Abstract

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) act either through membrane lysis or by attacking intracellular targets. Intracellular targeting AMPs are a resource for antimicrobial agent development. Several AMPs have been identified as intracellular targeting peptides; however, the intracellular targets of many of these peptides remain unknown. In the present study, we used an Escherichia coli proteome microarray to systematically identify the protein targets of three intracellular targeting AMPs: bactenecin 7 (Bac7), a hybrid of pleurocidin and dermaseptin (P-Der), and proline-arginine-rich peptide (PR-39). In addition, we also included the data of lactoferricin B (LfcinB) from our previous study for a more comprehensive analysis. We analyzed the unique protein hits of each AMP in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. The results indicated that Bac7 targets purine metabolism and histidine kinase, LfcinB attacks the transcription-related activities and several cellular carbohydrate biosynthetic processes, P-Der affects several catabolic processes of small molecules, and PR-39 preferentially recognizes proteins involved in RNA- and folate-metabolism-related cellular processes. Moreover, both Bac7 and LfcinB target purine metabolism, whereas LfcinB and PR-39 target lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. This suggested that LfcinB and Bac7 as well as LfcinB and PR-39 have a synergistic effect on antimicrobial activity, which was validated through antimicrobial assays. Furthermore, common hits of all four AMPs indicated that all of them target arginine decarboxylase, which is a crucial enzyme for Escherichia coli survival in extremely acidic environments. Thus, these AMPs may display greater inhibition to bacterial growth in extremely acidic environments. We have also confirmed this finding in bacterial growth inhibition assays. In conclusion, this comprehensive identification and systematic analysis of intracellular targeting AMPs reveals crucial insights into the intracellular mechanisms of the action of AMPs.

Natural antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)1 are an evolutionarily conserved defense system of organisms against invading microorganisms. AMPs are effective against a wide range of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, parasites, and some viruses (1). In general, AMPs are cationic peptides with fewer than 50 amino acid residues. To date, two main mechanisms of action have been identified for AMPs acting as antimicrobial agents (2): (1) membrane integrity disruption and (2) intracellular activity inhibition. Although the basic properties of all AMPs are similar, each AMP has a unique structure and microbial intracellular activity inhibition mechanism. For example, indolicidin inhibits DNA synthesis (3), whereas buforin II binds to DNA and RNA (4), mersacidin (a lantibiotic) binds to Lipid II and blocks peptidoglycan metabolism (5), tachyplesin I binds to the minor groove of DNA duplexes (6), microcin B17 inhibits DNA gyrase (thus influencing DNA replication) (7, 8), microcin J25 recognizes the secondary channel of RNA polymerase (inhibiting transcription) (9), and pyrrhocoricin inhibits the biological function of the heat shock protein, DnaK (10). However, because no systematic study has been reported, the intracellular targets of numerous AMPs, such as bactenecin 7 (Bac7), hybrid of pleurocidin and dermaseptin (P-Der), and proline-arginine-rich peptide (PR-39), remain unclear (11–13). The N-terminal fragment of Bac7 (1–35) inhibits bacterial growth through a nonlytic mechanism at low concentrations (11), and P-Der inhibits macromolecular synthesis in bacteria at the lowest inhibition concentration (13). PR-39 inhibits protein and DNA synthesis without cell membrane lysis (12). These reports suggest that Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39 have intracellular activities against microorganisms. However, the exact mechanism of action and the intracellular targets remain unclear. Thus, we used an Escherichia coli proteome microarray to systematically identify the protein targets. The E. coli proteome microarray contained the entire proteome of E. coli K12 and provided a high-throughput rapid platform for protein interactome identification (14). The E. coli proteome microarray has been used in many studies such as research on protein-DNA (14) and protein-peptide interaction (15, 16) and biomarker identification (17). We previously applied the E. coli proteome microarray as a high-throughput platform to identify the intracellular targets of lactoferricin B (LfcinB). Our results indicated that LfcinB reduces the ability of E. coli to respond to irregular environments by inhibiting the phosphorylation of two response regulators (basR and creB) and by influencing the metabolic process through multiple protein targets (15, 16).

In the present study, we identified the protein targets of Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39 and also included the LfcinB data to systematically elucidate the association between AMPs and their specific or common target proteins. Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs), Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Pfam analysis were used to characterize the unique and common target proteins of all four AMPs. KEGG and GO analysis revealed that LfcinB had synergistic effects in combination with Bac7 or PR-39 and that all four AMPs targeted arginine decarboxylase. We further validated these findings through antibacterial assays.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fabrication of E. coli K12 Proteome Chips

The detailed protocol was described in our previous study (14). Briefly, each E. coli K12 ASKA library clone (18) was incubated in LB medium containing 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37 °C. The overnight cultures were diluted in fresh LB medium and further grown until the optical density at 595 nm (OD595) reached ∼0.8. Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside was then added to induce protein expression by further incubation for 2 h. After induction, cell pellets were collected through centrifugation at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C before protein purification. For purification, the cell pellets were resuspended in a lysis buffer containing benzonase, CelLytic B, imidazole, lysozyme, proteinase inhibitor mixture, and Ni-NTA superflow resins. Subsequently, the resuspended cultures were transferred into 96-well filter plates and then washed with wash buffer I (50 mm NaH2PO4, 300 mm NaCl, 20% glycerol, 20 mm imidazole, and 0.1% Tween 20) and wash buffer II (50 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, 30% glycerol, 30 mm imidazole, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 8). Finally, the proteins were eluted using an elution buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, 30% glycerol, 300 mm imidazole, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.5). To fabricate the chips, the purified proteins were transferred to 384-well plates and individual proteins were printed (in duplicate) on aldehyde slides at 4 °C by using a high throughput microarray spotter with 48 pins (SmartArrayerTM 136, Capitalbio Corporation, Beijing, China).

E. coli K12 proteome chip assay for Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39

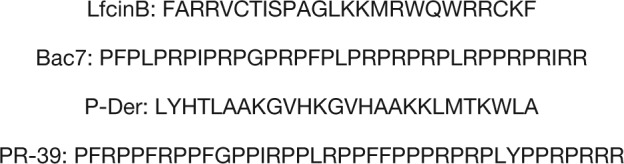

The chips were first blocked using 1% BSA and then probed with N-terminal-biotinylated Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39 in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBS-T; 0.05% Tween 20) with 1% BSA individually in a hybridization chamber with shaking at room temperature for 1 h. After washing, the chips were probed with DyLightTM 549-labeled anti-His antibody (Abcam®, Cambridge, UK) and DyLightTM 649-labeled streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, the chips were washed three times with TBS-T. After the final wash with distilled water, the chips were dried through brief centrifugation and then scanned using a microarray scanner (LuxScan 10K, CapitalBio). The following amino acid sequences of Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39 were used:

|

For Bac7, only the 1–35-amino acid residue fragment was used because its antibacterial and intracellular activities are similar to those of intact Bac7 (11).

