Abstract

Patient: Female, 34

Final Diagnosis: Refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Symptoms: Fatigue

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Plasma exchange

Specialty: Rheumatology • Hematology and Critical Care

Objective:

Rare co-existance of disease or pathology

Background:

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is one of the thrombotic microangiopathic (TMA) syndromes, caused by severely reduced activity of the vWF-cleaving protease ADAMTS13. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), on the other hand, is an autoimmune disease that affects various organs in the body, including the hematopoietic system. SLE can present with TMA, and differentiating between SLE and TTP in those cases can be very challenging, particularly in patients with no prior history of SLE. Furthermore, an association between these 2 diseases has been described in the literature, with most of the TTP cases occurring after the diagnosis of SLE. In rare cases, TTP may precede the diagnosis of SLE or occur concurrently.

Case Report:

We present a case of a previously healthy 34-year-old female who presented with dizziness and flu-like symptoms and was found to have thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and schistocytes in the peripheral smear. She was subsequently diagnosed with TTP and started on plasmapheresis and high-dose steroids, but without a sustained response. A diagnosis of refractory TTP was made, and she was transferred to our facility for further management. Initially, the patient was started on rituximab, but her condition continued to deteriorate, with worsening thrombocytopenia. Later, she also fulfilled the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria for diagnosis of SLE. Treatment of TTP in SLE patients is generally similar to that in the general population, but in refractory cases there are few reports in the literature that show the efficacy of cyclophosphamide. We started our patient on cyclophosphamide and noticed a sustained improvement in the platelet count in the following weeks.

Conclusions:

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is a life-threatening hematological emergency which must be diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. Refractory cases of TTP have been described in the literature, but without clear evidence-based guidelines for its management, and is solely based on expert opinion and previous case reports. Further studies are needed to establish guidelines for its management. We present this case to highlight the role that cyclophosphamide might carry in those cases and to be a foundation for these future studies.

MeSH Keywords: Cyclophosphamide; Lupus Erythematosus, Discoid; Purpura, Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic

Background

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is one of the thrombotic microangiopathic (TMA) syndromes, caused by severely reduced activity of the vWF-cleaving protease ADAMTS13 [1]. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), on the other hand, is an autoimmune disease that can affect various organs and systems in the body, including the hematopoietic system [2,3]. SLE can present with TMA, and differentiating between SLE and TTP can be very challenging, particularly in patients with no prior history of SLE [2]. Furthermore, an association between these 2 diseases has been described in the literature, with most of the TTP cases occurring after the diagnosis of SLE. In rare cases, TTP may precede the diagnosis of SLE or occur concurrently [4].

Case Report

A 34-year-old Jamaican female with no previous medical problems presented to an outside hospital because of syncope. Review of systems was remarkable for flu-like symptoms, nausea, and dizziness for a few days prior to presentation. She reported a skin rash over her chest and abdomen, which resolved prior to coming to the United States. Review of systems was negative for photosensitivity, joints pain, oral ulcers, and chest pain.

Her vital signs on presentation were noted for tachycardia 115 beats per minute, BP 121/74 mmHg, no distress, and scars over her chest and abdomen from the previous skin rashes. Respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological examinations were otherwise unremarkable.

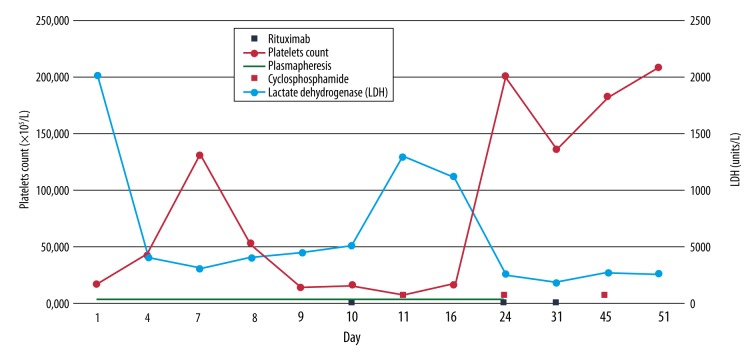

Initial laboratory tests showed anemia; hemoglobin 6.0 g/dL (12.0–16.0 g/dL), thrombocytopenia; platelets count 17,000×106/L (150–450×106/L), and white blood cells (WBC) count of 9,000×106/L (4–11×109/L). Total bilirubin was 4.7 mg/dL (0.2–1.3 mg/dL), direct bilirubin was undetectable, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated at 2,022 U/L (reference range 84–246 U/L); haptoglobin was undetectable; and peripheral smear showed numerous schistocytes (10–15 per high-power field). Prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and renal function test were within normal limits. Serology for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and direct Coombs tests were negative. No proteinuria was found. Other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory tests.

