In the U.S., as of 2012, more than one in three youth were overweight or obese [1]. This is a critical health issue, as being overweight or obese (OW/OB) during adolescence increases the risk of adulthood diseases, including but not limited to cardiovascular and heart disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer, and osteoarthritis [2]. Understanding the pathways to obesity is critical for implementation of successful prevention and intervention programs. One of the pathways leading to OW/OB is through social and economic experiences within the family.

One critical factor associated with the family may be the parenting behaviors adolescents’ experience. Specifically, research [3, 4, 5, 6] has found that authoritarian or harsh parenting styles (e.g., strict, physical, and/or controlling) increased the propensity toward obesity during childhood. Moreover, some studies show that the prevalence of harsh parenting may be stronger for girls [7, 8], while others show that it is similar for families of boys and girls [9]. However, literature to date has yet to explore whether parenting experienced during adolescence leads to OW/OB into adulthood, prospectively by gender. Indeed, experiencing harsh parenting (HP) may set off a stress response in youth predisposing them to OW/OB. Experiencing stress may also contribute to negative behavioral responses, such as poor eating habits [10] and reduced physical activity [11], which may then contribute to OW/OB [12, 13].

In addition to HP, familial economic experiences have also been shown to predict childhood OW/OB. Specifically, food insecurity (FI, e.g., not having the financial means to access enough food to sustain healthy, active living for all members of the household; [14]) is a serious issue for 8.3 million children in the U.S. Some studies have found a positive relationship between FI and OW/OB [15, 16]. For example, Mohammadi et al. [15] and Pan et al. [16] found that FI was associated with adult obesity. Interestingly, others have shown food insecure women had a higher BMI than food secure women, but this relationship was not present in men [17, 18]. In a recent meta-analysis, results show that FI and obesity were strongly and positively associated [19]. However, others have found an inverse relationship [20] or no relationship [21, 22]. Moreover, similar to the long-term influences of parenting, studies have yet to explore if FI experienced during adolescence leads to OW/OB into adulthood.

Finally, studies have explored how FI may moderate the association between stressful experiences, such as exposure to HP, and obesity [23]. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the relation and interaction between HP and FI in adolescence (age 13 years) on the development of OW/OB in emerging adulthood, age 23 years. We also examined differences in these associations by gender, as few have done so [24, 25]. We hypothesized experiencing HP in adolescence, in conjunction with FI, will increase the odds of developing OW/OB for females [26] in emerging adulthood.

This study is innovative in many ways. First, it uses prospective longitudinal data [26]. Second, this study used measures of observed HP from both mothers and fathers of the adolescent, as opposed to self-reported parenting behaviors of one parent, typically the mother. Third, previous work has only considered FI at one time point; this study considers FI across four years during adolescence. Finally, this is the first study to examine if exposure to FI and HP during adolescence has long-term effects into emerging adulthood.

METHODS

Sample

Data came from the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP), a longitudinal study of 451 adolescent youth and their family members beginning in 1989 in the rural Midwest. In the first wave, adolescents were 13 years old, father’s average age was 40 and mother’s average age was 38. The sample is predominantly White (99%). This study examined youth who participated from adolescence into adulthood 1989 to 1999 (n=362). This project has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Iowa State University.

Procedure

Families were visited in their homes by trained interviewers, wherein each family member completed questionnaires. In addition, the families participated in videotaped interaction tasks where they discussed topics such as family rules, events, and problems, for 30 minutes. These behaviors were coded by trained observers using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales [27, 28].

Measures

Emerging Adult Overweight/Obesity

Being OW/OB was assessed through self-report height and weight in 1999 at age 23 years. Body mass index (BMI) and CDC weight classifications were calculated based on the Centers for Disease Control formulas [29]. Those with a BMI of 25 or above were coded as (1) OW/OB; those with a BMI of 24 or below were coded as (0) healthy. Underweight participants were excluded from the analyses so we could compare OW/OB individuals to healthy individuals [22].

