Abstract

This letter describes the continued chemical optimization of the VU0453595 series of M1 positive allosteric modulators (PAMs). By surveying alternative 5,6- and 6,6-heterobicylic cores for the 6,7-dihydro-5H-pyrrolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-one core of VU453595, we found new cores that engendered not only comparable or improved M1 PAM potency, but significantly improved CNS distribution (Kps 0.3 to 3.1). Moreover, this campaign provided fundamentally distinct M1 PAM chemotypes, greatly expanding the available structural diversity for this valuable CNS target, devoid of hydrogen-bond donors.

Keywords: M1, Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, Positive allosteric modulator (PAM), CNS penetration, Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)

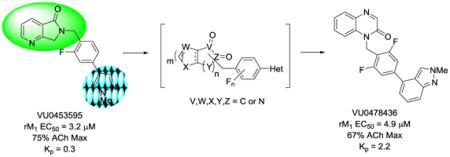

Graphical Abstract

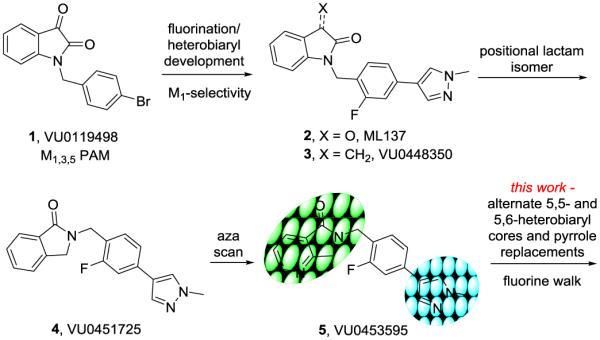

Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1 (M1) have garnered a great deal of attention as a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of the cognitive and negative symptom domains of schizophrenia, especially targeting NMDA receptor hypofunction.1-8 Moreover, M1 PAMs are also of interest in general cognition enhancement and Alzheimer’s disease.1-4,9-12 Since we reported on the discovery of the first M1 PAM, BQCA,13,14 numerous M1 PAMs have been reported in the primary and patent literature (most by scaffold hopping VU and Merck series) with many conserved moieties that consistently engender low CNS penetration (Kps < 0.3).15-25 Our latest entry into M1 PAMs was the result of three distinct high-thoughput screening campaigns,26 which resulted in novel indole-, azaindole- and isatin-based M1 PAM scaffolds.25,27-29 Of these, the isatin VU0119498 (1) was a unique PAM in that it potentiated all of the Gq-coupled mAChRs (M1, M3 and M5) with equivalent potency and efficacy.27 Subsequent optimization efforts identfied ‘molecular switches’ that gave rise to a series of highly selective M5 PAMs, 30-32 as well as ML137 (2), a highly selective M1 PAM by virtue of the fluorophenyl pyrazole moiety.28 Carbonyl deletion provided lactam 3, and surveying regioisomeric lactams afforded VU0451725 (4), with improved DMPK properties over 2 and 3.33 Finally, an aza-scan identified the the 6,7-dihydro-5H-pyrrolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-one core of VU0453595 (5), which proved a useful in vitro and in vivo tool, demonstrating efficacy in rodent models of pharmacologically-induced NMDA hypofunction.33 In this Letter, we detail an optimization campaign surveying alternative 5,6- and 6,6-heterobicyclic cores, alternate moieties for the pyrazole, and walking additional fluorines around the central phenyl ring to ultimately provide multiple novel M1 PAM scaffolds with comparable or improved rat M1 PAM potencies and improved CNS distribution (Kps 0.4 to 3.1).

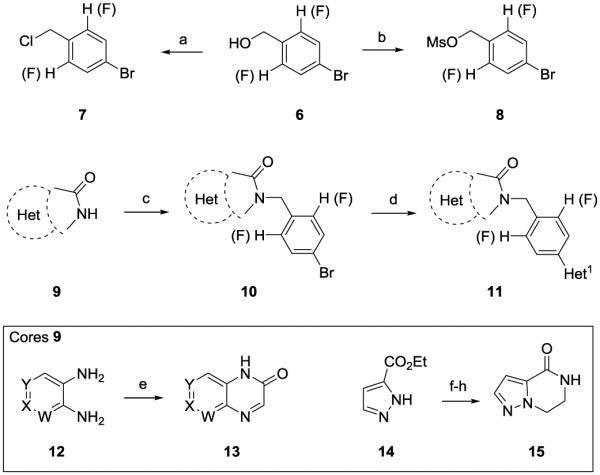

The chemistry to access new analogs, if not commercially available, was straightforward (Scheme 1).34 The fluorinated heterobiaryl tail moities were readily prepared in two steps as either a benzyl chloride 7 or a benzyl mesylate 8 from commercial benzyl alcohols 6. Various 5,6- and 6,6-heterobiaryl systems were then alkylated with either 7 or 8 to provide analogs 10. A subsequent Suzuki coupling installed the heterobiaryl motif, delivering analogs 11. Quinolinone and naphthyridinone analogs 11 of 9, were made in a single step from 12, and based on our previous work, cores such as 15 were also accessed in a simple three step procedure.34