| Variable | Reference range, adults | 1st day | 7th day | 9th day | 16th day | 24th day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 84–246 Units/L | 2022 | 311 | 453 | 1117 | 262 |

| Platelets count | 150–450×106/L | 17,000 | 132,000 | 14,000 | 17,000 | 202,000 |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 12.0–16.0 g/dL | 6 | 8.4 | 7 | 7.4 | 10.6 |

| Potassium | 3.6–5.2 mmol/L | 4.1 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 4 | 3.7 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | 7–18 mg/dL | 21 | 23 | 19 | 30 | 12 |

| Creatinine | 0.6–1.3 mg/dL | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Aspartate transferase (AST) | 15–37 Units/L) | 90 | 55 | 36 | 85 | 29 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.2–1.3 mg/dL | 4.7 | 1.1 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 1.3 |

| Prothrombin Time (PT) | 9.25–12.35 seconds | 11.4 | ||||

| Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) | 25–33.9 seconds | 26.4 | ||||

| Direct bilirubin | 0.0–0.2 mg/dL | Undetectable | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Haptoglobin | 30–200 mg/dL | Undetectable | ||||

| Fibrinogen | 186–477 mg/dL | 349 | 330 | 222 | ||

| Complements total CH50 | 42–62 Units/mL | 39 | ||||

| C3 | 75–140 mg/dL | 98 | 80 | |||

| C4 | 10–34 mg/dL | 12 | 12 | |||

| SS-A(Ro) Ab | ≤0.9 AI | Undetectable | ||||

| SS-B (La) Ab | ≤0.9 AI | Undetectable | ||||

| dsDNA Ab | <30 International unit/L | Undetectable | ||||

| CRP | ≤3.0 mg/L | 1.2 | 3 | |||

| ESR | mm/hour | 14 | 3 | |||

| Ferritin | 10–290 ng/mL | 8068 | 520 | |||

| Antiphospholipid panel | Negative | |||||

| ADAMTS13 activity | >50% | <5% | ||||

| ADAMTS13 Inhibitor | ≤0.4 Inhibitor units | 3.6 | ||||

| ANA | <1:80 | (1:640) | (1:160) | |||

| Anti-Smith Ab | <1.0 AI | 3.2 | ||||

| Anti-RNP Ab | <1.0 AI | 0.4 |

Figure 1.

A Timeline of the platelet count and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and their relation with treatment options (Plasmapheresis, Rituximab, and Cyclophosphamide).

Based on those findings, diagnosis of TTP was made and therapy with plasma exchange and methylprednisone (2 mg/kg) daily was initiated. After 6 days of therapy, improvement was noted on the blood test, with platelets peaked to 132,000×106/L and LDH down to 331 U/L. Soon after, the platelets went down again, to 14×109/L. Refractory TTP was suspected and the patient was transferred to our hospital for further management.

Results of other laboratory test were: ANA 1: 640 speckled (normal <1:80), anti-Smith antibodies 3.2 AI (normal <1.0 AI), ADAMTS13 activity severely reduced <5% (normal >67%), with presence of ADAMTS13 inhibitors; 3.6 inhibitor units (IU) (normal is <0.4 IU)

We resumed plasma exchange and methylprednisone (2 mg/kg) therapy and added rituximab (375 mg/m2) on the first day and was planned for weekly administration. The patient did not respond to the rituximab treatment. Her first week in our center was complicated with 1 episode of generalized tonic clonic seizure, which was attributed to the worsening TTP. We assumed that her TTP was refractory to rituximab therapy; therefore, pulse steroid therapy (1 g daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (500 mg every 2 weeks) were added. After 1 week, her platelet count improved to 202,000×106/L, and LDH and other hemolysis parameters (e.g., AST, direct bilirubin) started to decrease. We continued cyclophosphamide for 2 more cycles (2 weeks apart), plasmapheresis daily for total of 24 days (starting on the day of admission to the other facility), then every 2 days for 3 more cycles, and started prednisone taper prior to discharge.