Bioinformatics Analysis of the Chip Assay Results

GenePix Pro 6.0 was used to align each protein spot and export all chip assay image results as text files. ProCAT (19) was applied to normalize the signals of the four AMPs and the anti-His antibody. Subsequently, the relative binding ability of each AMP to each protein was estimated using the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of each AMP to that of the anti-His antibody. The signals were considered positive only when they fulfilled the following cutoffs: (1) the local cutoff, defined as two standard deviations above the signal mean for each spot, and (2) the fold change of each AMP signal to anti-His antibody is at least 0.5. For each AMP, three chips were used to conduct triplicate assays and each protein was printed duplicately in one chip. The protein was determined as a hit only if all the 6 spots on 3 chips were defined as positive signals. All bioinformatics analyses were performed using Perl 5.0. COGs (20), GO (21), KEGG (22), and Pfam (23) were used to analyze the protein hits. To determine significant enrichment, for the statistical analysis, Fisher's exact test was performed using the free software R. GO analysis was performed on BiNGO 2.44.

Synergistic Antibacterial Assay

E. coli MG1655 was grown for 8–9 h in LB medium and then diluted 500-fold by using fresh LB medium (∼1.0 × 106 cells/ml). Culture growth was observed with or without AMPs in NuncTM F 96-well plates by using fresh LB medium as a blank. The working concentrations of LfcinB, PR-39, and Bac7 were 40, 25, and 100 μg/ml respectively. A 96-well plate was incubated at 37 °C in an automated Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) with OD600 readings obtained at 20-min intervals for 7 h (shaking for 15 s before each reading). Data were collected automatically by using Gen5TM reader control and data analysis software (BioTek Instruments). We calculated the expected value at a given interval (EXY) as follows (24):

Here OD0 is the OD of E. coli MG1655 in the absence of AMPs and ODX and ODY are the ODs of E. coli MG1655 in the presence of LfcinB and PR-39 or Bac7 at that interval, respectively.

Acid Shock Antibacterial Assay

We performed this assay as described previously (25, 26). E. coli MG1655 was cultured overnight at 37 °C in M9 minimal medium (6 g/L of Na2HPO4, 4 g/L of glucose, 3 g/L of KH2PO4, 1 g/L of NH4Cl, 0.5 g/L of NaCl, 0.25 g/L of MgSO47H2O, 15 mg/L of CaCl22H2O, and 1 mg/L of thiamine-HCl). To test the cell survival rate after acid shock and various AMP treatments, overnight E. coli cultures were diluted 100-fold by using EG medium (73 mm K2HPO4, 17 mm NaNH4HPO4, 0.8 mm MgSO4, 10 mm citrate, 15 mm arginine, and 0.4% glucose, and then adjusted to pH 2.5); in addition, the AMPs (Bac7, LfcinB, P-Der, and PR-39) as well as the negative control cecropin P1 were individually added. After 1-h incubation at 37 °C, the cells were plated on LB agar and incubated overnight and then subjected to colony counting.