Harsh Parenting

Observer ratings were used to assess mother and father HP toward the 13-year old adolescent in 1989 [27, 28]. HP consisted of three behaviors: (1) physical attack (hostile or aversive physical contact,); (2) harsh discipline (punishment in response to misbehavior); and (3) hostility (angry, critical, or disapproving behavior). Each behavior was coded from (1) not at all characteristic to (5) highly characteristic. The mother and father behavioral measures were averaged. (α = .59).

Food Insecurity

FI was assessed through mother and father report when the adolescent was 13 to 16 years old. This construct consisted of two items [30] which align with the 18-item Core Food Security Module (CFSM) used by the USDA in the calculation of official FI rates in the United States [31]. These items have similar response patterns in multiple data sets including the 2004 Current Population Survey [32]. The first question asked if each parent had enough money to afford the food he/she should have (1=strongly agree to 5=strongly disagree). This item was recoded to (1) yes, more food insecure and (0) no, less food insecure. The second item asked if the parent had changed food shopping or eating habits to save money; (1) yes or (0) no. Both mother and father reports from all four waves (1989-1992) were averaged to create one FI variable which ranged from (0) no FI to (2) FI (α = .83).

Gender

Adolescent gender was coded as (0) female and (1) male.

Respondent Education Level

Since education has been related with adult weight status [33], we controlled for the adolescent’s highest level of education completed at age 23 which ranged from 9th grade to a master’s degree/additional schooling.

Family of Origin per Capita Income

Total annual household income in the past 12 months (1988 dollars) was divided by the number of people in the household in 1989, representing the amount of financial resources available for each member of the family.

Parent Education Level

Both mother and father reported their highest level of education completed in 1989, which ranged from 9th grade to a master’s degree/additional schooling. Both mother and father variables were combined and averaged to create one manifest variable.

Adolescent & Parent BMI

Adolescent BMI was as assessed through self-reported height and weight in 1989 at age 13 years old, while parent BMI was assessed through mother and father self-report in 1992 when the adolescent was 16 years old. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard CDC formula [29].

RESULTS

A series of logistic regressions were used to predict OW/OB in emerging adulthood (see Table 2). Model 1, which examined direct effects of the independent variables and covariates, revealed a higher level of HP in adolescence predicted greater odds of OW/OB in adulthood. In other words, for each increase in level of harsh parenting the adolescent experienced, the adolescent was 31% more likely to be OW/OB in emerging adulthood. Males were 70% more likely to be OW/OB than females. A higher level of parental education in adolescence lowered the odds of OW/OB during emerging adulthood by 35%. The adolescent’s BMI at age 13 and father’s BMI positively predicted OW/OB at 23 years. In other words, those adolescents who had a higher BMI at age 13 as well as those adolescents whose fathers had a higher BMI were more likely to be OW/OB at 23 years.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression: Predicting Overweight/Obesity in Emerging Adulthood

| Model 1 | CI at 95% | Model 2 | CI at 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harsh Parenting | 1.31* (0.14) | 1.00 – 2.20 | 1.47* (0.15) | 1.10 – 1.97 |

| Food Insecurity | 0.79 (0.15) | 0.59 – 1.05 | 0.82 (0.16) | 0.61 – 1.12 |

| Gender, Male = 1 | 1.70*** (0.13) | 1.30 – 2.02 | 1.80*** (0.14) | 1.34 – 2.36 |

| Covariates3 | ||||

| Adolescent BMI | 4.08*** (0.20) | 2.77 – 6.00 | 4.32*** (0.20) | 2.89 – 6.44 |

| Education Level in Emerging Adulthood | 1.13 (0.14) | 0.86 – 1.49 | 1.14 (0.14) | 0.86 – 1.52 |

| Parent Per Capita Income | 0.91 (0.15) | 0.68 – 1.21 | 0.92 (0.15) | 0.69 – 1.24 |

