Abstract

Thioredoxin (Trx) is a ubiquitous oxidoreductase maintaining protein-bound cysteine residues in the reduced thiol state. Here, we combined a well-established method to trap Trx substrates with the power of bacterial genetics to comprehensively characterize the in vivo Trx redox interactome in the model bacterium Escherichia coli. Using strains engineered to optimize trapping, we report the identification of a total 268 Trx substrates, including 201 that had never been reported to depend on Trx for reduction. The newly identified Trx substrates are involved in a variety of cellular processes, ranging from energy metabolism to amino acid synthesis and transcription. The interaction between Trx and two of its newly identified substrates, a protein required for the import of most carbohydrates, PtsI, and the bacterial actin homolog MreB was studied in detail. We provide direct evidence that PtsI and MreB contain cysteine residues that are susceptible to oxidation and that participate in the formation of an intermolecular disulfide with Trx. By considerably expanding the number of Trx targets, our work highlights the role played by this major oxidoreductase in a variety of cellular processes. Moreover, as the dependence on Trx for reduction is often conserved across species, it also provides insightful information on the interactome of Trx in organisms other than E. coli.

Thioredoxins (Trxs)1 are small antioxidant enzymes that catalyze the reduction of disulfide bonds that form in substrate proteins either as part of a catalytic cycle (see below) or following exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS). As such, Trxs are involved in many different cellular processes, ranging from the defense against oxidative stress to the regulation of numerous signal transduction pathways and the modulation of the inflammatory response (1, 2).

Trxs have been identified in most living organisms, including archaea, bacteria, plants and mammals (1). They all share a canonical WCGPC catalytic motif located on a highly conserved fold, which consists of five β-strands surrounded by four α-helices (Fig. 1A) (3). The cysteine residues of the WCGPC motif are the key players used by Trxs to break disulfide bonds in substrate proteins. In this reaction, the first cysteine performs a nucleophilic attack on an oxidized substrate, which results in the formation of a mixed-disulfide intermediate between Trx and its substrate. This intermediate is then resolved by a nucleophilic attack of the second cysteine of the WCGPC motif, leading to the oxidation of thioredoxin and the release of the reduced substrate (1) (Fig. 1B). The catalytic cysteine residues are then converted back to the reduced state by the flavoenzyme thioredoxin reductase at the expense of the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH).

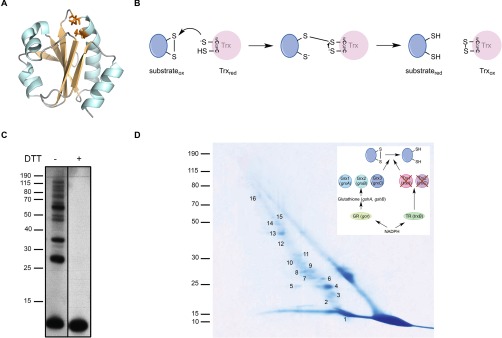

Fig. 1.

Trapping of Trx1 substrates in a ΔtrxAΔtrxC E. coli strain in vivo. A, Structure of reduced E. coli thioredoxin (PDB code: 1XOB). All thioredoxins share a canonical WCGPC catalytic motif located on a highly conserved fold, which consists of five β-strands (light orange) surrounded by four α-helices (cyan). The cysteines of the catalytic motif are represented in orange. The figure was generated using MacPyMol (Delano Scientific LLC 2006). B, Reaction mechanism of disulfide reduction by thioredoxin. The reaction takes off with a nucleophilic attack of the N-terminal cysteine of the conserved WCGPC motif targeting the disulfide. As a result, an intermediate mixed disulfide complex is formed between Trx and the substrate protein, which in turn is reduced by a nucleophilic attack of the C-terminal cysteine of the WCGPC motif. C, To trap proteins linked to Trx1, Trx1WCGPA was expressed in a ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant. The proteins were TCA-precipitated and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-His antibody. Induction of Trx1WCGPA led to the accumulation of several high-molecular weight complexes, which disappeared following addition of DTT. The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. D, The mixed-disulfide complexes were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose. After concentration, the proteins trapped by Trx1WCGPA were separated by SDS-PAGE (nonreducing dimension). The complexes were then separated in a second, reducing dimension. Proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. The spots analyzed by mass spectrometry were numbered as indicated (see Table I). The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. The inset shows the reducing pathway that was genetically modified. Here, by deleting the trxA and trxC genes, it is the Trx pathway that was impaired. Trx, thioredoxin; TR, thioredoxin reductase; Grx, glutaredoxin; gshA encodes the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase; gshB encodes the glutathione synthetase; GR, glutaredoxin reductase.

Escherichia coli Trx1, encoded by the gene trxA, is the first Trx that was discovered (4, 5). Being constitutively expressed in the cytoplasm, it reduces disulfide bonds that form during the catalytic cycle of important enzymes such as ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) (4), 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) reductase (6), the methionine sulfoxide reductases MsrA, MsrB and fRMsr (7–9), the inner membrane protein DsbD (10, 11), and the peroxidases Tpx (12) and BCP (13). In addition to its role in enzyme recycling, Trx1 also controls the redox state of proteins with cysteine residues prone to oxidation. When exposed to ROS, sensitive cysteines are first modified to sulfenic acids (-SOH), which then often react with another thiol present in the vicinity to form a disulfide (14). Being able to reduce both sulfenic acids and disulfides (1, 15), Trx1 plays an active role in the protection of proteins from oxidative damages. Differential thiol trapping experiments led to the identification of a handful of proteins that depend on this protective activity of Trx1 (16).

Although a number of proteins that interact with Trx1 have been identified using copurification experiments (17), a comprehensive survey of proteins that depend on this oxidoreductase for reduction is still missing. The goal of the present study was to fully grasp the importance of Trx1 in controlling the redox state of intracellular proteins by characterizing the redox interactome of this major oxidoreductase. A powerful approach to identify Trx substrates consists in trapping the covalent intermediates that form between this protein and its substrates when the second catalytic cysteine of the WCGPC motif is mutated to an alanine. In this case, dissociation of the mixed-disulfide intermediate is prevented, stabilizing the complexes between thioredoxin and its substrates (1). This approach, which has never been applied to E. coli Trx1, already led to the identification of putative Trx substrates in a variety of organisms, including Chlorobaculum tepidum and Synechocystis sp (18–21), algae and plants (22–34), parasites (35–37), and mammals (38). However, to our knowledge, in all studies carried out so far, the Trx mutants were used to capture potential target proteins in cellular extracts, being sometimes immobilized on a resin (18–20, 22–37). Hence, substrate trapping occurred in vitro. As proteins that normally do not get oxidized in vivo may become oxidatively damaged following cell lysis, in vitro trapping is likely to lead to the identification of nonphysiological targets. Moreover, if certain physiological substrates unfold following overoxidation during extract preparation, they may not be recognized by the Trx trapping mutant and will be missed.

In this study, we decided to take advantage of E. coli being easily amenable to genetic manipulation and protein expression to comprehensively identify the substrates of Trx1 in vivo. To that end, we expressed a Trx1WCGPA mutant in cells that were genetically engineered to optimize trapping by alteration of the cytoplasmic reducing pathways and that were exposed or not to an exogenous oxidative stress. This led us to the identification of a total of 268 putative substrates of Trx1, including 201 that had never been reported to depend on Trx for reduction and 78 that were found to interact with Trx1 only under severe oxidative stress conditions. Two of the new proteins involved in a disulfide complex with Trx1WCGPA, the bacterial actin homolog MreB and the protein involved in sugar import PtsI, were studied in more detail. Our study significantly expands the number of Trx targets, further highlighting the role played by this major oxidoreductase in a variety of cellular processes. The dependence of a given protein on the Trx system for reduction is usually conserved. For instance, RNR, MsrA, and MsrB are Trx substrates in organisms ranging from bacteria and fungi to plants and mammals (39). Therefore, our work also provides insightful information on the interactome of Trx in organisms other than E. coli.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Growth Conditions, and Plasmids

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1. Bacterial strains are E. coli MC4100 derivatives (40). All alleles, unless indicated, were moved by P1 transduction using standard procedures (41).

Strains IA195 and IA198, where ptsI was replaced by ptsIC502S or ptsIC272AC324MC575S on the chromosome, were constructed as follows. First, a cat-sacB cassette, encoding chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (cat) and SacB, a protein conferring sensitivity to sucrose, was amplified from strain CH1990 using primers ptsI-catsacB_Fw and ptsI-catsacB_Rv. The resulting PCR product shared a 40-bp homology to the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR of ptsI at its 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, and was used for lambda-red recombineering in strain IA186 as previously described (42). We verified that the cat-sacB cassette replaced the ptsI gene in the resulting strain (IA190) by sequencing across the junctions. The cat-sacB cassette was subsequently replaced by one of the mutated versions of ptsI (ptsIC502S or ptsIC272AC324MC575S) using the same technique. Briefly, ptsIC502S and ptsIC272AC324MC575S were amplified from plasmids pIA4 and pIA5 using primers catsacB-ptsI_Fw and catsacB-ptsIC502S_Rv, or catsacB-ptsI_Fw and catsacB-ptsIC272AC324MC575S_Rv, respectively, and the resulting PCR products were used for a second round of lambda-red recombineering in strain IA192 (IA190 transformed with pSIM5-Tet vector). Loss of the cassette in the resulting IA195 and IA198 strains was verified by positive (sucrose resistance) and negative (chloramphenicol sensitivity) selection and by PCR.