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Ghosez’s reagent or SOCl2, DCM, rt, 65-78%; (b) MsCl, Et N, DCM, 0 °C, 75-88%; (c) 7 or 8, Cs2CO3, MeCN, 70 °C, 52-80%; (d) Het-B(OH) , Pd(dppf)Cl , Cs2CO3, THF:H20 (10:1), μw 140 °C, 22-69%; (e) ethyl glyoxalate, 51-68%; (f) Br(CH2)2NHBoc, Cs2CO2, DMF, rt, 16h, 98%; (g) HCl, 1,4-dioxane, rt, 1.5 h, 90%; (h) Na2CO3, 1,4-dioxane/H20, rt 3 hr, 90%.

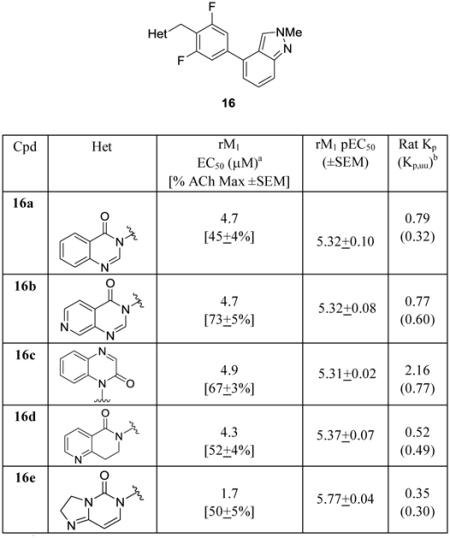

SAR was steep for the diverse analogs 11, with many compounds devoid of M1 PAM activity on both human or rat M1, or displaying species bias towards rat M1 PAM activity. In general, the 2,6-difluoro analogs were active whereas mono-fluoro and des-fluoro phenyl congeners were inactive as M1 PAMs. Representative SAR is shown in Table 1 for a subset of analogs 16, possessing an N-Me-indazole attached at the 4-position to the 2,6-difluorophenyl ring. While only rat M1 data is shown, analogs 16 were uniformly 2- to 3-fold less potent on human M1 (with many > 10 μM). Here, various 6,6-hetrobicyclic ring systems were comparably active (rM1 EC50s 4.3-4.9 μM) across quinazolin-4(3H)-ones (16a), pyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(3H)-ones (16b), quinoxalin-2(1H)-ones (16c) and naphthyridin-5(6H)-ones (16d). These analogs possessed favorable in vitro DMPK profiles (rat and human fus of 0.01 to 0.04) and moderate predicted hepatic clearance (CLheps of 40-44 mL/min/kg). However, they were superior to the lead 5 in terms of brain distribution (Kp), wherein 16a-d displayed Kps (rat brain:plasma ratios) of 0.35 to 2.16, and when corrected for fraction unbound in plasma and brain homogenate binding, the Kpuus ranged from 0.3 to 0.77 – a major advance in the context of M1 PAMs. Notably, 16c (VU0478436) afforded a >6-fold increase in CNS penetration over 5. The 5,6-congener 16e (VU0486691),based on a dihydroimidazol[1,2-c]pyrimidin-5(3H)-one core, showed enhanced M1 PAM potency (rM1 EC50 = 1.7 μM, 50% ACh Max), improved in vitro DMPK profile (rat and human fus of 0.08 and 0.04, respectively and moderate rat predicted hepatic clearance (CLhep = 40 mL/min/kg)). Moreover, 16e demonstrated a rat Kp of 0.35 and a Kpuu of 0.3. This finding led us to explore additional 5,6-heterobicyclic cores.

Table 1.

Structures and activities of analogs 16.

|

aCalcium mobilization assays with rM1-CHO cells performed in the presence of an EC20 fixed concentration of acetylcholine; values represent means from three (n=3) independent experiments performed in triplicate.

bTotal and calculated unbound braimplasma partition coefficients determinec at 0.25 hr post-administration of an IV cassette dose (0.20-0.25 mg/kg) to male, SD rat (n=1), in conjunction with in vitro rat plasma protein and brain homogenate binding assay data.