| Parent Education Level | 0.65** (0.16) | 0.48 – 0.88 | 0.64** (0.16) | 0.46 – 0.87 |

| Mother BMI | 1.25 (0.15) | 0.92 – 1.68 | 1.21 (0.15) | 0.89 – 1.64 |

| Father BMI | 1.45* (0.15) | 1.08 – 1.94 | 1.56** (0.16) | 1.15 – 2.11 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Gender × Harsh Parenting | 0.83 (0.15) | 0.62 – 1.10 | ||

| Gender × Food Insecurity | 0.98 (0.15) | 0.74 – 1.31 | ||

| Harsh Parenting × Food Insecurity | 1.20 (0.15) | 0.89 – 1.63 | ||

| Gender × Harsh Parenting × Food Insecurity | 0.64** (0.15) | 0.47 – 0.85 | ||

Notes: (1)

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

(2) Odds ratios are reported with standard errors in parentheses.

All covariates are measured when the adolescent was 13 years, except for emerging adulthood education which was measured concurrently with the dependent variable at age 23 years and parental BMI which was measured when the adolescent was 16 years old.

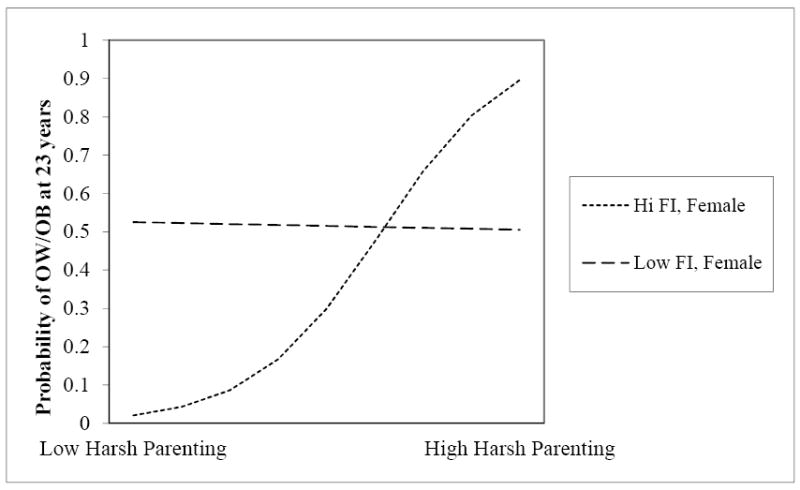

For parsimony, the final model testing a three-way interaction is shown in Table 2. A statistically significant three-way interaction was found between FI, HP, and gender. As shown in Figure 1, this association was statistically significant for females but not males. Specifically, for females who experience high levels of FI in adolescence, the odds of OW/OB are low when levels of HP are low; in contrast, a combination of high levels of HP and high levels of FI dramatically increased the odds of OW/OB in emerging adulthood. In other words, those females who experienced only food insecurity but not harsh parenting in adolescence were not at risk of OW/OB in emerging adulthood. But, those who experienced both food insecurity and harsh parenting were at a significantly high risk of developing OW/OB.

Figure 1.

Interaction between harsh parenting, food insecurity, and gender predicting Overweight/Obesity during Emerging Adulthood

Additional analyses were conducted in order to solidify the associations revealed above. To test if our results were driven by concurrent or longitudinal associations between food insecurity and OW/OB, we analyzed a model that also included concurrent food insecurity during emerging adulthood or at the same assessment time period of the outcome variable. The inclusion of concurrent food insecurity during emerging adulthood was not significantly associated with OW/OB in adulthood, nor did it negate the statistically significant influence of food insecurity during adolescence on OW/OB in emerging adulthood. To further test the endogeniety of these relationships, we stratified our analyses by the adolescent’s weight category, to ensure that it was not just those who were already OW/OB in adolescence that were driving the significant results in emerging adulthood. Results showed that the significant association between food insecurity in adolescence and emerging adult OW/OB was found for both groups – adolescents who were healthy weight and those who were already OW/OB in adolescence. The same holds true for the interaction results tested in Model 2. Finally, attrition analyses were conducted to see if adolescents assessed in the present analysis varied on key behaviors and family characteristics compared to those respondents who were not retained in the longitudinal survey. Overall, the adolescents did not vary on key socioeconomic profiles, showing that the sample utilized in the present sample is representative of the overall project.