Unless indicated, bacteria were grown aerobically at 37 °C in LB medium. When necessary, growth media were supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml). For testing the ability to ferment glucose, MacConkey medium, supplemented with 0.5% glucose, was used.

Plasmid Constructions

The plasmids and primers used in the present study are listed in supplemental Tables S1 and S2. The pFB1 expression vector was constructed as follows. The region encoding trxA was amplified from the chromosome using primers Trx1_Fw and Trx1_Rv and inserted into the pHE43 vector restricted with NcoI and BglII (yciMHis was excised from the plasmid and replaced by trxA, allowing Trx1 to be His-tagged at the C terminus). The second cysteine of the WCGPC motif of Trx1 was mutated into an alanine by site-directed mutagenesis of pFB1 using primers Trx1WCGPA_Fw and Trx1WCGPA_Rv, generating plasmid pFB2. The pIA1 expression vector was constructed as follows. The region containing trxC was amplified from the chromosome using primers Trx2_Fw and Trx2_Rv and inserted into the pBAD-HisB vector restricted with NcoI and BglII. The second cysteine of the WCGPC motif of Trx2 was mutated into an alanine by site-directed mutagenesis of pIA1 using primers Trx2WCGPA_Fw and Trx2WCGPA_Rv, generating plasmid pIA2. The pIA3 expression vector was constructed as follows. ptsI was amplified from the chromosome using primers PtsI_Fw and PtsI_Rv and inserted into the pET28a vector. The cysteines of PtsI were mutated into serine, alanine, or methionine by site-directed mutagenesis of pIA3 using primers PtsIC502S_Fw and PtsIC502S_Rv, and primers PtsIC272A_Fw, PtsIC272A_Rv, PtsIC324M_Fw, PtsIC324M_Rv, PtsIC575S_Fw, and PtsIC575S_Rv, generating plasmids pIA4 and pIA5.

Trapping and Purification of Trx1WCGPA-substrate Complexes

Strains FB32, IA170 and IA370 were grown in one liter LB medium at 37 °C to reach an A600 of 0.5. Expression of Trx1WCGPAwas induced by addition of 0.2% l-arabinose. After 2 h, the culture was treated, or not, with 2 mm hypochlorous acid (HOCl) for 10 min and then precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and placed at 4 °C overnight. Cells were then centrifuged at 11,325 × g for 45 min. 50 ml of cold 5% TCA were added on the pellet and another centrifugation was performed at 17,696 × g for 20 min. The proteins were then resuspended in 25 ml of 100 mm NaPi pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 0.3% SDS, 8 m urea, and 10 mm iodoacetamide (IAM) to prevent any further disulfide bond rearrangement. The lysate was homogenized on a roller during 20 min and centrifuged at 23,708 × g for 45 min. The cleared lysate was finally diluted three times and loaded onto a 1 ml HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mm NaPi pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, and 0.3% SDS (buffer A). After washing with buffer A, proteins were eluted with a linear gradient from 0 to 300 mm imidazole in buffer A. Only one peak eluted from the column. This fraction was concentrated to 1.5 ml (using a Vivaspin Turbo 15 device (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany)) and proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions (first dimension). The gel lane was cut, incubated in 20 ml of a buffer containing 10% SDS, 0.3 m Tris pH 7.5, 100 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), and 50% glycerol for 1 h, and placed on top of a second SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were visualized with PageBlue Protein Staining Solution (Thermo Scientific).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Two-dimensional Gels

Spots of interest were excised from the SDS-PAGE gel, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by liquid chromatographic tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an LTQ XL as described (43). Briefly, peptides were separated by an acetonitrile gradient on a C18 column and the MS scan routine was set to analyze by MS/MS the five most intense ions of each full MS scan, dynamic exclusion was enabled to assure detection of coeluting peptides.

Protein identification was performed with SequestHT. In details, peak lists were generated using extract-msn (ThermoScientific) within Proteome Discoverer 1.4.1. From raw files, MS/MS spectra were exported with the following settings: peptide mass range 350–5000 Da, minimal total ion intensity 500. The resulting peak lists were searched using SequestHT against a target-decoy E. coli protein database obtained from Uniprot (July 30, 2015, 4339 entries). The following parameters were used: trypsin was selected with proteolytic cleavage only after arginine and lysine, number of internal cleavage sites was set to 1, mass tolerance for precursors and fragment ions was 1.0 Da, considered dynamic modifications were + 15.99 Da for oxidized methionine and +57.00 for carbamidomethyl cysteine. Peptide matches were filtered using the q-value and Posterior Error Probability calculated by the Percolator algorithm ensuring an estimated false positive rate below 5%. The filtered Sequest HT output files for each peptide were grouped according to the protein from which they were derived and their individual number of peptide spectral matches was taken as an indicator of protein abundance. The obtained data can be found in supplemental Tables S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, and S8. To build Tables I, supplemental Tables S9, and S10, we selected the cysteine-containing proteins for which at least two peptides were found in two independent experiments (data from supplemental Tables S3 and S4 were used to build Table I, data from supplemental Tables S5 and S6 were used to build supplemental Table S9, and data from supplemental Tables S7 and S8 were used to build supplemental Table S10). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (44) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD003098 (username: reviewer30780@ebi.ac.uk, with password:0gnlCrwC).

Table I. Thioredoxin targets identified in a ΔtrxAΔtrxC E. coli strain. The proteins in this table were identified in two independent experiments with at least two peptides found in the indicated spot. They all contain cysteine residues. The full list of identified proteins for Experience 1 can be found in Table S3 and those for Experience 2 in Table S4. #PSM, number of peptide-spectrum matches; #pept, number of peptides; #cys, number of cysteines; MW, molecular weight. See supplemental Fig. S4A for the gel of Experience 2.

| Gene | Uniprot ID | Description | Experience 1 |

Experience 2 |

#cys | MW (kDa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spot | #PSM | #pept | spot | #PSM | #pept | |||||

| Energy metabolism | ||||||||||

| ATP-proton motive force interconversion | ||||||||||

| atpAb,c | P0ABB0 | ATP synthase subunit alpha | 15 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 55.2 |

| atpDb,c | P0ABB4 | ATP synthase subunit beta | 14 | 44 | 22 | 12 | 17 | 13 | 1 | 50.3 |

| atpGb | P0ABA6 | ATP synthase gamma chain | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 31.6 |

| nuoE | P0AFD1 | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit E | 4 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 18.6 |

| Glycolysis | ||||||||||

| fbaAb,c | P0AB71 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase class 2 | 12 | 18 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 39.1 |

| gapAb,c | P0A9B2 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A | 11 | 13 | 7 | 9 | 33 | 10 | 3 | 35.5 |

| lpdA | P0A9P0 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | 15 | 24 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 50.7 |

| pfkAb | P0A796 | ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase isozyme 1 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 34.8 |

| pgkb | P0A799 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 13 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 23 | 13 | 3 | 41.1 |

| pykFb,c | P0AD61 | Pyruvate kinase I | 15 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 50.7 |

| Gluconeogenesis | ||||||||||

| sdaA | P16095 | l-serine dehydratase 1 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 48.9 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | ||||||||||

| gndb | P00350 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | 13 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 2 | 51.4 |

| talBb,c | P0A870 | Transaldolase B | 11 | 23 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 3 | 35.2 |

| TCA cycle | ||||||||||

| gltAb | P0ABH7 | Citrate synthase | 14 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 48 |

| icdb,c | P08200 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP] | 14 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 45.7 |

| mdhb | P61889 | Malate dehydrogenase | 10 | 25 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 13 | 3 | 32.3 |

| sucCb,c | P0A836 | Succinyl-CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit beta | 13 | 18 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 41.4 |

| sucDb,c | P0AGE9 | Succinyl-CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit alpha | 9 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 29.8 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism (other) | ||||||||||

| ackA | P0A6A3 | Acetate kinase | 13 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 43.3 |

| aldA | P25553 | Lactaldehyde dehydrogenase | 15 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 52.2 |

| deoB | P0A6K6 | Phosphopentomutase | 13 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 44.3 |

| deoC | P0A6L0 | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase | 8 | 62 | 14 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 27.7 |

| galF | P0AAB6 | UTP–glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | 10 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 32.8 |

| garR | P0ABQ2 | 2-hydroxy-3-oxopropionate reductase | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30.4 |