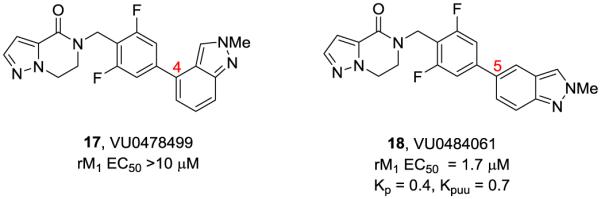

SAR proved steep as additional 5,6-hetrobicyclic cores were prepared and evaluated, with the vast majority devoid of M1 PAM activity. During this effort, it was also shown that regioisomeric N-Me indazoles had a profound effect on M1 PAM activity (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the 4-positional isomer 17 was devoid of M1 PAM activity, while in contrast, the 5-positional isomer 18 was a potent M1 PAM (EC50 = 1.7 μM, 50% ACh Max, pEC50 = 5.76+0.02) with very attractive in vitro DMPK properties (rat and human fus of 0.06 and 0.05, respectively, low rat hepatic clearance (CLhep = 29 mL/min/kg) and a large free fraction in rat brain homogenate binding, fu = 0.098). Moreover, 18 (VU0484061) possessed a rat brain:plasma ratio (Kp) of 0.40 and a Kpuu of 0.70. Once again, mL/min/kg). However, they were superior to the lead 5 in terms and in comparison to the known M1 PAMs with low Kps and Kpuus, both 16c and 18 truly stand out. It is important to point out that the majority of M1 PAMs possess two or more hydrogen bond donors (typically a trans-2-hydroxy cylohexyl amide moiety) that likely engenders the poor CNS penentration due to P-gp efflux or low permeability.13-25

Figure 2.

The impact of positional isomers of the N-Me indazole in the context of dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrazin-4-(5H)-ones 17 and 18.

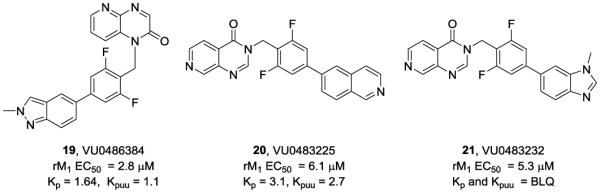

Prior to leaving this unique sub-series of M1 PAMs, one last library of analogs was prepared with more diverse tail pieces within the 16b and 16c 6,6-heterobicyclic cores. Again, SAR was steep, and few active M1 PAM resulted. However, this last campaign afforded three M1 PAMs 19-21 with diverse profiles (Fig. 3). Here, the pyrido[2,3-b]pyrazin-2(1H)-one 19 (VU0486384) was a potent and efficacious rat M1 PAM (EC50 = 2.8 μM, 80±1% ACh Max, pEC50 = 5.56±0.12), with a favorable fraction unbound in plasma (rat and human fus of 0.04), high predicted hepatic clearance (CLhep = 60 mL/min/kg), yet excellent CNS pentration (Kp = 1.64 and Kpuu = 1.1). The nature of the heterobiaryl moiety played a key role in analogous pyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-(3H)-one congeners 20 and 21. The isoquinoline analog 20 was a weak rat M1 PAM (EC50 = 6.1 μM, 42±3% ACh Max, pEC50 = 5.21±0.11) with equivalent plasma fraction unbound (fus of 0.03) for rat and human, and the best Kp to date for an M1 PAM of 3.1 (and a Kpuu of 2.7). In sharp contrast, the more basic N-Me benzimidazole congener 21 was of comparable potency (EC50 = 5.3 μM, 65±4% ACh Max, pEC50 = 5.28±0.14), good plasma fraction unbound (rat and human fus of 0.04 and 0.06, respectively), but no detectable CNS penetration (brain levels below the level of quantitation, BLQ). These data show that subtle pKa modulation can dramtically impact Kp.

Figure 3.

Additional M1 PAMs 19-21 based on 6,6-heterobicyclic cores with a diverse range of pharmacological and DMPK properties.