DISCUSSION

The Effect of Harsh Parenting, Food Insecurity, and Gender on OW/OB in Emerging Adulthood

The results show that HP experienced during adolescence increased the odds of OW/OB in adulthood, but, consistent with previous research [i.e. 32], FI by itself did not. However, when these constructs were examined in combination, our hypothesis was supported. For females, experiencing FI amplified the influence of HP on the development of OW/OB in emerging adulthood, but not for males. Since those who experience FI but not HP have a lower risk of developing OW/OB, this may suggest positive parenting behaviors act as a buffer against the development of OW/OB in food-insecure households. Notably, our hypothesis was supported even after controlling for mother and father BMI. Indeed, the risk and development of OW/OB is highly heritable – as much as 70% [34]. Overall, the results provide support for the idea that social and economic experiences in the family impact the development of OW/OB differently for males and females, above and beyond any potential inherited predispositions toward OW/OB.

Gender Differences

It is important to note why FI, in the presence of HP, might influence obesity in females but not in males. Some have suggested this may be the result of differential perceptions and behaviors surrounding FI. Specifically, women may be more likely to report FI than men, or they are more likely to forego their own allocation of food in order to give it to their child [35]. It may also be that women are more likely to be heads of households with children and as a result would have to share their food resources with more people, compared to males [35]. However, in this study, FI was measured from both mother’s and father’s report; in addition, it represented FI across four waves, at four different time points. This represents a more accurate picture of long-term FI, compared to measuring FI at one point in time. Thus, differential perceptions and behaviors surrounding FI may not fully explain the gender difference we found. It may also be due to basic biological differences between the sexes. For example, Power and Schulkin [36] suggest men and women have different pathways to obesity, likely due to different metabolic functioning [37]. Female brains are more sensitive to levels of leptin, while male brains are more sensitive to levels of insulin [38]. In addition, men and women deposit, carry, and utilize fat differently [36]. The differential patterns of adiposity and metabolic functioning may have evolved in humans because of asymmetrical reproductive demands of males and females [36].

Limitations

There are limitations to this study that should be addressed. First, BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight of the adolescent, mother, and father. This should not significantly hinder the results, as individuals who are obese tend to underestimate their height and weight [39]. Second, the earliest age at which parents reported their height and weight was when the adolescent was 16 years old; thus, this was the time point at which we could control for mother and father BMI, not at 13 years. This is still beneficial, as adult BMI tends to be consistent over a 7-year period [40] and those who are obese earlier in life tend to also be obese later in life [41,42]. Third, research in this area could benefit from mixed-methods approaches that include qualitative investigations to explore the directions of these relationships. Finally, the sample was limited in terms of ethnic and racial diversity, as well as geographic location. Future research using more diverse samples is needed. However, models of stress and parenting with this sample have been extended to other studies using diverse ethnic samples [43].