| gatY | B1X7I7 | Tagatose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase GatY | 9 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 22 | 6 | 4 | 30.8 |

| gatZ | P0C8J8 | Putative tagatose 6-phosphate kinase GatZ | 14 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 47.1 |

| glpK | P0A6F3 | Glycerol kinase | 15 | 9 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 56.2 |

| nanA | P0A6L4 | N-acetylneuraminate lyase | 10 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 32.6 |

| Processes | ||||||||||

| Cell division/cellular structure | ||||||||||

| mreBc | P0A9X4 | Rod shape-determining protein MreB | 12 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 36.9 |

| Chaperones | ||||||||||

| groLb | P0A6F5 | 60 kDa chaperonin | 16 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 57.3 |

| Detoxification/oxidative stress response | ||||||||||

| ahpCb | P0AE08 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C | 4 | 136 | 16 | 6 | 175 | 13 | 2 | 20.7 |

| bcpa,b | P0AE52 | Putative peroxiredoxin bcp | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 17.6 |

| katGb,c | P13029 | Catalase-peroxidase | 16 | 10 | 9 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 80 |

| msrBa,b | P0A746 | Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase MsrB | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 15.4 |

| msrCa,b | P76270 | Free methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase | 3 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 18.1 |

| sodB | P0AGD3 | Superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 4 | 20 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 21.3 |

| tpxa,b,c | P0A862 | Thiol peroxidase | 3 | 41 | 10 | 4 | 139 | 8 | 3 | 17.8 |

| trxBa,b | P0A9P4 | Thioredoxin reductase | 10 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 34.6 |

| ucpA | P37440 | Oxidoreductase UcpA | 9 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 27.8 |

| Regulatory functions | ||||||||||

| arcA | P0A9Q1 | Aerobic respiration control protein ArcA | 8 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 27.3 |

| furc | P0A9A9 | Ferric uptake regulation protein | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 16.8 |

| Transport/binding proteins | ||||||||||

| araG | P0AAF3 | Arabinose import ATP-binding protein AraG | 15 | 5 | 4 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 55 |

| ppab | P0A7A9 | Inorganic pyrophosphatase | 4 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19.7 |

| Small molecules biosynthesis and degradation | ||||||||||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | ||||||||||

| aspA | P0AC38 | Aspartate ammonia-lyase | 15 | 5 | 5 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 52.3 |

| cysKb | P0ABK5 | Cysteine synthase A | 11 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 34.5 |

| glnAb | P0A9C5 | Glutamine synthetase | 15 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 51.9 |

| glyAb | P0A825 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | 13 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 45.3 |

| iscS | P0A6B7 | Cysteine desulfurase IscS | 13 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 45.1 |

| metKb | P0A817 | S-adenosylmethionine synthase | 13 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 41.9 |

| Amino acid degradation | ||||||||||

| tnaAb,c | P0A853 | Tryptophanase | 14 | 53 | 22 | 12 | 67 | 18 | 7 | 52.7 |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | ||||||||||

| accC | P24182 | Biotin carboxylase | 14 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 49.3 |

| fabAc | P0A6Q3 | 3-hydroxydecanoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase | 2 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| fabB | P0A953 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase 1 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 42.6 |

| fabDb | P0AAI9 | Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase | 10 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 32.4 |

| fabH | P0A6R0 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 33.5 |

| fabZc | P0A6Q6 | 3-hydroxyacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase FabZ | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 17 |

| Deoxyribonucleotide/nucleoside metabolism | ||||||||||

| cddb | P0ABF6 | Cytidine deaminase | 9 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 31.5 |

| Purine/pyrimidine ribonucleotide biosynthesis | ||||||||||

| preT | P76440 | NAD-dependent dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase subunit PreT | 13 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 44.3 |

| prs | P0A717 | Ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase | 10 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 34.2 |

| purAb | P0A7D4 | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | 13 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 47.3 |

| Salvage of nucleotides and nucleosides | ||||||||||

| deoA | P07650 | Thymidine phosphorylase | 14 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 47.2 |

| Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis | ||||||||||

| moaB | P0AEZ9 | Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein B | 2 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18.7 |

| Iron-sulfur cluster assembly | ||||||||||

| iscUb | P0ACD4 | Iron-sulfur cluster assembly scaffold protein IscU | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 13.8 |

| Macromolecules | ||||||||||

| DNA transcription | ||||||||||

| hns | P0ACF8 | DNA-binding protein H-NS | 1 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 15.5 |

| rho | P0AG30 | Transcription termination factor Rho | 14 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 47 |

| Protein translation and modification | ||||||||||

| asnS | P0A8M0 | Asparagine–tRNA ligase | 14 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 52.5 |

| gltX | P04805 | Glutamate–tRNA ligase | 15 | 12 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 53.8 |

| hisS | P60906 | Histidine—tRNA ligase | 14 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 47 |

| infC | P0A707 | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 20.6 |

| prfB | P07012 | Peptide chain release factor 2 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 41.2 |

| rplB | P60422 | 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 29.8 |

| rplE | P62399 | 50S ribosomal protein L5 | 3 | 64 | 15 | 4 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 20.3 |

| rplFb | P0AG55 | 50S ribosomal protein L6 | 3 | 30 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 18.9 |

| rplJ | P0A7J3 | 50S ribosomal protein L10 | 1 | 23 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 17.7 |

| rplK | P0A7J7 | 50S ribosomal protein L11 | 1 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 14.9 |

| rplN | P0ADY3 | 50S ribosomal protein L14 | 1 | 22 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13.5 |

| rplQ | P0AG44 | 50S ribosomal protein L17 | 1 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 14.4 |

| rpsAb | P0AG67 | 30S ribosomal protein S1 | 16 | 60 | 28 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 61.1 |

| rpsBb | P0A7V0 | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | 8 | 42 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 26.7 |

| rpsKb | P0A7R9 | 30S ribosomal protein S11 | 1 | 17 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13.8 |

| rpsLb | P0A7S3 | 30S ribosomal protein S12 | 1 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 13.7 |

| rpsM | P0A7S9 | 30S ribosomal protein S13 | 1 | 29 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 13.1 |

| serS | P0A8L1 | Serine–tRNA ligase | 15 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 48.4 |

| tsfc | P0A6P1 | Elongation factor Ts | 10 | 35 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 30.4 |

| tufBb | P0CE48 | Elongation factor Tu | 13 | 99 | 20 | 11 | 87 | 17 | 3 | 43.3 |

| t-RNA and r-RNA processing | ||||||||||

| miaB | P0AEI1 | tRNA-2-methylthio-N(6)-dimethylallyladenosine synthase | 15 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 53.6 |

| mnmA | P25745 | tRNA-specific 2-thiouridylase MnmA | 13 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 40.9 |

| ATP binding | ||||||||||

| ychF | P0ABU2 | Ribosome-binding ATPase YchF | 13 | 26 | 15 | 11 | 37 | 14 | 6 | 39.6 |

| Protein degradation/proteases | ||||||||||

| clpXb | P0A6H1 | ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit ClpX | 14 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 46.3 |

| pepD | P15288 | Cytosol non-specific dipeptidase | 15 | 8 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 52.9 |

| Unknown proteins | ||||||||||

| yfeX | P76536 | Probable deferrochelatase/peroxidase YfeX | 10 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 33 |

Impact of Thioredoxin Deletion on MreB Distribution in Living Cells Upon A22 Treatment

Strains IA90, IA94, IA396, and IA398 were grown in LB medium at 30 °C to reach an A600 of 0.5. S-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl) isothiourea (A22) was then added at a concentration of 5 μg/ml and growth was continued for 2 h. For complementation studies, expression of Trx1 in trans in IA396 was induced by addition of 0.2% l-arabinose when cells reached an A600 of 0.1.

Microscopy Image Acquisition

Cells were spotted on PBS + 1% agarose pads between a glass slide and a coverslip. Imaging was performed using an Axio Observer.Z1 inverted epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen Germany) equipped with an AxioCam 506 mono camera (Carl Zeiss), 1x/C-mount camera adaptor (Carl Zeiss), phase contrast objective Plan Apochromat 100×/1.40 Oil Ph3 (Carl Zeiss), and filter set 31 (Carl Zeiss) to image RFP-associated fluorescence. Images were acquired using the ZEN2012 (blue edition) software (Carl Zeiss) and processed with MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Exposure times were identical for compared conditions.

