Abstract

DCLK1 is a gastrointestinal (GI) tuft cell kinase that has been investigated as a biomarker of cancer stem-like cells in colon and pancreatic cancers. However, its utility as a biomarker may be limited in principle by signal instability and dilution in heterogeneous tumors, where the proliferation of diverse tumor cell lineages obscures the direct measurement of DCLK1 activity. To address this issue, we explored the definition of a microRNA signature as a surrogate biomarker for DCLK1 in cancer stem-like cells. Utilizing RNA/miRNA sequencing datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas, we identified a surrogate 15-miRNA expression signature for DCLK1 activity across several GI cancers, including colon, pancreatic and stomach cancers. Notably, Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that this signature could predict the survival of patients with these cancers. Moreover, we identified patient subgroups that predicted the clinical utility of this DCLK1 surrogate biomarker. Our findings greatly strengthen the clinical significance for DCLK1 expression across GI cancers. Further, they provide an initial guidepost toward the development of improved prognostic biomarkers or companion biomarkers for DCLK1-targeted therapies to eradicate cancer stem-like cells in these malignancies.

Introduction

Doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1) is a tuft cell and tumor stem cell marker that is important in colon and pancreatic carcinogenesis [1–5]. Studies in murine models show that DCLK1 both specifically identifies tumor stem and stem-like cells and can serve as a potential therapeutic anti-tumor target with no apparent toxicity to normal cells or cellular homeostasis [1, 2, 5]. Moreover, DCLK1 has been tightly linked to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is important in the metastatic processes of many tumors including those of the gastrointestinal tract [6, 7]. However, although DCLK1 marks cells that initiate tumors and is expressed in the primary tumor, circulating tumor cells [8] and in metastases [9], expression levels of DCLK1 may be unstable. DCLK1 expression levels have a tendency to decrease with advancing disease status [3] possibly due to increased proliferation of tumor stem cell-derived progeny that make up the bulk of the tumor. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to determine whether direct measurements of DCLK1 levels in patients could be clinically useful as a biomarker [3].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a uniquely stable set of ubiquitously expressed small non-coding RNAs that regulate complex processes during both homeostasis and in disease. In cancer, miRNAs modulate stemness, EMT, expression of tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes, and many other essential pathways that phenotypically affect cancer cells such as drug-resistance, tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis [10–14]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Project has collected and disseminated large multi-site datasets that allow for assessment of the prognostic and diagnostic value of protein, RNA, and other markers, including miRNAs, in the setting of malignancy. In the present study, we utilized these datasets to identify a stable, surrogate miRNA-signature for DCLK1 activity in tumors, and to study the prognostic significance of this signature in patients with cancers of the colon, pancreas, and stomach.

Materials and Methods

TCGA Pan-Gastrointestinal Cancer Data

The miRNA and RNA-seq datasets from February 2015 data runs for colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), rectal adenocarcinoma (READ), and stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) were downloaded from the UCSC Cancer Genome Browser [15, 16].

Determination of DCLK1-associated miRNAs

Illumina HiSeq V2 RNAseq and miRNA seq data were loaded into R v3.2 and Pearson correlations were calculated for each miRNA against DCLK1 mRNA expression in the 5 cancers derived from organs that are thought to contain tuft cells (colon, esophagus, pancreas, rectum, and stomach) [1, 5, 17]. The resulting correlation p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for each cancer correcting for multiple comparisons and reducing false discoveries. A Bonferroni-adjusted p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Consensus miRNAs that were significantly correlated to DCLK1 expression in all cancer types were selected to create a DCLK1 miRNA-derived signature (Supplemental Figure 1).

KEGG Pathway Analysis

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) curated pathway analysis (pathways union) was performed using DIANA miRPath v.2.0 [18] using Tarbase as a reference. All miRNAs with Tarbase references were included in the analysis and a targeted pathway heatmap was generated with a P-value threshold of 0.05.

Statistical Analysis

Basic statistical analyses were performed in R v3.2 and Graphpad Prism 6.0. Kaplan-Meier Survival analyses were performed in Graphpad Prism 6.0. Cox regression analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. Circos plots for miRNAs across cancers were generated using the RCircos R package [19]. Correlation plots were generated using the corrplot R package. Heatmaps were generated using Genesis. Receiver operating characteristic predictions were generated using the PrognosticROC R package [20].

Clinical Patient Characteristics

Only publicly available, de-identified data were accessed from TCGA for the analyses reported here. Basic characteristics of the patients used in the survival analyses (colon, pancreas, and stomach) are provided in Supplemental Table 1. The average age was between 65 and 67 years for all three cancers. Gender was split approximately evenly between males and females for colon and pancreatic cancer, but the number of males in the stomach cancer group was significantly greater (286 males vs 165 females). Cox regression analysis demonstrated that tumor burden, disease stage, and nodal invasion were important survival factors in all three cancers while distant metastases were factors in colon and stomach cancer.

