SUMMARY

Setting

Even in persons with complete treatment of their first tuberculosis (TB) episode, patients with a TB history are at higher risk for having TB.

Objective

Describe factors from the initial TB episode associated with recurrent TB among patients who completed treatment and remained free of TB for at least 12 months.

Design

US TB cases, stratified by birth origin, during 1993–2006 were examined. Cox proportional hazards regression was employed to assess the association of factors during the initial episode with recurrence at least 12 months after treatment completion.

Results

Among 632 US-born patients, TB recurrence was associated with age 25–44 (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.77, 99% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–3.09, attributable fraction [AF] 1%–34%), substance use (aHR 1.57, 99%CI 1.23–2.02, AF 8%–22%), and treatment supervised by health departments (aHR 1.42, 99%CI 1.03–1.97, AF 2%–28%). Among 211 foreign-born patients, recurrence was associated with HIV infection (aHR 2.24, 99%CI 1.27–3.98, AF 2%–9%) and smear-positive TB (aHR 1.56, 99%CI 1.06–2.30, AF 3%–33%).

Conclusion

Factors associated with recurrence differed by birth origin and might be useful for anticipating greater risk for recurrent TB among certain patients with a TB history.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, reinfection, reactivation, United States

INTRODUCTION

Compared to patients with no previous history of tuberculosis (TB), patients with a history of TB are at higher risk for having TB1-3; additionally, patients with recurrent TB have poorer outcomes, including lower treatment completion and higher mortality.4,5 In addition to incomplete treatment of the first TB episode, factors associated with recurrence have included substance use, sputum smear-positive disease, cavitary pulmonary disease, and HIV infection.6-10

Elucidating factors associated with recurrence might help TB control programs and clinical providers recognize those patients with a history of TB who have a greater risk for recurrent TB so that they can explore ways of minimizing that risk. In a low-incidence setting like the United States, most recurrence has been attributed to reactivation, or incomplete cure of the first TB episode, rather than a new TB exposure resulting in reinfection.10-11

Internationally, patients who complete treatment for TB are classified as “cured” if their bacteriologically confirmed TB converts to being smear- or culture-negative; otherwise, they are classified as having “treatment completed”.12 When these two groups of patients are diagnosed with TB again later, they are considered to have “TB relapse,” regardless of how much time has elapsed.12 In contrast, the US National TB Surveillance System, which does not distinguish between “cure” and “treatment completion”, defines “recurrence” as verified TB disease in patients with a previous diagnosis who were discharged or lost to supervision for at least 12 months since the last clinical encounter for TB treatment; any TB diagnosis that occurs sooner is considered a continuation of the same TB case for national surveillance purposes (i.e., not counted as incident TB).13 Others have termed this US definition “late recurrence”8, because it explicitly excludes the majority of TB relapses which occur during and immediately following treatment.9 Applying this definition, the annual proportion of TB cases that are recurrences has persisted at a stable 4.2%–5.7% since the 1980s, despite the decline in annual TB incidence from 11 cases to 3 per 100,000 in the United States.4,13-14

Because we were interested in the group of former TB patients least expected to experience recurrence, we focused our analysis on those US patients who had uncomplicated TB that was eligible for treatment completion within 12 months, who completed treatment of the initial TB episode, and whose TB did not relapse within a year of treatment completion. We used national TB surveillance data to match individuals’ initial and recurrent TB episodes and then determine factors associated with later recurrence.

STUDY POPULATION AND METHODS

Source population and inclusion criteria

We retrospectively examined a 13-year cohort in the National TB Surveillance System of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.14 The source population for this analysis included all verified incident TB cases14 reported by health departments in the 50 states and the District of Columbia as being diagnosed and starting treatment for TB during 1993–2005 and then having uncomplicated TB that was eligible for treatment completion within 12 months13 and did, in fact, complete treatment both within 12 months and by the end of 2005.

Recurrent case ascertainment and validation process

The US National Tuberculosis Surveillance System does not include patient names, so we were unable to replicate the methodology for a similar but smaller California cohort of 148 recurrences.8 Instead, multiple TB episodes in the same patient were detected by a novel algorithm: multiple case reports from the same state with the same sex, birthdate, race, ethnicity, birth origin (US-born or foreign-born), and country of birth; further, the first TB episode year (1993–2005) had to match the previous TB episode year as reported during the recurrent TB episode (1994–2006). Confidentially, public health officials in the jurisdictions then confirmed which pairs of records represented two episodes of TB in the same patient.

Presumed single-episode comparison group

All remaining reported cases during 1993–2005 with no history of TB, a known birth origin, and that otherwise met the same inclusion criteria, were classified as the presumed single-episode comparison group, in that they were presumed not to have TB again during 1994–2006 and were assigned a censoring date for the survival analysis of December 31, 2006.