Determination of MreB In Vivo Redox State by Reverse Trapping

Strains JAS27 and FB30 were grown in LB medium at 37 °C to reach an A600 of 0.5. H2O2 was then added at a concentration of 1 mm and growth was continued for 30 min. At several time-points, 1.8 ml of culture were precipitated with 10% TCA. Samples were then incubated on ice for 20 min and centrifuged at 16,100 × g for 5 min. The resulting pellets were washed with 400 μl ice-cold acetone and resuspended in 100 μl denaturing buffer (6 m urea, 200 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 10 mm EDTA) supplemented with 100 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). After a 20 min incubation at 25 °C and with 600 rpm shaking, the reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of 10% TCA and left on ice for 20 min. The NEM-modified proteins were centrifuged and the pellet washed as described above. The proteins were then dissolved in 100 μl of 10 mm DTT in denaturing buffer. After a 1 h incubation at 25 °C and with 1400 rpm shaking, the reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of 10% TCA and left on ice for 20 min. The reduced proteins were centrifuged and the pellet washed as above. The proteins were then dissolved in 30 μl of 1× sample buffer (2% SDS, 12% glycerol, 60 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.01% bromphenol blue) containing 2 mm of methoxyl polyethylene glycol maleimide (MalPEG) 2 kDa. After a 1 h incubation at 37 °C and with 1400 rpm shaking in the dark, samples were diluted three times in 1× sample buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions and MreB was detected by Western blotting using an anti-MreB antibody.

Identification of the MreB Cysteine Involved in the MreB- Trx1WCGPA Interaction by LC-MS/MS

Recombinant MreB (5 μg), expressed and purified as in (45), was incubated with Trx1WCGPA (1.6 μg) for 1 h on ice, in 200 μl of a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.1 mm EDTA, 100 mm KCl, and 20% glycerol. Proteins were then precipitated with 10% TCA after 10 μg of bovine serum albumin were added as a carrier. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of 100 mm NH4HCO3 pH 8.0 and the proteins digested overnight at 30 °C with 0.5 μg of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI). The peptides were analyzed by capillary LC-MS/MS in a LTQ XL ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA), fitted with a microelectrospray probe. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode and switched automatically between MS, Zoom Scan for charge state determination and MS/MS for the five most abundant ions. Peptides were identified by Sequest and the mixed disulfide between MreB and Trx1WCGPA was identified using DBond (46). The modified peptides were manually validated.

PtsIAMCS Expression and Purification

BL21 (DE3) competent cells were transformed with plasmid pIA5, yielding strain IA160. During overnight cultures in LB medium containing 200 μg/ml of ampicillin at 37 °C without shaking, cells reached an A600 nm of ∼0.5. Cells were then cultured aerobically with shaking (200 rpm) at 37 °C. After 30 min, protein expression was induced by adding 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (2800 × g, 4 °C, 20 min) after 3 h of induction. Cells were resuspended in 10 ml buffer A containing 50 mm NaPi pH 8.0 and 300 mm NaCl and disrupted by two passages through a French press (1500 psi). The cell lysate was then centrifuged during 40 min (23,600 × g, 4 °C). Supernatant was recovered and diluted about 3 times in buffer A and filtered with a Minisart High-Flow filter (Sartorius, pores of 0.2 μm diameter). The diluted supernatant was loaded on a HisTrap FF (1 ml, GE Healthcare) at 1 ml/min. After washing the column, proteins were eluted using an imidazole gradient (0 to 180 mm in buffer A). The fractions containing PtsIAMCS were concentrated using a Vivaspin Turbo 15 device (Sartorius) and desalted on a PD-10 column (GE healthcare) equilibrated with buffer B (50 mm NaPi pH 8.0 and 150 mm NaCl). PtsIAMCS was then reloaded on an affinity chromatography column to reach a higher degree of purity (using the same protocol as described above).

Identification of the Dimedone-modified Peptide of PtsI by LC-MS/MS

Recombinant PtsIAMCS (10 μg) was incubated for 5 min at room temperature in the presence of 5 mm dimedone (DMD). The sample was then incubated with 2 mm H2O2 for 15 min, and then treated with 50 mm IAM for 10 min at room temperature to block reduced thiols. The protein was then precipitated with 10% TCA and the pellet resuspended in 50 μl of 100 mm NH4HCO3 pH 8.0, for overnight digestion at 30 °C with 0.5 μg of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI). The peptides were analyzed by capillary LC-MS/MS in a LTQ XL ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific), fitted with a microelectrospray probe. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode and switched automatically between MS, Zoom Scan for charge state determination and MS/MS for the five most abundant ions. Peptides were identified by Proteome Discoverer software (Thermo Scientific, version 1.4.0.288) considering dynamic modifications on cysteine residues of 138.0 Da for sulfenic dimedone. Modified peptides were manually validated.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

In order to reliably identify proteins forming mixed-disulfides with Trx, all trapping experiments (in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant, with or without HOCl, and in the ΔtrxAΔgshA mutant) were performed in biological duplicates. To prevent oxidation of cysteine residues as well as the disulfide rearrangements that could potentially occur following cells lysis, cellular samples were prepared by directly adding 10% TCA to the cells growing in culture media. This acidic treatment not only denatures cellular proteins but also ensures that the reduced cysteine residues become protonated and therefore poorly reactive. In addition, IAM was added to the buffer used to resuspend the precipitated proteins prior to the diagonal gel analysis. IAM covalently modifies reduced cysteine residues, therefore blocking the thiol-disulfide exchange reactions that could occur when the sample is brought to the more alkaline pH of the resuspension buffer (pH 8).

The complexes involving Trx1WCGPA bound to its substrates were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose. Untagged proteins nonspecifically binding to the column were also eluted when the imidazole gradient was applied. However, as these contaminants are not involved in a mixed disulfide complex, they are separated according to molecular weight in both the nonreducing and reducing dimensions of the diagonal gel. They migrate therefore on a diagonal in the second dimension, in contrast to the Trx substrates, allowing the discrimination between the Trx interacting partners and the nonspecific contaminants.

To build Table I, supplemental Tables S9, and S10, the data were filtered to include only proteins containing cysteine residues and for which at least two peptides were found in the biological duplicates.

The procedures carried out to probe the in vivo redox state of MreB in the wild type and in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant were done in biological triplicates as well as the microscopy experiments performed to investigate the physiological importance of the Trx system in MreB function. All the tests aiming at determining the importance of the cysteine residues of PtsI were also done in biological triplicates.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of Trx1 Targets In Vivo

To trap E. coli Trx1 bound to its substrates, we used a mutant version of the protein lacking the second cysteine of the catalytic site and fused to a C-terminal His-tag (Trx1WCGPA). This mutant was expressed in a strain in which the Trx system had been disrupted by deletion of both trxA (encoding Trx1) and trxC (encoding Trx2, an atypical, less abundant, thioredoxin (47–49); see below) in order to optimize trapping. As shown in Fig. 1C, induction of Trx1WCGPA expression led to the formation of several high-molecular weight complexes recognized by the anti-His antibody. These complexes were DTT-sensitive, indicating that they corresponded to Trx1WCGPA bound to unknown proteins via a disulfide. Trx1WCGPA and its covalently-bound partners were then purified by affinity chromatography. Only one peak eluted from the column when an imidazole gradient was applied (not shown). The purified sample was then analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, in which the first dimension is nonreducing whereas the second is reducing (50–52). In this experiment, proteins that were not linked to Trx1WCGPA by a disulfide bond were separated according to molecular weight in both dimensions and were therefore found on a diagonal in the second dimension. In contrast, proteins that were in complex with Trx1WCGPA were separated from it under the reducing conditions of the second dimension and were found off the diagonal (Fig. 1D). These proteins were subjected to MS/MS analysis and identified. Ninety-one cysteine-containing proteins for which at least two peptides were reproducibly found off the diagonal in two independent experiments were considered as putative Trx1 substrates (Table I, constructed from supplemental Tables S3 and S4). These proteins included several well-known Trx1 targets such as the enzymes Tpx, BCP, MsrB, and fRMsr, nicely validating our data. As expected, given the conservation of the Trx interactome across species, the list of Trx1 substrates also included 40 proteins that had been shown to interact with Trx in organisms other than E. coli (Table I). Remarkably, 51 proteins that were released from Trx1WCGPA in the second dimension had never been reported to depend on the Trx system for reduction in any organism. The new thioredoxin targets are involved in a variety of cellular and metabolic processes, including ATP production, glycolysis, carbohydrate metabolism, protein translation, iron-sulfur cluster assembly, and protein homeostasis (see Table I). Unlike enzymes such as Tpx and MsrB that form a disulfide bond during catalysis and depend on Trx for recycling, most of the newly identified Trx substrates are well-characterized proteins that have not been reported to form catalytic disulfides. However, the fact that they were trapped in a mixed-disulfide complex with Trx1WCGPA implies that these proteins become Trx1 targets following the oxidation of at least one sensitive cysteine residue, most likely to a sulfenic acid possibly rearranging into a disulfide. In agreement with this, several of the identified Trx substrates have been reported to contain redox-sensitive cysteine residues, such as pyruvate kinase I (pykF) (53, 54), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapA) (55–58), isocitrate dehydrogenase (icd) (59–61), malate dehydrogenase (mdh) (62–65), and tryptophanase (tnaA) (66–68). In addition, other newly identified Trx substrates, such as aspartate ammonia-lyase (aspA) (69, 70), biotin carboxylase (accC) (71–73), ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase (prs) (74, 75), ferric uptake regulation protein (fur) (76), and 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase 1 (fabB) (77), contain cysteine residues that are important for activity, suggesting that Trx1 is involved in maintaining them active.