Cell Lines

SW480 colon cancer and AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cell lines were obtained directly from ATCC where they were tested and authenticated via morphology, karyotyping, and PCR to rule out interspecies and intraspecies contamination. Cells were cultured under standard conditions at 37°C in RPMI medium with 10% FBS.

Overexpression and siRNA-mediated knockdown of DCLK1

DCLK1 isoform 1 or vector control was expressed in AsPC-1 cells utilizing lentivirus as previously described [21]. Overexpression was confirmed by Western blot. Knockdown of DCLK1 was achieved via transfecting SW480 cells with 50 nM of DCLK1-specific siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-456178) or scrambled siRNA confirmed not to target any human genes for 72 h using Lipofectamine 3000 (Sigma). Efficient knockdown was confirmed by Western blot.

Western blot

Western blotting was performed as previously described [7] using specific primary antibodies against DCLK1 (Abcam 88484) and Beta-Actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-1616), and IRdye 700 and 800 secondary antibodies (Licor). Results were visualized on a Licor Odyssey Infrared Imager and analyzed in ImageStudio (Licor).

miRNA-specific qPCR

Total miRNAs were isolated from treated cells using a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturers instructions. Mature miRNAs were amplified by polyadenylation followed by reverse-transcription using an All-in-One miRNA First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Genecopoeia). Following reverse transcription, qPCR was performed using experimentally validated, specific commercial miRNA primers (Genecopoeia). Results were calculated via the delta-delta CT method using U6 as a housekeeping miRNA.

Results

DCLK1 Expression is Correlated to EMT Across Gastrointestinal Cancers

Analysis of all 6 cancer types demonstrated a strong correlation between DCLK1 mRNA expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition as determined by the EMT spectrum score previously described (Figure 1A) [22]. DCLK1 was most strongly correlated to EMT in colon and rectal cancers followed by cancers of the pancreas, stomach, esophagus, and liver. Although DCLK1 was significantly correlated to EMT in liver cancer, the level of correlation was approximately 3-fold less when compared to colon and almost 2-fold less than the next least correlated cancer (Figure 1A). It appears that in hepatocellular cancer, EMT transcription factors and mesenchymal markers are correlated with DCLK1, but the loss of epithelial marker expression is not. This finding suggests that EMT in GI-tract cancers may be a process that is directly related to the presence of tuft cells that are known to be present in the esophagus, stomach, intestine, and pancreas but not the liver. Further studies will be necessary to determine if this relationship involves a hijacking of the tuft cell’s sensory and/or secretory function [17, 23, 24] during mutation and tumorigenesis.

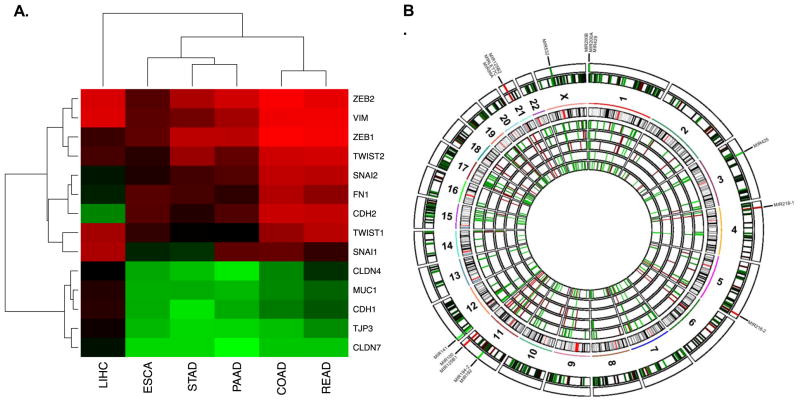

Figure 1. A 15-microRNA signature correlates to tumor stem cell marker DCLK1 across five gastrointestinal tumor types.

A. DCLK1 is strongly correlated to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in all TCGA gastrointestinal cancer datasets, especially those originating in organs with tuft cells present in normal tissue. B. Circos schematic of expression of DCLK1-activity correlated miRNAs with chromosomal location. From inner to outer concentric circles: COAD, ESCA, PAAD, READ, and STAD miRNA expression correlations; representation of HG18 chromosome cytobands; combined miRNA expression correlations for all 5 cancers; consensus significant miRNA expression correlations with labels.