Discussion

Several disorders can present with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) and thrombocytopenia. These includes the primary thrombomicroangiopathy (TMA) syndromes, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura TTP (hereditary or acquired), shiga toxin-mediated hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), drug-induced TMA (DITMA), metabolism-induced TMA (rare hereditary disorders of vitamin B12 metabolism), and coagulation-induced TMA. Certain systemic disorders can also present with TMA: rheumatologic disorders; pre-eclampsia/HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome; severe HTN; systemic infection; systemic malignancy; severe vitamin B12 deficiency; and complications of hematopoietic stem cell or organ transplantation.

TMA is a pathological diagnosis made by biopsy, characterized by thrombosis in the microvasculature (i.e., arterioles and capillaries) [1], but biopsy is not needed in the appropriate clinical settings.

Lupus rarely presents with thrombotic MAHA (TMA) [2,3]. It can also be associated with neurological abnormalities, renal involvement, and fever, which are the typical triad of features characteristic of TTP. SLE and TTP occurring simultaneously in an individual patient have rarely been reported in the literature. Whether this occurrence is just a coincidence or represents a true association is largely an unanswered question as there have only been a few such cases reported to date) [4]. Of note, TTP may also occur before or subsequent to SLE, which poses an equal challenge. The underlying pathophysiology of SLE-related TMA is frequently heterogeneous because it can also be due to anti-phospholipid syndrome or vasculitis [5,6], which explains why is it imperative to differentiate TMA related to lupus from primary TTP, since any delay in the administration of plasma exchange (PEX) has significant consequences in terms of increased mortality [2].

Although our patient had no prior history of SLE, and she presented with features suggestive of TTP, her recent history of scarring rash (on chest and abdomen) was challenging in differentiating between these 2 conditions. Her negative Coombs test at presentation is very important here, as it suggested primary TTP as the most likely etiology of her thrombotic MAHA. Later, during her hospital course, she was found to have laboratory evidence of TTP, including severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (<10%), and positive ADAMTS13 inhibitor activity (TTP). We also found laboratory evidence of SLE, such as high titer of ANA, positive anti-Smith antibodies, and reduced total complement level (fulfilling the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/SLICC criteria for diagnosis of SLE).

TTP can be hereditary or acquired. Acquired TTP is characterized by a severe deficiency of vWF protease ADAMTS13 due to an inhibitor (autoantibody) directed against ADAMTS13. However, documentation of a severe deficiency of plasma ADAMTS13 activity (less than 10% of normal) is not essential for the diagnosis of TTP (see below) [7]. In contrast, hereditary TTP is characterized by severe deficiency of ADAMTS13 due to biallelic mutations in the ADAMTS13 gene.

The incidence of acquired TTP is approximately 3 cases per 10 (6) adults per year [8]. The median age for the diagnosis of acquired TTP diagnosis is 41 years. Demographic features associated with an increased risk of TTP include female sex and black race. NOTE: these are similar to the demographic features of SLE [9].

Acquired TTP usually presents as severe MAHA and thrombocytopenia, sometimes in a previously healthy individual. It can also present in patients with other autoimmune disorders, such as SLE. Whether it is due to a combination of shared demographic features and/or similar pathophysiology is unknown. Initial symptoms may include fatigue, dyspnea, petechiae, or bleeding [10]. Organ involvement in TTP often affects the central nervous system and/or gastrointestinal system. GI manifestations are common and include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or abdominal pain. Neurologic findings may include difficulty speaking or transient numbness and weakness, seizures, and coma. Subtle changes such as confusion and headache are especially common [11]. Although acute kidney injury is uncommon, renal involvement can be seen on renal biopsy. Other organs (e.g., the heart) may also be affected, and there can be a wide range of manifestations (e.g., MI, CHF, and SCD) that are often unrecognized causes of increased morbidity and mortality in patients with TTP [12,13]. Pulmonary involvement is rare. A review of 65 cases with acquired TTP from the Oklahoma TTP-HUS Registry revealed that 34% of patients had no neurologic symptoms, and that high fever and chills, chest pain, and cough were seen in less than one-third of the patients.

