age

Gender, laterality of the presenting neck mass and biopsy type were not shown to be clinically significant (p > 0.05) against the final pathology. On Fisher’s exact test, age group barely reached clinical significance with a calculated p value of 0.0463.

Discussion

Of 184 cases of level 5 lymph node biopsy performed over a 5 years period in our region, where a histological diagnosis was sought due to clinical suspicion, 84.8 % had clinically significant pathology requiring further treatment. Three in four histological analyses resulted in a diagnosis of malignancy. Lymphoma was the most frequent.

There are no studies looking at the final histology of nodes purely within the area defined as level 5 of the neck. There have, however, been studies reviewing biopsies of nodes in the ‘supraclavicular’ region, particularly regarding the diagnostic yield of FNAC. Such studies have found malignancy rates of between 55 and 71 %, with a higher lymphoma:metastatic carcinoma ratio in subjects younger than 40 when compared to those above 40 years [6–10]. In one of these studies, the actual malignancy rate was found to be as high as 86.5 % (n = 45) on final histology of excisional biopsy [7]. This was not a primary outcome of their article, as the purpose of this particular study was to report on the diagnostic accuracy of FNAC. Nevertheless, this figure supports our findings of a higher malignancy rate for nodes from this anatomical region. This study also showed a slight preponderance of malignancy found in left sided nodes [7]. However, our study, and a previously reported series of 309 patients, did not [8]. In published studies looking particularly at cervical lymphadenopathy in children, the supraclavicular site has been found to be more frequently associated with malignancy than lymph nodes elsewhere [1, 11, 12]. The frequency of malignancy against age observed within our study reflects that of other reported figures in terms of the bimodal age distribution in newly diagnosed lymphomas [13] and the correlation between incidence of metastatic carcinoma with rising age.

Although FNAC is a well-established first diagnostic tool for the evaluation of lymph nodes [3], only core biopsy or excision biopsy will be sufficient for the formal diagnosis of lymphoma when further analytical techniques are unavailable, such as immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and specific stains [9, 14–16]. The British Society of Pathologists recommend whole node specimens where possible due to the volume of tissue required for testing to secure a diagnosis [16]. This explains the volume of excision biopsies carried out in our series, and may also explain the tendency of FNAC studies to report higher rates of metastatic carcinoma over haematological malignancy.

Core biopsy carries an additional risk of mucosal tumour seeding [16, 17] and therefore, when in doubt, and when a conclusive procedure is required, excision biopsy may be the best option. Although lymph node biopsy carries a specific risk of accessory nerve damage when undertaken within the posterior triangle [18, 19], this risk is extremely low, and the procedure can be carried out safely and easily under local anaesthetic in the right hands.

This is an observational study based on the patient demographics and final pathology reports available to us. The quality of the clinician requests therefore has impacted on the number of patients we could include in our series. There was no statistical power calculation performed beforehand, and therefore the implications of the P values calculated are limited. However, our observations over the past 5 years add valuable evidence to the currently available literature supporting the notion that lymphadenopathy in the level 5 region of the neck is more likely to harbour a significant pathological process, frequently malignant, that may require further treatment.

Based on our findings, and after review of the relevant literature, where clinical suspicion leads a clinician to formally biopsy a level 5 cervical lymph node, there is a 4 in 5 chance of clinically significant pathology requiring further treatment with 3 in 4 demonstrating malignancy.

References

- 1.Nolder AR. Paediatric cervical lymphadenopathy: when to biopsy? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21(6):567–570. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2103–2110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta RK, Naran S, Lallu S, Fauck R. The diagnostic value of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the assessment of palpable supraclavicular lymph nodes: a study of 218 cases. Cytopathology. 2003;14:201–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2003.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins K, Shaha AR, Medina JE, et al. Consensus statement on the classification and terminology of neck dissection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(5):536–538. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genden E, Varvares M, editors. Head and neck cancer: an evidence-based team approach. New York: Thieme publishers; 2011. pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candela FC, Kothari K, Shah JP. Patterns of cervical node metastases from squamous carcinoma of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. Head Neck. 1990;12:197–203. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHenry CR, Cooney MM, Slusarczyk SJ, Khiyami A. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy: the spectrum of pathology and evaluation by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Am Surg. 1999;65(8):742–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison E, LaPuerta P, Martin SE. Supraclavicular masses: results of a series of 309 cases biopsied by fine needle aspiration. Head Neck. 1999;21(3):239–246. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199905)21:3<239::AID-HED9>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasuti JF, Mehrotra R, Gupta PK. Diagnostic value of fine-needle aspiration in supraclavicular lymphadenopathy: a study of 106 patients and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25(6):351–355. doi: 10.1002/dc.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cervin JR, Silverman JF, Loggie BW, Geisinger KR. Virchow’s node revisited. Analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 152 fine-needle aspiration biopsies of supraclavicular lymph nodes. Arch Path Lab Med. 1995;119(8):727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingolfsdottir M, Balle V, Hahn CH. Evaluation of cervical lymphadenopathy in children: advantages and drawbacks of diagnostic methods. Dan Med J. 2013;60(8):A4667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oguz A, Karadeniz C, Temel EA, Citak EC, Okur FV. Evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Haematol Oncol. 2006;23(7):549–561. doi: 10.1080/08880010600856907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Haematological malignancies cancer registration in England (2004–2008). Quality appraisal comparing data from the National Cancer Data Repository (NCDR) with the population-based Haematological Malignancy Research Network (HMRN). Final Report. London: Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research; 2012.

- 14.Herd MK, Woods M, Anand R, Habib A, Brennan PA. Lymphoma presenting in the neck: current concepts in diagnosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(4):309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.03.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen OM, Aarstad HJ, Løkeland T, Bostad L. Diagnostic yield of biopsies of cervical lymph nodes using a large (14-gauge) core biopsy needle. APMIS. 2013;121:1119–1130. doi: 10.1111/apm.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Best practice in lymphoma diagnosis and reporting. Royal College of Pathologists. London 2010. http://www.bcshguidelines.com/documents/Lymphoma_diagnosis_bcsh_042010.pdf.

- 17.Robertson EG, Baxter G. Tumour seeding following percutaneous needle biopsy: the real story! Clin Radiol. 2011;66(11):1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung L, McCombe A. The diagnostic yield of cervical lymph node excision biopsy presenting via the head and neck ‘lump-and-bump’ clinic. Clin Otolaryngol. 2014;39:133. doi: 10.1111/coa.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Battista AF. Complications of biopsy of the cervical lymph node. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;173:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]