RESULTS

E. coli Proteome Microarray Assay

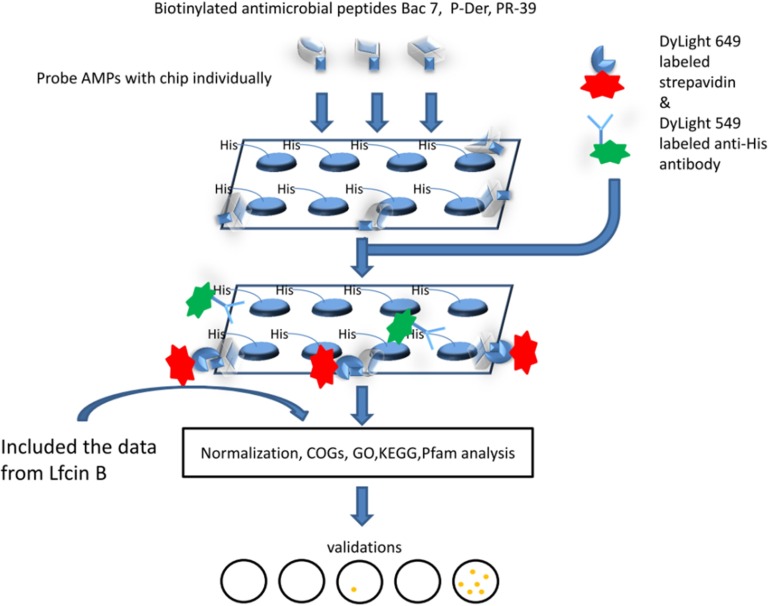

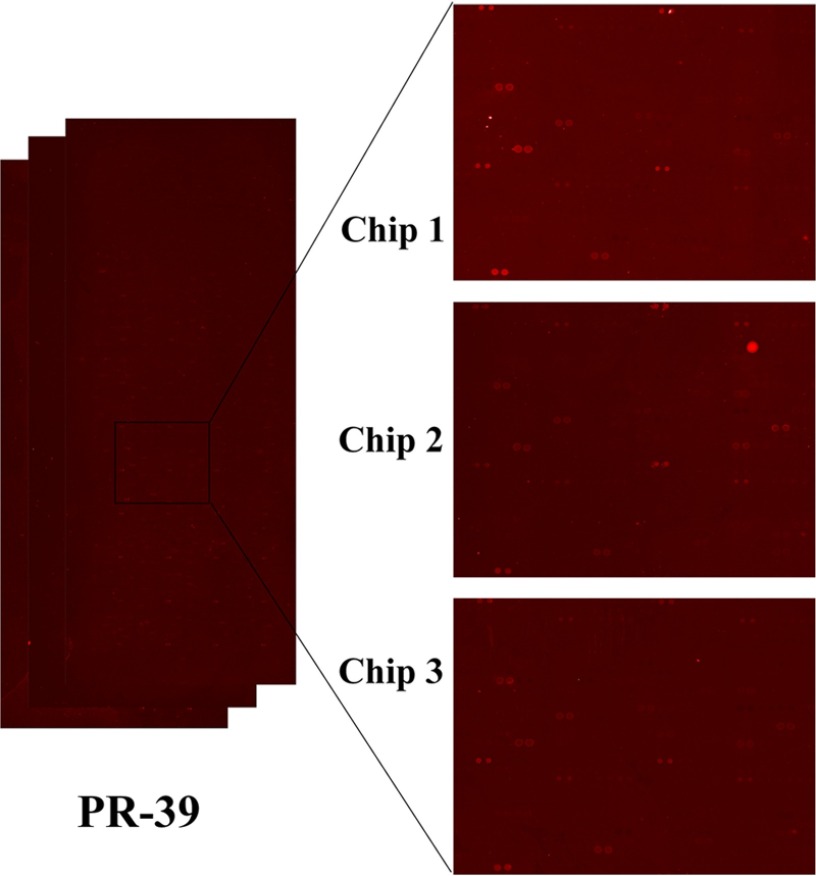

To elucidate the association between each AMP and their specific or common target proteins, the E. coli proteome microarray was applied to provide a global profile of each AMP. The overall schematic of this study is depicted in Fig. 1. The chips were used to probe the biotinylated AMPs individually and then to probe the DyLightTM 649-labeled streptavidin and DyLightTM 549-labeled anti-His antibody. Because all proteins on the chips have His tags, the signal of DyLightTM 549-labeled anti-His antibody represents the relative protein amount. We applied ProCAT for data normalization and positive hit selection (19); because the proteins were printed randomly on the chips, the signal distribution was adjusted to fit a normal distribution. Spot signals were identified as positive if their signals were larger than the local cutoff, which was mean plus two standard deviations. In addition, the signal fold change of AMP to anti-His antibody should be at least 0.5. For each AMP, three chips were used to conduct triplicate assays and each protein was printed duplicately in one chip. The protein was determined as a hit only if all the six spots on three chips were defined as positive signals. By analyzing these protein hits, we elucidated the unique and common target proteins of the four AMPs. Under identical experimental procedures, each AMP displayed a unique image pattern. This phenomenon may be because of individual characteristics of the four AMPs such as charge and hydrophobicity. To show the reproducibility of the chip assays, the triplicate enlarged chip images of PR-39 (as an example) are shown in Fig. 2. Moreover, to show the reproducibility of duplicates within a chip, we also used PR-39 as an example to plot a correlation figure (supplemental Fig. S1). After data normalization and positive hit selection, the protein targets for each AMP were generated and ranked according to their relative binding affinity, defined as the signal of the AMP divided by the signal from the anti-His antibody. The total number of protein hits for Bac7, LfcinB, P-Der, and PR-39 were 323, 303, 252, and 434, respectively. The protein hit list is displayed in supplementary Information.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of this study. The E. coli proteome microarray chips were individually probed with three biotinylated AMPs (Bac7, P-Der and PR-39) to identify their binding proteins. DyLightTM 649-labeled streptavidin was used to indicate binding between the AMPs and proteins. For normalization, DyLightTM 549-labeled anti-His tag antibody was used to detect the relative protein amount on the chips. We included LfcinB-binding proteins identified in our previous study in addition to those of the three new AMPs, and systematically analyzed the targets of all four AMPs.

Fig. 2.

Representative chip images. Triplicate enlarges chip images of PR-39 to show the reproducibility of the chip assays.

COG Analysis for Individual Hits of Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39

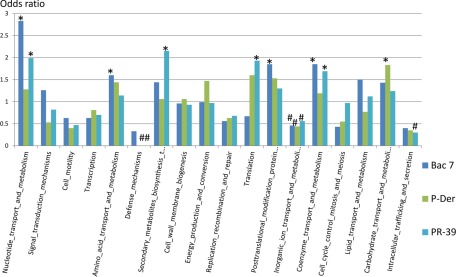

To provide a phylogenetic classification of the protein hits of the four AMPs, COG analysis was performed. The results of COG analysis in Fig. 3 indicate the function enrichment of the AMP protein hits. Bac7 showed enrichment in the nucleotide transport and metabolism, amino acid transport and metabolism, post-translational modification protein turnover chaperones, and coenzyme transport and metabolism. Renato et al. (27) reported that Bac7 binds to bacterial proteins and inhibits protein synthesis. Therefore, we anticipated enrichment in ribosomal proteins. Although this was not observed in Bac7, we observed 11 ribosomal proteins in the Bac7-binding protein list (supplementary Information). Renato et al. (28) also showed that Bac7 binds to the heat shock protein DnaK. Although DnaK was not in the protein list because of our strict cutoff, we also observed that Bac7 can bind to DnaK.

Fig. 3.

COG analysis of the protein hits of Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39. COG analysis was initially applied to provide a phylogenetic classification of proteins identified by each AMP and consequently classify the protein targets of Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39. * significant enrichment in the corresponding category; # significant underrepresentation.

In addition to Bac7, P-Der showed enrichment in carbohydrate transport and metabolism, whereas PR-39 showed enrichment in nucleotide transport and metabolism, secondary metabolites biosynthesis transport and catabolism, translation, and coenzyme transport and metabolism (Fig. 3). The category inorganic ion transport and metabolism was underrepresented for Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39, indicating that these intracellular targeting AMPs may have low preference toward recognizing proteins in this category.

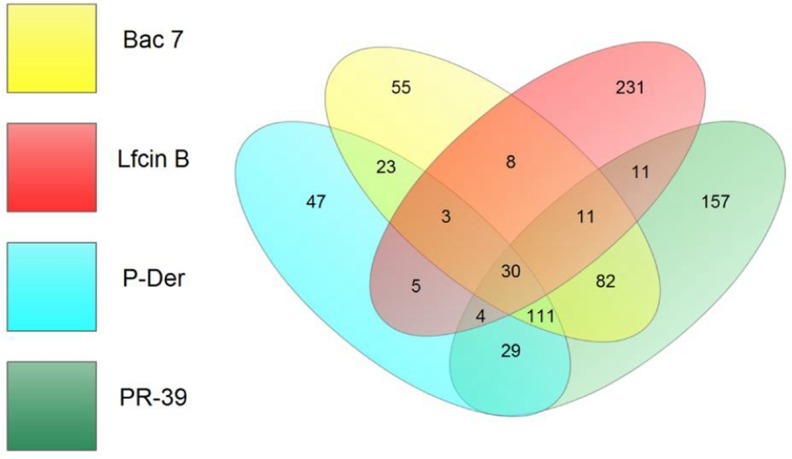

GO Analysis of the Unique Hits of Each AMP

Different AMPs have different antimicrobial mechanisms, possibly because of their unique protein targets. Thus, in addition to the COG analysis, we also used other bioinformatics tools (GO and KEGG) to analyze the unique protein targets of each AMP (i.e. the protein hits shared by more than one AMP were not included in this analysis). The Venn diagram in Fig. 4 shows the protein hit number distribution of all four AMPs. The four ellipses show the total number of hits for the four AMPs (Bac7, yellow; LfcinB, red; P-Der, cyan; and PR-39, green). The nonoverlapping parts of the four ellipses represent the unique protein hits for each AMP (Bac7, 55; LfcinB, 231; P-Der, 47; and PR-39, 157). To analyze the unique protein targets of each AMP, we used GO analysis and characterized the unique hits for each AMP (Table I). For Bac7, enrichment was observed in nucleobase, nucleoside, and nucleotide interconversion and kinase activity. DNA synthesis is crucial for cell survival; in addition, kinase performs essential signal transduction functions. For LfcinB, enrichments were observed in transcriptional activator activity and biosynthetic processes of many carbohydrates (both p < 0.01) including lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS biosynthesis is particularly crucial because LPS is the major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Several studies have designed specific compounds against LPS biosynthesis (29, 30). Here, we observed that LfcinB might interrupt LPS biosynthesis through intracellular inhibitory activity (rfaG, rfaI, wcaC, yibB, yfbF, wcaL, yefE, rfaZ, rfaY, yefG, htrB, rfaQ, and rfaS). For P-Der, half of the GO analysis results were associated with the catabolic processes, including those of small molecules (e.g. pentose and l-arabinose catabolism), suggesting that the major antibacterial mechanism of P-Der is the inhibition of the bacterial catabolic processes. For PR-39, half of the GO analysis results were associated with RNA (RNA binding, ribonucleoprotein complex and ribosome biogenesis, RNA metabolic process, RNA modification, and ncRNA processing). Thus, PR-39 attacks proteins involved in RNA-related processes; therefore, this AMP may interrupt several cellular RNA processes.