Determination of a microRNA Signature for DCLK1 Tumor Activity

Pearson correlations were performed to determine DCLK1’s association with miRNA expression across the 5 tuft-cell containing organ tumors. This analysis revealed a consensus of 15 significantly correlated miRNAs: miR-99a, Let-7c, miR-125b-1, miR-125b-2, miR-532, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-429, miR-425, miR-218-1, miR-218-2, miR-192, miR-194-2, miR-100, and miR-141 (Figure 1B). Comparison of this signature between low DCLK1-expressing (0–25th percentile) and high DCLK1-expressing (75–100th percentile) tumors confirmed the veracity of these findings (Figure 2). Moreover, high miRNA-signature tumors demonstrated greatly increased levels of EMT as well as DCLK1 expression when compared to low signature tumors (Figure 3A–B).

Figure 2. Dysregulated expression of the 15-microRNA signature is present in tumors expressing high levels of DCLK1.

Heatmaps demonstrating dysregulated expression of the 15-miRNA signature between DCLK1-low and DCLK1-high patients from the TCGA COAD, ESCA, PAAD, READ, and STAD datasets.

Figure 3. DCLK1 directly regulates expression of the 15-microRNA signature.

Boxplots demonstrating increased expression of DCLK1 (A) and increased EMT status (B) between miRNA-signature low (miR Low) and miRNA-signature high (miR high) tumors in all 5 tuft cell-containing GI cancers from the TCGA COAD, ESCA, PAAD, READ, and STAD datasets (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). C–D. SW480 cells express high levels of DCLK1. Downregulation of DCLK1 in this cell line via DCLK1-targeted siRNA results in upregulation of miR-141, miR-200a-b, miR-425, and miR-532 while overexpression of DCLK1 in the AsPC-1 cell line which expresses nearly undetectable levels of DCLK1 results in downregulation of these same markers (E–F)(*p<0.05).

The derived signature supports our previous finding that DCLK1 is both associated with and regulates miR-200 EMT suppressors [4, 25]. Additionally, we observed changes in expression of 4 key miRNA-clusters including the miR-99a/125b-2/Let-7c stemness-associated cluster (upregulated); the miR-200a/200b/429 EMT-suppressor cluster (downregulated); the miR-192/194-2/200c tumor suppressor and p53-inducer cluster (downregulated); and the miR-100/125b-2 EMT-inducer cluster (upregulated). Interestingly, the expression of miRNAs that demonstrate shared sequence motifs but distant chromosomal locations were correlated to DCLK1 expression (e.g. miR-125b-1/2 and miR-281-1/2) suggesting targeted specificity for DCLK1 or vice-versa. These findings, in consideration of our previously reported studies, suggest that DCLK1 is capable of inducing a stemness and EMT-supporting miRNA signature that may have significant implications in GI tumorigenesis.

To determine whether any of the miRNAs in the signature are directly regulated by DCLK1, we isolated mature miRNAs from SW480 cells, which express high endogenous levels of DCLK1, following transfection with scrambled or DCLK1-targeted siRNA – and from AsPC-1 cells, which express very low levels of DCLK1, stably expressing control vector or DCLK1. For both of these sets of cells we isolated proteins to confirm the desired changes in DCLK1 expression. miRNA-specific reverse transcription and real-time PCR revealed that at least 5 of the miRNAs in the signature are directly regulated by DCLK1 in a binary fashion. Specifically, miR-141, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-425, and miR-532 are all upregulated by DCLK1 knockdown (Figure 3C–D) and downregulated by DCLK1 overexpression (Figure 3E–F) in agreement with their correlation to DCLK1 in the TCGA datasets. These findings strongly suggest that the relationship between the derived miRNA signature and DCLK1 is not merely correlative, but that DCLK1 directly regulates at least one-third of the miRNAs that make up the signature.

To further assess the potential functional relevance of this DCLK1-specific miRNA signature, we subjected the 15-miRNA signature to KEGG pathway analysis using mirPath (DIANA Tools) with Tarbase as a reference for gene targets. Out of the 15 miRNAs, 11 had gene targets listed in Tarbase. Generation of KEGG pathways based on these targets revealed interesting enrichments for cancer-related pathways in which DCLK1 is known to have functional significance including colorectal, pancreatic, and renal cell cancers [3, 7, 21]. Additionally, important processes that affect tumor initiation and progression such as tight junction-regulating targets and TGF-beta signaling among others were also enriched (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. The 15-microRNA signature demonstrates enrichment of key oncogenic pathways and predicts survival in colon, pancreatic, and stomach cancer.

A. Heatmap of significant pathways induced by the miRNA-signature as determined by KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using DIANA miRPath including colorectal, pancreatic, and renal cell cancer pathways – all cancers in which DCLK1 activity has been demonstrated to have significant functional activity. B. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrating that a DCLK1-activity based 15-miRNA signature predicts overall (p<0.05) and recurrence-free survival (p<0.005) in colon cancer patients, C. predicts overall (p<0.05) survival in pancreatic cancer patients, and D. predicts overall (p<0.05) and recurrence-free survival (p<0.01) in stomach cancer patients (green: low miRNA-signature expression, orange: mid miRNA-signature expression, red: high miRNA-signature expression).