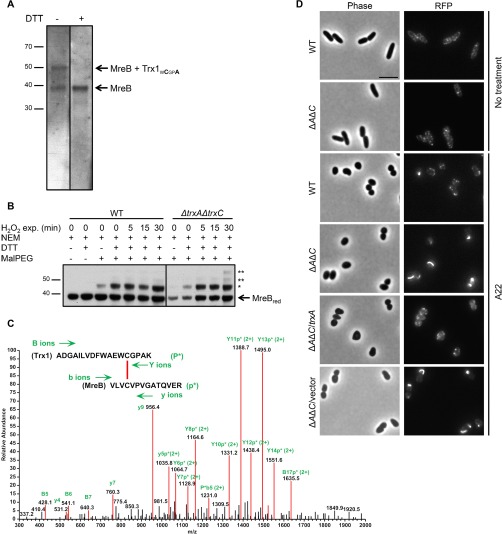

The Actin Homolog MreB is a Trx1 Substrate

We were intrigued by the identification of the actin structural homolog MreB as a putative Trx1 substrate. MreB is a major rod-shape determinant in E. coli and many other nonspherical bacteria (78). It forms discrete patches underneath the cell membrane that move around the cell circumference, in a manner that requires cell wall synthesis (79–81). In the presence of ATP or GTP, MreB polymerizes and forms small antiparallel double filaments (78). As shown in supplemental Fig. S1A, E. coli MreB has three cysteine residues, two of which (Cys113 and Cys324) are conserved in homologous proteins ranging from the α, β, γ-proteobacteria, to Bacilli and Clostridia. Although the conserved cysteines do not seem to be required for MreB function (78, 82–84), they are present in the nucleotide-binding pocket (supplemental Fig. S1B) where their oxidation would likely impair nucleotide binding and inhibit MreB (85). The important role played by MreB in rod-shaped bacteria prompted us to further investigate its redox sensitivity and interaction with Trx1. First, we confirmed that Trx1 (12 kDa) and MreB (36 kDa) form a DTT-sensitive 48 kDa mixed-disulfide complex in vivo, using a specific anti-MreB antibody (Fig. 2A). We then carried out reverse thiol trapping experiments (16) in order to determine if MreB can become oxidized in vivo, as implied by the identification of the Trx1-MreB complex. In this approach, all reduced cysteine residues are first covalently modified with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). Oxidized cysteines are then reduced with DTT and subsequently alkylated with MalPEG. MalPEG is a 2 kDa molecule that modifies free thiols leading to a major shift on SDS-PAGE. As seen in Fig. 2B, we found that a slow-migrating band of ∼45 kDa appears when samples from both the wild type and the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant are treated with MalPEG, indicating that MreB can be oxidized in vivo. In addition, exposure of cells to H2O2, an oxidizing agent, led to the appearance of two additional higher-migrating bands in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant but not in the wild type, which indicates that MreB is further oxidized when the Trx system is impaired. It is difficult to accurately predict the number of modified cysteine residue(s) from the migration of MalPEG-modified proteins in SDS-PAGE and attempts to identify the MreB cysteines getting oxidized in vivo failed. However, MS analysis of purified, air-oxidized MreB led to the identification of a disulfide bond between Cys113 and Cys324, the two cysteine residues found in the nucleotide binding pocket (not shown). Furthermore, LC-MS/MS analysis of the Trx1-MreB complex reconstituted in vitro using purified proteins identified Cys113 of MreB as the cysteine involved in the mixed-disulfide with Trx1WCGPA (Fig. 2C). Altogether, these results reveal that the cytoskeletal protein MreB contains cysteine residues that are susceptible to oxidation. They also involve Trx1 in the recycling of MreB and suggest that the activity of MreB is redox-regulated.

Fig. 2.

The actin homolog MreB is a Trx1 substrate. A, After expression of Trx1WCGPA in a ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant and purification and concentration of the complexes, the elution fraction was analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-MreB antibody. The bands corresponding to MreB alone or in complex with Trx1WCGPA are indicated. Upon DTT addition, the band corresponding to the complex disappeared whereas the MreB band increased, indicating that Trx1WCGPA is released from MreB under reducing conditions. The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. The fact that MreB was observed in the nonreduced sample indicates that a portion of this protein co-purified with Trx1WCGPA on the Ni-NTA agarose column. B, To determine if MreB can become oxidized in vivo, a reverse thiol trapping experiment was performed in a wild-type (WT) strain and a ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant strain. All reduced cysteine residues were first covalently modified with NEM. Oxidized cysteines are then reduced with DTT and subsequently alkylated with MalPEG. MalPEG modifies free thiols leading to a major shift on SDS-PAGE. Samples were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-MreB antibody. The band corresponding to reduced MreB (MreBred) is indicated. Upon MalPEG addition, a slow-migrating band (*) appears when samples from both the wild type and the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant are treated, indicating that MreB can be oxidized in vivo. Exposure (exp.) of cells to 1 mm H2O2 led to the appearance of two additional higher migrating bands (**) in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant but not in the wild type, which indicates that MreB is further oxidized when the Trx system is impaired. The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. Both parts of the figure come from a single membrane. C, Trx1WCGPA forms a mixed disulfide complex with MreB. Mass spectrometry analysis of a triply charged parent ion of [M+3H]3+ = 1139.3 Da shows fragmentation characteristics of a disulfide linkage between Cys33 of Trx and Cys113 of MreB, as determined by the DBond software (46). P*, one strand of a dipeptide; p*, the other strand of a dipeptide; capital letters, fragment ions from peptide P*; lowercase letters, fragment ions from peptide p*. D, Wild-type (WT) and ΔtrxAΔtrxC (ΔAΔC) cells expressing an MreB-RFP-MreB sandwich fluorescent fusion were observed using phase contrast (left) and fluorescence microscopy (right). MreB localized similarly in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant and in the wild type when cells were grown under normal conditions. Upon A22 treatment, an abnormal MreB localization pattern was observed in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC double mutant but not in the wild type. Expression of Trx1 (but not of the empty plasmid) in trans restored an MreB normal localization pattern. Bar, 5 μm.

To further investigate this unsuspected link between redox homeostasis and cell shape, we transduced a functional mreB-RFP-mreB sandwich fluorescent fusion (86) at the native mreB chromosomal locus in wild-type and ΔtrxAΔtrxC cells. As shown in Fig. 2D, we found no difference of MreB localization between the ΔtrxAΔtrxC mutant and the wild type when cells were grown under normal conditions. However, upon sub-lethal addition of S-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl) isothiourea (A22), a widely used MreB inhibitor targeting the active site (83), an abnormal MreB localization pattern was observed in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC double mutant but not in the wild type (Fig. 2D). Expression of Trx1 in trans restored MreB localization in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC double mutant (Fig. 2D). Thus, these data support the idea that Trx1 protects MreB from oxidative damages, possibly the formation of a disulfide bond in the nucleotide-binding pocket.

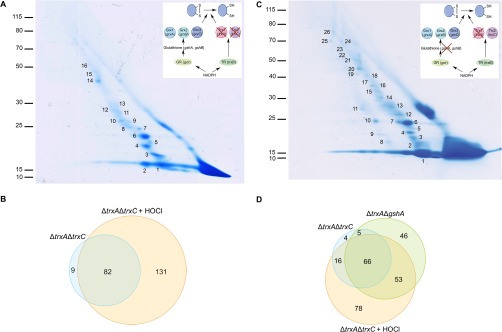

Probing the Impact of Exogenous Oxidative Stress on the Trx Interactome

The fact that the proteins listed in Table I were found in complex with Trx1 implies that they contain cysteine residues prone to oxidation, probably by the ROS endogenously produced by E. coli (87). This prompted us to test if exposure of cells to an exogenous more severe oxidative stress would lead to the identification of additional Trx substrates. To that end, we expressed the Trx1WCGPA variant in ΔtrxAΔtrxC cells grown in LB. When the culture reached an A600 of 0.5, HOCl was added. HOCl is a fast acting oxidant released by neutrophils to kill invading bacteria and reacting most rapidly with cysteine and methionine residues (88, 89), causing oxidative protein unfolding and the formation of incorrect disulfide bonds. The complexes involving Trx1WCGPA were purified by affinity chromatography and subjected to diagonal gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3A), as described above. Following MS/MS analysis, we identified 213 proteins that were found in a mixed-disulfide complex with Trx1WCGPA (they were off the diagonal) in two independent experiments (supplemental Table S9, constructed from supplemental Tables S5 and S6). Eighty-two of the 213 identified proteins had already been found covalently-bound to Trx1WCGPA in the experiment performed without HOCl (Fig. 3B), which validates the data shown in Table I. The 131 remaining proteins were only found in complex with Trx1WCGPA when an oxidative stress was applied. Interestingly, the new Trx substrates include several proteins involved in the defense mechanisms against oxidative stress, such as the peroxiredoxin OsmC (90, 91), the transcription factor OxyR (92–94), and the methionine sulfoxide reductase MsrA (95, 96), a well known Trx substrate. Of note, 112 of the newly identified Trx1 partners had never been reported to interact with thioredoxin in any living organism. These proteins are involved in a variety of cellular functions including energy metabolism, amino acid synthesis, cell division, lipopolysaccharide synthesis, protein homeostasis, and transcription (see supplemental Table S9). These data highlight the important role played by Trx1 in rescuing a large number of proteins damaged by oxidative stress.