Analysis

The outcome of interest was having recurrent TB, and 27 reported demographic, clinical, and treatment-related factors at the time of the initial TB episode were considered as potential risk factors. Because birth origin strongly influences the epidemiology of TB in the United States,13 we stratified our analysis by US and foreign birth. Missing data in each category were included in the denominator for calculating percentages but not shown in the descriptive data results unless the proportion in any one stratum was >2%.

Owing to the large dataset size and large number of variables considered, we chose a statistical significance cutoff level of P < 0.01. Differences in initial TB episode characteristics were contrasted using Pearson’s chi-square tests. Cox proportional hazards regression with the outcome of recurrent TB was used to simultaneously consider multiple characteristics of the initial TB episode and determine the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and corresponding 99% confidence interval (CI) for each risk factor. The fraction of TB recurrence attributable to each risk factor, as measured at the time of the initial TB episode, was estimated by multiplying ([aHR − 1]/aHR) by the prevalence of that risk factor among persons who later experienced recurrence. Statistical data analysis was conducted with SAS version 9.3 (Statistical Analysis Software Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data were collected as part of routine TB surveillance; therefore, this retrospective analysis using existing data was not considered research and did not require approval by an institutional review board. The identities of persons were held confidential in accordance with Section 308(d) of the US Public Health Service Act.