A DCLK1-based 15-miRNA Signature Predicts Survival in Colon and Pancreatic Cancer

Following determination of the miRNA signature and its potential functional significance we sought to determine if the signature could predict survival in any of the 5 studied cancers. An overall signature metric was calculated by summing values for upregulated miRNAs and subtracting values for downregulated miRNAs. Patients were grouped by level of signature expression into low (0–25th percentile), mid (25–75th percentile), and high expression (75–100th percentile). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that the DCLK1-derived miRNA signature could be used to strongly predict both overall and recurrence-free survival in colon cancer. All of the colon cancer patients in the high signature expression group experienced a recurrence of disease by approximately 75 months and no patient survived beyond month 100. In contrast, less than 20% of patients with a low expression signature experienced a recurrence by approximately 150 months and overall survival remained at 70% for this time period (Figure 4B).

In pancreatic cancer patients, the signature was able to significantly predict overall survival, but not recurrence-free survival. In patients with mid to high level signature expression <15% of patients remained alive after approximately 73 months. However, approximately half of the patients with low signature expression survived to 90 months (Figure 4C). Although analysis of recurrence-free survival did not reach statistical significance, there was a nearly 25–30% increase of recurrence observed among patients with high signature expression as compared to those with mid and low signature expression (Figure 4C). Further studies utilizing a larger patient sample are required to determine if this signature can serve as a predictor of both overall and recurrence free survival.

The DCLK1-derived miRNA signature did not predict overall or recurrence-free survival in patients with esophageal or rectal carcinoma, probably due to small sample size (data not shown). However, it was predictive of overall and recurrence-free survival in gastric adenocarcinoma (Figure 4D). These data taken together suggest that the 15-miRNA signature presented here as a surrogate for DCLK1 activity in gastrointestinal cancers may serve as a potential prognostic marker, especially those derived from organs with DCLK1-positive tuft cells.

Sub-group Analysis of the 15-miRNA Survival Signature

In order to better understand the prognostic significance of the miRNA signature in patients with colon, pancreatic, or gastric cancer, we performed Cox regression analysis on clinical subgroups stratified by low and high-risk miRNA-signature and compared the resulting hazard ratios. In colon cancer, early stage patients without signs of nodal or distant metastases who demonstrated high signature expression had a 2 – 4 fold higher hazard ratio when assessing overall survival (Figure 5A). In those with pancreatic cancer, the high-risk signature appeared to be strongly predictive of overall survival in patients under the age of 65, but of limited use in older patients (Figure 5A). Finally in gastric cancer patients, high signature expression was consistent for most subgroups assessed, but may be most useful for patients under the age of 65 (Figure 5A). It also may have some prognostic value for patients undergoing radiation therapy (Figure 5A) – which may be related to DCLK1’s tumor stem cell role, as these cells are expected to be resistant to radiation. We confirmed the significance of the miRNA-signature to overall survival in the subgroups described above by Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 5B). Moreover, we performed further subgroup analyses to assess the value of the miRNA-signature in recurrence-free survival and found that the signature was mostly consistent across subgroups and that in pancreatic cancer the signature was again most valuable in patients under the age of 65 (Supplemental Figure 2). These data suggest that the miRNA-signature may have clinical value in specific subsets of patients.

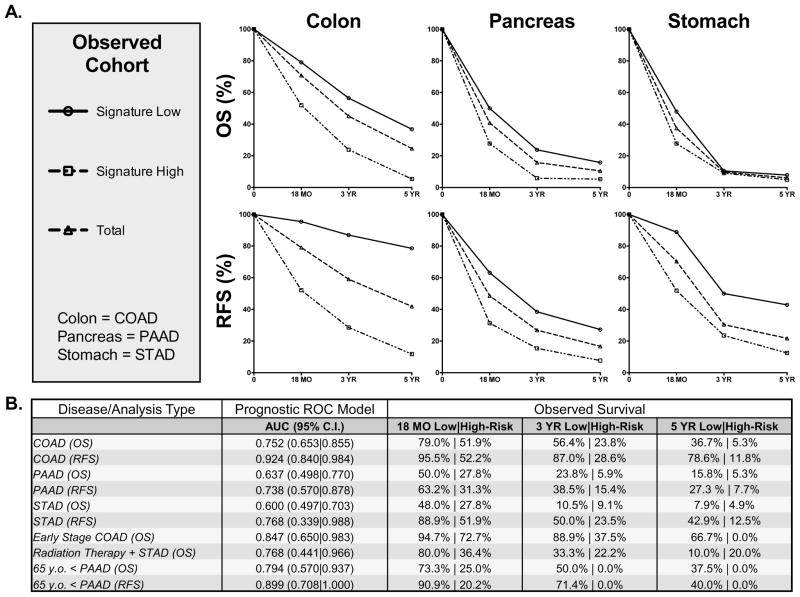

Figure 5. Subgroup analysis highlights key clinical attributes related to the prognostic significance of the 15-microRNA signature.