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram for the number of protein hits from GO analysis among the four AMPs. The number of unique hits of Bac7, LfcinB, P-Der, and PR-39 were 55, 231, 47, and 157 respectively. Bac7 and PR-39 showed 82 common hits (Bac7 and PR-39 belong to the same family, cathelicidin). All four AMPs shared 30 hits.

Table I. GO analysis of the unique hits of each AMP.

| Description | p value | Hit in this Category | Total gene in this category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bac 7 | |||

| Nucleobase, nucleoside and nucleotide interconversion | 0.0221 | 4 | 19 |

| Kinase activity | 0.0405 | 9 | 177 |

| Lfcin B | |||

| Transcription activator activity | 0.0011 | 16 | 94 |

| Carbohydrate biosynthetic process | 0.0013 | 23 | 181 |

| Polysaccharide biosynthetic process | 0.0020 | 21 | 162 |

| Cellular polysaccharide biosynthetic process | 0.0032 | 16 | 109 |

| Cellular carbohydrate biosynthetic process | 0.0061 | 17 | 128 |

| Lipopolysaccharide biosynthetic process | 0.0095 | 13 | 86 |

| Sequence-specific DNA binding | 0.01 | 12 | 76 |

| Transcription repressor activity | 0.017 | 14 | 104 |

| Pigment metabolic process | 0.024 | 5 | 16 |

| Purine base biosynthetic process | 0.03 | 3 | 5 |

| Transferase activity, transferring glycosyl groups | 0.03 | 10 | 65 |

| P-Der | |||

| Wide pore channel activity and porin activity | 0.027 | 4 | 27 |

| Pentose catabolic process | 0.034 | 3 | 13 |

| L-arabinose catabolic process | 0.034 | 2 | 4 |

| Small molecule catabolic process | 0.034 | 8 | 189 |

| Pore complex | 0.034 | 3 | 17 |

| Isomerase activity | 0.047 | 6 | 113 |

| PR-39 | |||

| RNA binding | 0.0052 | 16 | 145 |

| Cytosol | 0.0183 | 15 | 148 |

| Ribonucleoprotein complex and ribsome biogenesis | 0.0183 | 8 | 47 |

| RNA metabolic process | 0.0183 | 16 | 171 |

| RNA modification | 0.0261 | 9 | 66 |

| ncRNA processing | 0.0285 | 10 | 85 |

| One-carbon metabolic process | 0.0322 | 7 | 45 |

| Tetrahydrofolate metabolic and biosynthetic process | 0.0322 | 3 | 6 |

| Dihydrofolate reductase activity | 0.0498 | 2 | 2 |

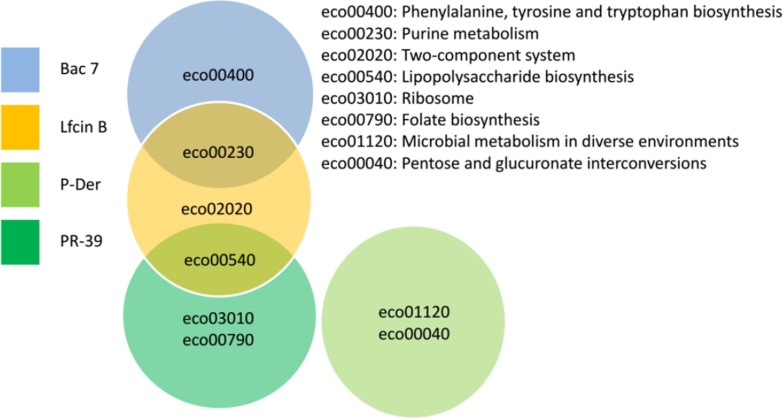

KEGG Analysis of the Unique Hits of the Four AMPs

In addition to the GO analysis, we also used KEGG to analyze the unique protein hits of each AMP. Fig. 5 shows a Venn diagram depicting the KEGG analysis results, and Table II provides detailed information regarding the KEGG analysis. Most results were consistent with those of the GO analysis; for example, the result for the purine metabolism for Bac7 is consistent with the GO result (nucleobase, nucleoside, and nucleotide interconversion). For LfcinB, the only unique category two-component system was associated with the transcription-related categories of the GO analysis results. For P-Der, the pentose metabolism was observed in both GO and KEGG analyses. PR-39 also had enrichment in the RNA-related processes in both analyses. Particularly, PR-39 targeted the folate biosynthesis pathway by inhibiting three proteins (folA, folE, and folM); folate is essential for amino acid synthesis. In addition, this pathway does not exist in mammals; thus, the folate biosynthesis pathway has been considered a potential target during antibacterial compound development (31, 32). In particular, folA is responsible for the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate, which is crucial for protein and nucleic acid biosynthesis; folA is a well-studied target for the antibiotics trimethoprim and pyrimethamine (33–36).

Fig. 5.

Venn diagram for the enriched pathways among the four AMPs (KEGG analysis). This figure displays the enriched pathways for each AMP. This analysis was used to analyze the unique hits of the four AMPs. The result showed that LfcinB still had the enriched pathways identical to those of Bac7 and PR-39 through different protein hits.