RESULTS

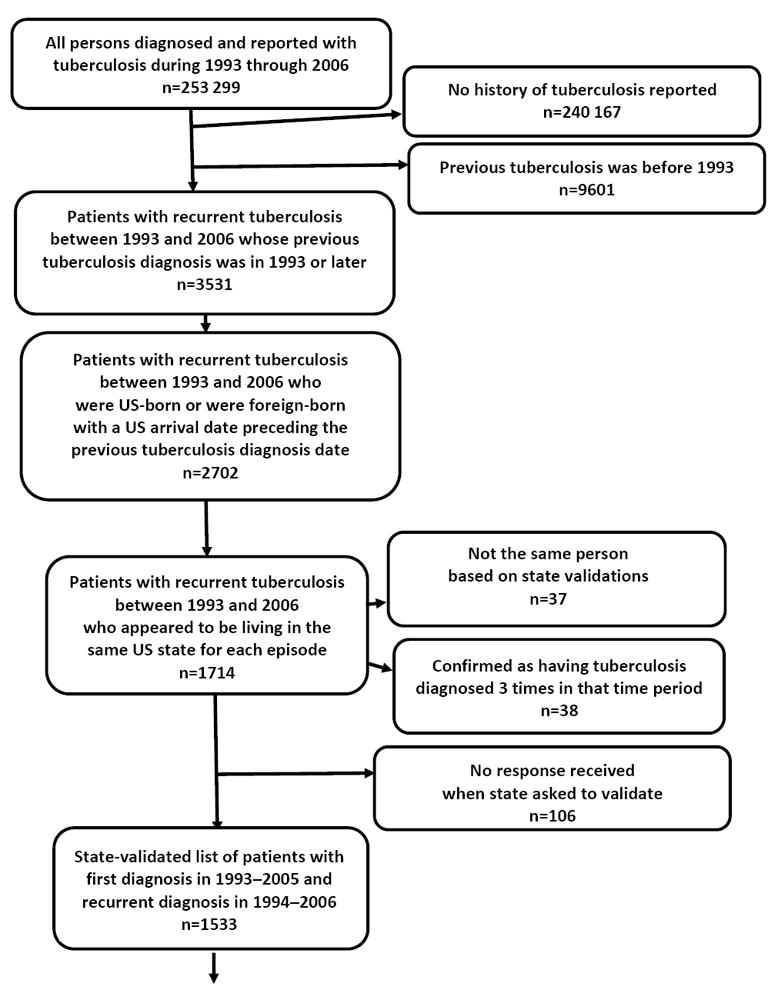

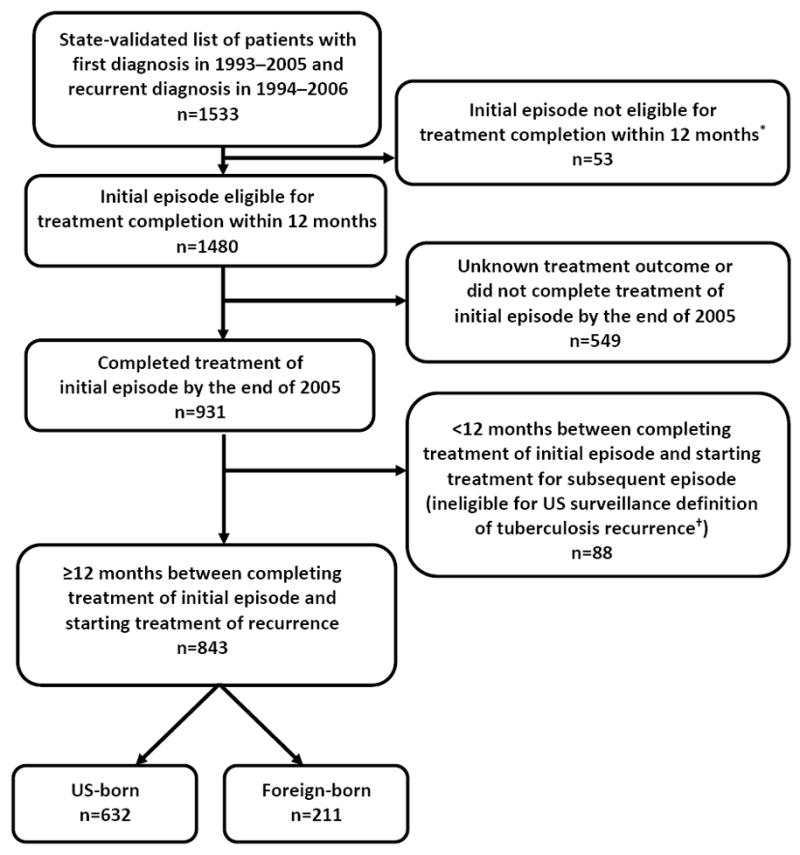

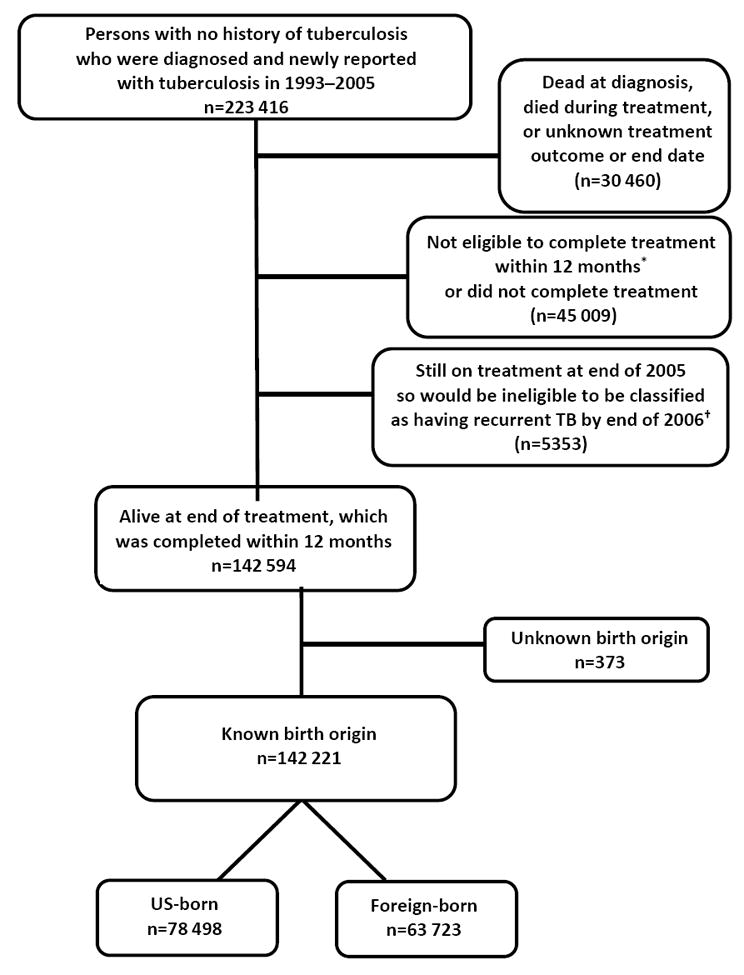

Across the United States, 2702 persons who experienced recurrent TB during 1994–2006 had a previous TB diagnosis in 1993 or later, and appeared to reside in the United States for both episodes. Of these, 1714 appeared to reside in the same US state for both episodes; states confirmed 1533 of those. These 1533 patients were further refined to the subset of 843 whose first TB episode was uncomplicated and eligible for treatment completion within 12 months, who completed treatment, and whose TB did not relapse within a year (Figure 1); their median follow-up time was 4 years (i.e., 50% of recurrent cases had occurred between 1 and 4 years later). The remaining 223 522 cases were examined for eligibility as the presumed single-episode comparison group, yielding 142 221 persons for this analysis (Figure 2); their median follow-up time was 8 years.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing inclusion criteria for persons with recurrent tuberculosis at least 12 months after treatment completion of previous tuberculosis episode, United States, 1993–2006

* Eligibility for completion of tuberculosis treatment within 12 months is defined as follows: patients have to be alive at diagnosis; initiate treatment; not die during treatment; and not have an initial isolate that is rifampin-resistant, have meningeal disease, or be a pediatric patient (aged <15) with miliary disease or positive M. tuberculosis blood culture.