Fig. 3.

Trapping of Trx1 substrates in a ΔtrxAΔtrxC E. coli strain in the presence of HOCl and in a in a ΔtrxAΔgshA E. coli strain in vivo. A, To identify Trx1 substrates upon oxidative stress, ΔtrxAΔtrxC cells expressing Trx1WCGPA were exposed to HOCl for 10 min. The mixed-disulfide complexes were then purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose. After concentration, the proteins trapped by Trx1WCGPA were separated by SDS-PAGE (nonreducing dimension). The complexes were then separated in a second, reducing dimension. Proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. The spots analyzed by mass spectrometry were numbered as indicated (see supplemental Table S9). The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. The inset shows the reducing pathway that was genetically modified. Here, by deleting the trxA and trxC genes, it is the Trx pathway that was impaired. Trx, thioredoxin; TR, thioredoxin reductase; Grx, glutaredoxin; gshA encodes the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase; gshB encodes the glutathione synthetase; GR, glutaredoxin reductase. B, Venn diagram representing the numbers of proteins identified in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC strain with or without HOCl stress (from Tables I and supplemental Table S9). C, To identify the Trx1 substrates that may have been missed because of the activity of the Grx pathway, Trx1WCGPA was expressed in a ΔtrxAΔgshA mutant. The mixed-disulfide complexes were then purified, concentrated and separated as described in A. Proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. The spots analyzed by mass spectrometry were numbered as indicated (see supplemental Table S10). The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. The inset shows the reducing pathways that were genetically modified. Here, by deleting the trxA and gshA genes, both the Trx and the Grx pathways were impaired. Legend is the same as in A. D, Venn diagram representing the numbers of proteins identified in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC (with HOCl stress or not) and the ΔtrxAΔgshA strains (from Tables I, S9 and S10).

Engineering E. coli to Optimize Trapping

The fact that PAPS reductase and the catalytic subunit of RNR (subunit alpha), two major Trx substrates (4, 6), were not found in complex with Trx1WCGPA, even when an exogenous oxidative stress was applied, indicated that certain Trx targets had managed to escape the hunt. We reasoned that this could be because of the activity of the glutathione/glutaredoxin (Grx) pathway, a reducing system functioning in parallel to the Trx pathway in the E. coli cytosol. In the Grx pathway, electrons flow from NADPH to glutathione via glutathione oxidoreductase and then from glutathione to three dithiol glutaredoxins (6, 97, 98), some of which share a partially redundant substrate specificity with Trx1. Therefore, in order to identify Trx1 substrates that may have been missed because of their reduction by the Grx pathway, we decided to proceed with the trapping experiment in cells where both reducing pathways are impaired. Although E. coli, like many other bacteria, needs either the Trx or Grx pathway for survival (99, 100), strains with partially functioning pathways can be engineered (100). For instance, cells lacking trxA and gshA, encoding an enzyme required for glutathione biosynthesis, are blocked for the Grx pathway and do not express Trx1 but remain viable because of the presence of Trx2. We decided to use these cells to search for additional Trx1 substrates. Indeed, as Trx2 has a limited substrate specificity, which we showed using a Trx2WCGPA mutant (supplemental Fig. S2), ΔtrxAΔgshA cells are likely to accumulate most Trx1 substrates in the oxidized state, even those that can otherwise be reduced by the Grx pathway, making these cells ideally suited for this search.

The Trx1WCGPA variant was expressed in ΔtrxAΔgshA cells, purified by affinity chromatography and subjected to diagonal gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3C) as described before. MS/MS analysis led to the identification of 170 proteins that were found in a mixed-disulfide complex with Trx1WCGPA in two independent experiments (supplemental Table S10, constructed from supplemental Tables S7 and S8). Almost half of the identified proteins (71 out of 170) had already been found covalently-bound to Trx1WCGPA when this protein was expressed in the ΔtrxAΔtrxC strain (Fig. 3D), further validating the data shown in Table I. Remarkably, expressing Trx1WCGPA in ΔtrxAΔgshA cells led to the identification of 99 additional proteins that were released from Trx1WCGPA in the second dimension, 82 of which had never been reported to interact with thioredoxin in any living organism. The new putative Trx1 substrates are involved in a variety of cellular functions ranging from energy metabolism, amino acid synthesis, protein homeostasis to transcription (see supplemental Table S10). They also included the enzymes RNR (catalytic subunit alpha) and PAPS reductase, in agreement with our starting hypothesis, and strongly suggesting that some of the new Trx1 substrates identified in ΔtrxAΔgshA cells possess oxidation-prone cysteine residue(s) that can be reduced by both cytoplasmic reducing pathways. It is also interesting to note that 53 out of the 99 substrates identified in the ΔtrxAΔgshA mutant were also found when ΔtrxAΔtrxC cells were exposed to HOCl (Fig. 3D). This probably results from the fact that impairing both the Trx and Grx systems causes a more severe endogenous oxidative stress in the ΔtrxAΔgshA mutant.

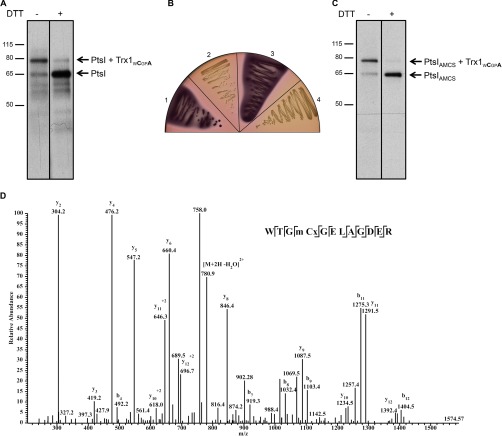

Identification of PtsI as a Novel Redox-regulated Enzyme

To further investigate the interaction between Trx1 and the newly identified proteins, we decided to focus on PtsI. This enzyme was selected because it plays an essential role in the coupled translocation/phosphorylation of several carbohydrates including glucose in bacteria (101, 102) and its activity can be easily monitored in vivo. First, we confirmed that Trx1 (12 kDa) and PtsI (64 kDa) form a mixed-disulfide complex by detecting a DTT-sensitive 76 kDa band in the fraction containing purified Trx1WCGPA bound to its substrates, using a specific anti-PtsI antibody (Fig. 4A). PtsI has four cysteine residues, of which only one (Cys502) is strictly conserved (supplemental Fig. S3). Before dissecting the Trx1-PtsI interaction, we decided to determine the importance of the various cysteine residues for PtsI activity. As shown in Fig. 4B, mutation of Cys502 to serine prevented E. coli to ferment glucose, confirming the importance of this active site residue for activity (103, 104). In contrast, replacement of the three other cysteines, either alone (not shown) or together, had no impact, indicating that they are dispensable for the function of PtsI. Note that all mutant proteins were expressed at physiological levels from the ptsI chromosomal locus. Given the importance of Cys502 for PtsI activity, we postulated that Trx1 might be involved in maintaining this residue reduced in order to keep PtsI active. To test if Trx1 specifically interacts with Cys502, we expressed Trx1WCGPA in a ΔtrxAΔgshA strain producing PtsIAMCS from the ptsI locus (all three nonessential cysteine residues are mutated in PtsIAMCS). As shown in Fig. 4C, we observed the formation of a DTT-sensitive complex between Trx1WCGPA and PtsIAMCS that was recognized by the anti-PtsI antibody. This result implies that Cys502 becomes a Trx1 target following its oxidation, most likely to a sulfenic acid. Because of their high reactivity, sulfenic acids are often difficult to identify. To test if Cys502 of PtsI can be oxidized to a sulfenic acid, PtsIAMCS was incubated with H2O2 and dimedone, a sulfenic acid specific reagent. The protein was then digested with trypsin and the peptide mixture analyzed by LC-MS/MS. As shown in Fig. 4D, the dimedone-modified peptide, corresponding to the sulfenic acid form of PtsIAMCS, could be detected, indicating that Cys502 of PtsI can be oxidized to the sulfenic state. PtsI having three additional cysteines, it is possible that the sulfenic acid rearranges in vivo into an intramolecular disulfide involving one of these residues. Regardless of whether this rearrangement occurs or not, our data indicate that Trx1 recognizes oxidized PtsI, suggesting that it plays a role in protecting PtsI from oxidative inactivation. It is interesting to note that, in the course of PtsI purification, we observed a noncovalent complex between Trx1 and PtsI that remained remarkably stable following successive chromatography steps (not shown), further supporting the functional link between these two proteins.