Table II. KEGG analysis of the unique hits of each AMP.

| Hits defined in this category | Hits in this category | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bac 7 | |||

| Purine metabolism | 87 | 5 | 0.043 |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 21 | 3 | 0.013 |

| Lfcin B | |||

| Purine metabolism | 87 | 9 | 0.014 |

| Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis | 27 | 5 | 0.008 |

| Two-component system | 130 | 11 | 0.04 |

| P-Der | |||

| Microbial metabolism in diverse environments | 208 | 6 | 0.044 |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 27 | 3 | 0.005 |

| PR-39 | |||

| Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis | 27 | 4 | 0.02 |

| Ribosome | 79 | 7 | 0.03 |

| Folate biosynthesis | 12 | 3 | 0.013 |

In addition to specific pathways attacked by each AMP, Fig. 5 shows that some AMPs have common enrichment processes in the same pathway among the unique hits, such as purine metabolism (shared by Bac7 and LfcinB) and LPS biosynthesis (shared by LfcinB and PR-39). Because purine is required for nucleic acid synthesis, it is an effective target for antimicrobial drugs. According to our results, Bac7 had five hits (purL, xapA, allA, gpp, and gmk) and LfcinB had nine hits (nrdD, purT, ybcF, holC, purF, add, holB, yfbR, and purC); in addition, the total number of proteins in this pathway is 87, suggesting that the combination of Bac7 and LfcinB has a synergistic effect. For LPS biosynthesis, LfcinB had five hits (waaY, rfaQ, waaI, wag, and lpxL), and PR-39 had four hits (lpxC, lpxD, lpxM, and kdsB); in addition, the total number of proteins in this pathway is 27 (i.e. one-third of the proteins in this pathway were targeted by LfcinB and PR-39). Thus, the combination of LfcinB and PR-39 may have a synergistic effect. For instance, LfcinB targets some proteins in LPS biosynthesis; however, this pathway may have redundant proteins to provide an alternative route to compensate for the LfcinB attack. Furthermore, PR-39 has several other targets in LPS biosynthesis; both the main and alternative LPS biosynthesis pathways would likely be targeted by the combinations, thus inhibiting bacterial growth synergistically. Next, we validated both synergistic effects through antibacterial assays.

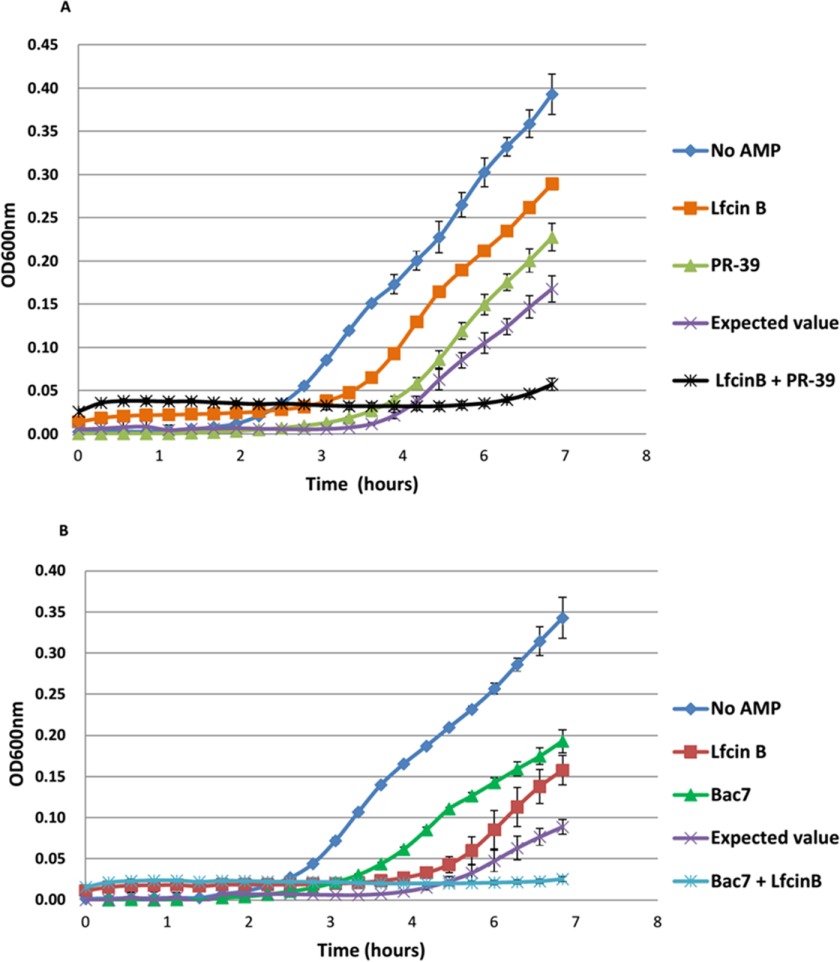

Validation of Synergistic Effects of Bac7 and LfcinB as well as LfcinB and PR-39 on E. coli Growth Inhibition

To experimentally determine the presence of synergistic effect between Bac7 and LfcinB as well as LfcinB and PR-39 on E. coli survival, we analyzed individual AMPs along with their combinations through E. coli growth curves (Fig. 6). The growth curves clearly show that LfcinB and PR-39 individually had a smaller inhibition effect than did their combination (Fig. 6A). The anticipated OD of the LfcinB and PR-39 combination was calculated according to the inhibitory effect of the individual LfcinB and PR-39 in sequence (i.e. the OD of E. coli without AMPs multiplied the percentage of the remaining bacteria after LfcinB treatment and multiplied again the percentage of the remaining bacteria after PR-39 treatment). The results were compared with the experimental data of the LfcinB and PR-39 combination. The comparison revealed that the LfcinB and PR-39 combination showed a significantly larger inhibitory effect than anticipated, indicating a synergistic effect between LfcinB and PR-39, which was also observed for the Bac7 and LfcinB combination (Fig. 6B). These results validated the synergy prediction of our proteome microarray analysis.

Fig. 6.

Growth inhibition of individual and combined AMPs. Inhibition of cell growth was observed in the presence of individual and combined AMPs. The results show that the inhibition of AMP combinations was higher than that expected through calculating the individual inhibitions in sequence. A, Individual and combined effects of LfcinB and PR-39. B, Individual and combined effects of LfcinB and Bac7. These results show the synergistic effects of the AMP combinations.

Protein Domain Analysis of the Unique Hits of Each AMP

In addition to the GO and KEGG analyses, Pfam analysis was performed because it provides enrichment information on domain and protein families (23). Table III displays the Pfam analysis results for the unique hits of each AMP. The Pfam analysis indicated that Bac7 has only one enriched category: the phospho-acceptor domain of histidine kinases. This result accords with the GO analysis results, which also showed enriched kinase activity. For LfcinB, significant enrichment was observed in 10 categories: BPD_transp_2, Acyltransferase, Glycos_transf_1, TetR_N, HTH_1, HTH_18, HemY_N, LysR_substrate, CSS_motif, and EAL. P-Der had only one enriched protein domain in NiFeSe_Hases. PR-39 showed enrichment in nine protein families: 4HBT, SpoU_methylase, HypA, GFO_IDH_MocA_C, adh_short, GFO_IDH_MocA, Abhydrolase_6, zf-B_box, and SEC_C. These results indicate that each AMP has a unique preference to recognize the proteins that belong to different domain families.