† The US surveillance definition of tuberculosis recurrence is verified disease in a person with a previous diagnosis of tuberculosis who was discharged or lost to supervision for at least 12 months since the last clinical encounter for tuberculosis treatment.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram showing inclusion criteria for comparison group presumed to have single tuberculosis episode only, United States, 1993–2006

* Eligibility for completion of tuberculosis treatment within 12 months is defined as follows: patients have to be alive at diagnosis; initiate treatment; not die during treatment; and not have an initial isolate that is rifampin-resistant, have meningeal disease, or be a pediatric patient (aged <15) with miliary disease or positive M. tuberculosis blood culture.

† The US surveillance definition of tuberculosis recurrence is verified disease in a person with a previous diagnosis of tuberculosis who was discharged or lost to supervision for at least 12 months since the last clinical encounter for tuberculosis treatment.

Among the 843 persons with recurrent TB, the median time between TB episodes was 3.3 and 2.7 years for US-born and foreign-born persons, respectively. For foreign-born persons, mean duration of stay in the US was 9 years (interquartile range [IQR] 1–13 years) for those with a single TB episode and 11 years (IQR 2–16 years) before the initial TB episode for those with recurrent TB later.

At initial TB episode, US-born patients with recurrent TB were more frequently aged 25–64 years, male, or non-Hispanic black, to have used substances (i.e., excess alcohol or non-injection or injection drugs) or experienced homelessness during the previous 12 months, to be HIV-infected, or to have pulmonary, smear- and culture-positive, cavitary disease (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Foreign-born patients later diagnosed with recurrent TB were more likely to be aged 25–64 and to have HIV or sputum smear-positive TB than were foreign-born patients in the single-episode comparison group (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

CHARACTERISTICS OF INITIAL TUBERCULOSIS EPISODE AMONG PATIENTS DIAGNOSED WITH RECURRENT TUBERCULOSIS AT LEAST 12 MONTHS AFTER TREATMENT COMPLETION, CONTRASTED TO COMPARISON GROUP PRESUMED TO HAVE SINGLE EPISODE ONLY, STRATIFIED BY PATIENT BIRTH ORIGIN – UNITED STATES, 1993–2006*

| US-born patients | Foreign-born patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Characteristic of initial TB episode† | Later recurrent TB No. (%) |

Single episode only No. (%) |

P value‡ | Later recurrent TB No. (%) |

Single episode only No. (%) |

P value‡ | |

| n=632 | n=78 498 | n=211 | n=63 723 | ||||

| Age | 0–14 | 7 (1.1) | 8770 (11.2) | <0.001 | 2 (1.0) | 3042 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| 15–24 | 24 (3.8) | 4752 (6.1) | 20 (9.5) | 9981 (15.7) | |||

| 25–44 | 314 (49.7) | 23 729 (30.2) | 108 (51.2) | 26 851 (42.1) | |||

| 45–64 | 201 (31.8) | 23 577 (30.0) | 61 (28.9) | 14 846 (23.3) | |||

| ≥65 | 86 (13.6) | 17 670 (22.5) | 20 (9.5) | 9003 (14.1) | |||

| Sex | Female | 164 (25.9) | 28 393 (36.2) | <0.001 | 71 (33.7) | 26 959 (42.3) | 0.04 |

| Male | 468 (74.1) | 50 101 (63.8) | 140 (66.4) | 36 760 (57.7) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | Non-Hisp. white | 207 (32.8) | 28 369 (36.1) | <0.001 | 12 (5.7) | 4124 (6.5) | 0.25 |

| Non-Hisp. black | 359 (56.8) | 35 917 (45.8) | 26 (12.3) | 7807 (12.3) | |||

| Hispanic | 41 (6.5) | 10 495 (13.4) | 97 (46.0) | 23 680 (37.2) | |||

| Asian | 2 (0.3) | 1035 (1.3) | 76 (36.0) | 27 509 (43.2) | |||

| American Indian | 23 (3.6) | 1812 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.1) | |||

| Native Hawaiian | 0 (0) | 328 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 112 (0.2) | |||

| Multiple | 0 (0) | 40 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 49 (0.1) | |||

| Substance use§ | No | 261 (41.3) | 50 613 (64.5) | <0.001 | 162 (76.8) | 54 078 (84.9) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 281 (44.5) | 18 561 (23.7) | 25 (11.9) | 4313 (6.8) | |||