A. Subgroup analysis of overall survival in low risk compared to high-risk miRNA-signature tumors in TCGA COAD, PAAD, and STAD datasets demonstrating the prognostic value of the signature in certain subsets of patients. B. Kaplan-Meier analysis of select patient subsets demonstrating the prognostic significance of the signature in Stage I–II colon cancer patients (p<0.01), pancreatic cancer patients under 65 years old (OS: p<0.02; RFS: p<0.008), and stomach cancer patients receiving radiation therapy (Log-Rank: p=0.078; Gehan-Breslow: p=0.022).

Observed Survival and Receiver-Operating Characteristics of the 15-miRNA Survival Signature

To further assess the signature we divided the patients into groups with definite outcomes at 18 months, 3 years, and 5 years post-diagnosis and determined observed survival percentages. The signature performed well in colon, pancreas, and stomach cancer datasets both in terms of overall and recurrence-free survival. Patients with the low-risk signature demonstrated better actual survival while patients with the high-risk signature demonstrated poorer actual survival than total (Figure 6A). The TCGA datasets utilized here are a work in progress and it is not possible to define the specificity and sensitivity of the miRNA-signature with current data. In order to estimate their probable value, we utilized the PrognosticROC R package to estimate the probable R.O.C area under the curve (AUC) for the signature (Figure 6B). Values ranged from approximately 0.65 – 0.98 in colon cancer, 0.50 – 0.88 in pancreatic cancer, and 0.34 – 0.99 in stomach cancer. For the subgroups discussed in Figure 5, values ranged from approximately 0.44 – 1. These findings suggest that this miRNA-signature may have significant value as a prognostic tool in colon, pancreatic, and stomach cancers and demonstrate that the signature can be used in practice to predict patient risk of death and recurrence.

Figure 6. The 15-microRNA signature delineates retrospective survival of colon, pancreatic, and stomach cancer patients at 18 months, 3 years, and 5 years.

A. Comparison of observed survival by miRNA signature expression among patients with definite outcomes in the TCGA colon, pancreas, and stomach cancer datasets. B. Predicted prognostic receiver operating characteristic (R.O.C) data for colon (COAD), pancreas (PAAD), and stomach (STAD) cancer datasets as well as relevant subgroups as modeled by the prognosticROC statistical package and observed survival in patients with known outcomes at 18 months, 3 years, and 5 years post-diagnosis.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal cancers are commonly observed malignancies, and virtually all of these arise from normal tissue containing DCLK1+ tuft cells. These cells are thought to be involved in sensory functions and signaling during cellular homeostasis and in response to injury [17, 23, 24]. Moreover, strongly increased expression of DCLK1 is observed in both pre-cancerous lesions and cancers of these organs [1, 2, 5, 9, 26, 27], suggesting clonal expansion of DCLK1+ cells during tumor initiation and/or activation of downstream of oncogenic signaling. Recently, the presence of DCLK1 tumor stem and stem-like cells [27, 28] has been confirmed in models of colon and pancreatic cancer [1, 2, 5], elevating the importance of this marker. However, the development of prognostic biomarkers in GI cancers has been slow, but developing markers based on an essential target like DCLK1 may have the potential to improve treatment strategies and increase patient quality of life and survival.

DCLK1 has been measured in patient blood, on circulating tumor cells and in tumor tissues, and functionally it is highly related to cancer initiation and EMT [2–4]. However, the use of DCLK1 expression as a biomarker remains controversial because of the complicated nature of its isoforms, which despite high homology may demonstrate altered expression in various tumors [7, 29]. Also, DCLK1 expression may decrease in advanced stage tumors [3]. We speculate that this apparent decrease in DCLK1 expression may result from a dilution effect caused by the proliferation of diverse tumor lineages. However, we hypothesize that the limitations to using DCLK1 directly as a biomarker could be overcome by developing a stable molecular signature indicative of DCLK1 activity.

MicroRNAs demonstrate exceptional stability even in difficult biological samples such as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections, blood, and urine [30, 31] and have been used as prognostic biomarkers in a number of cancers [32]. Moreover, several recent reports suggest that DCLK1 regulates EMT through a miRNA-dependent mechanism, which has also been confirmed in pancreatic and colon cancer using tumor xenograft models [25, 33]. In this study, we utilized miRNA and RNA-sequencing datasets made available by The Cancer Genome Atlas Project to determine a stable surrogate 15-miRNA signature for DCLK1 activity in GI cancers. Furthermore, these miRNA signatures were subjected to KEGG pathway analysis confirming their functional relevance through their association with cancer initiation and progression related pathways.