Table III. Pfam analysis results of the unique hits of each AMP.

| Total_En | Chip_En | p value | Odd ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bac 7 | ||||

| HisKA | 21 | 2 | 0.038 | 7.091 |

| Lfcin B | ||||

| BPD_transp_2 | 13 | 3 | 0.043 | 4.4 |

| Acyltransferase | 4 | 2 | 0.033 | 9.53 |

| Glycos_transf_1 | 8 | 3 | 0.015 | 7.15 |

| TetR_N | 13 | 3 | 0.043 | 4.4 |

| HTH_1 | 46 | 6 | 0.045 | 2.5 |

| HTH_18 | 27 | 6 | 0.006 | 4.239 |

| HemY_N | 2 | 2 | 0.014 | 19.032 |

| LysR_substrate | 45 | 6 | 0.042 | 2.544 |

| CSS_motif | 5 | 2 | 0.044 | 7.626 |

| EAL | 17 | 4 | 0.019 | 4.488 |

| P-Der | ||||

| NiFeSe_Hases | 4 | 2 | 0.0017 | 46.47 |

| PR-39 | ||||

| 4HBT | 7 | 2 | 0.04 | 7.61 |

| SpoU_methylase | 5 | 3 | 0.0024 | 15.96 |

| HypA | 4 | 2 | 0.018 | 13.31 |

| GFO_IDH_MocA_C | 5 | 2 | 0.025 | 10.65 |

| adh_short | 19 | 3 | 0.045 | 4.21 |

| GFO_IDH_MocA | 7 | 2 | 0.04 | 7.61 |

| Abhydrolase_6 | 5 | 2 | 0.025 | 10.65 |

| zf-B_box | 3 | 2 | 0.012 | 17.74 |

| SEC_C | 4 | 3 | 0.0015 | 19.95 |

Bioinformatics Analysis of Hits Overlapping Only Between Bac7 and PR-39

Among the four AMPs, Bac7 and PR-39 belong to the same family, cathelicidin, which contains various AMPs that are derived from neutrophil granules. Cathelicidin family peptides contain a conserved cathelin domain and a variable cationic peptide domain. AMPs from this family play crucial roles in the innate immune defense of mammals (37). Furthermore, Bac7 and PR-39 are rich in proline and arginine. Because these two AMPs are similar, investigation of the overlapping hits only between these two AMPs could provide insights regarding their role in antimicrobial function. As shown in Fig. 4, 82 proteins are shared by Bac7 (yellow) and PR-39 (green). Table IV shows the bioinformatics analysis results of these shared hits including those from the GO, KEGG, and Pfam analyses. In the GO analysis, enrichment was observed in the aspartate family amino acid catabolic and metabolic processes. Although this process is essential in microorganisms, it is absent in mammals. Thus, this could possibly aid in the development of antibiotics targeting the proteins of the aspartate family amino acid metabolic processes (38, 39). The KEGG analysis indicated that the overlapping protein hits of Bac7 and PR-39 were overrepresented in fructose and mannose metabolism and in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis. Domain analysis indicated that the hits belonging to Bac7 and PR-39 exhibited significant (p = 0.002) enrichment in three categories (NIF3, Peptidase_C26, and MtlR) suggesting that these two cathelicidin-derived AMPs preferably recognize proteins within those three domains.

Table IV. GO, KEGG, and Pfam analysis results of the hits shared only between Bac7 and PR-39. Bac7 and PR-39 belong to the same family, cathelicidin, and are proline- and arginine-rich peptides.

| p value | Hit in this category | Total gene in this category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO category | |||

| Aspartate family amino acid catabolic process | 0.0217 | 3 | 6 |

| Aspartate family amino acid metabolic process | 0.0217 | 6 | 46 |

| KEGG category | |||

| Eco00051 (Fructose and mannose metabolism) | 0.01604 | 4 | 39 |

| Eco00900 (Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis) | 0.04272 | 2 | 13 |

| Pfam category | |||

| Epimerase | 0.02359 | 2 | 11 |

| NIF3 | 0.00203 | 2 | 2 |

| PEP-utilizers | 0.01145 | 2 | 7 |

| Peptidase_C26 | 0.00203 | 2 | 2 |

| M20_dimer | 0.01413 | 2 | 8 |

| Peptidase_M20 | 0.01413 | 2 | 8 |

| MtlR | 0.00203 | 2 | 2 |

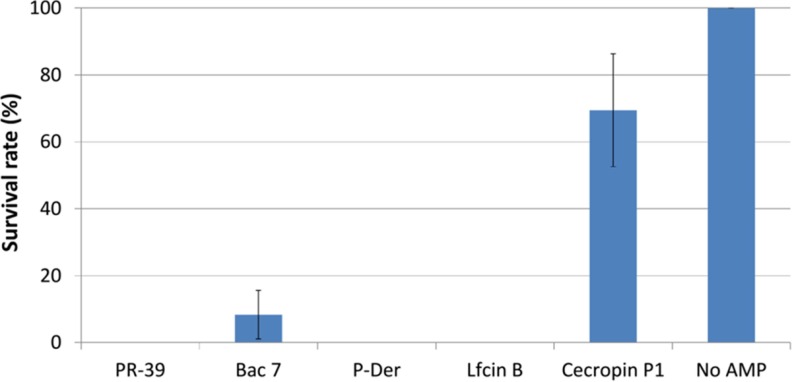

Bioinformatics Analysis of Common Hits Shared by the Four AMPs

Although AMPs vary in structure, they possess common characteristics such as their short length and positive charge. Our four AMPs also displayed intracellular activity (11–13, 40). Analysis of the common hits among these AMPs can provide information regarding the general intracellular mechanisms of AMPs. Table V presents the results of the GO and KEGG analyses, which indicated that the hits shared by the four AMPs showed significant enrichment (p < 0.01) in ornithine metabolism and arginine decarboxylase activity (GO) as well as in arginine and proline metabolism (KEGG). Both the GO and KEGG analyses indicated that all four AMPs have enrichment in the arginine metabolism-related pathways or functions. supplemental Fig. S2 shows the pathway of arginine and proline metabolism (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). The three protein hits (argH, adiA, and sepA) from the KEGG analysis are mapped in this figure. Among these, adiA and sepA are of arginine decarboxylases and are responsible for the decarboxylation of arginine to agmatine; this is an acid resistance system in E. coli, which depends on arginine. Arginine decarboxylase consumes protons and neutralizes environmental pH by removing acidic carboxyl groups (25). Acid resistance is crucial for pathogens because they must survive in the human stomach for up to several hours and overcome the extremely acidic environment (pH < 3) (25, 41, 42). Hence, we validated the effect of all four AMPs on E. coli in an extremely acidic environment.