| Unknown | 90 (14.2) | 9324 (11.9) | 24 (11.4) | 5332 (8.4) | |||

| Homeless in past 12 months | No | 497 (78.6) | 68 425 (87.2) | <0.001 | 200 (94.8) | 59 760 (93.8) | 0.75 |

| Yes | 97 (15.4) | 6146 (7.8) | 3 (1.4) | 1370 (2.1) | |||

| Unknown | 38 (6.0) | 3927 (5.0) | 8 (3.8) | 2593 (4.1) | |||

| Correctional facility resident at diagnosis | No | 598 (94.6) | 74 395 (94.8) | 0.12 | 205 (97.2) | 62 562 (98.2) | 0.48 |

| Yes | 24 (3.8) | 3430 (4.4) | 5 (2.4) | 886 (1.4) | |||

| Employment | Employed | 225 (35.6) | 25 121 (32.0) | 0.02 | 107 (50.7) | 30 758 (48.3) | 0.15 |

| Unemployed | 323 (51.0) | 44 482 (56.7) | 79 (37.4) | 27 302 (42.8) | |||

| Unknown | 84 (13.2) | 8895 (11.3) | 25 (11.9) | 5663 (8.9) | |||

| HIV | Not positive¶ | 540 (85.4) | 71 484 (91.1) | <0.001 | 187 (88.6) | 60 972 (95.7) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 92 (14.6) | 7014 (8.9) | 24 (11.4) | 2751 (4.3) | |||

| Anatomic site of disease | Extrapulmonary | 41 (6.5) | 11 672 (14.9) | <0.001 | 37 (17.5) | 13 632 (21.4) | 0.52 |

| Pulmonary | 554 (87.7) | 62 214 (79.3) | 163 (77.3) | 46 338 (72.7) | |||

| Both | 37 (5.9) | 4592 (5.8) | 11 (5.2) | 3745 (5.9) | |||

| Acid-fast bacilli smear result (any site) | Negative | 195 (30.9) | 34 580 (44.1) | <0.001 | 85 (40.3) | 33 452 (52.5) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 414 (65.5) | 36 828 (46.9) | 122 (57.8) | 27 239 (42.7) | |||

| Unknown | 23 (3.6) | 7090 (9.0) | 4 (1.9) | 3032 (4.8) | |||

| Culture result (any site) | Negative | 40 (6.3) | 13 566 (17.3) | <0.001 | 28 (13.3) | 12 441 (19.5) | 0.005 |

| Positive | 581 (91.9) | 58 749 (74.8) | 180 (85.3) | 48 503 (76.1) | |||

| Unknown | 11 (1.7) | 6183 (7.9) | 3 (1.4) | 2779 (4.4) | |||

| Cavity visible on chest radiograph** | No | 326 (57.0) | 43 632 (68.7) | <0.001 | 116 (69.1) | 35 125 (72.7) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 223 (39.0) | 17 700 (27.9) | 49 (29.2) | 12 279 (25.4) | |||

| Unknown | 23 (4.0) | 2144 (3.4) | |||||

| Documented sputum culture conversion†† | Yes | 453 (88.1) | 35 933 (81.9) | 0.001 | 116 (80.0) | 29 748 (84.6) | 0.29 |

| No | 55 (10.7) | 6896 (15.7) | 26 (17.9) | 4755 (13.5) | |||

| Unknown | 6 (1.2) | 1040 (2.2) | 3 (2.1) | 655 (1.9) | |||

| Initial drug regimen | Standard 4-drug | 445 (70.4) | 50 372 (64.2) | 0.005 | 177 (83.9) | 52 007 (81.6) | 0.14 |

| INH and RIF only | 29 (4.6) | 4073 (5.2) | 1 (0.5) | 1690 (2.7) | |||

| Other | 158 (25.0) | 24 053 (30.6) | 33 (15.6) | 10 026 (15.7) | |||

| TB drugs administration method | Directly observed | 360 (57.0) | 37 518 (47.8) | <0.001 | 73 (34.6) | 26 299 (41.3) | 0.19 |

| Self-administered | 122 (19.3) | 22 188 (28.3) | 77 (36.5) | 19 969 (31.3) | |||

| Both | 145 (22.9) | 18 132 (23.1) | 60 (28.4) | 16 902 (26.5) | |||

| TB provider type | Private/other | 89 (14.1) | 16 932 (21.6) | <0.001 | 46 (21.8) | 13 609 (21.4) | 0.03 |

| Health dept. | 357 (56.5) | 38 328 (48.8) | 115 (54.5) | 37 265 (58.5) | |||

| Both | 183 (29.0) | 22 523 (28.7) | 46 (21.8) | 12 532 (19.7) | |||

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; INH = isoniazid; RIF = rifampin

Note that study design limits analysis to patients who were living in the same US state for both TB episodes.