Fig. 4.

Identification of PtsI as a novel redox-regulated enzyme. A, Trx1WCGPA was expressed in a ΔtrxAΔgshA mutant, purified and concentrated. The elution fraction was then analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-PtsI antibody. The bands corresponding to PtsI alone or in complex with Trx1WCGPA are indicated. Upon DTT addition, the band corresponding to the complex between PtsI and Trx1 disappeared whereas the PtsI band increased, indicating that Trx1WCGPA is released from PtsI under reducing conditions. The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. The fact that PtsI was observed in the nonreduced sample indicates that a portion of this protein co-purified with Trx1WCGPA on the Ni-NTA agarose column. B, Strains expressing different versions of PtsI were streaked on MacConkey plates (containing 0.5% glucose) and glucose fermentation was analyzed. Red colonies indicate glucose fermentation whereas white colonies show no fermentation. Strains are as follows: 1. Wild type, 2. ΔptsI, 3. ptsI::ptsIAMCS, 4. ptsI::ptsIC502S. Cells with a nonfunctional PtsI cannot ferment glucose because of an impaired glucose uptake. C, The complex formed between Trx1WCGPA and PtsIAMCS was analyzed as in A, in a ΔtrxAΔgshA mutant expressing PtsIAMCS from the chromosome (instead of wild-type PtsI). The molecular mass markers (in kDa) are indicated on the left. D, Identification of dimedone on Cys502 of PtsI. The LC-MS/MS spectrum shows data obtained from a +2 parent ion of [M+2H]2+ = 789.9. “m” in the peptide sequence corresponds to a methionine sulfoxide. The Cx residue corresponds to a sulfenic acid modified by dimedone which produces a +138Da mass increment; the y- and b- series of ions allow exact localization of the modified Cys.

CONCLUSIONS

E. coli Trx1 has been identified in 1964 (4). Since then, it has been the focus of intense scrutiny and has become one of the best-characterized members of a large family of oxidoreductases present in all domains of life. However, despite a wealth of information on Trx1, a comprehensive search for proteins depending on Trx1 for reduction had never been carried out. In our study, by expressing a Trx1 mutant with a catalytic site engineered for substrate trapping in cells with altered redox properties, we identified a total of 201 new putative Trx1 targets, considerably expanding the number of intracellular proteins depending on Trx1 for reduction. In addition, we identified proteins that become Trx1 substrates following exposure of the cells to an exogenous oxidative stress as well as proteins that most likely depend on both the Trx and Grx pathways for reduction. Although it is possible that Trx1 reduces disulfide bonds that could form in some of these proteins as a result of a catalytic activity, it is more likely that the majority of the newly identified proteins depend on Trx1 for the reduction of sensitive cysteine residues prone to oxidation by ROS. Determining the identity of the cysteine residues involved in the formation of mixed-disulfide intermediates with Trx1 and identifying the nature of the oxidative modifications affecting the Trx1 substrates will be fields of future research. Furthermore, it will be particularly interesting to elucidate if the oxidation of some of the newly identified Trx1 substrates is part of a regulation mechanism controlling their activity under more oxidizing redox conditions, which could lead to the discovery of new redox-regulated pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pauline Leverrier and Camille Goemans for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful comments, and Asma Boujtat and Gaëtan Herinckx for technical assistance. We also thank Diarmaid Hughes (Uppsala), Thomas Silhavy (Princeton) and Piet A. J. de Boer (Case Western) for providing strains and plasmids, Nassos Typas (EMBL) for providing the anti-MreB antibody and Kenneth Marians (Sloan Kettering) for providing purified MreB. ISA is Aspirant, GL is Chargé de Recherche, and JFC is Maître de Recherche of the F.R.S.-FNRS and an Investigator of the FRFS-WELBIO.

Footnotes

Author contributions: I.S.A. and J.F.C. designed research; I.S.A., D.V., F.B., and G.L. performed research; D.V. and J.F.C. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; I.S.A., G.L., and J.F.C. analyzed data; I.S.A. and J.F.C. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported by the European Research Council (FP7/2007–2013) ERC independent researcher starting grant 282335-Sulfenic, by the WELBIO and by grants from the F.R.S.-FNRS.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- Trx

- Thioredoxin

- A22

- S-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl) isothiourea

- BCP

- Bacterioferritin comigratory protein

- DMD

- Dimedone

- Grx

- Glutaredoxin

- HOCl

- Hypochlorous acid

- H2O2

- Hydrogen peroxide

- IAM

- Iodoacetamide

- IPTG

- Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- LB

- Lysogeny broth

- MalPEG

- Methoxyl polyethylene glycol maleimide

- Msr

- Methionine sulfoxide reductase

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- PAPS reductase

- 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate reductase

- PtsI

- Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase (enzyme I)