Table V. GO and KEGG analysis results of the hits shared by all four AMPs.

| p value | Hit in this category | Total gene in this category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO category | |||

| Ornithine metabolic process | 0.00775 | 2 | 2 |

| Arginine decarboxylase activity | 0.00775 | 2 | 2 |

| KEGG category | |||

| Eco00330 (Arginine and proline metabolism) | 0.005492 | 3 | 43 |

Bac7, LfcinB, P-Der, and PR-39 Considerably Affect E. coli Survival in an Extremely Acidic Environment

To confirm whether the four AMPs affect E. coli survival in acidic environments by attacking arginine decarboxylase (adiA and speA), we conducted an antibacterial experiment (25, 43). We used the bacterial count of the plate without AMP treatment as 100% survival to compare the effect of the AMPs on the bacterial survival. Cecropin P1 was used as the negative control because its antibacterial activity is through membrane permeabilization and not through intracellular activity (44). In an extremely acidic environment (EG medium, pH 2.5) containing 1.5 mm arginine, all four intracellular targeting AMPs showed strong inhibition compared with cecropin P1 (Fig. 7; p = 0.02), thus confirming that the four AMPs inhibited the normal function of arginine decarboxylase, leading to growth defects in the case of arginine-dependent acid resistance.

Fig. 7.

Effect of AMPs on E. coli survival in an extremely acidic environment. Here, we confirmed whether the AMPs influence the function of arginine decarboxylase (i.e. converting arginine to agmatine). This conversion is crucial for E. coli to survive in extremely acidic conditions because the conversion consumes the protons, thus increasing the surrounding pH. The results show that Bac7, LfcinB, P-Der, and PR-39 considerably reduce the survival of E. coli in extremely acidic environments, whereas the control peptide cecropin P1 does not.

DISCUSSION

Antibiotic resistance has become a severe problem in clinical practice. Recently, the number of reports of antibiotic-resistant strains, such as those of Tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, has increased; hence, new antimicrobial agents and strategies are urgently required. AMPs can be promising antibacterial agents because several of them inhibit antibiotic-resistant microorganisms (45). Thus, AMPs can be novel resources for antimicrobial agent and strategy development.

Intracellular targeting AMPs have more complex mechanisms of action for microbial growth inhibition than do membrane-active AMPs. For instance, the four AMPs in this study showed specific targets as well as some common targets. Thus, intracellular targeting AMPs become a favorable resource for developing novel strategies against microorganisms. Furthermore, owing to the complexity of their antimicrobial mechanisms, developing resistance to AMPs is difficult for microorganisms. This perspective was also reported by Renato et al. (28), who demonstrated that Bac7 binds to DnaK and that DnaK-deficient E. coli strains do not differ significantly from the wild-type strain; they concluded that Bac7 has multiple targets, which increases the difficulty of resistance development for bacterial strains.

As mentioned before, for many intracellular targeting AMPs, only a few targets have been identified. In our previous studies, we have shown that proteome microarrays are useful for identifying the intracellular protein targets of LfcinB (15, 46). In the present study, we identified the protein targets of Bac7, P-Der, and PR-39, and analyzed the specific and common target proteins of the four AMPs through a bioinformatics analysis. KEGG analysis of specific protein targets of each AMP showed that the Bac7 and LfcinB combination targeted the purine metabolism; in addition, the LfcinB and PR-39 combination showed the same enrichment in LPS biosynthesis. If the combination of multiple antimicrobial treatments targeted proteins with same function (redundant proteins) or pathways with same function (related pathways), then an extensive synergistic effect would be observed because both the main and alternative proteins or pathways would be inhibited. This suggests that the combination of different AMPs targeting the same pathway might enhance the inhibitory ability of this pathway. Our antimicrobial assay validated our prediction. Previously, trial-and-error experiments have been conducted to explore the possible synergistic combinations; such experiments are labor intensive and time consuming. Our study shows that target analysis by using proteome chips is a powerful tool for predicting synergistic combinations. Furthermore, by analyzing AMP targets, we not only predicted synergistic combinations, but also identified previously unknown synergistic mechanisms of known combinations.

In future, we will analyze the synergistic mechanisms of known synergistic antimicrobial agent combinations by using proteome microarrays. The understanding of synergistic mechanisms will facilitate developing practicable antimicrobial strategies and thereby reduce antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank National Bio-Resource Project Japan for providing the ASKA E. coli ORF library.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.C. designed research; Y.H., P.S., and Y.C. performed research; Y.H., P.S., Y.C., and C.C. analyzed data; Y.H., P.S., and C.C. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology grants (NSC 101-2320-B-008-004-MY3, MOST 103-2627-M-008-001, and MOST 104-2320-B-008-002-MY3); the Aim for the Top University Project, National Central University, and Landseed Hospital Joint Research Program grant (NCU-LSH-103-A-001); and National Central University and Cathay General Hospital Join Research Program grants (102NCU-CGH-07, 103CGH-NCU-A3 and 104CGH-NCU-A1).