Unknowns for each category are included in the denominator for calculating percentages but are not shown unless the proportion was >2%.

Pearson chi-square test.

Includes non-injection drug use, injection drug use, and excess alcohol use 12 months prior.

Includes those that tested HIV negative, refused, not offered, HIV test done but result unknown, result indeterminate, and result unknown.

Among those with pulmonary disease or both pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease and chest radiograph consistent with TB (among US-born, n=572 for patients with later recurrent TB, n=63,476 for presumed single-episode cases; among foreign-born, n=168 for patients with later recurrent TB, n=48,313 for presumed single-episode cases).

Among patients with a positive sputum culture (among US-born, n=514 for patients with later recurrent TB, n=43,869 for presumed single-episode cases; among foreign-born, n=145 for patients with later recurrent TB; n=35,158 for presumed single-episode cases).

Table 2 shows the results of the Cox proportional hazards model for factors associated with recurrent TB disease, stratified by birth origin. Having the initial TB episode occur after 2002 appeared protective against recurrence for both US-born and foreign-born persons. Among the US-born, factors during the initial episode independently associated with recurrence included age 25–44 years (aHR 1.77, 99%CI 1.02–3.09), substance use (aHR 1.57, 99%CI 1.23–2.02), and treatment supervised by health departments (aHR 1.42, 99%CI 1.03–1.97). Foreign-born patients later diagnosed with recurrent TB were more likely HIV-infected (aHR 2.24, 99%CI 1.27–3.98) or to have smear-positive TB (aHR 1.56, 99%CI 1.06–2.30) during the initial episode. Corresponding attributable fractions among the US-born were 22% (1%–34%) for age 25 44 years, 16% (8%–22%) for substance use, and 17% (2%–28%) for health department treatment; and among the foreign-born were 6% (2%–9%) for HIV infection and 21% (3%–33%) for smear-positive TB at the time of the initial TB episode.

TABLE 2.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH RECURRENT TUBERCULOSIS AT LEAST 12 MONTHS AFTER TREATMENT COMPLETION, STRATIFIED BY PATIENT BIRTH ORIGIN – UNITED STATES, 1993–2006

| US-born patients | Foreign-born patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Characteristic of initial TB episode | Adjusted Hazard Ratio | 99% Confidence Interval | P value* | Adjusted Hazard Ratio | 99% Confidence Interval | P value* | |

| Age | 0–14 | 0.30 | 0.09–1.00 | <.0001 | 0.53 | 0.07–3.81 | 0.005 |

| 15–24 | Ref | -- | Ref | -- | |||

| 25–44 | 1.77 | 1.02–3.09 | 1.81 | 0.96–3.41 | |||

| 45–64 | 1.24 | 0.70–2.18 | 1.95 | 1.00–3.79 | |||

| ≥65 | 0.99 | 0.54–1.82 | 1.10 | 0.49–2.49 | |||

| Sex | Female | Ref | -- | 0.13 | |||

| Male | 1.21 | 0.95–1.54 | |||||

| Race/ethnicity† | Non-Hispanic White | Ref | -- | 0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.14 | 0.90–1.44 | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.67 | 0.43–1.05 | |||||

| Asian | 0.65 | 0.10–4.08 | |||||

| American Indian | 1.43 | 0.81–2.54 | |||||

| Substance use‡ | No | Ref | -- | <.0001 | Ref | -- | 0.20 |

| Yes | 1.57 | 1.23–2.02 | 1.50 | 0.86–2.63 | |||

| Unknown | 1.28 | 0.90–1.83 | 1.02 | 0.56–1.83 | |||

| Homeless in past 12 months | No | Ref | -- | 0.42 | |||

| Yes | 1.17 | 0.86–1.59 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.01 | 0.62–1.63 | |||||

| HIV | Not positive§ | Ref | -- | 0.17 | Ref | -- | 0.001 |

| Positive | 1.18 | 0.87–1.62 | 2.24 | 1.27–3.98 | |||

| Anatomic site of disease | Extrapulmonary | Ref | -- | 0.87 | |||

| Pulmonary | 1.17 | 0.70–1.94 | |||||

| Both | 1.14 | 0.60–2.16 | |||||

| Acid-fast bacilli smear result (any site) | Negative | Ref | -- | 0.04 | Ref | -- | 0.01 |

| Positive | 1.26 | 0.99–1.61 | 1.56 | 1.06–2.30 | |||

| Unknown | 1.32 | 0.69–2.54 | 0.81 | 0.19–3.50 | |||

| Culture result (any site) | Negative | Ref | -- | 0.07 | Ref | -- | 0.41 |

| Positive | 1.57 | 0.92–2.69 | 1.23 | 0.70–2.15 | |||

| Unknown | 1.04 | 0.37–2.92 | 0.68 | 0.12–3.85 | |||

| Cavity visible on chest radiograph | No | Ref | -- | 0.05 | |||

| Yes | 1.25 | 0.99–1.58 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.19 | 0.74–1.90 | |||||