CONCLUSION

This study contributes to an understanding of the interplay between social and economic circumstances in the family, and the differential development of OW/OB in males and females in emerging adulthood. More broadly, this study contributes to an understanding of the probable stress response activated as a result of HP, and provides a nuanced understanding of how this stress response behaves in the presence of cumulative FI for males and females. This research is especially advantageous in understanding the differential pathways to OW/OB from adolescence to adulthood. Finally, the results argue for preventive measures such as increasing women’s access to food during children’s key developmental periods such as early adolescence, not just the early years. And, secondly, educating parents about the long-term harmful influence of harsh parenting on kid’s physical health. Addressing both of these family factors could help reduce the long-term implications for emerging adults’ health, particularly BMI in girls.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (n=362)

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome, Age 23 years | |||

| Overweight/Obesity in Emerging | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0 – 1 |

| Adulthood | |||

| Early Adolescent Predictors | |||

| Harsh Parenting | 1.71 | 0.45 | 1 – 3.17 |

| Food Insecurity | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0 – 1.88 |

| Covariates | |||

| Gender, Male = 1 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0 – 1 |

| Adolescent BMI | 20.19 | 3.39 | 10.09 – 34.43 |

| Respondent Education Level | 14.72 | 1.67 | 9 – 19 |

| Per Capita Income (in dollars) | 7933 | 5003 | -10245 – 28750 |

| Parent Education Level | 13.42 | 1.61 | 9 – 19 |

| Mother BMI | 26.66 | 5.73 | 18.50 – 0.00 |

| Father BMI | 27.90 | 4.12 | 18.50 – 43.00 |

Note: All control variables were assessed when the adolescent was age 13, except for education level of the respondent and parent BMI which were assessed when the adolescent was age 23 years in emerging adulthood.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Assessing antecedents to overweight/obesity via parental and economic pathways provides policy makers and practitioners with a more holistic view of the ways in which adolescents turn into overweight/obese adults. Such information can be useful for reducing obesity rates in adolescence and emerging adulthood

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (HD064687, HD051746, MH051361, and HD047573). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, and MH48165), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings. This research is also supported by an Iowa State University College of Human Sciences Small Grant as well as an U.S.D.A. Hatch Projects Grant, IOW03816.

A special thank you is extended to the children, caregivers, and families who have graciously participated in this study and given us access to their lives for so many years.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vollmer RL, Mobley AR. Parenting styles, feeding styles, and their influence on child obesogenic behaviors and body weight. A review. Appetite. 2013;71:232–41. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murashima M, Hoerr SL, Hughes SO, Kattelmann KK, Phillips BW. Maternal parenting behaviors during childhood relate to weight status and fruit and vegetable intake of college students. J Nutr Behav. 2012;44(6):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee KE, Lumeng JC, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Bradley RH. Parenting styles and overweight status in first grade. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2047–2054. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berge JM, Wall M, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parenting style as a predictor of adolescent weight and weight-related behaviors. JAH. 2010;46(4):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnette ML, Oshri A, Lax R, Richards D, Ragbeer S. Pathways from harsh parenting to adolescent antisocial behavior: A multidomain test of gender moderation. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(3):857–870. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000417. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taillieu TL, Afifi TO, Mota N, Keyes KM, Sareen J. Age, sex, and racial differences in harsh physical punishment: Results from a nationally representative United States sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(12):1885–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barajas-Gonzalez RG, Brooks-Gunn J. Income, neighborhood stressors, and harsh parenting: Test of moderation by ethnicity, age, and gender. J of Fam Psych. 2014;28(6):855–866. doi: 10.1037/a0038242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicklas TA, Yang S, Baranowski T, et al. Eating patterns and obesity in children – The Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:9–16. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, et al. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: Predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Ado Health. 2006;39:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robila M, Krishnakumar A. Economic pressure and adolescents’ psychological functioning. J Child Fam Stud. 2006;15:435–443. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9053-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overview. USDA Economic Research Service website. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us.aspx#.U1SDG9yGsds.