A presumptive diagnosis of TTP is made upon the demonstration of MAHA and thrombocytopenia in the absence of an alternative explanation. Although a severe deficiency of ADAMTS 13 protease (<10%) and the presence of an inhibitor to ADAMTS13 confirms the diagnosis of acquired TTP in the appropriate clinical setting, it is not essential for making the diagnosis, as its not 100% specific or sensitive [7]. Some patients with other causes of MAHA and thrombocytopenia can also have severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (e.g., in endocarditis or systemic malignancy) [14,15]. Thus, diagnosis should not be considered confirmed (or excluded) based solely upon ADAMTS13 activity. One study did show a sensitivity and specify of 100% for ADAMTS13 activity threshold of <10% for the diagnosis of TTP, but the sensitivity fell to approximately 95% when the threshold was lowered to <5% [16]. A mild to moderately low activity of ADAMTS13 (10–50%) occur in many hospitalized patients with inflammatory disorders, as well in patients with TTP who have received multiple transfusions. Normal ADAMTS13 activity (>50%) should prompt the clinician to look for causes of MAHA and thrombocytopenia other than TTP [11,17].

TTP is a medical emergency, and therapy should be started as soon as the presumptive diagnosis of TTP is made; it is almost always fatal if treatment with PEX is delayed [18–22]. Untreated TTP follows a natural course of progressive neurologic deterioration, cardiac ischemia, irreversible renal damage, and death. PEX has become the standard of treatment for TTP and it has reduced the mortality rate from an estimated 90% to less than 10% [19–22]. The addition of glucocorticoids and rituximab in select cases has further improved the survival and reduced duration of PEX [23]. Although randomized controlled trials are lacking, the usual standard approach is continuation of the PEX and glucocorticoids until the platelet count has been normal for at least 2 days. PEX is then gradually stopped, and glucocorticoids are slowly tapered off thereafter.

Patients with acquired TTP who have not shown a satisfactory response to treatment with PEX and glucocorticoids (defined as doubling of platelet count after 4 days of therapy), who have persistent disease, or who have an exacerbation of symptoms during PEX or within 30 days of stopping PEX and there is confidence in the diagnosis of TTP, are considered to have refractory TTP (30–40% of the patients).

Our patient did not show any improvement with PEX, glucocorticoids, and rituximab, and had a generalized tonic clonic seizure manifesting altered consciousness. Management of these patients, especially those who are critical (e.g., severely reduced platelet count or neurological abnormalities) is very challenging. They may need additional therapies for which there are no specific guidelines/recommendations and the evidence comes mainly from case reports. Agents that have been tried include cyclophosphamide, Bortezomib, Cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and N-acetylcysteine. Selection of an agent depends on the availability of the agent, patient age, and eligibility for a clinical trial.

We finally started our patient on cyclophosphamide due to her concomitant diagnosis of SLE, and she responded very well. She received 500 mg IV every 2 weeks for 6 cycles, and remains clinically stable with normal platelet count and other lab parameters after 2 months of follow-up.

Cyclophosphamide has been reportedly used as a salvage therapy in refractory disease and relapsing/chronic TTP, after therapy with vincristine, cyclosporine, and splenectomy (rarely performed nowadays) [24–26]. One study reported 18 patients with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (<10%), who did not improve with plasma exchanges, steroids, vincristine, and/or rituximab, and were considered for cyclophosphamide vs. splenectomy [27]. Thirteen patients underwent splenectomy 19 days after being diagnosed with TTP. One patient died. The remaining patients achieved durable PLT count in 13 days. Six patients experienced transient worsening of PLT count. Complications included infections (5 cases) and VTE (2 cases). Five patients received pulses of cyclophosphamide 12 days after being diagnosed with TTP. All patients achieved normal PLTs 10 days after the first pulse. Two patients experienced transient worsening and 2 had infections. Three relapses occurred in the splenectomy group at 5 months, 2.5 years, and 4.5 years, and 1 relapse occurred in the cyclophosphamide group at 3.5 years. Overall survival at 2.5 years was 94% [26].