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- AMPs

- Antimicrobial peptides

- Bac 7

- Bactenecin 7

- Lfcin B

- Lactoferricin B

- P-Der

- Hybrid of pleurocidin and dermaseptin

- PR-39

- Proline-arginine-rice peptide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zasloff M. (2002) Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415, 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nicolas P. (2009) Multifunctional host defense peptides: intracellular-targeting antimicrobial peptides. FEBS J 276, 6483–6496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsu C. H., Chen C., Jou M. L., Lee A. Y., Lin Y. C., Yu Y. P., Huang W. T., and Wu S. H. (2005) Structural and DNA-binding studies on the bovine antimicrobial peptide, indolicidin: evidence for multiple conformations involved in binding to membranes and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 4053–4064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park C. B., Kim H. S., and Kim S. C. (1998) Mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide buforin II: buforin II kills microorganisms by penetrating the cell membrane and inhibiting cellular functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 244, 253–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brotz H., Bierbaum G., Leopold K., Reynolds P. E., and Sahl H. G. (1998) The lantibiotic mersacidin inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by targeting lipid II. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 154–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yonezawa A., Kuwahara J., Fujii N., and Sugiura Y. (1992) Binding of tachyplesin I to DNA revealed by footprinting analysis: significant contribution of secondary structure to DNA binding and implication for biological action. Biochemistry 31, 2998–3004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parks W. M., Bottrill A. R., Pierrat O. A., Durrant M. C., and Maxwell A. (2007) The action of the bacterial toxin, microcin B17, on DNA gyrase. Biochimie 89, 500–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heddle J. G., Blance S. J., Zamble D. B., Hollfelder F., Miller D. A., Wentzell L. M., Walsh C. T., and Maxwell A. (2001) The antibiotic microcin B17 is a DNA gyrase poison: characterisation of the mode of inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 1223–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mukhopadhyay J., Sineva E., Knight J., Levy R. M., and Ebright R. H. (2004) Antibacterial peptide microcin J25 inhibits transcription by binding within and obstructing the RNA polymerase secondary channel. Mol Cell 14, 739–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kragol G., Lovas S., Varadi G., Condie B. A., Hoffmann R., and Otvos L. Jr. (2001) The antibacterial peptide pyrrhocoricin inhibits the ATPase actions of DnaK and prevents chaperone-assisted protein folding. Biochemistry 40, 3016–3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Podda E., Benincasa M., Pacor S., Micali F., Mattiuzzo M., Gennaro R., and Scocchi M. (2006) Dual mode of action of Bac7, a proline-rich antibacterial peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760, 1732–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boman H. G., Agerberth B., and Boman A. (1993) Mechanisms of action on Escherichia coli of cecropin P1 and PR-39, two antibacterial peptides from pig intestine. Infect. Immun. 61, 2978–2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patrzykat A., Friedrich C. L., Zhang L., Mendoza V., and Hancock R. E. (2002) Sublethal concentrations of pleurocidin-derived antimicrobial peptides inhibit macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 605–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen C. S., Korobkova E., Chen H., Zhu J., Jian X., Tao S. C., He C., and Zhu H. (2008) A proteome chip approach reveals new DNA damage recognition activities in Escherichia coli. Na.t Methods 5, 69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ho Y. H., Sung T. C., and Chen C. S. (2012) Lactoferricin B inhibits the phosphorylation of the two-component system response regulators BasR and CreB. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, M111.014720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tu Y. H., Ho Y. H., Chuang Y. C., Chen P. C., and Chen C. S. (2011) Identification of lactoferricin B intracellular targets using an Escherichia coli proteome chip. PLoS ONE 6, e28197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen C. S., Sullivan S., Anderson T., Tan A. C., Alex P. J., Brant S. R., Cuffari C., Bayless T. M., Talor M. V., Burek C. L., Wang H., Li R., Datta L. W., Wu Y., Winslow R. L., Zhu H., and Li X. (2009) Identification of novel serological biomarkers for inflammatory bowel disease using Escherichia coli proteome chip. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 1765–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitagawa M., Ara T., Arifuzzaman M., Ioka-Nakamichi T., Inamoto E., Toyonaga H., and Mori H. (2005) Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 12, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu X., Gerstein M., and Snyder M. (2006) ProCAT: a data analysis approach for protein microarrays. Genome Biol. 7, R110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Natale D. A., Shankavaram U. T., Galperin M. Y., Wolf Y. I., Aravind L., and Koonin E. V. (2000) Towards understanding the first genome sequence of a crenarchaeon by genome annotation using clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (COGs). Genome Biol. 1, RESEARCH0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blake J. A., and Harris M. A. (2002) The Gene Ontology (GO) project: structured vocabularies for molecular biology and their application to genome and expression analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 7, Unit 72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanehisa M., Goto S., Sato Y., Furumichi M., and Tanabe M. (2012) KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., Pang N., Forslund K., Ceric G., Clements J., Heger A., Holm L., Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Bateman A., and Finn R. D. (2012) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hegreness M., Shoresh N., Damian D., Hartl D., and Kishony R. (2008) Accelerated evolution of resistance in multidrug environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13977–13981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iyer R., Williams C., and Miller C. (2003) Arginine-agmatine antiporter in extreme acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6556–6561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gong S., Richard H., and Foster J. W. (2003) YjdE (AdiC) is the arginine:agmatine antiporter essential for arginine-dependent acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185, 4402–4409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mardirossian M., Grzela R., Giglione C., Meinnel T., Gennaro R., Mergaert P., and Scocchi M. (2014) The host antimicrobial peptide Bac71–35 binds to bacterial ribosomal proteins and inhibits protein synthesis. Chem. Biol. 21, 1639–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scocchi M., Lüthy C., Decarli P., Mignogna G., Christen P., and Gennaro R. (2009) The proline-rich antibacterial peptide Bac7 binds to and inhibits in vitro the molecular chaperone DnaK. Int. J. Peptide Res.Therapeutics 15, 147–155 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yethon J. A., and Whitfield C. (2001) Lipopolysaccharide as a target for the development of novel therapeutics in gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 1, 91–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raetz C. R., Reynolds C. M., Trent M. S., and Bishop R. E. (2007) Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 295–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bermingham A., and Derrick J. P. (2002) The folic acid biosynthesis pathway in bacteria: evaluation of potential for antibacterial drug discovery. Bioessays 24, 637–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Levy C., Minnis D., and Derrick J. P. (2008) Dihydropteroate synthase from Streptococcus pneumoniae: structure, ligand recognition and mechanism of sulfonamide resistance. Biochem. J. 412, 379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhabha G., Tuttle L., Martinez-Yamout M. A., and Wright P. E. (2011) Identification of endogenous ligands bound to bacterially expressed human and E. coli dihydrofolate reductase by 2D NMR. FEBS Lett. 585, 3528–3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schnell J. R., Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2004) Structure, dynamics, and catalytic function of dihydrofolate reductase. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33, 119–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benkovic S. J., Fierke C. A., and Naylor A. M. (1988) Insights into enzyme function from studies on mutants of dihydrofolate reductase. Science 239, 1105–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Penner M. H., and Frieden C. (1987) Kinetic analysis of the mechanism of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 15908–15914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Durr U. H., Sudheendra U. S., and Ramamoorthy A. (2006) LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1408–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viola R. E. (2001) The central enzymes of the aspartate family of amino acid biosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 34, 339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Viola R. E., Faehnle C. R., Blanco J., Moore R. A., Liu X., Arachea B. T., and Pavlovsky A. G. (2011) The catalytic machinery of a key enzyme in amino Acid biosynthesis. J Amino Acids 352538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ulvatne H., Samuelsen O., Haukland H. H., Kramer M., and Vorland L. H. (2004) Lactoferricin B inhibits bacterial macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237, 377–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Audia J. P., Webb C. C., and Foster J. W. (2001) Breaking through the acid barrier: an orchestrated response to proton stress by enteric bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Castanie-Cornet M. P., Penfound T. A., Smith D., Elliott J. F., and Foster J. W. (1999) Control of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3525–3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Diez-Gonzalez F., and Karaibrahimoglu Y. (2004) Comparison of the glutamate-, arginine- and lysine-dependent acid resistance systems in Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96, 1237–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haukland H. H., Ulvatne H., Sandvik K., and Vorland L. H. (2001) The antimicrobial peptides lactoferricin B and magainin 2 cross over the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and reside in the cytoplasm. FEBS Lett. 508, 389–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park S. C., Park Y., and Hahm K. S. (2011) The Role of Antimicrobial Peptides in Preventing Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections and Biofilm Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 5971–5992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hu C. J., Song G., Huang W., Liu G. Z., Deng C. W., Zeng H. P., Wang L., Zhang F. C., Zhang X., Jeong J. S., Blackshaw S., Jiang L. Z., Zhu H., Wu L., and Li Y. Z. (2012) Identification of new autoantigens for primary biliary cirrhosis using human proteome microarrays. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 669–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.