- 14.Mohammadi F, Omidvar N, Harrison GG. Is household food insecurity associated with overweight/obesity in women? Iranian J Pub Health. 2013;42(4):380–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan L, Sherry B, Njai R, Blanck HM. Food insecurity is associated with obesity among US adults in 12 states. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(9):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin MA, Lippert AM. Feeding her children, but risking her health: The intersection of gender, household food insecurity and obesity. Soc Sc Med. 2012;74:1754–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gooding HC, Walls CE, Richmond TK. Food insecurity and increased BMI in young adult women. Obesity. 2012;20(9):1896–1901. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franklin B, Jones A, Love D, Puckett S, Macklin J, White-Means S. Exploring mediators of food insecurity and obesity: A review of recent literature. J Com Health. 2012;37(1):253–264. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9420-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose D, Bodor J. Household food insecurity and overweight status in young school adolescents: results from the early adolescent longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:464–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gundersen C, Lohman B, Eisenmann J, Garasky S, Stewart S. Lack of association between adolescent-specific food insecurity and overweight in a sample of 10–15 year old low-income youth. J Nutr. 2008;138:371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhargava A, Jolliffe D, Howard L. Socioeconomic, behavioral and environmental factors predicted body weights and household food insecurity scores in the Early Adolescent Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:438–4. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508894366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohman BJ, Stewart S, Gundersen C, Garasky S, Eisenmann JC. Adolescent overweight and obesity: links to food insecurity and individual, maternal, and family stressors. J Ado Health. 2009;45(3):230–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wardle J, Waller J, Jarvis MJ. Sex differences in the association of socioeconomic status with obesity. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(8):1299–1304. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.8.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanter R, Caballero B. Global gender disparities in obesity: A review. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(4):491–8. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin KS, Ferris AM. Food insecurity and gender are risk factors for obesity. J Nutr Educ Beh. 2007;39(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenmann JC, Gundersen CG, Lohman BJ, Garasky S, Stewart SD. Is food insecurity related to overweight and obesity in children and adolescents? A summary of studies 1995 – 2009. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(501):e73–e83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melby J, Conger R, Book R, et al. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. 5. Ames, IA: Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa family interaction rating scales: Instrument summary. Family Obs Coding Sys. 2001:33–58. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Healthy Weight – it’s not a diet, it’s a lifestyle! Centers for disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted.

- 30.Pearlin L, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(2):337–356. doi: 10.2307/2136676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nord M, Hopwood H. Recent advances provide improved tools for measuring children’s food security. J Nutr. 2007;137(3):533–536. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gundersen C, Lohman BJ, Eisenmann J, Garasky S, Stewart S. Child-specific food insecurity and overweight are not associated in a sample off 10–15 year old low-income youth. J Nutr. 2008;138:371–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen AK, Rai M, Rehkopf DH. Educational attainment and obesity: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2013;14(12):989–1005. doi: 10.1111/obr.12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrera BM, Keildson S, Lindgren CM. Genetics and epigenetics of obesity. Maturitas. 2011;69:41–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Townsend MS, Peerson J, Love B, Achterberg C, Murphy SP. Food insecurity is positively related to overweight in women. J Nutr. 2001;131(6):1738–1745. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Power ML, Schulkin J. Sex differences in fat storage, fat metabolism and the health risks from obesity: possible evolutionary origins. Br J Nutr. 2008;99(5):931–940. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507853347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mcrea JC, Mittendorfer B, Eagon JC, Patterson BW, Klein S. Lipid kinetics in extremely obese subjects before and after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity Research. 2005;13(1):200. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Rushing PA, D’Alessio D, Tso P. A controlled high-fat diet induces an obese syndrome in rats. J Nutr. 2003;133(4):1081–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merten MJ. Weight status continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: Examining disease and health risk conditions. Obesity. 2010;18:1423–1428. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katzmarzyk PT, Perusse L, Malina RM, Bouchard C. Seven-year stability of indicators of obesity and adipose tissue distribution in the Canadian population. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1123–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Popkin BM. Longitudinal physical activity and sedentary behavior trends – Adolescence to adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Wattigney WA, Berenson GS. Adolescent overweight is associated with adult overweight and related multiple cardiovascular risk factors: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Metabolism. 1996;45:235–240. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]