Finally, the concept of divergent signal bias, mediated by stabilization of unique conformers of the GPCR by the allosteric ligand, has emerged, and in many instances is critical for avoiding adverse effect liabilites.1-4,35-38 Thus, our lab surveys the propensity of new M1 PAM ligands to display signal bias.38-41 For VU0453595 (5), DiscoverRX assessed activities of the M1 PAM against human M1 in a calcium flux assay, as well on β-arrestin recruitment and internalization.39 PAM 5 was shown to be a modest human M1 PAM (EC50 = 1.9 μM, 79% ACh Max) with no effect on receptor internalization (EC50 >10 μM) and modest effect on β-arrestin recruitment (EC50 = 2.6 μM, 57% Max). New M1 PAM 16b was evaluated similarly, and was found to be a modest human M1 PAM (EC50 = 5.3 μM, 65% ACh Max) with no effect on receptor internalization (EC50 >10 μM), yet a submicromolar effect on β-arrestin recruitment (EC50 = 980 nM, 33% Max). At this point, the in vivo ramification of these profiles across signal transduction pathways are unclear, but we are tracking and noting differences between M1 PAMs and plan to investigate more thoroughly once a collection of M1 PAM ligands with diverse profiles (and comparable PK) are accumulated.

In summary, we report on the further optimization of the in vivo tool M1 PAM, VU0453595 (5). A diverse array of 5,6- and 6,6-heterobicyclic cores were developed as novel M1 PAMs with unprecedented levels of CNS penetration (Kps 0.3 to 3.1 and Kpuus of 0.3 to 2.7) and lacking the prototypical hydrogen-bond donor motifs. While these M1 PAMs are too weak to advance as clinical candidates, the improved disposition of these new chemoptypes represent fundamentally new starting points for further chemical optimization. Additional refinements are in progress and will be reported in due course.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the development of the VU0119498 series of M1 PAMs, culminating in VU0453595 (5), a moderately potent PAM (rM1 EC50 = 3.2 μM, 75% ACh Max and 3x less potent on hM1) with modest CNS penetration (Kp = 0.3). In this work, we survey alternative 5,6- and 6,6-heterobicyclic cores and pyrrole replacements in an attempt to increase CNS penetration.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for funding via the National Institute of Mental Health (2RO1MH082867, 5R01MH073676, 1U19MH106839 and 1U01MH087965). We also thank William K. Warren, Jr. and the William K. Warren Foundation who funded the William K. Warren, Jr. Chair in Medicine (to C.W.L.). P.MG. would like to acknowledge the VISP program for its support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.(a) Langmead CJ, Watson J, Reavill C. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;117:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Digby GJ, Shirey JK, Conn PJ. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6:1345–1354. doi: 10.1039/c002938f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Levey AI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:13541–13546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Felder CC, Porter AC, Skillman TL, Zhang L, Bymaster FP, Nathanson NM, Hamilton SE, Gomeza J, Wess J, McKinzie DL. Life Sci. 2001;68:2605–2613. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conn PJ, Jones C, Lindsley CW. Trends in Pharm. Sci. 2009;30:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conn PJ, Christopolous A, Lindsley CW. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conn PJ, Tamminga C, Schoepp DD, Lindsley C. 2008;8:99–105. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridges TM, LeBois EP, Hopkins CR, Wood MR, Jones JK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Drug News & Perspect. 2010;23:229–240. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.4.1416977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melancon BJ, Hopkins CR, Wood MR, Emmitte KA, Niswender CM, Christopoulos A, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:1445–1464. doi: 10.1021/jm201139r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menniti FS, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ, Pandit J, Zagouras P, Volkmann RA. Curr. Topics in Med. Chem. 2013;13:26–54. doi: 10.2174/1568026611313010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodick NC, Offen WW, Levey AI, Cutler NR, Gauthier SG, Satlin A, Shannon HE, Tollefson GD, Rasmussen K, Bymaster FP, Hurley DJ, Potter WZ, Paul SM. Arch. Neurol. 1997;54:465–473. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160091022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caccamo A, Oddo S, Billings LM, Green KN, Martinez-Coria H, Fisher A, LaFerla FM. Neuron. 2006;49:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caccamo A, Fisher A, LaFerla FM. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:112–117. doi: 10.2174/156720509787602915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CK, Brady AE, Davis AA, Xiang Z, Bubser M, Tantawy MN, Kane AS, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Bradley SR, Peterson TE, Ansari MS, Baldwin RM, Kessler RM, Deutch AY, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10422–10433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma L, Seager M, Wittman M, Bickel N, Burno M, Jones K, Graufelds VK, Xu G, Pearson M, McCampbell A, Gaspar R, Shughrue P, Danzinger A, Regan C, Garson S, Doran S, Kreatsoulas C, Veng L, Lindsley CW, Shipe W, Kuduk S, Jacobson M, Sur C, Kinney G, Seabrook GR, Ray WJ. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA. 2009;106:15950–15955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900903106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirey JK, Brady AE, Jones PJ, Davis AA, Bridges TM, Jadhav SB, Menon U, Christain EP, Doherty JJ, Quirk MC, Snyder DH, Levey AI, Watson ML, Nicolle MM, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14271–14286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3930-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang FV, Shipe WD, Bunda JL, Nolt MB, Wisnoski DD, Zhao Z, Barrow JC, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittman M, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Hartman GD, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuduk SD, Beshore DC. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014;14:1738. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140826120224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuduk SD, Beshore DC. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2012;22:1385. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.731395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto H, Sugimoto T. 2013. WO 13129622 20130906.