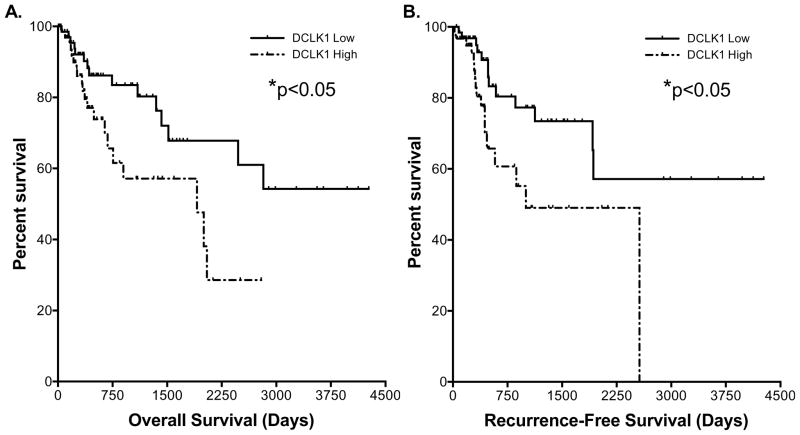

Using Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analysis, we found that the 15-miRNA signature was able to predict survival in colon, pancreas, and gastric cancers. The signature had the strongest predictive ability in colon cancer where strong data supports a DCLK1+ cell origin for the APC mutant form of this cancer [2, 5] and emerging data suggests a role in the KRAS mutant counterpart [34]. It is notable that the signature was particularly effective at predicting overall survival in patients with early stage (I–II) disease. Strikingly, when compared to early stage patients, early stage patients with high signature expression (HR: 2.751; 95% C.I.: 1.429|11.560) demonstrate poor survival consistent with advanced stage (III–IV) disease (HR: 2.851; 95% C.I.: 1.879|4.765) as confirmed by Kaplan-Meier analysis (p=0.314). This finding highlights the clinical potential of this miRNA signature, and with further validation it may be used to identify high-risk early stage patients that might require more aggressive treatment and follow-up. Additionally, in all stages of disease the high-risk signature predicted a dramatically increased recurrence hazard (>7-fold compared to the low-risk profile). These findings support the role of the DCLK1-based miRNA signature in determining a prognosis for colon cancer patients. We note that a number of groups have demonstrated that DCLK1 expression can predict survival in colon cancer [9, 35]. Although we found similar significant results using DCLK1 gene expression data from the TCGA colon cancer RNA-seq dataset (Figure 7), the DCLK1-based miRNA signature was able to stratify risk with much greater efficiency.

Figure 7. DCLK1 gene expression predicts survival in colon cancer.

A. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrating that colon cancer patients with high DCLK1 gene expression (top 25th percentile) have significantly reduced overall (p<0.05, HR: 2.214) and B. recurrence-free (p<0.05, HR: 2.433) survival compared to those with low expression (bottom 25th percentile).

As in colon cancer, the signature was able to predict overall and recurrence-free survival in gastric cancer. The signature demonstrated better predictive ability in younger (<65 years old) and female patients with a hazard ratio of approximately 3 for these groups. Because gastric cancer is characterized by high associated mortality, predictable biomarkers may greatly improve disease stratification, diagnosis, and treatment protocols. However, attempts to develop biomarkers based on alterations on the gene and protein level have so far failed to produce useful, stable assays for gastric cancer patients [35]. Previous research has shown that female gender and diffuse histopathology are often seen in younger patients with gastric cancer [36], and that these tumors are molecularly unique and more aggressive than tumors in elderly patients [37, 38]. Screening these patients with the DCLK1-based miRNA signature has the potential to allow clinicians to pursue different treatment strategies in high-risk gastric cancer patients. Another interesting finding was the ability of the signature to predict overall survival in patients receiving radiotherapy. Although the confidence interval for this assessment was wide, this finding may support a stem-like role for DCLK1 in stomach cancer, as cancer stem cells are known to resist radiotherapy.

Finally, despite a small sample size (n=163), the signature was able to predict overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Additionally, there was a trend towards predicting recurrence free survival among the stratified groups, but this did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the small sample size (n=138). Pancreatic cancer carries a very poor prognosis and the utility of biomarkers is unclear. However, there is emerging evidence to suggest that DCLK1 might serve as a new target for pancreatic cancer treatment [1, 3, 4, 21, 39, 40]. To this end, we are currently pursuing DCLK1-targeted agents and this signature may prove useful in determining patients who might benefit from anti-DCLK1 therapies.