| Documented sputum culture conversion | Yes | Ref | -- | 0.01 | |||

| No | 0.80 | 0.55–1.16 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.65 | 0.43–0.97 | |||||

| Initial drug regimen | Standard 4-drug | Ref | -- | 0.11 | |||

| INH and RIF only | 1.56 | 0.92–2.64 | |||||

| Other | 1.00 | 0.78–1.29 | |||||

| TB drugs administration method | Directly observed | Ref | -- | 0.10 | |||

| Self-administered | 0.77 | 0.57–1.05 | |||||

| Both | 0.85 | 0.65–1.10 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.97 | 0.30–3.13 | |||||

| TB provider type | Private/other | Ref | -- | 0.02 | |||

| Health department | 1.42 | 1.03–1.97 | |||||

| Both | 1.24 | 0.88–1.75 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.82 | 0.18–3.77 | |||||

| Year of initial TB episode¶ | 1993–1996 | Ref | -- | <.0001 | Ref | -- | <.0001 |

| 1997–2002 | 0.88 | 0.70–1.11 | 0.62 | 0.42–0.91 | |||

| 2003–2006 | 0.25 | 0.14–0.43 | 0.19 | 0.09–0.40 | |||

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; INH = isoniazid; RIF = rifampin

Native Hawaiian, multi-racial/ethnicity, and unknown categories not shown as no comparison between patients with later recurrent TB and presumed single-episode cases could be made.

Includes non-injection drug use, injection drug use, and excess alcohol use in past 12 months.

Includes those that tested HIV negative, refused, not offered, HIV test done but result unknown, result indeterminate, and result unknown.

This term was added to adjust for possible secular trends that might not have been accounted for in the model, such as the evolving epidemiology of HIV during the study period.

DISCUSSION

This analysis of US national surveillance data found that persons with uncomplicated TB who completed treatment within 12 months, and whose TB did not relapse within a year, had certain identifiable risk factors at the time of their initial TB episode associated with a higher risk of TB recurrence later, and these factors differed on the basis of birth origin. In general, social risk factors were associated with recurrent TB among US-born patients, whereas clinical characteristics appeared to play a greater role among foreign-born patients. Among US-born patients, recurrence was associated with ages 25–44 years, substance use, and treatment managed by a health department during the initial TB episode. Among foreign-born patients, initial episode factors associated with recurrence were ages 45–64 years, HIV infection, and smear-positive disease.

Although US public health departments continue to play an integral role in TB treatment and adherence, including provision of directly observed therapy, our study found that recurrent TB among US-born was associated with treatment by health departments. This unexpected association might be explained by confounding by indication (i.e., some unmeasured social risk factor that led to both initial treatment in the public sector as well as later recurrence). For example, the finding of substance use as a risk factor for recurrent TB underscores the importance in countries with low TB incidence of engaging with society’s most socially marginalized and vulnerable populations to address broader determinants of health.15-18

In 2003, American guidelines were revised to more forcefully advocate for the standard 4-drug regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol.9,19 Even after adjustment for secular trend, being treated with only isoniazid and rifampin had a borderline association (99%CI 0.92–2.64) with TB recurrence among the US-born. Although this suboptimal regimen was rarely used (<5% of the study population), this finding further validates the importance of current treatment recommendations.9

Interestingly, we found HIV infection to be independently associated with TB recurrence among foreign-born but not among US-born patients. This finding might be due to US-born patients’ increased access to healthcare, including better linkages to HIV treatment and care, compared to foreign-born patients. Additionally, if a substantial proportion of US-born, single-episode patients had HIV prior to antiretroviral therapy introduction, then other opportunistic infections may have caused death before TB could recur, blunting the contribution of HIV to the risk of TB recurrence among US-born patients in this analysis. Likewise, our survival analysis assigned everyone in the comparison group the same censoring date as their end point, but persons with other immunocompromising conditions or advanced age were more likely to have an earlier, but unknown, censoring date.