- 19.Yang ZQ, Shu Y, Ma L, Wittmann M, Ray WJ, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT, Kuduk SD. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:604. doi: 10.1021/ml500055h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuduk SD, Di Marco CN, Cofre V, Pitts DR, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittman M, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:657–661. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuduk SD, Di Marco CN, Saffold JR, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittman M, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT, Beshore DC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:1417–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han C, Chatterjee A, Noetzel MJ, Panarese JD, Niswender CM, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Stauffer SR. Bioorg., Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mistry SN, Lim H, Jorg M, Capuano B, Christopoulos A, Lane RJ, Scammels PJ. ACS Chem. Neurosci. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00018. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuduk SD, Chang RK, Di Marco CN, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittman M, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT, Beshore DC. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:263–267. doi: 10.1021/ml100095k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarr JC, Turlington ML, Reid PR, Utely TJ, Sheffler DJ, Cho HP, Klar R, Pancani T, Klein MT, Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Xiang Z, Daniels SJ, Niswender CM, Conn PJ, Wood MR, Lindsley CW. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012;3:884–895. doi: 10.1021/cn300068s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlo JE, Niswender CM, Luo Q, Brady AE, Shirey JK, Rodriguez AL, Bridges TM, Williams R, Days E, Nalywajko NT, Austin C, Williams M, Xiang Y, Orton D, Brown HA, Kim K, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD, Conn PJ. Mol. Pharm. 2009;75(3):577–588. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Cho HP, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1972–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid PR, Bridges TM, Sheffler DA, Cho HP, Lewis LM, Days E, Daniels JS, Jones CK, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2697–2701. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poslunsey MS, Melancon BJ, Gentry PR, Tarr JC, Mattmann ME, Bridges TM, Utley TJ, Sheffler DJ, Daniels JS, Niswender CM, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Cho HP, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Hopkins CR, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:5617–5622. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridges TM, Marlo JE, Niswender CM, Jones JK, Jadhav SB, Gentry PR, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:3445–3448. doi: 10.1021/jm900286j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghoshal A, Rook J, Dickerson J, Roop G, Morrison R, Jalan-Sakrikar N, Lamsal A, Noetzel M, Poslunsey M, Stauffer SR, Xiang Z, Daniels JS, Niswender CM, Jones CK, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:598–610. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin-Martin ML, Bartolome-Nebreda JM, Conde-Ceide S, Alonso SA, Lopez S, Martinez-Viturro CM, Tong HM, Lavreysen H, Macdonald GJ, Steckler T, Mackie C, Daniels SJ, Niswender CM, Jones CK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Stauffer SR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rook JM, Xiang Z, Lv X, Ghosal A, Dickerson J, Bridges TM, Johnson KA, Bubser M, Gregory KJ, Vinson PN, Byun N, Stauffer SR, Daniels JS, Niswender CM, Lavreysen H, Mackie C, Conde-Ceide S, Alcazar J, Bartolome JM, Macdondald GJ, Steckler T, Jones CK, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Neuron. 2015;86:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noetzel MJ, Gregory KJ, Vinson JT, Manka SR, Stauffer SR, Daniels SJ, Lindsley CW, Niswender CM, Xiang Z, Conn PJ. Mol. Pharm. 2013;83:835–847. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.082891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rook JM, Noetzel MJ, Pouliot WA, Bridges TM, Vinson PN, Cho HP, Zhou Y, Gogliotti RD, Manka JT, Gregory KJ, Stauffer SR, Dudek FE, Xiang Z, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Jones JK, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;73:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis AA, Heilman CJ, Brady AE, Miller NR, Fuerstenau-Sharpo M, Hanson BJ, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ, Lah JJ, Levey AI. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010;1:542–551. doi: 10.1021/cn100011e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. For full information on the assays, see: https://www.discoverx.com/targets/gpcr-target-biology.