Our findings presented here are novel in that we used the expression of the DCLK1 tumor stem cell marker as a guide to derive a unique, potentially stable miRNA signature that predicts survival in patients with colon, gastric and pancreatic cancer. To our knowledge, this may be the first time this type of literature-informed technique has been used to determine a prognostic biomarker signature and may be worth exploring further with other known, important targets. Our results indicate that the prediction efficiency of the miRNA signature is associated with tumor pathology, stage, and treatment strategy and we believe it will be important to take these clinical factors into consideration while further developing this signature and other markers. Furthermore, these results lend support to a potential pan-gastrointestinal role for the DCLK1+ tuft cell and tumor stem cell and the functional significance of DCLK1 in colon, pancreatic, and gastric cancer. Finally, our findings suggest that the DCLK1-based miRNA signature should be studied further and has the potential to define new therapies for colon, gastric and pancreatic malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: A Veterans Affairs Merit Review (1I01BX001952) and NIH R21 (1R21CA186175-01A1) supported this work.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Courtney Houchen and Edwin Bannerman-Menson are co-founders of COARE Biotechnology Inc.

References

- 1.Bailey JM, Alsina J, Rasheed ZA, McAllister FM, Fu YY, Plentz R, et al. DCLK1 Marks a Morphologically Distinct Subpopulation of Cells with Stem Cell Properties in Pre-invasive Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanishi Y, Seno H, Fukuoka A, Ueo T, Yamaga Y, Maruno T, et al. Dclk1 distinguishes between tumor and normal stem cells in the intestine. Nature genetics. 2013;45(1):98–9103. doi: 10.1038/ng.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu D, Johnson J, Chandrakesan P, Weygant N, May R, Aiello N, et al. Doublecortin-like kinase 1 is elevated serologically in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and widely expressed on circulating tumor cells. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0118933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sureban SM, May R, Qu D, Weygant N, Chandrakesan P, Ali N, et al. DCLK1 regulates pluripotency and angiogenic factors via microRNA-dependent mechanisms in pancreatic cancer. PloS one. 2013;8(9):e73940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westphalen CB, Asfaha S, Hayakawa Y, Takemoto Y, Lukin DJ, Nuber AH, et al. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(3):1283–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI73434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandrakesan P, Weygant N, May R, Qu D, Chinthalapally HR, Sureban SM, et al. DCLK1 facilitates intestinal tumor growth via enhancing pluripotency and epithelial mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2014;5(19):9269–80. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weygant N, Qu D, May R, Tierney RM, Berry WL, Zhao L, et al. DCLK1 is a broadly dysregulated target against epithelial-mesenchymal transition, focal adhesion, and stemness in clear cell renal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(4):2193–205. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantara C, O’Connell MR, Luthra G, Gajjar A, Sarkar S, Ullrich RL, et al. Methods for detecting circulating cancer stem cells (CCSCs) as a novel approach for diagnosis of colon cancer relapse/metastasis. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagliardi G, Goswami M, Passera R, Bellows CF. DCLK1 immunoreactivity in colorectal neoplasia. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2012;5:35–42. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S30281. Epub 2012/05/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang C-J, Chao C-H, Xia W, Yang J-Y, Xiong Y, Li C-W, et al. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties through modulating miRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(3):317–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garofalo M, Romano G, Di Leva G, Nuovo G, Jeon YJ, Ngankeu A, et al. EGFR and MET receptor tyrosine kinase-altered microRNA expression induces tumorigenesis and gefitinib resistance in lung cancers. Nature medicine. 2012;18(1):74–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Lu Y, Govindan R, Wang L, Liu PY, Goodgame B, Wen W, et al. MicroRNA profiling and prediction of recurrence/relapse-free survival in stage I lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(5):1046–54. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nimmo RA, Slack FJ. An elegant miRror: microRNAs in stem cells, developmental timing and cancer. Chromosoma. 2009;118(4):405–18. doi: 10.1007/s00412-009-0210-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wellner U, Schubert J, Burk UC, Schmalhofer O, Zhu F, Sonntag A, et al. The EMT-activator ZEB1 promotes tumorigenicity by repressing stemness-inhibiting microRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(12):1487–95. doi: 10.1038/ncb1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saqui-Salces M, Keeley TM, Grosse AS, Qiao XT, El-Zaatari M, Gumucio DL, et al. Gastric tuft cells express DCLK1 and are expanded in hyperplasia. Histochem Cell Biol. 2011;136(2):191–204. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0831-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlachos IS, Kostoulas N, Vergoulis T, Georgakilas G, Reczko M, Maragkakis M, et al. DIANA miRPath v.2.0: investigating the combinatorial effect of microRNAs in pathways. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W498–504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H, Meltzer P, Davis S. RCircos: an R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Combescure C, Perneger TV, Weber DC, Daures JP, Foucher Y. Prognostic ROC curves: a method for representing the overall discriminative capacity of binary markers with right-censored time-to-event endpoints. Epidemiology. 