Conclusions

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is a life-threatening hematological emergency which must be diagnosed and treated quickly. Refractory cases of TTP have been described in the literature, but without clear evidence-based guidelines for its management and solely based on expert opinion and previous case reports. Further studies are needed to establish guidelines for its management. We present this case to highlight the role that cyclophosphamide might have in these cases and to be a foundation for future studies.

References:

- 1.George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesher G, Hanna VE, Moore TL, et al. Thrombotic microangiographic hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;24(3):165–72. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song D, Wu LH, Wang FM, et al. The spectrum of renal thrombotic microangiopathy in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(1):R12. doi: 10.1186/ar4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musio F, Bohen EM, Yuan CM, Welch PG. Review of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in the setting of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;28(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuyama T, Kuwana M, Matsumoto M, et al. Heterogeneous pathogenic processes of thrombotic microangiopathies in patients with connective tissue diseases. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102(2):371–78. doi: 10.1160/TH08-12-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George JN, Vesely SK, James JA. Overlapping features of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and systemic lupus erythematosus. South Med J. 2007;100(5):512–14. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318046583f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood. 2010;116(20):4060–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-271445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reese JA, Muthurajah DS, Kremer Hovinga JA, et al. Children and adults with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with severe, acquired Adamts13 deficiency: Comparison of incidence, demographic and clinical features. pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(10):1676–82. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terrell DR, Vesely SK, Kremer Hovinga JA, et al. Different disparities of gender and race among the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic-uremic syndromes. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(11):844–47. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin D, Al-Nouri ZL, Muthurajah D, et al. First symptoms in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: what are they and when do they occur? Transfusion. 2013;53(1):235–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scully M, Yarranton H, Liesner R, et al. Regional UK TTP registry: Correlation with laboratory ADAMTS 13 analysis and clinical features. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(5):819–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins BM, Abu-Fadel M, Vesely SK, George JN. Clinical cardiac involvement in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review. Transfusion. 2008;48(2):382–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George JN, Chen Q, Deford CC, Al-Nouri Z. Ten patient stories illustrating the extraordinarily diverse clinical features of patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and severe ADAMTS13 deficiency. J Clin Apher. 2012;27(6):302–11. doi: 10.1002/jca.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieger M, Mannucci PM, Kremer Hovinga JA, et al. ADAMTS13 autoantibodies in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies and other immunomediated diseases. Blood. 2005;106(4):1262–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cataland SR, Wu HM. How I treat: the clinical differentiation and initial treatment of adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2014;123(16):2478–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-516237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan S, Westwood JP, Ellis D, et al. The utility of ADAMTS13 in differentiating TTP from other acute thrombotic microangiopathies: results from the UK TTP Registry. Br J Haematol. 2015;171(5):830–35. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amorosi EL, Ultmann JE. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: Report of 16 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1966;45:139–160. [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Baeyer H. Plasmapheresis in thrombotic microangiopathy-associated syndromes: Review of outcome data derived from clinical trials and open studies. Ther Apher. 2002;6(4):320–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2002.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(6):393–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, et al. British Committee for Standards in Haematology Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(3):323–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michael M, Elliott EJ, Ridley GF, et al. Interventions for haemolytic uraemic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD003595. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003595.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Som S, Deford CC, Kaiser ML, et al. Decreasing frequency of plasma exchange complications in patients treated for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome, 1996 to 2011. Transfusion. 2012;52(12):2525–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beloncle F, Buffet M, Coindre JP, et al. Thrombotic Microangiopathies Reference Center Splenectomy and/or cyclophosphamide as salvage therapies in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: The French TMA Reference Center experience. Transfusion. 2012;52(11):2436–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, Pallera AM, Goodnough LT, et al. Remission of chronic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after treatment with cyclophosphamide and rituximab. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(2):105–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-2-200301210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein GY, Zeidman A, Fradin Z, et al. Treatment of resistant thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with rituximab and cyclophosphamide. Int J Hematol. 2004;80(1):94–96. doi: 10.1532/ijh97.e0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]