Several other limitations also deserve mention. We were limited to the information routinely collected in the US National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, which at the time did not include potentially important variables such as diabetes, tobacco use, and nutrition status. Our study population represents longtime US residents well, but our findings might be less generalizable to more recent immigrants or geographically mobile individuals. Patients in the single-episode comparison group who experienced TB recurrence in another state/country or after 2006 were misclassified. Nevertheless, of the 2702 total persons who appeared to be living in the United States for both of their TB episodes during 1993–2006, over half (1533) were confirmed by states as having been accurately identified by our algorithm. In addition, our internal analysis did not reveal any geographic trends or differences (data not shown). Finally, because our study period occurred before widespread use of TB genotyping, only 24 patients, or 2.8% of our study population, had TB genotyping results available for both TB episodes, precluding us from being able to examine our assumption that the majority of these recurrences had the etiology of reactivation (i.e., incomplete cure of the first TB episode). As genotyping surveillance coverage subsequently increased to 88.2%,20 future analyses will be able to discriminate between the proportions of recurrent TB attributable to endogenous reactivation and exogenous reinfection in the United States.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the largest and first nationally representative study in the United States to examine previous TB episodes in persons who later experienced TB recurrence. Clinicians are already aware that a history of TB, even among those considered to have completed adequate treatment, is an independent risk factor for TB. This analysis suggests particular factors, which might differ by birth origin, are identifiable during the initial episode. While rapid diagnosis and treatment remain the mainstays of TB control, being able to recognize those patients at highest risk of recurrence might lead to better integration with substance abuse programs and optimal management of HIV infection at the time of and following the initial TB episode.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following health department colleagues who assisted with data validation: S Austin, N Baruch, J Bettridge, A Bravo, C Clark, T Condren, S Cook, T Crisp, P Davidson, B Elms, S Etkind, E Funk, S Ghosh, T Goins, M Gosciminski, P Griffin, K Guillen, J Harclerode, K Hedberg, K Herrin, E Holt, S Hughes, P Infield, D Ingman, S Jones, Y Luster-Harvey, A Lynch, S Marsden, D Merz, T Miazad, M Miner, J Montero, J Moore, L Mukasa, T Oemig, S Paulson, L Phillips, S Poonja, T Privett, S Quilter, S Rabley, J Rodman, R Sales, L Sandman, K Schaller, W Sutherland, D Thai, and others. We also thank A Appiagyei, L Armstrong, J Becerra, M Iademarco, J Jereb, P LoBue, R Miramontes, T Navin, J Oeltmann, and R Pratt for their contributions.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MBH, LK, and PKM conceived and designed the study. MBH acquired and validated the data with the respective public health jurisdictions. LK and MBH performed the analysis with assistance from PKM, CMH, RSYW, and JSK. All authors were involved with data interpretation and manuscript preparation, and they approved the final submitted version.

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Millet JP, Orcau A, de Olalla PG, Casals M, Cayla JA. Tuberculosis recurrence and its associated risk factors among successfully treated patients. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:799–804. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verver S, Warren RM, Beyers N, et al. Rate of reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment is higher than rate of new tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1430–1435. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1200OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panjabi R, Comstock GW, Golub JE. Recurrent tuberculosis and its risk factors: adequately treated patients are still at high risk. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:828–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim L, Moonan PK, Yelk Woodruff RS, Kammerer JS, Haddad MB. Epidemiology of recurrent tuberculosis in the United States 1993–2010. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:357–360. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray J, Sonnenberg P, Shearer SC, Godfrey-Faussett P. Human immunodeficiency virus and the outcome of treatment for new and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis in African patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;149:733–740. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golub JE, Durovni B, King BS, et al. Recurrent tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS. 2008;22:2527–2533. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328311ac4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacho J, Perez Meixeira A, Cano I, et al. Recurrent tuberculosis from 1992 to 2004 in a metropolitan area. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:333–337. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pascopella L, DeRiemer K, Watt JP, Flood JM. When tuberculosis comes back: who develops recurrent tuberculosis in California? PloS One. 2011;6:e26541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:603–662. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.4.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettit AC, Kaltenbach LA, Maruri F, et al. Chronic lung disease and HIV infection are risk factors for recurrent tuberculosis in a low-incidence setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:906–911. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jasmer RM, Bozeman L, Schwartzman K, et al. Recurrent tuberculosis in the United States and Canada: relapse or reinfection? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1360–1366. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1081OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis — 2013 Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2013. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopanoff DE, Snider DE, Jr, Johnson M. Recurrent tuberculosis: why do patients develop disease again? Am J Public Health. 1988;78:30–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. The End TB Strategy: a global rally. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:943. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasanathan K, Sivasankara Kurup A, Jaramillo E, Lönnroth K. The social determinants of health: key to global tuberculosis control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:S30–S36. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeltmann JE, Kammerer JS, Pevzner ES, Moonan PK. Tuberculosis and substance abuse in the United States 1997–2006. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:189–197. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deiss RG, Rodwell TC, Garfein RS. Tuberculosis and illicit drug use: review and update. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:72–82. doi: 10.1086/594126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1359–1374. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis Genotyping in the United States, 2004–2010. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]