2014;25(1):103–9. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weygant N, Qu D, Berry WL, May R, Chandrakesan P, Owen DB, et al. Small molecule kinase inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 demonstrates potent activity against colorectal and pancreatic cancer through inhibition of doublecortin-like kinase 1. Molecular cancer. 2014;13(1):103. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salt MB, Bandyopadhyay S, McCormick F. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition rewires the molecular path to PI3K-dependent proliferation. Cancer discovery. 2014;4(2):186–99. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerbe F, van Es JH, Makrini L, Brulin B, Mellitzer G, Robine S, et al. Distinct ATOH1 and Neurog3 requirements define tuft cells as a new secretory cell type in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(5):767–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.May R, Qu D, Weygant N, Chandrakesan P, Ali N, Lightfoot SA, et al. Brief report: Dclk1 deletion in tuft cells results in impaired epithelial repair after radiation injury. Stem cells. 2014;32(3):822–7. doi: 10.1002/stem.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sureban SM, May R, Lightfoot SA, Hoskins AB, Lerner M, Brackett DJ, et al. DCAMKL-1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic cells through a miR-200a-dependent mechanism. Cancer research. 2011;71(6):2328–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2738. Epub 2011/02/03. 0008-5472.CAN-10-2738 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sureban SM, May R, Ramalingam S, Subramaniam D, Natarajan G, Anant S, et al. Selective blockade of DCAMKL-1 results in tumor growth arrest by a Let-7a MicroRNA-dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):649–59. 59 e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.004. Epub 2009/05/19. S0016-5085(09)00748-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May R, Riehl TE, Hunt C, Sureban SM, Anant S, Houchen CW. Identification of a novel putative gastrointestinal stem cell and adenoma stem cell marker, doublecortin and CaM kinase-like-1, following radiation injury and in adenomatous polyposis coli/multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Stem cells. 2008;26(3):630–7. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0621. Epub 2007/12/07. 2007-0621 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May R, Sureban SM, Lightfoot SA, Hoskins AB, Brackett DJ, Postier RG, et al. Identification of a novel putative pancreatic stem/progenitor cell marker DCAMKL-1 in normal mouse pancreas. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2010;299(2):G303–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00146.2010. Epub 2010/06/05. ajpgi.00146.2010 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vedeld HM, Skotheim RI, Lothe RA, Lind GE. The recently suggested intestinal cancer stem cell marker is an epigenetic biomarker for colorectal cancer. Epigenetics. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.4161/epi.27582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xi Y, Nakajima G, Gavin E, Morris CG, Kudo K, Hayashi K, et al. Systematic analysis of microRNA expression of RNA extracted from fresh frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples. RNA. 2007;13(10):1668–74. doi: 10.1261/rna.642907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mall C, Rocke DM, Durbin-Johnson B, Weiss RH. Stability of miRNA in human urine supports its biomarker potential. Biomark Med. 2013;7(4):623–31. doi: 10.2217/bmm.13.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li MH, Fu SB, Xiao HS. Genome-wide analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression signatures in cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(10):1200–11. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sureban SM, May R, Mondalek FG, Qu D, Ponnurangam S, Pantazis P, et al. Nanoparticle-based delivery of siDCAMKL-1 increases microRNA-144 and inhibits colorectal cancer tumor growth via a Notch-1 dependent mechanism. Journal of nanobiotechnology. 2011;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond DE, Mageean CJ, Rusilowicz EV, Wickenden J, Clague MJ, Prior IA. Differential reprogramming of isogenic colorectal cancer cells by distinct activating K-Ras mutations. Journal of proteome research. 2015 doi: 10.1021/pr501191a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudler P. Challenges of deciphering gastric cancer heterogeneity. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015;21(37):10510–27. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo JY, Jin EH, Jo HJ, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular features associated with patient age in gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015;21(22):6905–13. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsieh FJ, Wang YC, Hsu JT, Liu KH, Yeh CN. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of gastric cancer patients aged 40 years or younger. Journal of surgical oncology. 2012;105(3):304–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.22084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park JC, Lee YC, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee SK, Hyung WJ, et al. Clinicopathological aspects and prognostic value with respect to age: an analysis of 3,362 consecutive gastric cancer patients. Journal of surgical oncology. 2009;99(7):395–401. doi: 10.1002/jso.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sureban SM, May R, Weygant N, Qu D, Chandrakesan P, Bannerman-Menson E, et al. XMD8-92 inhibits pancreatic tumor xenograft growth via a DCLK1-dependent mechanism. Cancer letters. 2014;351(1):151–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou B, Irwanto A, Guo YM, Bei JX, Wu Q, Chen G, et al. Exome sequencing and digital PCR analyses reveal novel mutated genes related to the metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13(10):871–9. doi: 10.4161/cbt.20839. Epub 2012/07/17. 20839 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.