- RFP

- Red fluorescent protein

- RNR

- Ribonucleotide reductase

- Tpx

- Thiol peroxidase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collet J. F., and Messens J. (2010) Structure, function, and mechanism of thioredoxin proteins. Antiox. Redox Signal. 13, 1205–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakamura T., Nakamura H., Hoshino T., Ueda S., Wada H., and Yodoi J. (2005) Redox regulation of lung inflammation by thioredoxin. Antiox. Redox Signal. 7, 60–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holmgren A., Soderberg B. O., Eklund H., and Branden C. I. (1975) Three-dimensional structure of Escherichia coli thioredoxin-S2 to 2.8 A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 2305–2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laurent T. C., Moore E. C., and Reichard P. (1964) Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. IV. Isolation and characterization of thioredoxin, the hydrogen donor from Escherichia coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 239, 3436–3444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore E. C., Reichard P., and Thelander L. (1964) Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides.V. Purification and properties of thioredoxin reductase from Escherichia coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 239, 3445–3452 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsang M. L. (1981) Assimilatory sulfate reduction in Escherichia coli: identification of the alternate cofactor for adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulfate reductase as glutaredoxin. J. Bacteriol. 146, 1059–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brot N., Weissbach L., Werth J., and Weissbach H. (1981) Enzymatic reduction of protein-bound methionine sulfoxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 2155–2158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grimaud R., Ezraty B., Mitchell J. K., Lafitte D., Briand C., Derrick P. J., and Barras F. (2001) Repair of oxidized proteins. Identification of a new methionine sulfoxide reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48915–48920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin Z., Johnson L. C., Weissbach H., Brot N., Lively M. O., and Lowther W. T. (2007) Free methionine-(R)-sulfoxide reductase from Escherichia coli reveals a new GAF domain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9597–9602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rietsch A., Belin D., Martin N., and Beckwith J. (1996) An in vivo pathway for disulfide bond isomerization in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13048–13053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rietsch A., Bessette P., Georgiou G., and Beckwith J. (1997) Reduction of the periplasmic disulfide bond isomerase, DsbC, occurs by passage of electrons from cytoplasmic thioredoxin. J. Bacteriol. 179, 6602–6608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baker L. M., and Poole L. B. (2003) Catalytic mechanism of thiol peroxidase from Escherichia coli. Sulfenic acid formation and overoxidation of essential CYS61. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9203–9211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reeves S. A., Parsonage D., Nelson K. J., and Poole L. B. (2011) Kinetic and thermodynamic features reveal that Escherichia coli BCP is an unusually versatile peroxiredoxin. Biochemistry 50, 8970–8981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roos G., and Messens J. (2011) Protein sulfenic acid formation: from cellular damage to redox regulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 314–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nandi D. L., Horowitz P. M., and Westley J. (2000) Rhodanese as a thioredoxin oxidase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 32, 465–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leichert L. I., and Jakob U. (2004) Protein thiol modifications visualized in vivo. PLos Biol. 2, e333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kumar J. K., Tabor S., and Richardson C. C. (2004) Proteomic analysis of thioredoxin-targeted proteins in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3759–3764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hosoya-Matsuda N., Inoue K., and Hisabori T. (2009) Roles of thioredoxins in the obligate anaerobic green sulfur photosynthetic bacterium Chlorobaculum tepidum. Mol. Plant 2, 336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lindahl M., and Florencio F. J. (2003) Thioredoxin-linked processes in cyanobacteria are as numerous as in chloroplasts, but targets are different. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 16107–16112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perez-Perez M. E., Florencio F. J., and Lindahl M. (2006) Selecting thioredoxins for disulphide proteomics: target proteomes of three thioredoxins from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proteomics 6, S186–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mata-Cabana A., Florencio F. J., and Lindahl M. (2007) Membrane proteins from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 interacting with thioredoxin. Proteomics 7, 3953–3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Motohashi K., Kondoh A., Stumpp M. T., and Hisabori T. (2001) Comprehensive survey of proteins targeted by chloroplast thioredoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11224–11229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balmer Y., Koller A., del Val G., Manieri W., Schurmann P., and Buchanan B. B. (2003) Proteomics gives insight into the regulatory function of chloroplast thioredoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 370–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Balmer Y., Vensel W. H., Tanaka C. K., Hurkman W. J., Gelhaye E., Rouhier N., Jacquot J. P., Manieri W., Schurmann P., Droux M., and Buchanan B. B. (2004) Thioredoxin links redox to the regulation of fundamental processes of plant mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2642–2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamazaki D., Motohashi K., Kasama T., Hara Y., and Hisabori T. (2004) Target proteins of the cytosolic thioredoxins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshida K., Noguchi K., Motohashi K., and Hisabori T. (2013) Systematic exploration of thioredoxin target proteins in plant mitochondria. Plant Cell Physiol. 54, 875–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong J. H., Cai N., Balmer Y., Tanaka C. K., Vensel W. H., Hurkman W. J., and Buchanan B. B. (2004) Thioredoxin targets of developing wheat seeds identified by complementary proteomic approaches. Phytochemistry 65, 1629–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lemaire S. D., Guillon B., Le Marechal P., Keryer E., Miginiac-Maslow M., and Decottignies P. (2004) New thioredoxin targets in the unicellular photosynthetic eukaryote Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7475–7480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marchand C., Le Marechal P., Meyer Y., and Decottignies P. (2006) Comparative proteomic approaches for the isolation of proteins interacting with thioredoxin. Proteomics 6, 6528–6537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alkhalfioui F., Renard M., Vensel W. H., Wong J., Tanaka C. K., Hurkman W. J., Buchanan B. B., and Montrichard F. (2007) Thioredoxin-linked proteins are reduced during germination of Medicago truncatula seeds. Plant Physiol. 144, 1559–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balmer Y., Vensel W. H., Cai N., Manieri W., Schurmann P., Hurkman W. J., and Buchanan B. B. (2006) A complete ferredoxin/thioredoxin system regulates fundamental processes in amyloplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2988–2993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hall M., Mata-Cabana A., Akerlund H. E., Florencio F. J., Schroder W. P., Lindahl M., and Kieselbach T. (2010) Thioredoxin targets of the plant chloroplast lumen and their implications for plastid function. Proteomics 10, 987–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marchand C. H., Vanacker H., Collin V., Issakidis-Bourguet E., Marechal P. L., and Decottignies P. (2010) Thioredoxin targets in Arabidopsis roots. Proteomics 10, 2418–2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rey P., Cuine S., Eymery F., Garin J., Court M., Jacquot J. P., Rouhier N., and Broin M. (2005) Analysis of the proteins targeted by CDSP32, a plastidic thioredoxin participating in oxidative stress responses. Plant J. 41, 31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sturm N., Jortzik E., Mailu B. M., Koncarevic S., Deponte M., Forchhammer K., Rahlfs S., and Becker K. (2009) Identification of proteins targeted by the thioredoxin superfamily in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kawazu S., Takemae H., Komaki-Yasuda K., and Kano S. (2010) Target proteins of the cytosolic thioredoxin in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol. Int. 59, 298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schlosser S., Leitsch D., and Duchene M. (2013) Entamoeba histolytica: identification of thioredoxin-targeted proteins and analysis of serine acetyltransferase-1 as a prototype example. Biochem. J. 451, 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu C., Jain M. R., Li Q., Oka S., Li W., Kong A. N., Nagarajan N., Sadoshima J., Simmons W. J., and Li H. (2014) Identification of novel nuclear targets of human thioredoxin 1. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 3507–3518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu J., and Holmgren A. (2014) The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 66, 75–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Casadaban M. J. (1976) Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104, 541–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miller J. H. (1992) A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, ed), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu D., Ellis H. M., Lee E. C., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., and Court D. L. (2000) An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5978–5983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Arts I. S., Ball G., Leverrier P., Garvis S., Nicolaes V., Vertommen D., Ize B., Tamu Dufe V., Messens J., Voulhoux R., and Collet J. F. (2013) Dissecting the machinery that introduces disulfide bonds in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 4, e00912–00913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vizcaino J. A., Deutsch E. W., Wang R., Csordas A., Reisinger F., Rios D., Dianes J. A., Sun Z., Farrah T., Bandeira N., Binz P. A., Xenarios I., Eisenacher M., Mayer G., Gatto L., Campos A., Chalkley R. J., Kraus H. J., Albar J. P., Martinez-Bartolome S., Apweiler R., Omenn G. S., Martens L., Jones A. R., and Hermjakob H. (2014) ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 223–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nurse P., and Marians K. J. (2013) Purification and characterization of Escherichia coli MreB protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 3469–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choi S., Jeong J., Na S., Lee H. S., Kim H. Y., Lee K. J., and Paek E. (2010) New algorithm for the identification of intact disulfide linkages based on fragmentation characteristics in tandem mass spectra. J. Proteome Res. 9, 626–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ritz D., Patel H., Doan B., Zheng M., Aslund F., Storz G., and Beckwith J. (2000) Thioredoxin 2 is involved in the oxidative stress response in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2505–2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Collet J. F., D'Souza J. C., Jakob U., and Bardwell J. C. (2003) Thioredoxin 2, an oxidative stress-induced protein, contains a high affinity zinc binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45325–45332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li K., Hartig E., and Klug G. (2003) Thioredoxin 2 is involved in oxidative stress defence and redox-dependent expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Microbiology 149, 419–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sommer A., and Traut R. R. (1974) Diagonal polyacrylamide-dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis for the identification of ribosomal proteins crosslinked with methyl-4-mercaptobutyrimidate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 3946–3950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Molinari M., and Helenius A. (1999) Glycoproteins form mixed disulphides with oxidoreductases during folding in living cells. Nature 402, 90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Molinari M., and Helenius A. (2000) Chaperone selection during glycoprotein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 288, 331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Anastasiou D., Poulogiannis G., Asara J. M., Boxer M. B., Jiang J. K., Shen M., Bellinger G., Sasaki A. T., Locasale J. W., Auld D. S., Thomas C. J., Vander Heiden M. G., and Cantley L. C. (2011) Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses. Science 334, 1278–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tomich J. M., and Colman R. F. (1985) Reaction of 5′-p-fluorosulfonylbenzoyl-1,N6-ethenoadenosine with histidine and cysteine residues in the active site of rabbit muscle pyruvate kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 827, 344–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ishii T., Sunami O., Nakajima H., Nishio H., Takeuchi T., and Hata F. (1999) Critical role of sulfenic acid formation of thiols in the inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by nitric oxide. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58, 133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shenton D., and Grant C. M. (2003) Protein S-thiolation targets glycolysis and protein synthesis in response to oxidative stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 374, 513–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dimmeler S., Lottspeich F., and Brune B. (1992) Nitric oxide causes ADP-ribosylation and inhibition of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 16771–16774 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hildebrandt T., Knuesting J., Berndt C., Morgan B., and Scheibe R. (2015) Cytosolic thiol switches regulating basic cellular functions: GAPDH as an information hub? Biol. Chem. 396, 523–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Little C., and Holland P. (1972) Sulfhydril groups and the concerted inhibition of NADP + -linked isocitrate dehydrogenase. Can. J. Biochem. 50, 1109–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kil I. S., and Park J. W. (2005) Regulation of mitochondrial NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase activity by glutathionylation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10846–10854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yang E. S., Richter C., Chun J. S., Huh T. L., Kang S. S., and Park J. W. (2002) Inactivation of NADP(+)-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase by nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33, 927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wood D. C., Hodges C. T., Howell S. M., Clary L. G., and Harrison J. H. (1981) The N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive cysteine residue in the pH-dependent subunit interactions of malate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 9895–9900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Eaton P., and Shattock M. J. (2002) Purification of proteins susceptible to oxidation at cysteine residues: identification of malate dehydrogenase as a target for S-glutathiolation. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 973, 529–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lemaire S. D., Quesada A., Merchan F., Corral J. M., Igeno M. I., Keryer E., Issakidis-Bourguet E., Hirasawa M., Knaff D. B., and Miginiac-Maslow M. (2005) NADP-malate dehydrogenase from unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. A first step toward redox regulation? Plant Physiol. 137, 514–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hara S., Motohashi K., Arisaka F., Romano P. G., Hosoya-Matsuda N., Kikuchi N., Fusada N., and Hisabori T. (2006) Thioredoxin-h1 reduces and reactivates the oxidized cytosolic malate dehydrogenase dimer in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32065–32071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Raibaud O., and Goldberg M. E. (1977) The reactivity of one essential cysteine as a conformational probe in Escherichia coli tryptophanase. Application to the study of the structural influence of subunit interactions. Eur. J. Biochem. 73, 591–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nihira T., Yasuda T., Kakizono T., Taguchi H., Ichikawa M., Toraya T., and Fukui S. (1985) Functional role of cysteinyl residues in tryptophanase. Eur. J. Biochem. 149, 129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]